The three pillars of American republicanism“Bill of Rights Socialism” was first put forward by Gus Hall, Chairman of the Communist Party, USA, in his 1990 pamphlet The American Way to Bill of Rights Socialism. Emile Shaw wrote in 1996 that Bill of Rights Socialism “conveys the idea that we will incorporate U.S. traditions into the structure of socialism that the working class will create.” Since then, the CPUSA has continued to deepen and expand this theory to correspond with the real needs of struggle. The CPUSA is not alone in this project; other communist parties have also been applying Marxism-Leninism creatively to produce important innovations, bringing socialist construction into the modern age while also adapting their own path to their unique national conditions. How could it be otherwise? All struggles for socialism have unfolded within the context of their particular national circumstances. In Vietnam, it produced “Ho Chi Minh Thought.” In Cuba, the revolution linked itself to the legacy of Jose Martí. The many innovations in China are known as “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” No struggle has ever discounted their unique political traditions and general national conditions and been successful in achieving liberation. US republican traditions were deeply influenced by the Roman republic, where political sovereignty was derived from a free citizenry rather than a single monarch. According to Irish philosopher and world-renowned political theorist Philip Pettit, this centuries-old tradition of republicanism can be defined by “three core ideas” familiar to any US citizen: The first idea, unsurprisingly, is that the equal freedom of its citizens, in particular their freedom as non-domination — the freedom that goes with not having to live under the potentially harmful power of another — is the primary concern of the state or republic. The second is that if the republic is to secure the freedom of its citizens then it must satisfy a range of constitutional constraints associated broadly with the mixed constitution. And the third idea is that if the citizens are to keep the republic to its proper business then they had better have the collective and individual virtue to track and contest public policies and initiatives: the price of liberty, in the old republican adage, is eternal vigilance.1 These “three core ideas” form the bedrock of the political tradition of the U.S. republic. Bill of Rights Socialism, then, must grapple with these three core ideas if we are to synthesize the revolutionary struggle of the working class with the unique political conditions of the United States. Freedom and the republic The ideological core of the U.S. is its emphasis on the concept of “freedom.” Anyone with even a passing familiarity of U.S. politics knows that every single other question revolves around this core ideal. No other single concept, even that of democracy, holds as much power as this idea. Pettit distinguishes two approaches to freedom: liberalism and republicanism, both of which were present at the birth of the United States. Liberalism developed out of the European enlightenment period. It was a product of the rising bourgeoisie, which sought to guarantee freedom of commerce while leaving many other areas of domination untouched. Its basis is the freedom of the individual to own and dispose of property with a minimum of state interference. Republican freedom is rooted in the Roman idea that to be free, a person must not suffer dominatio. This means that a free person must be free not only of active interference of political power but also inactive, latent interference by any outside force. Freedom is not only an act, but a status. The real enemy of freedom in the republican tradition is not just interference by political authorities; it is the arbitrary power that some people may have over others.2 Pettit elaborates: “[Freedom] means that you must not be exposed to a power of interference on the part of any others, even if they happen to like you and do not exercise that power against you.”3 Specifically, this means you are not free if you have a good boss or a good landlord who has the power to arbitrarily intervene against your employment or housing, but simply chooses not to do so. If that power exists, even in a latent and unexercised way, working-class people cannot be understood to have the status of freedom, since this “freedom” may arbitrarily change at any given moment. Working people under capitalism live in day-to-day dependence on the employing class. Pettit articulates what he refers to as the “eyeball test” to help clarify what republican freedom means: [Citizens] can look others in the eye without reason for the fear or deference that a power of interference might inspire; they can walk tall and assume the public status, objective and subjective, of being equal in this regard with the best. . . . The satisfaction of the test would mean for each person that others were unable, in the received phrase, to interfere at will and with impunity in their affairs.4 This definition of freedom should be intuitively familiar to all working-class people. Are you free if you have to pretend to be friends with your boss, bite your tongue, or fake your laughter to stay on the boss’s good side? When at-will employment prevails in so many workplaces, can working-class people be free if they can be fired for any reason or no reason at all? According to the republican definition of freedom, the answer is unequivocal: Working people are not free under capitalism. Crucially, this means republicanism is distinct from the libertarian theory of freedom. Rather than being concerned exclusively with a vertical theory of freedom, where the state alone is seen as a threat to freedom, republicanism is also concerned with the arbitrary power private citizens can have over one another. Republican freedom means freedom not only from arbitrary state interference, but also from abusive partners, racial and national discrimination, and the private tyrannies of modern capitalism. Republican freedom has always meant more than just free markets. Bill of Rights Socialism, then, recognizes the inherent contradiction of “freedom” in monopoly capitalism — it is a smokescreen for the objective increase of unfreedom for the sake of profit. In today’s stage of capitalist development, the objective condition of most of U.S. society and the broader world is to be unfree and dominated by finance monopoly capitalism and imperialism. Second, Bill of Rights Socialism asserts that this contradiction can be resolved only by putting an end to the dictatorship of monopoly capital through a popular, democratic revolution that elevates the working class to the leading, decisive social element constituting state power. The mixed constitution as a class balancing act The second “core idea” of republicanism is the “range of constitutional constraints associated broadly with the mixed constitution.” This tradition of the “mixed constitution” (mixed government) developed out of revolutionary class struggle as a way to balance the contradiction between the general “human” struggle for emancipation and the particular class project upon which the new state must be founded. The most well-known republic in ancient history was formed in Rome with the overthrow of the Roman monarch Lucius Tarquinius Superbus by the patrician aristocracy of Rome. Tarquinius’ rule had become so intolerable to the aristocracy that they resolved by degrees to overthrow him. Yet the patricians by themselves could not bring to bear enough force to decisively win in their revolutionary struggle. The revolution was sparked when the masses of plebians rioted over the rape of Lucretius by Tarquinius’ son and her subsequent suicide. This mass activity was critical for the aristocracy to unite and banish the monarchy and replace it with two consuls who would be able to “check” one another through a veto. The mixed constitutions of republics emerged out of this historical process as the institutionalization of a balanced form of class rule. The Roman aristocracy was able to secure its position of power in the Roman Senate. Yet spontaneous plebian activity in the revolutionary struggle forced the patricians to integrate the popular class into its republican system as well. Checks and balances in a republic are reflections of the underlying balance of class forces at a particular moment when that republic is first constituted. Machiavelli makes this observation explicitly in his Discourses on Livy: I say that those who condemn the dissensions between the nobility and the people seem to me to be finding fault with what as a first course kept Rome free, and to be considering quarrels and the noise that resulted from these dissensions rather than the good effects they brought about, they are not considering that in every republic there are two opposed factions, that of the people and that of the rich, and that all laws made in favor of liberty result from their discord.5 According to political scientist Kent Brudney, Machiavelli “accepted the class basis of political life and believed that class conflict could be beneficial to a republic.” The “creative possibilities of class conflict” were recognized for “their importance to the maintenance of Roman liberty.” Brudney continues: “The episodes of conflict between the Roman patriciate and the Roman people were vital to the development of good laws and to the continuity of Rome’s founding principles.”6 This class-struggle understanding of mixed constitutionalism was also at the fore in the debates around the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Scholar James Wallner directly connects the debates around the creation of the Senate with Machiavelli’s theory of institutionalized class struggle: The U.S. Senate exists for one overriding reason: to check the popularly elected U.S. House of Representatives. Throughout the summer of 1787, James Madison and his fellow delegates to the Federal Convention highlight, again and again, the Machiavellian observation that institutionalized conflict was essential to the preservation of the republic. Trying to inject an updated understanding of Machiavelli’s dictum into the heart of the new federal government, they created a Senate whose institutional features — size, membership-selection process, nature of representation, length of term of office, compensation — are properly understood only in relation to the body’s House checking role.7 Wallner points to Federalist Paper No. 62, where James Madison wrote: “The necessity of a senate is not less indicated by the propensity of all single and numerous assemblies to yield to the impulse of sudden and violent passions, and to be seduced by factious leaders into intemperate and pernicious resolutions.” The recent Shay’s Rebellion had been sparked by Massachusetts farmers demanding debt relief that was opposed by the merchant class that dominated the state government. This rebellion pressed the Federalist framers to consider the inclusion of an “aristocratic” senate capable of effectively subduing the “violent passions” of the masses, something missing from the Articles of Confederation that had preceded it.8 Thus, we see that “mixed constitutions” of republics are only the institutionalization of class struggle. If the republic is supposed to make the affairs of public power a question of public input, it must always balance the class foundation of the state with at least the nominal political participation of the masses. Ruling class power in a republic is always concentrated in the senate, and popular power is always located in a “lower” branch of government. This balance creates a dynamism between the two while also developing a hegemonic understanding of the state as representing “the whole people,” even if the state is always constituted under a specific class basis. Bill of Rights Socialism deepens the theory of the mixed constitution and gives it a proletarian character. Rather than calling for the abolition of the senate as such, Bill of Rights Socialism recognizes the need to reconstitute the republic along proletarian class lines, transforming the current senate founded on the “wisdom” of slave owners and oligarchs into an “industrial” senate that is instead based on the wisdom and experience of the leaders of the working class. Like Lenin’s soviets, the industrial senate would be built out of “the direct organisation of the working and exploited people themselves, which helps them to organise and administer their own state in every possible way.” Leaders, drawn from the broad working-class majority, would carry with them both an intimate knowledge of all parts of the production process and a distinct working-class perspective into the development of public policy. And like both the soviets and senates past, the industrial senate would be insulated from universal direct election, with a focus on cultivating tested working-class leadership collaborating to build and protect a common vision of a democratic socialist republic. The class character of the senate would serve as a “check” on one side of the equation.9 But Bill of Rights Socialism can grow only out of the success of a massive people’s front. Led by the organized working class, this front would also contain all progressive people and class allies, including small farmers, small- and medium-size-business owners, the self-employed, and independent intellectuals and professionals. The primary stage of socialism does not end class struggle but transforms it under the decisive political rule of the working class. A “People’s House” would provide a democratic space for these other class elements to make constructive and progressive contributions to building socialism without sacrificing or obscuring the working-class nature of the new republic. Further, experience from the last century indicates that even a working-class state can degenerate bureaucratically without broader popular participation and oversight. In addition to incorporating non-proletarian class elements constructively into the workers’ republic, the lower house would also provide a space for the exercise of universal suffrage and the direct election of representatives by the whole people. These popular representatives could play a consultative role to the industrial senate and provide institutional oversight. This would provide a “check” on the other side of the equation. The “checks and balances” between the industrial senate and the people’s house would capture the “quarrels and the noise” familiar to American democracy while preserving absolutely the republic’s fundamental class nature. This dynamic interrelationship creates the conditions for the third core idea of republicanism to prevail, the “contestatory citizenry.” It is right to rebel (within limits) The third core idea of republicanism depends on the active engagement of its citizens “to track and contest public policies and initiatives.” Freedom can be secured only through struggle. This ideal has been a fundamental political principle of all oppressed people struggling for their democratic rights and freedom in the United States. Frederick Douglass taught us years ago the price of freedom: If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.10 The contestatory citizenry forms a fundamental basis for the Bill of Rights and so must serve as a basis for Bill of Rights Socialism. These rights include freedom of speech, of assembly, of faith and conscience, and the right to be informed about the functioning of public power. Politically critical art, protests, and organizations must play a fundamental role in the construction of socialism in the United States and thus must be protected under Bill of Rights Socialism. Struggle does not only occur between oppressor and oppressed, between exploiter and exploited. Struggle also goes on within the oppressed and exploited. Historical development has created an unevenness within the working class: divisions around race, sex, sexuality, religion, cultural beliefs, nationality, language, and so on. This unevenness can be overcome only after a long period of struggle to resolve these divisions and build a unity through our diversity; to give real content to the national motto “E Pluribus Unum.” While the initial steps in this process of internal struggle for unity within the working class and democratic forces must be made before the establishment of socialism by building a people’s front, the establishment of socialism does not mechanically erase the social unevenness within that people’s front overnight. Revolution and reform are distinct, but also deeply interrelated. The development of social scientific methods and professional specialization has produced the historical capacity to carry out deep and broad reforms to the social system in a planned, scientific, and rational way. Reform can and must always go on, improving social institutions and making sure they advance with the times. However, reform does not happen abstractly, but according to the degree of political will brought to bear on the process. Reform in a social system hits a wall when the ruling class is no longer willing to exercise its political will to allow the reform process to deepen and expand according to the needs of the populace. Revolution is not in and of itself the solution to social problems; revolution is the punctuated transformation from one form of class rule to the next. This transformation in class rule does not replace reform, but unlocks it to unfold more deeply, at a faster pace, and in a more thoroughgoing way than the degenerate ruling class that was replaced could or would allow. By elevating the working class to the level of the ruling class in a workers’ republic, the struggle for reforms is not ended but transformed. Republicanism allows this reform struggle to take place both on an individual, contestatory foundation protected by a socialist Bill of Rights, as well as within the bounds of law constrained by socialist constitutional forms. Peace, prosperity, democracy, and freedomLet us be crystal clear: the United States needs a socialist revolution. The old ruling class, dominated by finance monopoly capital and incapable of keeping pace with the needs of the time, must be overthrown and in its place the working class, at the head of a mass democratic movement of all oppressed people and classes, must be elevated to rule in its place. The class basis of the current republic must not be ignored but instead placed at the center of the conversation. But the struggle is not to “abolish” the republican form outright. There are no serious ideas, to be perfectly frank, on what to put in its place. The soviet system was for the Soviets, the Chinese system for the Chinese, so on. The struggle is to revolutionize the republic to preserve the republican system at a higher level of development. Indeed, the fundamental argument of Bill of Rights Socialism must be that only a socialist revolution can preserve the republican liberties and democratic rights that so many oppressed and exploited people have fought hard and made tremendous sacrifices to secure. Socialist revolution means the deepening of democracy under the decisive state leadership of the working class. This essay is only a theoretical sketch to show the consistency between Marxism-Leninism and the “core ideas” of the republican political tradition. There are an almost limitless number of questions that arise from its premise: Can a workers’ republic be secured through the amendment process or through a new Constitutional Convention? How exactly should an industrial senate be ordered and secured? Should it be through indirect election, sortition (selection by lottery), selection, or a combination? How does federalism fit into this picture? How can we more explicitly articulate its relationship to imperialism and oppressed nations? And many more. Only through thoughtful struggle — not isolated contemplation or outrageous sloganeering — can the political soil be tilled to allow new possibilities to develop. Bill of Rights Socialism is not an “answer” in itself but a path to be blazed by combining the creative leadership of the Communist Party with the limitless dynamism and transformative potential of millions of Americans from all backgrounds linked together in the struggle for peace, prosperity, democracy, and republican freedom. Sources

AuthorBradley Crowder was born and raised in the Permian Basin oil patch that spans eastern New Mexico and west Texas. He is a labor organizer that has worked with the American Federation of Teachers and the Fight For 15. He has his undergraduate in economics from Texas State University and currently working on his master's degree in labor studies at UMass - Amherst. He is a proud member of the Communist Party, USA. Republished from CPUSA

7 Comments

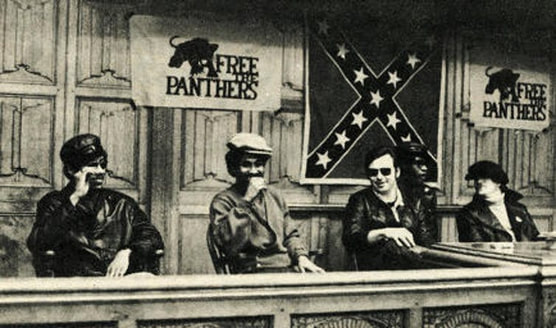

It is generally accepted by most on the ‘left’ that capitalism required the black slave for capital to be “kick-started”,[1] and consequently, that the similarities in the lives of the early black slave and the white indentured servant required the creation of racial differentiation (hierarchical and racist in nature) to prevent Bacon’s Rebellion style class solidarity across racial lines from reoccurring. The capitalist class in the US has been historically successful in creating an atmosphere within the circles of radical labor that excludes solidarity with black liberation and feminist struggles. Yet, the black community historically has been at the forefront of the struggle for socialism in the US. Taking into consideration the history of dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, radical labor in the US has had towards black struggles for liberation, how could it be that the black community has stood in a vanguard position in the struggle for an emancipation that would include those whom they have been excluded by? This paper will look at two occasions in which we can see the exclusion of identity struggles from labor struggles, and answer the riddle of how white labor has been able to identify more with capitalist of their own race than with their fellow nonwhite worker. In connection to this, we will be examining three different perspectives concerning the relationship of the black community’s receptivity and active role in the struggle for socialism and the emancipation of labor. A perfect example of this previously mentioned exclusion of identity from labor can be seen in Jacksonian radical democrats like Orestes Brownson, who although representing a radical emancipatory thought in relation to labor, failed to see how the abolitionist movement should have been included into the cause of the northern workers. Thus, his positions was (before falling into conservatism), that “we can legitimate our own right to freedom only by arguments which prove also the negro’s right to be free”.[2] The question is the negro’s right to be free when? Although he included blacks into the general emancipatory process, he was staunchly against abolitionist as “impractical and out of step with the times”,[3] and eventually urged northern labor to side with the southern plantation owners to counter the force of the northern industrial capitalist. What we see here with Brownson is a dismissal for the abolitionist struggle against black chattel slavery, unless it takes a secondary role to white labor’s struggle for the abolition of wage slavery. Brownson’s central flaw here is his assumption that you can free one while maintaining the other in chains, whereas the reality is that “labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded”[4] In the generation of American radicals that came after Brownson we see a similar dynamic between the 48’ers[5] of the first section of the International and the utopian/feminist radicals of sections nine and twelve. This split takes place between Sorge and the German Marxist and the followers of the ‘radical’ Stephen Andrews and the spiritualist free-love feminist Victoria Woodhull. As Herreshoff states, in relation to the feminist movement of the time, “the Marxists were talking to the feminist the way Brownson had talked to the abolitionist before the Civil War.”[6] By this what is meant is that the struggle for women’s political emancipation, was treated as a sideline issue, that should be dealt with – or automatically solved – only after labor’s emancipation. Now, it could very well be argued that the positions taken by Sorge and some of the other Marxist 48’ers was not ‘Marxist’ at all. Marx and Engels were staunch abolitionist, close followers (and writers) of the Civil War, and even pressured Lincoln greatly towards taking up the cause of emancipation; this puts them in a direct opposition to the positions taken by the northern labor radicals like Brownson[7]. Engels also pronounced himself fully in favor of women’s suffrage as essential in the struggle for socialism[8]. The expansion of this argument cannot be taken up here though. The point is that racial and sexual contradictions within the working masses have played an essential function in maintaining the capitalist structures of power. While workers identify – or are coerced into identifying – workers of other races, ethnicities, or sexes as their enemy, their real enemy – their boss – is either ignored or positively identified with. Thus, white workers can blame their wage cuts/stagnations on the undocumented immigrant. Although he does play a function in maintaining wages low, the one who sets the terms for the function the immigrant is coerced into playing is the capitalist, not the immigrant. There are countless analogies to describe this relation, my favorite perhaps is the one of the cookies. In a table you have 100 cookies, on one side of the table you have the capitalist (usually caricatured as a heavy-set fellow) with 99 cookies to eat for himself. On the other side you have a dirtied white face worker, a dirtied brown face immigrant worker, and finally, the last cookie. The capitalist leans to the white worker and tells him, “be careful, the immigrant will take your cookie”. Here we have the general function of racial division, the motto which is “have the white worker base his identification not in the dirt on his face, but in the mythical face laying under the dirt”. This mythical face under the dirt is the symbolic link of the white worker and the white capitalist. The link of commonality is based on the illusion of the undirtied faced white worker. The dirt, of course, symbolizes the everyday conditions of his toiling existence. Even though the white worker’s everydayness is infinitely more like the immigrant’s (immigrant here is replaceable with black/women/etc.), he is coerced into consenting his identification with whom he has in common no more than one does with a bloodsucking mosquito on a hot summer’s day. Regardless of the dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, of radical labor’s relation to other identity struggles, the black community has been in the forefront of the struggle for socialism in America. Not only have elements of the black community consistently served as the revolutionary vanguard, but the community itself has historically expressed a receptivity of socialism that is unmatched by their white working-class counterparts. There have been a few interesting ways of explaining the phenomenon of the black community’s receptivity of socialist ideas. Edward Wilmont Blyden, sometimes called the father of Pan-Africanism, argued in his text African Life and Customs that the African community is historically communistic. Thus, there is something communistic within the ethos of the black community, that even though it has been generationally separated from its origins, maintains itself in the black experience. He states that the African community produced to satisfy the “needs of life”, held the “land and the water [as] accessible to all. Nobody is in want of either, for work, for food, or for clothing.” The African community had a “communistic or cooperative” social life, where “all work for each, and each work for all.”[9] The argument that a community’s spirit or ethos plays an essential role in its ability to be receptive to socialism is one that is also being analyzed with respect to the “primitive communism” of indigenous communities in South America. Most famously this is seen in Mariategui, who states: “In Indian villages where families are grouped together that have lost the bonds of their ancestral heritage and community work, hardy and stubborn habits of cooperation and solidarity still survive that are the empirical expression of a communist spirit. The “community” is the instrument of this spirit. When expropriations and redistribution seem about to liquidate the “community,” indigenous socialism always finds a way to reject, resist, or evade this incursion.”[10] These arguments have been recently found by Latin American Marxist scholars like Néstor Kohan, Álvaro Garcia Linera, and Enrique Dussel, to have already been present in Marx. From the readings of Marx’s annotations of the anthropological texts of his time (specifically Kovalevsky’s), they argue that Marx began to see the revolutionary potential of the “communards” in their communistic sprit. This was a spirit that staunchly rejected capitalist individualism, leading him to believe that its clash with the expansive nature of capital, if victorious, could be an even quicker path to socialism than a proletarian revolution. Not only would the indigenous community serve as an ally of the proletariat as revolutionary agent, but the communistic spirited community is itself a revolutionary agent too.[11][12] Another way of explaining the phenomenon of a historically white radical labor movement (at least until the founding of CPUSA in 1919), and a historically radical black community[13], is through reference to an interview Angela Davis does from prison when asked a similar question. In this 1972 interview Angela mentions that the black community does not have the “hang ups” the majority of the white community has when they hear the word ‘communism’. She goes on to describe an encounter with a black man who tells her that although he does not know what communism is, “there must be something good about it because otherwise the man wouldn’t be coming down on you so hard.”[14] What we have here is a sort of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. The acceptance of communism is because of the militant rejection my oppressor has towards it. Although it might seem as a ‘simplistic’ conclusion, I assure there is a profound rationality behind it. The rationality is this “if the alternative is not different enough to scare my oppressors shitless, it is not an alternative where my conditions as oppressed will change much.” This logic, simplistic as it might seem, is one the current ‘socialist’ movement in the US is in dire need of re-examining. If the alternatives one is proposing does not bring fright upon those whose heels your necks are under, then what one is proposing is no qualitative alternative at all; rather, it is merely a request to play within the parameters the ruling class gives you. The relationship of who is setting the parameters is not changed by the mere expansion of them. Both of these ways of examining the question concerning the relationship of the black community and its acceptance of socialist ideas I believe hold quite a bit of truth to them. Regardless, I think there is one more way to answer this question. The difference is that in this new way of answering the question, we are threatened with finding the possibility of the question itself being antiquated. The thesis I think is worth examining relates to this previous “mythical link” the white worker can establish with the white capitalist. Unlike the white worker, the black worker has not – at least historically – had the ability to identify with a black capitalist from the reflective position of his ‘undirtied’ face. This is given to the fact that the capitalist class, or even broader, the class of elites or the top 1%, has been almost homogeneously white. Thus, whereas the white worker could be manipulated into identifying with the white capitalist, the white homogeneity of the capitalist class did not have the ripe conditions for working class black folks to be manipulated in the same manner. The question we must ask ourselves now is: in a world of a socially ‘progressive’ bourgeois class, like the one we have today, can this ‘mythic-link’ come into a position of possibly becoming a possibility? With the efforts of racial (and sexual) diversification of the top 1%, can this change the relationship of the black community to radical politics? If we accept the thesis that the link of the black community to radical politics has been a result of not being able to – unlike the white worker – have any identity commonality with their exploiter, then, can we say that in a world of a diversified bourgeois class, the radical ethos of the black community is under threat? Is the black working mass and poor going to fall susceptible to the identity loophole capitalism creates for coercing workers into consenting against their own interest? Or will its historical radical ethos be able to challenge it, and see the black bourgeois as much of an enemy as the white bourgeois? Under a diversified bourgeois class, will Booker T. Washington style black capitalism become hegemonic in the black community? Or will the spirit still be that of Fred Hampton’s famous dictum from his Political Prisoner speech “You don’t fight fire with fire. You fight fire with water. We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity. We’re not gonna fight capitalism with black capitalism We’re gonna fight capitalism with socialism.”? I am unsure, but I think perhaps a totally disjunction-al way of thinking about it is incorrect; as in, the disjunction will not be one the totality of the community is forced to homogeneously choose, but one which fractures the community itself without leaving any side’s perspective hegemonized. Regardless, I think it is up to those who represent the cause of the white and non-white working mass and poor, to go these spaces and assure that masses begin to identify based on class lines (‘class’ not restrictive to the industrial proletariat, but expanded to the totality of the working masses, and beyond that to the lumpen elements whose systemic exclusion, excludes them as well from being exploited subjects of the system). Only in this ‘class’ identity approach can we achieve the unity necessary to solve not just the antagonisms of class that capitalism develops and continuously exacerbates, but also those of race, sex, and climate. This does not mean, like it meant for the 19th century labor radicals, that we exclude non-class struggles to a peripherical position where we give them importance only after the socialist revolution has triumphed. Rather, our commonality of interests in transcending the present society forces us to examine how we can work together, and in doing so, begin to acknowledge and work on the overcoming of our own contradictions with each other. Citations. [1]III, F. B. (2003). The Prison Slave as Hegemony's (Silent) Scandel. In Afro-Pessimism An Introduction (pp. 72). [2] Brownson, O. A. “Slavery-Abolitionism.” Boston Quarterly Review, I (1838), (pp. 240). [3] Herreshoff, D. American Disciples of Marx (Wayne State University Press, 1967), (pp. 39). [4] Marx, K. (1967). Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production (Vol. 1). (F. Engels, Ed.) International Publishers. (pp. 301) [5] “48’ers” refers to the Germans that came after the attempted revolution of 1848 (the one the Communist Manifesto was written for). Having to face persecution, many fled to the US. [6] Ibid. (pp. 82). [7] For more see: Marx, K. & Engels, F. The Civil War in the United States (International Publishers, 2016) [8] For more see: Engels, F. The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (International Publishers, 1975) [9] Blyden, E. W. African Life and Customs (Black Classic Press, 1994) (pp. 10-11) [10] Mariategui, J. C. Seven Essays of Interpretation of Peruvian Reality (1928), (pp. 68) [11] Linera, A. G. (2015) Cuaderno Kovalevsky. In Karl Marx: Escritos Sobre la Comunidad Ancestral [12] This is itself a message that strikes at the heart of the dogmatism of certain Marxist circles. Circles that religiously follow the early unilateral theory of history Marx’s begins proposing in The German Ideology, a view that was used to argue the revolutionary futility of these communities, and the need to ‘proletarianize’ them. This does not mean we throw out Marx’s discovery of the materialist theory of history upon which the unilateral theory of history arises; but rather, that we treat it in a truly materialist manner (as the later Marx does) and realize the ‘five steps’ to communism is materially specific to the studies Marx had done with relation to the European context. With relation to other contexts, new studies must be made through the same materialist methodology. [13] This is not to be taken as a statement of the homogenous radicalism of the black community in America. The influence of Booker T Washington style of black capitalist ideology does historically have a certain influence in the black community. But, when considered in proportion to the white population, the acceptance of socialism – and its vanguard role in struggles – has been much greater in the black community. [14] Marxist, Afro. (2017, June 11) Angela Davis - Why I am a Communist (1972 Interview) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGQCzP-dBvg About the Author:

My name is Carlos and I am a Cuban-American Marxist. I graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Loras College and am currently a graduate student and Teachers Assistant in Philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. My area of specialization is Marxist Philosophy. My current research interest is in the history of American radical thought, and examining how philosophy can play a revolutionary role . I also run the philosophy YouTube channel Tu Esquina Filosofica and organized for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Cooperatives, enterprises where workers are the owners of their workplace, have always held an awkward place in the socialist movement. Proponents, such as Robert Owen, saw worker cooperatives as socialism in practice. Other socialists, such as Karl Marx criticized cooperative projects for being “utopian” in the sense that cooperative advocates sought to build a socialist society without first dismantling the existing order. Rosa Luxemburg’s critique of the cooperative movement best exemplified the thought among many Marxists, “The workers forming a co-operative in the field of production are thus faced with the contradictory necessity of governing themselves with the utmost absolutism. They are obliged to take toward themselves the role of capitalist entrepreneur—a contradiction that accounts for the usual failure of production co-operatives which either become pure capitalist enterprises or, if the workers’ interests continue to predominate, end by dissolving.” Mark and Luxembourg were not wrong. Take the Mondragon Corporation, which is the largest worker cooperative in the world, employing 81,507 people and generating 12 billion euros in revenue. But market pressures to maximize profits over the broader interests of the community have eroded Mondragon to adopt exploitative practices typical of a corporation. Today, only a minority of Mondragon’s workers are owners and the cooperative is infamous for suppressing labor unions in its foreign subsidiaries. As cooperatives became more profitable, the worker-owners started to lose their sense of solidarity with their fellow workers as their self-image takes on the contours of a small business owner. Are cooperatives fated to end up like Mondragon? A growing group of organizers and academics are firmly saying “NO.” Learning from the accomplishments and failures by previous socialist experiments, these activists are confronting the assumptions that cooperatives cannot dismantle the existing institutions of oppression, are anti-political, and suppress class consciousness. But before that, let’s talk about the other and larger socialist movement that has dominated much of the 20th century. The Social Democratic CenturyMost leftists agreed with Luxembourg and instead opted to join the social democratic movement. Unlike cooperatives, social democracy was perceived as political and militant. Social democrats believed the best path to abolish capitalism was by expanding the state bureaucracy through political parties and trade unions. The legacy of the New Deal era, a period of high union density and massive expansion of government programs, seemed to have validated those beliefs. But what followed social democracy wasn’t socialism, what followed was neoliberalism, also known as a 40-year bipartisan effort to undo every aspect of the New Deal from slashing taxes for the rich, weaponizing racist dog whistles as an excuse to gut welfare, and pass massive layoffs in the industrial heartland. In their book “Bigger than Bernie”, Jacobin contributors Meagan Day and Micah Uetricht argue that the revived socialist movement’s main priority should be to finish the New Deal. Day and Uectricht’s call to undo the last 40 years is best reflected in the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) national platform, which currently consists of building a rank and file labor movement, electing democratic socialists to office, and passing Medicare for All and a Green New Deal. Though Day and Uetricht acknowledge it’s simply not enough to rebuild the welfare state. As numerous historians have pointed out, a major cause for the downfall of the social democratic era was union bureaucrat’s suppression of militant labor organizers during the 2nd Red Scare. Day and Uetricht advocate for a supposedly revised version they call “class struggle social democracy.” The basic idea is that socialists should elect social democratic politicians and agitate for a militant labor movement at the same time. The assumption is that a militant labor movement can act as a check on social democracy’s tendency “to limit the scope and substance of the reforms which it has itself proposed and implemented, in an endeavor to pacify and accommodate capitalist forces." But organizing a militant labor movement isn’t new, it was actually the main strategy for social democrats in the 20th century. While the CIO leadership did try to contain the more radical sections of the labor movement, the labor federation still relied on militant actions to force concessions. In 1936, the United Auto Workers organized the famous Flint Sitdown Strike, even though the Wagner Act already created the National Labor Relations Court to mediate labor disputes the year before. Union bureaucrats containing more militant activists can only explain part of the decline of social democracy, a greater factor was the expansion of the professional-managerial class. A large reason why so many working-class households left the union hall for the cubicle was the level of education and experience many white-collar jobs required allowed those workers to negotiate higher wages without the need for a union. A New York Times article on Tom Harkin’s failed 1992 presidential run sums up how devastating the professionalization of America had an effect on the left, "The audience for Harkin's message is literally and figuratively dying," says Mike McCurry, the senior communications adviser to Kerrey. "It's just not appealing to the baby boomers, the geodemographic bulge that accounted for the Republican ascendancy of the 80's and that might signal a new Democratic resurgence in the 90's. These are people with virtually no party affiliations. The imagery of Roosevelt's New Deal simply does not resonate with them." A revived social democratic movement will only recreate this cycle of a generous welfare state expanding a professional middle class that would push for reforms that will then shrink the middle class and so on and so forth. But can the cooperative, that utopian experiment, provide a new path towards socialism? Cooperative activists correctly point out that worker-ownership reverses the dynamics between management and labor and thereby provide a much more radical transformation than expanding government programs and trade union density. Three case studies, one historical and two that are ongoing, provide evidence that cooperatives do not inherently have to cave to market forces but can act as a catalyst for social movements, and most importantly, by allowing people to experience a life where workers can own the means of production, they can counter the pressures to assimilate back to capitalism. The Populist Movement

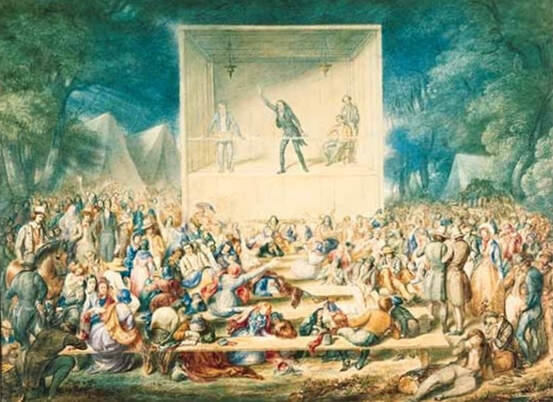

The Civil War violently abolished America’s slave economy, but the war did not abolish crippling poverty for poor whites and emancipated slaves. The Civil War had accelerated America's industrial revolution. Slavery was not replaced with the Jeffersonian ideal of every man their own entrepreneur, instead, slavery was replaced with a more modern form of capitalism, the crop-lien system. Merchants known as "the furnishing man" by white farmers and "the man" by black sharecroppers, controlled the post-war cotton industry. The furnishing men ensured that farmers were perpetually kept in poverty by forcing farmers to pay exorbitant interest rates and seizing their crops as collateral or lien. By taking crops as collateral, the furnishing man reaped the farmer’s surplus. In response to what amounted to debt slavery, cotton farmers in the South and later corn and wheat farmers in the Midwest, organized cooperatives through the National Farmers Alliance to fight back against the crop lien system. Unlike previous cooperative societies, the populists were both confrontational and class-conscious. The populists inaugurated what Lawrence Goodwyn called, "the largest democratic mass movement in American history." Similar to a labor union, a farmer’s cooperative was a collective of farmers that allowed them to bargain with merchants for livable prices. According to Goodwyn, America’s founding ideology of meritocracy and rugged individualism forced farmers to create an entirely separate political tradition rooted in class warfare. The Farmers Alliance accomplished this feat by instituting a circuit of traveling lecturers who sought to replace the Jeffersonian myth of the farmer as the entrepreneur with an ideology that placed farmers and wage workers as members of the “producing class” being exploited by the financial monopoly. The growing class consciousness among farmers drove the National Farmers Alliance to seek an alliance with the labor movement through the Knights of Labor. According to one anti-union newspaper, the aid that farmers were giving to the Knights of Labor was integral to the Great Southwest Strike, “but for the aid strikers are receiving from farmers alliances in the state and contributions outside, the Knights would have gone back to work long ago.” However intense opposition by the railroad monopolies prevented the cooperatives from replacing the furnishing men, so the populists entered the political scene. In 1892, farmers formed the People's Party, the most successful third party in American history. The People's Party elected 11 governors, 35 members of the house of representatives, and six senators. But tragically, the populist movement does not have a happy ending. The People’s Party collapsed after their endorsed presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, lost to monopoly backed candidate, William McKinley. Bryan was not the populist’s first pick, he had actually refused to endorse the party’s most important demand, a radical transition of America’s monetary system from the gold standard to fiat money, a transformation we would not see until the 1970s. The populists also failed to dismantle America’s racial and regional divides, preventing the farmers from forming a strong alliance with black sharecroppers and northern industrial workers who became disorganized after the Knights of Labor dissolved. Worst of all, even after nearly two decades of fighting, the merchant and railroad monopolies were still intact, which took a huge toll on farmers’ morale. However, the remnants of the populist movement would later form the backbone for the burgeoning Socialist Party. Cooperative Jackson'“Politics without economics is symbol without substance”. This old Black Nationalist adage summarizes and defines Cooperation Jackson’s relationship to the Jackson-Kush Plan and the political aims and objectives of the New Afrikan People’s Organization and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement in putting it forward.' In the heart of the deep south, Chockwe Antar Lumumba, the socialist mayor of Jackson, Mississippi is promising to build "the most radical city on the planet." Lumumba and his father, the former mayor, also named Chockwe Lumumba, have been part of a decades-long fight to fulfill the Jackson-Kush plan, an ambitious promise to transform Jackson into a solidarity economy, a network of worker cooperatives, urban farms, and community land trusts. What may be most unique about Jackson-Kush is that it’s not rooted in the populist era cooperative movement or English mutual societies. Instead, Jackson-Kush is based on the ideology of pan-Africanism. The elder Lumumba, a veteran of the black power movement, was inspired by former Tanzanian president Julius Nyere’s theory of Ujamaa and Fannie Lou Hamer's Freedom Farms. Activists in Jackson began the movement by organizing the "People's Assembly." Taking inspiration from previous experiments in post-Katrina New Orleans, the People’s Assembly was a mass forum for citizens to address community issues, wage strategic campaigns to leverage pressure on political and economic decision-makers, and foster a culture of direct democracy. The assembly was incredibly effective in its goals, reaching 300 members by 2010. The People’s Assemblies were more than just a mechanism for direct democracy, they were a cultural revolution. Most city governments are run like personal fiefdoms, preserved through a system of patronage and party machines. The Peoples’ Assembly flipped that model by agitating the largely black and working-class population to become active decision-makers. The elder Chockwe channeled the politicization from the People’s Assembly towards an electoral landslide in 2013, winning the mayorship with 80 percent of the vote. Tragically, the elder Lumumba died only seven months into office. In 2014, Lumumba's son founded Cooperation Jackson, a grassroots organization committed to building a solidarity economy, which also became the base for Chockwe Antar’s successful 2017 election. However, relations between the mayor and activists started to sour. Lumumba drained the People’s Assembly of most of their top organizers and staff, which created a rift between city hall and the grassroots. Lumumba’s actions were partly in response to Mississippi’s white supremacist state legislature maneuvering to take away Jackson’s local control, including engaging in a tense legal battle with the city government threatening to take over the Medgar Wiley Evers Airport. Cooperation Jackson, the organization Lumumba founded, has started to focus on building the Jackson-Kush plan independent of the state. Cooperation Jackson’s possible shift away from politics risks the project eroding into the same pressures as Mondragon. However, Chockwe Antar Lumumba still has a working relationship with grassroots activists and against all odds is still pushing through with his promise to turn Jackson-Kush from a dream into a reality. It is hard to tell what the future holds for Jackson, Mississippi, but one thing is clear, only through the state will there be a transition to the solidarity economy. Democracy Collaborative“We on the Left can once again set about our historic task of constructing in earnest the kind of possible future world in which we’d actually want to live.” At the turn of the 21st century, a group of academics and activists created Democracy Collaborative to answer the criticisms that market forces will inherently erode cooperatives into a typical capitalist enterprise. Democracy Collaborative can't really be given a single label, it's a think tank, a business incubator, and a grassroots lobbying arm all-in-one. Their answer to the market pressure argument is a program they call "community wealth building." Under this framework, cooperatives are only one part of a larger economic system. The local community, through the state and NGOs, invest in worker-owned cooperatives, which are guaranteed employment through contracts with something known as "anchor institutions," businesses that are not going to be leaving the community. Most importantly, the decision-makers are not limited to the existing worker-owners but include the government, community leaders, and in some cases labor unions. It is important to remember that power and status in Mondragon is not determined by stratified educational levels and bargaining power, but by membership into the cooperative. Under Mondragon's structure, a worker-owner on Fagor's assembly line is more privileged than a programmer who was only an employee. Mondragon's erosion back to capitalist norms was caused by worker-owners excluding the next generation of membership, mutating worker ownership from a form of economic democracy into an exclusive club. By expanding the decision-makers beyond the worker-owner, community wealth building creates a check on worker-owners potential greed. To prove the viability of their model, Democracy Collaborative decided to test their model in Cleveland, Ohio. Cleveland is a textbook example of deindustrialization. Decades of neoliberalism, offshoring of manufacturing jobs, and white supremacist policy has turned Cleveland into one of the poorest cities in America. In 2010, the city government and several NGOs created the "Evergreen Cooperatives," which are three worker-owned cooperatives: Laundry, Energy Solutions, and Green City Growers. The Evergreen Cooperatives were deliberately set up in neighborhoods with a median income of $18,500, a disproportionately large undereducated workforce, and an unemployment rate of 25 percent. Evergreen also explicitly hired workers with prior felony charges. The cooperatives were guaranteed a contract with local anchor institutions, such as the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals. Like any new business, there were some early mistakes. The cooperatives had an overambitious target of 1000 employees and the lack of financial literacy among workers forced the cooperative to adopt a more representative model of governance. However, within a decade, Evergreen has grown to more than 100 workers, 30% of whom are already worker-owners. Two out of three of the cooperatives are profitable, with Green City Growers on track to profitability. Currently, only 15% of the revenue comes from the original anchor institutions. Keep in mind, this is all inside one of the poorest and under-invested-in cities in America. Through Community Wealth Building, Democracy Collaborative reversed the neoliberal norm of cities begging for corporate contracts by cutting public services. But Democracy Collaborative was never satisfied with merely proving there is an alternative to the status quo. During a Q and A session at Cornell College, Thomas Hanna elaborated that Evergreen is only a proof of concept, the main vision is to directly transition existing businesses and industries, from Amazon to Wall Street. Democracy Collaborative has intensely lobbied politicians, political parties, and organizers towards this program. Already the Bernie Sanders 2020 presidential campaign, the UK Labour Party, and People's Action, a million-member community organizing network, have all adopted the community wealth building framework. Community wealth building should not be seen as a “startup incubator”, but a spiritual successor to Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs vision for "the whole of all industry to represent a giant corporation in which all citizens are shareholders and the state will represent the board of directors acting for the whole people." ConclusionWhat the three case studies have shown us is that the answer to Luxembourg’s criticisms is not to abandon the cooperative, the answer is to integrate cooperatives into militant social movements. Each case study has directly challenged the existing order, actively engaged in the political sphere, and created an alternative analysis of the dominant narrative. The populists built agrarian cooperatives to organize a militant social movement and politicize farmers. Cooperation Jackson’s plan for a solidarity economy became the basis for a successful political campaign and created a radical vision of black self-determination. Democracy Collaborative proved that cooperatives do not have to succumb to market forces. More importantly, the three case studies are causing many leftists to question if the distinction between cooperative projects and social democracy still matters. Nationalizing key industries does not inherently contradict the cooperative’s effort to expand workplace and economic democracy, if anything they complement each other. Thomas Hanna recently published “Our Commonwealth,” where he argues for expanding public ownership through publicly owned enterprises in red states, such as the North Dakota Public Bank. Bernie Sanders' 2020 labor platform included a promise to force large corporations to divert 20 percent of their stock to an ownership fund democratically controlled by workers, itself influenced by the Meidner plan, a policy proposed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party in the 1970s. The Marxist economist, Richard Wolff, maybe right when he called cooperatives “Socialism in the 21st century.” About the Author: