|

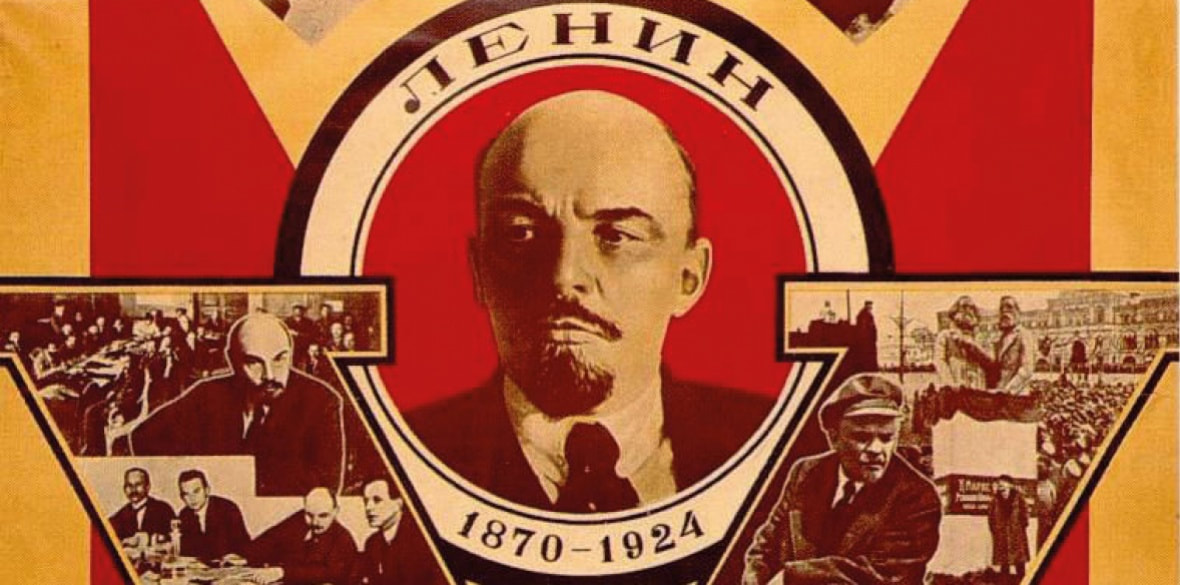

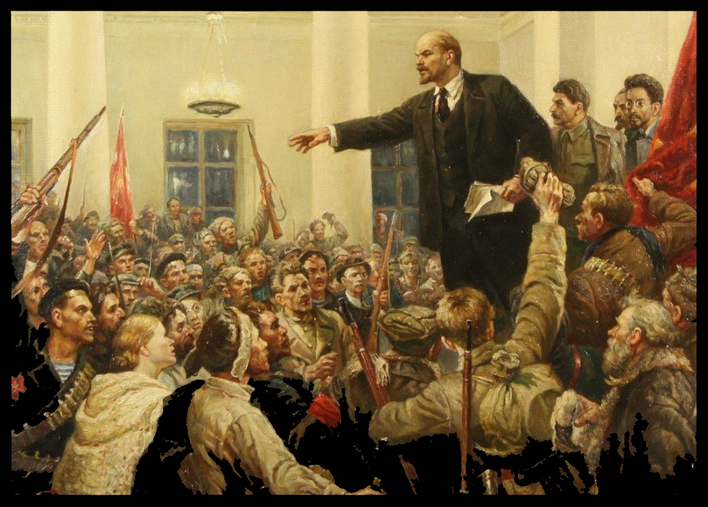

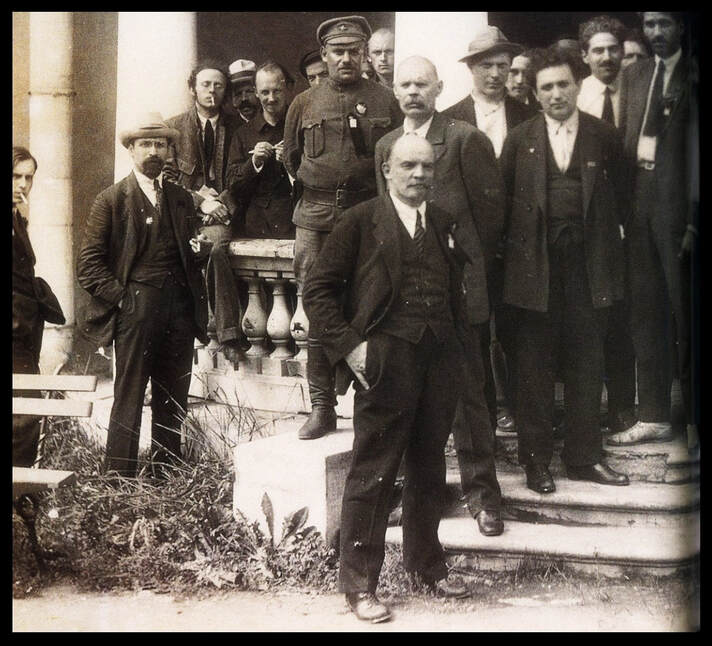

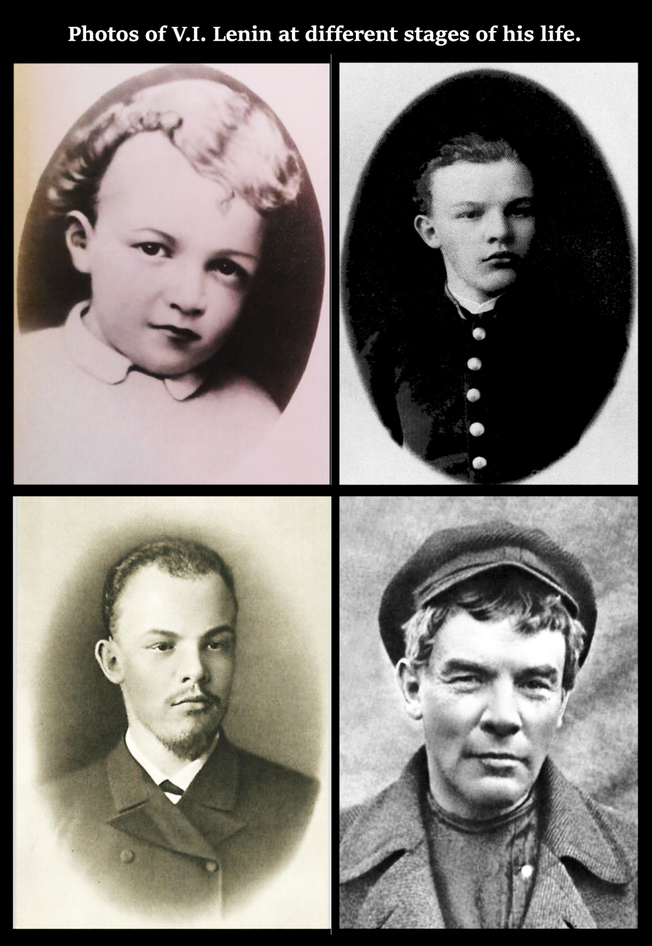

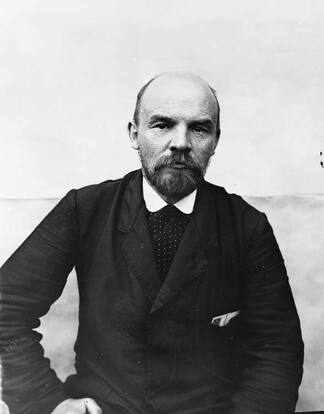

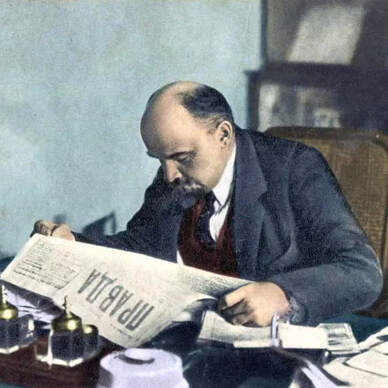

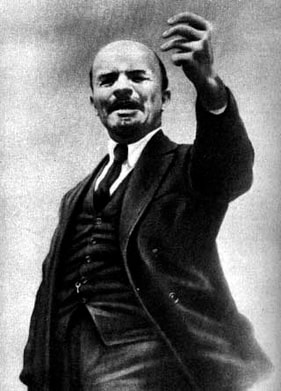

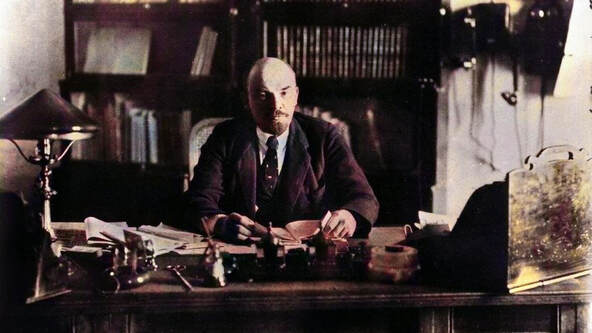

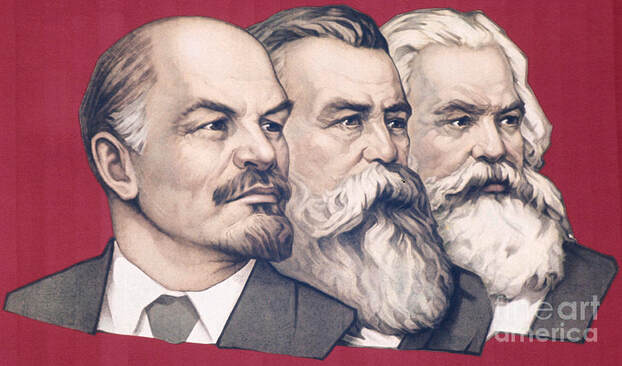

What does Lenin say to us in today’s post-Soviet world and what is his legacy, asks VIJAY PRASHAD MAKING A POINT: VI Lenin in Teatralnaya Square (then Sverdlov Square), on May 5 1920,where a parade of the Moscow garrison troops took place and, right, portrait Photo: (L to R) Grigory Petrovich Goldstein/CC andmPavel Zhukov/CC VLADIMIR ILYICH ULANOV (1870-1924) was known by his pseudonym — Lenin. He was, like his siblings, a revolutionary, which in the context of tsarist Russia meant that he spent long years in prison and in exile. Lenin helped build the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party both by his intellectual and his organisational work. Lenin’s writings are not only his own words, but the summation of the activity and thoughts of the thousands of militants whose path crossed his own. It was Lenin’s remarkable ability to develop the experiences of the militants into the theoretical realm that shaped what we call Leninism. It is no wonder that the Hungarian Marxist Gyorgy Lukacs called Lenin “the only theoretician equal to Marx yet produced by the struggle for the liberation of the proletariat.” Building a Revolution In 1896, when spontaneous strikes broke out in the St Petersburg factories, the socialist revolutionaries were caught unawares. They were disoriented. Five years later, Lenin wrote, the “revolutionaries lagged behind this upsurge, both in their ‘theories’ and in their activity; they failed to establish a constant and continuous organisation capable of leading the whole movement.” Lenin felt that this lag had to be rectified. Most of Lenin’s major writings followed this insight. Lenin worked out the contradictions of capitalism in Russia (Development of Capitalism in Russia, 1896), which allowed him to understand how the peasantry in the sprawling tsarist empire had a proletarian character. It was based on this that Lenin argued for the worker-peasant alliance against tsarism and the capitalists. Lenin understood from his engagement with mass struggle and with his theoretical reading that the social democrats — as the most liberal section of the bourgeoisie and the aristocrats — were not capable of driving a bourgeois revolution let alone the movement that would lead to the emancipation of the peasantry and the workers. This work was done in Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution (1905). Two Tactics is perhaps the first major Marxist treatise that demonstrates the necessity for a socialist revolution, even in a “backward” country, where the workers and the peasants would need to ally to break the institutions of bondage. These two texts show Lenin avoiding the view that the Russian Revolution could leapfrog capitalist development (as the populists — narodniki — suggested) or that it had to go through capitalism (as the liberal democrats argued). Neither path was possible nor necessary. Capitalism had already entered Russia — a fact that the populists did not acknowledge — and it could be overcome by a worker and peasant revolution — a fact that the liberal democrats disputed. The 1917 Revolution and the Soviet experiment proved Lenin’s point. Having established that the liberal elites within tsarist Russia would not be able to lead a worker and peasant revolution, or even a bourgeois revolution, Lenin turned his attention to the international situation. Sitting in exile in Switzerland, Lenin watched as the social democrats capitulated to the warmongering in 1914 and delivered the working-class to the world war. Frustrated by the betrayal of the social democrats, Lenin wrote an important text — Imperialism — which developed a clear-headed understanding of the growth of finance capital and monopoly firms as well as inter-capitalist and inter-imperialist conflict. It was in this text that Lenin explored the limitations of the socialist movements in the West — with the labour aristocracy providing a barrier to socialist militancy — and the potential for revolution in the East — where the “weakest link” in the imperialist chain might be found. Lenin’s notebooks show that he read 148 books and 213 articles in English, French, German, and Russian to clarify his thinking on contemporary imperialism. Clear-headed assessment of imperialism of this type ensured that Lenin developed a strong position on the rights of nations to self-determination, whether these nations were within the tsarist empire or indeed any other European empire. The kernel of the anti-colonialism of the USSR — developed in the Communist International (Comintern) — is found here. The term “imperialism,” so central to Lenin’s expansion of the Marxist tradition, refers to the uneven development of capitalism on a global scale and the use of force to maintain that unevenness. Certain parts of the planet — mostly those that had a previous history of colonisation — remain in a position of subordination, with their ability to craft an independent, national development agenda constrained by the tentacles of foreign political, economic, social and cultural power. In our time, new theories have emerged that suggest that the new conditions no longer can be understood by the Leninist theory of imperialism. Some people on the left reject the idea of the neocolonial structure of the world economy, with the imperialist bloc — led by the United States — using its every source of power to maintain this structure. Others, even on the left, argue that the world is now flat and that there is no longer a global North that oppresses a global South, and that the elites of both zones are part of an international bourgeoisie. Neither of these objections stand when confronted with both the increasing levels of violence perpetuated by the imperialist bloc and by the increasing levels of relative inequality between North and South (despite the growth of capitalist elites in the South). Elements of Lenin’s Imperialism are, of course, dated — it was written 100 years ago — and would require careful reworking. But the essence of the theory is valid — the insistence on the tendency of capitalist firms to become monopolies, the ruthlessness with which finance capital drains the wealth of the global South, and the use of force to contain the ambitions of countries of the South to chart their own development agenda. One of Lenin’s most vital interventions, which appealed to those in the colonies, was the idea that imperialism would never develop the colony, and that only the socialist forces in collaboration with the national liberation sections would be capable of both fighting for national independence and then advancing their countries to socialism. Lenin’s fierce anti-colonial determination drew his ideas to those in the colonised world, which is why they rallied so enthusiastically to the Comintern after 1919. Ho Chi Minh read the Comintern’s thesis on national and colonial issues and wept. It was a “miraculous guide” for the struggle of the people of Indochina, he felt. “From the experience of the Russian Revolution,” Ho Chi Minh wrote, “we should have to people — both the working-class and the peasants — at the root of our struggle. We need a strong party, a strong will, with sacrifice and unanimity at our centre.” “Like the brilliant sun,” Ho Chi Minh wrote, “the October Revolution shone over all five continents, awakening millions of oppressed and exploited people around the world. There has never existed such a revolution of such significance and scale in the history of humanity.” Finally, Lenin spent the period from 1893 to 1917 studying the limitations of the party of the old type — the social democratic party. Lenin’s text — Our Programme — makes the point that the party must be involved in continuous activity and not rely upon spontaneous or initial [stikhiinyi] outbreaks. This continuous activity would bring the party into intimate and organic touch with the working-class and the peasantry as well as help to germinate the protests that then might take on a mass character. It was this consideration that led Lenin to work out his understanding of the revolutionary party in What is To Be Done? (1902). The remarkable intervention highlighted the role of the class-conscious workers as the vanguard of the party and the importance of political agitation among workers to develop a genuinely powerful political consciousness against all tyranny and all oppression. The workers, Lenin argued, need to feel the intensity of the brutality of the system and of the importance of solidarity. These texts — from 1896 to 1916 — prepared the terrain for the Bolsheviks and Lenin to understand how to operate during the struggles in 1917. It is a measure of Lenin’s confidence in the masses and to his theory that Lenin wrote his audacious pamphlet Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power? a few weeks before the seizure of power. Building a state Having prevailed, Lenin now had to confront the problems of building a socialist project in the former tsarist empire, which had been devastated by its avarice and by the war. Before the Soviets had time to organise themselves, the imperialists attacked from all directions. Direct interventions on behalf of the peasants and workers, as well as national minorities, prevented large-scale defections from the new revolution to the counter-revolutionaries' armies. The peasants, with their limited means, held fast to the new beginning. But that was the point — the “limited means.” How does one build socialism in a poor country, with social development held down by the tsarist autocracy? A close reading of State and Revolution (1918) anticipates the problems faced by the Soviets in their new task — they could not only inherit the state structure, but had to “smash the state,” build a new set of institutions and a new institutional culture, create a new attitude by the cadre towards the state and society. In April 1918, Lenin’s The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government summarises the work of the first few months and shows that the Soviets were well-aware of the deep problems that they had to confront. Their revolution did not take place in an advanced capitalist country, but in what Marx had called the “realm of scarcity.” To increase the productive forces and to socialise the means of production at the same time was a task of immense proportions. “Without literacy,” Lenin wrote, “there can be no politics. There can only be rumours, gossip, and prejudice.” What limited resources were there before the Soviet state went toward literacy, with the party cadre determined to ensure that they turn around the fact that only a third of men were literate and less than a fifth of women. Between the Likbez campaign and the policy of indigenisation (korenizatsiya), the use of regional and minority languages, the Soviets were able — in two decades — to ensure that literacy levels rose to 86 per cent for men and 65 per cent for women. The centrality of workers and peasants to building Soviet Russia is often forgotten (Mikhail Kalinin came from a peasant family; Joseph Stalin came from a family of cobblers and housemaids). Education, health, housing and control over the economy as well as cultural activities and social development were the heart of the work of the new Soviet Russia, led by Lenin. No amount of right-wing drivel about the Soviet Union can erase the immense achievement of this workers’ state. In the last year of his life, Lenin wrote four formidable texts: “On Cooperation,” “Our Revolution,” “How We Should Reorder the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection,” and “Better Fewer, But Better.” In these texts, Lenin acknowledged the difficulties in the process of transformation of capitalism to socialism. He wrote of the “enormous, boundless significance” of co-operative societies, the need to rebuild the productive base and to build societies to advance the confidence of the masses. What Lenin indicated was the need for a cultural transformation, a new way of life for the workers and the peasants, and new and creative ways for the workers and peasants to have power over their society and to build their clarities in action. The workers have inherited the architecture of a hideous state, and this must be totally transformed. But how? Lenin’s reflection in Better Fewer, but Better is fiercely honest: “What elements have we for building this apparatus? Only two. First, the workers who are absorbed in the struggle of socialism. These elements are not sufficient educated. They would like to build a better apparatus for us, but they do not know how. They cannot build one. They have not yet developed the culture required for this; and it is culture that is required. Nothing will be achieved in this by doing things in a rush, by assault, by vim or vigour, or in general, by any of the best human qualities. Secondly, we have elements of knowledge, education, and training, but they are ridiculously inadequate compared with all other countries.” In his last public appearance — at the Moscow Soviet in November 1922 — Lenin praised the achievements of the young Soviet Republic, but also cautioned about the hard path forward. “Our party,” he said, “a little group of people in comparison with the country’s total population, has tackled this job. This tiny nucleus has set itself the task of remaking everything, and it will do so.” But this is not just the task of the party, but of the workers and peasants, who see the new Soviet apparatus as their own. “We have brought socialism into everyday life and must here see how matters stand. That is the task of our day, the task of our epoch.” The Soviet Union lasted only 74 years, but in those years, it experimented fiercely to overcome the wretchedness of capitalism. Seventy-four years is the average global life expectancy. There was simply not enough time to advance the socialist agenda before the USSR was destroyed. But Lenin’s legacy is not merely in the USSR. It is in the global struggle to transcend the dilemmas that confront humanity by advancing to socialism. AuthorVijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is the author of Red Star Over the Third World (Pluto Press) and Washington Bullets: A History of the CIA, Coups, and Assassinations (Monthly Review Press). This article was produced by Morning Star. Archives January 2024

0 Comments