|

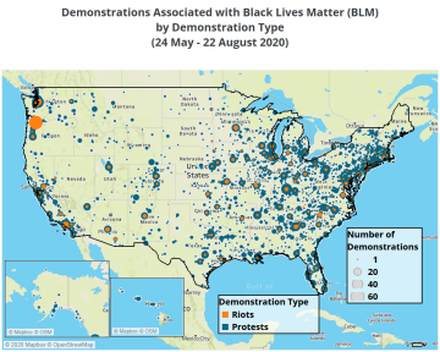

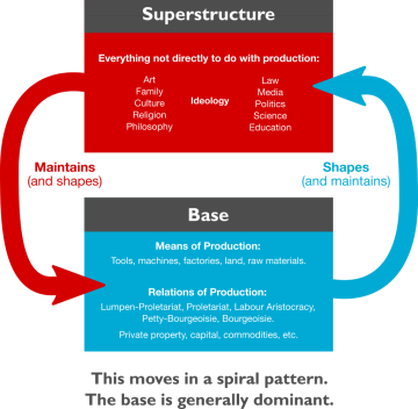

There's something happening here But what it is ain't exactly clear There's a man with a gun over there A-telling me, I got to beware.. Paranoia strikes deep Into your life it will creep It starts when you're always afraid Step out of line, the man come and take you away We better stop Children, what's that sound? Everybody look what's going down -Buffalo Springfield For What It’s Worth The year 2020 saw unprecedented waves of political activism. Between 15 and 26 million people participated in the demonstrations, making this happening the largest movement in American history. The Women’s March of 2017 had 3 to 5 million on a single day, even as a highly organized event, which reflected the scale and scope of the Summer Demonstrations.1 The murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police spurred outrage across the United States and brought an unprecedented wave of support for structural police reform. The Summer Demonstrations of 2020 were met by tear gas, rubber bullets, beatings, and in some places, protesters were arrested by federal law enforcement on suspect grounds and without explanation, identification, or acknowledgement of Miranda rights. In lay terms, citizens were taken off the streets without concern for legality by the Department of Homeland Security.2 These acts of state violence were unusual, we didn’t see these methods employed at the Women’s March of 2017 or March for Our Lives of 2018, although they were also demonstrations of unprecedented size. The recent protests are different in that their discourse threatens the very ability of the state to reproduce its own hegemony by functioning on ideology and repression. The Summer Demonstrations called for structural change: we did not believe that police training reform or individual accountability of police officers is sufficient for the desired change, these issues are rooted in the history of the institution of policing itself. The object of desire is not reformist, it is structural- it is revolutionary. The rhetoric of the 2020 Summer Demonstrations challenged the way we think about police and state, our opinions and assumptions; they challenged the discourse of American politics, and in doing so have threatened the stability of the hegemonic ideology, which is to say the state ideology. When the people begin to threaten state ideology, the Repressive State Apparatus serves to defend it with force to deter further action- acting on repression primarily, and ideology secondarily. A threat to state ideology, in the spatial metaphor of the edifice, is lifting the veil on the superstructure where ideology is determined by the base (means and relations of production) and is a step in the development of class consciousness. This paper will build off the spatial metaphor using Althusser’s structural theory to identify how ideology can be threatened, and how the state responds to it when threatened. Marx’s spatial metaphor of the edifice is his explanation of how our material existence (means and relations of production, I.e class structure, centralization of capital, private ownership) determines our social existence (socio-political structures, legal structures, ideology, ideological state apparatuses). By the logic of his metaphor, if the base undergoes a change, the superstructure will be shaped accordingly. Inversely, if the superstructure is changed, then the base may come to reflect these changes. The base heavily determines the superstructure in Marx’s metaphor, but the superstructure doesn’t quite share the same deterministic strength. The superstructure may push and nudge, but not necessarily move. Change in the superstructure undermines the ground upon which the base is maintained. As a deterministic factor, the base resists change from the structures it determines, but if it is no longer capable of determining ideology, then its cycle of reproduction is endangered. In “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” Louis Althusser elaborates on Marx’s spatial metaphor to explore ideology and identify what he calls the Ideological State Apparatus. He first remarks that “for each [Ideological State Apparatus], the various institutions and organizations comprising it form a system.” He proceeds, “If this is right, we cannot discuss any one component part of an ISA without relating it to the system of which it is a part. For example, we cannot discuss a political party, a component part of the political ISA, without relating it to the complex system of the political ISA... An ideological state apparatus is a system of defined institutions, organizations, and the corresponding practices. Realized in the institutions, organizations, and the corresponding practices. Realized in the institutions, organizations, and practices of this system is all or part of the state ideology. The ideology realized in an ISA ensures its systemic unity on the basis of an anchoring in material functions specific to each ISA.”4 Systems, however, do not evolve or change on their own- an external force must break their cyclical motion. Althusser writes, “ideology ‘functions’ at its most concrete level, the level of individual ‘subjects’: that is, people as they exist in their concrete individuality, in their work, daily lives, acts, commitments, hesitations, doubts, and sense of what is most immediately self-evident.”5 This implies a few important things. First, that ideological apparatuses do not exist in isolation- they are inextricably tied together into the system which Althusser calls the Ideological State Apparatus, or ISA for short. Therefore, a shift in one ideological apparatus impacts the Ideological State Apparatus as a whole, which in turn has the ability to influence the base it emerged from. Goran Therborn elaborates on Althusser’s idea, which is that ideology functions on the level of individuals. If we accept this, then we are bound to admit that individuals have the capacity for agency in the realm of ideology. Therborn writes that “to conceive a text or an utterance as ideology is to focus on the ways it operates in the formation and transformation of human subjectivity.”6 Therborn here recognizes that humans can dissociate from their ideology to examine how an idea or process contributes to their own subjection by the hegemonic class. If this is true, that we are able to examine how our ideology contributes to subjection from the ruling class, and that we have agency within the ideological realm, then class consciousness can develop and ideology can be found as a site of class struggle. The protests of Summer 2020 did exactly this- challenge the individual's notion of what is usually taken as self-evident; the object being challenged, of course, was the police apparatus. Ideologies operate in a matrix of sanction and affirmation, with this matrix determining a relationship.7If a subject fails to act predictably under the hegemonic ideology, then their stance is in contrast to the powers surrounding them: it is a stance of defiance. Therborn holds that emerging ideologies only rise out of those which already exist. This process of ideological change is dependent upon non-ideological, material changes, and that the most important material change is in modes of production and internal social dynamics.8 The rhetoric of the Summer Demonstrations did not address economic productive forces, but it did address radical change in the internal social dynamics of the United States. Protesters and activists did not call on justice for individual police officers, but for structural reform in policing and carceral institutions: demilitarization of police, defunding police to allow for greater social programs, dismantling legal codes which disproportionately target racial minorities, and abolition of carceral institutions which target racial minorities in favor of greater social programs. These measures are but a step towards dismantling structural racism, however they are heavy attacks on the foundations of policing and incarceration in American society. Therborn writes, “In conformity with the dialectics of history, the processes of social reproduction are at the same time processes of social revolution; revolutions occur when the latter become stronger than the former.”9 This suggests that as new ideologies emerge from the old ones, a revolutionary shift in discourse can overtake the old ones if they become strong enough and accepted enough by the masses. When the Repressive State Apparatus takes action in these instances, one can be sure that the emerging discursive shift functions as a threat to the old social order. The threat of a revolutionary discursive shift can be seen in the great social movements of American history, particularly during the Vietnam War and Civil Rights era and Battle of Seattle. When the ideological state apparatus is threatened, it relies on the Repressive State Apparatus, or RSA, as its secondary mode of reproduction. The Repressive State Apparatus is that which relies directly or indirectly on physical violence. ISAs rely primarily on ideology as its own method of sustaining itself as a system, which is to say its reproduction. The scholastic apparatus or religious apparatus do not use physical violence, conforming to them is considered an act of one's own free will, though ideology places pressure on the individual to do so. An ideological apparatus does not even have recourse for violence, its secondary function on repression comes through a separate repressive apparatus. The Repressive State Apparatus follows the same structure as the Ideological State Apparatus: it is made up of several repressive apparatuses, eg police, national guard, military, intelligence organizations, the state, carceral institutions, etc. These apparatuses are separate and operate within their own realms, but function as a singular entity in which a change in one must change the Repressive State Apparatus as a whole.10 When ideology fails to adequately defend itself, the RSA mobilizes to put down dissent, and in-so-doing discredits the dissenting party through the spectacle of force. When the RSA mobilizes, eg with riot police, national guard, etc, the dissenting party becomes discredited through the individual’s notions of state legitimacy. State action assumes legitimacy, thus when the state responds to dissent, the people believe the state to be justified in its actions and assume that the dissenting party is out of line. This is the symbolic value of state repression which relies on ideology. The RSA relies primarily on violence, crushing dissent with tear gas, crowd dispersion, and brute force, and relies secondarily on the symbolic value of its action as a function of ideology. People believe the state to be justified and the dissenting party to be invalid based on the state’s assumed legitimate use of force. This symbolic discreditation is exemplified with the historiography of the Seattle WTO protests of 1999. Often referred to as the Battle of Seattle, the anti-globalization protests took place alongside the beginning of a new round of trade negotiations for the new millennium. This protest was created at the grassroots level, partnering with labor organizations like the AFL-CIO and various national and international NGOs. Anticapitalistic at heart, the protest sought to air grievances about the emerging globalized mode of production. Some vandalism occurred, and police retaliation was heavy- thus began the battle for the story of Seattle. After the protest had ended, the Pentagon hired the Rand Corporation “to produce a study, in which the movement was described as ‘the NGO swarm,’ difficult for governments to deal with because it has no leadership or command structure and ‘can sting a victim to death.’ Corporate public relations consultants Burson Marsteller published a ‘Guide to the Seattle Meltdown’ to help its clients like [the Monsanto Company] ‘defend’ themselves.’”11 In the wake of the protest, activists fought corporate media against government disinformation campaigns used to “stoke public fears and justify repression against grassroots movements.”12 Media outlets focused on the small group of “black bloc” self-described anarchists, instead of the tens of thousands of citizens who rose up with anti-corporate sentiment and were met with tear gas and police blockades because of a number of broken windows. This exaggeration of the destructive aspect and building it as the hegemonic narrative serves the purpose of discrediting the protesters. In January 2000, a Business Week opinion poll showed that despite the disinformation efforts, 52% of Americans sympathized with the protesters. This kind of myth is created to increase acceptance of the curtailing of civil liberties towards even the peaceful protesters by mere association.13 Similar disinformation was pushed by the Trump Administration in response to the Summer Demonstrations. Data analysis by the US Crisis Monitor, a joint project by The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project and Princeton University reports: Research from the University of Washington indicates that this disparity stems from political orientation and biased media framing (Washington Post, 24 August 2020), such as disproportionate coverage of violent demonstrations (Business Insider, 11 June 2020; Poynter, 25 June 2020). Groups like the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) have documented organized disinformation campaigns aimed at spreading a “deliberate mischaracterization of groups or movements [involved in the protests], such as portraying activists who support Black Lives Matter as violent extremists or claiming that antifa is a terrorist organization coordinated or manipulated by nebulous external forces” (ADL, 2020).14 The report suggests that some violence was not perpetrated by protesters, but by those who wish to paint the protesters as violent: During a demonstration on 27 May in Minneapolis, for example, a man with an umbrella — dubbed the ‘umbrella man’ by the media and later identified as a member of the Hells Angels linked to the Aryan Cowboys, a white supremacist prison and street gang — was seen smashing store windows (Forbes, 30 May 2020; KSTP, 28 July 2020). It was one of the first reports of destructive activity that day, and it “created an atmosphere of hostility and tension” that helped spark an outbreak of looting following initially peaceful protests, according to police investigators, who believe the man “wanted to sow discord and racial unrest” (New York Times, 28 July 2020).15 The report also identifies repression against reporters. The group Reporters Without Borders have identified “an unprecedented outbreak of violence” against reporters, with over 100 separate incidences of government sponsored violence against journalists documented in 31 states and the District of Columbia during demonstrations associated with Black Lives Matter.16 It would appear that the disinformation campaign has been rather successful, given that 42% of respondents to a FiveThirtyEight poll believe “most [BLM] protesters are trying to incite violence or destroy property,” even when statistics show that counterprotests by the right have a 12% rate of violent occurrences, as opposed to the 5% on the part of Black Lives Matter protesters at over 10,600 protests, with 93% having no violence at all by either side of the political spectrum. In urban areas where more violence has occurred, like Portland, Oregon, “violent demonstrations are largely confined to specific blocks, rather than dispersed through the city.”17 These disinformation efforts are a site of ideological conflict, a battle for the truth of a narrative. When one thinks of violence, one thinks of crime, terrorism, war, civil unrest. However, viewing violence only by its visible, subjective form with identifiable agents denies the existence of the background, objective violence which creates a space for these visible, subjective outbursts.18 This way of thinking allows us to identify that which sustains violence as it tends to be understood. This objective violence is that which is inherent to the “normal” state of daily life, often called systemic violence. Slavoj Zizek says that this objective violence is like the “notorious ‘dark matter’ of physics, the counterpart to an all-too-visible subjective violence. It may be invisible, but it must be considered if one is to make sense of what otherwise seems to be ‘irrational’ explosions of subjective violence.”19 When one thinks of ideology, one doesn’t think of the norms of daily life. One tends to recognize only extreme acts as those explicitly ideologically marked, but the Hegelian point here would be that it is precisely those things which are not questioned and accepted without critical thought, that are the truest manifestations of ideology. This seemingly neutral background to the state of affairs is where this objective violence is found.20 Objective violence functioning in those things perceived as neutral is where we look again at repressive apparatuses. When the RSA mobilizes, it is believed to be just through the assumption of state legitimacy, even if the methods are more extreme. The US Crisis Monitor reports: Overall, ACLED data indicate that government forces soon took a heavy-handed approach to the growing protest movement. In demonstrations where authorities are present, they use force more often than not. Data show that they have disproportionately used force while intervening in demonstrations associated with the BLM movement, relative to other types of demonstrations. Despite the fact that demonstrations associated with the BLM movement have been overwhelmingly peaceful, more than 9% — or nearly one in 10 — have been met with government intervention, compared to 3% of all other demonstrations. Authorities have used force — such as firing less-lethal weapons over 54% of the demonstrations in which they have engaged.21 The report continues: The escalating use of force against demonstrators comes amid a wider push to militarize the government’s response to domestic unrest, and particularly demonstrations perceived to be linked to left-wing groups like Antifa, which the administration views as a “terrorist” organization (New York Times, 31 May 2020). In the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s killing, President Trump posted a series of social media messages threatening to deploy the military and National Guard to disperse demonstrations, suggesting that authorities should use lethal force if demonstrators engage in looting (New York Magazine, 1 June 2020). The president called governors “weak” for allowing demonstrations in their states and instructed them to call in the National Guard to “dominate” and “cut through [protesters] like butter” (Vox, 2 June 2020).22 The seemingly neutral object of criticism by the protesters is structural racism and police brutality, inherent to police modes of operation and the prison industrial complex. These practices are left as a result of the limitations of the Civil Rights Movement. Angela Davis writes, “we not only needed to claim legal rights within the existing society but also to demand substantive rights- in jobs, housing, healthcare, education, etc- and to challenge the very structure of society.”23 The Civil Rights Movement was able to demand legal progress, but ideology does not change as quickly, especially when racism has been used to maintain divisions in society for two and a half centuries. Angela Davis writes “the Civil Rights movement was very successful in what it achieved: the legal eradication of racism and the dismantling of the apparatus of segregation. This happened and we should not under-estimate its importance. The problem is that it is often assumed that the eradication of the legal apparatus is equivalent to the abolition of racism. But racism persists in a framework that is far more expansive, far vaster than the legal framework.”24 White American racist ideology “exerts a performative efficiency. It is not merely an interpretation of what blacks are, but an interpretation that determines the very being and social existence of the interpreted subjects,” as white America has been the dominant demographic for the duration of its existence.25 Racism, in this way, is exemplary of how ideology determines social existence. This is the process of ideological interpellation, by which an individual subject is created through its positionality within the hegemonic ideology. Legal code may change, but Louis Althusser writes that “law is indifferent to whether it is approved or condemned: law exists and functions, and can only exist and function, formally.”26 Thus, racism can only be effectively “checked” by law formally. In our concrete reality however, simply because something is bound by law does not mean that it will be either obeyed or enforced, or that the interpellated subject ceases to be subjected as such. Therborn writes, “a historical materialist conception of ideology, it would seem, involves the not very far-fetched assumption that human beings tend to have some capacity for discriminating between enunciation of the existence or possibility of something... and the actual existence/occurrence of what is enunciated.”27 Police brutality and incarceration rates reflect structural racism in American legal code, law enforcement, and carceral institutions, yet most white Americans are rather blind to the structural racism inherent to their institutions. The Summer 2020 Demonstrations showed the consciousness of the demonstrators in their recognizing that the enunciation of racism in America does not align with the existence of racism in America. In short, that the idea of a post racial America is a farce: the people have separated fact from fiction. The fifth chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s, Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin once said that “violence is as American as cherry pie.”28 When peaceful demonstrations do not produce desired results and law enforcement uses force to repress dissent, protests turn more disruptive.29 The social conditions of the United States have not been created; they have been passed down. Class based tensions, almost always intersected with race in the United States, rear their heads in defiance at every epoch: the Tulsa Massacre of 1921, the social movements of the 1960s, again with the expansion of globalized production in the late 90s, and now with the Black Lives Matter movement amidst cries for structural change. We have not made history as we please, but by the circumstances directly transmitted from national past.30 However, something is notably different: the extent to which these crowds were anti-capitalist and intersectional. Crowds chanted against structural racism, monuments of white supremacy, the rise of right-wing populism, the resurgence of white supremacy, and the role of class within systems of domination and exploitation. With Black, White, Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous peoples, as well as the support of the LGBTQ+ community, the intersectionality of the masses implies solidarity and commonality of interest- intersectionality transcends solidarity and steps towards class consciousness.31 This is not a factor that has been quite so significant throughout American history, and presents a unified people engaged in social revolution.32 The Summer Demonstrations of 2020 have openly declared that their ends can only be attained by the structural change of existing repressive apparatuses. Now, they represent the interests of the working class and all oppressed minorities, “but in the movement of the present, they also represent and take care of the future of that movement.”33 Citations 1 Buchanan, Larry, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel. “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 3, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html. 2 Kishi, Roudabeh. “Demonstrations & Political Violence in America: New Data for Summer 2020.” ACLED. Princeton University, November 5, 2020. https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in america-new-data-forsummer-2020/. 3 Ibid. 4 Althusser, Louis. On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. P. 76- 7. Translated by G. M Goshgarian. London: Verso, 2014. 5 Ibid., P.176. 6 Therborn, Goran. The Ideology of Power and the Power of Ideology. P. 34. London: Verso, 1980. 7 Ibid., P. 33. 8 Ibid., P. 44. 9 Therborn, Goran. What Does the Ruling Class Do When It Rules? P. 176. London: Verso, 1980. 10 Althusser, Louis. On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. P. 78. Translated by G. M Goshgarian. London: Verso, 2014. 11 Solnit, David, Rebecca Solnit, and Anuradha Mittal. The Battle of the Story of the Battle of Seattle. P. 1. Edinburgh: AK Press, 2009. 12 Ibid., P. 5. 13 Ibid., P. 15. 14 Kishi, Roudabeh. “Demonstrations & Political Violence in America: New Data for Summer 2020.” ACLED. Princeton University, November 5, 2020. https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in america-new-data-forsummer-2020 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 Ibid. 18 Zizek, Slavoj. Violence. P. 1. London: Profile Books, 2009. 19 Ibid. 20 Ibid., P. 36. 21 Kishi, Roudabeh. “Demonstrations & Political Violence in America: New Data for Summer 2020.” ACLED. Princeton University, November 5, 2020. https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in america-new-data-forsummer-2020/. 22 Ibid. 23 Davis, Angela. Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. P. 36. Haymarket Books, 2016. 24 Ibid., P. 16. 25 Zizek, Slavoj. Violence. P. 72. London: Profile Books, 2009. 26 Althusser, Louis. On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. P. 59. Translated by G. M Goshgarian. London: Verso, 2014. 27 Therborn, Goran. The Ideology of Power and the Power of Ideology. P. 34. London: Verso, 1980. 28 Sugrue, Thomas. “2020 Is Not 1968: To Understand Today's Protests, You Must Look Further Back.” History & Culture, August 25, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/06/2020- not-1968/. 29 Ibid. 30 Tucker, Robert C., Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels. ”18th Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte.” P. 595. In The Marx Engels Reader. New York: Norton, 1978. 31 Davis, Angela. Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. P. 18-9, 39. Haymarket Books, 2016. 32 Sugrue, Thomas. “2020 Is Not 1968: To Understand Today's Protests, You Must Look Further Back.” History & Culture, August 25, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/06/2020- not-1968/. 33 Tucker, Robert C., Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels. "Manifesto of the Communist Party.” P. 500. In The Marx Engels Reader. New York: Norton, 1978. About the Author:

Joseph Senecal is a student completing undergraduate research in international studies and political science at Flagler College in St. Augustine, Florida. McCann is interested in structuralism, post-structuralism, ideology, revolutionary history, and translation. Particularly inspired by French structuralist and existentialist writers of the 1960s, McCann hopes to translate works that have yet to be put in English for an American audience. Applying to doctoral programs in philosophy and political science, McCann hopes to continue his education in Marxian thought. In his personal life, he works as a cook, enjoys blues rock, and has an adored cat named Carlos Santana.

0 Comments

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed