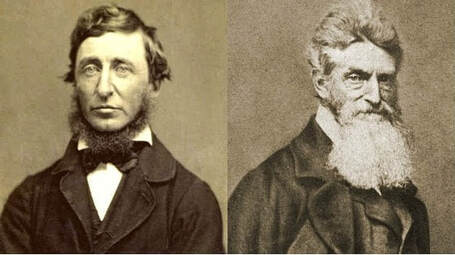

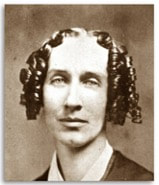

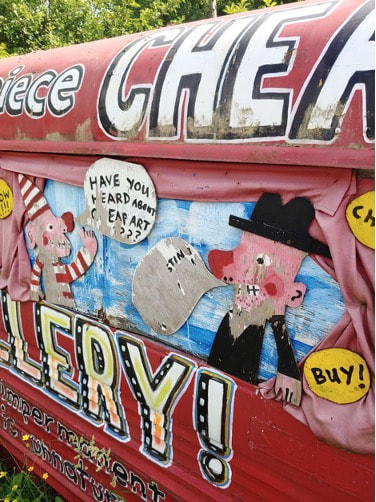

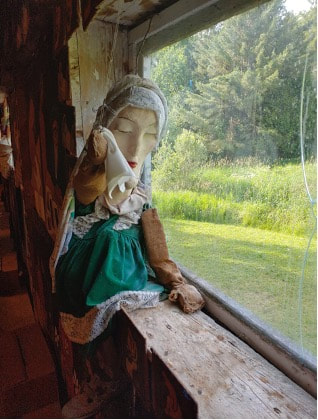

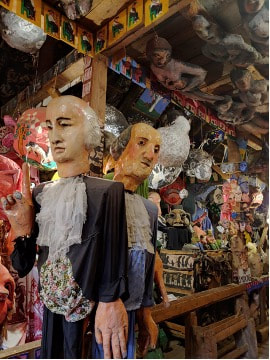

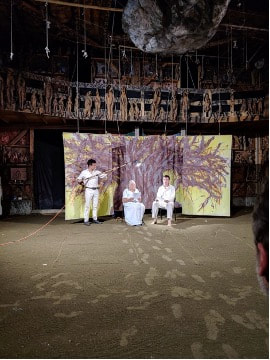

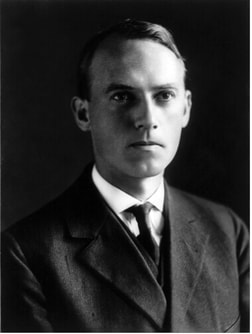

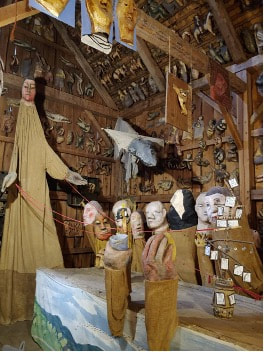

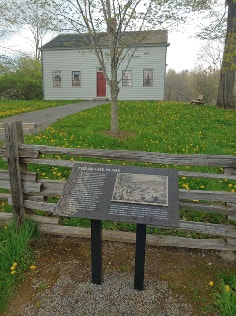

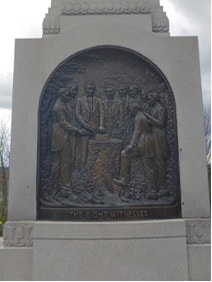

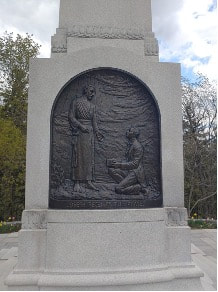

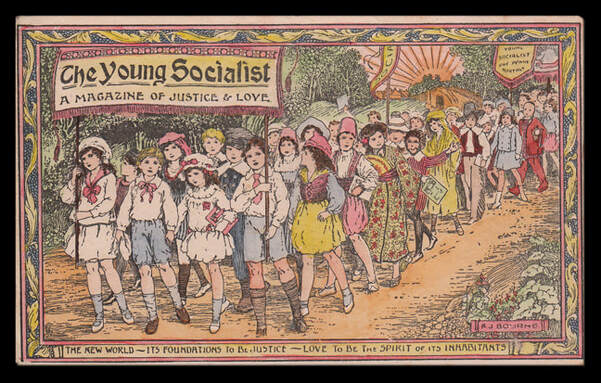

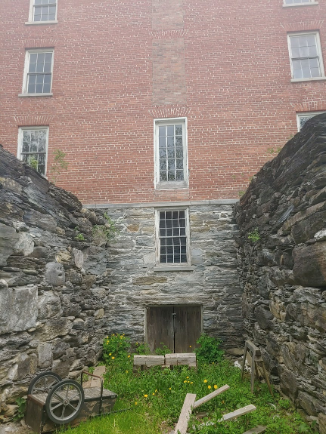

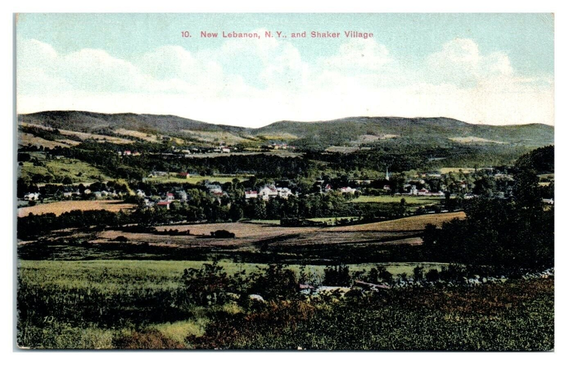

“To be a possibilitarian is to acknowledge that any of the thousand alternatives to capitalism is possible.” – Bread and Puppet Theater. I wrote these entries when I first visited in the summer of 2019 with some updates from my trip in 2021. My wife and I planned a series of trips in 2019. In addition to the sites reviewed here, we also spent a few days in Montreal. I considered writing up something about the Quebecois nationalists like the Marxist-Leninist Front de libération du Québec who engaged in kidnappings of politicians and bombings to bring about an independent, socialist Quebec.[1] However, as a result of language and geographical confusion, that trip was hectic, so I chose not to write anything up about that leg of the journey. Besides, I do not really feel like I have much to say on the situation. Let Anglophone and Francophone Canadians fight it out. My anthropological observations as an outsider indicated that there is definitely a class divide between Francophones and Anglophones. The people that worked in the museums and galleries tended to speak both English and French fluently, while restaurant and grocery workers tended to speak exclusively French. I have heard that some bilingual Quebecois are offended by tourists not knowing French. In my experience, if one walked into a place and tried to speak broken French, most of the time people would just start speaking to you in English. The big trip my wife and I took that year was to what is known as the Northeast Kingdom or simply the “kingdom” of Vermont. I am not necessarily impressed with the monarchist sounding moniker offered to the region in 1949 by Republican Governor George Aiken. According to a leftist resident I talked to, it is apparently known as one of the more reactionary parts of the state. Still, there were many people we saw showing their support for Independent Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described “democratic socialist,” at the time running in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary race. Even though Sanders is actually a proponent of what has historically been known as social democracy, or in America as liberalism or progressivism, his almost intentional misuse of the term socialism opens possibilities for a new kind of politics: one divorced from the Cold War discourse that blacklisted socialism and made it taboo. The possibilities offered by a Vermont “socialist” running for president seemed to have a good hold on the state of Vermont. Although we did see a Gadsden flag and a Confederate flag while we were there, we also met many far left radicals open to the thousands of possible alternatives to capitalism. Many Vermonters own guns, on both the right and the left. The state is known for its lax gun laws. It is a rural, forested state and could make a good strategic base from which to build a leftist stronghold in the northeastern United States if it was not becoming increasingly unaffordable to live there. On our way to Vermont we stopped in the Adirondack Mountains.The Adirondacks, along with the Alleghenies of Pennsylvania and the Green Mountains of Vermont, are collectively known as the Northeast Appalachians. W. E. B. Dubois wrote in his biography of John Brown: The vastest physical fact in the life of John Brown was the Alleghany [sic] Mountains – that beautiful mass of hill and crag which guards the sombre majesty of the Maine coast, crumples the rivers on the rocky soil of New England, and rolls and leaps down through busy Pennsylvania to the misty peaks of Carolina and the red foothills of Georgia. In the Alleghanies John Brown was all but born; their forests were his boyhood wonderland; in the villages he married his wives and begot his clan. On the sides of the Alleghanies he tended his sheep and dreamed his terrible dream. It was the mystic, awful voice of the mountains that lured him to liberty, death and martyrdom within their wildest fastness, and in the bosom he sleeps his last sleep.[2] It was in the Adirondacks that John Brown saw the possibility of an alternative to slavery. He sacrificed all to make it happen and even though his endeavor at Harper’s Ferry failed, it opened up another possibility for the end of slavery. It had a profound influence on the American Civil War. In 2021 we returned to these places with my daughter so that she could experience the ephemeral experience of American Socialism Travels. John Brown’s Farm – North Elba, NYphoto by Wendy Jones This statue was the first thing we saw when we arrived at the end of John Brown Road. The statue is moving. It is so simple. John Brown talking to a young black boy as though he wasn an equal was a powerful act of defiance in the 1840s and 50s. John Brown was not just an abolitionist. Many of the abolitionists did not believe in equality, they simply believed slavery was distasteful. John Brown was not one of these bourgeois abolitionists. Although he owned businesses, most of them failed. He was impoverished and the little money he did have he put into the cause of ending the enslavement of people of African descent on the North American continent. When we returned to John Brown’s Farm in 2021, they had erected a temporary cemetery in remembrance of black lives unjustly taken at the hands of police and vigilantes. It stood as a somber yet militant answer to the uprisings of 2020. The names of Amaud Arbery, George Floyd, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Amado Diallo, recent victims of state terrorism, sat mournfully alongside names like Rev. George Washington Lee and Elbert Williams, voting rights pioneers assassinated with police complicity. It was a sober reminder that John Brown’s approach, not the approach of the Democratic Party, the party of Andrew Jackson, Andrew Johnson and the Ku Klux Klan until 1964, is what is necessary to confront the racism and violence of the police. Photos by Wendy Jones One of the utopian endeavors John Brown took part in was the one that brought him to the Adirondacks. With the help of wealthy abolitionist Gerrit Smith he pioneered the black colony known as Timbuktu. It was Smith and Brown’s dream to help enfranchise free blacks. The law said that a black person could not vote in New York unless they owned 200 acres of land. It was Smith’s idea to buy land in the mountains to give to free blacks in hopes that they would be politically enfranchised and have means to farm and make money. Brown and his family moved to the Adirondacks to help with this utopian project. John Brown’s second wife and three of his youngest daughters lived at the farm in New York. Mary Ann Brown with Annie (left) and Sarah (right) about 1851.[3] After the incident at Harper’s Ferry, Brown requested his body be brought back to North Elba to be buried. He is buried there along with a few of his followers. John Brown was so influential on the abolitionist cause in the North that a song called “John Brown’s Body” became an unofficial anthem of the Union. Like “Dixie,” “John Brown’s Body” was originally meant to be satirical, but people soon began to take it quite seriously. Julia Ward Howe, poet, abolitionist, author of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” Julia Ward Howe, a poet and an abolitionist, wrote the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” based on the tune of “John’s Brown’s Body.” A Union regiment was marching early in the morning near where Howe was staying. Early in the morning she could hear them singing “John Brown’s Body” and it inspired her to write the “Battle Hymn.” She wrote: I went to bed that night as usual, and slept, according to my wont, quite soundly. I awoke in the gray of the morning twilight; and as I lay waiting for the dawn, the long lines of the desired poem began to twine themselves in my mind. Having thought out all the stanzas, I said to myself, “I must get up and write these verses down, lest I fall asleep again and forget them.” So, with a sudden effort, I sprang out of bed, and found in the dimness an old stump of a pen which I remembered to have used the day before. I scrawled the verses almost without looking at the paper.[4] It is said the Confederate troops would hear the Union Army marching to the “Battle Hymn” and know that they were really singing about John Brown. As much as the moderate Republicans like Lincoln wanted to distance unionism from abolitionism, the South believed the Republican Party was a black supremacist plot. Indeed many of the volunteers in the Union Army were militant abolitionists. Many of them were even black. And they did not just sing “Battle Hymn of the Republic'' to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.” They often sang the original lyrics, proudly and audaciously celebrating the raid on the armory at Harper’s Ferry that sparked what Karl Marx and the First International Workingmen’s Association called the American Anti-Slavery War. Henry David Thoreau and John Brown Henry David Thoreau said in his paper A Plea for John Brown: If it does not lead to a “surprise” party, if he does not gain a new pair of boots, or a vote of thanks, it must be a failure. “But he won’t gain anything by it.” Well, no, I don;t suppose he could get four-and-sixpence a day for being hung, take the year round; but he stands a chance to save a considerable part of his soul- and what a soul!- when you do not. No doubt you can get more in your market for a quart of milk than a quart of blood, but that is not the market heroes carry their blood to. Thoreau and Brown were both possibilitarians because they believed in doing the impossible to make possible alternatives to the legal slavery system, seen by many as here to stay. Clarina Howard NicholsClarina Howard Nichols We also stayed in the Green Mountain area of Vermont that same year. We got a cabin in Townshend, Vermont with my in-laws. I would soon find that Townshend itself was home to some radical history. Clarina Howard Nichols was a feminist and suffragist activist born in 1810 in Townshend. Howard begged her father to give her “an education, not a dowry.” She went to school at the Select School for gifted learners in West Townshend. In 1830 she married a lawyer named Justin Carpenter and briefly moved to Western NY to start a school for girls. In 1839 Howard petitioned the Vermont legislature for a divorce from her husband who she said “treated her with cruelty, unkindness and intolerable severity.” This experience lead her to view marriage as an oppressive, exploitative institution not dissimilar to chattel slavery. After her divorce she moved back to Townshend and wrote feminist articles for the Windam County Democrat. She married George W. Nichols, publisher of the Democrat, in 1843. By the 1850s she had gained notoriety as a feminist and wearer of the Bloomer. The Bloomer, invented by Western NY born feminist Amelia Bloomer, was a loose fitting garment known as the uniform of the feminists. It was worn as a protest against the tight garments in fashion for women at the time. In 1852 she sent a petition signed by 250 in favor of extending the right to vote, which men enjoyed, to women. She became the first woman to address the Vermont legislature that same year. She later recalled, “I went to the capitol and presented the whole subject of woman’s legal wrongs, including the denial of her mother’s rights in the custody and control of her children, and the conduct of their education in the schools, as results of her disenfranchisement.” Unfortunately, much of the criticism of Ms. Howard Nichols was in reference to her dress, not the content of her speech. This was the home Clarina Howard grew up in with her parents in Townshend. Today it is a community center, restaurant, thrift store and post office for the town of Townshend. John Humphrey NoyesJohn Humphrey Noyes, founder of the Bible Communist Community of Christian Perfectionists at Oneida, NY, was born in Putney, VT. The Perfectionists in Putney briefly formed the Putney Community before moving most of their operations to Oneida. According to the Oneida Community Mansion House: Historic Structure Report: In 1839, John Humphrey organized a ‘Bible class” of friends and family. The group evolved to become the “Putney Community” in 1846. It was among this group of 30 trusted and loyal friends and family that Noyes formulated his plan for communal living. However, objections to the radical religious group grew in Putney within the next two years and by 1847, the Putney Perfectionists were forced to seek another location. John Humphrey Noyes explains the origins of the Putney Perfectionists in the book The Putney Community: Early in 1840 the Putney Perfectionists began holding meetings on Sunday in Noyes’s own house, which was now finished. By the end of 1840 meetings were also held Wednesday evenings at the East Part and Thursday evenings at the Noyes homestead. In 1841 a chapel was built, in which after August 1st daily sessions were held. The Perfectionist chapel no longer exists in Putney. My wife and I got lost looking for Putney, but we eventually stumbled across the birthplace of John Humphrey Noyes. Our pilgrimage had taken us through forests and onto literally impassable mountain roads. Finally we stumbled across Putney by accident, as though it was divine intervention after a two hour pilgrimage. Today the Noyes home hosts the offices of the Earth Bridge Community Land Trust. A community land trust is a modern version of a utopian socialist community. In a community land trust members own the land collectively and might share some common areas and buildings while maintaining private dwellings and farms. Images of Putney’s past courtesy of the Putney General Store. The Putney General Store was established in 1796. It is said to be the oldest general store that has been consistently a general store throughout its history. It burned down twice: in 2008 and 2009.In 2009 it appeared to be arson. The Putney community got together and raised enough money to remodel the store twice. Bread and Puppet Theater – Glover, VermontThe first encounter I had with the Bread and Puppet Theater was seeing them at protests in the early 2000s. When I would go to anti-war or what at that time was called “anti-globalization” (today known as anti-neoliberal or anti-free trade) protests they would be there with these huge, expressive, cartoonish but remarkably human puppets. When you saw the Bread and Puppets puppets you knew you had made it to the protest. Peter Schumann, born in Silesia in 1934, was a sculptor and dancer in Germany before moving to the United States in 1961. In 1963, he founded the Bread and Puppet Theater in New York City.[5] I contacted Joshua Krugman, Bread and Puppet’s media liaison. When I met him he described his role as, “just a puppeteer who answers emails.” When I initially talked to Jason I had a series of questions for him about utopianism versus scientism, the state character of Vermont and John Brown. He answered, “Unfortunately I’m too strapped for time to be able to answer in prose by email. My apologies for this, and thanks for understanding.” However, he invited my wife and I to dinner with the troupe before the performance and said we could do an interview there. When we arrived at the Bread and Puppet phalanx, we immediately noticed a group of racially diverse young people, looking to be in their 20s, crossing the road with parts of some kind of large puppet. First we explored the Cheap Art Bus. Then we explored the museum. It was a brilliant display of retired puppets densely populating a series of hallways and a gallery upstairs. The Bread and Puppet Museum is open all the time. The light switches are clearly marked so that anyone can come in, turn on a light and look around. Visitors are, of course, encouraged to turn the lights off upon exit. The bathrooms are traditional outhouses, utilizing sawdust. After exploring for a short time my wife and I made our way into the dinner area behind the main house. The dinner was, of course, a communal experience. Everyone got a plate and waited in line to be served. The meal was a slightly spicy chickpea curry, which was delicious, with homemade naan and salad with a creamy dressing and a vegan option. All the food was vegetarian. The curry was one of the members’ grandmother’s recipes. We sat on the lawn and ate as guests of the phalanx. We asked around and eventually Josh found us and we sat together on the lawn, talking and eating. I started by asking Josh about Vermont’s state character. He told me there were a lot of leftists, but mostly they were liberals. Josh remarked that the “kingdom” area is more conservative than other areas of Vermont. There are a lot of far-right “Libertarian” types and gun enthusiasts. However, he remarked that pretty much everyone is really friendly and accepting. LGBT folks are welcomed in almost all parts of Vermont. I asked Josh what utopia means to him. His answer, he explained, was influenced by messianic Judaism and a quote by 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, “Live your life as though your every act were to become a universal law.” He believed utopia was in the doing, the praxis of life and art. I asked him if spirituality and politics can or should be combined. He said, “I think it depends on your spirituality. Certainly they were for someone like John Brown.” Changing hats from individual thinker to collective representative, Josh said, “I think for us, Bread and Puppet, our political praxis is this, what we’re doing here. Feeding people and sharing art with them is our political praxis.” I was also lucky enough to have a chance to speak with Peter and Elka Shumann. I told Peter about my research into Fourierism and when I started talking about phalanxes he said, “Oh yes, the phalanstery.” I explained that I am from Rochester and our town has a rich history of political radicalism. I mentioned Emma Goldman had lived there for a short time. Elka was interested to hear that. Then she told me Emma was going to be in the performance tonight. Photo by Wendy Jones I asked Elka what made her interested in left wing politics. She said, “Oh, my grandfather probably.” Her grandfather was Scott Nearing, an American radical economist. She told me he was fired from the reactionary Wharton School of Finance for opposing child labor in the mines in Pennsylvania. Socialist economist and simple living advocate Scott Nearing Elka grew up in the Soviet Union. Her family moved in the New York City in 1941 to escape a Nazi invasion and occupation of parts of the USSR. She met Peter in Munich in 1958.[6] In the 1970s Bread and Puppet Theater had a residency at Goddard College, but Elka said they eventually told them their residency was up. She said in the 70s Goddard College was very radical and had many radical students and faculty, but later on they became more reactionary. The famous Uncle Fatso Ultimately I wonder how much art and lifestyle can be considered political praxis. I wonder if, in some ways, supporting Bernie Sanders, far from a revolutionary act, is more praxis than putting on plays in the woods. Ultimately political praxis means trying to take power. John Brown’s political praxis was certainly so effective that it actually caused a war. I think the Bread and Puppet phalanx might prefer to march away from war altogether. Murray Bookchin’s polemic against Hakim Bey and others entitled “Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm” says: Essentially, however, anarchism as a whole advanced what Isaiah Berlin has called ‘negative freedom,’ that is to say, a formal ‘freedom from,’ rather than a substantive ‘freedom to.’ Indeed, anarchism often celebrated its commitment to negative freedom as evidence of its own pluralism, ideological tolerance, or creativity — or even, as more than one recent postmodernist celebrant has argued, its incoherence. I think the Bread and Puppet phalanx attempts to bridge this chasm, but ultimately, as Abraham Lincoln said, a house divided against itself cannot stand. It either becomes one thing or the other. In this case I fear Bread and Puppet leans more toward lifestyle anarchism. Their art and lifestyle embody the politics they believe in, but, as Josh said, they are not prefigurative. They do not believe they have a model that the world should imitate. They do what they do for their own satisfaction in feeling righteous. The theme of the show we saw was Diagonalism. I still do not know exactly what Diagonalism is, but my understanding is that it is an attempt to tip the world to one side or the other. I don’t want to tip the scales. I want to push them to one side completely. Possibilitarianism, on the other hand, the belief that any of the thousands of alternatives to capitalism are possible, that I am behind wholeheartedly. In 2021 we went to Bread and Puppet’s “Our Domestic Resurrection Circus.” It was a rainy day and the event was outside. We brought our faithful dog, Oliver, along. Oliver hates to be wet, but he was a trooper. Luckily, we took him to the Dog Chapel at Dog Mountain in Saint Johnsbury, VT earlier in the day where he got to meet some real dogs and a few fake ones. Artist Stephen Huneck conceived of the Dog Chapel and Dog Mountain after a near death experience in 1997. Its motto is “WELCOME ALL CREEDS, ALL BREEDS, NO DOGMAS ALLOWED!” Huneck wrote: ...the near-death experience, combined with what my wife taught me about love, and the appreciation I felt toward the most basic things we all take for granted had a profound effect on me. As an artist, I share the feelings I have with others through my art. One day, not long after I was back home with my wife and three dogs, a wild idea just popped into my mind (a frequent thing, but after several weeks had gone by, this one was still there).... Coming down from the high of Dog Mountain, faithful Oliver dutifully endured with us through the rain as we viewed a few side shows, one in which they burned two white flags that read “US” and “Canada.” There were a few gasps. The piece decried the violence recently literally unearthed outside several Canadian Catholic boarding schools meant to inflict cultural genocide on the First Nations peoples, where mass graves of children, abducted from their homes, were left unmarked for years. I wondered how many in the audience were actually sympathetic to revolutionary leftism. I myself wore a Fidel Castro t-shirt, but I wondered if any were offended by my brandishing of the image of a so-called “dictator.” My daughter assured me that most anarchists would probably be least offended by Fidel out of all the so-called “communist dictators.” However, I recalled that when we went to Bread and Puppet in 2019, there was a middle aged woman who was apparently a Trump supporter that had come with some friends and stormed out when the political commentary started. As much as Bread and Puppet has become somewhat of a proud Vermont tradition in the Northern Kingdom, Schumann and his phalanx have never toned down their message. “Our Domestic Resurrection Circus” at times hilarious, at times awe inspiring, contained segments defending Cuba and Palestine and denouncing capitalism, commercialism and greed. Although I felt in 2019 that Bread and Puppet was practicing lifestyle anarchism, I now understand the purpose of their art. Peter Schumann wrote in the cheap art manifesto: PEOPLE have been THINKING for too long that ART is a PRIVILEGE of the MUSEUMS and the RICH. ART is not BUSINESS! ART IS FOOD! YOU can't EAT it but it FEEDS you. ART has to be CHEAP and available to EVERYBODY... ART wakes up sleepers. ART FIGHTS AGAINST WAR and STUPIDITY! ART SINGS HALLELUJA! Schumann and his phalanx bring cheap art and simple “golden rule” morality to the people through their performances. Even the owner of the mountain cabin we stayed in, who had right wing decals on their truck, had inside the cabin a Bread and Puppet flag that just said “Yes” with an image of a rose. The Northern Kingdom knows Bread and Puppet is a unique draw to the area. Schumann and his phalanx know that if you build it, they will come and be fed on radical, political art, hopefully thinking about the world a little bit differently on the way home. Photo by Wendy Jones Works Cited [1] Lorne Weston, "THE FLQ: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF A TERRORIST ORGANIZATION," Department of Political Science, McGill University, 1989: 184. [2] W. E. Burghardt, Dubois, John Brown, (Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs and Co., 1909), 48. [3] Source: https://www.nps.gov/articles/wives-and-children-of-john-brown.htm [4] Howe, Julia Ward. Reminiscences: 1819–1899.Houghton, Mifflin: New York, 1899, 275. [5] “About B & P’s 50 Year History.” Bread and Puppet Theater. Accessed July 08, 2019. https://breadandpuppet.org/about-b-ps-50-year-history. [6] “Oral History Interview with Elka Schumann.” Digital Vermont: A Project of the Vermont Historical Society. Accessed July 08, 2019. http://digitalvermont.org/vt70s/AudioFile1970s-37. [7] “Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm.” The Anarchist Library. Accessed July 08, 2019. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/murray-bookchin-social-anarchism-or-lifestyle-anarchism-an-unbridgeable-chasm. [8] Stephen Huneck, “Huneck Vision Statement.” Huneck Vision Statement | Dog Mountain, VT - Stephen Huneck Accessed July 26, 2021, https://www.dogmt.com/Huneck-Vision-Statement.html. AuthorMitchell K. Jones is a historian and activist from Rochester, NY. He has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s degree in history from the College at Brockport, State University of New York. He has written on utopian socialism in the antebellum United States. His research interests include early America, communal societies, antebellum reform movements, religious sects, working class institutions, labor history, abolitionism and the American Civil War. His master’s thesis, entitled “Hunting for Harmony: The Skaneateles Community and Communitism in Upstate New York: 1825-1853” examines the radical abolitionist John Anderson Collins and his utopian project in Upstate New York. Jones is a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation. Archives July 2021

0 Comments