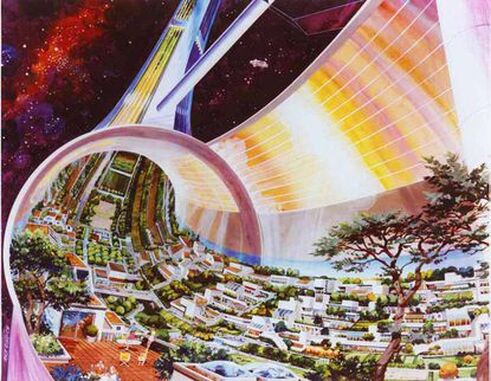

"I would annex the planets if I could; I often think of that." - Cecil Rhodes Venture capitalism is about to find itself in a new arena – space. Its existence has already started as SpaceX has begun to launch its first rockets into space. Jeff Bezos said “The only way that I can see to deploy this much financial resource is by converting my Amazon winnings into space travel. That is basically it.”[i] The rich want to get to space, and capitalists are extremely good at innovation. The development of space is inevitable and important, but the critical question is by whom. The primary avenue for wealth creation in space will be mining. The vast number of material resources available on the nearest celestial bodies[ii], combined with the potential for strip mining, means that the first few corporations to mine in space will be wildly successful. Goldman Sachs claims that the first trillionaire will make their fortune in space[iii]. After purchasing competing rocket programs to create an oligopoly on access to space itself, these companies would quickly dwarf today’s Earthbound mega-corporations. Once these corporations are off earth and recruit a space-based working-class, to which government will they answer? What would stop these corporate settlements from arming their borders, proclaiming themselves free from governance, and lobbying Earth politicians into the ground with their newfound billions? Current governments are running a deficit pay for healthcare; the notion that they could finance a fleet of rockets to enforce bureaucratic regulations in space is a fantasy. If these space-mining initiatives are powered by economic democracy, humans could have access to all the materials they require. The trove of metals and minerals would be at the behest of society as a whole, eliminating the politics of scarcity. Without such scarcity, an entire upper bound for human advancement and consumerism could disappear. Under the influence of capitalism, however, the process would be much different. The space-faring miners could flood the market and bankrupt miners on Earth repeatedly. Then, they would leverage another monopoly and most likely follow in the diamond industry’s footsteps – choking out supply to keep prices and revenue high[iv]. Space settlements would exist, but their leaders would not hold power democratically. These space settlements’ only purpose would be to generate more wealth and luxury. The existence of a ruling luxury class looking to build private kingdoms is one thing, but a more insidious issue would present itself. Everything involved with the settlement – including housing, utilities, food, and return tickets to earth– would be owned and controlled by the corporation. The company would set both the workers’ wages and the cost to leave the space settlement. It might not happen immediately, but the conditions are almost inevitably going to drift towards an exit ticket being too expensive to afford. A captive workforce with no option but to accept its wages is irresistible to any wealthy capitalist. Indentured servitude has and always will be attractive to a company’s bottom line. There’s one other problem involved with the rich and powerful holding humanity hostage in space. A society based on wealth accumulation only seeks to become more and more extravagant. The drive to explore, create, learn, and discover falls by the wayside — bottlenecked and strangled by the desire for extreme luxury. Only a society based on economic democracy will allow humanity to choose exploration and science for its own sake because sometimes, discovery doesn’t find itself in the name of wealth. Citations [i] Döpfner, M. (2018, April 28). Jeff Bezos reveals what it's like to build an empire and become the richest man in the world - and why he's willing to spend $1 billion a year to fund the most important mission of his life. Retrieved November 05, 2020, from https://www.businessinsider.com/jeff-bezos-interview-axel-springer-ceo-amazon-trump-blue-origin-family-regulation-washington-post-2018-4 [ii] Bonsor, K. (2020, June 22). How Asteroid Mining Will Work. Retrieved November 05, 2020, from https://science.howstuffworks.com/asteroid-mining.htm [iii] Business, R. T. (2018, April 22). Space mining will produce world's first trillionaire. Retrieved November 05, 2020, from https://www.rt.com/business/424800-first-trillionaire-space-miner/ [iv] Nace, T. (2018, May 30). De Beers Gives In And Begins Selling Lab Made Diamonds. Retrieved November 05, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/trevornace/2018/05/30/de-beers-gives-in-and begins-selling-lab-made-diamonds/?sh=5d5a25694636 About the Author:

Casper Rove is a blue collar worker from Omaha, Nebraska who coaches highschool debate part-time. His free time is best spent making headway in his endeavor for sustainable subsistence farming and looking for the most pragmatic way to convert socialist thought into socialist infrastructure.

4 Comments

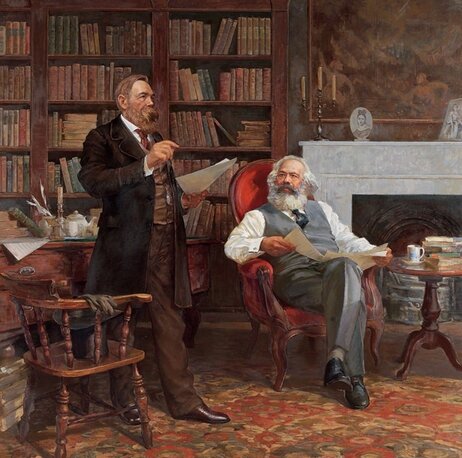

12/25/2020 An Engels Christmas: Frederick Engels and Early Christianity. By: Thomas RigginsRead NowPart 1This is the season to remind all our Christian friends of the relationship between Christianity and Marxism-Leninism and the working class movement. Engels (“On the History of Early Christianity”) tells us that there are “notable points of resemblance” between the early working class movement and Christianity. First, both movements were made up of oppressed poor people from the lower ranks of society. Christianity was a religion of slaves and people without rights subjugated by the state and very similar to the types of poor oppressed working people that founded the earliest socialist and worker’s organizations in modern times. Second, both movements held out the hope of salvation and liberation from tyranny and oppression: one in the world to come, the other in this world. Third, both movements were (and in some places still are) attacked by the powers that be and were discriminated against, their members killed or imprisoned, despised, and treated as enemies of the status quo. Fourth, despite fierce persecution both movements grew and became more powerful. After three hundred years of struggle Christians took control of the Roman Empire and became a world religion. The worker’s movement is still struggling. After its first modern revolutionary appearance as a fully self conscious movement (1848) it achieved a major impetus in the later part of the nineteenth century with the growth of the First and Second Internationals, and the German Social Democratic movement. It too is now a world wide movement with Socialist, Social Democratic and Communist parties spread around the world. [The rise and fall of the USSR was a bump in the road the consequences of which have yet to be determined.] The Book of Acts reveals that the early Christians were primitive communists sharing their goods in common and leading a collective life style. This original form of Christianity was wiped out when the Roman Empire under Constantine imposed Christianity as the official religion of the state and set up the Catholic Church in order to make sure that the religious teachings of Jesus and the early followers of his movement would be perverted to protect the interests of the wealthy and the power of the state. With few exceptions, all forms of modern day Christianity are descended from this faux version, based on a mixture of Jewish religious elements and the practices of Greco-Roman paganism, and only the modern working class and progressive movements (basically secular) carry on in the spirit of egalitarianism and socialism of the founder of Christianity. Engels points out that there were many attempts in history (especially from the Middle Ages up to modern times) to reestablish the original communistic Christianity of Jesus and his early followers. These attempts manifested themselves as peasant uprisings through the middle ages which tried to overthrow feudal oppression and create a world based on the teaching of Jesus and his Apostles. These movements failed giving rise to the state sanctioned Christianity of modern times. Engels mentions some of these movements– i.e., the Bohemian Taborites led by Jan Zizka (“of glorious memory”) and the German Peasant War. These movements are now represented, Engels points out, by the working men communists since the 1830s. Engels reveals that misleadership is also a problem in these early movements (and still today I would add) due to the low levels of education found amongst the poor and oppressed. He quotes a contemporary witness, Lucian of Samosata (“the Voltaire of classic antiquity”). The Christians “despise all material goods without distinction and own them in common– doctrines which they have accepted in good faith, without demonstration or proof. And when a skillful impostor who knows how to make clever use of circumstances comes to them he can manage to get rich in a short time and laugh up his sleeve over these simpletons.” The Pat Robertsons and Jerry Falwell types have been around for a long time. I am sure readers can add a long list of names. Part 2Engels views on early Christianity were formed from his reading of what he considered “the only scientific basis” for such study, namely the new critical works by German scholars of religion. First were the works of the Tubingen School, including David Strauss (The Life of Jesus). This school has shown that 1) the Gospels are late writings based on now lost original sources from the time of Jesus and his followers; 2) only four of Paul’s letters are by him; 3) all miracles must be left out of account if you want a scientific view; 4) all contradictory presentations of the same events must also be rejected. This school then wants to preserve what it can of the history of early Christianity. By the way, this is essentially what Thomas Jefferson tried to do when he made his own version of the New Testament. A second school was based on the writings of Bruno Bauer. What Bauer did was to show that Christianity would have remained a Jewish sect if it had not, in the years after the death of its founder, mutated by contact with Greco-Roman paganism, into a new religion capable of becoming a world wide force. Bauer showed that Christianity, as we know it, did not come into the Roman world from the outside (“from Judea”) but that it was “that world’s own product.” Christianity owes as much to Zeus as to Yahweh. Engels maintains that The Book of Revelations is the only book in the New Testament that can be properly dated by means of its internal evidence. It can be dated to around 67-68 AD since the famous number 666, as the mark of the beast or the Antichrist, represents the name of the Emperor Nero according to the rules of numerology. Nero was overthrown in 68. This book, Engels says, is the best source of the views of the early Christians since it is much earlier than any of the Gospels, and may actually have been the work the apostle John (which the Gospel and letters bearing his name were not). In this book we will not find any of the views that characterize official Christianity as we have it from the time of the Emperor Constantine to the present day. It is purely a Jewish phenomenon in Revelations. There is no trinity as God has seven spirits (so the Holy Ghost is impossible Engels remarks). Jesus Christ is not God but his son, he is not even equal in status to his father. Nevertheless he has pretty high status, his followers are called his “slaves” by John. Jesus is “an emanation of God, existing from all eternity but subordinate to God” just as the seven spirits are. Moses is more or less “on an equal footing” with Jesus in the eyes of God. There is no mention of the later belief in original sin. John still thought of himself as a Jew, there is no idea at this time of “Christianity” as a new religion. In this period there were many end of times revelations in circulation both in the Semitic and in the Greco-Roman world. They all proclaimed that God was (or the Gods were) pissed off at humanity and had to be appeased by sacrifices. John’s revelation was unique because it proclaimed “by one great voluntary sacrifice of a mediator the sins of all times and all men were atoned for once and for all– in respect of the faithful.” Since all peoples and races could be saved this is what, according to Engels, “enabled Christianity to develop into a universal religion.” [Just as the concept of the workers of the world uniting to break their chains and build a world wide communist future makes Marxism-Leninism a universal philosophy.] In Heaven before the throne of God are 144,000 Jews (12,000 from each tribe). In the second rank of the saved are the non Jewish converts to John’s sect. Engels points out that neither the “dogma nor the morals” of later Christianity are to be found in this earliest of Christian expressions. Some Muslims would presumably not like this Heaven, not only are there no (female) virgins in it, there are no women whatsoever. In fact, the 144,000 Jews have never been “defiled” by contact with women! This is a men’s only club. Engels says that the book shows a spirit of “struggle”, of having to fight against the entire world and a willingness to do so. He says the Christians of today lack that spirit but that it survives in the working class movement. We must remember he was writing this in 1894. There were other sects of Christianity springing up at this time too. John’s sect eventually died out and the Christianity that won out was an amalgam of different groups who finally came together around the Council of Nicaea (325 AD). Those who did not sign on were themselves persecuted out of existence by the new Christian state. We can see the analogy to the early sects of socialists and communists, says Engels. We can also see what happened after the Russian Revolution (Leninists, Stalinists, Trotskyists, Bukharinites, Maoists, etc., etc.). Here in the US today we have the CPUSA, the SWP, Worker’s World, Revolutionary CP, Socialist Party, Sparticists, and etc., etc.). Engels thought that sectarianism was a thing of the past in the Socialist movement because the movement had matured and outgrown it. This, we now know, was a temporary state of affairs at the end of the 19th Century with the consolidation of the German SPD. The wide spread sectarianism of today suggests the worker’s movement is still in its infancy. Engels says this sectarianism is due to the confusion and backwardness of the thinking of the masses and the preponderate role that leaders play due to this backwardness. The Russian masses of 1917 and the Chinese of 1949 were a far different base than the German working class of the 1890s. “This confusion,” Engels writes,”is to be seen in the formation of numerous sects which fight against each other with at least the same zeal as against the common external enemy [China vs USSR, Stalin and Trotsky, Stalin and Tito, Vietnam vs China border war, Albania vs China and USSR. ad nauseam]. So it was with early Christianity, so it was in the beginning of the socialist movement [and still is, peace Engels!], no matter how much that worried the well-meaning worthies who preached unity where no unity was possible.” Finally, for those fans of the 60s sexual revolution, Engels says that many of the sects of early Christianity took the opposite view of John and actually promoted sexual freedom and free love as part of the new dispensation. They lost out. Engels says this sexual liberation was also found in the early socialist movement. He would not, I think, have approved of the excessive prudery of the Soviets. Part 3“Here is wisdom. Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast: for it is the number of a man; and his number IS Six hundred threescore AND six.”– Revelation 13:18 In the last part of his essay Engels explains that the purpose of the Book of Revelations (by John of Patmos) was to communicate its religious vision to the seven churches of Asia Minor and to the larger sect of Jewish Christians that they represented. At this time, circa 69 AD, the entire Mediterranean world much of the of Near East and Western Europe were under the control of the Roman Empire. This was a multicultural empire made of hundreds of tribes, groups, cities and peoples. Within the empire was a vast underclass of workers, freedmen, slaves and peasants whose exploited labor was lived off of by a ruling class of landed aristocrats and merchants. In 69 AD the empire was in essence a military dictatorship controlled by the army and led by the Emperor (from the Latin word for “general”– imperator). At this time there were peoples but no nations in our sense of the word. “Nations became possible,” Engels says, “only through the downfall of Roman world domination.” The effects of which are still being felt in the Middle East and parts of Europe, especially eastern Europe. For the exploited masses of the Empire it was basically impossible to resist the military power of Rome. There were uprisings and slave revolts but they were always put down by the legions. This was the background for what became a great revolutionary movement of the poor and the exploited, a movement that became Christianity. The purpose of the movement was to escape from persecution, enslavement and exploitation. A solution was offered. “But” Engels remarks, “not in this world.” Another feature of the work is that it is a symbolical representation of contemporary first century politics and John thinks that Jesus’s second coming is near at hand. Jesus tells John, “Behold, I come quickly” three times (22:7, 22:12, 22:20). His failure to show up by now doesn’t seem to pose a problem for Christians. As far as the later Christian religion of love is concerned, Engels reports that you won’t find it in Revelation, at least as it regards the enemies of the Christians. There is no cheek turning going on here: it’s all fire and brimstone for the foes of Jesus. Engels says “undiluted revenge is preached.” God is even going to completely blot out Rome from the face of the earth. He changed his mind evidently as it is still a popular tourist destination and the pope has even set up shop there. As was pointed out earlier the God of John is Yahweh, there is no Trinity, it is He, not Christ, who will judge mankind and they will judged according to their works (no justification by faith here, sorry Luther), no doctrine of original sin, no baptism, and no Eucharist or Mass. Almost everyone of these later developments came from Roman and Greek, as well as Egyptian mystery religions. Zoroastrian elements from the Zend – Avesta are also present. These are the idea of Satan and the Devil as an evil force opposed to Yahweh, a great battle at the end of time between good and evil, [the final conflict] and the idea of a second coming. All these ideas were picked up by the Jews during their contact with the Persians before their return after the Babylonian captivity and transmitted to the early Christians. Once we realize all this we can also see why Islam was able to rise to the status of a world religion as well. Those areas of the world that were not the home land of Greco-Roman paganism were open to Islam which spread in areas of Semitic settlement and where Christianity had been imposed by force, so could Islam be. We will give Engels the last word, the Book of Revelation “shows without any dilution what Judaism, strongly influenced by Alexandria, contributed to Christianity. All that comes later is Western , Greco-Roman addition.” About the Author:

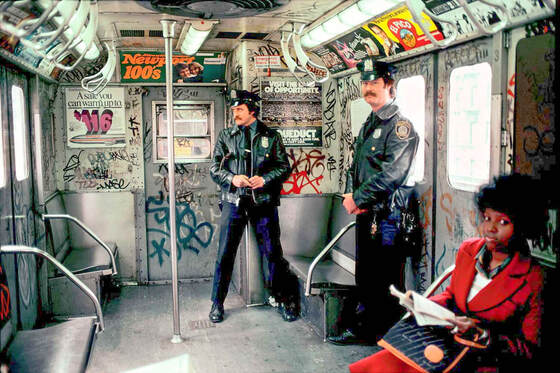

Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Attempts to manipulate and control one’s mind date back as far as 1550 BCE to the Egyptian Book of the Dead. It details occult rituals using “methods of torture and intimidation (to create trauma), the use of potions (drugs), and the casting of spells (hypnotism), ultimately resulting in the total enslavement of the initiate” (Edward). In the beginning of the Cold War era, rumor had it that Stalin was perfecting mind control techniques in the gulags on Chinese and Korean prisoners, but Allen Dulles and Richard Helms wouldn’t let the Soviets go through with this unchallenged. Initially their research into mind control and hypnosis would produce Project Bluebird in 1951, which would be renamed to Project Artichoke later that year to reflect the changes in scope and study- both of which were to be expanded. Artichoke continued to expand, and in 1953 Project MKULTRA would rise from its ashes. MKULTRA was the umbrella project for about 150 subprojects all centering on how the CIA could create their own “Manchurian Candidates” to run operations for them without questioning it, and then having no recollection at all. MI6 in Britain did some work with the CIA, with Dr. Ewen Cameron leading much of their research in Canada. Using witting and unwitting test subjects, MKULTRA studied everything from religious cults, behavioral analysis, sensory deprivation, and chemotherapy radiation, to psychedelic drugs. Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, more commonly known as LSD, or acid, was a drug that was given to subjects as a truth serum. Project MKULTRA was officially shut down by the mid to early 1970s, but attempts at mind control, especially on a national scale, were not. The legacies and effects of MKULTRA are not fully known to us yet, but that which we can speculate is severe. The victims, many unwitting American and Canadian citizens, may never be known to us completely. Many of the victims don’t know that they were associated with the project because their trauma was so intense that the body’s natural reaction was to simply dissociate. The threat of the Soviet Union loomed over Washington like a cloud- ominous and intangible. At the CIA headquarters in Langley it was like a tornado. The Agency’s only mission had become to defend the world from Soviet communism. At the end of WWII there was a race between the British, French, Americans, and Soviets to recruit the intellectual backbone of the Third Reich. This organized, clandestine effort was named Operation Paperclip. Included in this group are those responsible for weaponizing sarin gas and bubonic plague, many of whom would later stand trial for war crimes at Nuremburg. Known as the “Angel of Death” for his work in Auschwitz, “[Josef] Mengele’s research served as a basis for the covert, illegal CIA human research program named MKULTRA” (Edward). Although many in the CIA began their espionage careers in the military or OSS during WWII fighting against the very people they now employed, they saw it as a lesser of two evils scenario. In their minds, they had to make a choice between fascism and communism and using the intellectual leaders of the fascist Third Reich was more appealing than allowing the communist powers a leg up in covert operations (CIA). MKULTRA was the result of a number of projects within different government agencies. Before 1953 the US Navy was studying the effects of brain concussions, specifically centering on memory loss. At some point during that research, they began to wonder if a drug could induce the same amnesia that occurs with a concussion, allowing the potentially successful Manchurian Candidate to have no recollection of their actions. It was at that point that the project was handed off to the CIA because it required human subjects that could not be justified by medical-therapeutic grounds (Drummond). In 1953 the CIA Chief of Special Operations, Richard Helms, wrote a memo to Director Allen Dulles in which he “proposed a program for the ‘covert use of biological and chemical materials’ both for its offensive potential’ to ‘give us thorough knowledge of the enemy’s theoretical potential.’ He recommended shielding the program under extreme secrecy: ‘Even internally in CIA, as few individuals as possible should be aware of our interest in these fields and of the identity of those who are working for us.’ He recommended Sidney Gottlieb to head its operations” (“1953”). Dr. Sidney Gottlieb was the Director of the CIA’s Chemical Division of Technical Service Staff, who specialized in “lethal poisons and creative methods of assassination,” and has been referred to as the CIA’s sorcerer. The author of the report on these memos wrote that “Sidney Gottlieb personified CIA’s immoral universe; a universe where there was nothing, however evil, pointless or even lunatic, that this unaccountable intelligence agency will not engage in, in pursuit of its secret wars. Gottlieb had used his studies on poisons and applied it to the attempted assassinations of world leaders. It’s been reported that Sidney Gottlieb was the inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s character “Dr. Strangelove.” Dulles agreed with Helms on all accounts, and he exempted MKULTRA from “normal CIA financial controls, authorizing Gottlieb to start projects ‘without signing the usual contracts or other written documents’” (“1953”). Much of the research for MKULTRA was done with university professors, frequently using prison inmates and hospital patients as the main subjects. Academics and scholars at the University of Oklahoma, UCLA, University of Wisconsin, Harvard University, University of Illinois, Stanford University, Yale University, Cornell University, and Emory University, to name a few, were involved in MKULTRA research, some wittingly and others unwittingly. Aside from being top individuals in their fields, who would provide excellent research, the CIA had other motivations for using them as well; the idea was that as the project goes on, these individuals could be used as top- secret consultants (Jackman). MKULTRA didn’t begin as an experiment with psychedelic drugs, as its more commonly known for today. In the memo from Richard Helms, we saw that what he described was more centering around chemical and biological weapons, which they had a basis on from the Nazi scientists recruited through Operation Paperclip. However, the goal of MKULTRA shifted from the offensive use of biological and chemical agents to the creation of a Manchurian Candidate. The Manchurian Candidate is a novel published in 1959 by Richard Condon that describes the son of a prominent family in American politics who had been brainwashed into becoming an assassin for a Communist conspiracy. Amid rumors that American soldiers had returned from Korea brainwashed, the CIA didn’t hold back in trying to perfect this as well. Gottlieb, having a specialty in assassination techniques, was the natural architect. The process by which a Manchurian Candidate could be created is known as Monarch Programming. A successful monarch slave will carry out operations, will not question orders, and will not remember their actions. The name comes from a monarch butterfly “who begins life as a worm (representing undeveloped potential), and, after a period of cocooning (programming) is reborn as a beautiful butterfly (the monarch slave)” (Edward). Monarch programming tears down a person’s psyche, so that it can be built back up to have multiple personality disorder, and the different personalities can be triggered at will by the handler. These methods include “electroshock, torture, abuse and mind games in order to force them to dissociate from reality” (Edward). The torture may include confinement in boxes or cages for extended periods of time, near drowning, submersion into ice water or burning chemicals, forced ingestion of offensive body fluids like blood, urine, feces, or flesh, sleep deprivation, stress positions, hanging upside down, sensory deprivation, injection of chemicals such as chemotherapeutic agents, forced ingestion of amphetamines and barbiturates, and being forced to witness the abuse of others. Edward writes, “Due to the severe trauma induced... the mind splits off into alternate personalities from the core... Further conditioning of the victim’s mind is enhanced through hypnotism, double-blind coercion, pleasure-pain reversals, food, water, sleep, and sensory deprivation, along with various drugs which alter certain cerebral functions.” Once the victim dissociates and a split in personality occurs, the programmer can create alter personas to be triggered with a phrase or symbol. An official Monarch Program within the CIA has never been proven to have existed, however when CIA Director William Colby was asked, “he replied angrily and ambiguously, ‘We stopped that between the late 1960s and the early 1970s’” (Edward). The CIA’s Monarch-like experiments were not held in the United States, and were performed by Dr. Ewen Cameron, a British psychiatrist, in Canada. Cameron had been studying what he considered psychotherapy, which involved a three-step process on mostly involuntary hospitalized women. The first step, mental depatterning, put subjects into a drug-induced coma for prolonged periods of time- some up to eighty-six days. The second step involved three high-voltage electroshock treatments every day, continuing the electroshock until the subject stops convulsing. The final step puts victims into isolated confinement, being kept on LSD while under food, water, sleep, and sensory deprivation. During this third step the victim would be subjected to what Cameron called psychic driving, “by use of a football helmet clamped to the head with taped messages played for hours non-stop" (“1950s”). This psychic driving could go on for weeks. After their “treatment,” most of his patients after were reduced to a state of infancy and lost almost all basic cognitive and motor functions. In the case of Gail Kastner, “The shock treatment turned the then 19-year-old honours student into a woman who sucked her thumb, talked like a baby, demanded to be fed from a bottle and urinated on the floor” (“1950s”). Cameron had been doing research like this before he was contracted by the CIA, but it was an opportunity that neither of them could refuse. For the CIA, they had found someone who was willing to perform electroshock experiments, drug tests, and deprivation exercises on unwitting subjects. For Cameron, he found someone to fund his sadistic research. Cameron gave his plans, and the Agency funded them. MKULTRA experimented with the same techniques on American soil. However, the CIA did more experiments with drugs than the basic monarch programming. The CIA didn’t just use LSD, in fact one of their methods to force sleep deprivation was to give subjects a constant cocktail of amphetamines and barbiturates- uppers and downers. While awake, the victims would be given barbiturates which would make them calm and sleepy- at which point they’d be given amphetamines to make sleep near impossible. The victims of this could be anyone- witting volunteers, unwitting victims, pregnant women, prison inmates, hospital patients, rehab patients, or even members of the US military. CIA experiments with drugs were very holistic, almost all demographics were targeted to give an encompassing view of how people respond to physical trauma and drugs. One experiment studying the effects of prolonged exposure to LSD at the US Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, then called the Federal Addiction Research Center, had heroin addicts be put on LSD for 77 days straight under the supervision of Dr. Harris Isbell, a CIA contracted psychiatrist. The subjects were told they would be doing drug experiments, nothing more specific, and were promised free heroin at the end of the tests as a reward for their participation (Mernit and Morowitz). Another experiment looked to see LSD’s effect on soldiers. The US Army had been conducting tests in conjunction with the CIA to see if LSD could be used as a drug to incapacitate enemies, but not kill them. Using witting volunteers, the Army had soldiers run basic drills on command from their drill sergeant, which they performed like clockwork. Then, the soldiers were given LSD, and after a certain amount of time (which allowed the drug to kick in) they were ordered to do the same basic drills. The results were confounding for the observing scientists. Soldiers became giggly, fell out of line, performed slower than normal, and had a hard time doing simple tasks like jumping over a wooden obstacle (Mernit and Morowitz). The CIA’s LSD experiments expanded past labs and controlled tests on witting volunteers, however. One subproject of MKULTRA, Operation Midnight Climax, involved the CIA running brothels in San Francisco and New York, hiring prostitutes to pick up men at bars, bring them back, and dose their cocktails with LSD. Two-way mirrors were put into the bedrooms, behind which a CIA officer would be observing the men's behavior. Aside from simply observing the johns, the CIA also was observing the women. They wanted to look at how the women responded to being given clandestine missions, and whether they could be turned into agents with split personalities, Manchurian candidates. The man Sidney Gottlieb put in charge of overseeing Midnight Climax was Col. George White. White had earned the rank of lieutenant colonel during his time in the OSS, the precursor to the CIA, during WWII. Upon White’s death in 1975, his widow left his diaries and papers to a junior college outside of San Francisco, from which we now have dates, names, and thoughts behind Midnight Climax which had yet to be uncovered. White wrote that he had met with Sidney Gottlieb and his deputy, Dr. Robert Lashbrook. Gottlieb recruited him to be a consultant, and a year later he was on CIA payroll. White was officially put in as the regional head of the Bureau of Narcotics, and unofficially oversaw Midnight Climax. In the safehouse that became White’s residence, he was known to keep pitchers of chilled martinis in the refrigerator and had photos of women being tortured and whipped, implying that he may have taken pleasure from his new position. White was so intrigued with his research that he himself used LSD under the supervision of psychiatrists, psychologists, and pharmacologists. White wrote, “So far as I was concerned, ‘clear thinking’ was nonexistent while under the influence of any of these drugs. I did feel at times that I was having a ‘mind-expanding experience,’ but this vanished like a dream immediately after the session” (“Diaries...”). The supervisors of Midnight Climax wanted to step up the experiment to a more realistic scenario. If the goal was to use LSD as a truth serum for foreign diplomats, foreign agents, or anyone with information to share, they needed to test it as such on people who had secrets. The CIA sought out drug dealers to be used, drugged, and questioned to simulate a real-life interrogation. Some experiments had to do with contaminating entire cities with LSD, as was tested in New York and France by CIA research scientist Dr. Frank Olson and Lt. Col. George White. Dr. Olson specialized in aerosol chemical delivery, which subsequently was how LSD was released into the New York subway system in 1952 by White- among unwitting American citizens as subjects. The evidence of this experiment is spotty, however it was documented in White’s personal diary and confirmed by a colleague of Dr. Olson’s, Dr. Henry Eigelsbach. However, the New York experiment pales in comparison to an alleged CIA experiment in the French town of Pont St. Esprit. A New York Post article reports, “Over a two-day period, some 250 residents sought hospital care after hallucinating for no apparent reason. Thirty-two patients were hauled off to mental asylums. Four died. Mercury poisoning or ergot, a fungus of rye bread, was cited as the cause of the symptoms. Ergot is also one of the central ingredients of LSD. And curiously enough, Olson and his government pals were in France when the craziness erupted” (Messing). It’s unknown whether the French government was consulted hitherto. For much of the duration of MKULTRA, other government agencies were involved to make the process go by without complication. The Department of Agriculture was helpful in speeding up the process of bringing “various botanicals” into the country for Project Artichoke and shows the FDA cooperating to allow the CIA to use laboratories and testing facilities- making these agencies complicit, whether they knew the CIA’s intentions or not (Jacobs). In his personal writings, Lt. Col. White discussed that although the Bureau of Narcotics was involved, its chief would “disclaim any knowledge of it” if he were ever to be asked (Drummond). The FDA was perhaps the agency most closely linked to MKULTRA. In 1962, a regulation was passed through Congress stating that any and all testing with LSD was to be done with special permission from the FDA, however there were loopholes for the CIA and Department of Defense in which the FDA could grant “selective exemptions.” If any research was classified for reasons of national security, the FDA ignored it, stating that “those seeking to develop hallucinogens as weapons were somehow more ‘sensitive to their scientific integrity and moral and ethical responsibilities’ than independent researchers dedicated to exploring the therapeutic potential of LSD” (Martin and Shlain). The FDA also provided personnel with security clearance to act as “consultants for chemical warfare projects” (Martin and Shlain). When LSD was declared illegal in the late 1960s, MKULTRA began to quietly shut down. Conveniently, in the early 1970s Director Richard Helms and Sidney Gottlieb, one of the masterminds behind MKULTRA ordered all relevant paperwork be destroyed (Boylan). Gottlieb said that [MKULTRA and MKSEARCH] had been a waste of time, citing certain “scientific and operational flaws” ("June 1972”). The techniques that they were using to try to control human behavior proved to be too unpredictable, which, ironically enough, was the same conclusion that Nazi scientists had reached at Dachau in the 40s ("June 1972”). MKULTRA officially ended without anything going too public. That was, however, until Seymour Hersh, an investigative journalist, published an article in the New York Times just a few months after the Watergate scandal announcing that the CIA was spying on American citizens. This forced President Ford’s hand to create a commission led by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller into unlawful CIA activities. Only two pages of the entire commission were about MKULTRA, because the report downplayed the scope of the project. It did, however, mention the story of a CIA employee who jumped from his hotel window in New York City after having been dosed with LSD a few days earlier. The family quickly recognized the story as being about Dr. Frank Olson, whose family was told he committed suicide in 1953. Within ten days, the Olson family had made public accusations that the CIA had a role in Dr. Olson’s death, and were in the Oval Office receiving a formal apology from President Ford and $750,000 as compensation. The implicit reasoning for the money was to appease the family so they would drop their lawsuit against the US government. Later in 1974, Seymour Hersh exposed MKULTRA in an article he published which eventually led to the special hearings of the Church Committee (Boylan). The Church Committee is what provided us with testimonies about MKULTRA and gives us most of the information we have now. Although Helms and Gottlieb ordered the paperwork destroyed, the committee found a money trail with corresponding documents. More of MKULTRA was exposed by John Marks, who got about 16,000 pages of CIA documents through the Freedom of Information Act. There were several smaller commissions, including the Pike Committee Investigation. Although many of them, including Pike, were met with hostility by the CIA and White House. The opening line of the Pike report reads, “If the Committee’s recent experience is any test, intelligence agencies that are to be controlled by Congressional lawmaking are, today, beyond the lawmaker’s scrutiny” (“February 1975”). Citations Boylan, Dan. “Acid Flashback: CIA's Mind-Control Experiment Reverberates 40 Years after Hearings.” The Washington Times, The Washington Times, 30 Aug. 2017, www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/aug/30/cias-mk-ultra-lsd-mind -control-experiment-has-ling/. “CIA Had Nazi Doctors Test LSD On Captured Soviet Spies, Book Says.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 13 Feb. 2014, www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/02/13/operation-paperclip_n_4781137.html. Cohen, Zachary. “CIA Explored Using Potential Truth Serum Drug for Post 9/11 Interrogations.” CNN, Cable News Network, 13 Nov. 2018, www.cnn.com/2018/11/13/politics/cia-documents-truth-serum-drug -interrogations/index.html. Drummond, Katie. “Chemical Concussions and Secret LSD: Pentagon Details Cold War Mind -Control Tests.” Wired, Conde Nast, 14 Jan. 2018, www.wired.com/2010/05/chemical -concussions-and-secret-lsd-military-releases-cold-war-mind-control-report/. Edward, Sebastian. “MK-Ultra Project,Monarch and Julian Assange – Sebastian Edward – Medium.” Medium.com, Medium, 20 Jan. 2015, medium.com/@sebastianedward/mk -ultra-project-monarch-and-julian-assange-ad2aa42ba1a4. “February 1975: President Ford Appointed a Commission Headed by Nelson Rockefeller.” McCann 13 AHRP, 26 Mar. 2015, ahrp.org/feb-1975-president-ford-appointed-a-commission -headed-by-nelson-rockefeller/. Finger, Stan. Homeland Security Plans Inert Chemical Tests near Kansas Border. The Wichita Eagle, 9 Nov. 2017, www.kansas.com/news/local/article183818896.html. “Harmless Gas Released into New York Subway to Prep for Biological Attack.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 9 May 2016, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/may/09/new-york-city-subway-harmless-gas -released-biological—attack-study-jessica-now. Hatmaker, Taylor. “DARPA Awards $65 Million to Develop the Perfect, Tiny Two-Way Brain -Computer Interface.” TechCrunch, TechCrunch, 10 July 2017, techcrunch.com/2017/07/10/darpa-nesd-grants-paradromics/. Jackman, Tom. “The Assassination of Bobby Kennedy: Was Sirhan Sirhan Hypnotized to Be the Fall Guy?” The Washington Post, WP Company, 4 June 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/news/true-crime/wp/2018/06/04/the-assassination -of-bobby-kennedy-was-sirhan-sirhan-hypnotized-to-be-the-fall-guy/ ?utm_term=.4449af741e24. Jacobs, John. “CIA Papers Detail Secret Experiments on Behavior Control.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 21 July 1977, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1977/07/21/cia-papers-detail McCann 14 -secret-experiments-on-behavior-control/90524b32-2527-413b-9673-f57be3ce7800/ ?noredirect=on&utm_term=.686ff4748698 Jacobs, John. “The Diaries Of a CIA Operative.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 5 Sept. 1977, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1977/09/05/the-diaries-of-a -cia-operative/65b08a3e-c95a-434e-b1c6-c05f726a3a6f/ ?noredirect=on&utm_term=.99166637bc9e. “June 1972: Project MK-ULTRA and MK-SEARCH Were Terminated by Sidney Gottlieb.” Alliance for Human Research Protection, -http://ahrp.org/june-1972-project-mk-ultra -and-mk-search-were-terminated-by-sidney-gottlieb/. Lee, Martin, and Bruce Shlain. “An Excerpt from Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD The CIA, the Sixties and Beyond.” Acid Dreams, Grove Press, 1985, www.levity.com/aciddreams/samples/ciafda.html. Mernit, John, and Morowitz, Noah. CIA Secret Experiments Documentary. National Geographic Television, National Geographic, 26 Dec. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch ?v=7Afjf2ZgGZE. Messing, Philip. “Did the CIA Test LSD in the New York City Subway System?” New York Post, New York Post, 14 Mar. 2010, nypost.com/2010/03/14/did-the-cia-test-lsd-in-the -new -york-city-subway-system/. Odeshoo, Jason R. “Truth or Dare?: Terrorism and ‘Truth Serum’ in the Post-9/11 World.” Stanford Law Review, vol. 57, no. 1, 2004, pp. 209–255. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40040204. Rodriguez, Nicole. “Homeland Security Chemical Attack Tests Could Turn People into Lab Rats, Residents Say.” Newsweek, 12 Dec. 2017, www.newsweek.com/chemical -warfare-drills-homeland-security-turn-people-lab-rats-residents-fear-745697. Ross, Colin. “The C.I.A. Mind Control Doctors.” CCHR International, 26 July 2013, www.cchrint.org/2009/09/03/cia-mind-control-doctors/. Wolverton, Joe. “Pentagon Dumps $65 Million Into Mind-Control Project.” The New American, www.thenewamerican.com/tech/item/26528-pentagon-dumps-65-million -into-mind-control-project. “1950s–1960s: Dr. Ewen Cameron Destroyed Minds at Allan Memorial Hospital in Montreal.” AHRP, 26 Mar. 2015, ahrp.org/1950s-1960s-dr-ewen-cameron-destroyed-minds-at -allan-memorial-hospital-in-montreal/. “*1953: MK-ULTRA Was Hatched by Allen Dulles and Richard Helms.” AHRP, 26 Mar. 2015, ahrp.org/1953-mk-ultra-was-hatched-by-allen-dulles-and-richard-helms/. “1974: Seymour Hersh Exposes HUGE CIA Spying on Americans.” AHRP, 26 Mar. 2015, ahrp.org/1974-seymour-hersh-exposes-huge-cia-spying-on-americans/. About the Author:

Joseph Senecal is a student completing undergraduate research in international studies and political science at Flagler College in St. Augustine, Florida. McCann is interested in structuralism, post-structuralism, ideology, revolutionary history, and translation. Particularly inspired by French structuralist and existentialist writers of the 1960s, McCann hopes to translate works that have yet to be put in English for an American audience. Applying to doctoral programs in philosophy and political science, McCann hopes to continue his education in Marxian thought. In his personal life, he works as a cook, enjoys blues rock, and has an adored cat named Carlos Santana. It is generally accepted by most on the ‘left’ that capitalism required the black slave for capital to be “kick-started”,[1] and consequently, that the similarities in the lives of the early black slave and the white indentured servant required the creation of racial differentiation (hierarchical and racist in nature) to prevent Bacon’s Rebellion style class solidarity across racial lines from reoccurring. The capitalist class in the US has been historically successful in creating an atmosphere within the circles of radical labor that excludes solidarity with black liberation and feminist struggles. Yet, the black community historically has been at the forefront of the struggle for socialism in the US. Taking into consideration the history of dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, radical labor in the US has had towards black struggles for liberation, how could it be that the black community has stood in a vanguard position in the struggle for an emancipation that would include those whom they have been excluded by? This paper will look at two occasions in which we can see the exclusion of identity struggles from labor struggles, and answer the riddle of how white labor has been able to identify more with capitalist of their own race than with their fellow nonwhite worker. In connection to this, we will be examining three different perspectives concerning the relationship of the black community’s receptivity and active role in the struggle for socialism and the emancipation of labor. A perfect example of this previously mentioned exclusion of identity from labor can be seen in Jacksonian radical democrats like Orestes Brownson, who although representing a radical emancipatory thought in relation to labor, failed to see how the abolitionist movement should have been included into the cause of the northern workers. Thus, his positions was (before falling into conservatism), that “we can legitimate our own right to freedom only by arguments which prove also the negro’s right to be free”.[2] The question is the negro’s right to be free when? Although he included blacks into the general emancipatory process, he was staunchly against abolitionist as “impractical and out of step with the times”,[3] and eventually urged northern labor to side with the southern plantation owners to counter the force of the northern industrial capitalist. What we see here with Brownson is a dismissal for the abolitionist struggle against black chattel slavery, unless it takes a secondary role to white labor’s struggle for the abolition of wage slavery. Brownson’s central flaw here is his assumption that you can free one while maintaining the other in chains, whereas the reality is that “labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded”[4] In the generation of American radicals that came after Brownson we see a similar dynamic between the 48’ers[5] of the first section of the International and the utopian/feminist radicals of sections nine and twelve. This split takes place between Sorge and the German Marxist and the followers of the ‘radical’ Stephen Andrews and the spiritualist free-love feminist Victoria Woodhull. As Herreshoff states, in relation to the feminist movement of the time, “the Marxists were talking to the feminist the way Brownson had talked to the abolitionist before the Civil War.”[6] By this what is meant is that the struggle for women’s political emancipation, was treated as a sideline issue, that should be dealt with – or automatically solved – only after labor’s emancipation. Now, it could very well be argued that the positions taken by Sorge and some of the other Marxist 48’ers was not ‘Marxist’ at all. Marx and Engels were staunch abolitionist, close followers (and writers) of the Civil War, and even pressured Lincoln greatly towards taking up the cause of emancipation; this puts them in a direct opposition to the positions taken by the northern labor radicals like Brownson[7]. Engels also pronounced himself fully in favor of women’s suffrage as essential in the struggle for socialism[8]. The expansion of this argument cannot be taken up here though. The point is that racial and sexual contradictions within the working masses have played an essential function in maintaining the capitalist structures of power. While workers identify – or are coerced into identifying – workers of other races, ethnicities, or sexes as their enemy, their real enemy – their boss – is either ignored or positively identified with. Thus, white workers can blame their wage cuts/stagnations on the undocumented immigrant. Although he does play a function in maintaining wages low, the one who sets the terms for the function the immigrant is coerced into playing is the capitalist, not the immigrant. There are countless analogies to describe this relation, my favorite perhaps is the one of the cookies. In a table you have 100 cookies, on one side of the table you have the capitalist (usually caricatured as a heavy-set fellow) with 99 cookies to eat for himself. On the other side you have a dirtied white face worker, a dirtied brown face immigrant worker, and finally, the last cookie. The capitalist leans to the white worker and tells him, “be careful, the immigrant will take your cookie”. Here we have the general function of racial division, the motto which is “have the white worker base his identification not in the dirt on his face, but in the mythical face laying under the dirt”. This mythical face under the dirt is the symbolic link of the white worker and the white capitalist. The link of commonality is based on the illusion of the undirtied faced white worker. The dirt, of course, symbolizes the everyday conditions of his toiling existence. Even though the white worker’s everydayness is infinitely more like the immigrant’s (immigrant here is replaceable with black/women/etc.), he is coerced into consenting his identification with whom he has in common no more than one does with a bloodsucking mosquito on a hot summer’s day. Regardless of the dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, of radical labor’s relation to other identity struggles, the black community has been in the forefront of the struggle for socialism in America. Not only have elements of the black community consistently served as the revolutionary vanguard, but the community itself has historically expressed a receptivity of socialism that is unmatched by their white working-class counterparts. There have been a few interesting ways of explaining the phenomenon of the black community’s receptivity of socialist ideas. Edward Wilmont Blyden, sometimes called the father of Pan-Africanism, argued in his text African Life and Customs that the African community is historically communistic. Thus, there is something communistic within the ethos of the black community, that even though it has been generationally separated from its origins, maintains itself in the black experience. He states that the African community produced to satisfy the “needs of life”, held the “land and the water [as] accessible to all. Nobody is in want of either, for work, for food, or for clothing.” The African community had a “communistic or cooperative” social life, where “all work for each, and each work for all.”[9] The argument that a community’s spirit or ethos plays an essential role in its ability to be receptive to socialism is one that is also being analyzed with respect to the “primitive communism” of indigenous communities in South America. Most famously this is seen in Mariategui, who states: “In Indian villages where families are grouped together that have lost the bonds of their ancestral heritage and community work, hardy and stubborn habits of cooperation and solidarity still survive that are the empirical expression of a communist spirit. The “community” is the instrument of this spirit. When expropriations and redistribution seem about to liquidate the “community,” indigenous socialism always finds a way to reject, resist, or evade this incursion.”[10] These arguments have been recently found by Latin American Marxist scholars like Néstor Kohan, Álvaro Garcia Linera, and Enrique Dussel, to have already been present in Marx. From the readings of Marx’s annotations of the anthropological texts of his time (specifically Kovalevsky’s), they argue that Marx began to see the revolutionary potential of the “communards” in their communistic sprit. This was a spirit that staunchly rejected capitalist individualism, leading him to believe that its clash with the expansive nature of capital, if victorious, could be an even quicker path to socialism than a proletarian revolution. Not only would the indigenous community serve as an ally of the proletariat as revolutionary agent, but the communistic spirited community is itself a revolutionary agent too.[11][12] Another way of explaining the phenomenon of a historically white radical labor movement (at least until the founding of CPUSA in 1919), and a historically radical black community[13], is through reference to an interview Angela Davis does from prison when asked a similar question. In this 1972 interview Angela mentions that the black community does not have the “hang ups” the majority of the white community has when they hear the word ‘communism’. She goes on to describe an encounter with a black man who tells her that although he does not know what communism is, “there must be something good about it because otherwise the man wouldn’t be coming down on you so hard.”[14] What we have here is a sort of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. The acceptance of communism is because of the militant rejection my oppressor has towards it. Although it might seem as a ‘simplistic’ conclusion, I assure there is a profound rationality behind it. The rationality is this “if the alternative is not different enough to scare my oppressors shitless, it is not an alternative where my conditions as oppressed will change much.” This logic, simplistic as it might seem, is one the current ‘socialist’ movement in the US is in dire need of re-examining. If the alternatives one is proposing does not bring fright upon those whose heels your necks are under, then what one is proposing is no qualitative alternative at all; rather, it is merely a request to play within the parameters the ruling class gives you. The relationship of who is setting the parameters is not changed by the mere expansion of them. Both of these ways of examining the question concerning the relationship of the black community and its acceptance of socialist ideas I believe hold quite a bit of truth to them. Regardless, I think there is one more way to answer this question. The difference is that in this new way of answering the question, we are threatened with finding the possibility of the question itself being antiquated. The thesis I think is worth examining relates to this previous “mythical link” the white worker can establish with the white capitalist. Unlike the white worker, the black worker has not – at least historically – had the ability to identify with a black capitalist from the reflective position of his ‘undirtied’ face. This is given to the fact that the capitalist class, or even broader, the class of elites or the top 1%, has been almost homogeneously white. Thus, whereas the white worker could be manipulated into identifying with the white capitalist, the white homogeneity of the capitalist class did not have the ripe conditions for working class black folks to be manipulated in the same manner. The question we must ask ourselves now is: in a world of a socially ‘progressive’ bourgeois class, like the one we have today, can this ‘mythic-link’ come into a position of possibly becoming a possibility? With the efforts of racial (and sexual) diversification of the top 1%, can this change the relationship of the black community to radical politics? If we accept the thesis that the link of the black community to radical politics has been a result of not being able to – unlike the white worker – have any identity commonality with their exploiter, then, can we say that in a world of a diversified bourgeois class, the radical ethos of the black community is under threat? Is the black working mass and poor going to fall susceptible to the identity loophole capitalism creates for coercing workers into consenting against their own interest? Or will its historical radical ethos be able to challenge it, and see the black bourgeois as much of an enemy as the white bourgeois? Under a diversified bourgeois class, will Booker T. Washington style black capitalism become hegemonic in the black community? Or will the spirit still be that of Fred Hampton’s famous dictum from his Political Prisoner speech “You don’t fight fire with fire. You fight fire with water. We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity. We’re not gonna fight capitalism with black capitalism We’re gonna fight capitalism with socialism.”? I am unsure, but I think perhaps a totally disjunction-al way of thinking about it is incorrect; as in, the disjunction will not be one the totality of the community is forced to homogeneously choose, but one which fractures the community itself without leaving any side’s perspective hegemonized. Regardless, I think it is up to those who represent the cause of the white and non-white working mass and poor, to go these spaces and assure that masses begin to identify based on class lines (‘class’ not restrictive to the industrial proletariat, but expanded to the totality of the working masses, and beyond that to the lumpen elements whose systemic exclusion, excludes them as well from being exploited subjects of the system). Only in this ‘class’ identity approach can we achieve the unity necessary to solve not just the antagonisms of class that capitalism develops and continuously exacerbates, but also those of race, sex, and climate. This does not mean, like it meant for the 19th century labor radicals, that we exclude non-class struggles to a peripherical position where we give them importance only after the socialist revolution has triumphed. Rather, our commonality of interests in transcending the present society forces us to examine how we can work together, and in doing so, begin to acknowledge and work on the overcoming of our own contradictions with each other. Citations. [1]III, F. B. (2003). The Prison Slave as Hegemony's (Silent) Scandel. In Afro-Pessimism An Introduction (pp. 72). [2] Brownson, O. A. “Slavery-Abolitionism.” Boston Quarterly Review, I (1838), (pp. 240). [3] Herreshoff, D. American Disciples of Marx (Wayne State University Press, 1967), (pp. 39). [4] Marx, K. (1967). Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production (Vol. 1). (F. Engels, Ed.) International Publishers. (pp. 301) [5] “48’ers” refers to the Germans that came after the attempted revolution of 1848 (the one the Communist Manifesto was written for). Having to face persecution, many fled to the US. [6] Ibid. (pp. 82). [7] For more see: Marx, K. & Engels, F. The Civil War in the United States (International Publishers, 2016) [8] For more see: Engels, F. The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (International Publishers, 1975) [9] Blyden, E. W. African Life and Customs (Black Classic Press, 1994) (pp. 10-11) [10] Mariategui, J. C. Seven Essays of Interpretation of Peruvian Reality (1928), (pp. 68) [11] Linera, A. G. (2015) Cuaderno Kovalevsky. In Karl Marx: Escritos Sobre la Comunidad Ancestral [12] This is itself a message that strikes at the heart of the dogmatism of certain Marxist circles. Circles that religiously follow the early unilateral theory of history Marx’s begins proposing in The German Ideology, a view that was used to argue the revolutionary futility of these communities, and the need to ‘proletarianize’ them. This does not mean we throw out Marx’s discovery of the materialist theory of history upon which the unilateral theory of history arises; but rather, that we treat it in a truly materialist manner (as the later Marx does) and realize the ‘five steps’ to communism is materially specific to the studies Marx had done with relation to the European context. With relation to other contexts, new studies must be made through the same materialist methodology. [13] This is not to be taken as a statement of the homogenous radicalism of the black community in America. The influence of Booker T Washington style of black capitalist ideology does historically have a certain influence in the black community. But, when considered in proportion to the white population, the acceptance of socialism – and its vanguard role in struggles – has been much greater in the black community. [14] Marxist, Afro. (2017, June 11) Angela Davis - Why I am a Communist (1972 Interview) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGQCzP-dBvg About the Author:

My name is Carlos and I am a Cuban-American Marxist. I graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Loras College and am currently a graduate student and Teachers Assistant in Philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. My area of specialization is Marxist Philosophy. My current research interest is in the history of American radical thought, and examining how philosophy can play a revolutionary role . I also run the philosophy YouTube channel Tu Esquina Filosofica and organized for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Cooperatives, enterprises where workers are the owners of their workplace, have always held an awkward place in the socialist movement. Proponents, such as Robert Owen, saw worker cooperatives as socialism in practice. Other socialists, such as Karl Marx criticized cooperative projects for being “utopian” in the sense that cooperative advocates sought to build a socialist society without first dismantling the existing order. Rosa Luxemburg’s critique of the cooperative movement best exemplified the thought among many Marxists, “The workers forming a co-operative in the field of production are thus faced with the contradictory necessity of governing themselves with the utmost absolutism. They are obliged to take toward themselves the role of capitalist entrepreneur—a contradiction that accounts for the usual failure of production co-operatives which either become pure capitalist enterprises or, if the workers’ interests continue to predominate, end by dissolving.” Mark and Luxembourg were not wrong. Take the Mondragon Corporation, which is the largest worker cooperative in the world, employing 81,507 people and generating 12 billion euros in revenue. But market pressures to maximize profits over the broader interests of the community have eroded Mondragon to adopt exploitative practices typical of a corporation. Today, only a minority of Mondragon’s workers are owners and the cooperative is infamous for suppressing labor unions in its foreign subsidiaries. As cooperatives became more profitable, the worker-owners started to lose their sense of solidarity with their fellow workers as their self-image takes on the contours of a small business owner. Are cooperatives fated to end up like Mondragon? A growing group of organizers and academics are firmly saying “NO.” Learning from the accomplishments and failures by previous socialist experiments, these activists are confronting the assumptions that cooperatives cannot dismantle the existing institutions of oppression, are anti-political, and suppress class consciousness. But before that, let’s talk about the other and larger socialist movement that has dominated much of the 20th century. The Social Democratic CenturyMost leftists agreed with Luxembourg and instead opted to join the social democratic movement. Unlike cooperatives, social democracy was perceived as political and militant. Social democrats believed the best path to abolish capitalism was by expanding the state bureaucracy through political parties and trade unions. The legacy of the New Deal era, a period of high union density and massive expansion of government programs, seemed to have validated those beliefs. But what followed social democracy wasn’t socialism, what followed was neoliberalism, also known as a 40-year bipartisan effort to undo every aspect of the New Deal from slashing taxes for the rich, weaponizing racist dog whistles as an excuse to gut welfare, and pass massive layoffs in the industrial heartland. In their book “Bigger than Bernie”, Jacobin contributors Meagan Day and Micah Uetricht argue that the revived socialist movement’s main priority should be to finish the New Deal. Day and Uectricht’s call to undo the last 40 years is best reflected in the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) national platform, which currently consists of building a rank and file labor movement, electing democratic socialists to office, and passing Medicare for All and a Green New Deal. Though Day and Uetricht acknowledge it’s simply not enough to rebuild the welfare state. As numerous historians have pointed out, a major cause for the downfall of the social democratic era was union bureaucrat’s suppression of militant labor organizers during the 2nd Red Scare. Day and Uetricht advocate for a supposedly revised version they call “class struggle social democracy.” The basic idea is that socialists should elect social democratic politicians and agitate for a militant labor movement at the same time. The assumption is that a militant labor movement can act as a check on social democracy’s tendency “to limit the scope and substance of the reforms which it has itself proposed and implemented, in an endeavor to pacify and accommodate capitalist forces." But organizing a militant labor movement isn’t new, it was actually the main strategy for social democrats in the 20th century. While the CIO leadership did try to contain the more radical sections of the labor movement, the labor federation still relied on militant actions to force concessions. In 1936, the United Auto Workers organized the famous Flint Sitdown Strike, even though the Wagner Act already created the National Labor Relations Court to mediate labor disputes the year before. Union bureaucrats containing more militant activists can only explain part of the decline of social democracy, a greater factor was the expansion of the professional-managerial class. A large reason why so many working-class households left the union hall for the cubicle was the level of education and experience many white-collar jobs required allowed those workers to negotiate higher wages without the need for a union. A New York Times article on Tom Harkin’s failed 1992 presidential run sums up how devastating the professionalization of America had an effect on the left, "The audience for Harkin's message is literally and figuratively dying," says Mike McCurry, the senior communications adviser to Kerrey. "It's just not appealing to the baby boomers, the geodemographic bulge that accounted for the Republican ascendancy of the 80's and that might signal a new Democratic resurgence in the 90's. These are people with virtually no party affiliations. The imagery of Roosevelt's New Deal simply does not resonate with them." A revived social democratic movement will only recreate this cycle of a generous welfare state expanding a professional middle class that would push for reforms that will then shrink the middle class and so on and so forth. But can the cooperative, that utopian experiment, provide a new path towards socialism? Cooperative activists correctly point out that worker-ownership reverses the dynamics between management and labor and thereby provide a much more radical transformation than expanding government programs and trade union density. Three case studies, one historical and two that are ongoing, provide evidence that cooperatives do not inherently have to cave to market forces but can act as a catalyst for social movements, and most importantly, by allowing people to experience a life where workers can own the means of production, they can counter the pressures to assimilate back to capitalism. The Populist Movement