|

Originally published: Morning Star Online on July 5, 2024 by Roger McKenzie (more by Morning Star Online) | (Posted Jul 10, 2024) THE Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang is at the geographical centre of Eurasia. The region borders eight other countries which makes it a vital part of Chinese plans for the greater integration of Eurasia and the westward opening up of this nation of 1.4 billion people. The Comprehensive Bonded Zone in the city of Kashi is central to co-ordinating the booming trade links that China has established with its immediate neighbours. Xinjiang, one of the largest regions in China, is a gateway to Russia, India, Pakistan, Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Afghanistan. It occupies around 643,000 square miles of China–a space larger than six Britains. Its sparse population of approximately 25 million is mainly Muslim and made up of around 65 different ethnic groups including Chinese Han, Uighurs, Kazakhs and Hui, among others. I lost count of the number of mosques that I saw during my recent trip. I visited a thriving Islamic Centre in the city of Urumqi–which has received millions in funding from the Chinese government for its development to teach its around 1,000 students. I had the honour of sitting in the mosque’s main hall attached to the centre alongside the imam and hearing him talk about the support the centre had received from the government. I also visited the magnificent and extremely busy Id Kah Mosque in the city of Kashi. Both times the imams took the time from their busy schedules to speak about how grateful they and worshippers at the mosque are for the support provided by the government. They told me about how the right to worship any religion is considered a private matter in China and protected in law. That’s why it provides funds to a wide range of religious bodies representing Muslims, Buddhists and Christians among others. None of this is recognised in the West. Instead tall tales are told about supposed widespread religious persecution. In particular Western politicians and their stenographers in the corporate media continue to spin untruths about the treatment of religious minorities. To be crystal clear: at no time did I witness any attempt to block anyone from being able to worship according to the Islamic faith or, for that matter, any other religion. I heard no criticism of the government over religious persecution from senior religious figures or anyone else I met during my visit. I was never stopped from speaking with anyone in any of the large crowds of people that I found myself in across the region. Having made the effort to actually visit five cities in 10 days in the region rather than pontificate from thousands of miles away, I can honestly say that for a country that supposedly routinely oppresses ethnic minorities China seems to spend an inordinate amount of time celebrating them. By that, I don’t mean the half-arsed patronising so-called celebration of diversity that now appears customary across Britain. Leading figures in Britain trip over themselves to take a knee and say how much black lives matter to them but continue to do nothing about racism in their organisations. It doesn’t look to me like a Black History Month-type gig where a big show is made for a short tokenistic period and then ignored for the rest of the time. Talking up the richness of the region’s cultural diversity wasn’t just an isolated thing in Xinjiang–it was everywhere. Celebrations of the Islamic culture were everywhere for anyone to see. I can already hear some saying that either I wasn’t looking hard enough or I was having the wool pulled over my eyes. I did look hard and I don’t believe an elaborate hoax was being played on me. I spoke with lots of people in private with no restrictions placed on me whatsoever. In fact, my dreadlocks, and I dare say, the colour of my skin, meant I was a target of curiosity, especially among the young, many of who wanted to come and chat and have a photo taken with me. That was frankly the most uncomfortable thing about the trip! What I saw was lots of people going about their business in much the same way as I have seen people trying to do in many parts of the world. I met many Communist Party officials who were questioned over the allegations made against them and their country. All of them said the only way to counter the propaganda war being waged against them was for people to come and see for themselves. They told me how hard they were working to open up the region to more tourism so that people could experience this beautiful area but also so more people could bear witness to the truth about them. So why is this propaganda war being waged against China in general and in particular against Xinjiang? The geographical position of the region provides the answer. As the centre of the Silk Road renaissance, the region will be the focal point of Chinese trade and its economic heartbeat. It means the continuing economic growth of China is disproportionately linked to Xinjiang. Its trade routes through its eight neighbours to its wider partners will be critical to sell Chinese-made goods as well as to buy the resources needed to continue to power the country’s economy. The U.S. is the world’s leading economy and wants to keep it that way. Its doctrine of Full Spectrum Dominance asserts that it will use any means necessary to maintain the pre-eminence of U.S. capital. I think we can take this to mean that the U.S. will not hesitate to spread misinformation about China. After all, it’s not as if the U.S. does not have form for this type of behaviour. They have been doing it for years, particularly across Africa and Central America where they buy organisations to ferment internal dissent against governments deemed not to be compliant. Sprinkled with an always unhealthy dose of sinophobia the move by the U.S. to undermine the reputation of China has largely economic foundations and false allegations of mistreatment against ethnic minorities–particularly the Uighurs–are completely without foundation. On the contrary, there seems to me to be far more evidence of the Chinese at a national and regional level actively celebrating cultural diversity as well as striving to put in place the economic prosperity that looks as though it is undermining attempts by terrorist groups–likely funded by the West–to sow discontent in Xinjiang. I will talk about this and the allegations of forced labour in some detail in the second part of this three series about my visit to China. In the meantime, to anyone reading this article in disbelief and who believes that either I am lying or have been the victim of what would be a truly elaborate hoax my suggestion is: go and see for yourself. It’s a long way away but I honestly believe you will be surprised by the wonderful vibrant people and cities that will greet you. This is the first of three eyewitness articles from Morning Star international editor Roger McKenzie on his recent visit to China. AuthorRoger McKenzie This article was produced by Morning Star. Archives July 2024

0 Comments

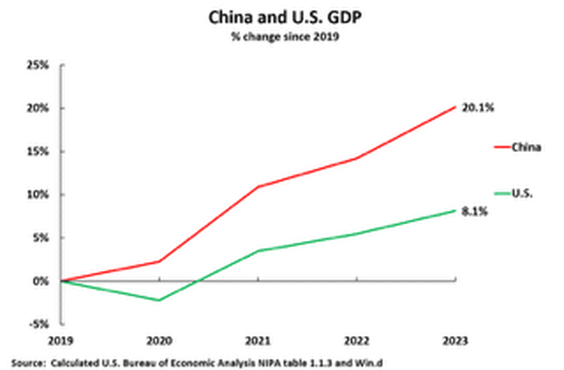

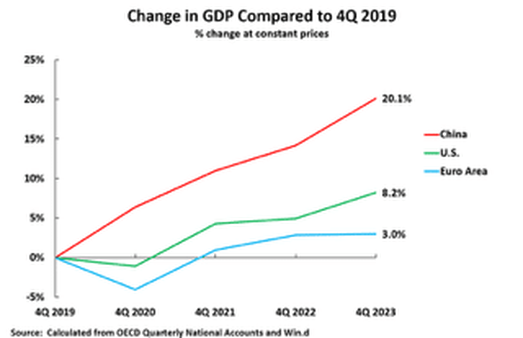

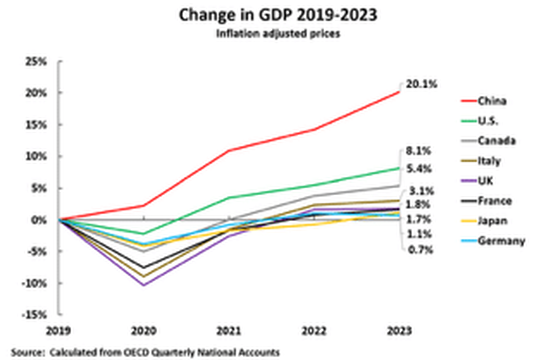

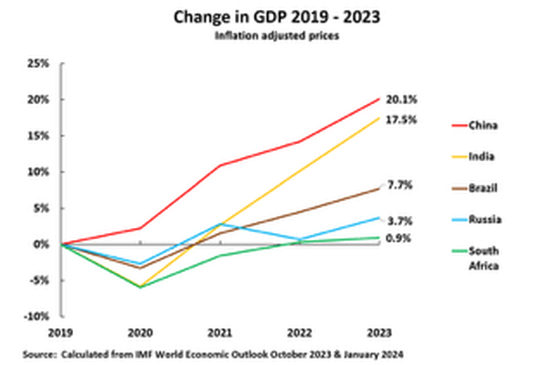

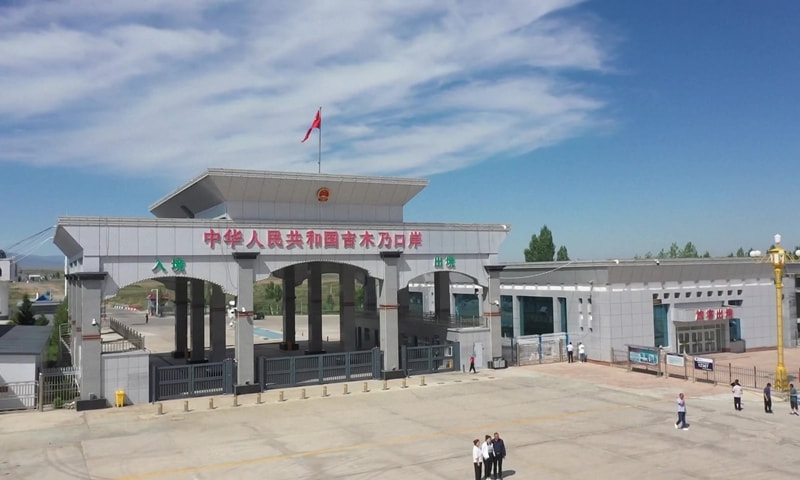

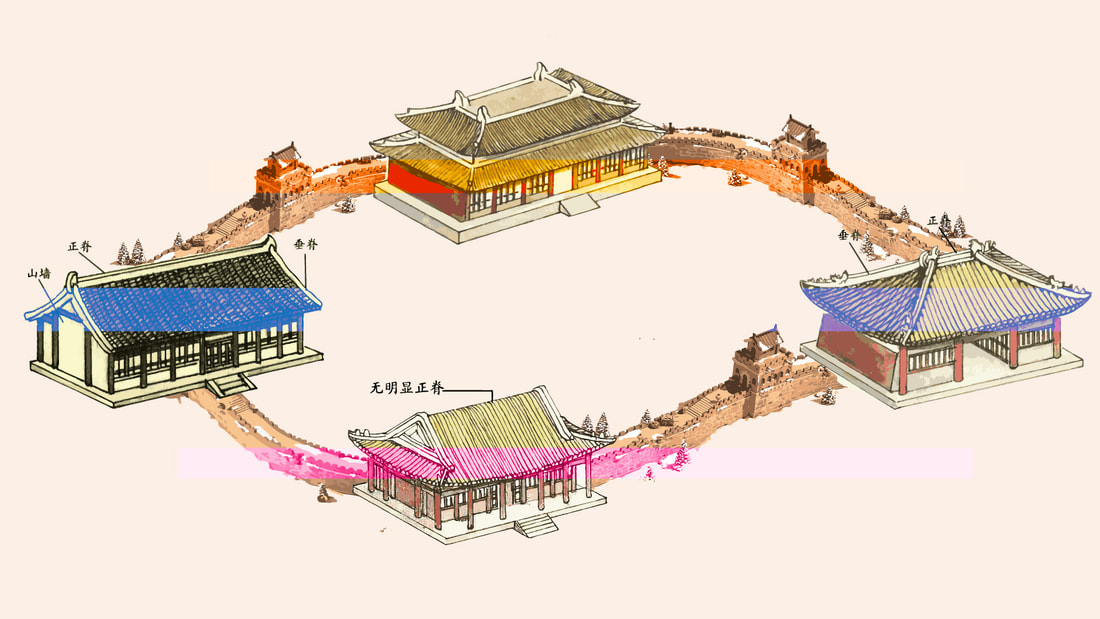

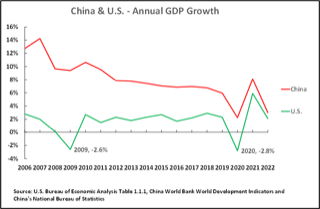

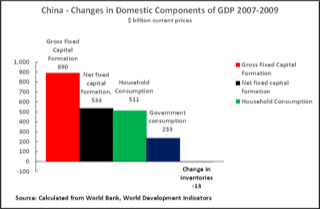

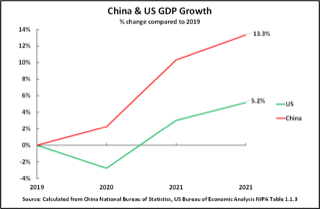

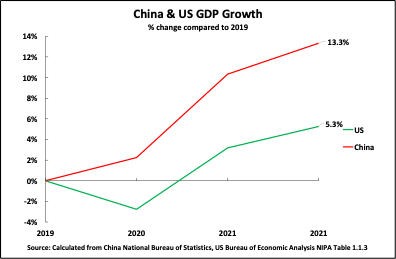

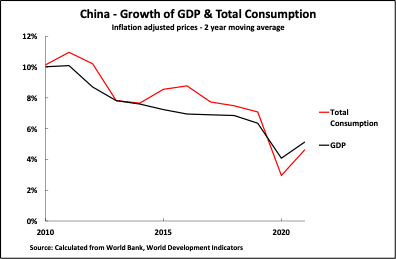

2/28/2024 China’s economy is still far out growing the U.S. – contrary to Western media “fake news. By: John RossRead NowGDP data for China, the U.S., and the other G7 countries for the year 2023 has now been published. This makes possible an accurate assessment of China’s, the U.S., and major economies performance—both in terms of China’s domestic goals and international comparisons. There are two key reasons this is important.

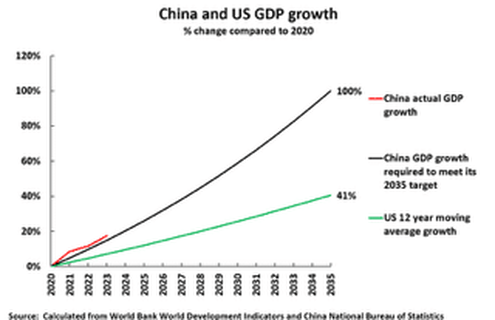

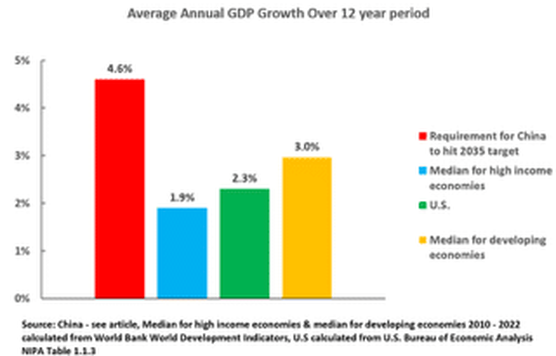

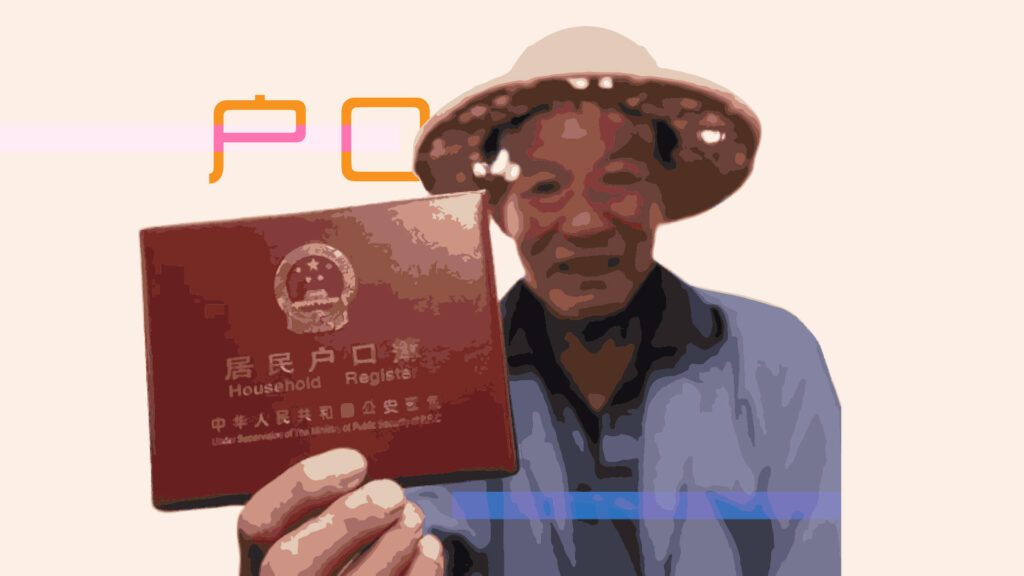

The factual situation is that China’s economy, as it heads into 2024, has far outgrown all other major comparable economies. This reality is in total contradiction to claims in the U.S. media. This in turn, therefore, demonstrates the extraordinary distortions and falsifications in the U.S. media about this situation. It confirms that, with a few honourable exceptions, Western economic journalism is primarily dominated by, in some cases quite extraordinary, “fake news” rather than any objective analysis. Both for understanding the economic situation, and the degree of distortion in the U.S. media, it is therefore necessary to establish the facts of current international developments. China’s growth targets Starting with China’s strategic domestic criteria, it has set clear goals for its economic development over the next period which will complete its transition from a “developing” to a “high-income” economy by World Bank international standards. In precise numbers, in 2020’s discussion around the 14th Five Year plan, it was concluded that for China by 2035: “It is entirely possible to double the total or per capita income”. Such a result would mean China decisively overcoming the alleged “middle income trap” and, as the 20th Party Congress stated, China reaching the level of a “medium-developed country by 2035”. In contrast, a recent series of Western reports, widely used in anti-China propaganda, claim that China’s economy will experience sharp slowdown and will fail to reach its targets. Self-evidently which of these outcomes is achieved is of fundamental importance for China’s entire national rejuvenation and construction of socialism—as Xi Jinping stated, China’s: “path takes economic development as the central task, and brings along economic, political, cultural, social, ecological and other forms of progress.” But the outcome also affects the entire global economy—for example, a recent article by the chair of Rockefeller International, published in the Financial Times, made the claim that what was occurring was China’s “economy… losing share to its peers”. The Wall Street journal asserted: “China’s economy limps into 2024” whereas in contrast the U.S. was marked by a “resilient domestic economy.” The British Daily Telegraph proclaimed China has a “stagnant economy”. The Washington Post headlined that: “Falling inflation, rising growth give U.S. the world’s best recovery” with the article claiming: “in the United States… the surprisingly strong economy is outperforming all of its major trading partners.” This is allegedly because: “Through the end of September, it was more than 7 percent larger than before the pandemic. That was more than twice Japan’s gain and far better than Germany’s anaemic 0.3 percent increase.” Numerous similar claims could be quoted from the U.S. media. U.S. use of “fake news”Reading U.S. media claims on these issues, and comparing them to the facts. it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that what is involved is deliberate “fake news” for propaganda purposes—as will be seen, the only alternative explanation is that it is disgracefully sloppy journalism that should not appear in supposedly “quality” media. For example, it is simply absurdly untrue, genuinely “fake news”, that the U.S. is “outperforming all of its major trading partners”, or that China has a “stagnant economy”. Anyone who bothers to consult the facts, an elementary requirement for a journalist, can easily find out that such claims are entirely false—as will be shown in detail below. To first give an example regarding U.S. domestic reports, before dealing with international aspects, a distortion of U.S. economic growth in 2023 was so widely reported in the U.S. media that it is again hard to avoid the conclusion that this was a deliberate misrepresentation to present an exaggerated view of U.S. economic performance. Factually, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the U.S. official statistics agency for economic growth, reported that U.S. GDP in 2023 rose by 2.5%—for comparison China’s GDP increased by 5.2%. But a series of U.S. media outlets, starting with the Wall Street Journal, instead proclaimed that the “U.S. economy grew 3.1% over the last year”. This “fake news” on U.S. growth was created by statistical “cherry picking”. In this case comparing only the last quarter of 2023 with the last quarter of 2022, which was an increase of 3.1%, but not by taking GDP growth in the year as a whole “last year”. But U.S. growth in the earlier part of 2023 was far weaker than in the 4th quarter—year on year growth in the 1st quarter was only 1.7% and in the 2nd quarter only 2.4%. Taking into account this weak growth in the first part of the year, and stronger growth in the second, U.S. growth for the year as a whole was only 2.5%—not 3.1%. As it is perfectly easy to look up the actual annual figure, which was precisely published by the U.S. statistical authorities, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this was a deliberate distortion in the U.S. media to falsely present a higher U.S. growth rate in 2023 than the reality. It may be noted that even if U.S. GDP growth had been 3.1% then China’s was much higher at 5.2%. But the real data makes it transparently clear that China’s economy grew more than twice as fast as the U.S. in 2023—showing at a glance that claims that the U.S. is “outperforming all of its major trading partners”, or that China has a “stagnant economy” were entirely “fake news”. Many more examples of U.S. media false claims could be given, but the best way to see the overall situation is to systematically present the overall facts of growth in the major economies. What China has to do to achieve its 2035 goalsTurning first to assessing China’s economic performance, compared to its own strategic goals of doubling GDP and per capita GDP between 2020 and 2035, it should be noted that in 2022 China’s population declined by 0.1% and this fall is expected to continue—the UN projects China’s population will decline by an average 0.1% a year between 2020 and 2035. Therefore, in economic growth terms, the goal of doubling GDP growth to 2035 is slightly more challenging than the per capita target and will be concentrated on here—if China’stotal GDP goal is achieved then the per capita GDP one will necessarily be exceeded. To make an international comparison of China’s growth projections compared with the U.S., the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), responsible for the official growth projections for the U.S. economy on which its government’s policies rely, estimates there will be 1.8% annual average U.S. GDP growth between 2023 and 2023—with this falling to 1.6% from 2034 onwards. This figure is slightly below the current U.S. 12-year long term annual average GDP growth of 2.3%—12 being the number of years from 2023 to 2035. To avoid any suggestion of bias against the U.S., and in favour of China, in international comparisons here the higher U.S. number of 2.3% will be used. The results of such figures are that if China hits its growth target for 2035, and the U.S. continues to grow at 2.3%, then between 2020 and 2035 China’s economy will grow by 100% and the U.S. by 41%—see Figure 1. Therefore, from 2020 to 2035, China’s economy would grow slightly more than two and a half times as fast as the U.S. The strategic consequences of China’s economic growth rate The international implications of any such growth outcomes were succinctly summarised by Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times. If China’s economy continues to grow substantially faster than Western ones, and it achieves the status of a “medium-developed country by 2035”, then, in addition to achieving high domestic living standards, China’s will become by far the world’s largest economy. As Wolf put it: “The implications can be seen in quite a simple way. According to the IMF, China’s gross domestic product per head (measured at purchasing power) was 28 per cent of U.S. levels in 2022. This is almost exactly half of Poland’s relative GDP per head… Now, suppose its [China’s] relative GDP per head doubled, to match Poland’s. Then its GDP would be more than double that of the U.S. and bigger than that of the U.S. and EU together.” By 2035 such a process would not be completed on the growth rates already given, and measuring by Wolf’s chosen measure of purchasing power parities (PPPs) China’s economy by 2035 would be 60% bigger than that of the U.S. But even that would make China by far the world’s largest economy. Wolf equally accurately notes that the only way that such an outcome would be prevented from occurring is if China’s economy slows down to the growth rate of a Western economy such as the U.S. Clearly, if China’s economic growth slows to that of a Western economy, then, naturally, China will never catch up with the West—it will necessarily simply stay the same distance behind. Therefore. as Wolf accurately puts it the outcomes are: What is the economic future of China? Will it become a high-income economy and so, inevitably, the largest in the world for an extended period, or will it be stuck in the ‘middle income’ trap, with growth comparable to that of the U.S.? The progress in achieving China’s strategic economic goalsTurning to the precise figure required to achieve China’s 2035 target, China’s goal of doubling GDP required average annual growth of at least 4.7% a year between 2020 and 2035. So far China, as Figure 1 shows, is ahead of this goal—annual average growth in 2020-2022 was 5.7%, meaning that from 2023-2035 annual average 4.6% growth is now required. China’ 5.2% GDP increase in 2023 therefore once again exceeded the required 4.6% growth rate to achieve its 2035 goal—as shown in Figure 1. From 2020 to 2023 the required total increase in China’s GDP to hit its 2035 target was 14.9%, whereas in fact its growth was 17.5%. This is in line with the 45-year record since 1978’s Reform and Opening Up, during which entire period the medium/long term targets set by China have always been exceeded. Therefore. to summarise, there is no sign whatever in 2023, or indeed in the period since 2020, that China will fail to meet its target of doubling GDP between 2020 and 2035—China is ahead of this target. Such a 4.6% growth rate would easily ensure China becomes a high-income economy by World Bank criteria well before 2035—the present criteria for this being per capita income of $13,846. It should be noted, as discussed in in detail below, that a clear international conclusion flows from this necessary 4.6% annual average growth rate for China to achieve its strategic goals. It means that China must continue to grow much faster than the Western economies throughout this period to 2035—that is in line with China’s current trend. However, if China were to slow down to the growth rate of a Western economy, then it will fail to achieve its strategic goals to 2035, may not succeed in becoming a high income economy, and will necessarily remain the same distance behind the West as now. The implications of this will be considered below. Systematic comparisons not “cherry picking”Having considered China’s performance in 2023 terms of achieving its own domestic strategic goals we will now turn to actual results and a comparison of China with other international economies. This immediately shows the factual absurdity, the pure “fake news” of claims such as that the U.S. has “the world’s best recovery“ and “the United States… is outperforming all of its major trading partners.” On the contrary China has continued to far outgrow the U.S. economy not only in 2023 but in the entire last period. China’s outperformance of the other major Western economies, the G7, is even greater that of the U.S. Entirely misleading claims regarding such international comparisons, used for propaganda as opposed to serious analysis, are sometimes made because data is taken from extremely short periods of time which are taken out of context—unrepresentative statistical “cherry picking” or, as Lenin put it, a statistical “dirty business”. Such a method is always erroneous, but it is particularly so during periods which were affected by the impact of the Covid pandemic as these caused extremely violent short-term economic fluctuations related to lock downs and similar measures. China’s assertion of superior growth is based on its overall performance, not an absurd claim that it outperforms every other economy, on every single measure, in every single period! Therefore, in making international comparisons, the most suitable period to take is that for since the beginning of the pandemic up to the latest available GDP data. As comparison of China with the U.S. is the most commonly made one, and particularly concentrated on by the U.S. media campaign, this will be considered first. China’s and the U.S.’s growth in 2023 It was already noted that in 2023 China’s GDP grew by 5.2% and the U.S. by 2.5%—China’s economy growing more than twice as fast as the U.S. But it should also be observed that 2023 was an above trend growth year for the U.S.—U.S. annual average growth over a 12-year period is only 2.3% and over a 20-year period it is only 2.1%. Therefore, although in 2023 China’s economy grew more than twice as fast as the U.S., that figure is actually somewhat flattering for the U.S. Figure 2shows that in the overall period since the beginning of the pandemic China’s economy has grown by 20.1% and the U.S. by 8.1%—that is China’s total GDP growth since the beginning of the pandemic was two and half times greater than the U.S. China’s annual average growth rate was 4.7% compared to the US’s 2.0%. Economic performance of China and the three major global economic centres Turning to wider international comparisons than the U.S. such data immediately shows the extremely negative situation in most “Global North” economies and China’s great outperformance of them. To start by analysing this in the broadest terms, Figure 3 shows the developments in the world’s three largest economic centres—China, the U.S., and the Eurozone. These three together account for 57% of world GDP at current exchange rates and 46% in purchasing power parities (PPPs). No other economic centre comes close to matching their weight in the world economy. Regarding the relative performance of these three major economic centres, at the time of writing data has not been published for the Euro Area for the whole year of 2023 —which would be the ideal comparison. However, it has been published for the the Euro area for the four quarters of 2023 individually and trends can be calculated on that basis. These show that In the four years to the 4th quarter of 2023, covering the period since the beginning of the pandemic, China’s economy has grown by 20.1%, the U.S. by 8.2%, and the Eurozone by 3.0%. China’s economy therefore grew by two and a half times as fast as the U.S. while the situation of the Eurozone could accurately be described as extremely negative with annual average GDP growth in the last four years of only 0.7%. Such data again makes it immediately obvious that claims in the Western media that China faces economic crisis, and the Western economies are doing well is entirely absurd—pure fantasy propaganda disconnected from reality. Relative performance of China and the G7 Turning to analysing individual countries, then comparing China to all G7 states, i.e. the major advanced economies, shows the situation equally clearly—see Figure 4. Data for China and all G7 economies has now been published for the whole of 2023. The huge outperformance by China of all the major advanced economies is again evident. Over the four years since the beginning of the pandemic China’s economy grew by 20.1%, the U.S. by 8.1%, Canada by 5.4%, Italy by 3.1%, the UK by 1.8%, France by 1.7%, Japan by 1.1% and Germany by 0.7%. In the same period China’s economy therefore grew two and a half times as fast as the U.S., almost four times as fast as Canada, almost seven times as fast as Italy, 11 times as fast as the UK, 12 times as fast as France, 18 times as fast as Japan and almost 29 times as fast as Germany. In terms of annual average GDP growth during this period China’s was 4.7%, the U.S. 2.0%, Canada 1.3%, Italy 0.8%, the UK 0.4%, France 0.4%, Japan 0.3% and Germany 0.2%. It may therefore be seen that China’s economy far outperformed the U.S., while the performance of all other major G7 economies may be quite reasonably described as extremely negative—all having annual average economic growth rates of around or even under 1%. Comparison of China to developing economies A comparison using the IMF’s January 2024 projections can also be made to the major developing economies—the BRICS. Figure 5 shows this, using the factual result for China and the IMF projections for the other countries. Over the period since the start of the pandemic, from 2019-2023, China’s GDP grew by 20.1%, India by 17.5%, Brazil by 7.7%, Russia by 3.7% and South Africa by 0.9%. This data confirms that the major Global South economies are growing faster than most of the major Global North economies, which is part of the rise of the Global South and draws attention to the good performance of India. But China grew more than two and half times more than all the BRICS economies except India—China’s growth was 15% greater than India’s. It should be noted that India is at a far lower stage of development than the other BRICS economies—all the others fall in the World Bank classification of upper middle-income economies whereas India falls into the lower middle income group. Comparison of China’s growth to Western economies Finally, this outperformance by China casts light on what is necessary to achieve its own 2035 strategic targets. China’s 4.6% growth rate necessary to meet these goals means that it must continue to maintain a growth rate far higher than Western economies—Figure 6 shows this in overall terms in addition to individual comparisons given to major economies above. Whereas China must achieve an annual average 4.6% growth rate the median growth rate of high income “Western” economies is only 1.9%, the U.S. is 2.3%, and the median for developing economies is 3.0%.That is, to achieve its 2035 goals China must grow twice as fast as the long term trend of the U.S., almost two and a half times as fast as the median for high income economies, and more than 50% faster than the median for developing economies. As already seen, China is more than achieving this. But such facts immediately show why it is an extremely misleading when proposals are made that China should move towards the macro-economic structure of a Western economy. If China adopts the structure of a Western economy then, of course, China will slow down to the same growth rate as Western economies—and therefore fail to achieve its 2035 economic goals. China will be precisely stuck in the negative outcome of the situation accurately diagnosed by Martin Wolf. What is the economic future of China? Will it become a high-income economy and so, inevitably, the largest in the world for an extended period, or will it be stuck in the ‘middle income’ trap, with growth comparable to that of the U.S.? Conclusion In conclusion, it addition to objectively analysing 2023’s economic results, it is also necessary in the light of this factual situation to make a remark regarding Western, in particular U.S. “journalism”. None of the data given above is secret, all is available from public readily accessible sources. In many cases it does not even require any calculations and simply published data can be used. But the U.S. media and journalists report information that is systematically misleading and in many cases simply untrue. While it lagged China in creating economic growth the U.S. was certainly the world leader in creating “fake economic news”! What was the reason, what attitude should be taken to it? First, to avoid accusations of distortion, it should be stated that there were a small handful of Western journalists who refused to go along with this type of distortion and fake news. For example Chris Giles, the Financial Times economics commentator, in December, sharply attacked “an absurd way to compare economies… among people who should know better.” Giles did not do this because of support for China but because, quite rightly, he warned that spreading false or distorted information led to serious errors by countries doing so: “Coming from the UK, which lost its top economic dog status in the late 19th century but still has some delusions of grandeur, I can understand American denialism… But ultimately, bad comparisons foster bad decisions.” But the overwhelming majority of U.S. and Western journalists continued to spread fake news. Why? First, the fact that identical distortions and false information appeared absolutely simultaneously across a very wide range of media makes it clear that undoubtedly U.S. intelligence services were involved in creating it—i.e. part of the misrepresentation and distortions were entirely deliberate and conscious, aimed at disguising the real situation. Second, another part was merely sloppy journalism—that is journalists who could not be bothered to check facts. Third, supporting both of these factors was “white Western arrogance”—an arrogant assumption, rooted in centuries of European and European descended countries dominating the world, that the West must be right. Therefore, such arrogance made it impossible to acknowledge or report the clear facts that China’s economy is far outperforming the West. But whether it was conscious distortion, sloppy journalism, or conscious or unconscious arrogance, in all these cases no respect should be given to the Western “quality” media. It is not trying to find out the truth, which is the job of journalism, it is simply spreading false propaganda. It remains a truth that if a theory and the real world don’t coincide there are only two courses that can be taken. The first, that of a sane person, is to abandon the theory. The second, that of a dangerous one, is to abandon the real world—precisely the danger that Chris Giles pointed to. What has been appearing in the Western media about international economic comparisons regarding China is precisely abandonment of the real world in favour of systematic fake news. This is a shortened version of an article that originally appeared in Chinese at Guancha.cn. About John Ross is a senior fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He was formerly director of economic policy for the mayor of London. Republished from Monthly Review Archives February 2024 10/12/2023 A decade of BRI development transforms China's Xinjiang region into a core area of the Silk Road Economic Belt By: Li Xuanmin in Urumqi and HorgosRead NowA decade of BRI development transforms the region into a core area of the Silk Road Economic Belt On Sunday morning, workers were harvesting grapes on farmland in Yining county in Kazak Autonomous Prefecture of Ili, Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The freshly-picked fruit was then uploaded onto a truck, headed to Kazakhstan via highway, and within six hours, it would be delivered to the Kazakhstani market and sold to the local consumers. "It used to take two to three days to ship goods from Xinjiang to Kazakhstan, but the time has been reduced to only half a day since the development of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), under which connectivity has been facilitated and the efficiency of customs clearance has been largely improved," Yu Chengzhong, chairman of Horgos Jinyi International Trade Co, told the Global Times. Yu's company is growing quickly thanks to fruit exports from Xinjiang, including apples, nectarines, grapes, peppers, tomatoes, prunes and cucumbers to markets in Central Asia, Russia, and Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand and Vietnam. It is expected that the company's export value to Central Asia could climb up to $1.2 billion this year, almost doubling from $683 million recorded last year. As business expands, the company is now constructing a 500,000-square-meter overseas warehouse in Alma-Ata in southern Kazakhstan, and it is scheduled to be put into use in October 2024. "It will be built into a distribution center covering other Central Asian countries and Russia. We will also set up an exhibition area for China-produced vehicles, as those autos have been gaining popularity in those markets," Yu added Yu's company is one among the thousands of firms in Xinjiang whose businesses have been taking off under the BRI. As the China-proposed BRI being materialized over the past decade, Xinjiang - which sits at China's westernmost frontier bordering eight countries including Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India - has been transformed from a relatively closed inland region to a frontier of opening-up. A view of China- Kazakhstan International Cooperation Center in Horgos, Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region on September 16. Photo: Li Xuanmin/GT As an important node along the BRI, the region, leveraging its strategic location, has built up an overarching rail, road and flight transportation network that not only fosters closer trade and economic ties with Central Asia and Europe, but also shapes itself into a bridgehead for westward opening-up, company representatives and local officials noted. "What we felt most during the past 10 years is that Xinjiang is no longer a remote region, but it is now becoming a core area of the Silk Road Economic Belt. We're a pivotal international logistic hub placed at the Asia-Europe 'golden passage.' And the region is set to be designated with more important missions in the country's further opening-up," Zhao Yi, general manager assistant at International Land Port in Urumqi, told the Global Times. Flourishing foreign trade In the first eight months of 2023, Xinjiang's foreign trade surged by 51.2 percent year on year, reaching 219.19 billion yuan (around $30 billion). Xinjiang has engaged in foreign trade with 170 countries and regions this year. Its foreign trade with five Central Asian countries grew by 59.1 percent year-on-year to 176.64 billion yuan, accounting for 80.6 percent of the regional total, customs data showed. "The main cargo shipped from Xinjiang to the international market are typically ketchup, agricultural products, textiles, PVC, chemical raw materials, equipment and machineries," Zhao explained, as he guided the loading of containers into a China-Europe freight train set to depart for Kazakhstan on Sunday afternoon. As of early September, the inbound and outbound China-Europe freight trains passing through Xinjiang have totaled 10,017 this year, up 10.1 percent year-on-year, according to China Railway Urumqi Group Co Ltd. In the first seven months of 2023, the International Land Port in Urumqi opened 772 China-Europe freight trains, up 9.35 percent year-on-year. The rail routes connect with 26 cities in 19 countries. The port also serves as an important transit point for goods across China and from Southeast Asia to be transported to Europe. Ding Zhijun, an official from the Urumqi Economic and Technological Development Zone, told the Global Times that since the beginning of this year, goods from Laos, such as sugar and rubber, have been transferred at the port via China-Laos Railway and other inland railway routes, and then are assembled and delivered to European markets. "The BRI has driven up Xinjiang's foreign trade, which is a boon for local industries. It is also conducive to Xinjiang's economic development and boosting employment opportunities," Ding said. He added that looking to the future, the port authorities plan to set up a textile trading center within the port, to facilitate the exports and trade of clothes and other textile products. Opening to the West The hustle and bustle of international cooperation in Xinjiang is also seen throughout the China-Kazakhstan International Cooperation Center in Horgos, which is home to China's first cross-border free trade zone. When Global Times reporters visited the center at a weekend in mid-September, streams of tourists were standing at the border gate and taking photos, and stores were crowded with merchants and buyers. "In the initial stage when we set up the shopping mall in 2015, most merchants were from Kazakhstan and China. But now, with the steady progress of BRI, the center has become a hot destination for foreign investment, and there are more vendors from other Central Asia countries as well as Russia and South Korea," Ji Gang, general manager of Jindiao Central Square, a shopping mall at the cooperation center, told the Global Times. According to Ji, the center has just held a commercial fair for Central Asian business leaders in August, during which a number of deals were signed, including equipment purchase agreements. Some Chinese and Kazakhstani companies also reached initial agreement to open factories in Kazakhstan. "With unique geographic advantage, Xinjiang has become an important gateway for China to open up to the West. It is worth noting that the radiation effect of the region is not confined to China, but also to Central Asia and Europe, which would in turn provide Xinjiang with more development opportunities," Ji added. Zhao also said that the International Land Port is planning to open more China-Europe freight train routes that directly connect the region to Europe. "In particular, we aim to set up some premium routes to transport electronic components and local specialty goods via the China-Europe railway express. This year, we are also actively engaging with Kazakhstan to establish business partnerships and enhance customs clearance efficiency," Zhao noted. AuthorLi Xuanmin in Urumqi and Horgos This article was produced by Global Times. Archives October 2023 With over 20 million inhabitants each, Shanghai and Beijing are among the “hypercities” of the Global South, including Delhi, São Paulo, Dhaka, Cairo, and Mexico City, far surpassing the “megacities” of the Global North like London, Paris, or New York1. Walking the streets in China’s cities, you will however, quickly notice one marked difference – the absence of large slums or pervasive homelessness that is so common to most of the rest of the world. Why did mass urbanization not create large slums in China?When reform and opening up began in the late 1970s, 83 percent of China’s population lived in the countryside. By 2021, the proportion of the rural population had fallen to 36 percent. During this period of mass urbanization, over 600 million people migrated from rural areas to cities. Today, there are 296 million internal “migrant workers” (农民工, nóngmín gōng), comprising over 70 percent of the country’s total workforce2. Migrant workers became the economic engine of China’s rapid growth, which created the world’s largest middle class of 400 million people. This historic migration came with many challenges, including the emergence of “urban villages” that had poor living conditions and inadequate infrastructure. Although basic amenities – such as running water, electricity, gas, and communications – were provided, sanitation, public services, fire safety, and other such amenities resembled that of rural villages. Due to lower rents and the lack of other affordable housing, urban villages are largely inhabited by migrant workers. With the acceleration of urbanization in the 2000s, the Chinese government began to promote large-scale transformation of the old areas of the cities, focusing on renovation of historically deteriorated neighborhoods and the removal of dangerous housing. Between 2008 and 2012, 12.6 million households in urban villages were rebuilt nationwide3. At the same time, efforts were made to construct public rental or low-rent housing. For instance, in Shanghai today, families of three or more people with a monthly income of less than 4,200 yuan per person can apply for low-rent housing, with the monthly rent being just a few hundred yuan (or five percent of monthly household income). In 2022, the central government announced the construction of 6.5 million units of low-cost rental housing in 40 cities, representing 26 percent of the total new housing supply in the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025)4. Indeed the explosion of rural-to-urban migration in recent decades is not a phenomenon unique to China. While understanding that there are different definitions of “slums” used by countries and international organizations, they all point to the same tendency: since the 1970s, slum growth outpaced urbanization rates across the Global South. China’s efforts to upgrade existing precarious housing or build new affordable housing does not, however, explain why China did not develop slums like in so many other countries. Urbanization in China, therefore, must be understood within the context of socialist construction. What is the “hukou” system and what does it have to do with socialism? One unique characteristic of China’s urbanization process is that, although policies encouraged migration to cities for industrial and service jobs, rural residents never lost their access to land in the countryside. In the 1950s, the Communist Party of China (CPC) led a nationwide land reform process, abolishing private land ownership and transforming it into collective ownership. During the economic reform period, beginning in 1978, a “Household Responsibility System” (家庭联产承包责任制 jiātíng lián chǎn chéngbāo zérèn zhì) was created, which reallocated rural agricultural land into the hands of individual households. Though agricultural production was deeply impacted, collective land ownership remained and land was never privatized. Today, China has one of the highest homeownership rates in the world, surpassing 90 percent, and this includes the millions of migrant workers who rent homes in other cities. This means that when encountering economic troubles, such as unemployment, urban migrant workers can return to their hometowns, where they own a home, can engage in agricultural production, and search for work locally. This structural buffer plays a critical role in absorbing the impacts of major economic and social crises. For example, during the 2008 global financial crisis, China’s export-oriented economy, especially of manufactured goods, was severely hit, causing about 30 million migrant workers to lose their jobs. Similarly, during the Covid-19 pandemic, when service and manufacturing jobs were seriously impacted, many migrant workers returned to their homes and land in the countryside. Beyond land reform, a system was created to manage the mass migration of people from the countryside to the cities, to ensure that the movement of people aligned with the national planning needs of such a populous country. Though China has had some form of migration restriction for over 2,000 years, in the late 1950s, the country established a new “household registration system” (户口 or hùkǒu) to regulate rural-to-urban migration. Every Chinese person has an assigned urban or rural hukou status that grants them access to social welfare benefits (subsidized public housing, education, health care, pension, and unemployment insurance, etc.) in their hometown, but which are restricted in the cities they move to for work. While reformation of the hukou system is ongoing, the lack of urban hukou status forces many migrant parents to spend long periods away from their families and they must leave their children in their grandparents’ care in their hometowns, referred to as “left-behind children” (留守儿童 liúshǒu értóng). Though the number has been decreasing over the years, there are still an estimated seven million children in this situation. Today, 65.22 percent of China’s population lives in cities, but only 45.4 percent have urban hukou. Although this system deterred the creation of large urban slums, it also reinforced serious inequities of social welfare between urban and rural areas, and between residents within a city based on their hukou status. How does the Chinese government deal with homelessness? In the early 2000s, the issues of residential status, rights of migrant workers, and treatment of urban homeless people became a national matter. In 2003, the State Council – the highest executive organ of state power – issued the “Measures for the Rescue and Management of Itinerant and Homeless in Urban Areas”5. The new regulation created urban relief stations providing food rations and temporary shelters, abolished the mandatory detention system of people without hukou status or housing, and placed the responsibility on the local authorities for finding housing for homeless people in their hometowns. Under these measures, cities like Shanghai have set up relief stations for homeless people. When public security – the local police – and urban management officials encounter homeless people, they must assist them in accessing nearby relief stations. All costs are covered by the city’s fiscal budget. For example, the relief management station in Putuo District (with the fourth lowest per capita GDP of Shanghai’s 16 districts and a resident population of 1.24 million), provided shelter and relief to an average of 24.3 homeless people a month from June 2022 to April 2023, which could include repeated cases6. Relief stations provide homeless people with food and basic accommodations, help those who are seriously ill access healthcare, assist them to return to the locations of their household registration by contacting their relatives or the local government, and arrange free transportation home when needed. Upon returning home, the local county-level government is responsible to help the homeless people, including contacting relatives for care and finding local employment. For a very small number of people who are elderly, have disabilities, or do not have relatives nor the ability to work, the local township people’s government, or the Party-run street office, will provide national support for them in accordance with the “method of providing for extremely impoverished persons”, which is stipulated in the 2014 “Interim Measures for Social Assistance”. The content of the support includes providing basic living conditions, giving care to impoverished individuals who cannot take care of themselves, providing treatment for diseases, and handling funeral affairs, etc. This series of relief management measures ensure that administrative law enforcement personnel in the city do not simply expel homeless people from the city, but must guarantee that they receive proper assistance, in terms of housing, work, and support systems. What are the current challenges of urbanization, migration, and inequality? While creating relief centers is an important advancement, it is clear that shelters are not a structural solution and they alone cannot meet the needs of a metropolis like Shanghai of 25 million people, let alone the country’s 921 million urban residents. The government has been implementing many structural reforms to address inequality, and to make the cities and the countryside more liveable. In his report to the 20th National Congress of the CPC, President Xi Jinping said: “We have identified the principal contradiction facing Chinese society as that between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life, and we have made it clear that closing this gap should be the focus of all our initiatives.”7 The unbalanced and inadequate development points to the gap between the countryside and cities, between underdeveloped and industrialized regions, and between the rich and poor. On a broader scale, the anti-poverty campaigns – highlighted by the eradication of extreme poverty in 2020 – and the rural revitalization strategy have helped alleviate the pressure of migrant workers moving to the cities. The government has invested substantial funds and resources, using diversified ways to alleviate poverty beyond income-transfer schemes, including developing rural industry, education, health care, and infrastructure8. These measures fundamentally improved the living and employment environment in rural areas and created more opportunities so that people have the option to stay and work in the countryside. For example, every year, more migrants are returning from cities back to their hometowns, which increased from 2.4 million (2015) to 8.5 million people (2019). Over the last decade, China has implemented reforms to balance the easing of hukou residency requirements and to improve the social welfare of migrant workers, while ensuring that urbanization and population distribution responds to the country’s needs. Since 2010, major cities have gradually relaxed the household registration restrictions for school admission, allowing children of migrant workers to attend public schools like children with local hukou. Furthermore, according to the 2019 Urbanization Plan, cities with populations below three million people are required to remove all hukou restrictions, while bigger cities (under five million) can begin to relax restrictions. The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) and the country’s economic strategy until 2035 focus on redistributing income through tax reform, reducing the gap between the rich and poor, and removing the barriers that prevent millions of migrant workers from enjoying the full benefits of urban life. In 2021, the government invested US$5.3 billion to relax the hukou residency rules, and to also boost urban migrants’ spending power as part of the country’s “dual circulation” policy9. These efforts to tackle the “three mountains” of the high cost of housing, education, and health care faced by all Chinese people, including migrants, is at the center of the government’s vision and policy reforms towards “common prosperity” for all its citizens and the building of a modern socialist society.

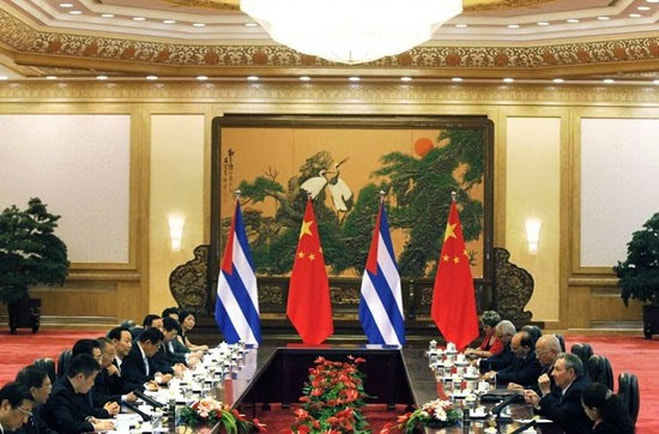

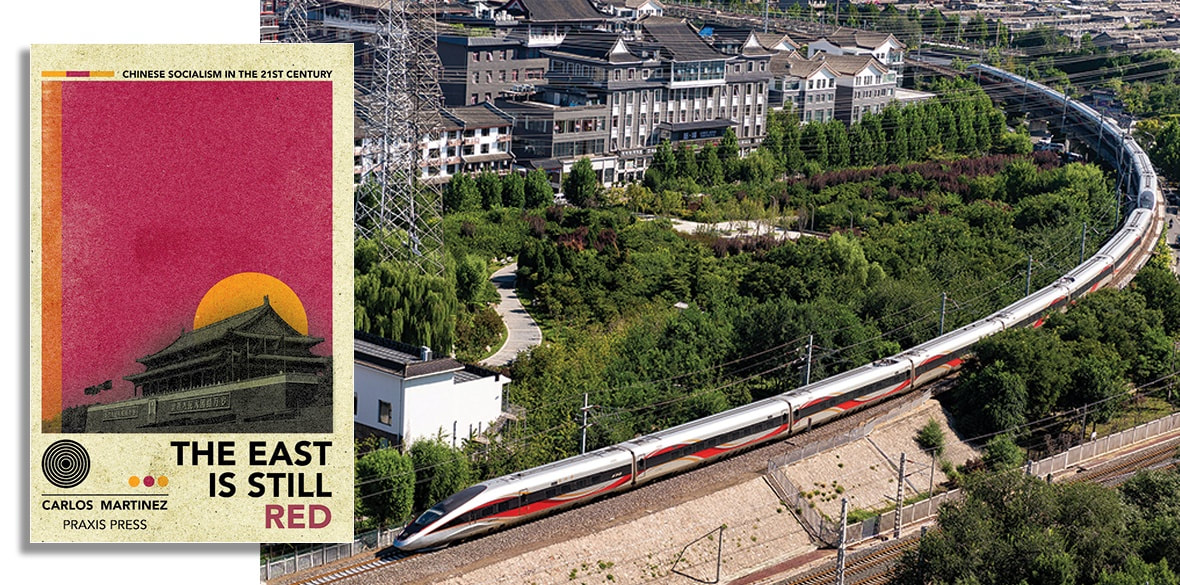

AuthorDongsheng This article was produced by DongSheng. Archives July 2023 7/12/2023 Can China and the United States Establish Mutual Respect to Lessen Tensions? By: Vijay PrashadRead NowOn June 3, 2023, naval vessels from the United States and Canada conducted a joint military exercise in the South China Sea. A Chinese warship (LY 132) overtook the U.S. guided-missile destroyer (USS Chung-Hoon) and speeded across its path. The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command released a statement saying that the Chinese ship “executed maneuvers in an unsafe manner.” The spokesperson from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wang Wenbin, responded that the United States “made provocations first and China responded,” and that the “actions taken by the Chinese military are completely justified, lawful, safe, and professional.” This incident is one of many in these waters, where the United States conducts what it calls Freedom of Navigation (FON) exercises. These FON actions are given legitimacy by Article 87(1)(a) of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea. China is a signatory to the Convention, but the United States has refused to ratify it. U.S. warships use the FON argument without legal rights or any United Nations Security Council authorization. The U.S. Freedom of Navigation Program was set up in 1979, before the Convention and separate from it. Hours after this encounter in the South China Sea, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin spoke at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. The Shangri-La Dialogue, which has taken place annually at the Shangri-La Hotel since 2002, brings together military chiefs from around Asia with guests from countries such as the United States. At a press gaggle, Austin was asked about the recent incident. He called upon the Chinese government “to reign in that kind of conduct because I think accidents can happen that could cause things to spiral out of control.” That the incident took place because a U.S. and Canadian military exercise took place adjacent to Chinese territorial waters did not evoke any comment from Austin. He emphasized the role of the United States to ensure that any country can “sail the seas and fly the skies in international space.” Austin’s pretense of innocence was challenged by his Chinese counterpart, Defense Minister Li Shangfu. “Why did all these incidents happen in areas near China,” Li asked, “not in areas near other countries?” “The best way to prevent this from happening is that military vessels and aircraft not come close to our waters and airspace… Watch out for your own territorial waters and airspace, then there will not be any problems.” Li contested the idea that the U.S. navy and air force are merely conducting FON exercises. “They are not here for innocent passage,” he said. “They are here for provocation.” Tighten the NetWhen Austin was not talking to the press, he was busy in Singapore strengthening U.S. military alliances whose purpose is to tighten the net around China. He held two important meetings, the first a U.S.-Japan-Australia trilateral meeting and the second a meeting that included their counterpart from the Philippines. After the trilateral meeting, the ministers released a sharp statement that used words (“destabilizing” and “coercive”) that raised the temperature against China. Bringing in the Philippines to this dialogue, the U.S. egged on new military cooperation among Canberra, Manila, and Tokyo. This builds on the Japan- Philippines military agreement signed in Tokyo in February 2023, which has Japan pledging funds to the Philippines and the latter allowing the Japanese military to conduct drills in its islands and waters. It also draws on the Australia-Japan military alliance signed in October 2022, which—while it does not mention China—is focused on the “free and open Indo-Pacific,” a U.S. military phrase that is often used in the context of the FON exercises in and near Chinese waters. Over the course of the past two decades, the United States has built a series of military alliances against China. The earliest of these alliances is the Quad, set up in 2008 and then revived after a renewed interest from India, in November 2017. The four powers in the Quad are Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. In 2018, the United States military renamed its Pacific Command (set up in 1947) to Indo-Pacific Command and developed an Indo-Pacific Strategy, whose main focus was on China. One of the reasons to rename the process was to draw India into the structure being built by the United States, emphasizing the India-China tensions around the Line of Actual Control. The document shows how the U.S. has attempted to inflame all conflicts in the region—some small, others large—and put itself forward as the defender of all Asian powers against the “bullying of neighbors.” Finding solutions to these disagreements is not on the agenda. The emphasis of the Indo-Pacific Strategy is for the U.S. to force China to subordinate itself to a new global alliance against it. Mutual RespectDuring the press gaggle in Singapore, Austin suggested that the Chinese government “should be interested in freedom of navigation as well because without that, I mean, it would affect them.” China is a major commercial power, he said, and “if there are no laws, if there are no rules, things will break down for them very quickly as well.” China’s Defense Minister Li was very clear that his government was open to a dialogue with the United States, and he worried as well about the “breakdown” of communications between the major powers. However, Li put forward an important precondition for the dialogue. “Mutual respect,” he said, “should be the foundation of our communications.” Up to now, there is little evidence—even less in Singapore despite Austin’s jovial attitude—of respect from the United States for the sovereignty of China. The language from Washington gets more and more acrid, even when it pretends to be sweet. AuthorVijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives July 2023 7/9/2023 Addressing allegations of “Chinese spy base” in Cuba.By: Manolo De Los Santos & Kate GonzalesRead NowOn June 8, the U.S. media added to its long storybook of tales to scare people away from normal relations with Cuba. The Wall Street Journal published an article on that day claiming that China has plans to set up a “spy base” in Cuba, to “eavesdrop” on the United States and “identify potential strike targets.” WSJ has already published two more pieces since rapidly ramping up its narrative against the Cuban state and fermenting more paranoia as the news spreads across mainstream news outlets in the United States. Meanwhile, Cuban officials held a press conference on June 8 to completely deny the allegations. Cuba’s Vice Foreign Minister Carlos de Cossío stated that “All these are fallacies promoted with the deceitful intention of justifying the unprecedented tightening of the blockade, destabilization, and aggression against Cuba and of deceiving public opinion in the United States and the world.” Even John Kirby, National Security Council spokesman who was the former press secretary for the Pentagon, has denied the WSJ report, calling it “inaccurate.” This is just one new addition to the long legacy of lies that the United States has been spinning in an attempt to further alienate the Cuban people. One just has to remember the “Havana syndrome” that mysteriously affected diplomats in Cuba; it was first blamed on foreign powers as an attack but was later revealed to have no basis. Or maybe the claims about 20,000 Cuban soldiers supposedly based in Venezuela to maintain the government there, when in reality, the vast majority of Cubans present in Venezuela were medical workers. Or perhaps the idea that Cuban doctors sent across the world are enslaved, when it is simply their understanding that their duty to humanity is to provide health care to those who need it. All of these lies have been told just in the past few years alone. These falsified stories all swirl into fomenting the atmosphere of paranoia and suspicion that prevents normal U.S.-Cuba relations. In the wake of the Havana syndrome myth, Trump was able to interrupt the path Obama set toward normalization, setting 243 additional and comprehensive sanctions, and further preventing the island from meeting its basic needs. The United States continues to live out its Cold War fantasies through these lies, at the cost of the Cuban people’s lives and well-being. And yet, it maintains its hypocrisy. Cossío was careful to point out that Cuba would never allow a foreign military base on their island, as it is a signatory of the Declaration of Latin America and the Caribbean as a Zone of Peace. Cuba is also currently sponsoring and hosting peace talks between Colombia and the National Liberation Army (ELN). As of today, they have agreed to a cease-fire, ending decades of violence in the country. Cuba already suffers from the illegal U.S. occupation of Guantanamo, to further rub salt in the wound. The United States has its infamous military base there, which is known for the inhumane treatment and torture it deals out to its prisoners. While it accuses China of military expansion, the United States has hundreds of military bases all over the globe. Cuba has demonstrated that it desires nothing but peace in the region, and normal relations with its neighbor, the United States. But the United States refuses to accept this proposal. Instead, it maintains the most comprehensive sanctions in history against the small island. Instead, it falsely places Cuba on the state sponsors of terrorism list, even though it is in fact a sponsor of peace. Instead, the U.S. government and its media apparatuses choose to fabricate myths and legends, painting Cuba as the evil monster under the bed. It chooses to scare the U.S. people away from the possibility that normal relations and ending the blockade against Cuba could be good for people from both countries. AuthorManolo De Los Santos is the co-executive director of the People’s Forum and is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He co-edited, most recently, Viviremos: Venezuela vs. Hybrid War (LeftWord Books/1804 Books, 2020) and Comrade of the Revolution: Selected Speeches of Fidel Castro (LeftWord Books/1804 Books, 2021). He is a co-coordinator of the People’s Summit for Democracy. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives July 2023 Recognising how important it is for Today’s Left to understand China, BEN CHACKO recommends a highly readable and well-researched book of essays CHINA looms large in today’s world. Its economy is predicted to exceed the US’s in size within the decade; by purchasing power parity, it is already larger. It is racing ahead too in diplomacy and trade: it has now replaced the US as the country with the most diplomatic missions overseas, and is the biggest trading partner of a majority of countries globally. This very success — China’s status as the United States’ only acknowledged “peer competitor”— could be the reason China is now routinely depicted as a menace. Britain’s BBC dutifully takes up scares over weather balloons and breathless reports on Chinese aircraft or ships’ “aggressive” conduct in encounters with US counterparts — which for some reason always take place just off the Chinese, not the American coast. Projects like the Belt & Road Initiative, which overtook the World Bank as the biggest development finance lender in 2019, are seen as evidence of a sinister new imperialism. Understanding China could hardly be more important for today’s left. The “China threat” is a key justification for a major plank of British state policy: huge increases in arms spending and the first “east of Suez” military deployments in many decades. This could mean World War III: a serving US general predicts that happening the year after next. Armageddon could result from current China policy in other ways: sanctions and economic “decoupling” are cutting us off from the world leader in renewable technology and undermining scientific co-operation on global warming or pandemics. Socialists need to know how we respond to these challenges. Carlos Martinez’s new book The East is Still Red is an excellent guide. Whether China is socialist, as its ruling Communist Party argues, is a divisive topic but with an eye on history Martinez draws out the consistencies in the country’s course since 1949. Chapter 1, No Great Wall, looks at how the “reform and opening up” period begun by Deng Xiaoping from 1978 built on achievements of the Mao years, without underrating the huge policy differences that did occur, or whitewashing either era. Later, in Will China Suffer the Same Fate as the Soviet Union, Martinez contrasts the two and points both to underlying strengths in China’s model and the lessons its party leadership has learned from the Soviet collapse. Many are familiar with impressive headline figures such as China lifting 800 million people out of poverty — but Western accounts tend to imply this is the undirected result of introducing “the market,” though capitalist market economies such as India or Brazil cannot point to similar achievements. Martinez delves into the details and looks at the targets, the plans, the actual measures taken to deliver the greatest improvement in human welfare in recorded history. For a Western left audience, key chapters are those on how China is making progress towards “ecological civilisation” — and why a “plague on both your houses” position dubbed Neither Washington Nor Beijing is untenable in a context where the US is unambiguously the aggressor in the new cold war while China’s rise is widely welcomed in the global South. Later, he adopts Noam Chomsky’s famous phrase “manufacturing consent” while looking at the media’s coverage of China and how issues are distorted to build support for our own ruling class’s hostility to it: essential reading here is a demolition of the wild claims made about alleged abuses in Xinjiang and their less than objective origins. Developed from articles written on different aspects of China and its revolution — many originally published in the Morning Star — this is a highly readable narrative that doesn’t presuppose detailed knowledge of Chinese history or politics. The thematic character means many chapters work well on their own, and will make it a handy reference point for anyone wanting to brush up on specifics like the anti-poverty campaigns or China and climate change. It’s extensively referenced, and welcome in quoting more Chinese than foreign sources on the country. Highly recommended. AuthorMorning Star This article was produced by Morning Star. Archives July 2023 The difficulty the U.S. faces in its current attempts to damage China’s economy was analysed in detail in the article “The U.S. is trying to persuade China to commit suicide”. Reduced to essentials, the U.S. problem is that it possesses no external economic levers powerful enough to derail China’s economy. The U.S. has attempted tariffs, technology sanctions, political provocations over Taiwan, the actual or threatened banning of companies such as Huawei and Tik Tok etc. But, as always, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” Taking the latest period, during the three years following the beginning of the Covid pandemic, China’s economy has grown two and a half times as fast as the U.S. and six times as fast as the E.U.. Therefore, as the previous article put it, in the economy the U.S. cannot “murder” China—even although it can create short term problems. Furthermore, unlike with Gorbachev, whose illusions in the U.S. led to a centralised political collapse of the CPSU, the disintegration of the USSR, and an historical national catastrophe for Russia, the policies of Xi Jinping and the CPC are centrally protecting China and socialism. As the U.S. cannot pursue a course of “murder”, therefore it is forced to attempt an indirect route to get China to commit “suicide”—that is, to try to persuade China to adopt policies which will damage it. Given that economic development underlies China’s success, one of the most central of all U.S. goals is to attempt to persuade China to adopt self-damaging economic policies. Enormous resources are therefore poured into spreading factually false propaganda regarding China’s economy. This also has the secondary goal of internationally attempting to persuade others not to learn from China’s economic success—because an understanding of the reality that China’s socialist economy is more efficient and successful than capitalism would be a devastating ideological blow to the U.S.. A crucial part of this false propaganda is to try to get accepted as “truth” claims about China’s economy which are entirely false—as basing policies on “facts” which are untrue would naturally lead to wrong policies. One of the most important of these false claims is that China’s socialist economy is “inefficient” compared to capitalism—or, more specifically, that investment in socialist China is inefficient in creating economic growth compared to capitalist America or in general compared to capitalist countries. Naturally, socialism’s goal is not abstract economic efficiency, it is people’s well-being. But an inefficient economy, in the long term, would be incapable of maintaining the maximum well-being of the people. Therefore, how efficient an economy is constitutes an important issue in economic development. Claims that capitalism is more economically efficient than capitalism, usually put in the form of U.S. claims of the “inefficiency of socialism”, consequently has at least two purposes. First, most immediately, to attempt to persuade China that as its investment is allegedly “inefficient” it should be reduced. As discussed in the earlier article, “The U.S. is trying to persuade China to commit suicide”, a key U.S. goal to get China to reduce its level of investment in GDP. This is because that same policy was successfully used earlier by the U.S. to derail its competitor economies of Germany, Japan and the Asian Tigers. Second, more generally and ideologically, this claim that China’s investment is inefficient, and capitalism’s is efficient, is an attempt to undermine and discredit socialism and promote capitalism. In summary, such propaganda is an attempt to spread two interrelated falsifications.

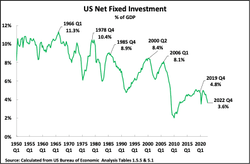

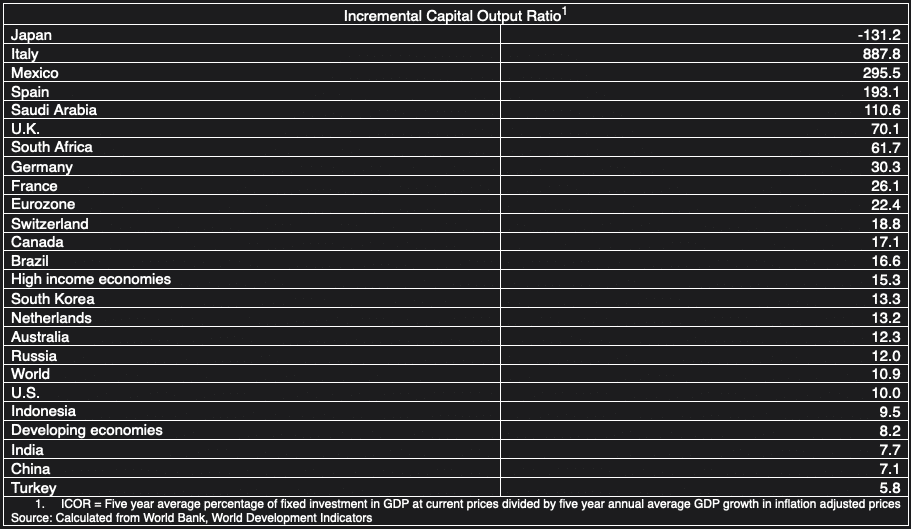

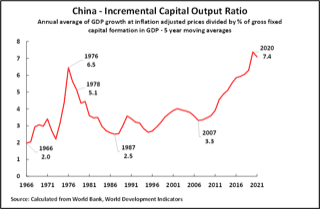

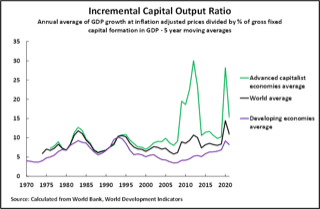

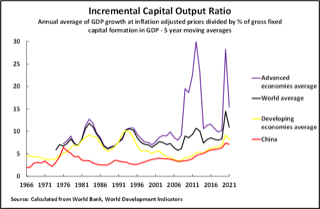

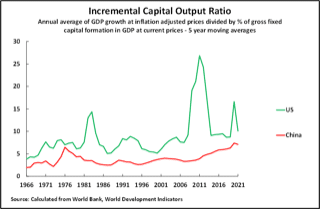

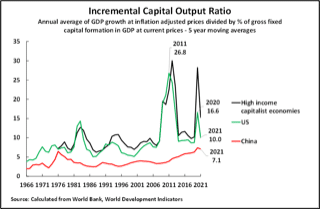

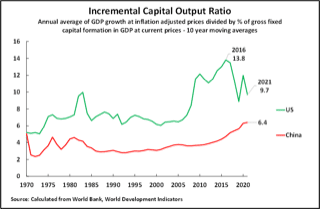

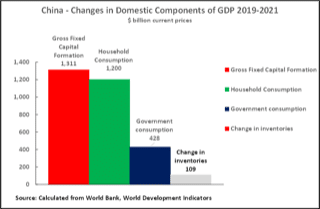

As will be systematically factually shown below, the exact reverse of these claims are true. Socialist China’s investment is much more efficient in creating growth than in capitalist countries such as the U.S.. As will be shown, this efficiency of China is integrally linked to the socialist character of its economy. As usual the method will be used to use the wise Chinese dictum to “seek truth from facts”. The first section of the article will establish the facts showing the greater efficiency of China’s investment. The second section will demonstrate that the reasons for this lie in the socialist character of China’s economy. Section 1—the high international efficiency of China’s capital investment |

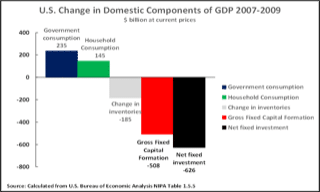

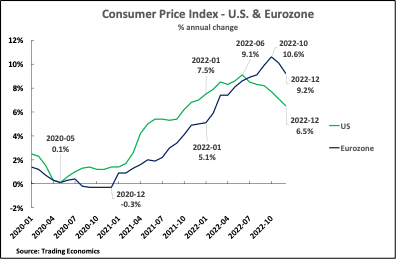

Slowdown in U.S. growth But if U.S. inflation soared during the period of its pandemic era stimulus packages U.S. economic growth was very slow. Recent publication of U.S. economic data for the whole of 2022, which means that three years of pandemic, 2020-2022, are covered shows that U.S. GDP grew by a total of only 5.3 percent during this period—an annual average 1.7 percent. |

U.S. short-term contractionary policies As is well known, to attempt to combat the inflationary wave, the U.S. Federal Reserve, and other Western central banks, have had to, and will continue for some time, to increase interest rates and tighten monetary policies with inevitable contractionary economic effects. |

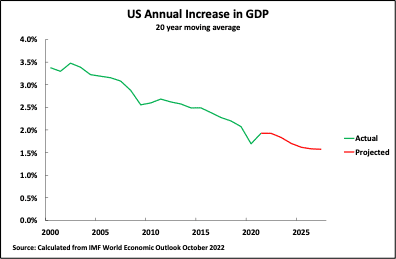

For this reason, not only will the U.S./EU’s 2023 growth decelerate, but Western economies medium/ long-term growth—in particular, that of the U.S. —will slow, as even the IMF, whose predictions are normally somewhat biased in favor of the U.S., admits. Figure 4 shows that the IMF projects that annual average U.S. GDP growth, taking a long-term average to remove the effect of business cycle fluctuations, will fall from an already low 1.9 percent in 2021 to 1.6 percent in 2027. Over the same period the IMF projects EU annual growth will fall from 1.4 percent to 1.2 percent.

This complete strategic failure of the U.S./E.U. stimulus packages launched against the COVID economic downturn makes clear why it is important that China studies and draws the lessons from this extremely negative experience—as these lessons are linked to fundamental issues of economic policy and therefore also affect China.

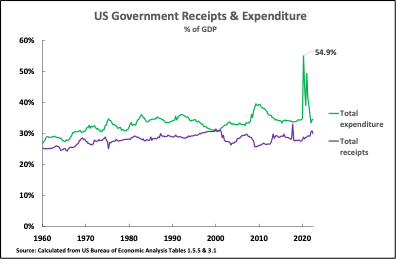

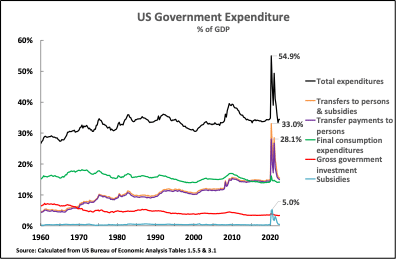

What happened during the U.S. stimulus packages? Turning from the results of the U.S. stimulus packages to the processes which occurred during them, and produced these negative results, by far the largest change was in U.S. government behavior. Figure 5 shows U.S. government receipts and expenditure. |

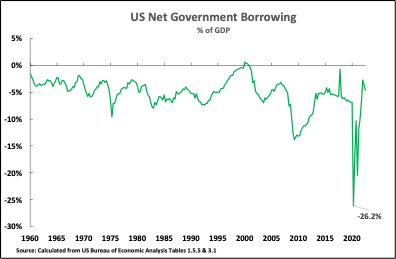

| The vast surge in U.S. government expenditure, with merely a moderate rise in receipts, of course produced a huge excess of expenditure over income and consequently a vast increase in the budget deficit and state borrowing. As Figure 6 shows U.S. government quarterly borrowing soared to an unprecedented peacetime level of 26.2 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2020. |

A huge increase in U.S. transfer payments and subsidies

- There was no increase in government investment—it was 3.5 percent of GDP at the beginning of the period and 3.5 percent at the end.

- Government final consumption rose only modestly from 14.1 percent to 16.1 percent of GDP—an increase of 2.0 percent of GDP.

- Government subsidies, above all to transportation and related uses, rose from 0.4 percent to 5.0 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2020—an increase of 4.6 percent of GDP.

- Transfer payments to persons enormously increased from 14.4 percent to 28.1 percent of GDP—an increase of 13.7 percent of GDP. Payments to individuals accounted for the vast majority of the increase in government spending and were overwhelmingly used for consumption.

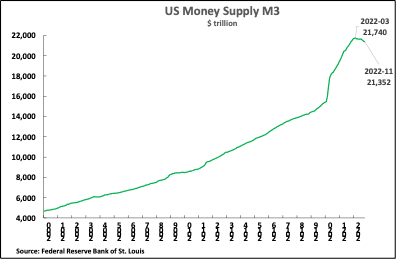

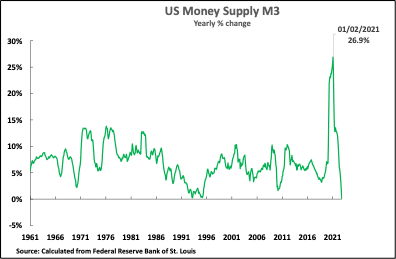

U.S. money supply The huge increase in consumer-focused government transfer payments was in turn accompanied by extremely rapid expansion of the U.S. money supply. Figure 8 shows that in the year to February 2021 the U.S. broad money supply rose by 26.9 percent—by far the most rapid increase in U.S. peacetime history. |

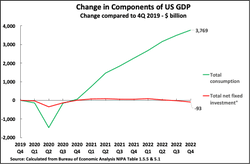

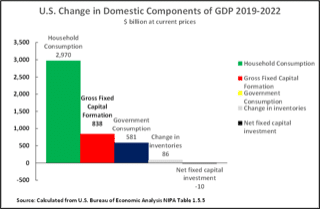

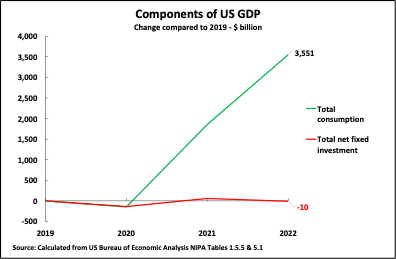

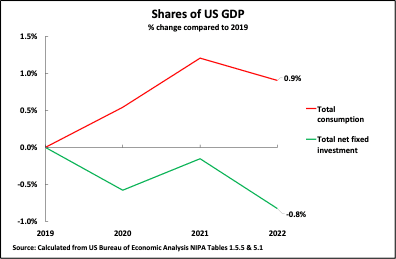

What occurred in the U.S. economy during its stimulus packages? Turning to the impact of these consumer-focused stimulus programs on the U.S. economy, Figure 9 shows the key changes in structure of U.S. GDP during the pandemic—that is, the changes from 2019, prior to the pandemic, to 2022. U.S. consumption rose relatively strongly by $3,551 billion. |

The final outcome of the U.S. stimulus packages

- Strategically the stimulus program was a complete failure—in the short term the inflationary wave forced the introduction of contractionary measures sharply slowing the U.S. economy in 2023, while in the medium/long term annual average the U.S. economic growth actually declined.

Part 2. Confusion of Supply and Demand: Why the U.S. Stimulus Packages Failed

- Confusions in U.S. economic thinking.

- The point in the business cycle at which this consumer-based stimulus was launched.

Confusions in U.S. economic thinking

The most important confusion in popular, more precisely “vulgar,” writing in Western economics is a fundamental and damaging confusion between the economy’s demand side and its supply side. This was used to create a false rationale for the U.S. stimulus packages, with their damaging consequences, and it unfortunately also sometimes appears in sections of China’s media. It is therefore important to clarify this.

This confusion between the economy’s demand and supply sides necessarily fails to understand the different roles played by consumption and investment in the economy, and therefore to an erroneous view that consumption can substitute for investment in terms of economic growth. To be precise:

- Considering first investment, this constitutes part of both the economy’s demand and supply sides. Investment goods and services appear in the economy’s demand side by being purchased (buying of machines, factories etc.) but they are also an input into production together with other factors such as labor—i.e., investment is part not only of the economy’s demand side but also part of its supply side. An increase in expenditure on investment is therefore not only an increase in demand but also an increase in supply—for example, if there is a purchase of a billion yuan of investment goods (machines etc.) there is also automatically a billion yuan increase in overall supply in the economy.

- In contrast to investment, consumption is only a category on the economy’s demand side, it does not appear in the economy’s supply side. This is necessarily the case because, by definition, consumption is not an input into production—if anything is an input into production it is not consumption. Therefore, for example, if there is a billion yuan increase in consumption there is a billion yuan increase in the demand side of the economy, but not any automatic increase in the economy’s supply side. An increase in consumption increases the demand side of the economy but, unlike with investment, it does not automatically increase supply.

Confusion over this fundamental theoretical issue, as will be seen, significantly explains the strategic failure of the U.S. stimulus packages.

A technical note

It is unnecessary here to discuss the differences between these concepts in “Western” and Marxist economic as both agree that investment (capital) is an input into production and therefore part of the economy’s supply side, but neither includes consumption as an input into production—and therefore in both consumption is only part of the economy’s demand side but not of its supply side. Put in technical language, consumption is not an input into the production function—but for non-economists it is sufficient to understand that consumption is not part of the economy’s supply side.

As a result of investment being part of both the economy’s demand side and its supply side, but consumption being only part of the economy’s demand side, if there is an increase in investment demand, that is there is an increase in real expenditure on investment, there is also a direct increase in the economy’s supply side. However, if consumption is increased there is an increase in demand but not any direct increase in supply.

Under certain circumstances, analyzed below, an increase in demand caused by increasing consumption expenditure, may indirectly lead to an increase in production—but this is not at all automatic and also under other circumstances, because consumption is not an input into production, an increase in consumption demand may not lead even indirectly lead to an increase in production. In some circumstances an increase in consumption expenditure may simply create inflation, suck in imports, or both without an increase in production. But in all cases, any increase in output can only occur if there is an increase in the economy’s supply side (that is in labor, capital etc.). Consumption itself provides no input into production and no increase in productive capacity.

The confusions in vulgar Western economic thinking

This confusion over demand and supply sides of the economy, and therefore over the role of consumption and investment, then follows directly from statements such as “With consumption accounting for 67 percent of GDP growth.” If both consumption and investment are an input into production this suggests then one can replace the other. For example, if consumption and investment are both inputs into production, and therefore both are parts of the economy’s supply side, perhaps consumption could be increased to 80 percent of GDP, and investment reduced to 20 percent, and production growth would continue as before? But this is entirely false.

If consumption were increased from 67 percent of GDP to 80 percent, and total GDP remained the same, then certainly total demand would remain the same—because both consumption and investment are sources of demand. Total demand would remain the same, and simply its division between consumption and investment would change. But if investment were reduced from 33 percent of GDP to 20 percent, because consumption had been raised from 67 percent of the economy to 80 percent, then the inputs into production would have been radically reduced. And because inputs into production had been radically reduced then, other things remaining equal, the increase in GDP would be radically slowed. That is, consumption cannot substitute for investment in production, because consumption is not an input into production.

This is why, for clarity of thinking and policy making, it is necessary to entirely eliminate such statements as “consumption contributed 67 percent of GDP growth”—consumption always contributes zero percent of GDP increase. This confusion between the economy’s demand side and its supply side provided the economic rationale for the damaging consumer, that is demand side only, U.S. stimulus programs.

The aim is consumption, but the means is investment