|

12/28/2022 Environmental struggles in the Chilean Global South: a matter of class and global inequalities By: Camilo Godoy PichonRead NowLast years we have seen many environmental struggles in Latin America: from the Bolsonaro’s illegal mining to mapuche people in Chile and Argentina or the Yagan people against colonialist expansion of salmon farming in the same countries. This is not only a matter of being “green” or an emotional approach, but in the Global South (understood not only as the so called Third World’ , but also for the excluded places in the Global North) every struggle has some extra component: the indigenous or local people fight against the capitalist expansion and the destruction of nature, but also with the subordination of these regions to the Global North interests or needs. It has been seen recently by Elon Musk's attempt to justify the bolivian coup towards Evo Morales in 2019 (“we coup whoever we want. Deal with it!”). According to the Argentinian author Julio Sevares, Chile is the most commodity-dependent country in Latin America. This started with the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet and its attempt to transform the whole country into a store for the needs of the big corporations. Chilean forestry has been thought of as an export to the US, China and Japan, as same as mining. Even lithium mining, which Chile is one of the most important owners in the world has been kept legally -and also by the “social democratic” current government of Gabriel Boric- with an ambivalent intervention of the state and the clear policy of not industrialising, for not teasing big countries. Chicago Boys’ doctrine was to develop a country based merely on commodities, which has been destroying our lands, lakes, animals and local communities during recent years. In this last case, in 2019 we saw how our little country was ‘invaded’ by some Scandinavian attempts to expand salmon farming to the Sub Antarctic region of Chile and Argentina. This event, with the miserable reunions from both ex Presidents Sebastian Pinera and Mauricio Macri with the Norwegian Kings, implied a serious threat for national sovereignty, for the communities and for the ecosystem. This wasn’t a matter only about Macri and Pinera’s agenda: this means how the countries from the Global North keep seeing Latin America as their backyard and the resources provider. Because salmon farming in Chile does not have the same standards as it does in Norway: in Chile we had the most amount of antibiotics in salmon and a serious damage to the sea due to these immense pools with salmon, existing in southern Chile. Cardenas (2019) has said that 98% of Chilean salmon goes to export. So this is clear evidence that current global capitalism looks to maintain the global inequalities at the same time it destroys our lands, our forests and animals, and especially threatens local sovereignty. In that sense, greenwashing is the closest thing to what Marx identified as “ideology”: these commodity companies present themselves as environment-friendly and look for the validation of the global capital, with the cost of extracting and provoking contamination, which will not be seen from the consumers of the Global North that take what we produce. A little of hope appeared from the organized local people of Ushuaia and Puerto Williams, where in the first city they made the historical triumph to suppress all salmon farming from its territory, after Macri’s attempt to expand it and take it there for the first time. These people understood that you cannot dissociate class from environmental conflicts and that the sovereignties and destinies of our peoples will prevail if we confrontate the global structure that puts us in a second place. The interesting thing about this is that whatever Norway does internationally (bombing Libya or destroying Chilean ecosystem for example), they will keep being considered a “sustainable state,” and Scandinavian countries, perceived as an example for the rest of the world. This, while our people fight and even die, because of how neoliberal globalization functions. AuthorCamilo Godoy Pichon is a chilean sociologist from the University of Chile and MA candidate in International Studies in University of Santiago, Chile. He has worked on topics such as environmental struggles and conflicts in the Global South, in regards to companies or corporations who promote extractivism and ecocide. He has worked with indigenous people, elders, and children from poor towns and areas from his country, along with developing academic work and research on the environmental justice' topic. He is very interested in analyzing how class influences environmental conflicts and other inequalities in South America and specially in neoliberal countries such as Chile. He has published 2 social/political poetry books both in Chile (2019) and Argentina (2022) and another poetry book on political repression during Pinochet's dictatorship, for the case of poor youngsters killed by the police in Southern Santiago in 1973, which will be published in Spain in early 2023. Archives December 2022

0 Comments

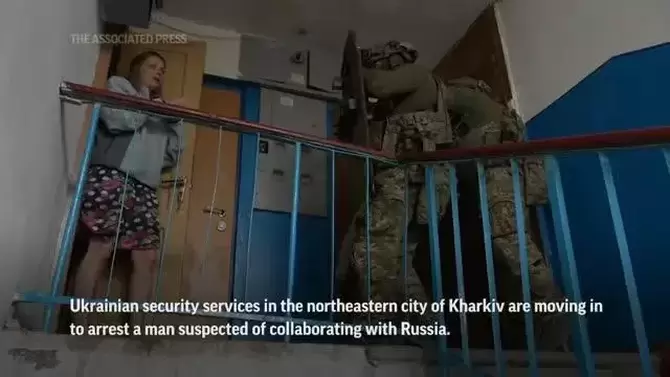

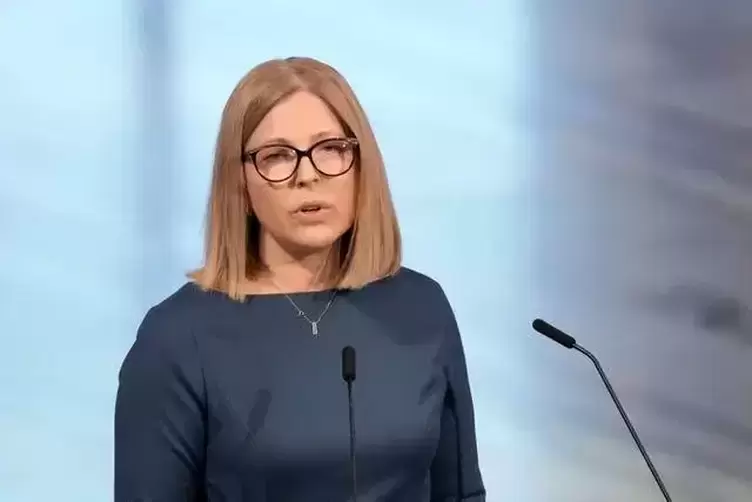

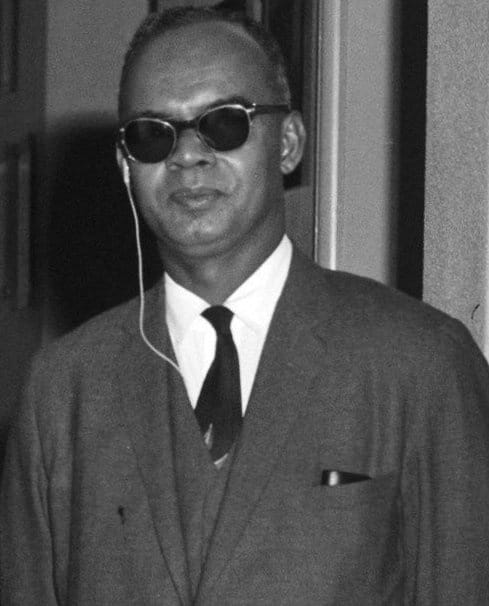

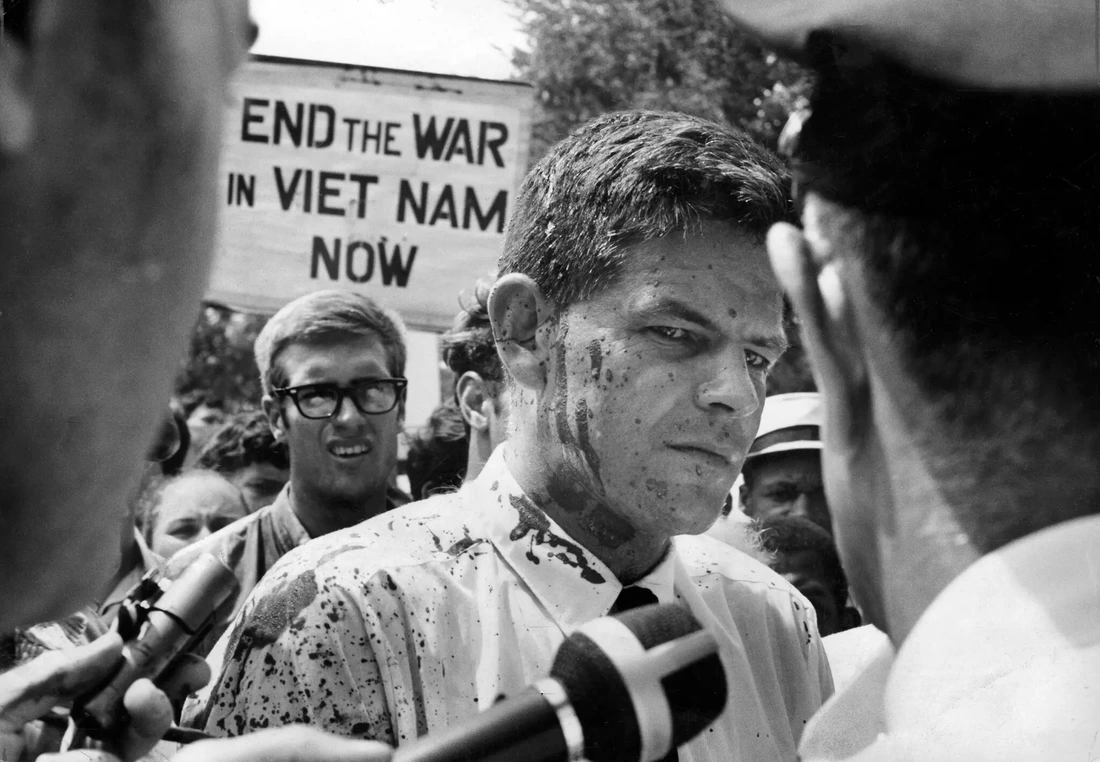

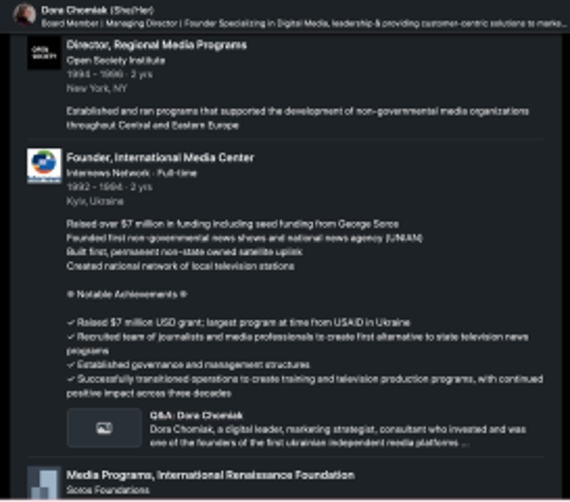

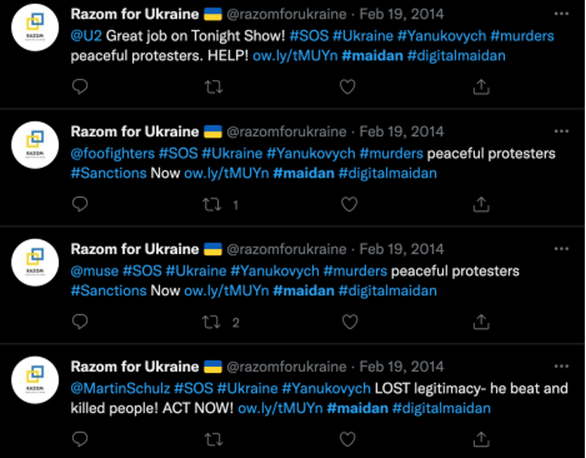

“Medicare is a pillar of the healthcare system” AFL-CIO June 13, 2022 Such a statement from the AFL-CIO would suggest that labor is determined to protect Medicare and even support improving and expanding it to all Americans. Additionally, President Biden and Democrats regularly criticize Republican threats to reauthorize and voucherize Medicare. Meanwhile, what’s left out of both the Democrat talking points and the AFL-CIO’s 2022 national resolution on healthcare is any acknowledgement that the real threat to Medicare and healthcare today is the decades’-long tax subsidized privatization supported by both major parties. With major support from organized labor, including AFL-CIO President George Meany at the signing, Medicare was signed into law in 1965. Before Medicare, only 60% of those over 65 had insurance since it was unavailable or unaffordable via private insurance (seniors were charged 3x the rate of younger people). Not only economically beneficial to the working class, the passage of Medicare was a huge civil rights victory as payments to physicians, hospitals, and health care providers were conditional on desegregation. While a big victory, Medicare did not provide full coverage for all services, and from its inception, there has been a drive to privatize and hand it over to profiteers. In fact, 2022 marks the 50th anniversary (1972) of Medicare permitting private insurance companies (HMOs) to participate in Medicare. President Clinton finalized HMO participation with Congress in 1997, and in 2003, the Medicare Modernization Act, under President Bush, further boosted privatization. The year 2003 marks the beginning of Medicare Advantage plans: insurance companies essentially masquerading as Medicare. HMOs and all the other private insurance companies introduced into Medicare after 1997 have not saved the government money, but instead, raised the cost to taxpayers much more than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. In 2005 the Government Accounting Office reported that “It is largely . . . excess payments, not managed care efficiencies, that enable plans to attract beneficiaries by offering a benefit package that is more comprehensive than the one available to FFS beneficiaries, while charging modest or no premiums. Nearly all of the 210 plans in our study received payments in 1998 that exceeded expected FFS costs….” Under traditional Medicare, patients can go to any doctor or provider that accepts Medicare without prior authorization or restrictive networks. With privatization, profits ensue as additional restrictions are imposed, such as narrow networks, micro-managing physicians, and prior authorizations. Routine denials of care are also a common practice forcing patients into lengthy appeals with the insurers betting many will walk away. In NYC, retirees have had to file lawsuits to stop their own leaders from changing their coverage from traditional Medicare with a supplement to a Medicare Advantage plan. These wasted tax dollars and huge profits for Medicare Advantage have skyrocketed over the years and contribute to draining the Medicare Trust Fund that supports all beneficiaries. While traditional Medicare has administrative costs of about 2%, the 10 private insurance companies that account for 80% of enrollees in Medicare Advantage have expenses of 15% including profits and advertising. The most recent Federal audits show that eight of the 10 largest Medicare Advantage companies have submitted inflated bills, and four out of five of the very largest have faced federal lawsuits with accusations of fraud. In 2020 alone, they exaggerated risk scores of patients and generated $12 billion in overpayments. Labor Supports ACA - Vehicle For Privatization With the passage of the ACA in 2010, the private insurance industry's role as a taxpayer subsidized vehicle for the healthcare delivery system was cemented and momentum for an alternative approach was stymied. Despite 600 union endorsements for Medicare for All Bill HR 676, union leaders joined Democrats to cheer the ACA as a resounding success. Inserted into the passage of the ACA was language that created a new agency, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation under the Center for Medicare Services (CMS). Labeled as an office of “innovation,” it has been given the authority to establish “pilot projects” that hand traditional Medicare to corporations. These “pilots,” established under the Trump administration and continued seamlessly by President Biden, accelerate the privatization and are even more insidious. Now called ACO REACH (Accountable Care Organizations, Reaching Equity, Access and Community Health), this program auto enrolls beneficiaries who have selected traditional Medicare into a privatized program without their consent. These programs can be eligible for profits of 25 to 40 percent. The aim of CMS is to put all beneficiaries into a privatized plan by 2030. Incredibly, it has no congressional oversight and little pushback by Congress. Top Labor Complicit as Biden Continues to Privatize Why Should the Rank-and-File Care? Even as labor negotiations continue to be inhibited by rising healthcare costs, labor refuses to expose the corruption and waste within the ongoing privatization of Medicare, harming its members, reducing union credibility, and contributing to the downward spiral of health benefits for all. The promotion of an official AFL-CIO Medicare Advantage plan and a do-nothing attitude towards ACO REACH must end. The Alliance for Retired Americans, the AFL-CIO’s national retiree organization, has refused to issue any statement against the privatization of traditional Medicare. Activists around the country are reporting that they are being cautioned to not call for the cancellation of the ACO REACH privatization program. What we are facing in 2022 is the destruction of Medicare by corporate privatization, supported by many top labor unions and their compromised “allies” in Washington. For comparison sake, take a look at labor in Canada where the top five health care unions are taking a stand to warn the public that the government in Ontario is intentionally creating a healthcare crisis to justify privatization, just like in the U.S. What Kind of Labor Movement Will Lead This Fight? There is ample reason for hope. A budding bottom-up movement has already garnered signatures from over 250 organizations in a letter sent to Health and Human Services Secretary Becerra asking him to end the ACO REACH privatization program. Included were the Alameda County, CA and Austin, TX Central Labor Councils plus the state AFL-CIOs in Vermont, Maine, Washington, and Kentucky and other labor groups. There have also been resolutions passed against ACO REACH by the Seattle City Council, West Virginia Democratic Party and the Texas State Democratic Executive Committee. Labor has the resources and organizational strength to lead this battle. It needs to multiply these actions tenfold to grow a real movement on behalf of working people everywhere. These efforts accompany a broader movement for healthcare justice spanning beyond retirees which include recent referendums in counties in rural Wisconsin and parts of Illinois calling for a national healthcare program as well as supermajority support in the US for Medicare for All. We need to be clear that change cannot be achieved without a sea change in the ideological direction of labor. Discussions and debates inside labor unions and among workers about the best strategies and tactics to tackle the corporate assault on public need are necessary. It’s clear that the current approach is not working. People are looking for answers that protect and advance the public interest. For unions to assume their proper role they must discard the petty, bureaucratic, and ossified approach of business unionism: a losing strategy which at its core is the “partnership” with corporations and a futile lobbying approach tied to the Democrats. It cannot meet the possibilities and needs of the day. Labor needs to stop providing cover for the privatization of Medicare and join the fight to end ACO REACH. We must mobilize a broad independent movement that unites all for the public interest. It’s only the power of the people that can win this. AuthorEd Grystar has more than 40 years experience in the labor and healthcare justice movements. He is co-founder and current chair of the Western Pennsylvania Coalition for Single Payer Healthcare and is a steering committee member of National Single Payer. Served as the President of the Butler County (PA) United Labor Council for 15 years. Has decades of experience organizing and negotiating contracts for health care employees with the Service Employees International Union and the Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses & Allied Professionals. Archives December 2022 2022 Nobel Peace Prize recipients all have connections to the NED, a CIA offshoot. [Source: spring96.org] Far-fetched as it sounds, this year’s winners are all connected to a CIA offshoot, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and parroted CIA / State Department / Pentagon talking points about Ukraine and Russia in their acceptance speeches he Nobel Prize Committee has five judges, appointed by the Norwegian parliament, who are tasked with choosing Nobel Prizewinners. But people are starting to wonder if there is a 6th Nobel Prize judge, not appointed by the Norwegian parliament, but by the CIA, who is tasked with making sure that winners of the coveted Nobel Peace Prize advance the agenda of U.S. policy makers. Although the idea may seem far-fetched, this year’s winners all have connections to a CIA offshoot, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Oleksandra Matviichuk, for example, who accepted this year’s Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the Ukraine Center for Civil Liberties (CCL) on December 10, had received the NED’s annual Democracy Award on behalf of the CCL six months earlier.[1] Senator Jim Risch (R-ID) presents the 2022 NED Democracy Award to Oleksandra Matviichuk of the Center for Civil Liberties, which also won the Nobel Peace Prize. [Source: ned.org] The NED was founded in the 1980s to promote propaganda and regime-change operations in the service of U.S. imperial interests. Allen Weinstein, the director of the research study that led to creation of the NED remarked in 1991: “A lot of what we do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA.” The two other recipients of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, Ales Bialiatski, a Belarusian dissident, and Memorial, a human rights organization expelled from Russia for violating its foreign agent law, have also received NED awards and probable financing. While the Nobel Peace Prize has previously gone to warmongers like Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Kissinger and Barack Obama,[2] never before has it gone to organizations that were intricately associated with a foreign intelligence agency specializing in political skullduggery and psychological warfare. The entire Nobel Peace Prize ceremony this year seemed to be part of a public relations spectacle whose purpose was to mobilize public opinion against Russia and to support a military escalation of the war in Ukraine. In their victory speeches, all three Peace Prize recipients ritually denounced Russian war crimes and aggression and issued support for the war in Ukraine. Oleksandra Matviichuk also directly asked the Norwegian government for more air defense for Ukraine and other types of weapons. Matviichuk is in the lower left. [Source: covertactionmagazine.com] Promoting a Fairy Tale Version of Reality Matviichuk’s speech was notable for its overt Russophobia and Manichaean view of world affairs that showed a fundamental naiveté about the character of Western governments. Matviichuk said that the West had turned a blind eye to Russia’s “destruction of its own civil society,” and “shook hands with the Russian leadership, built gas pipelines and conducted business as usual” when, for decades, “Russian troops had been committing crimes in different countries.” Oleksandra Matviichuk delivering Nobel Peace Prize address in Oslo, Norway, on December 10, 2022. [Source: arkansasonline.com] In Matviichuk’s telling, the “innocent” West is complicit in appeasing Russia—though for the last few decades, it was U.S. troops and its proxies that rampaged across the Middle East and committed massive war crimes. All while Russia has often intervened in self-defense against U.S.-NATO aggression—like in Georgia in 2008—or at the request of a besieged ally, like in Syria, where it saved the country from the fate of Libya which had been destroyed by the 2011 U.S.-NATO intervention. Matviichuk claimed in her speech that the war in Ukraine is “not a war of two states—but of two systems—authoritarianism and democracy.” If that is the case, it is not clear which side she is on as her president, Volodymyr Zelensky, has banned eleven opposition parties, including the communist party, which is legal in Russia, and mounted a Phoenix-style operation to silence dissidents. [Source: covertactionmagazine.com] Matviichuk suggested earlier in her speech that the world had not adequately responded to “the act of aggression and annexation of Crimea, which were the first such cases in post-war Europe.” Crimea, however, had historically been part of Russia and was never invaded. Its people voted to rejoin Russia in a referendum after the U.S. and EU had backed a right-wing coup in Ukraine that represented a vital security threat to Russia on its border. Matviichuk presented more false history when she claimed that “the Russian people were responsible for this disgraceful chapter in their history [the invasion of Ukraine] and their desire to forcefully restore their former empire.” Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine, however, was not an attempt to restore the Russian empire, but was carried out in response to genuine national security threats that Russia faced as a result of the right-wing coup in Ukraine and NATO advancement on its border. Matviichuk further omits that Russia was carrying out a genuine humanitarian intervention by trying to save the people of eastern Ukraine who had been the target of an ethnic-cleansing operation by the Ukrainian military, which left 14,000 civilians dead. Matviichuk concluded part of her speech by stating: “People of Ukraine want peace more than anyone else in the world. But peace cannot be reached by the country under attack laying down its arms. This would not be peace, but occupation. After the liberation of Bucha, we found a lot of civilians murdered in the streets and courtyards of their homes. These people were unarmed. We must stop pretending deferred military threats are ‘political compromises.’ The democratic world has grown accustomed to making concessions to dictatorships. And that is why the willingness of the Ukrainian people to resist Russian imperialism is so important. We will not leave people in the occupied territories to be killed and tortured. People’s lives cannot be a ‘political compromise.’ Fighting for peace does not not mean yielding to pressure of the aggressor, it means protecting people from its cruelty.” The Nobel Peace Prize recipient in Oslo at a press conference with the Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre (to her left), from whom she asked to provide her country with more weapons! [Source: ccl.org.ua] It is astounding that someone would use the platform accorded to her by winning a major world peace prize to try to rationalize a war that her country had started—in 2014 when it attacked the people of eastern Ukraine who voted for more autonomy after a foreign-backed coup in Ukraine, and after the post-coup government imposed draconian language laws.[3] Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko (2014-2019) has even disclosed that Ukraine had no intention of abiding by the Minsk peace agreements, which could have prevented a full-scale conflict with Russia. Instead, Ukraine signed those agreements as a stalling tactic to give it more time to build up its military power and accrue more weaponry and support from the U.S. so it could fight Russia from a position of strength. Matviichuk promoted more disinformation by suggesting that the Russians had killed all the civilians in Bucha, as in-depth investigations have determined that many civilians were killed in Bucha by the Ukrainians after Russian forces were expelled. Her true political colors were seen at the end of the speech when she praised the “people in Iran fighting in the streets for their freedom,” and people in China who were resisting its “digital dictatorship.” This is right out of the playbook of the NED, which sponsors organizations that denounce human rights abuses of independent countries targeted by the U.S. for regime change, while extolling the heroism of dissidents who would align their country with the U.S. Shades of Obama 2009 Matviichuk’s use of the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony as a forum to promote war drew on the precedent established by the drone king, Barack Obama, when he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009. In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Obama provided a tortured defense of U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, stating “we must begin by acknowledging the hard truth that we will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes. There will be times when nations—acting individually or in concert—will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified.” Obama continued: “I make this statement mindful of what Martin Luther King said in this same ceremony years ago—‘violence never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: It merely creates new and more complicated ones.’ As someone who stands here as a direct consequence of Dr. King’s life’s work, I am living testimony to the moral force of non-violence. I know there is nothing weak—nothing passive—nothing naïve—in the creed and lives of Gandhi and King. But as a head of state sworn to protect and defend my nation, I cannot be guided by their examples alone. I face the world as it is, and cannot stand idle in the face of threats to the American people. For make no mistake: Evil does exist in the world. A non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler’s armies. Negotiations cannot convince al-Qaeda’s leaders to lay down their arms. To say that force is sometimes necessary is not a call to cynicism—it is a recognition of history; the imperfections of man and the limits of reason.” Barack Obama, the drone king and a prolific killer by his own admission, giving Nobel Peace Prize speech in which he gave a torturous defense of the criminal U.S. wars of aggression in the Middle East. [Source: bydewey.com] Honoring a Propaganda Agency That May Well Help Ignite World War III While the Nobel Peace Prize has not always honored true peace activists, a truly ominous precedent has been set in giving it to a propaganda agency that may well help ignite World War III. A key part of CCL’s current mission is to document Russian war crimes in Donbas—though Ukraine has been responsible for the majority of human rights crimes there since the war started after the U.S.-backed coup in 2014—when CCL started this work.[4] Residents from towns in eastern Ukraine have reported on widespread rapes and torture of captured prisoners by Ukrainian troops and constant shelling of civilian centers and terror bombing over an eight-year period. This is ignored by the CCL, which instead has tried to spotlight the stories—real or imagined—of victims of sexual violence by Russian troops in Ukraine and women abducted by Russian troops and taken into captivity in Russia. Further, the CCL has mounted an international campaign to release the Kremlin’s political prisoners, and aims to raise awareness about political persecution in what it calls Russian-occupied Crimea—which is not “occupied” since its people voted to rejoin Russia in a referendum. CCL staffers with yellow vests out to investigate Russian war crimes. [Source: ned.org] The CCL fashions itself as a particular champion of the Crimean Tatars, some of whom had collaborated with Nazi Germany in World War II and who had long been used by outside powers to try to destabilize Russia and foment ethnic conflict as part of a strategy of divide and conquer. Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev, who received an award from the NED in 2018, travelled to the NATO headquarters in Brussels after the Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014 agitating for an armed intervention by the UN to return Crimea to Ukrainian control, and has been a militant proponent of sanctions against Russia. NED Director Carl Gershman awarding Mustafa Dzhemilev with Democracy Service Medal. [Source: ned.org] Matviichuk is co-author of the study, “The Fear Peninsula: Chronicles of Occupation and Violations of Human Rights in Crimea,” a one-sided propaganda pamphlet aimed at mobilizing public opinion in support of Ukraine’s efforts to reconquer Crimea—against the wishes of its people. Belarusian Winner Also Has NED Connection

NED-backed color revolution in Belarus in 2020-2021 where protesters waved pre-revolutionary era flags. [Source: counterpunch.org] Lukashenko is a close ally of Vladimir Putin who has supported strengthening the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), an alliance of Eurasian countries promoting trade in national currencies instead of the U.S. dollar and regional economic integration as a means of presenting a strong united front against U.S. imperialism. Alexander Lukashenko and Vladimir Putin—two targets of American regime change. [Source: timesunion.com] Bialiatski’s wife, Natalia Pinchuk, who received the Nobel Peace Prize on his behalf, used the opportunity to falsely denigrate Lukashenko for heading a “dependent dictatorship,” which she said Putin also wanted to impose on Ukraine. Pinchuk further condemned Lukashenko for “choosing to engage with society through the use of force—grenades, batons, stun guns, endless arrests and torture.” Natalia Pinchuk in Nobel Peace Prize speech. [Source: heraldseries.co.uk] These latter words hold some truth, though leaders throughout the world would react the same way as Lukashenko in the face of a foreign backed uprising, whose main purpose was to destroy Belarus’s successful socialist experiment and transform the country into another proxy of the U.S. and NATO that could be used as a staging ground for destabilizing Russia. Bialiatski significantly was a panelist at a 2014 NED forum where he spoke alongside long-time NED Director and neo-conservative ideologue Carl Gershman. (See photo below.) Ales Bialiatski (far right) appeared on a panel with NED Founding President Carl Gershman (far left) at the Forum 2000 Conference in 2014. [Source: ned.org] This indicates probable NED funding for the organization that Bialiatski established--Viasna—whose purpose has been to monitor human rights abuses committed by the Lukashenko government and to advocate for anti-regime dissidents.

Yet Another NED Connection The third winner of this year’s Nobel Peaze Price is a banned Russian human rights organization, Memorial, whose work includes preserving the memory of the victims of Soviet gulags and Joseph Stalin’s reign, and documenting political repression and human rights violations in Russia.[6] In 2004, its director, Arseny Roginsky, was awarded the 2004 NED Democracy Award. Arseny Roginsky (center) poses with other awardees from Russia during the 2004 Democracy Awards ceremony. [Source: ned.org] This latter award suggests that Memorial--founded by Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov during perestroika in the 1980s—received financing from the NED, which was very generous in Russia toward civil society groups whose agenda was to denigrate the Soviet system and undermine Putin, who helped take back national control of Russia’s economy following a period of looting and Western exploitation under Boris Yeltsin. In 2014, Memorial was in fact placed on a list of foreign agents by the Russian government, which suspected it of receiving foreign funding. Shuttered office of Memorial after Russian authorities closed it for violating the 2012 foreign agent law. [Source: bbc.com] Should It Be Renamed the Nobel War Prize?The Nobel Peace Prize has tarnished its reputation through many of its past selections; but this year seems worse then ever with the Nobel ceremony providing a platform for anti-Russia war incitement. In the future, all pretenses should be thrown aside and the prize finally renamed the Nobel War Prize. Whereas at one time genuine peace activists—like Emily Greene Balch, Linus Pauling and Martin Luther King, Jr.—were awarded the prize, now it is being conferred on war propagandists and national traitors in the pay of foreign masters who are using them merely as pawns in a deadly game in which there are no winners.

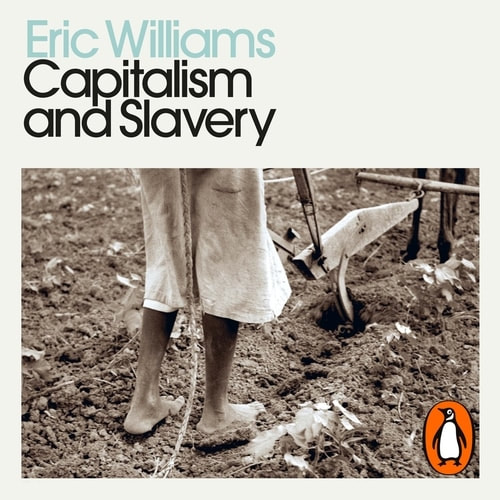

AuthorJeremy Kuzmarov is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine. He is the author of four books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019) and The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018). He can be reached at: [email protected]. This article was republished from CovertAction Magazine. Archives December 2022 12/27/2022 South Africans Are Fighting for Crumbs: A Conversation With Trade Union Leader Irvin Jim By: Vijay Prashad & Zoe AlexandraRead NowIn mid-December, the African National Congress (ANC) held its national conference where South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa was reelected as leader of his party, which means that he will lead the ANC into the 2024 general elections. A few delegates at the Johannesburg Expo Center in Nasrec, Gauteng—where the party conference was held—shouted at Ramaphosa asking him to resign because of a scandal called Farmgate (Ramaphosa survived a parliamentary vote against his impeachment following the scandal). Irvin Jim, the general secretary of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA), told us that his country “is sitting on a tinderbox.” A series of crises are wracking South Africa presently: an unemployment crisis, an electricity crisis, and a crisis of xenophobia. The context behind the ANC national conference is stark. “The situation is brutal and harsh,” Irvin Jim said. “The social illness that people experience each day is terrible. The rate of crime has become very high. The gender-based violence experienced by women is very high. The statistics show us that basically people are fighting for crumbs.” At the ANC conference, five of the top seven posts—from the president to treasurer general--went to Ramaphosa’s supporters. With the Ramaphosa team in place, and with Ramaphosa himself to be the presidential candidate in 2024, it is unlikely that the ANC will propose dramatic changes to its policy orientation or provide a new outlook for the country’s future to the South African people. The ANC has governed the country for almost 30 years beginning in 1994 after apartheid ended, and the party has won a commanding 62.65 percent of the total vote share since then before the 2014 general elections. In the last general election in 2019, Ramaphosa won with 57.5 percent of the vote, still ahead of any of its opponents. This grip on electoral power has created a sense of complacency in the upper ranks of the ANC. However, at the grassroots, there is anxiety. In the municipal elections of 2021, the ANC support fell below 50 percent for the first time. A national opinion poll in August 2022 showed that the ANC would get 42 percent of the vote in the 2024 elections if they were held then. Negotiated Settlement Irvin Jim is no stranger to the ANC. Born in South Africa’s Eastern Cape in 1968, Jim threw himself into the anti-apartheid movement as a young man. Forced by poverty to leave his education, he worked at Firestone Tire in Port Elizabeth. In 1991, Jim became a NUMSA union shop steward. As part of the communist movement and the ANC, Jim observed that the new government led by former South African President Nelson Mandela agreed to a “negotiated settlement” with the old apartheid elite. This “settlement,” Irvin Jim argued, “left intact the structure of white monopoly capital,” which included their private ownership of the country’s minerals and energy as well as finance. The South African Reserve Bank committed itself, he told us, “to protect the value of white wealth.” In the new South Africa, he said, “Africans can go to the beach. They can take their children to the school of their choice. They can choose where to live. But access to these rights is determined by their economic position in society. If you have no access to economic power, then you have none of these liberties.” In 1996, the ANC did make changes to the economic structure, but without harming the “negotiated settlement.” The policy known as GEAR (Growth, Employment, and Redistribution) created growth for the owners of wealth, but failed to create a long-term process of employment and redistribution. Due to the ANC’s failure to address the problem of unemployment--catastrophically the unemployment rate was 63.9 percent during the first quarter of 2022 for those between the ages of 15 and 24—the social distress being faced by South Africans has further been aggravated. The ANC, Irvin Jim said, “has exposed the country to serious vulnerability.” Solidarity Not Hate Even if the ANC wins less than 50 percent of the vote in the next general elections, it will still be able to form a government since no other party will attract even comparable support (in the 2019 elections, the Democratic Alliance won merely 20.77 percent of the vote). Irvin Jim told us that there is a need for progressive forces in South Africa to fight and “revisit the negotiated settlement” and create a new policy outline for South Africa. The 2013 National Development Plan 2030 is a pale shadow of the kind of policy required to define South Africa’s future. “It barely talked about jobs,” Jim said. “The only jobs it talked about were window office cleaning and hairdressing. There was no drive to champion manufacturing and industrialization.” A new program—which would revitalize the freedom agenda in South Africa—must seek “economic power alongside political power,” said Jim. This means that “there is a genuine need to take ownership and control of all the commanding heights of the economy.” South Africa’s non-energy mineral reserves are estimated to be worth $2.4 trillion to $3 trillion. The country is the world’s largest producer of chrome, manganese, platinum, vanadium, and vermiculite, as well as one of the largest producers of gold, iron ore, and uranium. How a country with so much wealth can be so poor is answered by the lack of public control South Africa has over its metals and minerals. “South Africa needs to take public ownership of these minerals and metals, develop the processing of these through industrialization, and provide the benefits to the marginalized, landless, and dispossessed South Africans, most of whom are Black,” said Jim. No program like this will be taken seriously if the working class and the urban poor remain fragmented and powerless. Jim told us that his union—NUMSA—is working with others to link “shop floor struggles with community struggles,” the “employed with the unemployed,” and are building an atmosphere of “solidarity rather than the spirit of hate.” The answers for South Africa will have to come from these struggles, says the veteran trade union leader. “The people,” he said, “have to lead the leaders.” AuthorVijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives December 2022 12/21/2022 ‘Capitalism and Slavery’, and dismantling the accepted narratives of history By: John BurnsRead NowWhen British capitalism depended on the West Indies,” Eric Williams wrote in 1938, they ignored slavery or defended it. When British capitalism found the West Indian monopoly a nuisance, they destroyed West Indian slavery. Williams (Photo: Wikipedia) Williams had no time for sentimental views on the abolition of slavery. The history he dealt in was more honest, more straightforward, and unafraid to confront the accepted narratives, wherever these might be found. And confront he did. His 1945 work, Capitalism and Slavery, systematically destroyed the traditional, rose-tinted views of abolition in the UK, replacing the cozy and humanitarian with the cold and pragmatic, substituting empathy and egalitarianism with hard economic necessity. In Williams’s view, the United Kingdom reaped the immense benefits of slavery—for centuries, in fact—and dropped the practice only when it no longer served its lucrative purpose. To look at the facts in any other light is simply a pretense. There are voices of humanitarianism within Williams’s work. There are voices of empathy, of egalitarianism. There are people whose consciences are clear, who’s hearts are true, people who fought against slavery and the British Empire’s grim association with it. There are all of these things because there were all of these things in real life. These voices existed in Georgian and Victorian Britain, and so they are present in Williams’s writing. It’s just that these voices, these notes of discord, were lost in a far larger choir. Those making all the noise—those who truly influenced governors and policymakers—were motivated by very different factors, such as economics, geopolitics, imperialism, and capitalism. Williams received his early education in his native Trinidad and Tobago, then still part of the British Empire. As a student, he was awarded a scholarship to Oxford University, where he excelled as a student and refined many of ideas that would characterize his later work. In 1956, Williams formed the People’s National Movement (PNM), becoming the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago that same year, and eventually led the country to independence in 1962. He continued to serve at the helm of the new nation right up until his death in 1981 at age 69, in the nation’s capital, Port of Spain. His achievements as a freedom-minded politician and global head of state may have overshadowed his earlier work in academia, but these two aspects of his career cannot be separated. His clear-eyed and honest approach to history, and to his own people’s place within that history, shaped the path he would take in the following decades. By deconstructing UK attitudes to the slave trade, and its eventual abolition, Williams laid the foundations for dismantling British imperialism in the Caribbean. His contribution to our historical understanding, and to nationhood for Trinidad and Tobago, are inextricably linked. Williams’s ideas are not new anymore. Capitalism and Slavery was written largely as a doctoral thesis in 1938, refined and published in 1945, and has been discussed for decades since. But Penguin’s relaunch of the book in 2022 is the first mass-market edition of the work to hit the shelves in the United Kingdom. It has, deservedly, become a bestseller. But why does this matter now? Because we are still in danger of falling under the sway of accepted truths and fantastical narratives of history. The book is a timely reminder that history is a science that helps us better understand the culture and politics of our own age—it is not sculptor’s clay, ready to be molded into whatever shape or form best suits our own blinkered, and often prejudiced, aesthetic vision. History does not owe us anything. It is not ours to manipulate or distort. In June 2020, the statue of enslaver Edward Colston was toppled by demonstrators in Bristol—a city that appears again and again in the pages of Capitalism and Slavery, thanks largely to the profits from the trade in sugar and enslaved people that flowed across its docks. This trade was so lucrative that Bristol became the Crown’s “second city” until 1775. It was men like Colston who helped achieve this status—hence the statue. Colston had been, but his work as a merchant, slave trader, and subsequently, a Member of Parliament is etched into the stone upon which Bristol stands. He was almost three centuries dead by time his bronze likeness was lobbed into the Bristol Channel, and he likely had very little opinion on the matter. Fortunately for Colston, there were plenty of people in 2020 who did have opinions on the matter. History--their history—they cried, was being erased. The “armies of wokeness” and “politically correct groupthink” were destabilizing the proud heritage of the United Kingdom, they claimed. Sure, Colston traded in slaves, but it was a different time, and Colston was a great man—a true hero of the city and its people—not to mention the criminal damage, public order offenses, or the rights of the sculptor himself. This is an example of historical distortion and manipulation at work, pursuing ends that are nothing short of racist. History has provided us with a figure—Colston—whose great wealth led to the rise of one of the UK’s most important cities. History has provided us with the facts regarding the sources of that wealth—the slave trade; the theft of dignity from our fellow human beings. History does not provide us a way with which we can separate the two—we cannot have one without confronting the other. Erecting a statue to Colston--celebrating Colston for his efforts and his achievements—means erecting a statue to the slave trade, too. Nor does history provide us with icons who are beyond reproach. By searching history for unimpeachable icons—symbols of a particular set of values or ethics—we are destined only for failure. If, in response to our disappointment at finding flawed human beings in lieu of the pristine icons we seek, we resort to mythologizing and hagiography, we play a very dangerous game, indeed. In another of the twentieth century’s great social texts, Women, Race and Class, Angela Y. Davis examines the relationship between feminist heroes Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and the “women first, negroes last” policies of Democratic politician Henry Blackwell. Blackwell spoke in support of women’s suffrage in the South, asserting that “4,000,000 Southern women will counterbalance 4,000,000 negro men and women”, retaining the “political supremacy of the white race.” Davis writes about the “implicit assent” of Anthony and Stanton to Blackwell’s racist logic as she explores the troubling and complex nature of women’s suffrage during its gestation. Like Williams and his deconstruction of accepted beliefs regarding abolition, Davis’s analysis of racist attitudes in the women’s suffrage movement leads to an awkward confrontation. Stanton and Anthony made incredible contributions to the rights of women in the United States, and this should never be forgotten—but to turn a blind eye to the gross inequality that formed the backdrop to the movement is to deny this injustice altogether, leaving us with a flawed and incomplete understanding of our own history. This approach—this honesty, this meticulousness—is found within the pages of Capitalism and Slavery, too. This is not simply an attack on the white establishment of the United Kingdom and their forbears in the heyday of the empire; this is a methodical analysis of the key drivers behind the rise and fall of the British slave trade. Williams’s work is certainly not an attack on abolition—a critical moment in establishing of a better world for all human beings—but neither does it seek to perpetuate false ideas of who and what made the moment of abolition a reality. Two centuries before the slave trade reached its peak, the very concept of slavery was decried by the uppermost echelons of power in the British Empire. Queen Elizabeth I herself said that enslavement would “call down the vengeance of heaven,” and yet, by the eighteenth century, all sorts of mental gymnastics were deployed to justify the trade. Church leaders, Williams said, proposed that slavery could bring “benighted beings to the chance of salvation,” while conservative thinker Edmund Burke—himself a rigorous supporter of religion’s place in society—expounded on the slaveholder’s right to maintain ownership of “their property”, that is, the human beings they had paid for. It seems ethics and morality are not absolutes, and can be manipulated to support economic prosperity. When such leaps of logic and desperate justification can support the rise of the slave trade, why should these moral contortions suddenly cease? Why should the voices of humanity win the day, defeating the barbarism of trans-Atlantic slavery and achieving a resounding—if delayed—moral victory? The answer is simple: they didn’t. Williams foreshadows the eventual collapse of the trade by presenting the views of contemporary economists Josiah Tucker and Adam Smith, who declared the trade to be expensive and inefficient. In the end, it would be economics, not ethics, that would defeat the United Kingdom’s plantations and slave ships. If the going was good, the slave trade would continue, no matter how many horrific acts were perpetrated on the shores of Africa and on the islands of the Caribbean. When the market stopped being profitable—when the fiscal engine driving slavery forwards started to cough and sputter—the trade would cease. The laws of business and enterprise, as cold and inhuman as they are, were far stronger than any moral outrage. More than eight decades have gone by since Williams completed his doctoral thesis, and it is pleasant to think that we have moved on a great deal since those days. After all, Williams was then a subject of the British Empire. Now, the citizens of Trinidad and Tobago—along with the citizens of other former colonies—are free to determine their own path in the world. In 1965, the United Kingdom passed the Race Relations Act, outlawing discrimination on the “grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins”—a positive step towards a better, more welcoming nation. But we should not wrap ourselves too tightly in this comfortable blanket of pleasant thought. In 1968, three years after the Race Relations Act was passed, Enoch Powell made his rivers of blood speech in Birmingham. Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, division and discrimination led to violent flashpoints as riots ripped through urban centers. In 1993, the tragic murder of Stephen Lawrence exposed the systematic racism at the core of UK policing. In 2018, the so-called Windrush Scandal, overseen by then-Home Secretary Theresa May, saw immigrant UK citizens stripped of their rights and their dignity. The fight against discrimination and prejudice is far from over, and no amount of historical airbrushing can compensate for this. This is why Williams’s work is so relevant today: It reminds us to question the comforting and convenient narratives of accepted history. Twisting historical narratives to fit our own agenda—to reflect our own view of what Britain represents—is deceitful at best, and dangerous at worst. A more critical, clear-eyed, analytical approach to the past is necessary if we are to truly understand the challenges of the present. Sources: