|

We live in an age characterized by anxiety and anomie, on the one hand, and hatred and resentment on the other. While the former is a corollary of the hyper-individualizing tendencies inherent in our current economic regime, the latter is the result of right-wing politics. Firstly, neoliberal capitalism has deployed markets in two senses at once, simultaneously enforcing them as the sole rational basis for material distribution and expanding the reach of market-based valuation into non-market spheres as a cultural norm. This has severely eroded collective bases of solidarity, giving rise to social atomism. Secondly, the contemporary Right has molded these insecurities into what Arjun Appadurai has called “aspirational hatred” [1]. This refers to the redirection of aspirations away from better jobs, more economic security and greater social respectability towards a darker form of rising expectations, in which the new role models are the xenophobic leaders of populist movements. These leaders act as exemplars in the sublaterns’ life, allowing them to dwell in an imagery of empowerment through a discourse of ethno-national purity and cultural superiority. In other words, aspirations become tied to retributive actions against scapegoated identities. The combination of neoliberal policies on the economic front and neo-fascist actions on the politico-cultural front has certainly signaled a period of defeat for socialist movements. However, there has been little critical introspection on the part of the Left of its strategies and tactics. We have only seen a clamorous call to resist the fascist onslaught against the working class. Behind these urgent claims lies the failure to extricate oneself from the immediacy of what is happening; uncritical immersion in the material reality forecloses any possibility of carefully considering the roots of the Right’s resurgence and transcending the electoral exigencies of parliamentary politics. What the present-day moment demands is a sustained re-thinking of the ideological devices traditionally used by the Left. Rather than regarding the rise of the Right as an instance of mass irrationalism and peddling the unproductive narrative that the working class was “duped” by deceptive maneuvers, we need to locate the precise reasons which made the Left’s social constituency susceptible to (proto) fascist ideas. In particular, the Right’s use of emotion should not be seen as counterposed to the Left’s support for reason: emotions are part of our everyday reasoning, experience and relation to the world, because they are highly discerning commentaries about our concerns and commitments. Different emotions have different normative structures and analyzing these can tell us something about the situations in which they are produced. The centrality of emotions and subjective experience is also indicated by the fact that injustices of recognition and redistribution often only reveal themselves in the lived reality of social relations. Ellen Meiksins Wood made precisely this point when she used E. P. Thompson’s notion of experience against Althusserian definitions of class as an abstract structural location: “since people are never actually ‘assembled’ in classes, the determining pressure exerted by a mode of production in the formation of classes cannot be easily expressed without reference to something like a common experience - a lived experience of…the conflicts and struggles inherent in relations of exploitation” [2]. Further explorations into the political status of this subjective-emotional plane can help in the formation of new socialist ideas by delineating how the Right gained power through a molecular, bottom-up process of hegemony-formation. LAY NORMATIVITY In his book “The Moral Significance of Class”, Andrew Sayer writes about lay normativity i.e. people’s evaluative orientation, or relation of concern to the world around them. We are evaluative beings, continually monitoring and assessing our behavior and that of others, needing their approval and respect, but in contemporary society this takes place in the context of inequalities which affect both what we are able to do and how we are judged. Lay normativity is composed of moral judgments, treated not as a system of external, regulative norms/conventions but as based primarily on actors’ moral sentiments, which in turn are developed through social interaction. This feature derives from the fact that morality is serious, that is, about matters that affect people and their wellbeing deeply, whereas mere rules need not necessarily be serious (for example, ways of setting a table). Its seriousness derives from its significance for human well-being and is reflected in the expectation of some kind of justification for its codes. According to Sayer [3]: [T]he [moral] rationales are to be found within available discourses, but they are more than mere internalized and memorized bits of social scripts. Discourses derive from and relate to a wider range of situations than those directly experienced by the individuals who use them, thereby allowing them vicarious access to the world beyond them. While they constrain thought in certain ways, they are also open to different interpretations and uses, and endless innovation and deformation, and they tend to contain inconsistencies and contradictions, making them open to challenge from within. Although they structure perception they do not necessarily prevent identification of false claims; for example, just because someone believes that the social world is organized on a meritocratic basis, it does not mean that no experience could ever lead them to have doubts about this. In further developing the open-ended nature of lay normativity, Sayer critically engages with Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus - which refers to the set of dispositions that individuals acquire through socialization, and which orient them towards the social and physical world around them. In Bourdieu’s analysis, the dispositions characterizing a habitus are understood primarily as instrumental orientations to the requirements of occupying particular positions within a social field: by and large people acquire the necessary dispositions for them to function effectively within the social positions they occupy. This “emphasis on the adaptation of the habitus to actors’ circumstances,” Sayer argues, “exaggerates actors’ compliance with their position and makes resistance appear to be an anomalous form of behavior occasioned only by special circumstances” [4]. Sayer challenges this general “complicity between habitus and habitat” by arguing that human dispositions to act in various ways are not simply the result of structural conditioning but also of the “internal conversations” of “mundane reflexivity”, and these internal conversations help shape normative sensibilities [5]. Unlike instrumental dispositions which are tightly integrated with our class location, moral dispositions tend to have a relatively universalizing quality to them, particularly as mundane reflexivity interacts with the realities of suffering and flourishing. In the words of Sayer, these universalizing tendencies derive “from the reciprocal character of social relations, from their responsiveness to our human as well as our more specifically cultural being, and partly from experiences of good and bad treatment which are not reducible to effects of class and gender or other social divisions but cross-cut them.” [6] The existence of these universalistic tendencies is most powerfully indicated by “shame”. [7] In capitalist societies, the “social bases of respect” in terms of access to valued ways of living are unequally distributed, and therefore shame is likely to be endemic to the experience of subaltern classes. If there were not some degree of cross-class agreement on the valuation of ways of life and behavior, there would be little reason for class-related shame, or concern about respectability. The consequence is that moral dispositions can generate longings for a world at variance with the one we are living in. In a world marked by the relentless seduction of commodities, the glorification of educational advancement and economic success, the pressure to conform to gender norms and be popular, accompanied by economic insecurity, anomie, and loneliness, unfulfilled longings can be extremely powerful. These longings - while socially and culturally mediated by specific contexts - also have a more primitive basis than mere internalization of social influences. Humans are characterized not only by animal lack, as in hunger for food, but desire for recognition and self-respect, which they can only obtain through certain kinds of interactions with others. Taking into account the presence of longings, resistance, then, is not simply the result of exogenous and episodic dislocations of the social field but also of the inherent tensions between instrumental dispositions of the habitus and moral dispositions which are less socially localized in character. Insofar that lay normativity and public morality are partially structured beyond the limits of social positions, the universalizable dimension of moral frames themselves structure social conditions necessary for different kinds of politics. The Right harnessed the lay normativity of the neoliberal era - torn apart by anxiety, incoherent insecurity, persistent shame and delimited desires for change - to inaugurate a social psychology devoted to the exploitation of the excess of subjective proliferation that sustains on the objective context but refuses to be tied down to it. While the Left was busy emphasizing the instrumental-interest based logic of the working class, the Right was tapping into popular imagination by using and shaping emotions and passions. Singular emphasis by leftists on bare materiality or economic aspects of the problems faced by subalterns fared poorly in comparison to visceral and raw communication with the deeply felt sentiments of fear, gut instincts, anxiety, anomie and alienation. Again, the example of shame can be given to outline how the Right capitalized on the lay normativity of subalterns. We feel shame as a result of a failure to live up to norms, ideals, and standards that are primarily public. Because of this focus on a (dominant) group’s norms, minorities, lower classes, and marginalized groups are more vulnerable to experiencing shame and to being victims of shame practices. Shame has both a transformative and regressive potential. On the one hand, groups can be persistently stigmatized through shame within society. On the other, shame can be a powerful force in that it incites reactions against such shame practices. By turning the negative experience of shame into a positive feeling of uniting and coming into action, shame can provide groups with cultural and political agency. However, the Left’s insensitivity toward lived experience allowed neo-fascist politics to channelize shame in the direction of symbolically empowering actions against manufactured enemies. RE-ENVISIONING LEFT POLITICS As we have seen, lay normativity operates at the cutting edge of universalizing evaluative agreements. In fact, social positions are themselves, at times, made sense of through available moral frames that tend to hold more universal appeal. The Left was unable to engage with these subjective currents by almost exclusively focusing on and extrapolating from the habitus of sublaterns, thus in part essentializing working class identity. In the absence of a normatively convincing narrative about the future and sustained engagement with moral dispositions, the mere highlighting of proletarian grievances proved incapable of intensely politicizing the sublaterns. [8] In contrast, right-wing politics played on subaltern longings, creatively mobilizing the latent energy of these subjective frictions. It created a discourse that Ajay Gudavarthy describes as “pro-corporate but anti-modernity”. [9] It helps push for high-end capitalist growth with all its attendant problems of fragmentation and urbanization while at the same time addressing the communal anxieties that capitalist modernity introduces. The legacy of a pure past - through the invocation of civilizational, cultural or religious ethos - can be enjoined with claims for a radically altered future. These interpenetrating ideological amalgams foreground the need for Left politics to be more imaginative in its fight for socialism. Without the incorporation of an experiential dimension in its mode of praxis, the Left will also be incapable of uniting the various identity-recognition struggles around the “concrete universal” of class. [10] Concrete universality, unlike the abstract universality of class reductionism, recognizes the lay normativity of identitarian experience yet goes beyond it. The need for such a political praxis can’t be emphasized enough. Notes

Works Cited Appadurai, Arjun. “A Syndrome of Aspirational Hatred Is Pervading India,” The Wire, 10 December, 2020. https://thewire.in/politics/unnao-citizenship-bill-violence-india. Gudavarthy, Ajay. “Theorizing Populism: Lessons Learned from the Indian Example,” in The Politics of Authenticity and Populist Discourses: Media and Education in Brazil, India and Ukraine, eds. Christoph Kohl, Barbara Christophe, Heike Liebau and Achim Saupe (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 53-69. Sayer, Andrew. The Moral Significance of Class (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). ---. “Class, Moral Worth and Recognition,” Sociology, Vol. 39, Issue 5, 1 December, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0038038505058376. Wood, Ellen Meiksins. Democracy against Capitalism: Renewing Historical Materialism (New York: Verso, 2002). Iqbal, Yanis. “The Revolutionary Potential of Hope and Utopia,” Hampton Institute, 10 December, 2020. https://www.hamptonthink.org/read/the-revolutionary-potential-of-hope-and-utopia. ---. “The Rise of the Right in the Neoliberal Era,” Midwestern Marx, 10 May, 2021. https://www.midwesternmarx.com/articles/the-rise-of-the-right-in-the-neoliberal-era-by-yanis-iqbal AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Archives June 2021

0 Comments

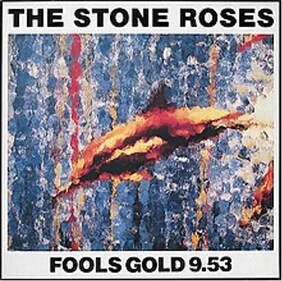

The Marquee de Sade don’t wear no boots like these Capital’s cultural hegemony is within all of us, by definition. We acquiesce to capital’s hegemony because we’ve bought into capital’s value system voluntarily, enforcing it with our own consent. All of us being temporarily embarrassed millionaires, as the saying goes, we hang onto the dream like grim death, capital fighting the collapse of its hegemony over our minds every step of the way. It is a long journey, marked by cognitive dissonance, denial, hope against hope. It has to be beaten out of us, by ourselves and our own experiences, each individual traveling the road at a pace impossible to accelerate from the outside. We must convince ourselves it was a mistake to believe, that we were fools from the outset, and therefore must refuse any continued consent. That is the toughest of nuts to crack, because no one likes being made a fool, least of all by their own hand. It did not feel like a fool’s errand to work for two years in five former soviet republics from 1997-1999 for the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI). No, it was a dream come true, within the dream of hegemony. NDI were the good guys; we trained “the opposition parties”. We laid the seeds for the “color revolutions”. I was even, dare I say it, a hero. America had just won the Cold War, the Soviet Union was long gone, so everywhere I went I was treated like Patton’s army liberating France. To a GenXer like me, history really had ended, and I was one of the winners. In 1997, delivering “market democracy” shock doctrine seminar in Armenia through NDI interpreter Gegham Sarkissian (the best in the business) From today’s two decades of hindsight spent at the sharp end of capital’s knife, it’s obvious I was nothing but a tool of capitalist empire back in my glory days, a tiny line item in the neoliberal shock doctrine budget, some dude sent to former soviet republics to “train” political parties and election observers in what we called “market democracy”, whatever the hell that was. It never occurred to me that a wet behind the ears 29 year old Yankee from Cleveland, Ohio “training” a seminar room filled with apparatchiks twice my age in Armenia (or Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan) was something of a Three Stooges episode, like an Onion article traveled through time springing to reality. If a 1950’s B-movie sci-fi flick were made of it now, the title might be “Attack of The Clintonian Blairite Zombie!” The first crack in the hegemony came when I witnessed and documented the comically buffoonish fraud of the spring 1998 presidential “election” in Armenia, held in two rounds to rubber stamp a military coup that January. Many of my long time readers know the story, which I first published online in a long gone blog from 2005. Thinking myself the hero I imagined, I tried to sound the alarm, and was squelched; by the French embassy, my own embassy, even my own employer NDI. The boat we were not to rock was...the status quo. All understood that meant oil, something to do with convoluted pipeline diplomacy across the Caucasus. I will never forget the car ride with my boss, the late Nelson Ledsky visiting from DC afterward, bouncing from one high level meeting to the next, screaming at him from the back seat at the top of my lungs, “Why are we even here??” Nelson’s silence in that car that day stunned me. Something should have clicked, but didn’t. I was so distraught I left Armenia after one year, to spend the next year roaming soviet republics like a vagabond vaudevillian song and dance man, in seminar rooms performing the shock doctrine in a kind of weird hallucination. In Kyrgyzstan, 1998, neoliberal song and dance man, with translator To beat my acquiescence to capital’s hegemony out of me took two decades of beating it out of myself, with countless Saul Off His Horse moments along the way. Cancelled to exile before cancel culture was a thing, two runs for public office to overcome it, a decade of online journalism, Occupy Wall Street, two Bernie Sanders runs for president, a masters degree, all amidst daily life teetering on the edge of capital’s precipice of precarity. Patience is the biggest lesson, not just for my own road traveled, but all who travel it. One advantage us GenXers have is great music to haunt us, maybe even help us, like The Stone Roses, who long ago seemed to know it was all fool’s gold. When the Berlin Wall fell in November, 1989, prior to my launch into transatlantic neoliberal political careerism, I was a new college grad on a gap year before law school, living and working in London on a student work permit at what would eventually end up being Donald Trump’s favorite law firm, Cleveland’s Jones Day. Young GenXers on a neoliberal quest couldn’t pick a better start than to be a copy boy in the London office of one of the world’s largest law firms, which happened to be HQ’d in my hometown. So, I watched the Berlin Wall come down on the BBC. That same month The Stone Roses released their defining single, Fool’s Gold. The Stone Roses’ debut eponymous 1989 album only grows more important to rock history each passing decade, understood today as the seed of countless indie bands, genres, and sounds. Formed in Manchester in 1985, the Stone Roses perfected druggy raves in tiny backroom, upstairs, and abandoned warehouse parties in the middle England underground. Pioneering a heady infectious combo of 60’s melodic psychedelia with funky post punk 80’s guitar jams, Stone Roses gigs had become legendary by the summer of 1989 as the Warsaw Pact cracked to pieces. At the time, the “Madchester baggy” scene merely meant ecstasy fueled all night dance parties. Now, we know on that one album lie roots connecting James Brown to the Velvet Underground to Oasis to punk, to just about everything in rock before or after. It’s all there, especially in Fool’s Gold, which wasn’t even on the album’s initial release. Single sleeve for the long version of Fool’s Gold Promoting their debut album at a record store in Manchester that August, 1989, whispery-voiced lead singer Ian Brown and funky guitarist John Squire heard a compilation of break beat loops which included what is now understood as one of the most sampled drum beats in music history – James Brown’s Funky Drummer. Hooked, Brown and Squire wrote Fools Gold that August over the Funky Drummer loop. First, they borrowed an ear worm bass line from Isaac Hayes’ Oscar winning soundtrack to the 1971 film Shaft. Upon this already worshipful collage, Brown wrote lyrics that today make Fools Gold mythically prophetic. Brown took inspiration from the 1948 Humphrey Bogart film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, a cautionary tale of prospectors turning on each other in a hunt for gold, Bogart eating himself alive with greed. Bogart told a reviewer in 1948, “Wait till you see me in my next picture…I play the worst shit you ever saw!” Director John Huston slowly oozes the evil out of Bogart from the opening scene until he lies dead in a ditch at the end, over gold. Huston’s father, Walter Huston, who won an Oscar for his performance, plays the old timer who sees Bogart coming from a mile away, having lived a life prospecting, knowing that look in his eye, the look greed puts in all our eyes. From the night The Stone Roses debuted Fool’s Gold on the BBC’s Top of The Pops, Thursday, November 23, 1989, two weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was instantly and remains the definitive Stone Roses track. Newscasts that Thursday were still filled with people hacking away at the Berlin Wall for souvenirs. Capturing the euphoria of the moment, Top of The Pops featured the happiest sounding bands on the charts that week - the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays, who both had burst the “Madchester baggy” scene onto a world ready for joy. Happy Mondays performed a song called Hallelujah that night, as if we all had won...something...and history was over. The Stone Roses performed Fools Gold. Today, Ian Brown singing in Fools Gold sounds like a warning from the old timer who saw that look in our eyes, time traveling past the 1989 souvenir chunks of the Berlin Wall to get on with the grim reaping of 21st century covid capitalism. I’m standing alone Naturally, Fools Gold’s lyrics were immediately lost in the blazing haze of Madchester masterpiece. Just dance, we all thought. History was over after all. Words seemed not to matter. In the US, the cliche has always been the Stone Roses never got here; only those deepest into college radio alternative shoe gaze ever found them. MTV gave Stone Roses all they could, featuring Fools Gold on the 12-2am late night alternative show 120 Minutes for months, but the Stone Roses never matched their moon shot debut. History’s brief ending seemed to eat Stone Roses alive, just as greed eats Bogart alive in the lyrics’ inspiration. For GenXers converting to leftism from a lifetime in capital’s cultural hegemony, we must remember - The Marquis de Sade don’t wear no boots like these. AuthorTim Russo is author of Ghosts of Plum Run, an ongoing historical fiction series about the charge of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg. Tim's career as an attorney and international relations professional took him to two years living in the former soviet republics, work in Eastern Europe, the West Bank & Gaza, and with the British Labour Party. Tim has had a role in nearly every election cycle in Ohio since 1988, including Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Tim ran for local office in Cleveland twice, earned his 1993 JD from Case Western Reserve University, and a 2017 masters in international relations from Cleveland State University where he earned his undergraduate degree in political science in 1989. Currently interested in the intersection between Gramscian cultural hegemony and Gandhian nonviolence, Tim is a lifelong Clevelander. Archives June 2021 The Lebanese pound has depreciated about 90% in the past 18 months, driving annual food inflation to 400%, erasing salaries and savings and pushing more than half the nation into poverty. All this comes at a time when the country is battling the devastation wrought by COVID-19 as well as the ravages from the 2020 Beirut blast. Financialization The economic crisis in Lebanon is closely linked to the paradigm of financialization adopted by the ruling elite. This paradigm has converted the country into a “bankers’ republic”. The country that was once known as “the Switzerland of the Middle East” based its economy on the financial sector without regard for the productive sectors. The beginnings of the current morass can be traced to the 1997 “peg,” which artificially fixed the Lebanese pound to the dollar at an overvalued rate, thus laying the ground for the rise of rentier capitalism. On one hand, it became more profitable to import than to produce locally. On the other hand, investing capital in unproductive economic sectors - namely financial products and real estate - became increasingly attractive as the risk of inflation receded. A definite set of problems emerges when a currency is pegged at a high rate. Since the government sets the rate too high, domestic consumers will buy many imports, creating chronic trade deficits. When imports exceed exports, a country’s currency demand in terms of international trade is lower. Lower demand for currency makes it less valuable in the international markets. In response to these devaluationary pressures, the government will have to appreciate its own currency. For this, the central bank needs to buy its currency in foreign exchange markets, paying with foreign currency. Since no central bank has an infinite amount of foreign currency reserves, it cannot buy its currency indefinitely. The government's reserves will eventually be exhausted, and the peg will collapse. To maintain the peg, Lebanon’s central bank had to ensure a continual inflow of foreign currency, namely US dollars. This was done through a national Ponzi scheme - a scam in which existing investors are paid off with funds collected from new investors, while the organizers cream off a share for themselves. With the help of oil money from Gulf Arabs and remittances from the large Lebanese diaspora (estimated at more than 12 million persons, living on all continents), the bourgeoisie built the bases of domestic finance. To further attract money from abroad, Lebanese banks promised high interest rates on deposits. Meanwhile, people who put money into the banks received more than 5% in interest on deposits. It was a great deal for investors in the region, who piled money into Lebanese banks. The money could have been used for productive investments but stayed in the financial chamber. The dollar flows from abroad were used by Lebanon’s commercial banks to speculate on sovereign-debt instruments denominated in Lebanese pounds at interest rates significantly higher than the international market rates granted by the Lebanese central bank. In other words, the banks, flushed with deposits, started lending the money to the government, via the central bank. The banks had promised to pay a high interest rate on the deposits, but the central bank promised to pay even higher interest rate to the banks. It ensured the system could keep going for a little while. The banks turned around and lent the government a lot of money, pocketing the difference between the two interest rates. The high interest rates on government bonds and bank deposits strongly limited investments of capital in the productive economy. Most of the money the state collected through the bonds was in the end used to repay the interest rather than to fund social welfare programs or public infrastructure. While proving to be catastrophic for the working class, this profit scheme enriched bankers. The share of public debt held by banks reached nearly two-thirds in the 1990s, and it is estimated today to be nearly 43%. Indeed, interest rates went up to as high as 40% on untaxed treasury bills, helping the banking sector’s assets grow by 25% between 1993 and 2000 and increase nearly eightfold between 1993 and 2013. In addition, between 1993 and 2018, banks’ net profits increased from $63 million to a whopping $2 billion, representing a 3,000% increase. It is important to note that the process of financialization was fundamentally aided by the political plutocracy. In fact, politicians in Lebanon are closely stitched with the financial magnates. Individuals closely linked to political elites control 43% of assets in Lebanon’s commercial banking sector. 18 out of 20 banks have major shareholders linked to political elite. Moreover, 4 out of the top 10 banks in the country have more than 70% of their shares attributed to crony capital. Only 8 families control 29% of the banking sector’s total assets, owning together more than $7.3 billion in equity. For example, one of the controlling shareholders (over 5% of shares) of Bank Audi is a company wholly owned by Fahad Al-Hariri, brother of the Prime Minister, Saad Al-Hariri. Collapse The collapse of the Ponzi pyramid constructed by the financial oligarchy began in October 2019 with the slowdown of flows of hard currencies in the context of the global crisis of capitalism, and instability in Middle East, particularly in Syria. The expatriation of capital organized by the wealthiest 1% of the population, who dominated the financial sector, exacerbated the lack of cash. The banks, having lent three-quarters of deposits to the government, had become functionally bankrupt and increasingly illiquid. Unable to contain the crisis of their own making, they passed the burden on small depositors by setting illegal and discretionary capital controls that prevented them from withdrawing their pensions and wages. In the hindsight, the crisis of Lebanon’s economic architecture was predictable. The state was borrowing from or via the central bank at exorbitant interest rates, the central bank was borrowing from the local banks, who were lending the money of their depositors, who in turn were lured in by high interest rates. High interest rates of up to 15% kept this unsustainable cycle going for years. But running out of cash was inevitable. When this happened, the entire structure of accumulation broke down. AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Archives May 2021 The neo-fascist moment of neoliberalism has proven to be extremely destructive for the working class of the world. Pervasive mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic by right-wing governments throughout the globe has proven to be extremely costly in terms of the number of lives lost to the infection. However, this political urgency of removing neo-fascist leaders from power has not translated into a deeper re-thinking of the strategies and tactics hitherto used by social justice movements. Instead of critically reflecting on the rise of the Right, they have been busy denouncing the impact of their policies. While the latter is absolutely necessary, the absence of sustained thinking on the various reasons behind the re-emergence of neo-fascist-populist ideas will not allow one to move beyond moral outrage and angry reactions. Thus, what we need is honest introspection on how the various deficiencies of progressive politics played a role in propelling the Right to power. Identity Politics The extension of the neoliberal logic of hyper-individualization into the spheres of social and cultural exchange has shaped the trajectory of progressive politics. In general, the marketization of the public sphere has eroded the bases of collective solidarity in two ways. First, it has personalized the causes of suffering into individual trauma, which can be self-managed. Second, it has relentlessly regurgitated the supposed importance of a unique, authentic, individual identity, thus weakening the foundations for the formation of shared experience. These neoliberal transformations have exerted influence on the recent directions of identity politics, accepted by many movements as a legitimate form of counter-hegemonic assertion. Identity politics, like the neoliberal discourse of authenticity, has adopted a position which states that only those who have experienced an injustice can understand and thus act effectively upon it. This overly subjectivist theory of knowledge - labeled as “epistemology of provenance” - mimics the ideology of private property and of competition in bourgeois society. If the direct experience of oppression is the primary or the only condition for one to develop an insight into oppression and how to fight it, then the implication is that the insight into oppression as a form of cultural wealth is the monopoly of a few as if it is their private property. Another consequence of the subjectivist theory of knowledge is that it perpetuates the individualist fallacy that oppressive social relationships can be reformed by particular subjects without the broader agreement of others who, together, constitute the social relations within which the injustices are embedded. This, again, closely corresponds to neoliberal concepts, namely the undue stress on personal efforts rather than collective struggle. The atomistic tendencies engendered by identity politics’ espousal of an epistemology of provenance get exacerbated when it is complemented with the theory of “intersectionality”. While it is true that a multiplicity of identities are simultaneously acting on an individual, intersectionality’s depiction of identities as descriptive categories leads to the absence of an active interpretation of oppression. This gives rise to the framing of identities as freely floating in an undefined atmosphere of interpersonal relations. Ascriptive identities (like race, gender, or sexual orientation) shift from being understood as, to use Stuart Hall’s formulation, modalities through which class is “lived” to attributes of individuals that attach to them. It becomes part of their “portfolio”, categorizing individuals on the basis of what they are rather than what they do. Thus, identity operates as a commodity, whereby the historical specificity of specific identities through and alongside a capitalist mode of production is mystified. Insofar that intersectional theorists observe no meaningful links between different identities, there only exist many perspectives on oppression, all of which are partial perspectives (e.g. a gender perspective, a race perspective, etc.), and they are all competing, but there is no common ground among them. This situation leads to mere diversification within contemporary power structures as the only conceivable goal. The response to this intra-subaltern impasse has been confused. Ajay Gudavarthy and Nissim Mannathukkaren, while emphasizing that “progressive politics has to move towards affinity and an idea of shared spaces rather than focus on mere claims of essentialised identity”, fail to outline the basis on which this solidarity can be crafted. Class: A Concrete Universal According to identity politics, the cause of discrimination is rooted in the very identity of these groups and their difference from the discriminating group. The rectification of discriminatory attitudes involves the reaffirmation of the identity category, which is necessarily self-reproducing rather than transformative. This is Nancy Fraser’s case when she looks at “affirmative” redistributive remedies, arguing that the repeated surface re-allocations they involve have the effect not only of reinforcing the identity category but of generating resentment towards it; and Wendy Brown’s more general philosophical case when she argues that identity politics are a form of “wounded attachment”, which must reproduce and maintain the forms of suffering they oppose in order to continue to exist. Contemporary identity politics is non-transformative in another dimension. The idea of simple “discrimination” presupposes a liberal understanding of civil and human equivalence as the desired norm, leading to the framing of oppression as a failure of the liberal creed. Liberalism, taken in its late 19th century American usage to mean the inclusion of all groups in a given social whole (workers, women, people of color, etc), does not guarantee equality, as a lack of equality is presupposed by a capitalist system for which inequality is constitutive. Hence, by asking to correct not inequality but differential inequality, identity politics does not end up abolishing inequality. Winning equivalence, identity politics universalizes inequality by distributing it more evenly among all without difference. As we have seen, the struggle for recognition has turned into an arms race, in which cultural identities deploy the language of minority rights in their defense. The inflation of recognition as a political category has also led the displacement of material injustices, and the reification of reductionist identities, which could become increasingly insular. These factionalist cracks in subaltern politics can be plastered with the help of socialist politics which comprehends the centrality of class. However, this understanding should not be interpreted as degrading the significance of identities. As Martha Gimenez explains, “To argue…that class is fundamental is not to ‘reduce’ gender or racial oppression to class, but to acknowledge that the underlying basic and ‘nameless’ power at the root of what happens in social interactions grounded in ‘intersectionality’ is class power.” When a class-based politics is practiced, the entire capitalist system becomes the excluded exterior of the subalterns’ discourse. By identifying a discourse in relation to its exteriority, the internal differences of that discourse are negated and it thereby, enters into a “logic of equivalence”. Logic of equivalence constricts the internal differences within a discourse and instead, describes its identity through a relation of exteriorization. But the construction of equivalential chains is not a smooth process. According to Ernesto Laclau, in a discourse trying to redefine itself according to an equivalential chain, “each difference expresses itself as difference; on the other hand, each of them cancels itself as such by entering into a relation of equivalence with all the other differences of the system.” This means that the parts of that discourse are constitutively split and are afflicted by an inherent ambiguity. The Marxist model of class politics utilizes these productive tensions to generate a vibrant praxis of solidarity. It emphasizes the commonality of the subalterns’ enemies and then the particularity of their own interests and differences. In other words, it recognizes difference while stressing the concrete universality of class, based on the subject’s relationship to the means of production. Concrete universality, unlike the abstract universality of modern liberalism, with its human and civil rights that are so often little more than formulaic to those at the bottom of society, is rooted in social life, yet points beyond the sheer facticity of a complex reality. It is this dialectical feature of concrete universality that allows it to mold identity politics in a radical direction. The identitarian experience provides a point of entry to a potentially radical politics, but such potential will only be realized if its subjects move beyond that unfiltered immediacy to challenge the systems of oppression that generate the inequalities shaping not only their lives, but those of others too. AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Archives May 2021 Egypt is one among the five countries in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) most affected by hunger during the COVID-19 pandemic. Widespread hunger in Egypt follows an international pattern. The World Food Program (WFP), the branch of the United Nations (UN) responsible for delivering food assistance, expects to need to serve 138 million people in 2021 - more than ever in its 60-year history. The inability of the majority of countries of the world to effectively counter-act hunger is a result of decades-long neoliberal policies. These policies have either instituted import dependency or unleashed a process of export-oriented agro-industrialization, thus creating a highly unstable and deficient food regime. Egypt is not immune to these economic factors. Present-day hunger in the country is structurally situated in a pro-bourgeoisie paradigm intended to enrich the few at the expense of others. Economic LiberalizationThe historical context for food insecurity in Egypt is provided by former President Anwar Sadat’s policy of economic liberalization, faithfully continued by Hosni Mubarak till 2011 and by Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi until today. In 1960, Egypt had a self-sufficiency ratio (domestic production in relation to consumption) for wheat of around 70%. By 1980, the self-sufficiency ratio had fallen to 23% as imports rose to massive levels. Food aid and grain imports performed two important functions for imperialist powers. First, they tightly integrated Egypt with the world market and hence exposed it to fluctuating global prices. Secondly, they paved the way for growing levels of indebtedness as access to foreign currency became a key determinant of whether a country could meet its food needs. In Egypt, these developments were an important part of Sadat’s decisive turn toward the U.S. through the 1970s. The 1973 war was estimated to have cost around $40 billion, and the general fiscal squeeze caused by rising food and energy imports led Sadat to seek loans from U.S. and European lenders as well as regional zones of surplus capital such as the Gulf Arab states. The latter played a decisive role in bringing Egypt into the orbit of the American empire, with Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, and Qatar forming the Gulf Organization for the Development of Egypt (GODE) in 1976 to provide aid to Egypt. The condition for Gulf financial aid was the elimination of Soviet influence in Egypt (the Soviet-Egyptian Friendship Treaty was canceled in March 1976) and the implementation of a series of economic reforms prescribed by the US Treasury, IMF, and World Bank, which included an end to subsidies and a deregulation of the Egyptian pound (which would raise the cost of imports). As the Egyptian government moved to amend laws to allow repatriation of profits, free flows of capital, and attempted to lift subsidies, funds arrived from GODE. ImpoverishmentWith the arrival of neoliberalism in Cairo, the masses became increasingly poor. When they became poor, they were unable to buy food in adequate quantities. This was the natural outcome of an unending spate of privatization. In the 2000s, Egypt gained the dubious distinction of being the leader of privatization in the Arab world. The country’s privatization program was launched as part of a Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) agreed between the Egyptian government and the World Bank and IMF in 1991. The major focus of this SAP was Law 203 of 1991, which designated 314 public sector enterprises for sale. By 2008, Egypt had recorded the largest number of firms privatized out of any country in the region and the highest total value of privatization ($15.7 billion since 1988). Unlike other states, in which just one or two deals made up the majority of privatization receipts, Egypt’s sell-off was wide-ranging - covering flour mills, steel factories, real estate firms, banks, hotels, and telecommunications companies. To prepare state-owned companies for privatization, the Egyptian government terminated subsidies and ended their direct control by government ministries. In many cases, loans from international institutions were used to assist in the restructuring and upgrading of facilities prior to sale - burdening the state with debt while investors received newly retooled and modernized factories. The end result of privatization was a severe deterioration in labor rights and wages, facilitated by the growth in informal work conditions and the increasing exploitation of women in “micro” or small enterprises where minimum wage, social security, and other legal rights were not in effect. Informal workers make up over 63% of Egypt’s estimated 30 million employed population, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Egyptian officials say the sector generates nearly 40-50% of the country’s economic output. Informalization of the labor market has systematically immiserated the workers. The poverty rate rose from 25.2% in 2010/2011 to 26.3% in 2012/2013 and 27.8% in 2015, then jumped to 32.5% in 2017/2018, which means that 32.5 million Egyptians are poor according to the “national poverty line” (EGP736 per month and person, about $45). The World Bank pegs the poverty rate even higher, at 60% of the entire population. Inequality across regions is sharp; poverty levels in Egypt’s poorest villages are as high as 81.7%. The Severe Poverty Line also rose to 5.3% in 2015 and reached 6.2% in 2017/2018, which means that 6.2 million Egyptians - according to the national severe poverty line of 491 EGP (about US$25) per month and person - are extremely poor. Agro-export IndustrializationDuring the COVID-19 pandemic, Egypt’s agricultural exports increased significantly. The country became the largest exporters of oranges in the world, as well as strawberries and among the largest in onions. Most of the Gulf countries lifted trade restrictions related to their import of Egyptian products. Egypt’s exports increased not due to a boom in production but because these countries were preparing for an impending crisis. This has greatly affected Egyptians’ access to goods since productivity did not increase but exports did. The heavy focus on export crops rather than local staples is not new. Since the 2000s, rice, maize and wheat production has been pretty much stagnant. As a result, Egyptians are dependent on expensive food imports. In 2016/17, Egypt imported 12 million tons of wheat, over a million tons more than the average for the preceding 5 years. This coincided with 42% annual food price inflation, the highest for 30 years. The Egyptian Food bank, a large charity that feeds the poor, increased its “handouts” by 20%, extending their reach to “middleclass” families - an extent of the pervasiveness of food insecurity. In the current conjuncture, Egypt needs to move beyond the neoliberal model of agriculture which only succeeds in increasing hunger. Liberalization, immiseration and agro-export industrialization - all of them serve to buttress the power of imperialism and facilitate the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few. While there was hope after the 2011 uprising that farmers would enjoy new freedoms and opportunities, it was not forthcoming. On the contrary, farmers have been harassed, they have seen their crops being damaged and there has been considerable police intimidation if farmers have had the courage to challenge aggression from agri-business firms. Small farmers have been bogged down in costly legal proceedings where big landowners have reclaimed land that they had lost during Gamal Abdel Nasser’s agrarian reforms in the 1950s. In addition, small farmers have had to bear the burden of increased rents and expensive farming inputs. An alternative model needs to be urgently established to replace Egypt’s current agricultural architecture which will end up in a seemingly endless “hunger pandemic”. About the Author:

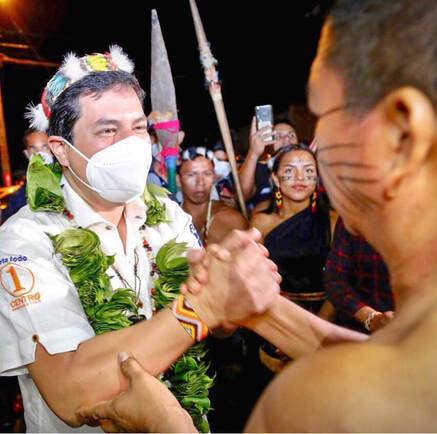

Yanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Ecuador's leftist candidate Andrés Arauz has won the first round of the country's presidential elections held on 7 February, 2021, garnering 31.5% of the vote. An economist and former minister in socialist president Rafael Correa’s government, he has led the ticket for the Union for Hope coalition - what was Alianza País headed by Correa before the party split in 2017. However, it appears that Arauz did not win by enough of a margin to avoid a second runoff, provisionally scheduled for April 11, 2021. The election has been marred by allegations of voter suppression, as Ecuadorians were forced to wait for hours in uncharacteristically long polling lines, especially in areas known to support Arauz. Political ArenaArauz faced two politicians - Guillermo Lasso and Yaku Pérez Guartambel. According to a quick count by the National Electoral Council (CNE), Pérez and Lasso took 20.04% and 19.97% of the votes, respectively. Lasso is the candidate for the conservative alliance “Creating Opportunities” (CREO). He is also a member of Opus Dei, banker and businessman. A true representative of the Ecuadorian oligarchy, he served as a minister of economy in the Jamil Mahuad government in 1999, which fell in the winter of 2000 at the hands of 2 million peasants and poor workers who took over the streets in protest against dollarization. Pérez is the candidate of the indigenous Pachakutik Party. While he portrays himself as an “eco-socialist”, many from the Correa camp have questioned his commitment to defend indigenous communities and remember that some factions of the Pachakutik Party have, in the past, opportunistically aligned with the right against Correa’s government. Moreover, he is also known for supporting US-backed right-wing coups in Latin America and wholeheartedly backing imperialism. CorreismoArauz’s electoral hegemony is explained by the strength of Correismo - the ideology based on the policies of Correa’s government. Between 2007 and 2017, Correa undertook a series of post-neoliberal counter-reforms, strengthening the state, increasing its regulatory and economic planning power, and broadening its social influence. Correa re-constructed Ecuador by way of a Constituent Assembly convened in 2007. In his inauguration speech on January 15 of the same year, he stated: “This historic moment for the country and the entire continent demands a new Constitution for the 21st century, to overcome neoliberal dogma and the plasticine democracies that subject people, lives, and societies to the exigencies of the market. The fundamental instrument for such change is the National Constituent Assembly”. The Constitution set out a social agenda whose essential axes are: (1) social protection aimed at reducing economic, social and territorial inequalities, with special attention to more vulnerable populations (children, youth, elderly); (2) the economic and social inclusion of groups at risk of poverty; (3) access to production assets; (4) universalization of education and health. To this end, inter-sectoral cooperation was initiated among the Ministries of Education, Economic and Social Inclusion (MIES), Agriculture, Health and Migration. The 2008 Constitution established the need to build a health system oriented toward comprehensive health care for the population, called the “Sectoral Health Transformation of Ecuador”, and created the “Model of Comprehensive Health Care”, which provided communal underpinnings to the approach toward healthcare. It is characterized by free health services for users, the deployment of sanitary infrastructure (hospitals and primary care centers) and training for health personnel. Buen VivirThe construction of the Ecuadorian State was based on “good living” (El Buen Vivir) - a conception which places life at the center of all social practices and includes the strengthening of the welfare state in order to guarantee it. Correa acolyte René Ramírez argues that buen vivir means: “free time for contemplation and emancipation, and the broadening or flourishing of real liberties, opportunities, capacities, and potentialities of individuals/collectives to bring that which society, territories, diverse collective identities, and everyone - as a human being or collective, universal or individual - values as key to a desirable life.” An essential part of buen vivir is communal action. While there were many gaps in the achievement of this aim, the Corriesta administration did try to start the “citizenization of political control” - the election of institutional and control authorities not by the legislature, but by an ad hoc organizational structure called the “Council of Citizen Participation and Social Control”. These measures were intended to establish a framework for participatory governance. Neoliberal OnslaughtLenin Moreno assumed presidency in 2017, riding on the back of Correa’s support. Having served as vice president (2007-13) in Correa’s government, he was expected to continue the progressive agenda of a strong welfare state. Instead, Moreno chose to comprehensively break away from the previous paradigm of anti-neoliberalism, persecuting Correa and his supporters. Moreno used a February 2018 referendum to destroy the CNE, the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court, the Judiciary Council, the attorney general, the comptroller general, and others. With the assistance of the CNE, Moreno divided and took control of Correa’s party. When the Correistas tried to re-organize themselves in a new party, the state blocked them. They said that the proposed names were misleading or that the signatures collected were invalid. By 2019, the Correistas used the “Social Commitment Strength” platform to run for local elections in 2019. This platform was then banned in 2020. The suppression of Correistas has occurred against a backdrop of a neoliberal onslaught. Moreno has followed laissez-faire economic policies, privatization, fiscal austerity, deregulation, free trade and state reduction promoted by the Washington Consensus. His initial actions aimed to incentivize private economic activity, including the elimination of advances on income taxes for firms and a move toward labor market flexibility. Further, Moreno introduced tax exonerations for firms that repatriated funds within the next twelve months. In August of 2018, the National Assembly approved the “Organic Law for Productive Development, Attraction of Investment, Employment Generation, and Fiscal Stability and Equilibrium”. This law included amnesty for any outstanding interest, fines, or surcharges owed to a number of government agencies. A 10-year income tax exemption was introduced for new investments in the industrial sector. Along the same lines, a 15-year exemption for investment in basic industries, and a 20-year exemption for investments located near the country’s border, were also specified in the bill. Exemptions were introduced to the tax on capital outflows for productive investments. These measures reduced the high-tax burden that private companies earlier faced. Moreno has announced many austerity adjustments: reduction in the salaries of many government functionaries, elimination of bonus payments for state employees, overall reduction in the number of public sector workers, and the sale of state-owned companies. All this resulted in the “October 2019 uprising”. Hope for SocialismIt is likely that Arauz’s socialist leanings will help him succeed in re-gaining presidential power. He is committed to rolling back Moreno’s neoliberal measures, standing firm against the ruthless demands of international capital, increasing public spending on education and healthcare, and imposing restrictions on capital flight. Arauz has conceived of a state model oriented towards selective economic interventionism for the benefit of the poor. This model argues that the people-centric acceleration of economies is not a spontaneous phenomenon that results exclusively from market forces, but is the result of vigorous state involvement in strategic sectors through planning and structural reforms in the context of a mixed economic system. Considering the fact that absolute poverty has tripled during Moreno’s 4-year presidency, Ecuadorians will elect a leader who promises to provide them with dignified lives. About the Author: Yanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Photo source: Andres Arauz' Instagram - @ecuarauz

In the days after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer in the United States, massive revolts spawned in that country and have travelled fast around the world, getting the center of international attention and gaining massive support. Among those who comment on these events, there has been much (and certainly, there has to be) insistence on the fact Floyd’s murder is not merely an isolated act of racist hatred: it is recognized that racist violence is a systemic or structural issue[1]. Nonetheless, it is very important to clarify what that means. What is that system in which racial violence is framed (inside and outside of the United States)? If this is not explained, pointing out the structurality of racist violence remains at a level of generality in which, without being less true, it ends up being something banal. Of course, I do not pretend to provide an exhaustive analysis or a definitive answer here. I would like to insist, however, that it is crucial for this explanation to understand that, like all phenomena in our society, racism is a historical phenomenon, and a specifically modern one[2]. It is a mistake to believe that it has been present exactly as we know it in all societies; yes, there has always been a difference between one’s own group and foreigners, along with a hierarchy of value between “them” (barbarians) and “us” (civilized), which can include differences based on physical or phenotypic traits. However, racism, the idea that there is a natural fatality, race, that is much more deeply rooted in the being of individuals than any archaic caste, and that innately entails a state of moral, cultural and intellectual inferiority and a servile condition, is a legacy of modern colonialism and the system of slavery that it inaugurates[3]. One must also understand that, contrary to what many liberal advocates of Western civilization maintain, slavery was not some “pre-modern” heritage. Slavery in Europe had been abolished in the 13th century, and in the Islamic world even earlier. Slavery will resurface in the middle of the 16th century, when it is already crystal clear for the whole of society that it is something aberrant, and in a much more degrading way than in any other time in history (a slave in the Middle Ages or in the Ancient World did not inherit his condition by the color of her skin, and she had a much better chance of buying her freedom for herself or her family, and even of moving up socially), because of the interests of the new merchant class that was then beginning to emerge (that is: due to the economic need of cheap labor)[4]. Racism does not precedes slavery: racism emerges after decades of forced servitude, subject to the need for profit of the new capitalist class, to its need to appropriate land and human beings to generate wealth without cost overruns. It is the quasi-natural justification of the situation of oppression inherent to a system of expropriation and exploitation. The history of modern racism and colonialism goes hand in hand with the history of capitalism: they are the same history. That is why it is a mistake to think that capitalism is merely “an economic system”. Capitalism is, above all, a system of domination based on expropriation and exploitation. And that is also why, although it is correct to celebrate the awareness of the masses who, exercising their legitimate right to disobedience, unleash their indignation and furious protest[5], we must not remain complacent in the pure celebration of revolt (which without organization and a clear strategic route, always ends up fading away). Eliminating racist structural violence, overcoming the oppression of peoples of colonial origin and exploited labor throughout the world, requires thinking about a radical reorganization of the economic and political system that we call capitalism (to think, without fear, in its opposite). We must think and speak without fear of socialism, and think and speak without fear about how we must organize to overthrow the social class that to this day benefits from the most savage injustice. Regarding this reflection, I believe that Marxism (with 180 years of theoretical and practical experience in Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas) has much to contribute. Citations [1] In the case of the United States, this becomes evident to those who contemplate the figures and the systematicity with which the Afro-descendant population suffers this kind of violence by the punitive institutions of the state. In the case of Peru (my country), a similar argument could be made in relation to the mestizo and indigenous population. [2] See Allen, T., The Invention of the White Race (2012). Also, I. Wallerstein and A. Quijano, “América como concepto o América en el moderno sistema mundo”, in Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales vol. XLIV n°4, 1992. [3] See Losurdo, D., Class Struggle: A Political and Philosophical History (2015). [4] Indeed, it is interesting to see how European society, in the centuries before the restoration of the slave trade, had already generated institutions and normative resources to question the practice of slavery (the antislavery position of the theorist of absolute monarchy Jean Bodin can be contrasted with that of the “father of liberalism”, John Locke, whose defense of private property included a defense of slave ownership in the colonies). The Catholic Church and the monarchical state, despite all of their despotism, often played a positive role in this regard. It was against the “illegitimate” interference of these “illiberal”, pre-modern powers in regard to the administration of their possessions that liberalism as a doctrine would be born. See D. Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counter-History (2005), and for a more general history of “primitive accumulation”, see the first volume of Marx’s Capital. [5] See Celikates, R., “Rethinking Civil Disobedience as a Practice of Contestation – Beyond the Liberal Paradigm”, in Constellations Volume 23, n°I (2016). About the Author: Sebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Originally published in Disonancia: Portal de Debate y Crítica Social (Jun 4, 2020)

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed