|

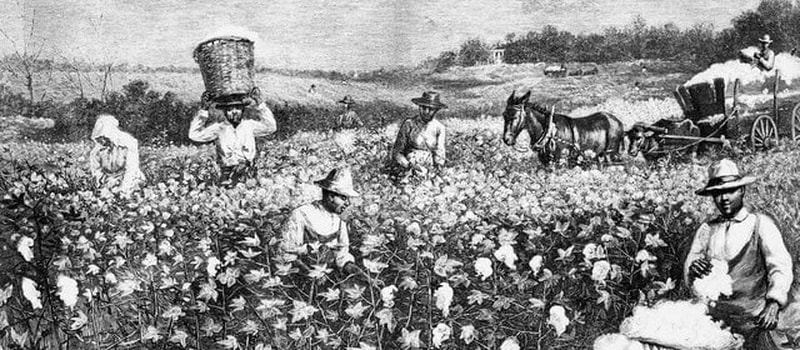

Edward Baptiste’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism attempts to provide a material analysis of the development of Slavery in the United States leading up to the Civil War. In doing so he reveals the origin of capitalism, and Western Economic Supremacy, to be the Southern Slave Plantations, who provided Northern and English Capitalists with an endless supply of cheap cotton, picked by the hands of slaves. As Eric Foner of the New York Times said in his review of the text in 2014 “American historians have produced remarkably few studies of capitalism in the United States” (Foner). Given the lack of analysis that has been done on the development of Capitalism in the United States, The Half Has Never Been Told, serves as an incredibly useful tool for American socialists who seek to understand the historical development of Western Capitalism, so that we may destroy it, and reconstruct a superior system. Let us first quickly review Marx’s concept of Surplus Value, and his critique of Political Economy, in a manner that hopefully avoids putting the reader to sleep. A common attack often levied at modern day economists, is that their field of study seems to have no place for historical analysis. To most Western Economists, capitalism’s laws are viewed as “natural.” The field has given very little thought to the historical development of capitalism, or the systems which predated it. In the 1800s, Karl Marx found this to be a major flaw in the works of Classical Economist David Ricardo. Marx argued in Capital Vol 1 “Ricardo never concerns himself with the origin of surplus-value. He treats it as an entity inherent in the capitalist mode of production, and in his eyes the latter is the natural form of social production” (Marx 651). Marx makes this critique of Ricardo, after he himself first laid out a lengthy history of the development of capitalism in Europe, which took place over hundreds of years. Marx’s analysis of production shows us that surplus value, or excess value beyond what society needs for survival, is not present in all modes of human production historically, nor is it exclusive to the capitalist mode of production. Marx draws our attention to the Egyptians, who’s advanced agricultural infrastructure allowed their society to produce what was needed to survive, while using their leftover time to construct giant pyramids in honor of the Egyptian monarchs. The pyramids themselves would be considered “surplus value”, however, they do NOT constitute the specifically capitalist form of surplus value. This is because the Pyramids were produced to show the power of monarchical rulers, and not to make money for a capitalist through their sale on a market. The domination of Private Property owners and giant global commodity markets would take years of development before coming about. Only after years of struggle between classes would capitalists finally wrench the means of production from the hands of monarchical rulers. These specific historical developments led to a change in how Surplus Value is produced. Now, rather than producing what is needed to maintain society, before using any extra time to construct surplus commodities for the monarchy, Surplus Value is produced through capitalists hiring workers, who then add value to a commodity, before selling that commodity on a market, at a price above it’s actual value. Under this capitalist mode of production, the creations of the working class, beyond what is needed for the survival of society, becomes the property of the capitalist class. This excess property appropriated by Capital is Surplus Value within a capitalist mode of production. In his studies, Marx also found that the capitalist mode of production develops uniquely to every country and geographic location. In Capital, he often jumps around the world to look at the development of capitalism globally, but primarily narrows his analysis to the development of capitalist production in Europe. Here, Marx observed the rapid development of privately owned textile factories. An analysis of the productive output of these factories showed they had been producing commodities at an ever-increasing rate. This output of commodities was maintained and constantly increased by throwing young girls into the factories en masse. If girls died of overwork or succumbed to diseases contracted in the horrid factory conditions, capitalists looked to the newly created mass of unemployed workers to hire a replacement. Additionally, the machinery of production was constantly being improved. Factory owners were now competing with one another to sell the maximum number of products possible. The winners of this newly emergent capitalist competition were those who could produce the most while paying their workers the least. Capitalism becomes a race to produce surplus value, with no regard for the effects it has on the class of workers. During the time of capitalism's original development, the textile capitalist’s most important raw material was cotton. Thankfully for these European capitalists, they would find an abundant source of cotton at ever affordable prices directly across the Atlantic Ocean. Edward Baptiste’s The half has Never Been Told may as well be a contribution to Marxist theory for those of us living here in the US, the world’s capitalist stronghold. Upon its release, Baptiste’s book was lambasted by those who Marx would have referred to as ‘bourgeois economists.’ One article from The Economist was removed after the Publication received backlash over their critique that “Almost all the blacks in his book are victims, almost all the white’s villains” (The Economist). Perhaps economists in the United States have not yet been made aware that the capitalist mode of production they claim to study so closely developed slowly out of a system of chattel slavery, which specifically targeted those with black skin. However, someone should make these folks aware that throughout the 19th-century, capitalists in the Northern United States, Europe, and anywhere else the capitalist mode of production had taken hold, were profiting greatly from cotton picked by black slaves in the southern United States. Despite what our modern-day economists would have you believe, black people were in fact victimized by white owners of capital. These white landowners did all they could to commodify the black body in order to create for themselves an endless source of labour power. This labour could theoretically provide capital with an endless source of surplus value, so long as that labor could be combined with land, which of course was quickly being acquired through the genocide and forced removal of native populations. Painstakingly conducted research from Baptiste and others reveals Southern Slavery to be its own specific mode of production. So, while Southern Slavery had unique elements which made it distinguishable from Capitalism, they also shared many of the same features. Therefore, the class of Southern slave owners did not have the same motivations as the previously mentioned ruling class of Egypt, who also produced goods under relations of slavery. Instead, plantation owners in the south were subjected to the same market forces as their capitalist counterparts in Europe. Slave owners produced incredible amounts of surplus value through selling their cotton on a world market which provided endless demand for their commodity. Unlike Egyptian enslavers, the surplus value of southern plantation owners did not come in the form of giant stone creations, or sculptures to the gods. The surplus value appropriated by enslavers instead came in the form of money. Much of which was then reinvested in expanding production through purchasing more slaves, plantations, and land. This money used to make more money is what Marx labeled as ‘Capital.’ The endeavors of these Southern enslaver capitalists were heavily financed by banks in Europe and the Northern United States. These financial institutions simultaneously bank rolled massive campaigns of forced removal or genocide of Native peoples, aimed at divorcing them from the land and allowing market-based production to expand. The Native people’s own unique Mode of production had to be destroyed in order to make room for the production of capitalist’s surplus value. The enslavers of the United States essentially functioned as capitalists, subject to the same market forces as the factory owners who Marx studied in Europe. However, plantation owners held a unique economic power that would come to be enforced by the state. This power was the legal ‘right’ not just to commodify human labour power, but the source of that labour power. Human Beings. Through the legal commodification of human beings with black skin, Southern Enslavers used the labor of black bodies to produce obscene quantities of cotton. The sale of these commodities on the Global Market allowed plantation owners to accumulate massive hoards of wealth, and continue their expansion by endlessly investing capital. The brutality of these enslavers was either ignored or justified by capitalists around the globe who saw the South as an endless source of cheap cotton. Black slaves existed under relations of slavery, while also being subjected to market forces that are usually associated with capitalism. These specific economic conditions incentivized white plantation owners to subject those who toiled in their fields to some of the most horrific crimes in human history. Similar to European capitalists who were consistently working children to death in order to maximize output, Southern slave owners sought any methods possible to increase the quantity of cotton they could produce. Because slave owners had legally enforced ownership of the physical bodies in their labor force, torture became the primary method used to force slaves into increasing the speed of cotton production. Baptiste draws on an analogy from former Politician, and fierce ideological advocate of slavery Henry Clay, who describes a “whipping machine” used to torture enslaved people and make them work faster. Baptiste explains it is unlikely the whipping machine was a real device that existed in the Southern United States. He instead argues that the machine is a metaphor for the use of torture which was the primary technology used by enslavers to increase their production of cotton. While technological innovations such as the cotton gin allowed for an increase in the amount of cotton which could be separated and worked into commodities, far less technology was developed to aid in the process of actually picking the cotton. Therefore, in order for slave owning capitalists to increase the speed of cotton picking on their plantations, the use of torture was systematized and ramped up to an unimaginable degree. Torture was to the slave owner, what developments in machine production were to the factory owner: a tactic for continually increasing the Rate of Exploitation, or the quantity of commodities produced by a given number of workers, in order to produce an increased number of goods for sale on a market, which brings the capitalist his surplus value. There are many ways in which capitalists can increase their rate of exploitation. The specific function of the whipping machine was to increase what Marx called the ‘intensity of labour,’ i.e., an increase in the expenditure of labour and quantity of commodities created by the workers within a given time period. For example, a slave owner hitting a field worker with a whip until the worker picks double the cotton. This would be an increase in the intensity of labour. There are many ways for capitalists to increase the rate of exploitation without increasing intensity of labour. Two common techniques used by non-slave owning capitalists at the time were increasing the productivity of their machinery and increasing the length of the working day. As was discussed previously, very few technological innovations were created in the realm of cotton harvesting during the time of Southern Slavery. Additionally, the Slave Owners already had free reign to work their labour as long as they pleased, and an extension of the working day would serve them no purpose. Slave owning capitalists had a choice to either give up their pursuit of surplus value or use torture on a mass scale to increase the speed at which their workers produced. Of course, the capitalists chose torture, and the market rewarded those capitalists who refined their torture techniques the furthest. Market competition compelled most all Southern capitalists to adopt torture as an incentive of production or be pushed out of business by those who did. The innovation of the market at work! Slavery would only die in the United States after a long and protracted struggle between opposing classes culminating in the Civil War. Baptiste details this struggle in his book and in the process refutes the utopian historical myth that the labor of slaves was simply less efficient than wage-laborers, which is what led to the implementation of capitalism. Baptiste instead shows how Northern Capitalists came into a political conflict with the Southern Enslavers. Northerners began challenging the southern capitalist’s unique ‘right’ to own human beings. By the Civil War plantation owners had long been expanding into Mexico while continuing to steal land from Native Americans. Now running low on conquerable land, the enslavers sought to expand their control to various US colonies, or even extend slavery into the Northern US. This brought Southern Slave Capital into a direct conflict with Northern Capital. By 1860 The North had developed a diversified industrial economy, albeit with the help of cotton picked by slaves. The South on the other hand had seen moderate industrial development, but mostly served as a giant cotton colony for the rest of the world’s capitalists. This limited diversification in the cotton dependent Southern economy and left them slightly less prepared for war. This, among other factors, allowed the Union to win the Civil War replacing slave relations with capitalist ones. Additionally, the Slaves and many workers who hated the Southern Plantation Oligarchy would take up arms and join the Union Army. We see in the civil war the intensification of struggles between classes, which reached its climax in armed conflict between the warring classes. Whether he’s done so intentionally or not, Edward Baptiste’s history of slavery has provided great evidence for Karl Marx’s theory that struggles between classes are what drive history through various modes of production. For those of us living in the United States who wish to wage a struggle against our current mode of production, the history of Southern slavery is necessary to understand. Marx conducted his historical analysis of the development of Capitalism in England with the explicit goal of helping workers to understand their current situation and how to change it. Similarly to Marx, American socialists have the imperative to understand the historical development of our own capitalist mode of production. A history that shows without question that the propertied class in this country has consistently used race as a tool for maximizing their own surplus value. The commodification of a specific race being the ultimate form of this. Today, capital seeks to sow racial divisions among the diverse mass of working people. This is done to distract the labourers of society from the forces of markets, our relations of production, and designed to maximize our exploitation for the enrichment of a small number of people who do not work, the capitalists. The union army destroyed the uniquely evil mutation of capitalist production that was southern slavery. Let us continue this struggle today by attacking capitalist production at its roots, and take power from the class who exploits us, and the markets which throw our lives into anarchy. Bibliography The Economist. “Our withdrawn review "Blood Cotton."” The Economist, 5 September 2014, https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2014/09/05/our-withdrawn-review-blood-cotton. Accessed 29 06 2021. Foner, Eric. A Brutal Process. New York Times, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/05/books/review/the-half-has-never-been-told-by-edward-e-baptist.html. Accessed 02 07 2021. Marx, Karl. Capital Volume I. Penguin Classics, 1976. 3 vols. AuthorEdward Liger Smith is an American Political Scientist and specialist in anti-imperialist and socialist projects, especially Venezuela and China. He also has research interests in the role southern slavery played in the development of American and European capitalism. He is a co-founder and editor of Midwestern Marx and the Journal of American Socialist Studies. He is currently a graduate student, assistant, and wrestling coach at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. Archives July 2021

1 Comment

5/8/2021 The Minutiae and Microscopic Anatomies of Capital: Examining Marx’s Commodity Form. By: Calla WinchellRead NowIn Marx’s ambitious work Capital: Critique of Political Economy he has a daunting goal: to describe the functioning of capitalism that corrects the blindness of the preceding political economists that he had encountered. He seeks to denaturalize capitalism and to demonstrate the exploitative nature of its very foundations. This chapter epitomizes the method used throughout the text, which Marx builds on the back of the concept of the commodity form. Using the most quotidian concepts, like commodity and then the money equivalent, Marx makes the seemingly familiar feel mysterious through his “microscopic” gaze (Marx 90)[1]. Furthermore, through this scientific methodology, Marx reveals the strange homogenizing urge of capitalism, where everything is made equivalent through the money form. For example, where labor, previous to capitalism, was understood by its particular characteristics —what type of labor? What product? — under capitalism it becomes understood as an average “congealed” form of labor, with no particularities. Tracking capitalism’s impulse to make uniform provides a trail that Marx tracks, from the commodity form all the way to the “fetishism of commodity”. Capitalism, like the systems that came before it, lays claim to its own naturalness as proof of its necessity and inevitability. Seeking to problematize that viewpoint, Marx seeks to make the seemingly natural and unexamined aspects of capitalism alien. This reexamination, from a distance, of the foundational concepts of capitalism begins with the very smallest constitutive element: the commodity form. Marx acknowledges that, “the analysis of these forms seems to turn upon minutiae. It does in fact deal with minutiae, but they are of the same order as those dealt with in microscopic anatomy” (Marx 90). Though it “seems” to be minute, the commodity form is the heart of Marx’s labor theory of value, which posits that value is generated, not in the sphere of exchange, but in the sphere of production, when labor is performed. Marx adopts a scientific mode of inquiry, rather than an outrightly polemical or didactic mode. This choice manifests in many ways, from the metaphors he uses to more methodological questions of organization. He sketches out his view of capitalism as a living organism in his preface to the first German edition of Capital, saying that political economists had studied capitalism as one might an animal. “The value-form, whose fully developed shape is the money-form, is very elementary and simple. Nevertheless, the human mind has for more than 2,000 years sought in vain to get to the bottom of it all, whilst on the other hand, to the successful analysis of much more composite and complex forms, there has been at least an approximation” (Marx 89-90). In contrast, Marx seeks to describe the cellular level of capitalism. More importantly still, he seeks to prove that it is not the commodity that is “the economic cell-form” but rather value derived from labor. Turning his microscope to the commodity form, Marx argues that the commodity form is only an advent of capitalism. In order to be a commodity, an article must have “use-value” and “exchange-value”. The former essentially means that the object in question has utility that is separate and beyond its ability to be exchanged. While use-value is transhistorical, because objects have had utility since humans began using tools, the latter is contingent upon the advent of capitalism. Exchange-value means that one object can be exchanged for a certain quantity of another; the two object-types being exchanged need not be equivalent in quality and indeed, they rarely are. When viewed only as a bearer of exchange-value, the particular utility of an object is not considered. The exchange of two qualitatively different items is made possible because they share one common property: “that of being products of labor” (MER 305). This shared fact of being products of labor presumes that this labor is qualitatively the same, even though the true production process might require very different methods —spinning yarn versus carving wood, for example— and thus appear to be quite different. However, in the logic of capital, there is an abstract form of labor, what Marx terms a “congelation of homogeneous human labor” (MER 305). Essentially, this means that labor is quantified with the “socially necessary” time needed to produce something “under normal conditions” and “with the average degree of skill” (MER 305). Thus, value is a result of the labor-power expended on average, by an unskilled laborer, to produce the commodity in question. Simply put, commodity is best understood as value embodied. For example, the ingredients of a cake —sugar, flour, milk— lack as much value as the fully baked cake itself. Since the necessary components are purchased either way, the difference must be understood to be in the labor performed by the baker upon the materials which produced the higher value cake, as opposed to the unacted upon (un-labored) ingredients alone. In order for an object to have value —and so become a commodity— it must possess a use-value and an exchange-value. If it lacks the first, then the object will not be purchased, no matter the hours of labor spent producing it. Lacking the second would mean that no labor had gone into producing it, though it can still have a use-value. Marx’s specific term for such an object is “the spontaneous products of nature” like sunshine or wind, which qualify as something with use-value but that cannot be exchanged precisely because no labor-power has been expended on it. Where use-value relies on the qualitative, meaning it depends on the specificity of the object’s particular utility, exchange-value is the reverse. This means that value is “totally independent of [its] use-value” (MER 305). This dichotomy between the particularity of transhistorical use-value and the homogeneity of exchange-value plays out again and again in Marx’s account, exposing capital’s desire for exchange of uniform equivalents more generally. After detailing the components of the general commodity form, Marx proceeds to talk about the specific commodity form of labor-power. Marx distinguishes between the production of goods in previous eras from the production of goods under capitalism, pointing to the division of labor as a key difference. Citing textiles—a common example for Marx— as an instance of change in history, Marx writes “wherever the want of clothing forced them to it, the human race made clothes for thousands of years, without a single man becoming a tailor” (MER 309). Without a sphere of exchange such division would be highly impractical. Yet, for all the dividing of labor into specializations that capitalism necessitates, there is presumed to be an abstracted idea of the average worker’s ability to perform relatively unskilled labor. This more general concept of labor might seem to undermine Marx’s claim about the division of labor’s importance, but it instead serves to highlight the lack of true “specialization”; any human can perform the kind of tasks that Marx’s labor theory of value rests upon. This sense of labor as homogenous is not, however, able to be translated across societies. Marx makes it quite clear that abstract labor can only be abstracted for current societal contexts; it cannot be translated across borders or eras. In other words, the abstract labor of a farmer in the 17th century will not be the same abstracted labor for contemporary workers, and so it should not be applied universally. The “special form” of the commodity of labor-power is distinct because in its consumption, more value is generated (MER 310). The essential nature of the general commodity is one of consumption. Purchasing something gives access to the use-value of the object, which is used and then used up. In this normal paradigm, the object is depleted of value through use. In contrast to this general commodity form, the commodity of labor-power generates more value as it is used, for the laborer generates new value through their labor. So, the use-value of labor-power is its potential to generate still yet more value. This quality is what supports the labor theory of value. While abstract labor is simply what the average person can be expected to produce over a duration of time, how might one account for more skilled labor under this theory of value? Marx writes that this should be understood as “simple labor intensified” or “multiplied simple labor”. So, one hour of skilled labor might be equal to three unskilled labor hours. Given that these are made equivalent, Marx argues that all labor in his system should be understood as unskilled, “to save ourselves the trouble of making the reduction” (MER 311). Once again, the desire for standardization and uniformity of capitalism stands in contrast with the particularities of different labor. Marx has set out in the section to give an account first of the commodity form, as an essential building block of capital. After he describes this basic structure, he moves to the more particular question of a universal equivalent commodity. The necessity of this universal equivalent commodity, namely a money form, is essential for the functioning of capitalism. In order to describe a universal equivalent, Marx describes first how two commodities can be made to relate to each, so that one commodity expresses itself as the equivalent of another, different commodity. Marx writes, “the relative form and the equivalent form are two intimately connected, mutually dependent and inseparable elements of the expression of value; but, at the same time, are mutually exclusive, antagonistic extremes” (MER 314). In order to form a relationship between two commodities it is necessary to make one relational to the other, translating its value into another form. This second commodity simply expresses the first, but cannot express beyond that. In other words, there can only be one “unit” or one commodity which expresses itself and the other, relational commodity as well. The first commodity, which Marx terms “the relative form”, is embodied in the second chosen commodity. To return to the baking metaphor, we’ll assume that three bags of flour is the equivalent value of one cake. Cake is here the equivalent, and flour is the relative. This relational form points to the “special form” of labor as a creator of value. It is the cake and the flour’s state as products of labor that allow for their equivalence. It is a creation of equivalence that, “brings into relief the specific character of value-creating labour, and this it does by actually reducing the different varieties of labour embodied in the different kinds of commodities to their common quality of human labour in the abstract” (MER 316). One only needs to take this relational comparison a bit farther to arrive at a universal equivalent. In the previous example, cake is fitted to the role of universal equivalent, but a true money-form allows for easier still expression of relations of value-created-by-labor. The money form becomes the only equivalent, achieving “a directly social form” because it allows for relations of meaning to form between commodities and this new equivalent (Marx 161). However, the larger sociality of relation between laborers is further obscured. The homogenizing impulse that Marx has revealed with his comparisons between use-value and exchange-value, concrete labor and abstract labor, gains full expression with the mysteriously mute fetishism of commodity. All relationship between laborers is disappeared behind the gleam of the universal equivalent; meaning is displaced from its proper understanding of the sociality of labor, onto the abstracted universal equivalent commodity, the money form, which he discusses in the next chapter. It is a commodity, because it is value embodied —and thus, labor embodied— and because it has use-value, in that it allows for easy exchange between products, thus able to “satisfy the manifold wants of the individual producer” (MER 322). This ease of exchange directly obscures the “peculiar social character of the labor that produces” this fetishism of commodity (MER 321). Though, as Marx observes, “a commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood”, through tracing the origin of the value derived from commodity to the expenditure of labor-power, Marx reveals the essentially unnatural and mysterious nature of the building block of capitalism: the commodity form. Examined under his “microscopic” view, the familiar is made alien to us, and capital can begin to be “de-naturalized”. [1] I used two editions of this chapter, as the Marx-Engels Reader seems to have abridged some sections. I will cite the Reader using the acronym “MER”. All other citations refer to the translated version of the whole text. See Work Cited for details. Citations Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Marx-Engels Reader. Ed. Robert C. Tucker. 2nd ed. New York: Norton, 1978. Print. Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Trans. Ben Fowkes. London, UK: Penguin, 1992. Print. AuthorCalla Winchell is trained as a writer, researcher and a reader having earned a BA in English from Johns Hopkins University and her Masters of Humanities from the University of Chicago. She currently lives in Denver on Arapahoe land. She is a committed Marxist with a deep interest in disability and racial justice, philosophy, literature and art. With the dislocation of the neoliberal normality by the COVID-19 pandemic, one has witnessed attempts by influential organizations and specific sections of the intellectual elite to resuscitate dormant ideas. A sudden support for Keynesianism is a good example of this. The 2020 “Trade and Development” report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) says that the problem is, “The world largely abandoned the imperative of demand management with the turn to neoliberal policies in the 1980s and an exclusive focus on measures to boost growth from the supply-side.” In the end of the same year, the Financial Times of London - one of the leading bourgeois newspapers of the world - ran an editorial entitled “A better form of capitalism is possible”. It praised John Maynard Keynes, among others, “for realizing that capitalism’s political acceptability requires its adherents to polish off its rougher edges.” Instead of wholeheartedly accepting the post-pandemic plans being relayed by powerful groups, the Left needs to critically evaluate them. In the case of Keynesianism, there has remained fundamental ambiguity regarding the utility of those ideas. With the onset of neoliberalism, many leftists have preferred returning to the Keynesian policy regime, characterized by countercyclical macroeconomic management by an interventionist, regulatory state committed to achieving full employment and higher incomes for everyone. These confusions stem primarily from how one understands the demise of Keynesianism as a hegemonic project of global capitalism. Inaccuracies related to these issues motivate leftists to think that Keynesian policies can always be replicated successfully. Therefore, one needs to explore the death of Keynesianism to show how the project of seeking greater benefits within capitalism is doomed to failure. The Death of Keynesianism Economists agree on the point that profit rates fell from the late 1960s until the early 1980s. According to Edwin N Wolff, the rate of profit fell by 5.4% from 1966 to 1979. However, there is disagreement on the reasons behind this fall. There is the widely held view this drop resulted from a wave of international workers’ struggle which supposedly forced up workers’ share of total income and cut into the share going to capital. This theory defies empirical data and fails to understand the objective laws of capitalism. First, there had been no increase in the share of wages in the Keynesian era when tax, capital depreciation and various other factors are taken into account. Second, no crisis can simply be explained by a wage-squeeze on profits due to the simple fact that capital accumulation inexorably tends towards the revolutionization of the means of production - and thus the augmentation of productivity and the rate of exploitation. The continuous enhancement of productivity is driven by the dynamics of competition. The capitalist does not respond to competitive pressure by passively cutting prices or curtailing production, and accepting a lower rate of profit, but by increasing the exploitation of workers, or by installing new methods of production, in order to cut costs. Meanwhile, the capitalist with a competitive advantage does not sit back and enjoy his share of the market, but expands production in order to capture the market of others. In this process, a reserve army of the unemployed is also created by technological and other means, so as to undermine the position of labor. Third - and related to the second - there exists what Rosa Luxemburg called “the law of the falling tendency of the relative wage”. The relative wage is defined by Luxemburg as “the share that the worker’s wage makes up out of the total product of his labor”. According to Luxemburg, in the capitalist mode of production the absolute wage (both nominal and real) can rise, but the relative wage can only decline, because of “the progress of technology that steadily and relentlessly reduces the share of the worker.” In her opinion, the fall in the relative wage is “a simple mechanical effect of competition and commodity production that seizes from the worker an ever greater portion of his product and leaves him an ever smaller one, a power that has its effects silently and unnoticeably behind the back of the workers.” Therefore, the absolute wage can rise at the same moment that the relative wage falls. Before looking at the actual causes behind the decline in the rate of profit, it is important to note that the workers did experience political potentiation during the concerned period in the form of trade union militancy. Welfare measures and the maintenance of near-full employment conditions improved the bargaining power of the proletariat. The provision of unemployment assistance likewise stiffened the resistance of the workers. As Prabhat Patnaik wrote: “The ‘sack’ which is the weapon dangled by the ‘bosses’ over the heads of the workers loses its effectiveness in an economy which is both close to full employment and has a system of reasonable unemployment allowances and other forms of social security.” The primary reason behind declining profits lay in the rising “organic composition of capital”, defined as the ratio of constant capital and variable capital. It represents the ratio in which the capital outlay - the sum of money that starts the circuit of capital - is divided between purchasing non-labour and labour inputs to production. Thus, it approximately denotes what contemporary economists call the capital intensity of production, i.e., how much non-labour inputs are used by each unit of labour-power. It has an intimate relationship with the rate of profit. If the total capital turned over in one year is composed of a constant component, C, which corresponds to the raw materials and means of production used, and V, which corresponds to the amount of capital laid out to buy labour power, the rate of profit is defined as the ratio of the surplus produced in one year, S, to the total capital turned over, C + V i.e. S/ (C+V). The ratio expressing the rate of profit represents the income of the whole capitalist class as a proportion of its total capital outlay. From the perspective of the capitalist class, there is no difference between the two components of capital outlay, constant capital and variable capital, as far as the return on capital outlay is concerned. The capitalist only focuses on the return on the total investment, the sum of constant and variable capital. This is the structural reason for the inability of capitalists to recognize profit income as the unpaid labour time of workers i.e. to accept the existence of exploitation in capitalist economies. To highlight these aspects in the rate of profit, Karl Marx divided both the numerator and denominator in the expression for the rate of profit with variable capital, to get a useful expression: rate of profit = (S/V)/ (1+C/V) where S/V is the rate of surplus value, and C/V is the organic composition of capital. From this, it is immediately obvious that the rate of profit varies inversely with the organic composition of capital. A study of the US economy showed a rapid growth in the ratio of capital investment to workers employed in manufacturing by over 40% between 1 957-68 and 1968-73. One study of the UK showed a rise in the capital-output ratio of 50% between 1960 and the mid- 1970s. Increasing organic composition did not independently precipitate the crisis of the Keynesian regime; it was the intervention of the overlapping contradictions of a permanent arms economy and growing international competition that completed the downfall of Keynesianism. The huge arms spending during the Cold War had the effect of stabilizing the system economically by counteracting the rate of profit to fall. The reason: enormous investments in armaments that didn’t flow back into the economy, either as commodities for workers’ consumption or as investment into new plant and equipment. As a result, the organic composition of capital rose much more slowly than it otherwise would have. That, in turn, helped sustain profit rates in the US. This effect weakened by the early 1970s as new competitors without the same burden of arms spending - namely, Japan, Germany, and newly industrializing countries - asserted themselves in global markets. The US - burdened by high military spending -became less competitive on the world market against the freshly rebuilt economic powers in West Germany and Japan. Neither Japan nor Germany had been permitted to engage in military spending, leaving their respective capitalist’s to engage in a frantic level of accumulation. This undoubtedly increased the organic compositions of their national capitals but it also reduced the prices of their output. Starting from such a low base, capitalist production remained viable and with cheaper goods than their militarized counterparts, the logic of economic competition began to overwhelm the logic of military competition. The Japanese and West Germans, by engaging in capital intensive forms of investment, cut world profit rates, while raising their own national share of world profits. Their increased competitiveness in export markets forced other capitalist states to pay, with falling rates of profit, for the increased Japanese and German organic compositions of capital. But this, in turn, put pressure on these other capitalists to increase their competitiveness by raising their own organic compositions. The falling profit rates of the 1970s were the result. By 1973, the rates were so low that the upsurge in raw material and food prices caused by the boom of the previous two years was sufficient to push the advanced Western economies into recession. When governments reacted by trying to boost demand with budgetary deficits, firms did not immediately respond by increasing investment and output. State-sponsored spending merely increased the levels of existing prices without stimulating economic activity. Stagflation soon set in, heralding the defeat of Keynesian policies. LessonsWe can draw important lessons from the demise of Keynesianism. The failure of government spending in the 1970s to prevent a recession highlights the fact that in a capitalist economy, it is profitability that drives investment and when profitability drops, investment in the means of production and in labour will contract, leading to unemployment and loss of consumer incomes and demand. Hence, Keynesianism will work in the contemporary world only if it will increase the rate of profit. This is clearly not the case. Today, we have financialized capitalism, dominated by internationally mobile finance which constrains the ability of nation states to engage in demand management policies that would mitigate slumps. Financial markets can punish most effectively any economic policies they do not like, by causing capital flight that creates external and internal economic crises. So governments find it much more difficult to intervene to shore up domestic demand or to put in place policies that would lead to more equal distribution of income and assets. Since finance capital is perceived by governments to abhor fiscal deficits and resent higher rates of taxation, it constrains public expenditure that could directly and indirectly increase employment and economic activity in the system as a whole. Financial interests are against deficit-financed spending by the state for a number of reasons. First, deficit financing is seen to increase the liquidity overhang in the system, and therefore as being potentially inflationary. Inflation is anathema to finance since it erodes the value of financial assets. Second, financial markets fear that the introduction of debt-financed spending - which is driven by goals other than profit-making - will render interest rate differentials that determine financial profits more unpredictable. Third, if deficit spending leads to a substantial build-up of the state’s debt, it may intervene in financial markets to lower interest rates with implications for financial returns. Financial interests wanting to guard against that possibility tend to oppose deficit spending. Given finance capital’s aversion to an expansionary fiscal policy, Keynesianism is unlikely to be workable in the current context. As long as the big banks and capitalist monopolies rule over the state, full employment, a welfare state and so on are only dreams. What is needed is to openly confront the neoliberal state to fundamentally change the laws under which the economy operates: to systematically carry out a process aimed at eliminating the anarchy of capital accumulation; to take over the banks and big businesses and put them under a rational plan of production; in short, to carry out the socialist transformation of society. This is the only viable alternative. AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Midwestern Marx's Editorial Board does not necessarily endorse the views of all articles shared on the Midwestern Marx website. Our goal is to provide a healthy space for multilateral discourse on advancing the class struggle. - Editorial Board |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed