|

One of the chapters (incomplete) in Engels' 'Dialectics of Nature' is entitled: 'The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man'. Although this was written in the 1870s it compares well, I think, with scientific ideas that are considered new today. I propose to compare Engels' views with those reported by Ann Gibbons in an article in the June 15, 2007 issue of Science ('Food for Thought: Did the first cooked meals help fuel the dramatic evolutionary expansion of the human brain?'). This article is primarily about Harvard primatologist Richard Wrangham's theory that cooking led to the expansion of the human brain, that is, the Homo erectus brain, and resulted in the intellectual development of Homo sapiens. Wrangham, Gibbons says, 'presents cooking as one of the answers to a long standing riddle in human evolution: Where did humans get the extra energy to support their large brains?' That is, how do we explain that while we use about the same metabolic energy (calorie burning) as apes of comparable size, 25% of our energy is used by our brain, the apes only use 8% for theirs. Gibbons reports that a classical explanation is that by eating meat we shrank our gastrointestinal system (we need more guts to digest plants than meat, and it takes longer) and the saved energy was devoted to the brain. 'That theory,' she says, 'is now gathering additional support.' I don't know why she calls it 'classical' because she dates it to 1995. She writes, 'Called the expensive tissue hypothesis, this theory was proposed back in 1995....' Here is Engels (who is really 'classical') in the 1870s writing about the effects of a meat diet 'shortening the time required for digestion.' Engels said, 'The meat diet, however, had its greatest effect on the brain, which now received a far richer flow of the materials necessary for its nourishment and development, and which, therefore, could develop more rapidly and perfectly from generation to generation.' In this respect, modern science has not improved on Engels! Wrangham, Gibbons reports, 'thinks that in addition, our ancestors got cooking, giving them the same number of calories for less effort.' Wrangham first 'floated this hypothesis' way back in 1999 (Science, 26 March 1999, p. 2004). There is nothing new under the Sun. Here, again, is Engels: 'The meat diet led to ... the harnessing of fire [which] ... still further shortened the digestive process, as it provided the mouth with food already, as it were, half-digested....' Modern science is repeating the views of Engels, and the science of his day, a hundred and thirty years on. Engels talks about the role of labor in the transition from ape to man, and we shall see that it is labor that is the basis, in humans, for meat eating and cooking. But first, some more of Gibbons. If cooking led to the expansion of the brain (the modern way of talking about the transition from ape to man), when was the First Supper? Wrangham thinks it was about 1.6 to 1.9 million years ago [mya] and the diner as well as the chef were Homo erecti. Of course, Engels knew nothing of modern primate evolution or what a Homo erectus was, but he did think meat eating and cooking were gradually developed from ape like ancestors (along with speech and more complex thinking), so he would not have been surprised by modern theories. The article points out that early humans (e.g., australopithecines, 4 to 1.2 mya) had chimpanzee sized brains, while H. erectus (AKA H. ergaster) had a brain twice that size (c. 1000 cc). We evolved, along with our cousins the Neandertals, around 500,000 to 200,000 years ago, with brain sizes of about 1300 cc and 1500 cc, respectively. It was meat that allowed the skull to expand for brain growth 'according to a long-standing body of evidence.' A very long standing body of evidence since it is found in Engel's article. We are told the first stone tools, used to butcher animals, date from 2.7 mya in Ethiopia (at Gona). The cut marks on bones, adjacent fossils, etc., suggest that australopithecines were making these tools and eating meat. Wrangham thinks that H. erectus replaced raw meat with cooked meat (1.9 mya) and this accounts for the big increase in its brain size. The problem with this theory is that evidence of human use of fire only dates from about 790,000 years ago in what is now Israel. However, this is not fatal to Wrangham's position. Evidence of human controlled fire is very hard to come by and it is quite possible that earlier evidence of fire use will be found. Some other scientists think Wrangham is right in principle, cooking led to brain increase (as Engels said), but his timeline is off. It didn't happen by H erectus, but by H sapiens and Neandertals. The jury is out. While the jury may be out on Wrangham, it is not out on Engels. While this article discusses meat and cooking and the theory that 'cooking paved the way for brain expansion', it mentions nary a word about the role of labor in expansion of the human brain. The real point of Engel's article should be reaffirmed. Meat eating and cooking are secondary developments derivative of what Engels called 'the decisive step in the transition from ape to man.' This was the development of the human hand as a result of the evolution of erect posture in our ancestors. Once the hand was no longer used in locomotion, it was free to develop greater dexterity which 'increased from generation to generation'-- i.e., was selected for. 'Thus,' 'Engels writes, 'the hand is not only the organ of labour, it is also the product of labour.' As the first hominids developed more dexterity they began to make tools and to live under more complex social arrangements, necessitating better communication skills. Thus Engels writes, 'First labour, after it and then with it speech--- these were the two most essential stimuli under the influence of which the brain of the ape gradually changed into that of man, which for all its similarity is far larger and more perfect.' I have already mentioned above how Engels saw the adoption of meat eating and fire (cooking) as outgrowths of the labour of primitive humans in tool making (which led to hunting and fishing) which derived from the adoption of upright posture. The Australopithecines of Goma represent the earliest tool makers (hominid, that is) and if meat eating led them to develop into H. erecti, and Wrangham proves right and H. erectus was the first cook, and the H. erecti, through the use of fire and cooking, then developed into us, then modern science has validated the argument presented by Engels in his essay of the 1870s. The prescience of Engels demands that we in the 21st Century continue to profit and learn from his writings. He closes his essay with words that are even more relevant to us today than they were two centuries ago. After tracing the development of civilization from the time of the transition to modern humans, Engels writes about how our species thinks that it is the master of nature and that we can remake the natural world to our own specifications. But we have to be 'reminded that we by no means rule over nature like a conqueror over a foreign people ... all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly.' But will we apply them correctly? For that we must rely upon science and it doesn't look like our political and economic leaders are willing to do that, nor do the masses of people seem properly educated as to this necessity. Engels says that while we have built up a modern civilization (industrial capitalism) by subjecting nature to our immediate interests, we have not calculated the remote long term effects of our actions. 'In relation to nature, as to society, the present mode of production is predominately concerned only about the immediate, the most tangible result....' As long as the corporations are making their profits, as long as they sell their commodities, they do not care 'with what afterwards becomes of the commodity and its purchasers. The same thing applies to the natural effects of the same actions.' So, here we are 130 years down the line with global warming, polluted air, mass extinctions in the plant and animal worlds facing us, and the oceans slowly dying. Engels had hoped that we would by now have had a world socialist community and these problems would not be facing us. But we don't and they are. There is only one way to solve them, according to Engels, and it 'requires something more than mere knowledge. It requires a complete revolution in our hitherto existing mode of production, and simultaneously a revolution in our whole contemporary social order.' We had better get to work. Time is running out! AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. this article was produced by ecosocialism Canada. Archives January 2022

2 Comments

Image: CPUSA. A socialist moment has sprouted up on the American landscape and is beginning to take firm root, as most recently evidenced by India Walton’s stunning victory in working-class Buffalo. While not yet a trend, Walton’s election continues the spate of left candidates’ victories in Congress, state legislatures, and city councils across the country, reflecting a deep discontent in the body politic. In a word, America is growing more radical. But what is the meaning of this word that falls so easily from our lips? Radicalization is an objective process born out of the class struggle and capitalist crisis. Yet, like all objective processes, it has subjective ripples. These eddies, while influenced by basic class conflicts, are not limited to them. As a result, different people are radicalized for different reasons. The environment, police violence, sexism, and other forms of gender discrimination, the treatment of animals, in addition to poverty, racism, immigrant rights, voter suppression, unemployment, and discrimination on the job can lead to folks seeking deeper, more radical solutions. In general, the communist movement welcomes the growing radicalization of the broad public, particularly its working-class majority. It means people are waking up. But after getting out of bed, do folks step to the right or to the left? This is an issue often dismissed as a “war over words,” since the word “radical” literally means “to the root.” But the roots, indeed, the entire tree of radicalization has many branches. And the winds of change blow them in myriad directions. Today, in bourgeois discourse, anything to the left or right of the political or religious center is often labeled “radical” by the ruling-class hegemony. This war of words should not be dismissed — it’s an important part of the ideological struggle. For example, in the mainstream media, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is often referred to as “radical,” along with the right-wing “radicals” who attacked the Capitol earlier this year. On the other hand, the Republicans in Congress attack Medicare for All for being a “radical socialist demand” while condemning Black Lives Matter marches as the product of “radical anarchism.” Here a class analysis is helpful in determining what’s really radical, that is, what actually goes to the root, and what doesn’t. For us, policies that get to the root of solving the problem of working-class exploitation and promote greater equality and democracy are radical. Simply put, those that don’t are not. Suppressing the vote isn’t radical — it’s deeply conservative. Neither is opposing marriage equality. On the other hand, proportional representation, a voting method that could greatly expand democracy for minority parties, is a positive, radical democratic demand. Historically, as capitalism became a world system and grew into imperialism, the radicalization of the broad working-class public led to the creation of what’s called the world revolutionary process. Frustrated and angered by inequality and exploitation, middle- and working-class forces formed unions and political parties to press forward their just demands and interests. The October Revolution was born out of this struggle and brought with it a new stage in the process, the period of the transition from capitalism to socialism. There is also a worldwide counter-revolutionary process at work that has led to world wars, as well as regional and local armed conflicts. It has promoted repression and the growth of fascism. U.S. imperialism is one of the leading, if not the leading sponsors. The Trump movement and its international counterparts are contemporary examples of these efforts. Notwithstanding important differences on domestic policy, the Biden administration’s policy toward China and Venezuela continues the anti-socialist drive. Today’s radicalization process is drawing millions . . . some toward revolutionary Marxism. On the other side of the class and democratic ledger, a deep and thoroughgoing radicalization process is at work today in the U.S. Beginning first with Occupy Wall Street, followed by the movements for Black lives and the mass protests led by women in the initial days of the Trump administration, today’s radicalization process is drawing millions into its various orbits, some of whom are, as if by the very force of gravity itself, drawn toward the working-class and revolutionary Marxism. It has crystallized in what we’ve called the socialist moment. Communists highly value the growth of these radical democratic trends. Their contributions, new ideas, and victories are very important. Those trends that gravitate toward the working class and Marxism are adding fresh forces along with new opportunities and challenges. One of the challenges is the growth in the influence of what might be termed “middle-class” or “petty bourgeois radicalism.” By middle-class radicalism is meant a rather eclectic set of ideas and practices that historically have their origins in this strata’s frustration and primitive rebellion. Pressed on all sides and stuck between capitalism’s two main classes, the petite bourgeoisie’s class aspirations are crushed time and again. Viewing the world from a frog’s perspective — always looking up — they are ever being pushed down into the ranks of the working class. Their political practices and outlook are largely shaped by these conflicted conditions of life. Absent the experience of working in large groups and being forced to collectively bargain, they tend to seek basic change along narrow, individual paths as opposed to seeing the need for moving masses in struggle, an outlook that lends itself to anarchism, individual acts of terrorism, and an unfounded confidence in the actions of small groups and self-styled “vanguards.” Some tend to be anti-corporate but not yet anti-capitalist, “anti-establishment” but out of touch with working-class needs, modalities, and political imperatives. Middle-class radicalism is a mass concept and political trend. As a result, these trends run up against and counter to the realities of struggle, a reality that is framed today by the broad democratic fight against the fascist danger. Mass electoral movements of both right and left are defining characteristics of these days and times, but the need to build political majorities for real change, particularly in the electoral arena, is largely lost on this trend, disdained in favor of allegedly more militant, revolutionary action such as abstract calls for general strikes regardless of whether or not the conditions for such important actions exist. Middle-class radicalism should be treated not so much as the expression of this or that individual or organization but rather as a mass concept and political trend, one that rises and falls in tempo with the class, democratic, and anti-imperialist struggles both domestically and worldwide. Needless to say, each episode brings with it the unique features of the political terrain on which it’s born. For example, after the defeat of the McCarthy period in the 1960s, the labor left was confronted with the growing influence of radical middle-class strata who were approaching but had not yet reached consistent working-class positions. These forces viewed Marxism-Leninism as old hat, the communist parties as outmoded, the working class as no longer revolutionary, unity an unrealistic watchword, and the class struggle a pipe dream. Inspired by the likes of Régis Debray, Herbert Marcuse, and others, they sought to forge a New Left, with new sources of revolutionary activity. Regarding their class backgrounds, CPUSA leader James E. Jackson wrote, “They have come to the party out of the non-proletarian classes … from the poor workers in agriculture and the urban petite-bourgeoisie — the students, the intellectuals, the professionals.” Applauding this development, Jackson also warned of potential conflicts: It is a welcome sign of the times that the petty-bourgeois militants — from the cities or countryside — enroll in movements of mass actions and the best among them come to the party. At the same time, they generate mass pressure and constitute the primary source for the current attacks upon vital features of the Communist Party’s policies in the spheres of ideology, organization and tactics. Today a new wave of radicalism is presenting itself in a climate quite different from the one that was confronted by Jackson and his comrades. Importantly, a new, New Left is once again emerging. The difference is that its roots now are closer to the working class and people’s movements. This is due, in part, to the class’s changing composition. Sections of the population once considered middle class have become “proletarianized,” that is, pushed into the working class. At the same time, a wider section of the working class have access to higher education and have become politically literate. Add to this the increase in women, people of color, and of course the growth in the service sector, and you have a very different situation indeed. Thus the problem today is not so much the influx of middle-class elements but the remaining influence, that is, the residue of petty-bourgeois ideology, a problem exacerbated by the relative weakness of the Marxist left and the growth of the internet. The impact of this residue should not be underestimated. With respect to ideological trends it reflects the ongoing impact of remnants of Maoism, Trotskyism, and to varying degrees strands of anarchism. What, then, are the main challenges presented by middle-class radicalism?

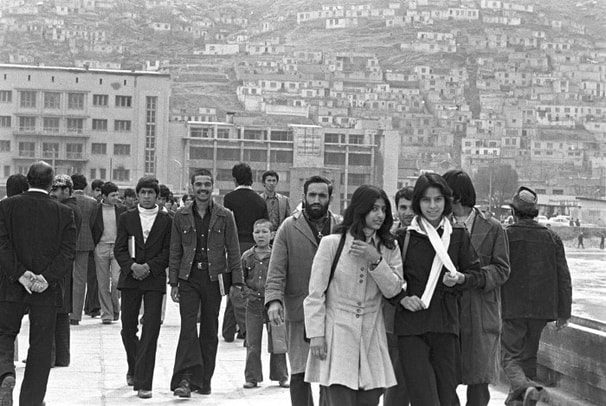

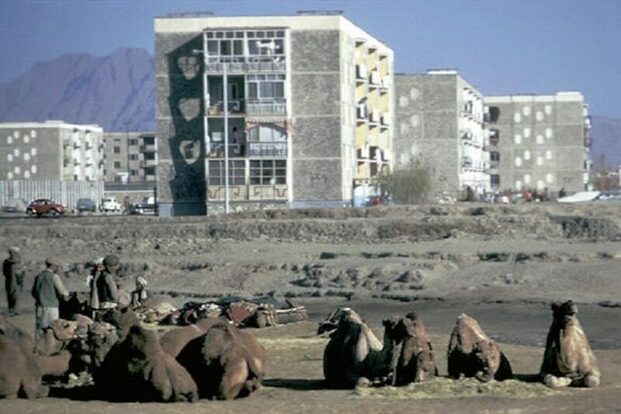

It’s inevitable that each generation’s initial imbibing of Marxism not only is shaped by the conditions and influences of the times but also is necessarily incomplete due to newness itself. During the wave of radicalization that swept Russia at the beginning of the 20th century, for example, Lenin complained of Marx and Engels’ doctrine being learned in an “extremely one-sided and mutilated form.” In the U.S. during the radical ’60s, one-sided interpretations repeated themselves, this time influenced not only by the New Left but also by a middle-class radicalism of a special type in the form practiced by the Mao leadership in China. On the other hand, the problem is exacerbated by the relative state of the communist movement itself. After the collapse of what was called “really existing socialism” due to right pressures, a serious ideological crisis and disintegration occurred within the communist movement. In response, there were manifest tendencies to over-correct to the left. These right and left opportunist swings exist to this day, in response to conditions on the ground and the communist’s relative maturity in addressing them. As Gus Hall pointed out, middle-class radical leftist errors cannot be effectively addressed unless right mistakes are corrected as well. In this regard, slowness in recognizing and responding to new circumstances contributes to the problem. One of the criticisms of the Communist Party from emerging young revolutionary forces is its approach to united front policy, electoral politics, and fighting the extreme right. Here, an understanding of the party’s correct policy with respect to fighting the fascist danger was somewhat confounded by its not taking initiative and fielding its own candidates. As a result, the CPUSA was accused of tailing the Democratic Party. In this regard, a long overdue decision to run communist candidates for office was taken recently by the CPUSA National Committee. With respect to tactics, it is vitally important to have an accurate assessment of where the struggle is at any given point in time. Tactics, as Gus Hall used to say, is timing. Take for example the issue of prison abolition and defunding the police, two important slogans that emerged in the fight against racist police murder. The key question is when and how these end goals can be obtained. Communists understand that the prison-industrial complex and the police force are institutions of the capitalist state. Our long-term vision anticipates the “withering away,” to use Marx’s phrase, of the state. This includes the socialist state as well. That’s what communism is all about: human freedom. How, then, is it possible to build a mass movement powerful enough to bring this about? The end goal has been established — are there way stations along the route, radical reforms that will take us, a quarter or one-half the way there? Of course there are. An approach advanced by ourselves and others, most notably the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, believes that the election of civilian control boards is one such step. We believe that the fight for such institutions is an important part of the fight for democracy and working-class empowerment. Think about it: These community boards would control hiring, firing, funding, the whole nine yards. They would help create conditions where alternatives to policing could be enacted, including the allocation of money to do so. This approach was often attacked by those who do not believe defunding the police is a “radical” enough step at this point in time. But why pit one goal against a step in the direction of achieving it? This relationship between means and ends is an ongoing tension in almost every arena. Maximum goals are placed over and against partial means for achieving them. In the fight for health care, a national health service is prioritized over Medicare for All; in the fight to end the Afghan war the demand to “Bring the troops home now” is placed against setting a date; and in the battle to end racist policing, abolition is posed as more revolutionary than the “reformist” position of community control. Mastering the relationship between reform and revolution. At bottom, what’s at stake here is mastering the relationship between reform and revolution. The issue is always how does the working-class and people’s movement marshal the forces necessary to achieve its goals. The promised land is over there on the hill, right across that river. How do we build a bridge to get there? Today the struggle for advanced democracy, that is, advanced democratic reforms, is that bridge. This raises the issue of what Marxist-Leninists regard as the fight for “consistent democracy” — the need to take consistent working-class positions with respect to the interests of the class as a whole. Because our working class is multi-racial and multi-gendered, a revolutionary party must champion the special measures necessary to address the demands of each section of the class, the racially and sexually oppressed in particular, including advanced democratic ones, like community control. A failure to do so weakens the fight for class unity with potentially devastating consequences. The middle-class radical chafing at community control steps away from taking consistent working-class positions. Objectively, it weakens the ability of people of color to have control over their lives. Another example of the failure to take consistent democratic positions is the Trotskyist critique of the 1619 Project, which locates racism at the very founding of colonial America. They claim 1619 is a disunifying Democratic Party capitulation to “identity politics.” But disunifying to whom? What kind of unity can be built on denying the slave trade and the genocide against Native Americans and their presence in the very DNA of the colonial republic? To paraphrase Marx here, labor in white skin cannot be free while labor in the black skin is bound and branded by historical cover-ups and lies. These questions over and again raise the issue of what it’s going to take to bring about “radical” change to this country. Where and when will the tipping point be reached? As dialectical materialists, we cannot be too speculative about how deep the capitalist crisis can get. We do know that it’s going to take a broad working-class and people’s unity to bring about real change. “Unity, united front” as Gus Hall writes, “are class-mass concepts.” In the past, middle-class radicals did not, he argued, “see themselves as being exploited or oppressed as a class. They do not react to oppression as a class.” The good news as we’ve argued above is that this is changing. Today there’s a greater recognition of common class and democratic interests. And on the slopes of that momentous change lives hope. Let’s build bridges to the future together, keeping ever present our cherished goals while collectively exploring how to get there. While doing so, the role of our revolutionary party is to help drive the radicalization process towards unity and socialist consciousness, that is, towards the working class and working-class power. AuthorJoe Sims is co-chair of the Communist Party USA (2019-). He is also a senior editor of People's World and loves biking. This article was republished from CPUSA. Archives June 2021 "Revolution is, unfortunately, not made with fastings. Revolutionaries from all parts of the world must choose between being the victims of violence or using it. If one does not wish to see one's spirit and one's intelligence serving brute force, one must forcibly resolve to put brute force under the subservience of intelligence and the spirit." The author of this passage, written more than forty years ago, was Jose Carlos Mariátegui, founder of the Peruvian Communist Party, a physically feeble man of unstable health who combined a powerful, cold and lucid intelligence with an exquisite artistic sensitiveness and an incorruptible revolutionary morale. His short life, ended before he was thirty-five, elapsed between long periods of hospitalization and poverty. Jail and the continuous humiliations he suffered, did not deter him from accomplishing his life's work, which, given the circumstances he had to cope with, does not cease to stimulate today more and more amazement, as well as the increased attention and admiration of revolutionaries the world over. Suffering from the time he was seven years old from an incipient physical disability which denied him a normal childhood, and when called upon, helping his mother out by working as proofreader in a publishing house, his career as a revolutionary writer began when an army man cowardly attacked him for the ideas he expressed in a newspaper article. The sum total of Mariátegui's work constitutes an ideological struggle against reformism, first and foremost. His work Defense of Marxism is imbued with this spirit, and the very founding of the Peruvian Communist Party denounces "domesticated socialism": "The ideology we adopt," states Mariátegui in his thesis of affiliation with the Third Internationale, "is that of militant revolutionary Marxism-Leninism, a doctrine which we wholly and unreservedly adhere to in its philosophical, political and socio-economic aspects. The methods we uphold are those of orthodox revolutionary socialism. We not only rebuke in all their forms the methods and tendencies of the Second Internationale, but oppose them actively." In this document he did no more than ratify before the world what he had previously made known in a magazine: "The political sector with which I can never come to terms is the other one: that of mediocre reformism, of domesticated socialism, of Pharisaical democracy. Moreover, if the revolution demands violence, authority, discipline, I am all for violence, authority, discipline. I accept them in block form, with all their horrors, without any cowardly reserves." Between 1919 and 1923 Mariátegui made a tour of Europe. It was in Italy where his thought ripened and became richer. In addition to his admiration for the theorist of violence, the revolutionary trade-unionist George Sorel, there was his passion for Gobetti, Labriola, and he found in Croce a friend with whom he could enter into controversy. Mariategui was an eyewitness to the great social upheavals which foreshadowed the triumph of Nazism and the reformist preachings of class collaborationism. On his return to Peru, in a work on the world crisis and on the role that the Peruvian proletariat ought to play in it, he wrote: "..The proletarian forces are divided in two great groupings: reformists and revolutionaries. "There is the faction of those who want to bring about socialism by collaborating politically with the bourgeoisie; and the faction of those who want to bring about socialism by conquering for the proletariat in its entirety political power." To this global crisis, Mariátegui answered in a vein both aggressive and critical: "I am of the same opinion as those who believe that humanity is going through a revolutionary period. And I am convinced of the imminent decline of all the social-democratic theses, of all the reformist theses and of all the evolutionist theses." In another article, he denounced the impotence of reformism to avoid war: "The thought of Lasallean social-democracy guided the Second Internationale; that is why it proved itself impotent before war. Its leaders and sectional corps had become accustomed to a reformist and democratic attitude and resistance to war demanded a revolutionary attitude." Defense of Marxism (a work from which we publish here one of its most interesting chapters) constitutes a rebuttal of Beyond Marxism by the Belgian revisionist Henri de Man, and of other social-democratic theorists, such as Vandervelde, a rebuttal which arises from revolutionary tenets and from practical positions. Mariátegui, who is brought to task in a controversy over principles, is equally removed from all sectarian and dogmatic standpoints, because he understood that Marxism was never "a set of principles embodying rigid consequences, similar in all historical climes and all social latitudes." "We must strip ourselves radically of all the old dogmatisms," he wrote, "of all the discredited prejudices and archaic superstitions." It is the correct interpretation of Marxist theory that makes him state directly: "Marx is not present in spirit in all his so-called disciples and heirs. Those who have carried on his ideas are not the pedantic German professors of the Marxist theory of value and surplus value, incapable themselves of making any contribution to the doctrine, devoted only to fixing limitations and labels to it; it has rather been the revolutionaries, slandered as heretics..." A deplorable article by Mirochevsky, published in Dialéctica, in which Mariátegui is grossly characterized as a petty bourgeois populist,was later impugned by the articles on Mariátegui of Semionov and Shulgovski, both of whom see the great Peruvian Marxist in a totally different light. But even today there are people interested in misrepresenting his political thoughts and actions to the point of belittling his significance from the Liberation Army spokesman he is to that of a sort of moralizing Salvation Army sermonizer. With each passing day, though, this task grows more difficult. In this chapter, "Ethics and Socialism," transcribed from his work Defense of Marxism, Mariétegui comes to grips with revolutionary ethics, with the ethics of socialism. For the great Peruvian, Marxist revolutionary ethics "does not emerge mechanically from economic interests; it is formed in the class struggle, carried on in a heroic frame of mind, with passionate willpower." And further on, he adds: "The worker who is indifferent to the class struggle, who derives satisfaction from his material well-being and, generally speaking, from his lot in life, will be able to attain a mediocre bourgeois moral standard, but will never be able to raise himself to the level of socialist ethics." The charges that have been brought to bear against Marxism for its attributed unethicality, for its materialistic motives, for the sarcasm with which Marx and Engels deal with bourgeois ethics in their pages, are not new. Neo-revisionist critique does not say, as regards this matter, one single thing which socialist Utopians and all the run of the mill Pharisaical socialists have not said beforehand. But Marx's reinstatement, from the standpoint of ethics, has also been effected by Benedetto Croce — being one of the most fully recognized representatives of idealist philosophy, his judgments will seem to all concerned to carry more weight than any Jesuitic regret over the petty bourgeois mentality. In one of his first essays on historical materialism, confusing the thesis of the lack of ethics inherent in Marxism, Croce wrote the following: "This current has been principally determined by the necessity in which Marx and Engels found themselves, before the various strains of socialist Utopians, of stating that the so-called social question is not a moral question (i. e., according to how it should be interpreted, this question will not be solved by preachings or by moral means), as well as by their severe criticism of class hypocrisy and ideology. It has also been nurtured, as far as I can see, by the Hegelian origin of the thoughts of Marx and Engels for it is known that in Hegelian philosophy ethics loses the rigidity which Kant gave it and which Herbart was later to lend support to. And, finally, the term "materialism" does not surrender in this connection a shred of efficacy, seeing that the mere term brings immediately to mind the full implications of what is meant by "interest" and "pleasure." But it is evident that the ideality and absoluteness of ethics, in the philosophical sense of such words, are necessary assumptions of socialism. Isn't the interest that drives us to create the concept of surplus value a moral or social interest, or whatever term might be used for defining it? In the sphere of pure economic science can one speak of the theory of surplus value? Doesn't the proletariat sell its productive capacity for what it's worth, given its situation in present day society? And, without this moral assumption, how can the tone of violent indignation and bitter sarcasm, along with Marx's political actions, contained in every page of Das Kapital, be accounted for?" (Materialismo Storico ed Economia Marxistica). I have previously had occasion to set forth this passage from Croce, which led me, in turn, to quote some phrases by Unamuno, in his work entitled The Agony of Christianity (La agonía del cristianismo) and which consequently made me the recipient of a letter by Unamuno himself, who wrote me therein that Marx was more truly a prophet than a professor. On more than one occasion Croce has quoted verbatim the passage referred to above. One of his critical conclusions on this subject la precisely "the negation of the intrinsic amorality or of the anti-ethicality of Marxism." And, In this same text, he wonders why no one "has thought of calling Marx, in the way of extending him a further honor, the Machiavelli of the proletariat," a fact which can be thoroughly and amply explained in the light of the conceptions he formulates in his defense of the author of The Prince, who was no less persecuted by regrets of which posterity made him the victim. On the subject of Machiavelli, Croce has on that he "discloses the necessity and autonomy of politics, which is beyond moral good and and the laws which it would be of no consequence at all to rebel against, which are immune to sort of exorcism and which cannot be made to take leave of the world with the aid of holy water." In Croce's opinion Machiavelli gives evidence of being of "a divided mind and spirit on politics, of the autonomy of which he has become aware, and he now thinks of it as a corrupting influence for compelling him to sully his hands in dealing with basely ignorant people, and now as a sublime art with which to found and uphold that great institution, the State" (Elementi di politica). The similarity between these two cases has been clearly pointed out by Croce in the following terms: "A case, in some respects analogous to that around which the discussions on Marxian ethics have centered, is the one having to do with the traditional critique on the ethics of Machiavelli; a critique which was brought to fruition by De Sanctis (in the chapter concerning Machiavelli in his Storia della litteratura), but a critique which nevertheless recurs quite systematically, and in a work by Professor Villari, one reads that Machiavelli's great imperfection is to be found in the fact that he did not propound the moral question. And I have often asked myself if Machiavelli was bound by contract or in any way obliged to deal with every sort of question, including those in which he took no interest and on which he had nothing to say. It would be tantamount to reproof of those who study chemistry for not delving into the metaphysical principles of matter." The ethical function of socialism —in regard to which the hurried and summary extravaganzas of Marxists such as Lafargue, no doubt make for error— should be sought out, not in highfalutin decalogues nor in philosophical speculations, which in no way constitute a necessity in the formulation of Marxian theory, but in creating a morale for the producers by the same process of the anti-capitalist struggle. "Vainly," Kautsky has said "have the English workers been made the object of moral preachings, of a loftier conception of life, of feelings underlying nobler deeds. The ethics of the proletariat derives from its revolutionary aspirations; from them will it be endowed with more strength and elevation of purpose. That which has saved the proletariat from debasement is the idea of revolution." Sorel adds that for Kautsky ethics is always subordinated to the idea of the sublime, and though he disagrees with many official Marxists, who carried to extremes their paradoxes and jokes on the moralists, he nonetheless, concurs in that "Marxists had particular reasons for showing lack of confidence on all that which touched upon ethics; the propagandists of social reforms, the Utopians and the democrats had so repeatedly and misleadingly recurred to the concept of Justice that no one could be denied the right of looking upon all dissertations to this effect as a rhetorical exercise or as a sophistry, destined to lead astray those who were involved in the labor movement." One can ascribe to the influence of Sorel's thought Edward Berth's apologia on this ethical function of socialism. "Daniel Halevy," states Bert "seems to believe that the exaltation of the producer is bound to harm the man; he attributes to me a completely American enthusiasm for an industrial civilization But it will not be thus; the life of the free spirit is as dear to me as it is to him, and I am far from believing that in the world there is nothing else save production. It is always, in the end, the old charge levelled against the Marxists, who are held responsible for being both morally and metaphysically, materialists. Nothing could be more false; historical materialism does not impede in any way whatsoever the highest development of what Hegel calls the free or absolute spirit; quite the contrary, it is its preliminary condition. And our hope is, precisely, that in a society which rests on an ample economic base, made up by a federation of shops where free workers would be inspired by a spirited enthusiasm for production, art, religion and philosophy would in turn be given a prodigious impulse and the frantic and ardent rhythm resulting from it would simply skyrocket." Luc Dartin's sagacity, sharpened by a finely wrought characteristically French irony, throws light on this religious-like ascendancy pervading Marxism, a phenomenon which conforms to principles inherent in the constitution of the first socialist country in the world. Historically it had already been proven by the socialist struggles of the West, that the sublime, such as the proletariat conceives of it, is not an intellectual utopia nor a propagandistic hypothesis. When Henri de Man, demanding from socialism an ethical content, tries to demonstrate that class interest can not of itself become a sufficiently potent motor of the new order, he does not in any way go "beyond Marxism," nor does he make amends for things which have not already been pointed out by revolutionary criticism. His revisionism attacks revisionistic trade-unionism, in the practice of which class interest is content with the satisfaction of limited material aspirations. An ethics of producers, as is conceived by Sorel and Kautsky, does not emerge mechanically from economic interest, it is formed in the class struggle, engaged in with heroic disposition, with passionate will power. It is absurd to look for the ethical sentiments of socialism in those trade-unions which have fallen under the influence of the bourgeoisie — in which a domesticated bureaucracy has become enervated in its class consciousness — or in the parliamentary groups, spiritually assimilated by the class enemy, regardless of the fact of their combative stand before it as witnessed by their speeches and motions. Henri de Man expresses something which is perfectly superfluous and beside the point when he states: "The class interest doesn't explain everything. It does not create ethical motives." These avowals may impress a certain breed of nineteenth century intellectuals, whom, glaringly ignoring Marxist thought, glaringly ignoring the history of the class struggle, facilely imagine, as does Henri de Man, that they can surmount the limits of the Marxian school of thought. The ethics of socialism is formed in the class struggle. If the proletariat is to comply in its moral progress with its historical mission it becomes necessary for it to acquire beforehand a conscienciousness of its class interests; but in itself, class interest does not suffice. Long before Henri de Man, the Marxists have understood and felt this perfectly. Therein, precisely, arise their stalwart criticisms against lubberly reformism. "Without revolutionary theory, there is no revolutionary action," Lenin used to repeat, referring to the yellow-streaked tendency to forget historical finality in order to pay attention only to hourly circumstances. The struggle for socialism instills in workers which take part in it extreme energy and absolute conviction along with an asceticism that forcibly cancels and makes utterly ridiculous any charge levelled against them having to do with their materialistic creed, and formulated on behalf of a theorizing and philosophical ethics. Luc Durtain, after visiting a Soviet school, asked whether he couldn't find in Russia a lay school, to such an extent did he regard of a religious tenor Marxist education. The materialist, if it be one who practices and is religiously devoted to his convictions, can only be distinguished from the idealist by a convention of language (Unamuno, touching upon another aspect of the opposition between idealism and materialism, states that "since what is matter to us is no more than an idea, materialism is idealism"). The worker who is indifferent to the class struggle, who derives satisfaction from his material well-being and generally speaking, from his lot in life, will be able to attain a mediocre bourgeois moral standard, but will never be able to raise himself to the level of socialist ethics. And it is preposterous to think that Marx ever advocated, or ever wanted to separate the worker from his source of livelihood, or ever wanted to deprive him of all that which binds him to his work, so that the class struggle might take hold of him more firmly, more completely. This conjecture is only conceivable in those who abide by far-fetched Marxist speculations, as Lafargue, the apologist of the right, as the individual to idleness was wont to do. The mill, the factory, act on the worker's mind and soul. The union, the class struggle, continue and complete the worker's educational process. "The factory," Gobetti points out, "offers the precise vision of the coexistence of the social interests: the solidarity of labor. The individual grows accustomed to feeling himself part of the productive process, an indispensable as well as an insufficient part. Here we have the most perfect school of pride and humility. I will never forget the first impression the workers gave me, when I undertook a visit to the Fiat furnaces, one of the few English-like modern capitalistic enterprises in Italy. I felt in those workers a self-possessed attitude, an unassuming assertiveness, a contempt for every manner of dilettantism. Whomever lives in a factory possesses the dignity of work, the willingness for making sacrifices and the habit of resisting fatigue. A way of life severely founded on a sense of tolerance and interdependence which induces punctuality, strictness and perseverance in the worker. These virtues of capitalism are offset by an almost bleak asceticism; whereas, on the other hand, selfrestrained suffering nourishes, when exasperation sets in, the courage to fight and the instinct for taking a defensive stand politically. English adultness, the capacity for believing in precise ideologies, of undergoing perils in order to make them prevail, the unbending will power of carrying forward with dignity the political struggle, are born of this apprenticeship, the significant implications of which are ushering in the greatest revolution since the rise of Christianity." In this severe environment of persistency, of effort, of tenacity, the energies of European socialism have been forged, which, even in those countries where parliamentary reformism holds a big sway over the masses, offer Latin Americans an admirable example of continuity and duration. In different Latin American countries the socialist parties and the trade-union members have suffered a hundred defeats. However, each new year the elections, protest movements, any rally whatever, either of an ordinary or extraordinary character, will always find these masses greater in number and more obstinate. Renan recognized that which was mystical and religious in such a social creed. Quite justifiably Labriola praised German socialism: "This truly new and imposing case of social pedagogy, i.e., that in such great numbers of workers and middle class sectors a new conscience should take shape, in which equally coincide a guiding perception of the economic circumstance — a stimulant conducive to stepping up the struggle — and socialist propaganda, understood as the goal and arriving point." If socialism should not be achieved as a social order, this formidable edifying and educational accomplishment would prove more than enough to justify it in history. The previously quoted passage from de Man admits this postulation when he states, though with a different intention, that "the essential thing in socialism is the struggle in its behalf," a phrase which is very much reminiscent of those in which Bernstein advised the socialists to busy themselves primarily with the movement and not with the movement's results, by which, according to Sorel, the revisionist leader expressed a much more philosophical meaning than what he himself might have suspected. De Man does not ignore the pedagogical and spiritual function of the trade-union, though his own experience was inherently and mediocrely social-democratic. "The trade-union organizations," he observes, "contribute in a much greater measure than the majority of the workers suppose, and almost all of the employers, to binding together more vigorously the ties between the workers and their regular chores. They obtain this result almost without their knowing it, by trying to keep up qualification and efficiency and by developing industrial education, by organizing the right the workers have to union inspection and applying democratic norms to shop discipline by the system of delegates and sections, etc. In so doing, the union renders the worker a service a great deal less problematical, considering him a citizen of a future city, rather than seeking the remedy in the disappearance of all the psychological relations between the worker and the environment of the shop." But the Belgian neo-revisionist, notwithstanding his idealistic protestations, discovers the advantage and merit of all this in the increasing attachment of the worker to his material well-being and in the measure in which the latter factor makes a Philistine of him. Paradoxes of petit-bourgeois idealism! AuthorJuan Carlos Mariategui This article was republished from Marxists.org. Archives June 2021 4/16/2021 Afghanistan’s Socialist Years: The Promising Future Killed Off by U.S. Imperialism. By: Marilyn BechtelRead NowWomen attend a rally in Kabul in the late 1970s. | Imgur via Pinterest In the mid-1970s and early ’80s, People’s World correspondent Marilyn Bechtel was editor of the bimonthly magazine, New World Review. She visited Afghanistan twice, in 1980 and 1981. The article below first appeared in our pages on Oct. 6, 2001—the day before the U.S. launched its war in Afghanistan—under the headline, “Afghanistan: Some overlooked history.” With the Biden administration now withdrawing all troops from the country, we present this article as a reminder that the U.S.’ longest war had roots that went beyond the terrorist attacks of 9/11, stretching back to Cold War anti-communism. Since the horrific events of Sept. 11, much has been said about the desperate situation of the Afghani people now crushed under the heel of the theocratic, dictatorial Taliban, and about the role of the Northern Alliance and other Taliban opponents who now figure in Washington’s plans for the region. Kabul street scene, 1979. | TASS There has been talk, most of it distorted, about the role of the Soviet Union in the years from 1978 to 1989. There has been talk, most of it understated, about the role of the U.S. in building up the Mujahideen forces, including the Taliban. But almost no one talks about the effort the Afghan people made in the late 1970s and ’80s to pull free of the legacy of incessantly warring tribes and feudal fiefdoms and start to build a modern democratic state. Or about the Soviet Union’s role long before 1978. Some background helps shed light on the current crisis. Afghanistan was a geopolitical prize for 19th-century empire builders, contested by both czarist Russia and the British Empire. It was finally forced by the British into semi-dependency. When he came to power in 1921, Amanullah Khan—sometimes referred to as Afghanistan’s Kemal Ataturk—sought to reassert his country’s sovereignty and move it toward the modern world. As part of this effort, he approached the new revolutionary government in Moscow, which responded by recognizing Afghanistan’s independence and concluding the first Afghan-Soviet friendship treaty. From 1921 until 1929—when reactionary elements, aided by the British, forced Amanullah to abdicate—the Soviets helped launch the beginnings of economic infrastructure projects, such as power plants, water resources, transport, and communications. Thousands of Afghani students attended Soviet technical schools and universities. After Amanullah’s forced departure, the projects languished, but the relationship between the Soviets and the Afghans would later re-emerge. The Center for Science and Culture was built in Kabul as a gift from the people of the Soviet Union. Once U.S.-backed Mujahideen forces took power, the facility was destroyed. | TASS In the 1960s, a resurgence of joint Afghan-Soviet projects included the Kabul Polytechnic Institute—the country’s prime educational resource for engineers, geologists, and other specialists. Nor was Afghanistan immune from the political and social ferment that characterized the developing world in the last century. From the 1920s on, many progressive currents of struggle took note of the experiences of the USSR, where a new, more equitable society was emerging on the lands of the former Russian empire. Afghanistan was no exception. By the mid-’60s, national democratic revolutionary currents had coalesced to form the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). Modern apartment buildings constructed in Kabul in the 1980s with Soviet assistance. | TASS In 1973, local bourgeois forces, aided by some PDP elements, overthrew the 40-year reign of Mohammad Zahir Shah—the man who now, at age 86, is being promoted by U.S. right-wing Republicans as the personage around which Afghanis can unite. When the PDP assumed power in 1978, they started to work for a more equitable distribution of economic and social resources. Among their goals were the continuing emancipation of women and girls from the age-old tribal bondage (a process begun under Zahir Shah), equal rights for minority nationalities, including the country’s most oppressed group, the Hazara, and increasing access for ordinary people to education, medical care, decent housing, and sanitation. A Mujahideen Islamist fighter aims a U.S.-made Stinger missile supplied by the CIA near Gardez, Afghanistan, December 1991. | Mir Wais / AP During two visits in 1980-81, I saw the beginnings of progress: women working together in handicraft co-ops, where for the first time they could be paid decently for their work and control the money they earned. Adults, both women and men, learning to read. Women working as professionals and holding leading government positions, including Minister of Education. Poor working families able to afford a doctor, and to send their children—girls and boys—to school. The cancellation of peasant debt and the start of land reform. Fledgling peasant cooperatives. Price controls and price reductions on some key foods. Aid to nomads interested in a settled life. I also saw the bitter results of Mujahideen attacks by the same groups that now make up the Northern Alliance—in those years aimed especially at schools and teachers in rural areas. The post-1978 developments also included Soviet aid to economic and social projects on a much larger scale, with a new Afghan-Soviet Friendship Treaty and a variety of new projects, including infrastructure, resource prospecting, and mining, health services, education, and agricultural demonstration projects. After December 1978 that role also came to include the introduction of Soviet troops, at the request of a PDP government increasingly beset by the displaced feudal and tribal warlords who were aided and organized by the U.S. and Pakistan. The rest, as they say, is history. But it is significant that after Soviet troops were withdrawn in 1989, the PDP government continued to function, though increasingly beleaguered, for nearly three more years. Somewhere, beneath the ruins of today’s torn and bloodied Afghanistan, are the seeds that remain even in the direst times within the hearts of people who know there is a better future for humanity. In a world struggling for economic and social justice—not revenge—those seeds will sprout again. AuthorMarilyn Bechtel writes for People’s World from the San Francisco Bay Area. She joined the PW staff in 1986, and currently participates as a volunteer. This article was first published by People's World.

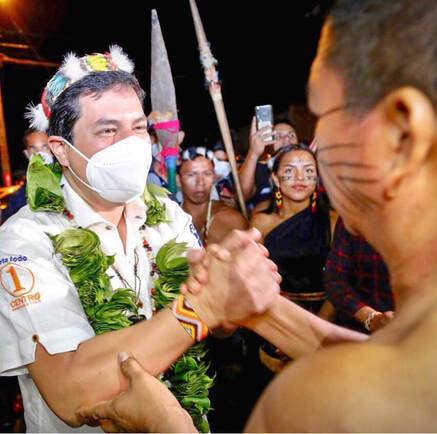

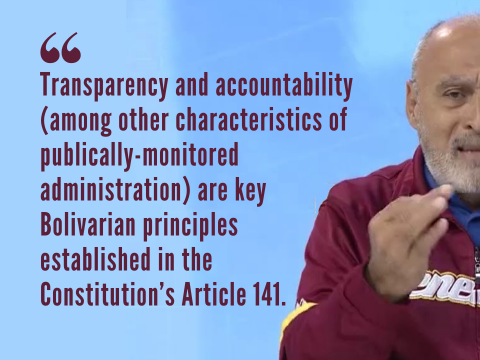

Ecuador's leftist candidate Andrés Arauz has won the first round of the country's presidential elections held on 7 February, 2021, garnering 31.5% of the vote. An economist and former minister in socialist president Rafael Correa’s government, he has led the ticket for the Union for Hope coalition - what was Alianza País headed by Correa before the party split in 2017. However, it appears that Arauz did not win by enough of a margin to avoid a second runoff, provisionally scheduled for April 11, 2021. The election has been marred by allegations of voter suppression, as Ecuadorians were forced to wait for hours in uncharacteristically long polling lines, especially in areas known to support Arauz. Political ArenaArauz faced two politicians - Guillermo Lasso and Yaku Pérez Guartambel. According to a quick count by the National Electoral Council (CNE), Pérez and Lasso took 20.04% and 19.97% of the votes, respectively. Lasso is the candidate for the conservative alliance “Creating Opportunities” (CREO). He is also a member of Opus Dei, banker and businessman. A true representative of the Ecuadorian oligarchy, he served as a minister of economy in the Jamil Mahuad government in 1999, which fell in the winter of 2000 at the hands of 2 million peasants and poor workers who took over the streets in protest against dollarization. Pérez is the candidate of the indigenous Pachakutik Party. While he portrays himself as an “eco-socialist”, many from the Correa camp have questioned his commitment to defend indigenous communities and remember that some factions of the Pachakutik Party have, in the past, opportunistically aligned with the right against Correa’s government. Moreover, he is also known for supporting US-backed right-wing coups in Latin America and wholeheartedly backing imperialism. CorreismoArauz’s electoral hegemony is explained by the strength of Correismo - the ideology based on the policies of Correa’s government. Between 2007 and 2017, Correa undertook a series of post-neoliberal counter-reforms, strengthening the state, increasing its regulatory and economic planning power, and broadening its social influence. Correa re-constructed Ecuador by way of a Constituent Assembly convened in 2007. In his inauguration speech on January 15 of the same year, he stated: “This historic moment for the country and the entire continent demands a new Constitution for the 21st century, to overcome neoliberal dogma and the plasticine democracies that subject people, lives, and societies to the exigencies of the market. The fundamental instrument for such change is the National Constituent Assembly”. The Constitution set out a social agenda whose essential axes are: (1) social protection aimed at reducing economic, social and territorial inequalities, with special attention to more vulnerable populations (children, youth, elderly); (2) the economic and social inclusion of groups at risk of poverty; (3) access to production assets; (4) universalization of education and health. To this end, inter-sectoral cooperation was initiated among the Ministries of Education, Economic and Social Inclusion (MIES), Agriculture, Health and Migration. The 2008 Constitution established the need to build a health system oriented toward comprehensive health care for the population, called the “Sectoral Health Transformation of Ecuador”, and created the “Model of Comprehensive Health Care”, which provided communal underpinnings to the approach toward healthcare. It is characterized by free health services for users, the deployment of sanitary infrastructure (hospitals and primary care centers) and training for health personnel. Buen VivirThe construction of the Ecuadorian State was based on “good living” (El Buen Vivir) - a conception which places life at the center of all social practices and includes the strengthening of the welfare state in order to guarantee it. Correa acolyte René Ramírez argues that buen vivir means: “free time for contemplation and emancipation, and the broadening or flourishing of real liberties, opportunities, capacities, and potentialities of individuals/collectives to bring that which society, territories, diverse collective identities, and everyone - as a human being or collective, universal or individual - values as key to a desirable life.” An essential part of buen vivir is communal action. While there were many gaps in the achievement of this aim, the Corriesta administration did try to start the “citizenization of political control” - the election of institutional and control authorities not by the legislature, but by an ad hoc organizational structure called the “Council of Citizen Participation and Social Control”. These measures were intended to establish a framework for participatory governance. Neoliberal OnslaughtLenin Moreno assumed presidency in 2017, riding on the back of Correa’s support. Having served as vice president (2007-13) in Correa’s government, he was expected to continue the progressive agenda of a strong welfare state. Instead, Moreno chose to comprehensively break away from the previous paradigm of anti-neoliberalism, persecuting Correa and his supporters. Moreno used a February 2018 referendum to destroy the CNE, the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court, the Judiciary Council, the attorney general, the comptroller general, and others. With the assistance of the CNE, Moreno divided and took control of Correa’s party. When the Correistas tried to re-organize themselves in a new party, the state blocked them. They said that the proposed names were misleading or that the signatures collected were invalid. By 2019, the Correistas used the “Social Commitment Strength” platform to run for local elections in 2019. This platform was then banned in 2020. The suppression of Correistas has occurred against a backdrop of a neoliberal onslaught. Moreno has followed laissez-faire economic policies, privatization, fiscal austerity, deregulation, free trade and state reduction promoted by the Washington Consensus. His initial actions aimed to incentivize private economic activity, including the elimination of advances on income taxes for firms and a move toward labor market flexibility. Further, Moreno introduced tax exonerations for firms that repatriated funds within the next twelve months. In August of 2018, the National Assembly approved the “Organic Law for Productive Development, Attraction of Investment, Employment Generation, and Fiscal Stability and Equilibrium”. This law included amnesty for any outstanding interest, fines, or surcharges owed to a number of government agencies. A 10-year income tax exemption was introduced for new investments in the industrial sector. Along the same lines, a 15-year exemption for investment in basic industries, and a 20-year exemption for investments located near the country’s border, were also specified in the bill. Exemptions were introduced to the tax on capital outflows for productive investments. These measures reduced the high-tax burden that private companies earlier faced. Moreno has announced many austerity adjustments: reduction in the salaries of many government functionaries, elimination of bonus payments for state employees, overall reduction in the number of public sector workers, and the sale of state-owned companies. All this resulted in the “October 2019 uprising”. Hope for SocialismIt is likely that Arauz’s socialist leanings will help him succeed in re-gaining presidential power. He is committed to rolling back Moreno’s neoliberal measures, standing firm against the ruthless demands of international capital, increasing public spending on education and healthcare, and imposing restrictions on capital flight. Arauz has conceived of a state model oriented towards selective economic interventionism for the benefit of the poor. This model argues that the people-centric acceleration of economies is not a spontaneous phenomenon that results exclusively from market forces, but is the result of vigorous state involvement in strategic sectors through planning and structural reforms in the context of a mixed economic system. Considering the fact that absolute poverty has tripled during Moreno’s 4-year presidency, Ecuadorians will elect a leader who promises to provide them with dignified lives. About the Author: Yanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Photo source: Andres Arauz' Instagram - @ecuarauz