|

3/18/2023 Exploring Friedrich Engels’ Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy: Part 3 – Feuerbach. By: Thomas RigginsRead Now(Read Part 1 HERE and Part 2 HERE) So what kind of Idealism is Feuerbach, according to Engels, peddling? Feuerbach is a materialist who wants to advocate a true religion for humanity. Here is a quote from him: “The periods of humanity are distinguished only by religious changes. A historical movement is fundamental only when it is rooted in the hearts of men. The heart is not a form of religion, that the latter should exist also in the heart; the heart is the essence of religion.” Religion is based on the love that humans are capable of sharing with one another. Heretofore that love has been objectified and projected upon mythical beings and has been the alienated essence of the historic religions as well as the natural religions of primitive times. Now, in the modern world of scientific understanding, we can dispense with the mythical superstitious religious beliefs that dominate the masses (they will have to be educated of course) and have a loving religion of the heart directly practiced by humans, Engels says, “this becomes the love between ‘I’ and ’Thou.’” Sex is the highest way we can express our love; so, sexual relations become one of the highest forms of Feuerbach’s new religion. Sexual attraction and love making are purely natural functions of the human being and they should not be circumscribed by the rules and regulations of the state or of the positive religions (positive = historically existing). All the rules and regulations about sex and the relations between loving humans that are associated with, for example, Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Buddhism should be dumped as they are based on illusions and mythological premises. But the Idealism that Feuerbach manifests comes from his view that these relations do need a religious foundation, not from the positive or primitive religions, but based on the “human heart.” Speaking strictly as a materialist, the “heart” is a muscle, just as the ischiocavernosus muscle, so Feuerbach is being metaphorical. Anyway, Engels says, the major point is “not that these purely human relations exist, but that they shall be conceived of as the new, true religion.” Here Feuerbach is a victim of his era: religion is important, and Feuerbach wants to keep the word around – he thinks it is important to have a society based on “religion.” Engels thinks it’s really ridiculous to try and have a materialist religion, one without a “God” or any supernatural ideas attached to it. The idea that religious changes are what delimit the periods of humanity is, Engels says: “Decidedly false.” For Marxists, As Engels notes, the great epochal changes in history are economically based on changes in class relations and power politics; religious changes only accompanied these events. Meanwhile, there can be no “I-Thou” lovey-dovey relationships between humans as humans based on the natural proclivity for people to love one another, this is because our world and the globalized society we are all living in is still “based upon class antagonism and class rule.” Feuerbach’s writings on the religion of love, Engels points out, are “totally unreadable today.” Religion remains in the 21st century what it has always been— the opium of the masses. We can work with religious people on specific progressive projects, but we should not encourage religious belief because such beliefs are rooted in Idealistic unscientific notions which prevent people from a proper understanding of reality – and this holds back the movement towards human liberation and in the long run only helps the exploiters. Despite his writings on religions, Feuerbach has only really studied one, according to Engels, i.e., Christianity. Not only that, but it is an abstract idealized form of Christian morality which Feuerbach thinks his new religion of the heart, based on sexual intercourse, will instill in humanity. What is this “humanity” that he writes about? It is an abstract and idealized humanity that Feuerbach finds existing in all ages and climes. It is an ahistorical concept – some kind of “human nature” that Feuerbach had deduced by his concept of Christian morality. Engels contrasts the materialist Feuerbach with the objective idealist Hegel, who also writes about Christianity and morals. Despite outward appearances, the materialist is really an idealist and the idealist a materialist. Feuerbach is a materialist because he doesn’t believe in God or a supernatural world on which to base his new religion; he bases it on the materially existing species of man on our planet and on nothing else. Sexual intercourse is at the heart of the heart of the new religion. It is really rooted in material existence. Yet his moral system is an abstract one deduced from an ideal Christianity. Christianity, Jesus, God, etc., is nothing more than a human reflection projected into the sky for Feuerbach – the human family Is the source of all the ideals about the Holy Family, morality is just this reflection coming back to us of our own dreams and ideals. But for Engels, this reflection is devoid of the actual behavior of Christians throughout history who, besides engaging in sexual intercourse, have done a lot of unsavory activities inspired by their religion. Feuerbach who “preaches sensuousness, immersion in the concrete, in actuality, becomes thoroughly abstract as soon as he begins to talk of any other than mere sexual intercourse between human beings.” So, the materialist has produced a philosophy based on abstract mental constructions he has deduced from the Christian religion which is the basis for his morality. This is why the materialist is an idealist! A living breathing unity of opposites. (At least until 1872). And what of Hegel? Was Feuerbach actually an improvement on Hegel? Well, here is Feuerbach’s morality in a nutshell. All human beings have an innate desire for “bliss;” but we can’t attain bliss without knowing how not to overindulge our desires, and we must also respect the social rights of others to also attain bliss – and this we do through love. Engels writes, “Rational self-restraint with regard to ourselves and love in contact with others— these are the basic rules of Feuerbach’s morality; from them all others are derived.” Despite all Feuerbach’s comments about materialism, these rules about morality are, Engels says, banal. You can’t find “bliss” by just thinking about yourself and it is impossible to practice “love” towards others in the real world due to the actual social and economic systems humans live in. Feudal lords and surfs, slaves and masters, and in our age capitalists and proletarians are proof of the banality of Feuerbach’s pretensions to morality. Ruling (and exploiting) and ruled (and exploited) classes existing under the same social totality means that the masses will always be deprived of the material needs they require – both to find a blissful life for themselves, or to properly be able to practice unselfish “love” for others, especially for those who oppress them. In this respect Hegel was more advanced than Feuerbach. Hegel saw morality as advancing through historical stages driven by humanity's “greed and lust for power.” Hegel explained how in each stage this struggle produced contradictions that could be resolved only by moving on to a higher stage of moral consciousness, until we reached Hegel’s day, when the idea of human equality had reached its highest bourgeois level (with the French Revolution) – all men are equal before the law (the level including women was yet to come). There was an innate drive here also, the struggle for human freedom – which was an idea struggling to come to human consciousness and history – was the result of this struggle. This was Hegel’s idealism. For Marxists, it will be the class struggle objectively working in the material life of human beings at any point in history that is responsible for “moral” progress. “The cult of abstract man, which formed the kernel of Feuerbach’s new religion, had to be replaced by the science of real men and their historical development. This further development of Feuerbach’s standpoint beyond Feuerbach was inaugurated by Marx in 1845 in The Holy Family.” [Although this work was a joint creation of Marx and Engels, Engels here credits Marx with the breakthrough beyond Feuerbach’s materialism to what was to become Dialectical Materialism.] Next: Part Four “Marx” AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives March 2023

0 Comments

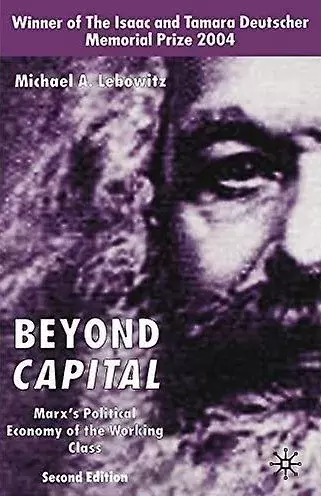

2/22/2023 Michael Lebowitz, Beyond Capital: Marx’s Political Economy Of The Working Class By: Madelaine MooreRead Now

Returning to the text in 2022, its unique take on some old Marxist questions as well as some weaknesses were more apparent. While some of the arguments working in the background to the book are of their time, in particular, the desire to offer a necessary Marxist antidote to the New Social Movement debates of the 1980s/1990s, many of Lebowitz’s arguments continue to press upon critical points in Marxist theory and have since been taken further by social reproduction theorists and others. Beyond Capital, first published in 1992 and then significantly revised in 2004, still offers a refreshing and critical intervention into why capitalism persists despite ongoing crises, and what is revealed when the working class is approached as subject instead of merely the object of capital reproduction and crisis. Underpinning these arguments is the age-old question of how to reconcile subjectivity and revolutionary consciousness with the abstract forces of capitalist reproduction. Lebowitz bases his argument on the premise that Marx’s Capital was an unfinished project. What is missing, he suggests, is the book on wage labour where Marx would have competed the totality of capitalist reproduction by offering the standpoint of wage labour, through which class subjectivity could be analysed. Yet without this book we are stuck with a one-sided Marxism where only capital is subject. Within this missing book we might find the theoretical foundations to explore how the economic and political are integral to one another, as well as how the intertwined processes of domination, expropriation, and exploitation operate through the living complex human being behind the abstract notion of labour power. Ultimately, Lebowitz is trying to guard against the argument that what drives capital is capital where struggle is an after effect. Although the way he develops his argument, in particular the need to find a perfect mirror or other to existing one-sided categories, can feel forced at times, and certain discussions for example on value and competition remain undeveloped, these are barriers that can (and have) been overcome by others, rather than limitations of the argument itself. Drawing out from the specifics, the overall purpose of Beyond Capital as a treatise against capitalo-centricism, and the steps he takes to get there continue to open up debates in necessary ways. Exploring the missing book on wage labour, Lebowitz begins with the question of needs, and demonstrates that working class needs, or socially necessary labour time, is socially and historically contingent. This flexibility is what distinguishes us from other animals, in that needs shift according to what is available. As a commodity, labour power is unique in that the price of labour power (our wage) can determine our value. Yet, within capitalism, the only way that workers can satisfy their needs is through wage labour and consumption through the market. Although this is a relatively straightforward argument, it is also the foundation for one of the red threads throughout the book: that there is an integral but contradictory relation between these categories within the totality of capitalism. In simple terms, the worker is both labour power and consumer, and although necessary needs are the result of class struggle, ‘each new need becomes a new link in the golden chain that secures workers to capital’, citing Lebowitz. As such, within capitalism, the capacity for workers to realise their needs relies upon capital as mediator, which is where capital’s power comes from. Touching on, without fully entering, labour theory of value debates, what is suggested at here is an argument similar to Harry Cleaver on the value of labour for capital. When Lebowitz asks ‘Why, for example, does capital require a definite quantity of labour if the technical composition of capital is rising?’ his answer can be found in the way that new needs are produced and the reproduction of wage labour. For as long as capital remains mediator, what is reproduced – the value of labour for capital – is a relation of dependence. Rather than labour having a value as a definite input to production, the value of labour for capital is the power relation that is reproduced, and conversely according to Lebowitz: For the worker, the value of labour-power is both the means of satisfying needs normally realised and the barrier to satisfying more – that is, is simultaneously affirmation and denial. Thinking in more concrete terms, when wages decrease the quality of labour power may decrease, or when productivity rises the amount of labour needed to produce each product may decrease, but critically the wage relation is still reproduced. Again, gingerly opening a door to fierce feminist debates on unproductive/productive labour, without delving deep into their claims, Lebowitz concludes that ‘What we are presented with is productive labour for capital, labour which serves the need and goal of capital – valorisation,’ where this is made possible because of the reproduction of this relation of dependence. To re-centre class struggle as a key dynamic rather than after-effect of capitalist reproduction, Lebowitz approaches needs from multiple standpoints, and by doing so demonstrates how needs for labour and needs for capital from these different standpoints are incommensurate. This is reflected in his concept of a political economy of wage labour as the “other” to the political economy of capital. While framed as the counter to capital and reflecting the above tensions, the political economy of wage labour remains within the totality of capitalism. It is not equal in power—even if his graphics seem to suggest some equality – a constant annoyance in the reading group!—and serves a necessary function in the reproduction of the system as whole. What this concept allows us to do is approach the multiple circuits of production and reproduction from different standpoints (here touching on although not referencing feminist standpoint theory as much as Lukács’ approach to proletarian praxis), which centres rather than sidelines working class experience, logics, and needs. As such, unlike some autonomists or feminist interventions, Lebowitz makes a convincing argument that these other circuits are not autonomous from capital but rather operate within the totality and remain mediated by the demands of valorisation. However, this mediation does not mean that the political economy of wage labour is the same as the political economy of capital. The political economy of wage labour although essential to the reproduction of capitalism as a whole also exceeds it. Put differently, human experience is more than that which is visible on the terms of capital: concrete labour is not commensurate with abstract labour and it is this “extra” or messiness that Lebowitz, alongside many social reproduction theorists, are interested in. The worker is both wage labourer and non-wage labourer and this occurs through the same labouring body. There is—to borrow David McNally’s terms—a unity in difference within the totality, a totality understood here as a methodological premise that points to the way that the economic mediates and colours these other integral parts of the totality in complex and contradictory ways.