|

7/18/2022 Christianity Marxism and the Death of Reason in the Ancient World. By: Thomas RigginsRead NowCharles Freeman’s The Closing of the Western Mind is a great introduction to the origins of Christian thought. Today, with so many competing versions of Christianity, ranging from traditional Orthodox and Catholic views to liberal socially conscious Protestantism and right-wing evangelical fundamentalism, it is helpful to have a guide such as this which explains, supplemented by a Marxist outlook, how the original Christianity of the ancient world came about. Freeman will do a credible job of tracing this history from Roman times to the High Middle Ages. In his Introduction he tells us that he will be dealing with ‘’a significant turning point’’ in Western civilization. The point he has in mind is that time in the fourth and fifth centuries AD “when the tradition of rational thought established by the Greeks was stifled.” It would take the West a thousand years to recover. The Greek rational tradition was firmly established by the fifth century BC — its two greatest founders were Plato and his student Aristotle. Unfortunately, Freeman confuses modern day empiricism with rationality and misapprehends the significance of Plato, following in the footsteps of his master Socrates, in the establishment of the rational method in Greece. Plato’s thought was not “an alternative to rational thought” but one of the most extreme examples of it, subjecting all beliefs to the test of logical argument whenever possible. Be that as it may, Freeman thinks that the Greek rational tradition, today’s term would be “scientific,” was deliberately squashed by the Roman government from the time of Constantine with the aid of the official church. The wide-open intellectual environment of the Roman Empire, both religiously and philosophically, came to an end in the 4th century when the Emperor Constantine made Christianity the “official” state religion. The “official” version became the only legal version and thus was the “orthodox” version, “The imposition of orthodoxy,” Freeman writes, “Went hand in hand with the stifling of any form of independent reasoning.” Christianity was from the onset anti-rational. Freeman writes, “ It had been the Apostle Paul who declared war on the Greek rational tradition through his attacks on ‘the wisdom of the wise’ and ’the empty logic of the philosophers’ …” When Christianity became the official creed it closed down any contrary thinking thus dooming the West to a thousand yeas of backwardness. A good example of this mind closing is given by Freeman when he discusses the dispute between St. Ambrose and the traditional Roman senator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus. To my way thinking Symmachus had an open modern mind while Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan and teacher of S. Augustine, was a bigot. “In the late fourth century the seat of the Western Empire was in Milan and there were still many pagans (believers in the old traditional religion) who wished to be free to continue their form of religion. The Christian authorities were determined to repress all forms of religion save their own. One of the major symbols of the traditional religion was the Altar of Peace which adorned the Senate in Rome. The Christians had it removed in 383 AD. Symmachus and other senators petitioned the Emperor to have it restored. Ambrose (a major power behind the throne) was opposed and the petition failed. The mindsets of the two sides are clearly expressed in the following written exchange.” “Symmachus: ‘What does it matter by which wisdom each of us arrives at the truth? It is not possible that only one road leads to so sublime a mystery.’ Ambrose: ‘What you are ignorant of, we know from the word of God. And what you try to infer, we have established as truth from the very wisdom of God’” The Truth, however, should be able to triumph without the aid of the rack and the stake. Paul himself had no personal knowledge of Jesus in the flesh. Freeman asserts that the intolerance of the Christians (their rejection of logic and science) stems from Paul. What is worse, when, for political reasons the Roman state adopted the religion and forced it upon everyone, its motive was to control the minds of the population for the benefit of the empire. The actual teachings of Jesus were no more suited to the ends desired by the Romans than they are to the actions of US imperialism today and the fundamentalist and evangelicals who blindly support it in the name of patriotism. Paul, according to Freeman, distanced himself from the original 12 disciples (who distrusted his claims) and ended up, as we know, creating a theology that appealed to the Greco-Roman world and was rejected by the Jewish community from which Jesus came. In order to do this the real “historical” Jesus and his teachings (peace not war, forgiveness not vengeance, love and respect, not hatred and contempt— i.e., Martin Luther King, Jr, not Jerry Falwell nor Pat Robinson) had to be replaced with an unreal Christ beyond history. Thus, Freeman writes, “Paul makes a point of stressing that faith in Christ does not involve any kind of identification with Jesus in his life on earth but has validity only in his death and resurrection.” Thus the burden of actually having to follow the particular ethical path that Jesus the human trod is removed. [What is called “Christianity” today ought rather to be called “Paulism.”] Since the claims made for Jesus as the Christ are simply impossible to accept from the point of view of reason, reason is dumped and is replaced by “faith.” Freeman gives the following quote from the fourth century ascetic Anthony: “Faith arises from the disposition of the soul, those who are equipped with the faith have no need of verbal argument.” It is also interesting note, as Freeman does, that Anthony was claimed not to have learned ‘to read or write, the point being made by his biographer that academic achievement was not important for ‘a man of God’ and could even be despised.”… achieving a fill identification Freeman is incorrect, I think, in holding that the personal commitment Christians made to Christ (becoming “a single body with Christ through his death and then rising with him from the dead”) was “something new in antiquity.” This very belief was characteristic of the devotees of the Egyptian god Osiris whose worship in the cult of Isis and Osiris was widespread throughout the Roman Empire and whose popularity may explain why Christianity proved to be so popular to the Greco-Roman population. Mary idolatry, still rampant in some forms of Christianity, may have stemmed from this cult connection as well. Freeman points out that Isis was the patron goddess of mariners and her symbol was the rose. Mary replaced her as the patroness of sailors and her symbol was also the rose. He also writes, “representations of Isis with her baby son Horus on her knee seem to provide the iconic background for those of Mary and the baby Jesus.” The Greek rational tradition demanded that people think for themselves and take responsibility for their actions. Christianity introduced a different conception of moral responsibility. It introduced the idea of “don’t think, just follow orders.” Freeman quotes long extract from William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, in which a Jesuit explains the value of living the monastic life (every religion has something similar to this as well as some political groups on the left as well as the right). The Jesuit explains that if you obey the orders of your religious superior, no matter what they are, you can do no wrong! “The Superior may commit a fault in commanding you to do this or that, but you are certain that you commit no fault as long as you obey, because God will only ask you if you have duly performed what orders you received …. The moment what you did was done obediently, God wipes it out of your account….” Nice! Not even God respects the Geneva Conventions, why should the U.S. or anyone else? “Here the abdication to think for oneself is complete. The book clearly demonstrates that religion in the West has been used to deprecate and reject reason (unless the church can misuse it in its own interests). It also demonstrates that in the modern world ,the progressive part at any rate, represents a return to the Greek outlook. When Freeman, in reference to the teachings of the church, writes”The ancient Greek tradition that one should be free to speculate without fear and be encouraged to take individual moral responsibility for one’s views was rejected,” we can today assert that now in the 21st century, despite the tragic history of”real existing socialism” in the past century, no genuine Marxist committed to genuine people’s democracy would agree with the church on this matter. The most important internal reason for the collapse of the socialist block, I think, may have been the lack of real participatory democracy and citizen involvement. Traditional Christianity as well as fundamentalism may likewise now be facing this malaise which is also characteristic of American and other bourgeois “democracies, as well as some contemporary so-called Marxist groups which have learned nothing from the past. What Freeman writes about the Church can be extended to these other groups as well. “Intellectual self confidence and curiosity which lay at the heart of the Greek achievement, were recast as the dreaded sin of pride. Faith and obedience to the institutional authority of the church were more highly rated than the use of reasoned thought. The inevitable result was intellectual stagnation.” Reading Freeman’s well written and interesting book will give you a great background and a deep historical understanding as to how Christianity came to dominate the Western world for over a thousand years, and what that has cost in terms of intellectual degradation, and how, if the peoples of the West are to better their condition in this new century they must regain the intellectual confidence so characteristic of Greek civilization. I would maintain that the Marxist tradition, freed from the failed authoritarian models of the last century, is the best contemporary intellectual tool to achieve this end. But it is important to note that the Greeks were not the only people to have a rational outlook. Similar thinkers can be found in the “classical” periods of other cultures such as Ancient Egypt, China, India, and the Islamic culture of the Middle, to name but four, and the hope of a progressive future rests on a blending of the best progressive tendencies of all cultures. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives July 2022

0 Comments

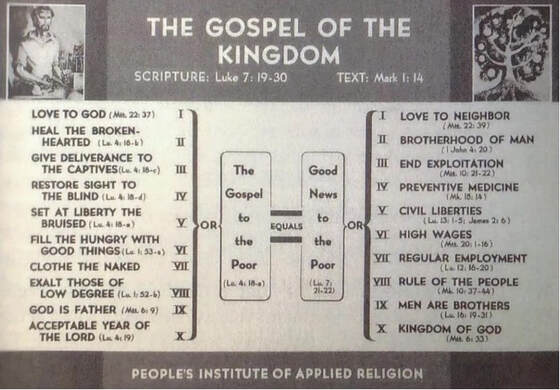

REINVENTING THE SACREDDenis Noble several years ago had a review ("For a Redefinition of God") of Stuart A. Kauffman's book REINVENTING THE SACRED: A NEW VIEW OF SCIENCE, REASON, AND RELIGION, in the 6-20-2008 issue of SCIENCE. Well, if God is going to get a new definition let's see what it is. Those of us who are skeptical as to God's “is-ness” do not want to be doubting the “is-ness” of what isn't the “is-ness” we think it is but some other “is-ness” that is entirely different. Maybe we can even learn about God's relation to Marxism. Kauffman, a theoretical biologist (there is an interesting Wikipedia article about him), argues that biology cannot be reduced to physics. This is anti-reductionist and Marxists could agree that there is a qualitative leap involved in the dialectics of emergent life. In biological evolution he says "ceaseless novelty" arises and "ceaseless creativity" takes place in nature. Is this a rehash of Henri Bergson's (1859-1941) creative evolution? Because of this ceaseless creativity Kauffman wants to recreate or reinvent the concept of the "sacred." Noble doesn't say why. This is what Kauffman says, "Seeking a new vision of the real world and our place in it has been a central aim of this book-- to find common ground between science and religion so that we might collectively reinvent the sacred." This will be a hopeless task since the new definition of God will be rejected by Christians, Muslims, and Jews, and most other people as well. No matter, as Noble quotes him as saying "we must use the God word, for my hope is to honorably steal its aura to authorize the sacredness of the creativity in nature." Why must we use the "God" word this way? Why can't we use the "God" word this way? "There is no God." That is using the word and without "stealing" its "aura. "For Kauffman the "creativity of nature" = "God" or as Spinoza said "Nature" = "God". How about this? History and the development of Marxism cannot be reduced to biology. Marxists are finding out, to their sorrow, the ceaseless novelty and creativity of history and Marxism. This makes Marxism, historical materialism, sacred due to its ceaseless creativity. I want to use the word "God", maybe even I must, so the "creativity of Marxism" = "God" and I will found the First Church of Marxism. As for Kauffman, Noble asks, "So, could his concept of God as nature's ceaseless creativity be convincing?" You can pray to it (just don't expect any answer). You can love it if you want to but it doesn't concern itself about you so don't wait up for any calls, and don't overlook that lump. "God," Noble says, "is not even given the power that the Deists recognize." And that's not much compared to what traditional religious people expect. Maybe a few Unitarians here and there, and some Buddhists, will buy into this idea. Noble concludes, "Bringing science and religion together globally in the way that Kauffman wishes is not going to be easy [do you think?] -- as other ecumenical movements have repeatedly found [including my First Church of Marxism]-- but it is necessary." Again with the "necessary." If something is necessary it will come about. I'm placing my money on the First Church of Marxism. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives February 2022 People's Institute of Applied Religion, founded by Claude C. Williams of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union “We therefore see that the Christianity of that time [referring to the book of Revelation] which was still unaware of itself, was as different as heaven from earth from the later dogmatically fixed universal religion of the Nicene Council; one cannot be recognized in the other. Here we have neither the dogma nor the morals of later Christianity but instead a feeling that one is struggling against the whole world and that the struggle will be a victorious one; an eagerness for the struggle and a certainty of victory which are totally lacking in Christians of today and which are to be found in our time only at the other pole of society, among the Socialists.’’ The views of the foundational figures of Marxism on the question of religion are not well known, except to depict Marxists as hostile toward religion. A few lines before his infamous depiction of religion as “the opium of the people,” Karl Marx, in an introduction to his Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, writes, “The struggle against religion is, therefore, indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion.” While Marxism undeniably arose from a critique of the atheistic “materialism” of Feuerbach, this distinction Marx makes about “the struggle against religion” is worth noting, and also seems discernable in later Marxist analyses of religion like Lenin’s 1905 essay “Socialism and Religion.” In Lenin’s time, as Karl Polanyi noted, the Czarist (Caesarist) feudal power structure faced little opposition from the ranks of the Orthodox Church. (“The Essence of Fascism”) After the famous “opium of the people” sentence, Marx continues with lines that are less quoted: “The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.” Similarly, the views of the foundational figures of Christianity on the question of class struggle are not well known, except those scriptures which can be used to pacify the masses. Rarely is the scripture from the Epistle of James quoted from American pulpits, “Is it not the rich who oppress you?” (James 2:6) In Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy, Engels wrote of early Christianity, “What it originally looked like has to be first laboriously discovered again, since its official form, as it has been handed down to us, is merely that in which it became a state religion, to which purpose it was adapted at the council of Nicaea.” In the Epistle of James, the unknown church father warns against showing partiality to those who “wear gold rings,” which in the Roman imperial context certainly included emperors like Constantine. By giving the Roman emperor a seat at the council of Nicaea, the church fathers of the fourth century may have not only been ignoring the warning of James, but may also have been betraying the very counter-imperial theology which proclaimed Jesus of Nazareth the “Son of God,” an epithet of the Roman emperor. If the Roman emperor was the antichrist of John’s Revelation, surely the word of Our Lord would apply, “No one can serve two masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth.” (Matthew 6) Church fathers who came just after the generation of Nicaea like Ambrose of Milan and Basil the Great may represent some of the class politics that was considered “orthodox” before the full integration of the church into the Roman Empire. In his sermon “On Naboth,” Saint Ambrose claims that greedy Ahabs and murdered Naboths are born every day, referring to the story in I Kings of a monarch who kills a poor man in order to take his property. “How far, O rich, do you extend your mad greed? ‘Shall you alone dwell upon the earth’ (Isa. 5:8). Why do you cast out the companion whom nature has given you and claim for yourself nature’s possession? The earth was established in common for all, rich and poor. Why do you alone, O rich, demand special treatment?” (Ambrose “On Naboth”) Basil the Great says, “The beasts become fertile when they are young, but quickly cease to be so. But capital produces interest from the very beginning, and thus in turn multiplies into infinity. All that grows ceases to do so when it reaches normal size. But the money of the greedy never stops growing.” (Basil, Homily on Psalm 14) The whole of Christian history is worth analysing from the perspectives of class, patriarchy, disability, ecology, and colonialism. One period of Christian history was analysed by Frederick Engels in his 1850 book The Peasant War in Germany. A rival Reformer to Martin Luther, the German preacher Thomas Müntzer wrote in an 1524 anti-Luther pamphlet titled A Highly Provoked Defense, “Whoever wants to have a clear judgement must not love insurrection, but equally, he must not oppose a justified rebellion.” (Sermon to the Princes) He continues, “The people will be free. And God alone will be lord over them.” (p. 92) A year later, Müntzer was tortured and executed as a leader of the German Peasant Rebellion. While Luther worked to integrate his Reformation into the feudal power structure of 16th century Germany, Müntzer railed against the land-owning nobility who dominated Early Modern Europe. Instead of assimilating to the values of the kingdoms of earth, Müntzer pointed to the example of the early church in Acts 2 and 4: omnia sunt communia — “all things held in common.” “The stinking puddle from which usury, thievery, and robbery arises is our lords and princes. They make all creatures their property—the fish in the water, the bird in the air, the plant in the earth must all be theirs. Then they proclaim God's commandments among the poor and say, ‘You shall not steal.’” (A Highly Provoked Defense) Engels describes Müntzer’s gospel in glowing terms: “By the kingdom of God, Muenzer understood nothing else than a state of society without class differences, without private property, and without superimposed state powers opposed to the members of society.” For many, Müntzer falls into the category of history reserved for so-called “idealists” (not the Hegelian kind per se)—seemingly crazed martyrs like the 19th century abolitionist John Brown. A similar lone radical figure is present in both the synoptic gospel narratives of Jesus’ life and the Antiquities of Josephus. “A voice crying out in the wilderness Josephus identifies him as “John, who was called the Baptist.” His account of John’s death reads: “Now many people came in crowds to him, for they were greatly moved by his words. Herod, who feared that the great influence John had over the masses might put them into his power and enable him to raise a rebellion (for they seemed ready to do anything he should advise), thought it best to put him to death. In this way, he might prevent any mischief John might cause, and not bring himself into difficulties by sparing a man who might make him repent of it when it would be too late.” (Jewish Antiquities 18.118) This account of the reasoning for Herod’s execution of John the Baptist is different from that which is reported in the gospel narratives, but has strong resonances with other passages in Matthew and Luke. A very obscure saying like “From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven has suffered violence, and the violent take it by force,” seems to reflect the kind of violent revolutionary conflict that indeed took place in Roman-occupied Palestine. Many rebellions were even led by men who claimed to be the Messiah. There is obvious evidence to support the notion that a potentially historical Jesus of Nazareth chose the path of nonviolent resistance to Roman oppression rather than the path of the Zealots. However, Jesus’ alleged proximity to the figure of John the Baptist may be an indication of the revolutionary nature of the original Jesus movements, or at least the attitudes of the ruling classes towards the movement while it was on the rise. (Horsley’s Jesus and Empire is an accessible primer on first-century Palestinian resistance to Roman rule.) John the Baptist, who calls the elite factions of Palestine a “brood of vipers,” apparently requested confirmation that Jesus was the “one who is to come” while he was incarcerated in Herod’s prison. As economist Michael Douglas and theologian Sharon Ringe have pointed out, Luke and Matthew record Jesus answering John’s messengers: “The poor have good news brought to them.” While Jesus and John’s movements may have been separate, this message apparently united them. The gospels of Luke and Matthew also corroborate Josephus’s observation that the rulers of Palestine “feared the people.” In Luke, when Jesus asks the religious establishment if John’s baptism was of divine or human authority, they consult amongst themselves, “If we say, ‘From heaven,’ he will say, ‘Why did you not believe him?’ But if we say, ‘Of human origin,’ all the people will stone us; for they are convinced that John was a prophet.” Later in the same chapter, Luke says the chief priests and scribes “wanted to lay hands on him at that very hour, but they feared the people.” (Luke 20:19) Perhaps that is why in Luke 22, the religious leaders enlist the “temple police” to help them apprehend Christ. (22:52) “For I tell you, this scripture must be fulfilled in me, ‘And he was counted among the lawless.’” (22:37) Indeed, the cross was typically used to execute slaves like Spartacus, rebels, and bandits. In 1940, radical folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote a song titled “Jesus Christ,” which identifies “the bankers and the preachers,” “the landlord, cops, and soldiers” as the ones who “laid Jesus Christ in his grave.” Guthrie died a poor man in 1967, the same year as his contemporary Langston Hughes, whose poem “Bible Belt” anticipates the theology of the great James Cone: It would be too bad if Jesus The Nazarene once proclaimed the gospel in a field: “Blessed are the poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” Let that kingdom come, through our wills and our actions. Through God’s will and spirit. On earth as in heaven. Just four verses after Christ’s final sermon in the book of Matthew (‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’), a woman comes to anoint Jesus at the house of a leper. (Matthew 26) When his disciples try to condemn the woman’s use of fine perfume as wasteful, Jesus responds in what I imagine to be the sarcastic tone he used toward the Pharisees and Herodians who tried to catch him with a question about paying taxes to Caesar. As Reverend Dr. Liz Theoharis shows in her book Always With Us?, the phrase, “You will always have the poor with you,” is a reference to the law of Jubilee in Deuteronomy, a book Matthew’s gospel draws heavily from. “Every seventh year you shall grant a remission of debts. [...] There will be no one in need among you, if only you will obey the Lord your God by observing this entire commandment.” (Deuteronomy 15) Let the law be fulfilled in our hearing and doing. Luke’s gospel, cited repeatedly above, seems to present a more noticeably class-conscious version of the already egalitarian good news presented in Matthew and Mark. As Dennis MacDonald has noted, the Gospel of John, known as the latest gospel, seems to take issue with some of Luke’s narrative—notably in his transformation of Lazarus the parabolic homeless man into a friend of Jesus who is raised from the dead. Both Lazarus stories deal with resurrection: in Luke, a rich man who ignored the begging Lazarus at his gate, calls out to Abraham from the fires of Hades, asking him to send Lazarus back to the land of the living to warn his family of the coming judgement on the rich. “Remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in agony,” Abraham says. “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.” (Luke 16) Revolutionary and first president of Burkina Faso Thomas Sankara said, “No altar, no belief, no holy book, neither the Qur’an nor the Bible nor the others, have ever been able to reconcile the rich and the poor, the exploiter and the exploited. And if Jesus himself had to take the whip to chase them from his temple, it is indeed because that is the only language they hear.” The exploitation of the poor by the rich is indeed condemned by our holy books, from the prophets Micah, Amos, Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Habakkuk, through the gospels and epistles. After rejecting the rich young ruler, Christ says with God all things are possible. But a camel does not pass through the eye of a needle without a miracle. (Mark 10) If the light within you is darkness, how great is that darkness! Such blindness befalls a world which bows before the altar of Mammon. The imperialist “wisdom of the rulers of this age” is foolishness to God. The economy was made for humanity, not humanity for the economy. Historian Christopher Wilson wrote recently about Juneteenth for the Zinn Education Project, “As with an incarcerated prisoner who may be told she is free, until the prison bars are unlocked that word only results in theoretical freedom.” Freedom, abolition, and justice are words which must become flesh. The epistle of James speaks again, “Be doers of the word, and not merely hearers of the word who deceive themselves.” Mary proclaims the good news of our Deliverer: He lifts up the lowly and fills the hungry with good things. For those who cause the least of these to stumble, Christ prophesies the millstone. “God wept; but that mattered little to an unbelieving age; what mattered most was that the world wept and still is weeping and blind with tears and blood. For there began to rise in America in 1876 a new capitalism and a new enslavement of labor. Home labor in cultured lands, appeased and misled by a ballot whose power the dictatorship of vast capital strictly curtailed, was bribed by high wage and political office to unite in an exploitation of white, yellow, brown and black labor, in lesser lands and “breeds without the law.” Especially workers of the New World, folks who were American and for whom America was, became ashamed of their destiny. Sons of ditch-diggers aspired to be spawn of bastard kings and thieving aristocrats rather than of rough-handed children of dirt and toil. The immense profit from this new exploitation and world-wide commerce enabled a guild of millionaires to engage the greatest engineers, the wisest men of science, as well as pay high wage to the more intelligent labor and at the same time to have left enough surplus to make more thorough the dictatorship of capital over the state and over the popular vote, not only in Europe and America but in Asia and Africa. “Decolonization never goes unnoticed, for it focuses on and fundamentally alters being, and transforms the spectator crushed to a nonessential state into a privileged actor, captured in a virtually grandiose fashion by the spotlight of History. It infuses a new rhythm, specific to a new generation of men, with a new language and a new humanity. Decolonization is truly the creation of new men. But such a creation cannot be attributed to a supernatural power: The ‘thing’ colonized becomes a man through the very process of liberation. Decolonization, therefore, implies the urgent need to thoroughly challenge the colonial situation. Its definition can, if we want to describe it accurately, be summed up in the well-known words: AuthorZachary White Kairos fellow, Union Theological Seminar Archives September 2021 5/25/2021 Book Review: Slavoj Zizek and Perverse Christianity (2003). Reviewed By: Thomas RigginsRead NowIn his book, “The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity” the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek puts forth the view that Marxists can no longer make a frontal attack on the institutions of imperialism, thus a feint under the cover of Christianity is necessary. Zizek calls himself "a materialist through and through" and believes that Christianity has a "subversive kernel" which can only be demonstrated by a materialist analysis. But he also holds that the relationship is so intimate that "to become a true dialectical materialist, one should go through the Christian experience." Zizek maintains that for "intelligent Marxists" the most interesting questions are not those about change and development – but about permanence and stability. Why has Christianity persevered from ancient times? We "find it in feudalism, capitalism, socialism..." etc. The clue is to be found in the writings of the Catholic writer G.K. Chesterton who wrote that despite the rigid ethical and moral demands of the Church and its priests, an inhuman "outer ring" it actually protected the masses of people where one would find "the old human life dancing like children and drinking wine like men; for Christianity is the only frame for pagan freedom." Pagan freedom is another term for joy in living. This may explain the persistence of Christianity, but why must Marxists have the Christian experience? This is too unrealistic a claim. Do Asian Marxists from non-Christian cultural backgrounds have to convert to Christianity in order to have the "Christian experience" before fully understanding dialectical materialism? Other religions have also been persistent. Hinduism, for example, is older than Christianity, as is Buddhism, and has adapted to the modern world. Zizek does discuss some of these other religions but is on shaky ground. He seems to think, for instance, that Bodhisattva is the name of a person rather than being a title used to describe Mahayana Buddhist “deities”. Zizek’s "materialism" or at least his "Marxism" is also all mixed up with categories borrowed from Lacanian psychoanalysis. And here is a digression based on W.L.Reese’s work Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought: Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) was a French psychoanalyst who thought the unconscious Id expresses itself in language because it is structured like a language. The Ego should recognize the depth and plurality of meanings of the Id. This is hard to do as the Ego = our personal identity, our conscious self which is only composed of the info allowed through by the Censor. Lacan wants to subvert not strengthen the Ego. The Ego is a mess due to problems in infancy and it is this screwed up infantile Ego, surviving into adulthood, that must be subverted by the usual psychoanalytic methods. Using this Lacanian world view plus "Marxism," Zizek decides that by using a "perverse" version of Christianity leftists can smuggle in, as it were, progressive ideas and put them into play in our society. Having concluded that Marxism cannot get a hearing in our culture this is really the only way that we can advance the revolutionary cause. Marxists in Christian clothing. No doubt that because Christianity originated among oppressed national minorities and slaves there are many features of progressive social justice that can be deduced from it. The battle against the Christian right could be more easily waged by showing that its political and social formulations are contrary to Christian teachings and the logic of Christianity. In this respect Zizek has a point. But it is not necessary for Marxists to go through a Christian moment themselves. By the way, the "puppet" in the book’s title is Christian theology – we (the “dwarf”) will use theology to forward our secular ends – the dwarf will use the puppet. People interested in philosophy and religion may want to read this book. I have only scratched the surface in this brief article. At the end, Zizek says the point of his book is to show that Christianity at its core reveals the secret of the passion of the Christ (one that Mel Gibson missed). When Christ dies after asking his Heavenly Father why He has abandoned him, the historical secret is that there is no Heavenly Father. So is “Christ” just hallucinating? There is no "Other" to judge us. We are responsible. This is the perverse core of Christianity and Zizek takes us on an interesting tour of the history of Western thought to get there. You might not like all of the stops along the way, or even the final destination, but you may well enjoy the trip. Nevertheless, I don’t think we will ever start preaching Marxism-Leninism-Jesus Christ Thought. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives May 2021 In order to be viable, a left-wing secular humanism must recognize the complicated dynamics associated with organized religion and its influence on political parties and social movements. Crucial questions emerge that must be addressed. How much should religion influence the development of new parties? What should a left political party’s stance toward religion be, especially in regards to individual members? How can we advocate for atheism or materialism, in any form, while allying with those who are ideologically different? One of the most insightful, and definitely controversial, political theorists who reckoned with these questions was Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. A deeply influential figure of 20th century world history, Lenin led the intellectual and political transformation of rural, peasant eastern Europe into the first sustained socialist government of the world, the Soviet Union. His revolutionary Marxism influenced movements around the globe, from Cuba and China to the Pan-African socialists of the 1960s and 1970s. His books Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism and State and Revolution are still required reading for those interested in radical, left politics generally and Marxism in particular.* In this analysis, we will delve into two of Lenin’s essays: “Socialism and Religion”, published in the Bolshevik newspaper Novaya Zhizn (New Life) on December 3, 1905, and “On the Significance of Militant Materialism,” published in the philosophical journal Pod Znamenem Marksizma (Under the Banner of Marxism) on March 12, 1922. Each shows both the consistency of Lenin’s thought on the religious question as well as his evolution as a political theorist before the revolution and after. In these short but incisive pieces, Lenin defended traditional secularist values, such as the separation of church and state, liberty of conscience, and free religious association, while also calling for the political separation of religion from political parties and strategically advocating for the atheist/materialist worldview. While it would be too much to say that Lenin was a “humanist” in the general sense of the term, he was nevertheless a secularist whose insights on religion provide left humanists with clear, tactical advice on the interrelationship between faith and politics in the public sphere. As a historical materialist, Lenin outlined in “Socialism and Religion” how capitalism as a mode of production creates the economic and cultural conditions of the society it constructs. “Present-day society is wholly based on the exploitation of the vast masses of the working class by a tiny minority of the population, the class of the landowners and that of the capitalists,” he wrote. In effect, the capitalist society “is a slave society, since the ‘free’ workers, who all their life work for the capitalists, are ‘entitled’ only to such means of subsistence as are essential for the maintenance of slaves who produce profit, for the safeguarding and perpetuation of capitalist slavery.” These conditions create what Marx called “alienation,” or a separation from ourselves, our work, and even life itself. Lenin echoed this notion when he declared, “the economic oppression of the workers inevitably calls forth and engenders every kind of political oppression and social humiliation, the coarsening and darkening of the spiritual and moral life of the masses.” This “coarsening and darkening” manifests itself most starkly in the form of religion, which Lenin further elucidated. “Religion is one of the forms of spiritual oppression which everywhere weighs down heavily upon the masses of the people, over burdened by their perpetual work for others, by want and isolation,” he penned. As the conditions of life continually degrade under the forces of capitalism, a reversion to spiritual concerns courses through the working class. By contrast, leaders of such a society, organized around the principle of exploitation, use religion as a tool for laundering their guilt. Thus, religion becomes a palliative for not only those at the bottom but for those at the top. Recalling Marx’s famous line from A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Lenin said, “Religion is opium for the people. Religion is a sort of spiritual booze, in which the slaves of capital drown their human image, their demand for a life more or less worthy of man.” Lenin countered this view by stressing the importance of class consciousness, whereby the working class acknowledges its lot in life, begins to actively critique capitalist society, and strives to change it. The “modern class-conscious worker,” Lenin expounded, “reared by large-scale factory industry and enlightened by urban life, contemptuously casts aside religious prejudices, leaves heaven to the priests and bourgeois bigots, and tries to win a better life for himself here on earth.” Lenin again echoed Marx and Engels’ foundational work, The German Ideology, wherein they wrote, “In direct contrast to German philosophy which descends from heaven to earth, here we ascend from earth to heaven.” As such, the “modern class-conscious worker” discovers the indispensable connection between socialism and science, as it “frees the workers from their belief in life after death by welding them together to fight in the present for a better life on earth.” Lenin’s socialism was one rooted in materialism, historical analysis, class consciousness, and scientific discovery. With this understanding in mind, what is a socialist’s proper attitude towards religion? Lenin broke it down into two major components: the private (relating to the individual) and the political (relating to the party). He summed up this distinction well in a brief passage: “We demand that religion be held a private affair so far as the state is concerned. But by no means can we consider religion a private affair so far as our party is concerned.” In relation to the private, Lenin struck a chord reminiscent of the eighteenth century Enlightenment thinkers Voltaire and John Locke, demonstrating that Marxism (and Leninism) is not a rejection of the Enlightenment, but a manifestation of its better aspects. Lenin believed that “everyone must be absolutely free to profess any religion he pleases, or religion whatever, i.e., to be an atheist, which every socialist is, as a rule.” Lenin advocated for liberty of conscience, wherein every person can believe or not believe without the fear of government intrusion. Additionally, Lenin declared that “complete separation of Church and State is what the socialist proletariat demands of the modern state and the modern church.” Religions, in effect, should be “absolutely free associations of like-minded citizens, associations independent of the state.” The lesson here for us in the 21st century is that a viable socialist project is one that defends individual rights while fighting for the common cause of the working class, i.e. emancipation from the capitalist mode of production. Where Lenin stepped beyond the eighteenth century conception of religious liberty is his view that socialists are, “as a rule,” atheists. While many socialists in history have been atheists of one stripe or another (Marx, Mikhail Bakunin, Emma Goldman), there is a Christian socialist tradition that he dismisses. It’s not out of malice, but rather ideology. Marxism, traditionally, has largely been an atheistic worldview. Marx himself rejected religion on materialist grounds, arguing that if societies developed beyond scarcity, religious feelings would dissipate and organized religion itself would wither. Lenin saw his conception of atheism as an extension of Marx’s, hence his pronouncement that socialists are generally atheists. It should be emphasized here that, like science, there is no “royal road” to socialism. Socialists come from many different backgrounds and belief systems, so it is important for us as left humanists to understand and embrace these differences. Lenin, grasping the importance of movement building and solidarity, grasped the value in supporting religious movements whose interests align with the socialists. In 1905, within the tumult of an emerging revolution, the “police-ridden feudal autocracy” of Russia forced Russian Orthodox members to spy on citizens. They protested the move and Lenin enthusiastically supported their actions. “We socialists must lend this movement our support,” he said, “carrying the demands of honest and sincere members of the clergy to their conclusions, making them stick to their words about freedom, demanding that they should resolutely break all ties between religion and the police.” Like Lenin in 1905, the socialists of today must support religious groups who yearn for their freedoms in an open society, especially when it involves fighting the police state. In contrast with the private view of religion, Lenin maintained that the role of the party is to support not only the separation of church and state, but use its influence to rid society of malevolent religious beliefs and practices. Since a “party is an association of class-conscious, advanced fighters for the emancipation of the working class,” he writes, “such an association cannot and must not be indifferent to lack of class-consciousness, ignorance, or obscurantism in the shape of religious beliefs.” The party acts as an institution of critical thinking, wherein members use their position to educate others on the harmful absurdities of superstitious thinking, what Lenin calls the “struggle against every religious bamboozling of the workers.” It also acts as a disseminator of knowledge. Since a party’s outlook should be materialist, according to Lenin, its party programme “necessarily includes the propaganda of atheism,” namely “the publication of the appropriate scientific literature.” Taking a cue from Engels, Lenin advocates for a party “to translate and disseminate the literature of the eighteenth-century French Enlighteners and atheists.” (He returns to this idea in “On the Significance of Militant Materialism.”) However, Lenin acknowledged the limits of propaganda with regards to the religious question. While education is vital, the material conditions of a society must also change in order for secularism to thrive, precisely because those conditions created the religious impulse in the first place. “It would be bourgeois narrow-mindedness,” Lenin wrote, “to forget that the yoke of religion that weighs upon mankind is merely a product and reflection of the economic yoke within society.” This passage reinforces Lenin’s view that religion is a product of material forces, and as such, will only wither away when those material forces are restructured by a united working class for the benefit of all. Lenin, who valued working class solidarity, understood dividing the proletariat along religious lines for party purity as impractical and disastrous. Admitting to a party some of the working class whose religious beliefs coincide with a commitment to science and class struggle was a necessity. Additionally, he stressed that the religious question should only be addressed when appropriate, specifically when it relates to material forces and class struggle. He deemed it foolish to split the burgeoning proletariat “on account of third-rate opinions or senseless ideas, rapidly losing all political importance, rapidly being swept out as rubbish by the very course of economic development” and that only in unity “the proletariat will wage a broad and open struggle for the elimination of economic slavery, the true source of the religious humbugging of mankind.” The secular humanist left, therefore, should be direct about its lack of religious beliefs and commitment to a naturalist, materialist view of the world. Yet, we should not use our convictions as a cudgel with which to harm those of religious beliefs, nor do they preclude us from working with religious organizations on raising class consciousness and advocating for a post-capitalist world. The 1917 “October Revolution'', which overthrew the bourgeois government instituted after the fall of the Tsars, brought Lenin to the center of political power. “On the Significance of Militant Materialism,” written five years after the revolution, continued Lenin’s exploration of religion amidst the Bolshevik party’s attempt to build “actually existing socialism.” Pod Znamenem Marksizma, or Under the Banner of Marxism, was a journal established in 1922 with the goal of “popularizing militant materialism and atheism,” as mentioned in the notes of Lenin’s selected works. Lenin’s essay was a rejoinder to one written by fellow revolutionary Leon Trotsky, published in the journal’s inaugural issue. “In such a deeply fractured, critical, and unstable era as ours,” Trotsky wrote, “education of the proletarian vanguard requires serious and reliable theoretical foundations.” Those theoretical foundations must be materialist, “so that the greatest events, the powerful tides, rapidly changing tasks, and methods of the party and state do not disorganize his consciousness and do not break down his will before the threshold of his independent responsible work.” Like Lenin, Trotsky insisted that education, of both Marxist and non-Marxist texts, led to the development of a flourishing, socialist society. Lenin began his article praising Trotsky’s remarks and reiterating the importance of a broad education in materialism. Communists and non-Communists, who are nevertheless committed to materialism, should align to advance their educational goals. This partnership represented a forward move in revolutionary actions, specifically in relation to Lenin’s concept of the “vanguard.” As Paul D’Amato wrote in Socialist Worker, “Lenin's concept of the ‘vanguard’ party is the simple idea that working-class militants and other activists who have come to the conclusion that the whole system must be dismantled must come together into a single organization in order to centralize and coordinate their efforts against the system.” However, the vanguard would itself be democratic and open to outside influences. Lenin reaffirmed this position when discussing alliances with non-Communists: A vanguard performs its task as vanguard when it is able to avoid being isolated from the mass of the people it leads and is able really to lead the whole mass forward. Without an alliance with non-Communists in the most diverse spheres of activity there can be no question of any successful communist construction. This is especially true on the issue of education. Lenin defended the rich history of materialist thinking in Russia and declared, “it is our absolute duty to enlist all adherents of consistent and militant materialism in the joint work of combating philosophical reaction and the philosophical prejudices of so-called educated society.” The lesson for us today is that secular humanists must align and support those who defend the materialist view of reality and history, to fight against the forces of idealism and ahistoricism, what Lenin (quoting Joseph Dietzgen) named the “graduated flunkeys of clericalism.” Another indispensable element of Lenin’s framework regarding materialism and education is “militancy,” which refers to “the sense of unflinchingly exposing and indicting all modern ‘graduated flunkeys of clericalism’, irrespective of whether they act as representatives of official science or as freelances calling themselves ‘democratic Left or ideologically socialist’ publicists.” Publications dedicated to materialism should not pull punches when it comes to critiquing ideas, those who propagate them, and their relationship to society. In that vein, militancy has two components: militant materialism and militant atheism. Militant materialism emphasizes the “connection between the class interests and the class position of the bourgeoisie and its support of all forms of religion on the one hand, and the ideological content of the fashionable trends on the other.” In other words, it grounds philosophical, literary, and scientific currents in material conditions and class structures. Militant atheism is just what it sounds like: clearly and unapologetically defending a non-theistic worldview. Lenin’s militancy might sound like something akin to the “New Atheism” of intellectuals like Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, and Richard Dawkins, but it is nothing of the sort. Harris, Hitchens, Dawkins, and many others of this camp critique religion almost exclusively on ideological grounds, ripping it from the contexts of history and political economy. It’s also expressed in a way that resorts to racism, xenophobia, and imperialism, things Lenin stood strongly against. Lenin’s militant atheism, on the other hand, arises from Marxism and probes the material forces that developed and inculcated religions. He also doesn’t use atheism as a pretext to defend bourgeois political projects, like imperialism or colonialism. It’s a left atheism, rooted in the materialist process and completely different from the ahistorical, anti-materialist bromides of the New Atheists. Alas, atheism is challenging for many to adopt, especially in the working class. This is why broad literacy in the materialist thinkers of the past holds such a large place in Lenin’s conception of revolutionary politics. Like in “Socialism and Religion,” Lenin advocated in “Militant Materialism” for the translation and dissemination of “the militant atheist literature of the late eighteenth century for mass distribution among the people.” As these writers were clearly not Marxists, Lenin acknowledges their limitations and advocates for annotated editions that contextualize these thinkers; doing so provides the public with “most varied atheist propaganda material...from the most diverse spheres of life” Thus, militant materialism is only developed via Marxist and non-Marxist thought working in tandem to educate modern society, providing readers with incisive critiques of religion. It would be to the detriment of the working class and its development to ignore these valuable readings. In contrast to the classic writings of atheism, Lenin decried the “modern scientific critics of religion” who “almost invariably ‘supplement’ their own refutations of religious superstitions with arguments which immediately expose them as ideological slaves to the bourgeoisie.” He provided two examples demonstrating this trend. The first is Professor Robert Y. Wipper, who, in his book, The Origin of Christianity, relayed the relevant science refuting archaic superstitions while refusing to take a position on said mysticism. He claimed to be “above both ‘extremes— the idealist and the materialist.” Lenin, cutting through the cant, called this waffling on religious matters “toadying to the ruling bourgeoisie, which all over the world devotes to the support of religion hundreds of millions of rubles from the profits squeezed out of the working people.” Marxists should be consummate materialists, Lenin asserted, and ideological fence-sitting of this kind was not to be tolerated. The second example cited by Lenin comes from German intellectual Arthur Drews and his book, The Christ Myth.** Drews argued in this work that Jesus Christ, as a historical figure, never existed, yet advocated for a “renovated, purified and more subtle religion” that would withstand “the daily growing naturalist torrent.” Like with Wipper, Lenin lacked patience with this viewpoint, as it only reinforced traditional religious structures and existing class dynamics. “Here we have an outspoken and deliberate reactionary,” Lenin quipped, “who is openly helping the exploiters to replace the old, decayed religious superstitions by new, more odious and vile superstitions.” Nevertheless, Lenin encouraged translating and disseminating works from Drews and others like him, as they were vital to the struggle against even more reactionary forces of religious belief. On a practical level, Lenin still actively encouraged Marxists to ally with “the progressive section of the bourgeoisie” in the “struggle against the predominating religious obscurantists.” He sees Drews’ mistakes as akin to those of the eighteenth-century writers, and to reject the value of Drews’ work would be denying the worth of the enlightenment thinkers. This is an interesting point to linger on. Lenin, the ur-example of militant materialism and Marxism, still saw the work of non-Marxists as vital to the struggle for better conditions, both intellectually and materially. Despite flaws, their views still provided immense worth to the movement. It is the role of Marxists to expose these errors while also championing their better ideas. Lenin presented a crucial lesson for left humanists: despite our own misgivings about some religious ideas, we shouldn’t reject collaborating with religionists who share our goals. Whether we’re encouraging people to leave religious fundamentalism or uniting on a common cause like universal healthcare, humanists and religionists can cooperate for the improvement of society. Lenin’s mixture of ideological orthodoxy and practical policy is a superb example of the dialectical thinking vital to a conception of left-wing secular humanism. Alongside considerations of non-Marxist philosophy or history informing the working class on materialism, Lenin maintained that the advancements of modern science and its practitioners should also play a role. Militant materialism, in his estimation, should forge an “alliance with those modern natural scientists who incline towards materialism and are not afraid to defend and preach it as against the modish philosophical wanderings into idealism and scepticism which are prevalent in so-called educated society.” Additionally, modern scientists should be educated in dialectical materialism, the philosophical framework developed by Marx and Engels (following Hegel) that emphasizes the complex interactions of materials forces that create our real, lived experience. Thus, scientists engaged in research should review the dialectical writings of Hegel, Marx, and Engels and apply them systematically, which, as Lenin pointed out, would inoculate them against “intellectual admirers of bourgeois fashion” who “‘stumble’ into reaction.” Much like Marxist philosopher of science Roy Bhaskar argued decades later, Lenin recoginzed the integrative power of dialectical philosophy as indispensable, since “natural science is progressing so fast and is undergoing such a profound revolutionary upheaval in all spheres that it cannot possibly dispense with philosophical deductions.” V. I. Lenin’s “militant materialism”, while contentious, provides essential lessons to left secular humanists on the variegated interaction between religion and socialism. As a theorist of the political party, Lenin advocated for the separation of church and state, freedom of conscience, and political participation with religionists, while defending atheism and materialism as core value propositions of the Marxist left. In regards to mass education, Lenin encouraged the dissemination of materialist and atheist writers, Marxist and non-Marxist, as a means of growing the working class’s conception of secularism. In true dialectical fashion, Lenin’s ideas are a study in contrasts. He’s an ideologue dedicated to a steadfast conception of materialism and a pragmatist when it comes to movement building and consciousness raising. With this, he’s following Marx and Engels, who advocated the same thing in the Communist Manifesto. While not everything he champions might translate to our struggles today, Lenin’s secularism, materialism, and atheism nevertheless leaves a clear and influential example for us to learn from. Notes * It is not the place of this essay to litigate the horrors that emerged from the Stalinist period. For a Marxist analysis of Lenin and the period after his death, see Rob Sewell’s excellent essay, “In Defense of Lenin” (2014). ** Mythicism, or the belief that Jesus Christ was not a historical person, is a hotly-debated subject within the broader secular community, though not within traditional historical scholarship. The fact that Lenin may have entertained this idea is intriguing, to say the least. To learn more about mythicism and its issues, see Bart Erhman’s book, Did Jesus Exist? (2012). AuthorJustin Clark is a Marxist public historian and activist. He holds a B.S. in History/Political Science from Indiana University Kokomo and a M.A. in Public History from Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. His graduate research focused on orator Robert Ingersoll and his contributions to Midwestern freethought. You can contact him at [email protected] or follow him on Instagram at @justinclarkph. This article was first published by Justin Clark's Blog. Archives May 2021 Historically, Marxism has been perceived to be inexorably hostile to religion and especially to Christianity (since Marxism grew up in the Christian West). Nowadays most non-Marxists think Marxism is hostile to all religions and looks down on those who have religious beliefs. There are others today who think Marxism has become more mellow and is either neutral about religion or even somewhat encouraging in its attitudes towards some religious opinions. I hope to show that a contemporary Marxist position will incorporate some of both these perceptions. The basic Marxist position was first enunciated by Marx as long ago as 1843 in his introduction to a "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Law." This work contains the famous "opium of the people" remark. More pithy than Lenin's "Religion is a sort of spiritual booze", which I am sure it inspired. What did Marx mean by calling religion an opiate? Being a materialist, Marx of course holds to the view that religion is ultimately man made and not something supermaterial or supernatural in origin. "Man makes religion," he says. Man, or better, humanity is not, according to Marx, some abstract entity, as he says, "encamped outside the world." In the world of the early nineteenth century the masses of people lived in horrendous societal conditions of poverty and alienation and lived lives of hopeless misery. This was also true of Lenin's time, as well as of our own for billions of people in the underdeveloped world as well as millions in the so called advanced countries. The social conditions are reflected in the human brain ("consciousness") and humans living in such conditions construct their lives according to these reflections (ideas). These social conditions and ideas give rise to forms of culture, political states, and ideas about the nature of reality and the meaning of it. Marx says, "Religion is the general theory of that world... its universal source of consolation and justification." The world we live in is one of exploitation and the human spirit or "essence" appears in a distorted and estranged form. This is all reflected in religion as if it (the human spirit or essence) had an independent existence rather than being our own self-creation out of our interactions with the terrible societal conditions in which we find ourselves. In order to improve our conditions we must struggle against the imperfect social world and the ideas we have in our heads that that world has placed there and which reinforce its hold on us. This leads Marx to say. "The struggle against religion is therefore indirectly a fight against the world of which religion is the spiritual aroma." This is the background to Marx's view of religion as an opiate. The complete quote is: "Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of spiritless conditions. It is the opium of the people." Lenin remarks that this dictum "is the corner-stone of the whole Marxist outlook on religion." (CW:15:402) Marx has more to say than this, however. It is possible to misinterpret Marx's intentions by not going beyond this dictum. Let's see what else he has to say. Remember that Marx said that struggle against religion was indirectly a fight against an unjust and exploitative world. Religion is an opiate because it produces in us Illusions about our real situation in the world, the type of world we live in, and what, if anything, we can do to change it. The struggle against religion is not just an intellectual struggle against a system of beliefs we think to be incorrect. Marxists are not secular humanists who don't see a connection between the struggle against religion and the social struggle. This is why Marx maintains that, "The demand to give up illusions about the existing state of affairs is the demand to give up a state of affairs which needs illusions." That is to say, he wants to abolish religion in order to achieve real happiness for the people instead of illusory happiness. We will see that when Marx, Engels or Lenin use the word "abolish" they do not mean that the government or any political party should use force or coercive measures against people who are religious. What they have in mind is that since, in their view, religion arises as a response to inhumane alienating conditions, the removal of these conditions will lead to the gradual dying out of religious beliefs. Of course, if the Marxist theory on the origin of religion is incorrect, then this will not happen and religion will not be abolished. At any rate, this is what Marx means when he says, "Thus the criticism of heaven turns into the criticism of the earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics." We should also keep in mind that in addition to the theory of the origin of religion, Marx, Engels and Lenin were most familiar with organized religion in its most reactionary form as a state supported church representing the most unprogressive and backward elements of the ruling classes. "Quakers", for example, does not appear as an entry in the subject index to Lenin's Collected Works. They are not thinking about religion as a positive force as we might today: as for example the Quakers in the antislavery movement or the Black church in the civil rights movement. [Although Engels had positive things to say about early Christianity in the time of the Roman Empire.] These would have appeared to them as aberrations confined to a very tiny minority of churches. Sixty six years after Marx published his remarks on religion, Lenin addressed these issues in an article called "The Attitude of the Worker's Party to Religion" (CW:15:402-413), published in the paper Proletary in 1909. In his article, Lenin categorically states that the philosophy of Marxism is based on dialectical materialism "which is absolutely atheistic and positively hostile to all religion." There is no room for prisoners here! "Marxism has always regarded," he writes, "all modern religions [he remembers Engels liked the early Christians] and churches, and each and every religious organization, as instruments of bourgeois reaction that serve to defend exploitation and to befuddle the working class." I don't think we could have that opinion today. I mentioned above the role of the Black churches in the civil rights movement and we also know of many religious organizations and churches that have been involved in the peace movement and have taken stands in favor of workers rights and other progressive causes. In dialectical terms, what in 1909 appeared as two contradictory approaches has now become, in many cases, a unity of opposites. While Lenin's comments are, I think, on the whole still correct about the role of religion, we must admit that there are now many exceptions and that Lenin would probably not formulate his views on religion in quite the same way today. Be that as it may, religion would still be seen as an illusion to overcome by a proper materialist worldview. This does not mean that Lenin would have been hostile towards people having religious beliefs. He is very clear, following Engels, that to wage war against religion would be "stupidity" and would "revive interest" in it and "prevent it from really dying out." The only way to fight religion is by basically ignoring it and simply carrying on the struggle against the modern system of exploitation (capitalism). Those so-called revolutionaries who insist on proclaiming that attacking religion is a duty of the workers' party are just engaging in "anarchistic phrase-mongering." We have to work with all types of people and organizations to build the broadest possible democratic people's coalition. Still following Engels views, Lenin says the proper slogan is that "religion is a private matter." Elsewhere he writes ["Socialism and Religion" in the paper Novaya Zhizn in 1905: CW:10:83-87], that to discriminate "among citizens on account of their religious convictions is wholly intolerable." He maintains the state should not concern itself with religion ("religious societies must have no connection with governmental authority") and that people "must be absolutely free to profess any religion" they please, including "no religion whatever" (atheism). Would that socialist states (among others), past and present, followed Lenin's philosophy on this matter. Lenin sounds positively Jeffersonian! Jefferson in his second inaugural address (1804) proclaimed, "In matters of religion, I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the constitution independent of the powers of the general government." This is in line with Jefferson's 1802 comments about the "wall of separation between church and state." And what does Lenin say? He says the "Russian Revolution must put this demand into effect"! "Complete separation of Church and State is what the socialist proletariat demands of the modern state and the modern church." However, what is true for the state and the citizen is not true for the worker's party. Religion is a private matter in relation to the state but not in relation to the party. To think otherwise, Lenin says, is a "distortion of Marxism" and an "opportunistic view." Therefore, the party must put forth its materialist philosophy and atheistic world view and not try to conceal it from view. But this propaganda "must be subordinated to its basic task-- the development of the class struggle of the exploited masses against the exploiters." This basic task also means that workers with religious views must not be excluded from joining the party, and, indeed we "must deliberately set out to recruit them." Not only do we want to recruit them as part of the work of building a mass movement and mass party, "we are absolutely opposed to giving the slightest offence to their religious convictions." People are educated in struggle not by being preached to. This means that valuable party time should not be taken with fruitless debates on religious issues, but with organizing the class struggle. Finally, Lenin says there "is freedom of opinion within the party" but this does not mean that people can use this freedom to disrupt the work of the party. So, I conclude that, outside of the realm of theory, Marxists are not hostile to religion per se and are willing and eager to work together with all types of progressive people, religious or not, who will struggle with them in the current fight against the ultra-right and in the eventual fight, of which the current struggle is a part, for the establishment of socialism. About the Author: Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. This article was originally published in 2005 by Political Affairs