|

7/15/2021 20 Years of U.S. Occupation Was Brutal in Afghanistan—And So Will Be the Exit. By: Sonali KolhatkarRead NowAlongside the relief of ending the longest war in modern American history, we need to acknowledge the horrors of what we are leaving behind in Afghanistan. When a reporter in early July asked Joe Biden a question about the war in Afghanistan, the U.S. president sniped back, saying, “I want to talk about happy things, man.” Biden revealed, perhaps unintentionally, that the situation in Afghanistan is anything but a happy topic. It might have been one of the most revealing responses from a sitting president about the longest-running war in modern United States history. The president shifted focus, saying, “The economy is growing faster than anytime in 40 years, we’ve got a record number of new jobs, COVID deaths are down 90 percent, wages are up faster than any time in 15 years, we’re bringing our troops home.” The war’s end is merely the icing on the cake he is seemingly gifting the American public: an end to a war in addition to peace, prosperity, and health at home (even if such achievements are more marketing than reality). At the very least, one can give Biden credit for formally ending the U.S. role in the war, even if he had nothing substantive to say about the devastation we have wrought over the years. Members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus said they “commend President Biden for fulfilling his commitment to ending the longest war in American history” and took his withdrawal of troops to mean that “there is no military solution in Afghanistan.” (They made no mention of Biden’s role during the Obama presidency in prolonging the war.) Opponents of the war have known since 2001 that there is no military solution to the U.S.-sponsored fundamentalist violence that had plagued Afghanistan at the time. More such violence—which is largely what the U.S. offered for nearly 20 years—only made things worse. In announcing the war’s end and pivoting to what he deemed were “happy” topics, Biden fed the “propaganda of silence” that my co-author James Ingalls and I referred to in the subtitle of our 2006 book Bleeding Afghanistan. There has long been a deliberate effort to downplay the U.S.’s failures and paint a rosy picture of a war whose victory has always been just around the corner. But there is no happy ending for Afghans, and there was never meant to be. Afghans, already weary of never-ending war in 2001, were promised democracy, women’s rights, and peace. But instead, the U.S. offered elections, a theoretical liberation of women, and an absence of justice while championing corrupt armed warlords and their militias. In trying to end the debacle, American diplomats refused to involve the (admittedly flawed) Afghan government that they had helped to build as a bulwark against fundamentalism, and instead engaged in peace talks with the Taliban—the same “enemy” of democracy, women, and peace that the U.S. had spent nearly two decades fighting. Now, as the fundamentalist fighters claim more territory than they have controlled in decades, and the Taliban have predictably begun reimposing medieval-era restrictions on women, ordinary Afghans, including women, are taking up arms to fight them. Was this the liberation that the U.S. promised Afghan women? Even the manner of withdrawing American troops was as shameful as the mess the U.S. is leaving behind. The Associated Press reported that the U.S. military abandoned Bagram Airfield in early July in the dead of night, failing to properly coordinate with the Afghan army commanders who were expecting to take over. After they left, a “small army of looters” rifled through the millions of taxpayer-funded items left behind by American troops including small weapons and ammunition. Later on, one Afghan soldier bitterly told the AP, “In one night, they lost all the goodwill of 20 years by leaving the way they did, in the night, without telling the Afghan soldiers who were outside patrolling the area.” Afghans have every reason to be cynical. “The Americans leave a legacy of failure, they’ve failed in containing the Taliban or corruption,” said one shopkeeper in Bagram. Another auto mechanic told Reuters, “They came with bombing the Taliban and got rid of their regime—but now they have left when the Taliban are so empowered that they will take over any time soon.” Phyllis Bennis, director of the New Internationalism Project at the Institute for Policy Studies, explained to me in an interview that there is a likelihood of civil war breaking out but warned, “I think it would be a mistake to see it as a new civil war.” Bennis, who is the author of several books including Understanding ISIS and the New Global War on Terror and Ending the U.S. War in Afghanistan, added, “This would be in a sense a continuation of the existing civil war.” By that, she meant that for the past 20 years, the U.S. has essentially been inserting itself into an existing civil war between the Taliban and fundamentalist Northern Alliance warlords who had enjoyed previous U.S. support. The Taliban had won that war in 1996, “not because of the extremism of their definitions of religious law, but despite that,” said Bennis. But in 2001, after the September 11 attacks, the U.S. restarted that civil war by bombing Afghanistan and bringing the Northern Alliance warlords back into power along with a puppet government in Kabul. More than 200,000 lives and $2 trillion later, the U.S. is leaving the same basic dynamic largely in place. Most wars are a farce. But if ever there was a textbook case to be made about the futility of war, the 20 years of U.S. militarism in Afghanistan offers a shining example. Former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta in an opinion piece on CNN.com repeated the same list of tired and empty achievements that other defenders of the war have made: “the establishment of a democratic government, expanded rights for women, improved education, and successful operations to decimate core Al Qaeda and bring Osama Bin Laden to justice.” But then he went on to cite all the ways in which these seeming successes have unraveled and that the only way to prevent the Taliban from fomenting future violence is to “continue counter terrorism operations.” The narrow spectrum of actions that American elites have offered on Afghanistan ranges from Biden’s idea to withdraw forces (while pretending everything is happy), to an unending military presence as per Panetta. In other words, Afghans were never meant to have their happy ending. War and militarism do not offer such a solution. One cannot bomb a nation into democracy, women’s rights, and peace. Those things are built internally by civil-society-led institutions and networks free from violence, and that are engaged, supported, funded, and nurtured. Over 20 years, the U.S. cared little for such things. To its credit, the Congressional Progressive Caucus demanded from Biden that in addition to withdrawing troops, “The U.S. must support peace and reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan.” In their statement, lawmakers said, “we encourage the Biden administration to quickly put in place a multilateral diplomatic strategy for an inclusive, intra-Afghan process to bring about a sustainable peace.” But there appears to be little appetite for such solutions within the Biden administration. And Americans remain largely blissfully ambivalent either way. If only Biden, Panetta, and others had the courage to admit that the war in Afghanistan was ultimately an exercise in American imperialist hubris. It was an expensive and deadly smackdown of a poor nation that dared to host a terrorist faction that attacked the U.S., a costly message to the world that an attack on the U.S. will not go unpunished. That is all it was designed to do, and when histories of the war are written, one can only hope that this stark fact is made crystal clear. Most ordinary Afghans understand this even if Americans don’t. “We have to solve our problem. We have to secure our country and once again build our country with our own hands,” said Gen. Mir Asadullah Kohistani, the new commander of Bagram Airfield. Sayed Naqibullah, the shopkeeper interviewed by Reuters, echoed this claim, saying, “In a way, we’re happy they’ve gone… We’re Afghans and we’ll find our way.” AuthorSonali Kolhatkar is the founder, host and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute. This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute. Archives July 2021

0 Comments

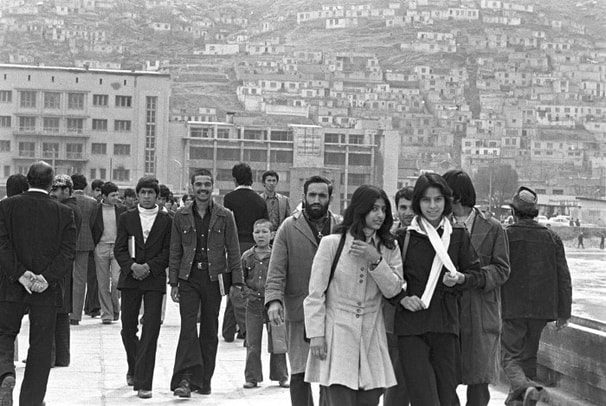

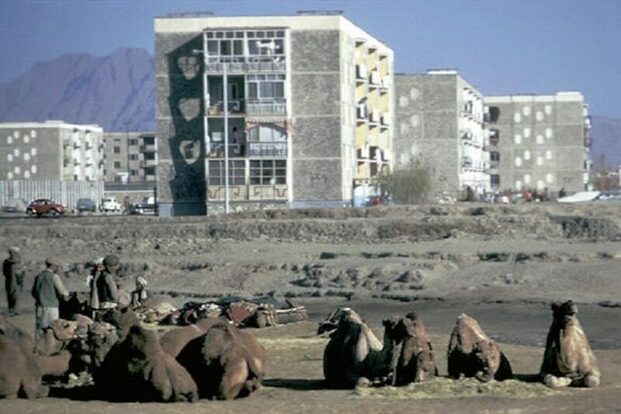

4/16/2021 Afghanistan’s Socialist Years: The Promising Future Killed Off by U.S. Imperialism. By: Marilyn BechtelRead NowWomen attend a rally in Kabul in the late 1970s. | Imgur via Pinterest In the mid-1970s and early ’80s, People’s World correspondent Marilyn Bechtel was editor of the bimonthly magazine, New World Review. She visited Afghanistan twice, in 1980 and 1981. The article below first appeared in our pages on Oct. 6, 2001—the day before the U.S. launched its war in Afghanistan—under the headline, “Afghanistan: Some overlooked history.” With the Biden administration now withdrawing all troops from the country, we present this article as a reminder that the U.S.’ longest war had roots that went beyond the terrorist attacks of 9/11, stretching back to Cold War anti-communism. Since the horrific events of Sept. 11, much has been said about the desperate situation of the Afghani people now crushed under the heel of the theocratic, dictatorial Taliban, and about the role of the Northern Alliance and other Taliban opponents who now figure in Washington’s plans for the region. Kabul street scene, 1979. | TASS There has been talk, most of it distorted, about the role of the Soviet Union in the years from 1978 to 1989. There has been talk, most of it understated, about the role of the U.S. in building up the Mujahideen forces, including the Taliban. But almost no one talks about the effort the Afghan people made in the late 1970s and ’80s to pull free of the legacy of incessantly warring tribes and feudal fiefdoms and start to build a modern democratic state. Or about the Soviet Union’s role long before 1978. Some background helps shed light on the current crisis. Afghanistan was a geopolitical prize for 19th-century empire builders, contested by both czarist Russia and the British Empire. It was finally forced by the British into semi-dependency. When he came to power in 1921, Amanullah Khan—sometimes referred to as Afghanistan’s Kemal Ataturk—sought to reassert his country’s sovereignty and move it toward the modern world. As part of this effort, he approached the new revolutionary government in Moscow, which responded by recognizing Afghanistan’s independence and concluding the first Afghan-Soviet friendship treaty. From 1921 until 1929—when reactionary elements, aided by the British, forced Amanullah to abdicate—the Soviets helped launch the beginnings of economic infrastructure projects, such as power plants, water resources, transport, and communications. Thousands of Afghani students attended Soviet technical schools and universities. After Amanullah’s forced departure, the projects languished, but the relationship between the Soviets and the Afghans would later re-emerge. The Center for Science and Culture was built in Kabul as a gift from the people of the Soviet Union. Once U.S.-backed Mujahideen forces took power, the facility was destroyed. | TASS In the 1960s, a resurgence of joint Afghan-Soviet projects included the Kabul Polytechnic Institute—the country’s prime educational resource for engineers, geologists, and other specialists. Nor was Afghanistan immune from the political and social ferment that characterized the developing world in the last century. From the 1920s on, many progressive currents of struggle took note of the experiences of the USSR, where a new, more equitable society was emerging on the lands of the former Russian empire. Afghanistan was no exception. By the mid-’60s, national democratic revolutionary currents had coalesced to form the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). Modern apartment buildings constructed in Kabul in the 1980s with Soviet assistance. | TASS In 1973, local bourgeois forces, aided by some PDP elements, overthrew the 40-year reign of Mohammad Zahir Shah—the man who now, at age 86, is being promoted by U.S. right-wing Republicans as the personage around which Afghanis can unite. When the PDP assumed power in 1978, they started to work for a more equitable distribution of economic and social resources. Among their goals were the continuing emancipation of women and girls from the age-old tribal bondage (a process begun under Zahir Shah), equal rights for minority nationalities, including the country’s most oppressed group, the Hazara, and increasing access for ordinary people to education, medical care, decent housing, and sanitation. A Mujahideen Islamist fighter aims a U.S.-made Stinger missile supplied by the CIA near Gardez, Afghanistan, December 1991. | Mir Wais / AP During two visits in 1980-81, I saw the beginnings of progress: women working together in handicraft co-ops, where for the first time they could be paid decently for their work and control the money they earned. Adults, both women and men, learning to read. Women working as professionals and holding leading government positions, including Minister of Education. Poor working families able to afford a doctor, and to send their children—girls and boys—to school. The cancellation of peasant debt and the start of land reform. Fledgling peasant cooperatives. Price controls and price reductions on some key foods. Aid to nomads interested in a settled life. I also saw the bitter results of Mujahideen attacks by the same groups that now make up the Northern Alliance—in those years aimed especially at schools and teachers in rural areas. The post-1978 developments also included Soviet aid to economic and social projects on a much larger scale, with a new Afghan-Soviet Friendship Treaty and a variety of new projects, including infrastructure, resource prospecting, and mining, health services, education, and agricultural demonstration projects. After December 1978 that role also came to include the introduction of Soviet troops, at the request of a PDP government increasingly beset by the displaced feudal and tribal warlords who were aided and organized by the U.S. and Pakistan. The rest, as they say, is history. But it is significant that after Soviet troops were withdrawn in 1989, the PDP government continued to function, though increasingly beleaguered, for nearly three more years. Somewhere, beneath the ruins of today’s torn and bloodied Afghanistan, are the seeds that remain even in the direst times within the hearts of people who know there is a better future for humanity. In a world struggling for economic and social justice—not revenge—those seeds will sprout again. AuthorMarilyn Bechtel writes for People’s World from the San Francisco Bay Area. She joined the PW staff in 1986, and currently participates as a volunteer. This article was first published by People's World.

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed