|

10/27/2020 Human Rights Defenders Fight to Protect Immigrants In Detention Amid Covid-19 Pandemic. By: Maddy HughesRead NowSince nearly the beginning of the Trump administration’s immigrant family separations in 2017, the ICE Detention Center in Aurora has been the subject of much speculation in the media. The facility, owned by private prison corporation GEO Group, is funded through a high sum in tax dollars and has been found to still overspend its budget. Despite the $7.5 billion that ICE spent in 2018 and $7.6 billion in 2019, there were a list of issues documented by the U.S. Inspector General in 2019 including incidents of mumps and chickenpox spread among inmates. Now, with the COVID-19 pandemic, there are worries that the detention center is a breeding ground for infection. In September of 2019 the ACLU of Colorado released a report citing human rights abuses and neglect at the facility that led to the deaths of two detainees. Kamyar Samimi, a 64-year-old man who was held in detention for 15 days before he passed, had been on methadone for 20 years and complained repeatedly of severe withdrawal symptoms to nurses. His complaints elicited almost no response. Had Samimi been given his medication, or never been taken off of it in the first place, he would have likely survived. Evalin-Ali Mandza, 46 years old, was in detention at the Aurora GEO Center in 2012 when he suffered a heart attack in the early morning. Because the ICE nurse on staff did not know how to use an electrocardiogram machine, nor how to read the test results, there was a delay in the decision to call for an ambulance. An investigation by the Department of Homeland Security found that staff also did not use proper Chest Pain Protocol, and Mandza wasn’t given cardiac medication. All these factors “may have been contributing factors to the death of the patient,” per the report. GEO Group CEO George Zoley seems to believe GEO’s operations are going well. The ACLU report notes that Zoley, who immigrated from Greece to the USA with his family when he was only three, announced in a February 2019 conference call with shareholders that he was “pleased with (GEO’S) overall operational and financial results during the very active fourth quarter of 2018.” During the call, he also proudly shared that the GEO Corrections and Detention unit served over 300,000 individuals in 2018. Net income for the fourth quarter of 2018 was $33.4 million. Local immigration rights activists disagree about what it means to “serve” inmates in ICE’s facilities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, activists have been concerned about spreading of the virus in detention centers. Ana Rodriguez, community organizer with Colorado People’s Alliance, talks regularly with people in the Aurora facility. At the beginning of the pandemic, inmates told her they weren’t even receiving clean towels. “They didn’t have anyone doing laundry service. This virus requires excellent personal hygiene. How are you supposed to stay clean and protected if you don’t even have a clean towel to use?” On March 27th, one of the detainees she talks to regularly told her that GEO guards gave the detainees written notices stating that they would be placed on 23 hour lockdowns in their cells and would be let out in groups so they could “adhere to Governor Jared Polis’” directive for detention centers. “For weeks, detainees were in their cells around 23 hours a day. The one hour they were allowed out was their only time to call family, attorneys, shower, etc. Some cells were even forgotten to be let out so they were stuck in their cells more than one day. Others were only allowed out 20 or 30 minutes instead of the full hour.” GEO claimed they were following social distancing guidelines, but at the time, they were keeping six to eight inmates in one cell. “That literally made it impossible for them to practice social distancing within their own cells for the 23 hours they were locked down per day. Even if they stood in different corners of the cell, they wouldn’t be able to be six feet away from each other,” Rodriguez says. In response to the news about inmates being grouped together in their cells, community organizations like COPA (Colorado People’s Alliance), AFSC (American Friends Service Committee), family members of detainees, and more allies made noise about the issue. They used social media, press releases, and contacted Congressional offices. After a few weeks, GEO started allowing detainees four hours out of their cells per day instead of just one. They were also spread out so cells had two to three people, but some cells still hold four to six people. COPA pressed Congressman Jason Crow’s office to ask why they couldn’t further spread detainees out and use every single cell. “They heard back from GEO that they couldn’t share that information because it was contractual with ICE. This made it seem as if they had no control over how spread out people were and it was ICE’s fault because that’s what the contract said.” And there was still a problem with the schedule inside the facility. “The problem was that GEO’s schedule was so poorly planned that for several weeks, at least once every few days some of the cells would not be released for 32 consecutive hours. The folks in these cells were released one day from 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m., and would remain in their cells from 11 am until 7 pm the next day when they would be released from 7 pm to 11 pm.” This issue also required pressure from the outside to change. “Detainees created an alternative plan in a grievance that they submitted to the Major. They are supposed to hear back within five days. But they were getting radio silence.” Congressman Crow’s office stepped in at Rodriguez’s request, and asked GEO for information on their release schedules. “We also published this testimony on our social media and talked about it in our actions. Within a few days of the Congressman’s office asking for GEO’s cell release schedules, I got a message from my detained friend telling me that GEO had reorganized their schedules and they were now being released four hours in the morning and four hours in the evening.” Rodriguez has been organizing to increase transparency and accountability from ICE for two years now. She says her work, and community pressure, has gotten results. “The first year was about building relationships and hearing families’ stories, partly through canvassing outside the detention center. In October 2019 a local level ordinance was passed. In December 2019 the Pod Act was passed. And there’s been all of the work done with Jason Crow. Now community members in other places have precedent to use their Congress members to hold GEO accountable.” The local level ordinance mentioned requires ICE to report contagious disease outbreaks to the fire department. It is intended to protect first responders who may risk their health while visiting the facility on the job. The POD Act (Public Oversight of Detention Centers) allows members of Congress access to detention centers within 48 hours of their request. Congressman Jason Crow’s office does weekly visits to the Aurora ICE detention center to check on conditions in the facility. Rodriguez has heard from the fire chief that ICE has been reporting, per the ordinance, during the pandemic. However, she says, “Only two people have been tested. So the ordinance isn’t enough.” Rodriguez says that in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, she hears from people all over with loved ones who are detained. “Most recently I’ve been hearing from folks in California, Utah, Ohio. People are really panicked about what’s happening to their loved ones during the pandemic. In some cases they haven’t seen them in person since they were brought into the facility. They call me in desperation, saying, ‘I don’t know what’s happening,’ worried about their loved ones with asthma, saying people are getting sick and could die in there and the guards aren’t doing anything. They want me to check on (their loved ones).” Rodriguez would like to see a state policy to bring facilities under the responsibility of the state. “State facilities are important because GEO does not have official inspections. Reports on Congressman Jason Crow’s website are done by his staff, so they’re allowed to go through the kitchen for example and check for temperature of food. But imagine if you were hired onto Crow’s staff and on your first day, you had to go do an inspection of the Aurora ICE detention facility.” In other words, Crow’s staff is not trained for health inspections, especially during the time of a major health pandemic. “It would be much more thorough if a designated agency, like CDPHE, did it. They would have a laundry list of things they’re inspecting for.” Can ICE detention centers practice CDC safety guidelines well enough to contain the virus? From Rodriguez’ perspective, it’s not possible. “Having people in close quarters and in these for-profit detention centers will lead to inefficient care; they will always cut corners and choose the cheaper option versus the humane option. It’s inevitable that they will get sick in these facilities.” Medically vulnerable detainees are being released early due to a federal judge’s order, and as of Tuesday April 21st, ICE said they had already released 700 at-risk detainees. Rodriguez says this is not enough. “They have legal authority to use parole and let people go home to their families and continue ICE check-ins. It’s a preliminary injunction, and makes it clear that they’re not using basic tools at their disposal because people are not their priority.” She notes that there are many community organizations whose purpose is to provide direct service; help with placements, plane trips, and post them while this crisis is in place. “ICE should use every tool they have to get people out, to get them back to their families. That’s what our tax dollars should go to. Owners are making millions of dollars a year off our tax dollars to profit off these detention centers.” The order that ICE consider releasing medically vulnerable detainees early happened a week after RMIAN (Rocky Mountain Immigrant Advocacy Network), Arnold & Porter, and NIPNLG (National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild) lawyers filed a federal lawsuit to release 14 detainees who were “at severe risk of serious health complications or death should they contract COVID-19.” Laura Lunn, an attorney at RMIAN, said that their lawsuit was similar to the case that caused a federal judge to order to release vulnerable detainees early. “That case provides a wonderful framework, this is the first time that something like that is happening,” she said. Eight of the 14 people in the lawsuit were released the day after the group filed suit. Six were denied release. “What’s striking about the group of people they released is they are all living with HIV, but they did not release another person living with HIV,” Lunn said. “It’s really hard to say what other factors they could be considering. Four of them have criminal history and two do not. Some of them have criminal history from over a decade ago, and this is civil detention, not criminal custody. None of them are serving a sentence, so there’s not a known end date to their confinement. They are being held before they go to immigration court. The government’s purpose that they go to court is not being met because they can’t go if they’re sick.” Lunn added that a July 2019 report by the Congressional Research Service titled “Immigration: Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs” notes that 99 percent of participants in Intensive Supervision Appearance Program III (ISAP III) showed up for their court hearings. And between the fiscal years of 2013 and 2017, 92 percent of asylum seekers showed up in court to hear the final decision on their claims. Lunn says that she doesn’t think the federal judge’s injunction is going to be effective. “Most of our clients have had their parole requests denied by ICE; we don’t believe that they’ll change their minds just because a judge says they need to re-review their cases. We want the district courts to make a ruling where a judge says, ‘Absolutely, you must release them.’ When you boil it down, they are the custodians and they have already decided to hold these people in their custody. The litigators will have to keep going back to court to make sure the judge is enforcing the order. ICE is going to have a conservative reading of that order. We don’t have time for the judge to create more clarity around his order when people’s lives are hanging in balance, we need a judge in Colorado to say their lives matter and they need to get out of ICE custody now. One of the plaintiffs in the case Lunn worked on, who wished to remain anonymous for the sake of her asylum case, is a transgender woman who came to the USA border on March 13th at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. She fled her country of origin “because of the transphobic violence that is criminal and threatened with death by gangs.” She crossed a bridge from El Paso and requested a number to enter COESPO. She was detained right away and transferred to Montana, then Arizona, finally ending up at the Aurora detention facility. She said that detention had a significant effect on her health. “For me, it was very traumatizing. I have HIV and I started sinking into a depression and a lot of fear. I felt how my immune system started getting weaker, people with HIV can really feel that. I was very fearful of getting sick. The norms were not good, it wasn’t clean, and too many people were placed together.” She was lucky to have pro bono attorneys working her case. “We had to file a lot of grievances against GEO, especially during the pandemic. We had to make a lot of denunciations (against ICE) with attorneys because many of our group of women are HIV positive, so any infection can really harm us in the detention center. There was no cleaning, no detergent. Our immune system was already down from the stress of being detained, so the risk (of contracting) coronavirus was even higher.” “Seven trans women are still there, two of them have been for over a year. One of them has diabetes. I ask that ICE be more flexible with trans women. All of us carry a lot of hardship and have problems from our home countries. Sharing our stories over and over with officers, I always started crying because every time I have to repeat it, it’s like I have to live it again. They ask us again and again to see if we’re trying to lie. I wish they were more sensitive.” When she entered the country, she thought she was doing the right thing. “We voluntarily gave ourselves over to immigration, we’re trying to follow the process, we should be treated more sensibly.” She explained that she doesn’t think detention centers should be the solution for all immigrants. “There should be a different type of detention center. We are all mixed together; people in red jumpers have committed crimes, and (people in) orange jumpers have broken some law, but we’re all in there together. When they arrested me, they treated me like a criminal. I had never been arrested in my life. We were handcuffed in the airplane, like we would try to escape.” “Everything I experienced with ICE has been traumatizing. I didn’t think it would be that way. For example, another trans woman and myself were singled out by officers and told we needed to go wash our faces. We just didn’t think us having makeup had anything to do with this process. Some guards kept saying you are men, you aren’t women. They would make us take off our bras because we don’t have breasts.” As an immigrant rights attorney, Lunn’s main concern is the health and safety of detainees. She doesn’t know why more people haven’t been tested for the virus. “That’s something you should ask ICE. I don’t know why they haven’t tested more people. Anecdotally our clients have noted that many people are coughing, sneezing, have fevers, have difficulty breathing. That’s what’s fueling the fear they experience each day because they see so many sick people around them. One of our clients has said that there has been intermingling between dorms in the facility. All of the dorms are understaffed because a lot of staff members are not coming to work. One of our clients has one lung as well as asthma, so she could easily die from the virus but she cannot easily control who she’s exposed to on a daily basis.” She says oversight of the facilities is a band-aid. “As of April 17th a GEO employee tested positive so that same day they started practicing quarantine inside that pod. But no detained setting is appropriate during a pandemic because it’s impossible to practice social distancing. Even if you make sure no one else is going in and out, staff is coming in and out every day and not wearing PPE. There are still people being detained and brought into the facility by ICE. 20 percent of people infected show no symptoms but still can transmit it. Even if they’re doing temperature checks and telling staff to stay home, it’s not preventing the spread. Vulnerable people will suffer health complications for the rest of their lives. TIME looked at the whole prison system in Ohio and 78 percent of inmates had it. When you boil it down the government has argued that our clients are not better outside detention than in it.” “Medicine doesn’t support the claims the government is making. Our clients are saying the people bringing them food are not wearing face masks and their food is uncovered. So they say, ‘What risks am I facing just by nourishing my body?’ All the comforts we have through this pandemic are stripped from our clients so emotionally they are better off not in detention.” During the time of COVID-19, only detainees with added health issues are being considered for early release. But all detainees are reliant on staff to follow CDC guidance, especially because they don’t receive updates on best safety practices themselves, according to Lunn. “The main outlet people have to understand any of this is through the news and our clients don’t have control over the flow of information that they’re receiving,” Lunn said. Some detainees still do not have legal representation for their cases in this time of elevated health risk. Claudia Robles, a USA -born citizen, says she has spent $15,000 on legal help for her husband who was detained in November of last year. When his case was denied, she took matters into her own hands. “On March 17th, Luis was denied his cancellation of removal by a GEO ICE judge. I could not afford a lawyer anymore so I had to help my husband file his own appeal to see if somebody else can take a look at the case and see that the judge made a bad call that my husband should have to leave the country just because she thinks that he’s a bad husband, which he is not. That was her reasoning for denying his cancellation of removal. I disagree, my husband is the rock of our family. He completes us and we feel empty without him with us.” Claudia and Luis have a four year-old daughter together, and with schools closed until next year due to the pandemic, and her husband detained, Claudia will have to pay for private day care until schools open. Claudia calls herself the “bread-winner” of the family: “I work as a medical assistant in my local urgent care (clinic). I am an essential worker in this pandemic,” she said. Claudia has no idea when her husband will be released, though she is worried for his health, as he suffers from asthma. “It’s been super hard to have Luis in GEO knowing he gets spoiled food and not enough food. I barely sleep just worrying about his health and well being, especially now that in this pandemic my husband has to share his cell with five other people. If he gets COVID-19, that could be deadly, since it’s a virus that affects his lungs which are already compromised due to his asthma.” Claudia and her daughter have not been able to see her husband since the pandemic began. “We have no information of when he will be released because he was denied bond twice by the same judge that denied his cancellation of removal. Before the pandemic his visiting days were Tuesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. My daughter and I went every Saturday to go see my husband since he has been there. The last time we were able to see him, behind glass of course, was on March 8th. My daughter is very sad and tells her dad every day how much she misses him and misses seeing him even though it was behind glass. She never understood why she wasn’t able to hug and touch her father, why she had to talk to him through glass and hear his voice through a phone.” Claudia may have to wait through the whole pandemic for Luis to be released. “We’re waiting to hear if his case is going to be able to be appealed. They told us that it could take six months to a year for a response, which means my husband would have to be in detention that whole time until we heard back to see if his case would be able to be appealed. We are trying to do a humanitarian parole right now for him but it seems that GEO has been returning all the legal documents that I’m trying to send my husband so that he can apply for humanitarian release due to having asthma. Hopefully soon this information will finally get to him and he will be able to file for humanitarian parole and be able to come home until we can hear from the appeal.” For the foreseeable future, detainees, their families, and immigrant advocates will be counting on the mercy of ICE to release those on the inside with added health risks. When asked for comment, Pablo E. Paez, Executive Vice President of Corporate Relations, replied, “As a service provider to the federal government, we would refer you to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement for specific answers to your questions, as well as the agency’s latest guidance on COVID-19. Our company has taken comprehensive steps to address and mitigate the risks of COVID-19 to all those in our care and our employees as detailed in our public statement at geogroup.com/COVID19.” About the Author:

My name is Maddy. I am a journalist, writer, and thinker based in Colorado where I work as a stringer for a small-town newspaper and have some odd jobs on the side. I am a member of the Democratic Socialist of America and am interested in bringing a lens of intersectionality to journalism and "pushing the envelope" to make people think critically about social issues. I love animals, music, food, creative writing, and the outdoors. She/her.

0 Comments

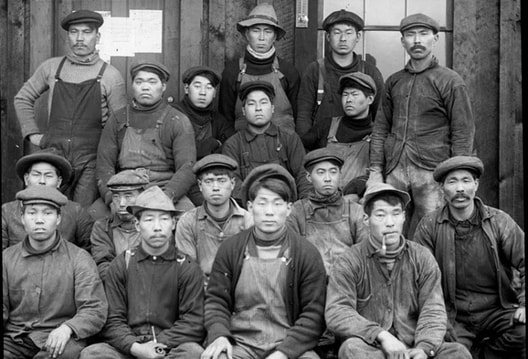

In my last essay, I discussed how capitalist hegemons have used their control over food supply to shape rules of international commerce. I also demonstrated how these policies have led to economic shocks and displacement in developing countries, leading to mass migration in search of economic opportunity. I believe this history is essential to understand the migration that has been a focal point of American and European politics in recent years. In this essay, I will attempt to explore the issue of migration in capitalist development, hoping to provide historical context for our current conceptions and policies around immigration. One of Marx and Engels's favorite examples was that of the Irish. Up until the mid-19th century, Irish society was structured around a system of tenant farming with most of the land owned by English and Anglo-Irish families. This landed gentry introduced the potato to Ireland in the mid-1700s as a subsistence crop for the rural poor; by the 1840s it had become the staple crop of Ireland with much of the population nearly completely dependent on the potato for their diet. Thus, when the potato blight hit in 1845, the Irish were left with little to eat, even though they were still exporting various agricultural commodities to England. During and after the famine, the British aristocracy took the opportunity to push small-landholders off their land.[1] As Marx put it, "If any property it ever was true that it was robbery, it is literally true of the property of the British aristocracy. Robbery of Church property, robbery of commons, fraudulous [sic] transformation accompanied by murder, of feudal and patriarchal property into private property."[2] The result was the death of nearly 1 million Irish and the additional emigration of 1 million more. Thousands of these newly-landless Irish, migrated to English cities seeking any form of economic opportunity.[3] As I pointed out in my last essay, this sudden influx of workers allowed British capitalists to supplement their industrial reserve army with an injection of a subordinate group to perform degraded labor, intensifying competition in the labor market and driving down wages. Stoked by members of the bourgeoisie to divide the working class, anti-Irish sentiment spread rapidly across England, with violent attacks against Irish migrants becoming commonplace. This stance is probably best exemplified by Benjamin Disraeli who wrote in 1836: "[The Irish] hate our order, our civilization, our enterprising industry, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain and superstitious race have no sympathy with the English character. Their ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry. Their history describes an unbroken circle of bigotry and blood."[4] These same tropes have often been repeated in different ways and we have seen them reappear in modern American political discourse in recent years. Though billed as a "Land of Immigrants" in the modern liberal lexicon, the actual history of migration in America is much more muddied than this simple platitude indicates. As Aziz Rana put it: "Throughout American history, the tension between capitalism and both democratic self-government and economic independence has largely been resolved by native expropriation and/or racialized economic subordination."[5] From its inception the United States has been an experiment in what Rana and others refer to as "settler colonialism". Despite the proclamations of politicians extolling the American virtues of acceptance and equal opportunity, race and class have structured American societies from the earliest days of the Jamestown colony. During the early colonial period, British officials considered America a depository for their “excess” population, i.e. the poor. To encourage this “rubbish” to migrate to the “New World” the British government created a system of land-grants promising fifty acres to those who made the journey. At first, this helped promote equitable land distribution, but, with the establishment of the “headright system” in 1618, land was allotted based on the number of people whose travel expenses a settler paid for, granting fifty additional acres per head. This incentive, mixed with the large expense of the journey, led to the broad use of indentured servitude, with many of the early settlers coming to America via this arrangement.[6] Importantly, the additional land was given whether the servant survived their indenture or not- leading to extremely exploitative labor conditions. Obviously, this system of allocation led to a vastly unequal distribution of land with much of the best land accruing to the wealthy and politically connected. Eventually, most of the small farmers were squeezed out of the market resulting in a mass amount of landless poor who would become “squatters” in peripheral areas clearing land for subsistence farming. As formal British settlements expanded to these peripheral areas, squatters, who held no formal title to the land they cleared, were again pushed off their land repeating the process. Thus, it is no surprise that several founders, such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, saw western expansion as a necessary safety valve for excess population. This became a major point of contention between the colonists and the British following the acquisition of French territory in North America after the Seven Years’ War.[7] After signing the Treaty of Paris, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding all settlement in territory west of the Appalachian Mountains and designating this area as an “Indian Reserve”.[8] Not only did this limit western expansion, but many also feared having native civilizations so near British settlements. This is reflected in the Declaration of Independence where Jefferson accused England of having “endeavoured [sic] to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction of all Ages, Sexes, and Conditions.”[9] This statement is indicative of how the American project was conceived. From the earliest days of colonization American leaders have sought to manipulate the demographics of the growing nation, shaping who would be allotted full citizenship and who would not. With the addition of vast new western territories, via the Northwest Ordinance and the Louisiana Purchase, and the expansion of American industry, the young nation required new sources of immigrant labor to fuel western expansion and development. Thus, many early American capitalists supported broadly open immigration policies, with 33 million immigrants entering the U.S. between 1820 and 1920. Indeed, during much of the 19th century American industry was dependent on foreign labor with first- and second-generation immigrants constituting 57 percent of manufacturing[10] and 64 percent of mining laborers by the 1880s.[11] But before we wax poetic about America’s tradition of acceptance, we need to remember that this openness has always been qualified. As Suzy Lee argues: “Capitalists may prefer the opening of borders to the extent that immigration policy permits large flows of immigrant labor, but they also prefer an immigration system that does not confer many rights to these entrants.”[12] Essentially, business interests want to ensure a constant supply of disenfranchised workers who would then be forced into subordinated forms of labor. Traditionally, this subordinate labor had been supplied by natives, indentured servants, and African slaves; but, with the abolition of these variations of bonded servitude, a new system would need to be devised to serve the same function. In the 1860s, the federal government created the “United States Emigrant Office” to promote immigration and legalized the use of contract migration which was ultimately very similar to indentured servitude.[13] These policies were designed to attract migrants from Europe and Asia to work in eastern factories or, as was most common for the Chinese, to develop the west.[14] Between the years 1849 and 1880 the population of Chinese immigrants in the U.S. had grown from 650 to over 300,000.[15] Of course, this massive influx of Chinese people was accompanied by laws intended to ensure their status as a subordinated group, such as placing exorbitant taxes on foreign-born miners.[16] Importantly, Chinese immigrants were excluded from the Naturalization Act of 1870 which only extended citizenship rights to formerly enslaved black people, which also allowed many Western states to pass Alien Land Laws prohibiting “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from acquiring land.[17] Further, we see the U.S. system of deportation emerge with the passage of the Paige Act in 1875, which mainly targeted Asian women for deportation. This Nativist backlash to Chinese immigration was more direct in the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882, which placed a ten-year moratorium on all Chinese labor immigration and forbade any state from extending citizenship to Chinese resident aliens. Ten-years later, the Geary Act passed extending Chinese exclusion as well as requiring Chinese people to register and obtain a certificate of residence, without which they would be subject to deportation. The Geary Act was made permanent in 1902 and shaped immigration policy for the early decades of the 20th century.[18] The anti-Chinese sentiment of the time is reflected in Justice Harlan’s much celebrated dissent in the Supreme Court Case, Plessy v. Ferguson, where the justice proclaims: “There is a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race.”[19] Here we also see a notable shift in government policy towards “closing the gates”, made possible by the scarcity of remaining unsettled western land and growing mechanization in American industry, producing a domestic labor surplus and decreasing demand for immigrant labor. This change in policy was consolidated by the Quota Acts of the 1920s establishing a racialized quota system meant to favor immigration from European nations as well as creating systems of visas and deportation. However, certain industries, such as agriculture in western states, still depended on immigrant labor, leading Congress to exclude immigration from Mexican and other Latin American countries from the Quota Acts. These restrictions on immigration and the severity of enforcement would fluctuate depending on the labor needs of business. As Aziz Rana summarizes: “Most of the 20th century is state and corporate actors keeping the border fluid to ensure pliable labor supply from Mexico, then subjecting them to extreme forms of coercive violence in the U.S. when businesses view their labor as unnecessary.”[20] In the 1950s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS, precursor to ICE), campaigned to shift Mexican immigration flows away from unauthorized migration into formal channels such as the Bracero guest-worker program. This also provides us another example of early deportation systems, with the INS’s Operation Wetback, which involved the mass detainment of undocumented immigrants and immediately placing them in the formal guest-worker program.[21] The Bracero program, along with racial quotas and western-hemisphere exclusion were ended in the 1960s after a mass movement of organized labor and insurgent farmworkers successfully pressured policymakers. This temporarily weakened companies dependent on immigrant labor, but, eventually, this was compensated for by a reversion of immigration flows into undocumented channels, accompanied by the explosion of “undocumented” status for Mexican immigrants.[22] In the decades since the 1960s, Congress has passed various legislation attempting to increase border security and restrict unauthorized immigration to no avail. Border enforcement only captures approximately one-third of migrants attempting to cross and those who are not captured are more likely to remain instead of migrating seasonally. The result is an estimated population of 11 million undocumented immigrants residing in the U.S. effectively serving as a guest-worker program. To understand this shift in immigration policy we must also analyze the structure and effects of the neoliberal global order which has developed in recent decades. Aziz Rana describes it as: “The story about the profound global iniquities hard written into the international order, from which the U.S. gains the most benefit. The U.S. has constructed international legal arrangements that allows its capital to flow anywhere, while controlling immigration.”[23] As I described in my last essay, developed western nations, through control of food supply and global organizations such as the IMF and WTO, forced developing nations to undergo a process of economic restructuring, opening domestic markets to foreign commodities and investment. Thus, neoliberal policies, by destroying domestic industries and displacing mass amounts of people, have ensured an overwhelming surplus population used as a source of cheap labor. This is made possible by the concentration of capital into fewer, larger, transnational companies who can use this cheap labor to outsource parts of the production process to developing nations, leading to the “configuration of enclave economies operating as appendages in global commodity chains.”[24] Currently, between 55 and 66 million people in the southern hemisphere work in these types of enclaves. Corresponding with these neoliberal reforms in developing nations has been the restructuring of industrial relations in developed countries weakening labor-rights and expanding employer control. For companies this has meant greater discretion in wage determination, work organization, and decisions over hiring-and-firing. For the working class this has meant decreased job security, intensification of work, and stagnation of wages. In broader economic terms it has meant the expansion of differentiation and precarious employment in the global division of labor, devaluing the cost of labor and lowering wages. Precarious employment “is a type of employment that is unstable, insecure, and revocable.”[25] Currently, in the United States the percentage of workers employed part-time and under non-standard labor relations were around 17% and 10%, respectively, with over 1.5 billion people globally work in conditions of vulnerability.[26] These forms of employment are normally characterized by low pay, insufficient social benefits, and lack of legal labor protections, with this mass of insecure workers serving a similar function to Marx’s “Industrial Reserve Army”.[27] It is, therefore, no surprise that an increasing number of Americans report feeling insecure in their jobs.[28] And as many immigration scholars have pointed out, immigrants are the ultimate precarious workers, and, with the mass displacement neoliberal policies have wrought in developing nations, millions of workers have begun migrating to developed nations for economic opportunity. Though immigrant workers are technically entitled to the same labor protections as native workers, their ability to exercise these rights is contingent on permission to be present in the country. This is obvious in the case of undocumented immigrants, but even many authorized migrant workers are vulnerable to having their “legal” status changed to “illegal” if their employer sponsorship is revoked, making migrant groups ripe for exploitation.[29] These various aspects of the neoliberal world order have combined to cause the growth of job-insecurity and wage stagnation in developed nations, along with the mass exploitation of migrant workers and workers in developing nations. With this background in mind, how should we on the left respond to the growing nativist sentiment in American political discourse? First, we need to recognize the two dimensions of immigration policy as restrictions on migrant flows and the labor rights of those migrants. Second, we must acknowledge that these two dimensions cannot be fully separated and have a dialectical relationship. As we have seen, certain sectors of American industry (i.e. agriculture and service industry) are still dependent on securing flows of migrant workers, but they are also interested in restricting immigrant access to labor rights. It has therefore been tempting for many American politicians to focus on increasing rights of immigrants, while simultaneously supporting current restrictions on immigration. But, as I discussed above, access to these rights is contingent on permission to reside within the country. Further, as attempts at restricting immigration and expanding border security over recent decades have proven ineffective, even many of the industries dependent on immigrant labor, have become less resistant to migration controls. As it turns out, massive investments in militarized border security, broad deportation apparatuses, and detention facilities, may not do much to prevent or deter undocumented immigration, but they are effective at subjecting migrant workers to extreme forms of violence making them less likely to join in labor organizing. This shows that if we want to improve immigrant rights, we must also seek to deconstruct the national apparatus of immigration control and detention. This would allow migrant workers to exercise their labor rights and provide labor organizations with a mass of potential new members. This is significant because studies have shown immigrant workers are more likely to join unions than native workers and immigrants often work in the most vulnerable industries who cannot easily outsource labor.[30] In summation, I believe leftist policy should focus on promoting awareness of the neoliberal roots of the deteriorating living standards and working conditions experienced by the working-class over recent decades. This includes teaching the history of rising wages, strong job protections, and better working conditions resulting from labor organizing, and the way these benefits have been eroded by an assault on unions by employers and the government. Further, it must include opening borders and organizing workers in vulnerable industries. But most importantly, it will require solidarity with migrant workers, recognizing them as an asset rather than a problem. Citations [1] History.com Editors. Irish Potato Famine. 17 Oct. 2017, www.history.com/topics/immigration/irish-potato-famine. [2] Marx, "The Duchess of Sutherland and Slavery," New York Daily Tribune, February 9, 1853. [3] MOKYR, JOEL, and CORMAC Ó GRADA. “What Do People Die of during Famines: the Great Irish Famine in Comparative Perspective.” European Review of Economic History, vol. 6, no. 3, 2002, pp. 339–363. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41377928. Accessed 15 Sept. 2020. [4] Benjamin Disraeli, Letter to The Times [Q.d.], www.ricorso.net/rx/library/criticism/guest/Disraeli_B.htm. [5] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [6] Isenberg, Nancy. “Taking out the Trash: Waste People in the New World.” Essay. In White Trash, 17–42. Penguin USA, 2017. [7] Isenberg, Nancy. “Andrew Jackson's Cracker Country: The Squatter as Common Man.” Essay. In White Trash, 105–32. Penguin USA, 2017. [8]“Royal Proclamation, 1763.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/. [9] Thomas Jefferson, et al, July 4, Copy of Declaration of Independence. -07-04, 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib000159/. [10] Charles Hirschman and Elizabeth Mogford, "Immigration and the American Industrial Revolution From 1880 to 1920," Social Science Research 38, no. 4 (2009): 897-920. [11] Sukkoo Kim, "Immigration, Industrial Revolution and Urban Growth in the United States, 1820-1920: Factor Endowments, Technology, and Geography," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 12900 (2007). [12] Lee, Suzy, “The Case for Open Borders.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no4/the-case-for-open-borders. [13] Ibid. [14] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [15] Learning, Lumen. “US History II (OS Collection).” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ushistory2os2xmaster/chapter/the-impact-of-expansion-on-chinese-immigrants-and-hispanic-citizens/. [16] “Foreign Miner's License · HERB: Resources for Teachers.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1714. [17] Rana, Aziz, "Settlers and Immigrants in the Formation of American Law" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1075. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1075 [18] An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to the Chinese, May 6, 1882; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1996; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives. [19] Chin, Gabriel J. “The Great Dissenter Had Limits,” October 23, 2018. https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1996-05-12-1996133020-story.html. [20] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [21] Heer, Jeet. “Operation Wetback Revisited,” April 25, 2016. https://newrepublic.com/article/132988/operation-wetback-revisited. [22] Kitty Calavita, Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S. [23] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [24]Wise, Raul Delgado, and Humberto Marquez Covarrubias. “Strategic Dimensions of Neoliberal Globalization: The Exporting of Labor Force and Unequal Exchange.” Advances in Applied Sociology 02, no. 02 (2012): 127–34. https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.22017. [25] Loren Balhorn Oliver Nachtwey, Loren Balhorn, Oliver Nachtwey, Editors, Nicole Aschoff, Faris Giacaman, Daniel Kinderman, Umair Javed, Loren Balhorn Oliver Nachtwey, and Suzy Lee. “Berlin Is Not (Yet) Weimar.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no4/berlin-is-not-yet-weimar. [26] Kalleberg, Arne. “The Social Contract in an Era of Precarious Work,” 2012. https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/media/_media/pdf/pathways/fall_2012/Pathways_Fall_2012%20_Kalleberg.pdf. [27] Ibid [28] Ibid [29] Lee, Suzy, “The Case for Open Borders.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no4/the-case-for-open-borders. [30] “Farm Labor.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed