|

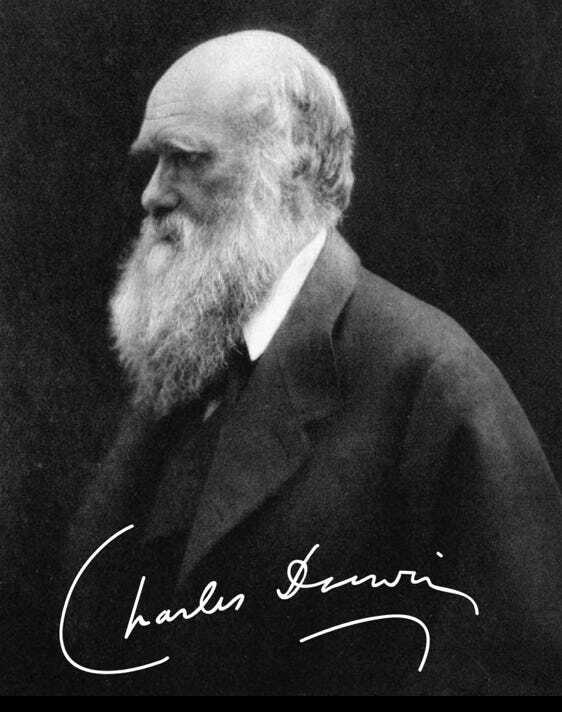

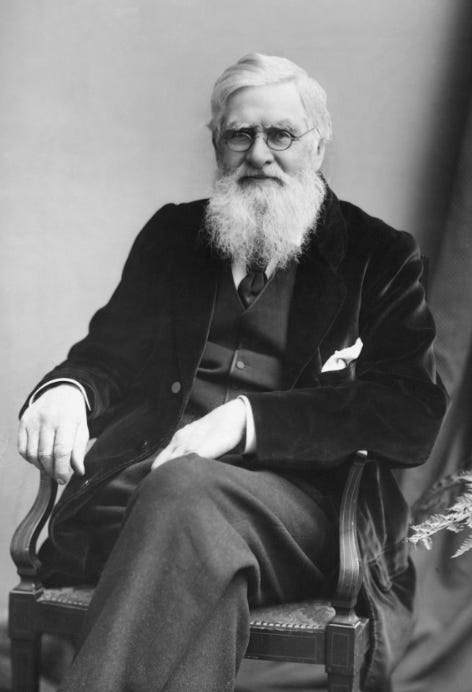

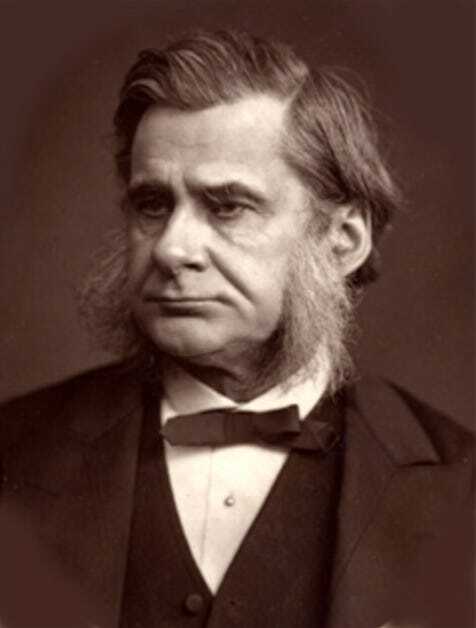

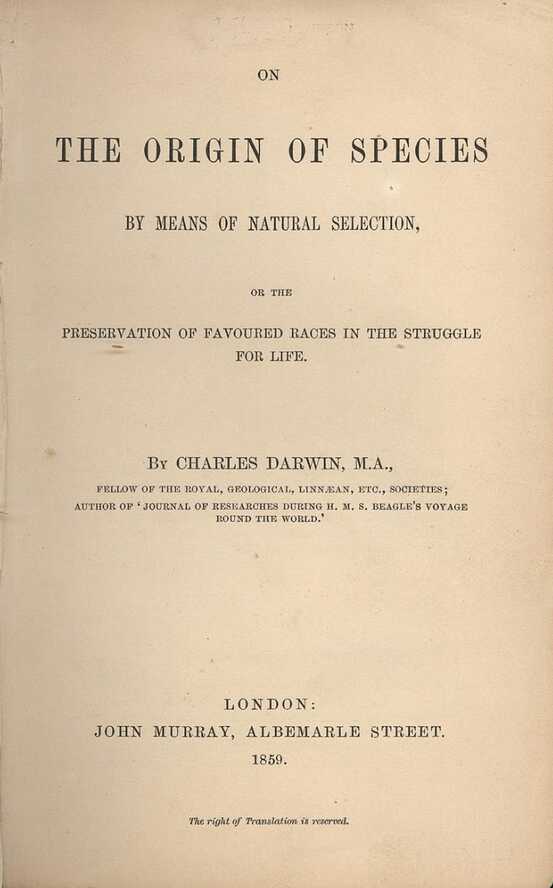

2/28/2024 "An accursed evil": Darwin's Struggle to Write "On the Origin of Species". By: JEFFREY S. KAYERead NowToday is Charles Darwin’s 215th birthday. On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, when Darwin was 50 years old. After a period of extraordinary scientific creativity in his late 20s, after returning to London from the five-year circumnavigation of the HMS Beagle, a period that included his working out of the theory of evolution via natural selection, Darwin did not publish on the subject of evolution for the next 19 years. Why? There are a lot of reasons. As part of my dissertation research into Darwin’s life, I looked at that question as well. As a treat for my readers (I hope it’s seen that way), I’m resurrecting a selection of that old work of mine (written in the mid-1990s, with only a few editorial changes). Hopefully, readers will tolerate, if not enjoy, this deviation from the usual fare on this blog. I had often thought of publishing this work, but the vicissitudes of establishing myself as a psychologist, raising a family, and other matters, pushed the Darwin work off my personal agenda. I’m posting a portion here, partly as a tribute to Darwin on his birthday, but also because I think it speaks to the difficulties adherent to living out one’s personal dreams in a complex world, considering the sociological, economic, cultural, and personal pressures that steer our lives, often in ways that we don’t always understand. As the selection below begins, Darwin has completed his years’ long task of studying and classifying barnacles. He undertook the work because he sorely felt his lack of credentials in biology. The lack of such professional recognition meant, he felt, that his work on biological evolution would never be accepted by the academic elite and scientists. Once he completed the barnacles job, the question of publishing his evolutionary ideas rose before him again…. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ In November 1854, Darwin accepted a prestigious position on the council of the Royal Society, and then, later that winter, moved the entire family to London for a month. The visit was practically a debacle. His children became terribly ill, and a close scientific acquaintance, the kind of younger scientist Darwin thought would be a supporter whenever he finally published on evolution, suddenly died at age 39. Still, Darwin’s presence at the Royal Society represented his commitment to take more interest in and remain close to London scientific circles. He spent his 46th birthday at a rare party given by Lyell's brother-in-law, Leonard Horner. Charles Lyell was the most famous geologist in the world at that point, and had been a mentor and supporter of Darwin’s scientific career. While he suspected Darwin’s “transmutationist” heresies, he overlooked them and in many ways, Darwin had been seen up to this point as one of Lyell’s more prominent disciples. Shortly after his return to Down from London, Charles began two projects directly related to his studies on the proof of organic evolution. He began keeping pigeons, in order to study the heritability of their physical and behavioral variations. He also initiated a study of seed dispersal, as he was troubled with problems concerning the geographical distribution of plant life, an important topic in his analysis of how evolution via natural selection occurred. The seed project soon began to overwhelm him with its difficulties, and he feared a repetition of the barnacle job, in that it threatened to become a years long research project in and of itself. Such a project would swallow up most of Darwin's time, leaving him farther than ever from the completion of his chosen life's work, the scientific proof of evolution by natural selection. This is not what he wanted at this point in his career. Even more disturbing, the complexity of the data Darwin was collecting and analyzing for a future work on evolution began to overwhelm him. In March 1855, Darwin told his cousin William Darwin Fox that he doubted "whether the subject will not quite overpower me" (Burkhardt & Smith, 1989, v. 5, p. 294).[1] When, later that same spring, the seed experiments began to go awry, Darwin complained to Hooker, "All nature is perverse.... I am getting out of my depth" (p. 326). Even a year later, in March 1856, shortly after Charles turned 47, he confided again to Fox that he still feared a breakdown, "for my subject gets bigger & bigger with each months work" (Burkhardt & Smith, 1990, v. 6, p. 58). A sense that time was growing short loomed over the entire project. Darwin was very self-conscious about growing older, and despite all his work, he still did not feel ready to begin writing his hoped-for book on species. The rear of Down House in the Kent countryside, the home of Charles Darwin over the last forty years of his life. (Photo: English Heritage) During these years Darwin remained decisively committed to the importance of family. The children at home were intimately informed about the progress of their father's research. He was most happy when all the children were at home, even as he feared for their future in an "old burthened country, with every soul struggling for existence" (Burkhardt & Smith, 1990, v. 6, p. 55). By the time Darwin was 47, having had seven children, with two others lost in infancy and childhood, he said about his children that "one gets, as one grows older, to care more for them than for anything in the world" (p. 56). And, as if to highlight the sentiment, Emma became pregnant again that very year, although this was almost certainly an unplanned pregnancy. The early years of Darwin's middle age were marked by a widening circle of social and scientific acquaintances. He joined the upper-class pigeon-breeders' Philoperiston Club only weeks before his 47th birthday. There were also new responsibilities shouldered, whether it was as treasurer to the Down Coal and Clothing Club, or as reviewer of papers for the council of the Royal Society. The extent of Darwin's activities at this time belies his image as an invalided recluse for all the years he lived at Down. Besides his English associates, Darwin initiated contact at this time with naturalists and scientists all around the world. One of the naturalists with whom he corresponded was Alfred Russel Wallace, then doing field work in Borneo. Wallace's solution to the problem of species' geographical distribution would entail an independent discovery of the mechanism of natural selection. This discovery would exacerbate both developmental and internal conflicts Darwin was having during the early years of his middle age, a struggle that centered around what to do about publishing his theories. Alfred Russel Wallace, from London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company (active 1855-1922) - First published in Borderland Magazine, April 1896 (Source: Wikipedia, public domain) Even as he turned 47 years old, Darwin remained content to gather more data in order to refine his theory of evolution. He did not feel ready to go public with his ideas. He did inform a larger group of acquaintances privately about his project — and received largely censure in reply — but he did not consider setting his findings down on paper until Charles Lyell decisively intervened. Lyell was a famous geologist and proponent of scientific uniformitarianism, the idea that natural processes that can be observed now have always (or nearly always) been in effect. Lyell had also taken on the role of Darwin’s mentor in the years after Charles’s return from the long Beagle voyage. When Lyell visited Down in mid-April 1856, Darwin finally explained to his mentor his full theory of natural selection. — Imagine! He had kept the theory a secret for approximately twenty years from the man who most supported him in scientific circles! — Lyell was aware that Wallace, at least, was working on similar problems, and seemed to be concerned about establishing scientific priority for his disciple's views. He also thought that with Darwin's theories published, he could critique them in a future edition of his major work, Principles of Geology, and therefore possibly be able to control the debate over evolution. In the end, Darwin could not abide by Lyell's suggestion for a quick essay or pamphlet on natural selection. His ambition, as well as his sense of scientific integrity, chafed against the format of a simple sketch. After a few months, Darwin had decided, in the middle of his 47th year, to write the full book he had envisioned. It was a momentous moment for him, for he had to accept the role of an iconoclastic innovator. The planned multi-volume work was to be titled “Natural Selection.” On one hand, Darwin seemed fully confident in the future success of his ideas, and the certainty that they would revolutionize natural science. But on the other hand, he still felt keenly his own scientific isolation, in addition to a lingering sense of dilettantism. "I shall have little sympathy from those, whose sympathy alone I value," Charles complained (Burkhardt & Smith, 1990, v. 6, p. 236). Both his emotional and physical health fluctuated. With Emma suffering through a difficult pregnancy, Charles leaned even more for support upon his friend at Kew Gardens, Joseph Hooker. As Darwin went over his materials once again, following an outline not too different from that envisioned in his initial 1842 and 1844 private sketches of the subject, he made subtle but important changes in his theory. There was a new emphasis on inherent variability, on the relativity of good-enough adaptation, and the addition of a principle of divergence as a corollary to natural selection. Meanwhile, Darwin struggled with the meaning of what he was about to do. He agonized over his own quest for fame, as well as his continuing fear that writing the book would be too much for him. He also had qualms over the amount of time and energy the project required. Months after Wallace's theory was announced, necessitating a switch in strategy from a very large multi-volume compendium on the subject of evolution and natural selection to the writing of a shorter book-length abstract, Darwin, then aged 49, told Hooker, "It is an accursed evil to a man to become so absorbed in any subject as I am in mine" (Burkhardt & Smith, 1990, v. 6, p. 174). Even as Charles turned 48, Emma was arguing with her husband that he was so overwrought he should return to Malvern’s spa for a dose of water treatment. But Charles was reluctant. He worked persistently at his manuscript. He travelled to London to further the career of his young protégé, John Lubbock. When he did finally return to hydropathy for relief, in April 1857, it was at Moor Park, not Malvern. Moor Park was much closer to home than Malvern was. After a week, Darwin was feeling better. “I can walk & eat like a hearty Christian,” he wrote to Hooker, “& even my nights are good…. I have not thought about a single species of any kind, since leaving home” (p. 377). But back home in May, he was already sick again, telling Hooker, “I fear that my head will stand no thought, but I would sooner be the wretched contemptible invalid, which I am, than live the life of an idle squire” (p. 403). Distracted also from scientific work by concern for his children's health — there was a diphtheria outbreak in the neighborhood — and by disputes among his friends, at times Darwin wished he could sunder all relations, all affections. "A scientific man ought to have... a mere heart of stone," Charles told his scientific correspondent Thomas Huxley later that summer (Burkhardt & Smith, 1990, v. 6, p. 427). By autumn, he told his cousin Fox, "A man ought to be a bachelor, & care for no human being to be happy!" (p. 476). Charles remained especially dependent upon Emma's care and love. A few months after he turned 49, Darwin offered to take over the care of the children in order that Emma might have a rest. Darwin continued to work away at what he felt would be a gigantic magnum opus on evolution. Scientific problems kept arising. He worked obsessively, such that his frequent correspondent, his cousin Fox, remonstrated him for his perpetual overwork. Meanwhile, Darwin had tentatively sent a chapter of his work to his botanist friend, Hooker. He was immensely pleased when Hooker, who was still averse to accepting evolution as a theory, much less natural selection, told Darwin his new work was scientifically formidable. Darwin wrote to Hooker: “You would laugh, if you could know how much your note pleased me. I had firmest conviction that you would say all my M.S. was bosh, & thank God you are one of the few men who dare speak truth. Though I shd. not have cared much about throwing away what you have seen, yet I have been forced to confess to myself… if you condemned that you wd. condemn all — my life’s work — & that I confess made me a little low — but I cd. have borne it, for I have the conviction that I have honestly done my best.” (Burkhardt & Smith, 1991, v. 7, p. 102). On June 18, 1858, Darwin received an extraordinary package in the mail. It was a letter and a manuscript from Alfred Russel Wallace. The manuscript was entitled, “On the tendency of varieties to depart indefinitely from the original type.” Darwin read it and dashed off a note to Lyell. He told him to read Wallace’s manuscript, and added: “Your words have come true with a vengeance that I shd. be forestalled… if Wallace had my M.S. sketch written out in 1842 he could not have made a better short abstract! Even his terms now stand as Heads of my Chapters. “I shall at once write [Wallace] & offer to send to any Journal. So all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed. Though my Book, if it will ever have a value, will not be deteriorated; as all the labour consists in the application of the theory.” (p. 107) In one of the great coincidences in the history of science, Wallace had worked out the concept of natural selection in the jungles of the Malay Archipelago just as Darwin was preparing his long book on the subject. The crisis then precipitated by Darwin's loss of scientific priority found its solution via the intervention of Lyell and Hooker, who saw to it that both Darwin and Wallace’s essays were jointly published in a scientific journal. But, crucially, Wallace’s paper forced Darwin to reassess the value of his work, and he decided its importance was not diminished by Wallace's discovery. Charles understood that the significance of his own contribution lay in the multifaceted discussion of the theory's application. When the joint Wallace-Darwin papers were presented at the Linnean Society, their effect was minuscule; Darwin had reckoned correctly. Through mature reflection, he knew that the theory had to be demonstrated, not merely asserted. Perhaps Charles could suffer the difficult loss of priority, the loss of a portion of his dream, because he was then also recovering from the very recent death of his youngest son. His daughter, Henrietta, too had just caught diphtheria. Most importantly for Darwin, the crisis over the Wallace events proved that, as he was about to enter upon a new and ominous period of his middle age, he could count upon the love of his wife, the friendship of Joseph Hooker, and the cautious backing of his mentor, Lyell. Perhaps this is why his double loss — of scientific priority and of his youngest son — did not destroy him. Darwin's perseverance against tremendous pressures, illness, and catastrophic loss, is not easy to analyze. Darwin himself thought that energy of mind, steadiness, and ability to sustain rigorous and long-continued work were his peculiar strengths. It appears to me that Darwin was able to contend with much strife due to the stability of the life structure he constructed during his 30s and 40s. In this, Darwin may have been very prescient in choosing a wife who could provide immense emotional support over the years (even though she was quite religious and Charles was not). Cropped and rotated version of Image:Origin of Species.jpg, which is off the title page and the facing page of the 1859 Murray edition of the Origin of species by Charles Darwin. (Via Wikipedia) Within a month of the Wallace events, though feeling old and weak, Darwin began preparing an abstract of his earlier, larger planned book. He entitled the new manuscript “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life.” In his later book, The Descent of Man, Darwin would make quite clear that all the races of men were of one species, a topic that was then still considered unsettled. While Darwin found value in the work he did, he still feared few would recognize its importance. With the publication of Origin of Species in Darwin's 50th year, Charles achieved, seemingly in one leap, a preeminent position in the scientific world. Yet his accomplishment was the result of long-prepared, gradual development during the years of early adulthood, mid-life transition, and initial middle age. Furthermore, the composition of the book was difficult, and Darwin more than once sought rest and hydropathic treatment at Moor Park spa. Darwin believed that he worked from an instinct for truth, but the pursuit of his dream of scientific accomplishment almost overwhelmed him. Even as he was finishing Origin, Charles fretted that his entire life's work had been for nought. At an extreme, he thought he might be insane. More than once, he told his friends how he longed to finish his "accursed" book, after which he could be "free" (see Burkhardt & Smith, 1991, v. 7, pp. 247, 270, 326, 328). He felt in his 50th year that, with the publication of Origin, his career had come to an end. The book had "half killed" him (p. 350). Yet, at other times, Charles also called his book "my child" and felt "infinitely pleased and proud" of it (p. 365). Lyell was helpful once again, this time in procuring a publisher. But Darwin realized very well that his book would be "one long argument" against anti-evolution theorists such as Lyell himself (Burkhardt & Smith, 1991, v. 7, p. 278). Accordingly, Darwin fervently hoped that his former mentor would be converted to evolution and natural selection. "Remember that your verdict will probably have more influence than my Book," Charles told him (p. 329). Darwin, uncertain of surviving a perilous future in scientific circles, and unwilling, perhaps, to surpass Lyell's accomplishments, fervently wished that the latter would accept evolution. Darwin knew that with the publication of his book, he was abandoning his former teachers and many naturalist friends. Neither was he sanguine about the response of his early mentor John Henslow, botany professor at Cambridge, to transmutationist heresy. Charles was resigned to Henslow's disapprobation. (Henslow died in 1861, and never was a major critic of Darwin’s work on evolution.) Darwin was barely ready to shoulder the responsibilities which his lonely scientific opposition would incur. Retreating to yet another water cure in Ilkley, he was joined by Emma and the children. Meanwhile, Charles was very dependent upon the approval and support of Hooker, Lyell (up to a point), and, increasingly, the young scientist Thomas Huxley. But it was Lyell who mattered most to Darwin, and the latter alternately argued and pleaded with the old geologist to accept the theories propounded in Origin. In the midst of this crisis, Darwin kept injuring himself repeatedly, hurting his ankle, his writing hand, and suffering repeated outbreaks of boils and rashes. As for Lyell, he never was able to “go all the way” with evolutionary theory in general, or natural selection in particular. The disappointment Darwin felt on this score led to a partial estrangement in his relationship with his former mentor, and increased Darwin’s sense of embattlement in the first years after the publication of Origin. When the full critical assault against Darwin's theory got underway, Origin had been in the bookstalls almost a year. Charles was turning 51 years old, and confused about what to do with the rest of his life. He was reticent about engaging with polemics with his scientific opponents. When Huxley offered to undertake the defense of Origin in the pages of various magazines and journals, Darwin was very grateful. He even egged Huxley on, especially as they shared an opponent in the powerful superintendent of Natural History at the British Museum, Richard Owen. In the scientific conflict with the powerful Owen, Darwin found access to his anger and aggression. He learned how to hate. It helped that he could hate, because he suffered from self-loathing. Over and over in his letters, Charles describes himself as "odious" or "arrogant" or "egotistical" (Burkhardt & Smith, 1991, v. 7, pp. 409, 457; v. 8, p. 141). In Owen, Darwin may have found a shadow figure. He often criticized aspects of Owen's personality that he found egregious in himself. For instance, Charles castigated Owen for his obsequiousness before the aristocracy, and for his slavishness to the court of public opinion. While these are not manifest traits in Darwin's own personality, he struggled through much of his adult life around issues of satisfying his social superiors, and was especially sensitive to public opinion. We can infer that what Darwin found so awful about Owen — the latter's propensity to bend his scientific integrity to the dictates of social approval — was an internal struggle within Darwin's character as well. When Darwin's theory began to divide the scientific world into warring camps, he suffered greatly for the destructive forces he believed he had unleashed. When, a few years later, the disputes degenerated into personal attacks over plagiarism among even his closest friends, the inner conflict Darwin suffered paralyzed him. But as he turned 51, Charles felt supported enough by Lyell, Hooker, Huxley and a few others, that he was willing to undertake a campaign for the support of his ideas. He was also trying to find a way he might continue his scientific work. On one hand, Darwin wished to finish the mammoth task of documenting the facts that had been presented in Origin as only an abstract of a treatise. This would mean many years spent on a multi-volume book, essentially a rewrite of the earlier omnibus manuscript, Natural Selection. On the other hand, Charles wanted to make new discoveries, and to remain a natural scientist. His work on the book which would become Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication, the companion volumes to Origin, was stalled again and again, as Charles found himself incapable of applying himself to the task. Instead, he looked to new objects of study — orchids, insectivorous plants, and the sexuality of flowers — in order to find suitable projects with which to apply his dream of scientific discovery. Footnotes [1] The references to Burkhardt & Smith in this post are to various volumes of The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, published by Cambridge University Press (1985-2023), which were edited by Frederick Burkhardt and Sydney Smith. At the time I wrote this material, this was the most comprehensive, scholarly, and accessible reference available for Darwin’s letters. Today, all the letters are online and accessible at Cambridge University’s fantastic resource, the Darwin Correspondence Project. The final volume of the printed work, number 30, was published last year. Hence all the quotes I use from Burkhardt & Smith in this article can be found at the DCP. (Later editions of the Correspondence sometimes had different editors.) Author: Jeff Kaye is a retired clinical psychologist. He's been researching and writing on US war crimes for over 15 years, and is the author of "Cover-up at Guantanamo: The NCIS Investigation Into the Suicides of Mohammed Al Hanashi and Abdul Rahman Al Amri." Currently he writes the blog "Hidden Histories" at Substack.com. Republished from 'Hidden Histories' Substack Archives February 2024

0 Comments

Attention all Marxists! If you thought class struggle was the motive force of history, as certain manifesto writers have claimed, you are sadly mistaken. As a book by Daniel Lord Smail, On Deep History and the Brain, has come up with the true motive force. This book is reviewed by Steven Mithen ("When We Were Nicer," London Review of Books, and he informs us that Smail says the motive force of history is "the manipulation of human chemistry by the substances we consume" willingly or unwillingly. Smail's thesis is that our actions are based on the long ago evolutionary development of our neurochemistry. Smail also reverses the biology/culture relationship that holds that culture is derivative from biology. At least this is what Mithen says. We will see that this is not the case since it is going to be neurochemistry (biology) which shapes culture and history. History doesn't really begin at Sumer. It begins way back in the Old Stone Age (the Paleolithic) when the major neurochemical agents influencing our brain evolved. Many of these Paleolithic chemicals are still at work today. Smail says: "What passes for progress in human civilisation is often nothing more than new developments in the art of changing body chemistry." Mithen tells us this is not just a rehash of the "crude evolutionary psychology" of Steven Pinker, Leda Cosmides, John Tooby and others, but is a "far more sophisticated" theory. We shall see. Smail says human history begins way before the advent of writing five thousand years ago and the view that there was an "unchanging prehistoric past" and then "history" is wrong. Mithen, who is an archaeologist, is in tune with this view. So, apparently, is everybody else these days. This is a terminological problem (or non problem). Marxists use the term "history" to refer to the advent of class society basically about five thousand or so years ago in the Middle East and "gentile" or "clan" society for the non class societies of "prehistoric" times. They do not believe that prehistoric societies (and what is "historic" and "prehistoric" varies in different parts of the world) were "unchanging." Rather they were dynamic and rapidly evolving, or stagnant, depending on the physical environments they found themselves in and that they had to adapt to to survive. Homo sapiens arose from Homo erectus about 200,000 years ago and Mithen thinks, as do many archaeologists, that there was a radical break in human prehistory about 70,000 years ago "when the first unambiguously symbolic artifacts and body adornments are known" (Blombos Cave, South Africa). Right after this time H. sapiens began to spread out of Africa into the rest of the world. Mithen thinks that this has something to do with the final evolution of language. He also thinks, because of the "radical break" Smail may be wrong to deny some period of historylessness to the period prior to 200,000 years ago. Mithen says, "'the myth of Paleolithic stasis' may, in fact, be the reality prior to Homo sapiens." By the tenor of his own argument, it might be the reality prior to the "radical break" as well. Using the word "history" in a greatly expanded, and I think unhelpful manner, he says that Smail is right about "history" itself going farther back than H. sapiens. Mithin agrees that even chimpanzees and baboons "have history." This is because their current social reality is based on their past social reality. So almost everything is historical. Why stop at baboons? Why not include the birds and the bees? It is far more useful to apply the term "history" to the written or remembered record and keep the term "prehistory" for the deep past. If your group has no consciousness of "history", you probably don't have a history to be conscious of. New problems spring up when we leave the Old Stone Age for the New-- for the period called by Vere Gordon Childe (1892-1957) the great Marxist archaeologist of the first half of the 20th century, the time of the Neolithic Revolution. This is the period of about 8000 to 3000 B.C. (at least for Europe and its immediate neighbors). The previous mode of production had been hunting and gathering. Now we settled down to farming and soon to building towns and cities, classes, and the first state structures. So, I think, history does begin at Sumer after all. This doesn't mean prehistory is a blank. Childe calls the Neolithic a Revolution because, as a good Marxist, he saw the new mode of production, large scale agriculture, as a qualitative leap and change from the hunting and gathering of the past. This was due, as Mithen points out, to H. sapiens reaction "to the start of the Holocene some 11,600 years ago, with its warmer and wetter climate than the preceding Pleistocene." Smail calls this period "the fulcrum of the great transformation" of human history. This is exactly what Childe thought as well. Now we come to Smails' special theory. As a result of the Neolithic's new living conditions-- some humans began to settle down and give up the hunting gathering lifestyle. At this time, says Mithin, Smail says "our Paleolithic-evolved neurophysiology" begins to assert itself. The primate social structure, as seen in chimpanzees and baboons and based on domination "often" brought about by "random acts of violence" to keep lower ranking members of the group fearful and stressed out, begins to reappear. This argument does not seem to hold water. Mithen points out most hunter gathers have egalitarian societies. He says the evidence is that the "majority of Paleolithic hunter-gathers were egalitarian" as suggested, by the way, by Engels in his discussion of primitive communism in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. So the neurophysiology that we evolved in the Paleolithic would not have resembled the chimp-baboon model necessary for Smails' theory. Mithen, however, finds some of this new theory fairly persuasive. Smail says the new political elites that developed to control trade and agriculture "needed to control the brains and bodies of their subordinates by manipulating their neuro-chemistry." So they ruled by relying on "random acts of violence" against their people to keep them down through fear and stress, via the head baboon, since "control of agricultural surpluses or trade routes was not enough to maintain their power base." This is just completely unscientific speculation worthy of a vision of the Neolithic conjured up out of reading too many Edgar Rice Burroughs novels. Of course, Smail holds that the rulers were not aware of what they were doing-- Mithin says, "they were simply repeating what had seemed to work in gaining them power. Random violence is a winner every time." There is no evidence that the political elite in the Neolithic period used random violence against their people to maintain power. This is just speculation and guess work. Mithin however says that it wasn't just physical violence. People who know about the Neolithic site of Chatalhoyuk (Anatolia: 7000 BC) will find Smail's views "particularly striking and persuasive." Why is this? Because, at this site "we find horrendous wall paintings and sculptures showing decapitated people and monstrous animals." This is very emotive. Let’s give a more scientific formulation. Here "we find strange (to us) wall paintings and sculptures showing headless people and large unknown mythological animals. We do not know what the purpose of these images was. Perhaps it was religious." This is not the conclusion of Mithin. He simply asserts that these images show "a culture of suppression through terror, with-- no doubt-- a priestly caste benefiting from these visions of a Neolithic hell." Terror was used to "attack the body chemistry" of the people (evolved during the baboon Reign of Terror) to make them fearful and afraid of those "intent on maintaining power." These speculations are completely without merit. From the Neolithic we advance into the historical period proper. Since our neural states "are plastic and thus manipulable" we find that "new forms of economic, political and social behaviour emerge during the course of history." The six most important vis a vis our neurochemistry have become also the most important for human culture. The six are "religion, sport, monumental architecture, alcohol, legitimised violence-- and sex for fun." At least random violence is not on the list. These six are the "most effective in moulding and manipulating our body chemistry." So the Romans had it down with bread and circuses. First put the subject population under stress, then provide relief which advantages the ruling class. "What better way," Mithen notes, "for elites to build and maintain their power than to create stress within a population by a culture of terror and then very kindly to offer the means for its alleviation by arranging such events." Examples today would be professional sports, movies, and especially great events such as the Olympics. Mithin quotes Etienne de la Boetie (1530-1563) who in 1548 referred to sporting and theatrical extravaganzas as "tools of tyranny" and "drugs for the people." Methods used by others to influence or control our brain and body chemistry Smail calls "teletropic mechanisms." Those we use on ourselves are "autotropic." Mithin points out that it "is far better for those in power to be in control of their subordinates' body chemistry than to leave it to the subordinates themselves." This is why many religions, for example, as ruling class tools, reject such autotropic mechanisms as masturbation, sex for fun, alcohol, and recreational drugs. The state, in fact, seeks to regulate and control autotropic mechanisms as far as possible. The plot thickens. The world historical change from the Middle Ages to our modern world may be better explained by the manipulation of neurochemistry than by Marxist theory. The European discovery and use of tea, chocolate, coffee, and tobacco allowed people to regulate their own brain chemistry, for these items are all autotropic. The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of the struggle between autotropic and teletropic mechanisms. Smail is credited with Mithin's comment that the "Making of the Paleolithic relevant to the drinking of tea is no mean feat." Two quotes from On Deep History and the Brain sum up the argument and bring us to the book's grand conclusion. "We can finally dispense with the idea, once favored by some historians, that biology gave way to culture with the advent of civilisation. This has it all backward. Civilisation did not bring an end to biology. Civilisation enabled important aspects of human biology, and the drama of the past five thousand years lies in the fact that it did so in ways that were largely unanticipated in the Paleolithic era." The second quote is "we need not dig only in the dusty topsoil of the strata that form the history of humanity. The deep past is also our present and future." What Marxist would disagree with this first comment. It only says that human potential has been increased by the inventions of civilization and that these inventions were not foreseen in the Old Stone Age. What Smail means is that the brain chemistry that evolved in the Old Stone Age was not adapted for the changes that lay ahead, it being oriented towards the teletropic. But we have already seen that H. sapiens in the Paleolithic was largely egalitarian (primitively communistic) and so autotropic. The evolution of our brain chemistry fits into any type of society it would seem. As for the notion of the "deep past": it is of course true that we are the product of evolution, of animal ancestors and that this heritage remains with us today and forms part of our nature. Who, since Darwin, would deny that? The question remains, how are we best to understand history, the rise of capitalism, the contradictions of imperialism and the way to overcome them and proceed on the road to socialism? Historical Materialism, the theories of Marx, Engels and Lenin are still to my mind the best methods to use to answer these questions. It is true that candy is dandy, and that chocolate, masturbation, and alcohol are handy autotropic devices, but they won't replace class struggle and the analysis of the means and modes of production as ways to change the world. Political power does not grow out of a Hershey bar. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives February 2022

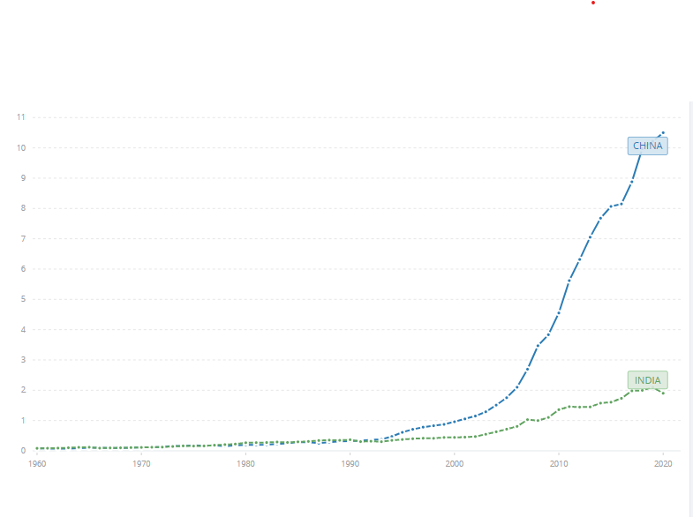

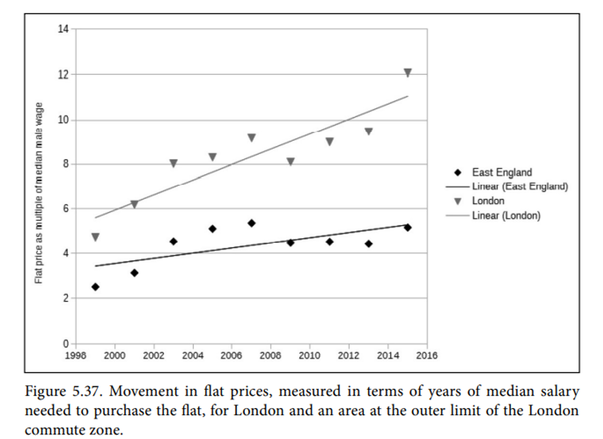

There is so much confusion these days. We are coming out of an era of confusion, of purposeful distortion, of the establishment and arms of the state using its sophisticated propaganda machine to mislead us in so many ways as to what our interests are, that even once we begin understanding that it is the system itself that is the problem, we are immediately confronted with more distortions designed to redirect any potential revolutionary energy away from ever being a threat to the ruling class. This includes confusing us over what basic terminology is. Recently, I’ve been clarifying old Marxist terms that have been distorted over the years on social media (search for the hashtag #MarxistTerminology if you’re interested!). And this phenomenon is why I wrote this essay. I mean, even the word Marxism is a mystery these days. So let’s begin very simply: Marxism is a science. That’s right. You read that correctly. The words haven’t melted into each other, and you aren’t having an aneurysm. Marxism is a science. Or, more precisely, Marxism is a social science. Or, even more precisely, Marxism is THE social science, the science that shows how unscientific liberal social sciences are, by genuinely explaining how things happen in society and why. But how can this be, I hear you ask from across time and space. It seems so weird. Marxism can’t be a science. Science is when nerdy looking people in lab coats and goggles do experiments with test tubes, and then smoke comes out of the test tubes. And sometimes, when it’s really funny science, the science will blow up in their face and it’ll be all singed for a minute before it goes back to normal. Or, if it’s a duck doing the science, maybe his bill will get turned around. That’s science, right? And that’s certainly not what Marxism is. Well, no. Just… just no. All science developed through analyzing what is, thinking about the world around us, and creating and adding to bodies of knowledge that can explain the operation of general laws. And, boy howdy. Marxism fits this description like a glove, despite all of the metrics various ideologically motivated intellectuals have come up with in order to try to dispel the notion. In fact, Marx himself viewed things this way. And it has only been added to and improved upon over time. Entire countries have been founded on the discoveries Marx made. And today, these discoveries are leading the world into a new era. So, what makes it a science, then? It’s all well and good to make declarations about what is and isn’t science, but if we don’t explain why, how this science developed, well—then, it just isn’t very helpful. We need to know what the component parts of Marxism are and how they came to be in order to judge for ourselves what, exactly, it is. We wouldn’t call something a cheeseburger if we didn’t first open up the bun and make sure the components of a cheeseburger (1 burger, check; 1 cheese, check) were there first, would we? So, let’s give the same courtesy to Marxism that we give our various lunch and barbecue foods. William Z Foster, founding member of the Communist Party USA and heroic labor leader of the early to mid-1900’s, wrote one of the best histories of Marxism and Marxists to date towards the end of his life, the “History of the Three Internationals”. In this seminal work, he opens by describing the history of the pre-Marxist labor movement, culminating in an essay that describes the real birth of socialism as we know it today, and what made Marxism so effective in the real world, so different from everything that came before it. Marxism is a large word, and it encompasses so much, but Foster identifies the eight core features of Marxism in his essay “Major Principles of Marxist Socialism”, taken from this section in one of the most concise essays on the topic to this very day. These core features of Marxism create a progressive increase in our body of knowledge on the study of society and its progress. You’ve probably guessed by now that we’re going to be detailing those eight features here, right? If so, give yourself a high-five. You nailed it. So, let’s get started, shall we? 1. Philosophical Materialism All science rests on the fundamental idea that the material world is primary, and that our ideas are a reflection of that objective reality. Materialism says that we do not pluck ideas out of the ether and shape the world as we see fit, operating on a proverbial blank slate, but instead, that the world shapes us, that our actions are based on the way we interpret this reality, and on what is possible within that reality. Karl Marx was the supreme philosopher of materialism in his day, the original taker of the red pill. He based himself fully in this understanding, and counter-posed it against what he considered the “idealist imaginings” of others, such as Hegel, Hume, Kant, and Berkeley, whose philosophical systems all led, though one route or another, to the acceptance of some type of world creation. For philosophical idealists, it is not the material world that is primary, but the idea. A great thinker or powerful leader would poof an idea out of the ether and then put this idea into practice. For Hegel, the entirety of world history was the formation of ultimate truth through the continual process of making more precise, the idea. Marx, instead, proposed a world ruled by definite laws, and showed us how understanding these laws would lead to a greater understanding of the world itself. Not only that, Marx also showed us, in his various works, how the idealist outlook on the world constitutes a shield for the capitalist class, and how materialism could be, as Foster called it, the “sharpest intellectual weapon of the proletariat in its fight against capitalism and for socialism”. 2. DialecticsDialectics is a scary-sounding word. Almost as scary as “Bigfoot”. But once we understand what it means, it turns out it isn’t that scary at all. Really, dialectics is the study of motion—the motion of all things and how that motion happens. Lenin once described it as, “the theory of evolution which is most comprehensive, rich in content, and profound”. But that’s a little jargony and dated. Let’s put it into ordinary human language (another great phrase from Lenin), so we can wrap our brains around it. What did Lenin mean when he said this? What is dialectics? What are the nuts and bolts? “Motion is the mode of existence of matter.” When we study the motion of something, the first thing we usually want to understand is what causes that motion, right? If we want to know how a car moves, we need to understand that it has an engine and a gas pedal and all the other parts that work in interconnection that make it move. Dialectics is like learning how a car moves, but for the entire universe and everything in it. Every phenomenon has internal forces that produce its motion. When we “look under the hood”, so to speak, we discover that there are mutually interdependent forces that ‘struggle’ against each other inside any given phenomenon. The study of the molecules inside water that push against each other in order to create its evaporating or freezing point could be said to be a dialectical study of water. In this same manner, the study of the struggle between capitalists and workers is a dialectical study of society. Without dialectics, our materialist foundation is incomplete, since it is impossible to truly understand a phenomenon without understanding the core foundation of that phenomenon, its motion, the way it develops and deteriorates. The two form, one could say, an interdependent concept. Without understanding what’s under the surface, we have—well, only the surface. We can say that society is full of people who do work, but dialectics and materialism give us the tools that help us understand why those people do this work and why they do it the way they do. 3. The Materialist Conception of HistoryIt was Marx and Engels who first put the study of history on a scientific footing, tearing to shreds the old metaphysical and subjective ways of writing “history” in much the same manner as an electric shredder tears documents apart at the Citi-group offices. Through extensive, exhaustive, (and often exhausting) explanation, using their dialectical materialist methodology, Marx and Engels peel back coincidence, and trace all of the myriad phenomena in society to their source, to the one central root cause of why things in society happen the way they do. In Marxism, we often refer to this as the ‘economic factor’, or the way production is carried out within a given society. Or, simply, the way people make their living. Marx said on this, “In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material powers of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society—the real foundation on which rise legal and political superstructures to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political, and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness.” This neatly sums up one of the major discoveries of Marxism, the economic factor as the basis of the motion of society, which we commonly refer to as the base. This puts all the rest of it into motion, and builds what we call the superstructure upon it, our political systems, laws, spirituality, and everything else. Let’s break that open and make sure we’re all on the same page before we move on, though, shall we? Since it is precisely the opposite way to look at it from the one we are taught by default. What does it mean to say that people (Marx uses men, but this is 2022 here, okay?) enter into ‘definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will’? Well, people are forced to work with and create relationships with each other in order to engage in production, right? It really doesn’t matter what we want—what matters is that we are forced to do this in order to function in society. If you are a working class person, you must go out and sell your ability to perform work to someone who owns the property which makes production possible. If you’re a capitalist, you must buy that ability to perform work from workers. Without this relationship between worker and owner, capitalist production doesn’t happen. There are many levels of this, and sometimes these days, the capitalists themselves are mostly removed from the process, instead buying the labor power of some people in order to do that for them, but it still all boils down to this essential relationship. Okay. That was easy. How about the next part? These relationships correspond to a definite stage of development of their material powers of production. Don’t worry; this one’s easy too. In order to analyze society’s motion, Marxism breaks the progress of history up into stages (I like to picture it like a timeline in my head, and each part can be divided up into stages as we see fit, in order to more easily analyze the motion). Each of these stages was created by a great leap in the technology related to production and served to advance society. The advent of the slave societies (sometimes called Antiquity in bourgeois universities), which came after what we often refer to as “primitive communism” or pre-class society, for example, was based on the invention of agriculture. Planting crops and domesticating animals rather than hunting and gathering was a completely new way human beings were engaged in production, a new form of society. We, as a species needed to eat, and as we grew, needed to eat more and more. So, we hunted and gathered more and more, and in better and better, more efficient ways, making the production of that era more efficient. This created a surplus, and then a need to own our new surplus. Likewise, the invention of factory assembly, coal and steam power represented the beginning of capitalism. Each of these class relationships (master and slave in the early era of class society, owner and worker in capitalism) correspond to the level of technological development of the human race. All of that innovation based on what’s most economically efficient, that’s what comes first. It lays the basis from which everything else in society rises. The way we go about organizing our society, our legal and political structures, that all stems from how we look at the material conditions we find ourselves in. We don’t have class without some people owning and some people working, after all. Marx was pointing out the dialectical progression of phenomena in society, a heady concept for sure, but one we can break apart and learn, as we see here. He ends the statement with a very good, quotable line that really just sums it all up: The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political, and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness. Marx is saying that the form our society takes has a material basis in the economic factor. Back into ordinary human language, he’s explaining that the way we go about producing, the ‘mode of production’ and the objective relationships this causes is what determines what our social, political, and spiritual lives look like. It isn’t good ideas producing good things or bad ideas producing bad things. It is the material reality that produces good ideas and bad ideas (and even how we look at those ideas); the social relationships we create in order to, well—create, those come first. That affects how we think about things, and as we get more advanced, new ideas manifest. This quote has led a lot of people who don’t really take the time to understand what it means (a lot of them due to their class interests, as class is a large determining factor in the kind of social consciousness people have) to launch an accusation of “economic determinism” at Marx and Marxism, saying that Marxism states that only the economic factor is important, and dictates everything that happens, as if people don’t have free will or work against their own class interests. But this is a misunderstanding, and seems like it forgot to read the last part of Marx’s quote here. Engels addressed these detractors directly, saying, “According to the materialist conception of history, the determining element in history is ultimately the production and reproduction in real life. More than this neither Marx nor I have ever asserted. If therefore somebody twists this into the statement that the economic element is the only determining one, he transforms it into a meaningless, abstract and absurd phrase. The economic situation is the basis but the various factors of the superstructure – the political forms of the class struggles and its results – constitutions, etc., established by victorious classes after hard-won battles – legal forms, and even the reflexes of all these real struggles in the brain of the participants, political, jural, philosophical theories, religious conceptions and their further development into systematic dogmas – all these exercise an influence upon the course of historical struggles, and in many cases determine for the most part their form." What he means is that the source of what happens is the economic factor, but the things it creates, these matter too, and affect the course of historical events. For example: because race and racism were created to serve capital does not mean that racism itself has not played a large role in the development of American society, or that it is not a large part of the general class struggle in this society. When we engage with the study of history using Marxism, we see that the old, bourgeois way is simply not enough to genuinely understand the real cause of things. In fact, it tends to outright ignore the true cause of events throughout history, laying emphasis instead on all sorts of secondary or superficial elements, on great ideas of great men or evil ideas of evil men. Overall, a bourgeois history lesson is often a random jumbling together of dates and deeds, battles and warriors, with very little (if ever) talk on the root cause of these battles and warriors, on the economic factor pushing these forces into motion. It can often pretend at this but fail in every respect. Case in point: the reason often given for the beginning of the first great imperialist world war is the assassination of Arch-Duke Franz Ferdinand. This is all well and good. It was a very early battle in this war, possibly the first skirmish. But why did it happen? What were the underlying factors that caused this event? These are the questions Marxism answers. If bourgeois history has no real, clear understanding of the past, then how can they possibly understand what is happening in the present? Historical materialism, however (the term we give to the dialectical materialist methodology applied to history), and its emphasis on the economic factor, gives Marxism what Foster called a “decisive advantage in drawing the elementary lessons from past history, and for understanding the fundamental meaning of the complex economic and political processes of today.” It’s this study that leads Marxists to the conclusion that economic revolution (those leaps in technology we talked about) leads to social revolution (changing conditions create an inability to live in the old way, as well as new ideas), which leads to political organization and political revolution (people are thrust into motion to do what they must to continue society, and that is a complete transformation of the basic characteristics of society into a new form), which leads us to the conclusion that socialism, the stage of development after capitalism, is inevitable. This may sound very strange at first glance, but as we learn the scientific basis and understanding of this, it naturally becomes clearer and clearer, especially when we learn how this happens over and over again throughout history, in different forms corresponding to the material levels of production of society. 4. The Class StruggleMarx wrote in the Communist Manifesto: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes. In the earlier epochs of history, we find almost everywhere a complicated arrangement of society into various orders, a manifold gradation of social rank. In ancient Rome we have patricians, knights, plebians, slaves; in the middle ages, feudal lords, vassals, guild-masters, journeymen, apprentices, serfs; in almost all these classes, again, subordinate gradations. The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society has not done away with class antagonisms. It has but established new classes… new forms of struggle in place of the old ones." Marx’s description of this process, of class struggle, is a description of the processes happening throughout history, compelling the motion of society. He is applying the dialectical materialist methodology to society, putting the study of its motion, of the conflicting forces making history happen, onto a scientific footing. This helps us understand all of the internal laws of motion of society, but it is up to us to put them into practice. Without Marxism, this is a confusing jumble of events, but armed with our scientific method, we can understand the forces at work that produce different events throughout history. The economic factor, again, is the central root of everything. The direct relationships people must enter into in order for society to function separates us into mutually interdependent and contradictory classes. In order for one class to fulfill what is in its material interests, it needs to directly harm the material interests of the opposing class. If a corporation (a group of capitalists recognized by the state) decides to shut down its factories in one location and move them to another one where it is able to pay workers less, this directly harms the material interests of the workers there. Likewise, when a factory organizes into a union in order to win higher wages, this harms the material interests of the capitalists. Marxism gives us the tools we need to understand this on a systemic level, to understand what our material interests as a class are. We see the opposing class (what Marx called the ‘bourgeoisie’) everywhere trying to obscure this fact, to obscure class and blur even what the term means, which can easily result in us accidentally siding with its interests against our own. Marxism doesn’t just give us the tools we need to understand history properly, but also to fight against that obscuring, and to work towards what’s best for us, instead. Marx was incredibly modest about this significant scientific discovery. In a letter to American Marxist Joseph Weydemeyer in 1852, he said that he deserved no real credit for discovering the existence of classes in modern society, or even the struggle between the opposing classes. Bourgeois academics had already begun pecking around the edges of class and production before Marx began his work. He explained the important parts of his work as having three essential parts: First, that the existence of classes corresponds to particular, historic phases in the development of production; Second, that the class struggle necessarily leads to what he referred to as the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, or the working class organized as the ruling class of society, and its interests dictating what happens in society (according to the laws of societal development); And third, that this new form of state only constitutes the transition to the abolition of class itself, and to a classless society, as the material interests of the working class necessitate working towards the end of classes altogether. There are many labels given to this, and many misrepresentations of it, based on not quite understanding the way Marx and Engels thought, what it was they were doing. In our modern society, we refer to this period after capitalism as “socialism”. Through all of this, if we look at this the way Marx did, we see that he was studying society’s motion, its progress, and discovering the forces that made that progress happen: class struggle, the dialectical “struggle” between the two opposing and interdependent forces within the phenomenon of society. As Foster took care to note, Marx was being incredibly modest in this letter. Marx and Engels created a methodology that would let us clearly see not just what is here now, but how we got to here, and in so doing, gave us the guide we need to continue progressing society and fight for a better world for the working class, for the masses. For us. 5. The Revolutionary Role of the Working ClassThe word class has become rather murky in modern American society. What is a ‘class’? Our pundits and bourgeois academics talk of the “middle class” quite frequently, or of the ‘political class’ or ‘professional managerial class’. These can have some sort of merit in our Marxist analysis, but over-all, the establishment tells us to measure what we call ‘class’ in terms of income level. The more money one has, the higher their ‘class’. This is not the terminology Marx and Engels used, and not how Marxists view ‘class’, how we separate groups of people when analyzing society and its motion. We do this, like all things, by our dialectical materialist methodology. We get to the root of things, to the economic factor, and discover that the best way to group people is according to their material interests, which lies in the social relationships created by how they relate to production. It is that relationship to production that defines what ‘class’ a given group is in Marxism. (Once we learn the fundamentals, it’s important to recognize how the distortions of the capitalist class serve their class interests, by distorting how people view themselves and production itself, individualizing it. But that’s a subject for another time.) It’s common knowledge that Marxism focuses on the ‘working class’, a group of people whose relationship to the means of production, the way they go about living and being part of society, is their lack of ownership and ability to accumulate, forcing them to sell their capacity to perform labor (a special commodity Marx calls ‘labor power’) to those who own the means of production. But Marx and Engels did not study the working class arbitrarily, or because they suffered at the hands of the ruling class, or because they wanted everything to be fair for everyone and the working class were large and represented the masses. In fact, the peasantry was larger in many regions of the world in their day, and had a completely different relationship to the means of production, one left over from the feudal era, as capitalism was becoming the dominant force in society. It was their special position as the developing class of society and material interests as the working class that made Marx and Engels focus on this class. It was (and is, to this day) in the material interests of the working class to overcome class altogether, to create the productive forces and relationships of production necessary for class itself to no longer have a reason for existing. Every dollar the workers get, the bosses see that as a dollar they lose, after all. This constant back and forth struggle would best serve the working class by overcoming it altogether and eliminating the capitalist from the equation, while the bosses, on the other hand, rely on the working class to actually produce value for them. Other classes faded with the passage of history and the development of capitalism. In Marx’s day, the small shopkeepers, artisans, and small manufacturers all stood opposed to the bourgeoisie, but for a different reason than the working class. Their class interests were in preserving their positions, making them “conservative” in the true sense of the word[1], and as capitalism progressed, became reactionary, meaning their class interests were better served in the previous stages of society. The working class, however, is produced and grows according to capitalism’s advance, and is therefore the class in the position to be the “nascent” or developing end of the contradiction at the heart of society’s progress, the only truly revolutionary class of the period of history in which capitalism is the dominant stage of development. Due to its position and material interests (remember, the Marxist focus on the economic factor), the leading role of the working class, the constructive class to build our future, has been present in successful revolutions to get past capitalism all over the world, in Russia, China, Cuba, Vietnam, etc., and working classes all over the world take it upon themselves to organize and bring this about. Lenin elaborated on this phenomenon very thoroughly, but it was Karl Marx who first began laying the groundwork for this addition. In the Communist Manifesto, he wrote of the type of, as Foster called it, “thinking-fighting-disciplined party necessary for the working class to win finally over the capitalist class.” “The Communists… are on the one hand, practically, the most advanced and resolute section of the working class parties in every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement.” So what did he mean by this? At first glance, it sounds a little egotistical, but that is not the way Marx viewed the world. He saw this as a scientist, and in order to understand what he meant, so must we. Marxism shows us that the dominant ideology and way of viewing things in any society is the ideology its ruling class. That ruling class was able to spread this way of thinking throughout that society, but it is important to look at this fact dialectically, to analyze it in its motion. Because it is dominant now does not mean it is invincible but precisely the opposite. It means it has developed already and is now undeveloping. The time this takes to happen and the way it happens are governed by the phenomena mentioned above, by class struggle and its own development. 6. Surplus Value We often hear Karl Marx’s three volume work Capital referred to as his magnum opus. Before Marx, the great bourgeois economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo wrote on this period of history, and contributed greatly to our understanding of capitalism, value, and commodity production. They were operating in the time before Marxism, however, before the world outlook and methodology of Marxism was able to give greater clarity to the study of society and how it functions. These days, the bourgeois economists, in their increasing desperation to provide excuses, have degenerated into little more than con men, making apologies for capitalism, rather than genuinely examining its functions. Capital was Marx’s great work on this subject. Taking his new world outlook and methodology, he was able to describe the process of society and its motion, and specifically capitalist society, in a way never before possible. He explained the process of what led to capitalism, which he deemed primitive accumulation, the causes of the crises, panics, recessions, crashes, capitalism experiences every four to ten years like clockwork, and the continual concentration of capital in the hands of fewer and fewer capitalists. One of the greatest discoveries elaborated in this book was what Marx spent decades studying. What is value? Where does it originate? Marx’s elaboration of what he deemed ‘surplus value’ [2]– the value that capitalists derive from commodity sales that is not paid to the workers for their creation or used to maintain their means of production. This discovery exposed the capitalists for what they were: parasites, and this surplus value being the property of the capitalist class is the central element of the opposing interests between worker and owner, why the working class is the truly revolutionary class, according to Marxism. Since then, countless bourgeois academics have tried to refute Marx’s great work on this subject. None have succeeded. 7. The Role of the state: This is beginning to feel a little like a “Marx’s Greatest Hits” list, isn’t it? Coming in at number seven, it’s (drumroll) the role of the state! Give it a hand, everybody! Okay, bad jokes behind us. Let’s continue on. Marx and Engels dedicated quite a bit of study to the question of this thing called the state; what it is, how it developed, what its concrete manifestations are, things of that nature. While the bourgeois academics would hold that the phenomenon of the state developed spontaneously, due to the good ideas of good men (only men), and stood above society, concerning itself with the welfare of all of the people, Marx and Engels showed that The State, like all things, goes through a process of development and undevelopment due to the internal contradictions within it, based on the economic factor, that the state takes different forms according to which class is the dominant class in society, and is the tool of the dominant class of society for the repression of the other classes. They showed that, with the progress of the working class state, the continual advance of the productive forces, and motion of society, the state itself will eventually begin to wither away and un-develop, once the conditions for its existence (class struggle) are no longer a factor, replaced simply by the routine administration of things. 8. Class Struggle and Tactics of the Working Class:Marx and Engels did more than that, though. They also began understanding the forms of struggle and tactics the working class takes in its continual struggle against the bourgeoisie. William Z Foster details quite a lot of their correspondence and actions within the International Workingmen’s Association, or “First International” in his book History of the Three Internationals, which represented the first real organization of the working class in its own interests. (The letters between the two detail their original ideas on this issue, and are a fantastic read for Communist nerds, even to this day.) Before their work in showing the world the exploitative nature of capitalism or organizing workers themselves, they proved how the nascent class of society always organizes itself and overthrows the moribund class, showing how only the proletariat were in a position, once organized and educated, to lead the entire toiling masses towards socialism. They did not, however, sit around dreaming up ideas for ideal worlds, as the utopian socialists that came before them did. Instead, they relied on cold, hard science to guide the way, instead developing what is often referred to as a “guide to action”. Of the many distortions and misconceptions about Marxism going around today, the idea that this was what Marx and Engels did is one of the most prevalent. If life were a football game, this distortion would have us believe that Marx and Engels wrote out a playbook, and their criticism is that we cannot expect some playbook written for a football team 200 years ago to work on our team now, with totally different players, rules, and conditions (or sometimes, they argue that we should follow this imaginary playbook they believe was written). But Marx and Engels and company did not write a playbook for us. Of course, they were interested in a playbook for their specific team, and created this, but their main discovery was the creation of the language playbooks are written in. They developed all the X’s and O’s and little arrows you see in football movies, when the coach is explaining the trick play to the team that’s had a rough first half, so they can win the game at the very end. This language is the essence of Marxism. And each socialism that arises develops its own playbook from this language, and each socialist project wins the game with their own, unique plays, written specifically for their own conditions, their own unique time and place. Learning dialectical materialism and historical materialism, learning how to “think like a Marxist” and then apply that to our actions in the real world, is the first step in building socialism. [1] Conservative is another term that our capitalist class has mystified. Conservatism when reading Marxist texts essentially means exactly what it says on the box: to conserve what is. [2] This work will not delve into descriptions of economy in this way, and is mostly a primer. But for the sake of thoroughness, surplus value is described by Mehring as, “The mass of the workers consists of proletarians who are compelled to sell their labor-power as a commodity in order to exist, and secondly that this commodity, labor power, possesses such a high degree of productivity in our day that it is able to produce in a certain time a much greater product than is necessary for its maintenance in that time. These two purely economic facts, representing the result of objective historical development, cause the fruit of the labor-power of the proletarian to fall automatically into the lap of the capitalist and to accumulate with the continuance of the wage system, into ever-growing masses of capital. (Note: knowing the dialectial nature of society, we can look at the development of just HOW productive this commodity is, and how much more productive it is today than in Marx’s day) AuthorNoah Khrachvik is a proud working class member of the Communist Party USA. He is 40 years old, married to the most understanding and patient woman on planet Earth (who puts up with all his deep-theory rants when he wakes up at two in the morning and can't get back to sleep) and has a twelve-year-old son who is far too smart for his own good. When he isn't busy writing, organizing the working class, or fixing rich people's houses all day, he enjoys doing absolutely nothing on the couch, surrounded by his family and books by Gus Hall. Archives January 2022 In the Manifesto of the Communist Party the authors raised a list of 10 immediate objectives, the very first of which read’s: ‘1. Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.’ So the communists aimed to get rid of landed property, but what did they propose to replace it with? They wanted land nationalisation. The state would own all land and insofar as land was cultivated by entities that were not state farms, these would pay rent to the state for its use. Marx was quite adamant that it was not in the interest of the working class to allow land to pass into the ownership of rural associations. In his article The Nationalisation of Land [The International Herald No. 11, June 15, 1872;] he wrote: To nationalise the land, in order to let it out in small plots to individuals or working men's societies, would, under a middle-class government, only engender a reckless competition among themselves and thus result in a progressive increase of "Rent" which, in its turn, would afford new facilities to the appropriators of feeding upon the producers. "Small private property in land is doomed by the verdict of science, large land property by that of justice. There remains then but one alternative. The soil must become the property of rural associations or the property of the whole nation. The future will decide that question." I say on the contrary; the social movement will lead to this decision that the land can but be owned by the nation itself. To give up the soil to the hands of associated rural labourers, would be to surrender society to one exclusive class of producers Marx in this article argued against a system of small peasant proprietorship, arguing that the experience of France indicated that it led to the gradual subdivision of land into smaller and smaller family plots and that these small farms could not sustain the large scale mechanised agriculture needed to adequately feed a large working class. Why did Marx demand the allocation of rent to public purposes as part of the Nationalisation of land. Lenin explains this : Nationalisation of the land under capitalist relations is neither more nor less than the transfer of rent to the state. What is rent in capitalist society? It is not income from the land in general. It is that part of surplus value which re— mains after average profit on capital is deducted. Hence, rent presupposes wage-labour in agriculture, the transformation of the cultivator into a capitalist farmer, into an entrepreneur. Nationalisation (in its pure form) assumes that the state receives rent from the agricultural entrepreneur who pays wages to wage-workers and receives average profit on his capital—average for all enterprises, agricultural and non-agricultural, in the given country or group of countries. The aim therefore is to ensure that the portion of surplus, that must under relations of commodity production take the form of rent, is centrally appropriated and used for the development of the nation as a whole. The effectiveness of this policy is clearly born out by the comparative histories of China and India after independence. In China land was nationalised. The private appropriation of rent by a parasitic landlord class came to an end. In India that class survived, and continued to appropriate a large part of the surplus product. Without the drain imposed by landlords, China was able to develop rapidly, raise life expectancy and become the largest economy in the world. China/India GDP per capita current US$ , (World Bank) In addition to agricultural rent, capitalist society generates rent for minerals and urban land. The owners of land under which oil lies are able to extort a huge rent revenue. This revenue arises from the difference between the labour time necessary to produce oil on the most marginal reserves - those that for example require extensive fracking or those offshore in deep water - and the labour time necessary to produce oil on easily exploited reserves like those in Saudi Arabia. Similarly for urban land the rental that can be obtained relates to the differential labour costs of getting to work. A house 20 miles from the main employment center will command less rent than the same sized house 10 miles away. Workers must give up time and money to travel to work. Any saving they can make by living closer to work tends to end up in the hands of landlords who can charge more for a house close in to a great metropolis. It is evident, if the two houses are the same size and quality, that the premium in the second case is due to the land on which the house rests. Owner occupiers do not escape this. The price of property in a capitalist market is set by the price landlords are willing to bid to buy houses and flats as rental investment. A landlord will be willing to buy a house if the expected rent revenue is less than the interest he would pay on a bank loan used to purchase it. As cities expand, areas which were once marginal suburbs become embedded within the metropolis. Houses in them which originally commanded low rents are now let for high rents. This reacts back on property prices as illustrated from the following figure from my book How The World Works So landowners not only gain from increased rent, but make additional profits from the appreciation of property prices. Such speculative unearned income becomes a major driving force for the upper classes. I understand that slogans about ‘land back’ have started to be advanced in the USA, with the reference ‘back’ referring to the descendants of the indigenous or aboriginal peoples of the United States. Consider some possible interpretations of this.