|

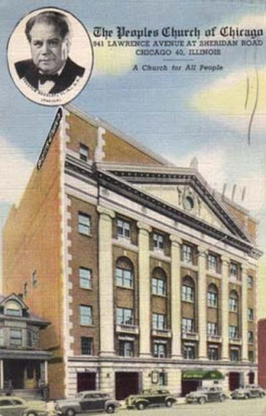

7/19/2024 Review: Bill Buell – George Lunn: The 1912 Socialist Victory in Schenectady (2019)By J.N. CheneyRead NowWith the surge in popularity of the Democratic Socialists of America since Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, it can be argued that there’s likewise been a surge in the successes of municipal socialism. Granted this is only concerning the electoral prospects of a single organization, but at least according to Wikipedia, there are nearly 150 people holding various positions within municipal governments ranging from the Mayoral office to smaller positions such as being members of a school board between 31 different states in the US. To understand the potential of these electoral results, or even the lack-there-of, historical examples need to be studied to absorb the lessons of these experiments. Could Bill Buell’s work “George Lunn: The 1912 Socialist Victory in Schenectady” serve as a lens into the achievements and shortcomings of socialism at the local level? Published in 2019, the county historian of Schenectady’s book holds the dual purpose of being a biography of George R. Lunn, a minister and politician, as well as more specifically examining his time as the only ever socialist mayor of Schenectady, New York. Lunn is also one of only four people to hold a mayoral office in New York State under some form of the socialist banner, as well as being the first to do so. The first seven chapters of this book touch upon Lunn’s early life and connections to the pulpit, as well as giving some historical context to the city of Schenectady and the standing of socialism within the United States in the early 20th century. To put it briefly, Lunn was born in Iowa in 1873, served very briefly as a chaplain during the Spanish-American War, and would later become ordained as a Presbyterian minister after graduating from Union Theological Seminary in 1901. In 1904 Lunn would move to Schenectady when he was named as pastor for Schenectady’s First Reformed Church. It was as a minister that Lunn began to gain prominence, being cited as an engaging and charismatic speaker, using his platform in the church to talk not only about religious affairs, but to address corruption within the city and speak of societal ills such as homelessness and child labor. The minister’s rhetoric would result in him leaving First Reformed in 1910, leading him to form his own congregation through the People’s Church and, soon after, officially joining the Socialist Party of America near the end of that year. Chronicling George Lunn’s entrance to the SPA introduces the real meat and potatoes of this biographical piece, his political career. Buell chronicles Lunn’s quick rise to popularity and his election to Mayor of Schenectady on the socialist ticket, taking office in 1911. The efforts of Lunn and his associates to implement elements of socialism within the framework of capitalism such as introducing free garbage pickup and a protracted effort to improve the city’s parks are laid out, examining how Lunn introduced these as well as displaying the struggles that came with working to implement such programs. Lunn’s administration faced issues with Republicans, Democrats, and the Progressive party trying to block him from following through with such economic and social programs, as well as issues within the Socialist Party itself. Particularly, there were individuals and factions who considered Lunn to be not “socialist enough” in his practices. Famed writer Walter Lippmann for a short time served as part of Lunn’s cabinet, and his reason for leaving stems from that very critique. With Lunn’s politics being influenced more by the Social Gospel and reformism than any sort of scientific socialism, these specific critiques do hold water. Buell does provide an astute recounting of Lunn’s involvement in the Little Falls Textile Strike of 1912-1913, with the Mayor serving as one of the primary catalysts in giving that struggle national attention, and bringing significant figures in labor history to New York’s Mohawk Valley as well as Schenectady, including Bill Haywood, Matilda Rabinowitz, Helen Schloss, Joseph Ettor, and more. Explaining how Lunn balanced his commitments as Mayor, his involvement in the strike, and his potential bid to run for Congress shows just how multifaceted Lunn was in his ability to juggle responsibilities. In that same vein, Buell covers Lunn’s struggles within and eventual leaving of the SPA after his second term as Mayor as well as his later career in a concise manner, though one could argue that it was too concise since he only spent three chapters including an epilogue covering Lunn’s career after this leaving the SPA. Given that this book is more specifically about Lunn’s first term as Mayor of Schenectady with some emphasis on his second, this is understandable. That being said, it would’ve been interesting and beneficial to see some more emphasis on Lunn’s third term as mayor and other political actions after leaving socialism. Bill Buell’s book is informative and is generally well-written and digestible. Buell doesn’t dive very deeply into the major theoretical conflicts between Lunn and other members of the party. Besides a brief mention of Lincoln Steffen’s dissolution with the Soviet Union, there is no explicit political bias being pushed by this book, no upholding of the socialist boogeyman that so many would use a piece like this to demonize. However, there are some shortcomings. The first being that since this book is self-published, even with the aid of the Troy Book Makers, a handful of typos managed to slip through the cracks. Though unfortunate to see, these can be forgiven as such typos are few and far between throughout the entire 200+ page book. The biggest problem to be found though is the use of one particular source. Buell utilizes the book The Red Nurse: A Story of the Little Falls Textile Strike by Michael Cooney as a source when introducing Helen Schloss and her role in the strike. For one, this is a piece of historical fiction. There are true elements to the book’s story, but to use a dramatization of historical events as an academic source shouldn’t be acceptable. Additionally, according to others who have studied the strike and the life of Schloss such as playwright Angela Harris, there are various inaccuracies in The Red Nurse. One example being that in the novel, Cooney says that Schloss resigned from a position she held in Little Falls in a rather vitriolic manner, when all actual accounts show that she resigned in a cordial manner. The story of George R. Lunn’s life and political career is not an unknown one given that there are a handful of academic articles and book chapters about the man and his career, as well as even having his own dedicated Wikipedia page. With that knowledge though, Buell’s piece serves as one of the only books dedicated to the life and times of the minister, the only other one that comes to mind being George Gardner’s The Schenectadians published in 2001. It’s not a perfect book given the aforementioned shortcomings, but George Lunn: The 1912 Socialist Victory in Schenectady is worth reading and analyzing for a look at the popularity of socialism at the time in addition to the benefits and shortcomings of municipal socialism. AuthorJ.N. Cheney is an aspiring Marxist historian with a BA in history from Utica College. His research primarily focuses on New York State labor history, as well as general US socialist history. He additionally studies facets of the past and present global socialist movement including the Soviet Union, the DPRK, and Cuba. Archives July 2024

0 Comments

Originally published: In Defense of Marxism on May 24, 2024 by Ben Curry (more by In Defense of Marxism) (Posted Jun 24, 2024) Honoré de Balzac is renowned as a prolific literary genius and was one of Marx and Engels’ favourite authors. He was a pioneer of the Realist style that would be taken up by such famous authors as Émile Zola and Charles Dickens. In this article, Ben Curry explores Balzac’s Realist method, the predominant themes of his vast body of work, known collectively as The Human Comedy, and the fascinating paradox that lies at its heart. You’re deluding yourself, dear angel, if you imagine that it’s King Louis-Philippe that we’re ruled by, and he has no illusions himself on that score. He knows, as we all do, that above the Charter there stands the holy, venerable, solid, the adored, gracious, beautiful, noble, ever-young, almighty, Franc! The period between the great revolutions of 1789 and 1848 was one of unprecedented upheaval in France. This was the epoch of the galloping advance of the French bourgeoisie. At its outset, this class formed part of the oppressed ‘Third Estate’ under the absolutist Bourbon regime; by its close, it was the undisputed ruling class and had begun to transform French society in its own image. Contemporary with this era of storm and stress, at one and the same time its historian and the artist who best depicted its moving spirit, lived one of the giants of world literature, the father of the Realist novel, Honoré de Balzac. Balzac, a favourite of Marx and Engels, was no revolutionary. Quite the contrary. And yet, Engels was able to say of his immense literary output: There is the history of France from 1815 to 1848… And what boldness! What a revolutionary dialectic in his poetical justice! A lifetime of furious nocturnal work, fuelled by immense quantities of coffee (it is estimated that he drank 500,000 cups in his lifetime!), sent Balzac to a tragically early grave at the age of just 50. In two decades of work, however, Balzac penned no fewer than 90 novels, novellas and short stories—60 of them full-length novels, and dozens of them masterpieces in their own right. But Balzac’s novels, great as they are taken singly, cannot be fully appreciated other than in connection with each other. His tremendous opus, known collectively as The Human Comedy, represents a single, masterful panorama of French society from the fall of Napoleon until 1848: Paris and the provinces; soldiers, police spies and politicians; aristocrats and peasants; bankers, artists, journalists, bureaucrats, criminals and courtesans—all are expertly depicted with strokes that cut straight to the heart of their world. More than a portrayal of French society, it portrays bourgeois society as it was and as it is: petty, grasping and brutal. The Realist novel Balzac was born in 1799, the same year that Napoleon overthrew the Directory, marking the closing chapter of the French Revolution that had aroused and dashed such immense illusions among the downtrodden masses of France. One form of exploitation had been exchanged for another. In the words of Marx and Engels, “for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions,” the bourgeoisie “substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.” With the victory of the bourgeoisie, the authors of The Communist Manifesto explained how man was “at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.” In the volumes of The Human Comedy, Balzac’s art acted like powerful smelling salts, assisting in sobering up this world whose illusions were crashing down around it, forcing it to look reality in the face. Instead of a retreat into an idealised past in the Romantic style then all the rage in France, we find the present, with its sores and all, fully on display. Balzac’s method was wholly materialist. Under the banner of ‘Realism’, it represented a new departure in literature and the arts at large. Stefan Zweig, in his essay on the genius of Balzac, gives a vivid description of his method: The idea—which he christened ‘Lamarckism’, and which Taine was later to petrify into a formula—that every multiplicity reacts upon a unity with no less vigour than does a unity upon a multiplicity, that each individual is a product of climate, of the society in which he is reared, of customs, of chance, of all that fate has brought his way, that each individual absorbs the atmosphere by which he is surrounded as he grows to adulthood and in his turn radiates an atmosphere which others will absorb; this universal influence of the world within and the world without upon the formation of character, became an axiom with Balzac. Everything flows into everything else; all forces are mobile, and not one of them is free—such was his view. Although Balzac explicitly rejected the label ‘materialist’, what is this but a clearly materialist method? And, what is more, it is an extremely dialectical method. Balzac intended The Human Comedy to be a complete, living representation of all the “social species” that inhabit the world, not simply a dry accumulation of ‘facts’. No art can ever hope to chronicle every one of society’s details; nor does it need to. The real purpose of art is to reach beyond the accidental in order to grasp deeper, more essential truths. Balzac didn’t need to portray 30 million Frenchmen and women to give a portrait of France. It was enough to capture the essential types of the age. With his pen, the 2,000 or so characters of The Human Comedy sufficed for this task. In The Human Comedy—perhaps counterintuitively for a work of Realism—we find men and women painted in bold, exaggerated colours, as Renaissance painters used the method of chiaroscuro, the bold opposition of dark and light, to highlight the drama in human expressions and motion. Balzac’s characters are frequently depicted as unusually singular in their passions. But they are all the more real for that fact: they form archetypes of their class and of their motivating passions. Baron de Nucingen stands in as the archetype of the whole class of millionaire bankers; Grandet plays the same role for misers; Gobseck for usurers; Crevel for bourgeois parvenus; Madame Marneffe for the bourgeois courtesan; de Rastignac and de Rubempré for ambitious provincials; and Vautrin for the whole criminal underclass of Paris. Just as the chemist breaks down for analysis the innumerable compound substances of nature into their purified constituent elements, so Balzac sought to “analyse into its component parts the elements of that compound mass which we call ‘the people’”. Balzac’s ability, as he put it, “to rise to the level of others”, “to espouse their way of life”, “to feel their rags on his shoulders” was something unequalled: I looked into their souls without failing to notice externals, or rather I grasped these external features so completely that I straightaway saw beyond them.

In the earliest novel in The Human Comedy, Les Chouans set in 1799, we meet the aristocratic leaders of the Chouannerie—a reactionary guerrilla rising in Brittany. In Les Chouans the Republican army is a disciplined fighting force, consisting of peasants who earnestly imagine their First Consul Napoleon to be the defender of the land they actually gained thanks to the Revolution. On the other hand the Chouan guerrillas, consisting of Breton peasants, are depicted as having joined the Royalist ranks merely to rob stagecoaches and the bodies of dead Republican soldiers—a practice solemnly sanctified at clandestine forest Masses by the Church. As for their aristocratic leaders, we get their full measure when they confront their leader to greedily press their demands for titles, estates and archbishoprics as reward for their continued allegiance to the King. In Lost Illusions and Père Goriot, we find the old nobility: petty, bigoted, two-faced and egotistical, restored once more in the saddle, thanks to the reactionary armies of Europe. But it was one thing for Louis XVIII to re-establish his Court and for the aristocracy to re-establish their salons in Paris, it was quite another to establish the old property relations on which the Ancien Régime once stood. France had been changed irrevocably, and money formed the new axis around which it now turned. The rising bourgeoisie pressed against the old aristocracy in every sphere: in the theatre box, in politics, in the press. The faded nobles might scorn admitting the upstarts to their salons, but it was to the Stock Exchange that they entrusted their fortunes. It was to the bourgeois timber agents that they sold the wood felled from the forests of their manors, and it was to the bourgeois usurer that they turned to fund their marital infidelities. In the provinces, where the nobility found itself on a slightly firmer footing, Balzac describes the most worthless rabble: All the people who gathered there had the most pitiable mental qualities, the meanest intelligence, and were the sorriest specimens of humanity within a radius of fifty miles. Political discussions consisted of verbose but impassioned commonplaces: the Quotidienne was regarded as lukewarm in its royalism; Louis XVIII himself was considered to be a Jacobin. The women were mostly stupid, devoid of grace and badly dressed; every one of them was marred by some imperfection; everything fell short of the mark, conversation, clothes, mind and body alike… Nevertheless, comportment and class consciousness, gentlemanly airs, the arrogance of the lesser nobility, acquaintance with the rules of decorum, all served to cloak the void within them. What is this if not a class that was doomed to extinction and deserving of its fate? Balzac’s beloved Catholic Church is depicted as little better. Like all the last bastions of the old order, it found itself besieged from all directions and forced to become bourgeois itself: “It stoops, in the house of God, to a disgraceful traffic in pew rents and chairs… although it cannot have forgotten Christ’s anger when he drove the moneychangers from the Temple.” In birth, marriage and death, we find the representatives of the Church, with their palm extended, collecting their fee at every stage.

Throughout The Human Comedy we can read fictitious accounts of the numerous, real tragedies of what family life in particular becomes under capitalism. We find fathers swindling sons; men wooing women for dowries; adulterous fathers ruining families to support mistresses; daughters placed on bread and water by rich and ‘thrifty’ miser-fathers; husbands aiding their wives’ infidelities for career advancement; children treated as chattel by parents. As Marx and Engels put it, The bourgeoisie has torn away from the family its sentimental veil, and has reduced the family relation to a mere money relation. Criminals and capitalists Balzac’s critique touches in turn upon all aspects of bourgeois society, only a few of which can be mentioned here. In Père Goriot, a retelling of Shakespeare’s tragedy King Lear in the bourgeois age, the real hero of that story, if he can be called such, is Eugene de Rastignac, an impoverished provincial nobleman. A new arrival in Paris, he is drawn between two ways to make his fortune: the ‘honest’ method, of seducing one of Père Goriot’s daughters, made wealthy through marriage to the banker de Nucingen; or through a shortcut involving the shedding of blood, offered by the branded criminal Vautrin. What is the difference? In the opinion of Vautrin, who counsels de Rastignac through his pangs of conscience, the difference is little more than moral and legal hypocrisy: There’s not one article [of the law] that does not lead to absurdity. The smooth-tongued man in his smart yellow gloves has committed murders without bloodshed, but someone has been bled all the same; the actual murderer has jemmied open a door; two deeds of darkness! The capitalist kills just as surely as the murderer, although without spilling a drop of blood himself. The words of condemnation thrown in the face of the whole of bourgeois society do not fail to hit their target on account of being placed in the mouth of a branded miscreant: Are you any better than us? The brand we bear on our shoulders is not as shameful as what you have in your hearts, flabby members of a putrid society. Ultimately, de Rastignac is forced to agree with Vautrin: He saw the world as it is: laws and morality unavailing with the rich, wealth the ultima ratio mundi. ‘Vautrin is right, wealth is virtue,’ he said to himself.