|

In the year of the Russian presidency of BRICS, the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) had to deliver something special.

And deliver it did: over 21,000 people representing no less than 139 nations – a true microcosm of the Global Majority, discussing every facet of the drive towards a multipolar, multinodal (italics mine), polycentric world. St. Petersburg, beyond all the networking and the frantic deal-making – $78 billion-worth clinched in only three days – crafted three intertwined key messages already resonating all across the Global Majority.

Message Number One:

President Putin, a “European Russian” and true son of this dazzling, dynamic historic marvel by the Neva, delivered an extremely detailed one-hour speech on the Russian economy at the forum’s plenary session. The key takeaway: as the collective West launched total economic war against Russia, the civilization-state turned it around and positioned itself as the world's 4th largest economy by purchasing power parity (PPP). Putin showed how Russia still carries the potential to launch no less than nine sweeping – global – structural changes, an all-out drive involving the federal, regional, and municipal spheres. Everything is in play – from global trade and the labor market to digital platforms, modern technologies, strengthening small and medium-sized businesses and exploring the still untapped, phenomenal potential of Russia's regions. What was made perfectly clear is how Russia managed to reposition itself beyond sidestepping the – illegitimate – sanctions tsunami to establishing a solid, diversified system oriented towards global trade – and completely linked to the expansion of BRICS. Russia-friendly states already account for three-quarters of Moscow’s trade turnover. Putin’s emphasis on the Global Majority’s accelerated drive to strengthen sovereignty was directly linked to the collective West doing its best – rather, worst – to undermine trust in their own payment infrastructure. And that leads us to… Glazyev and Dilma rock the boat. Message Number Two: That was arguably the major breakthrough in St. Petersburg. Putin stated how the BRICS are working on their own payment infrastructure, independent from pressure/sanctions by the collective West. Putin had a special meeting with Dilma Rousseff, president of the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB). They did talk in detail about the bank’s development – and most of all, as later confirmed by Rousseff, about The Unit, whose lineaments were first revealed exclusively by Sputnik: an apolitical, transactional form of cross-border payments, anchored in gold (40%) and BRICS+ currencies (60%). The day after meeting Putin, president Dilma had an even more crucial meeting at 10 am in a private room at SPIEF with Sergey Glazyev, the Minister for Macro-Economy at the Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU) and member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Glazyev, who had previously provided full academic backing to the Unit concept, explained all the details to President Dilma. They were both extremely pleased with the meeting. A beaming Rousseff revealed that she had already discussed The Unit with Putin. It was agreed there will be a special conference at the NDB in Shanghai on The Unit in September. This means the new payment system has every chance to be at the table during the BRICS summit in October in Kazan, and be adopted by the current BRICS 10 and the near future, expanded BRICS+. Now to… Message Number Three: It had to be, of course, about BRICS – which everyone, Putin included, stressed will be significantly expanded. The quality of the BRICS-related sessions in St. Petersburg demonstrated how the Global Majority is now facing a unique historical juncture – with a real possibility for the first time in the last 250 years to go all-out for a structural change of the world-system. And it’s not only about BRICS. It was confirmed in St. Petersburg that no less than 59 nations – and counting – plan to join not only BRICS but also the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU). No wonder: these multilateral organizations now finally have established themselves on the forefront of the drive towards the multimodal (italics mine) – and to quote Putin in his address – "harmonic multipolar world". The Top Sessions for Further Reference All of the above could be followed, live, during the frantic two and a half days of forum’s sessions. This is a sample of what were arguably the most engaging. The broadcasts should be very helpful as references going forward – all the way to the BRICS summit in October, and beyond. On the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and Arctic expansion. Best motto of the session: “We need icebreakers!” The essential discussion to understand how the current global trade supply chains are not reliable anymore and how the NSR is faster, cheaper and reliable. On the BRICS business expansion. On the BRICS goals for a true new world order. On the 10 years of the EAEU. On the closer integration between EAEU and ASEAN. The BRICS+ roundtable on the International North South Transportation Corridor (INSTC). This session was particularly crucial. The key actors of the INSTC are Russia, Iran and India – all BRICS members. Actors on the margins which will profit from the INSTC – from the Caucasus to Central and South Asia – are already interested to be part of BRICS+. Igor Levitin, a top Putin advisor, was a key figure in this session. The Greater Eurasia Partnership (GEP). This was an essential discussion on what is eminently a civilizational project – in contrast with the collective West’s exclusionary approach. The discussion shows how GEP interlinks with SCO, EAEU and ASEAN and stresses the inevitable complementarity of transport, logistics, energy and payment structure all across Eurasia. Glazyev, Deputy Prime Minister Alexey Overchuk and former Austrian Foreign Minister Karin Kneissl – always ultra-sharp – are key participants. Extra – astonishing – bonus: Adul Umari, acting Minister of Labor in Taliban Afghanistan, interacting with his Eurasia partners. On the philosophy of multipolarity. Conceptually, this session interacts with the GEP session. It offers the perspective of a concise inter-civilizational dialogue under the framework of BRICs+. Alexander Dugin, the irrepressible Maria Zakharova and Professor Zhang Weiwei of Fudan University are among the participants. On Polycentricity. That involves all Global Majority institutions: BRICS, SCO, EAEU, CIS, CSTO, CICA, African Union, the renewed Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Glazyev, Maria Zakharova, Senator Pushkov and Alexey Maslov – director of the Institute of Asian and African Studies at Moscow State University – discuss how to build a polycentric system of international relations. As Project Ukraine Faces Doom… Finally, it’s inevitable to contrast the – hopeful, auspicious – mood at SPIEF with the collective West’s hysterics as Project Ukraine faces doom. Putin made it quite clear: Russia will prevail, no matter what. The collective West may rekindle “the Istanbul solution”, as Putin noted, but modified “based upon the new reality” in the battlefield. Putin also deftly defused all the pre-fabricated, nonsensical nuclear paranoia infesting Atlanticist circles. Still, that won’t be enough. On the packed corridors at SPIEF, and in informal meetings, there was total awareness about the Hegemon’s desperation-fueled warmongering masked as "defense." There were no illusions that the current dementia posing as “foreign policy” is betting on a genocide not only for the sake of the “aircraft carrier” in West Asia but mostly to cow the Global Majority into submission.

That would raise the serious possibility that the Global Majority needs to build a military alliance to deter this – planned – Global War.

Russia-China, of course, plus Iran and credible Arab deterrence – with Yemen showing the way: all of that may become a must. A Global Majority military alliance will have to show up one way or another: either before the – incoming, planned – disaster, to mitigate it; or after it has totally engulfed West Asia into a monstrous, vicious war. Ominously, we may be nearly there. But at least St. Petersburg offered glimmers of hope. Putin: "Russia will be the heart of the multipolar harmonic world." Now that’s how you clinch a one-hour speech. AuthorPepe Escobar

This article was produced by Sputnik International.

ArchivesJuly 2024

0 Comments

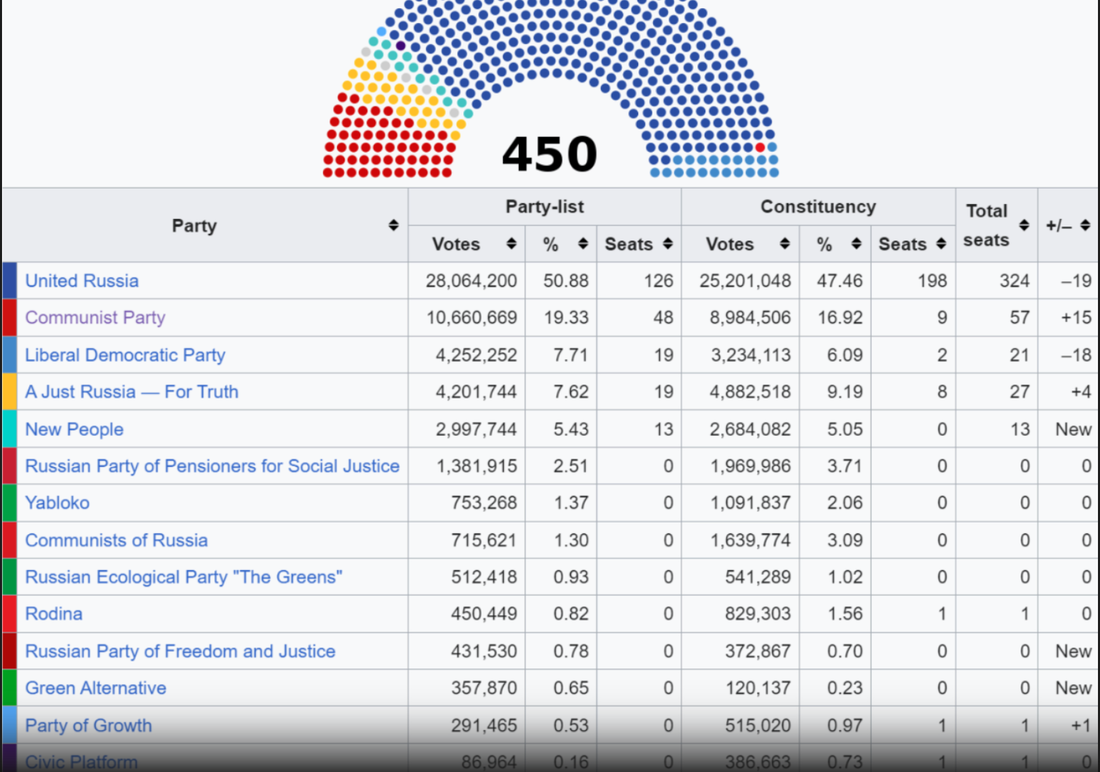

Think about this: when well-informed Americans engage in discussions about American politics, they reveal a thorough grasp of the intricate workings of the American government. They can conduct in-depth analyses on topics such as the influence of the Squad on Democratic Party policies and even assess the policy proposals of third-party candidates like Robert F, Kennedy or Cornell West. They can discuss the historical dynamics between institutions like the FBI and the CIA, noting differences between eras such as Hoover's and Mueller's leadership. Moreover, with sufficient knowledge, they can investigate the impact of financial entities like Citibank, Goldman Sachs, or BlackRock on cabinet selections and recognize the various vested interests involved, such as the appointment of people like Tom Vilsack as Secretary of Agriculture. Similarly, well-informed Brits will tell you many details on the latest drama between Labour and Tories, and Canadians may provide insights into the deeper political meanings behind actions like Pierre Poilievre eating an apple. Beyond the borders However, when asked about the politics of foreign countries, individuals tend to oversimplify, reducing complex political landscapes to singular figures. For instance, ask the average American about Russia's government, and the response often centers around Putin or Putinism. The same applies to China, where discussions typically focus solely on Xi Jinping, and the only thing they may know about the DPRK is their leader - Kim Jong Un. This oversimplification fosters a problematic "Leader = Country" mindset, perpetuated even by some "independent media," which invariably portrays leaders like Xi, Putin, and Jong Un as evil dictators. Foreign nations, like one's own, are multifaceted entities with diverse interests, power struggles, and internal conflicts. Yet, many fail to recognize this complexity. Consider how many Russian politicians you can name beyond Putin, or how many parties Russia has. How familiar are you with their backgrounds, ideologies, and roles in Russian politics? How many policies can you attribute to them? If you're struggling to answer these questions, you're not alone. So, can we deepen our understanding of geopolitics by challenging this simplistic "Leader = Country" narrative? Roughly 70% of Americans want the Biden administration to push Ukraine toward a negotiated peace with Russia as soon as possible, according to a new survey from the Harris Poll and the Quincy Institute. And for that reason, we need to understand Russian politics better. Let's explore together. Russian Political Structure There's a prevalent misconception among many people, particularly in Western countries, that Alexei Navalny was the sole opposition figure in Russian politics. But in reality, Russia's political landscape is much broader, with various opposition figures, parties, and movements operating within it. Russia's political structure is shaped by its history, culture, and unique socio-political dynamics. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has undergone significant transformations, particularly in its political system. Today, the country operates under a semi-presidential republic, in which the president holds substantial power alongside a bicameral legislature and various political parties are vying for influence. Let's delve into the intricacies of Russia's political structure and examine the key parties and their positions. The Kremlin's Dominance: United Russia At the center of Russian politics stands United Russia, the ruling party known for its close affiliation with the Kremlin and President Vladimir Putin. Founded in 2001, United Russia has consistently maintained its dominance in the political arena, securing significant majorities in both the State Duma (the lower house of parliament) and regional legislatures. United Russia positions itself as a centrist party, advocating for stability, economic development, and national unity. However, critics often label it as a vehicle for consolidating power under Putin's leadership, with some accusing it of suppressing opposition voices and limiting political pluralism. The Communist Party: A Legacy of the Soviet Era The Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) remains a prominent force in Russian politics and is the main opposition party. Founded in 1993 as the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party, the CPRF espouses socialist principles, advocating for justice and the protection of workers' rights. The CPRF maintains a significant presence in the State Duma and enjoys support primarily from older demographics nostalgic for the stability of the Soviet era. It criticizes United Russia's policies as serving the interests of the elite. Liberal Opposition In contrast to United Russia and the CPRF, liberal opposition parties such as Yabloko represent a minority voice within Russia's political landscape. Founded in the early 1990s, Yabloko advocates for democratic reforms, civil liberties, and market-oriented economic policies. Yabloko's platform emphasizes the rule of law, human rights, and the decentralization of power away from the Kremlin. However, the party struggles to gain significant traction, often facing obstacles such as limited media coverage and electoral barriers. Nationalist Forces: LDPR and A Just Russia Completing the spectrum of Russia's political parties are the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) and A Just Russia. Despite their ideological differences, both parties share nationalist sentiments and occasionally align with the Kremlin on certain issues. The LDPR, previously led by the charismatic Vladimir Zhirinovsky, combines populist rhetoric with nationalist policies, advocating for a strong Russian state and assertive foreign policy. A Just Russia, on the other hand, positions itself as a social-democratic party, prioritizing social welfare programs and progressive taxation while also supporting Putin's presidency. Despite many socialist elements in its domestic policies, Russia today remains a capitalist country. Moscow’s foreign policy has become anti-imperialist out of necessity. After years of offensive actions from NATO, the Russian government has had no choice but to intervene to safeguard its sovereignty. Only time will tell how successful their fight with the Empire will be. Our job is to support Russia and others who oppose Western hegemony and seize the right opportunity for Socialist Revolution. AuthorSlava the Ukrainian Socialist This article was produced by The Revolution Report. Archives April 2024 9/19/2023 Pepe Escobar: Russia, North Korea Stage 'Strategic Coup' Against Western HegemonyRead Now

It will take ages to unpack the silos of information inbuilt in the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok last week, coupled with the – armored - train-keeps-a-rollin’ conducted by North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un straddling every nook and cranny of Primorsky Krai.

The key themes all reflect the four main vectors of the New Great Game as it’s being played across the Global South: energy and energy resources; manufacturing and labor; market and trade rules; and logistics. But they go way beyond – exploring the subtle nuances of the current civilizational war.

So Vladivostok presented…

- A serious debate on the surge of anti-neocolonialism, presented for instance by the Myanmar delegation; geostrategically, Burma/Myanmar, as a privileged gateway to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, was always an object of Divide and Rule games, with the British Empire only caring about extracting natural resources. This is what “scientific colonialism” is all about. - A serious debate on the concept of the civilization-state, as already developed by Chinese and Russian scholars, applied to China, Russia, India and Iran. - The interconnection of transport/connectivity corridors. That includes the upgrading of the Trans-Siberian in the near future; a boost for the Trans-Baikal – the world’s busiest rail line – connecting the Urals to the Far East; a renewed drive for the Northern Sea Route (last month two Russian oil tankers sailed from Murmansk across the Arctic to China for the first time; ten days shorter than the Suez Canal route); and the coming of the Chennai-Vladivostok channel, which will be connected to the International North South Transportation Corridor (INTSC). - The common Eurasia payment system, discussed in detail in one of the key panels: Greater Eurasia: Drivers for the Formation of an Alternative International and Monetary and Financial System. The immense challenge to set up a new payment settlement currency against “toxic currencies” instrumentalized amid relentless Hybrid War. In another panel, the possibility of a timely BRICS and EAEU joint summit next year has been evoked.

All Aboard The Kim Train

The genesis of Kim Jong Un’s train journey to the Russian Far East - coinciding with the Forum, no less - is a masterful strategic coup that was in the works since 2014, at the time of the Maidan. Xi Jinping was still in the beginning of his first mandate; he had announced the New Silk Road exactly ten years ago, first in Astana and then in Jakarta. The DPRK was not supposed to be integrated into this vast pan-Eurasian project that would soon become China’s overarching foreign policy concept. The DPRK then was on a roll against the Hegemon, under Obama, and Beijing was no more than a worried spectator. Moscow, of course, was always focused on peace in the Korean Peninsula, especially because its geopolitical priorities in 2014 were Donbass and Syria/Iran. The last thing Moscow could afford was a war in Asia-Pacific. Putin’s strategy was to send Defense Minister Shoigu to Beijing and Islamabad to calm it all down. Pakistan at the time was helping Pyongyang to weaponize their nuclear arsenal. Simultaneously, Putin himself approached Kim, offering serious guarantees: we’ve got your back if ever there is an attack by the Hegemon supported by Seoul. Even better: Putin got Xi himself to double down on the guarantees.

The categorical imperative was simple: as long as Pyongyang did not start any trouble, Moscow and Beijing would be by its side.

A sort of calm before any possible storm then set in – even if Pyongyang continued to test their missiles. So over the years, Kim’s mindset changed; he became convinced that Russia and China were his allies. The DPRK's geoeconomic integration into Eurasia was seriously discussed in previous, pre-Covid editions of the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok. That included the tantalizing possibility of a Trans-Korean Railway linking both North and South to the Far East, Siberia and the wider Eurasia. So Kim started to see the Big Eurasia Picture, and how Pyongyang could finally start to benefit geoeconomically from a closer association with the EAEU, SCO and BRI. This is how strategic diplomacy works: you invest during a decade, and then all the pieces fall into place when an armored train keeps-a-rollin’ across Primorsky Krai. From the perspective of a Russia-China-DPRK triangle, it’s no wonder the collective West has been reduced to the status of crying toddlers in a sandbox. The Hegemon’s puny US-Japan-South Korea axis to counter, simultaneously, China and the DPRK, is a joke compared to the DPRK’s brand-new role as a sort of Asia-Pacific Military District, adjacent to their immediate neighbor, the Russian Far East. There will be military integration, of course, in missile defense, radars, ports, airfields. But the key vector, along the way, will be geoeconomic integration. Sanctions from now on are meaningless. No one in 2014 was seeing this all play out, except for a very sharp analyst who coined the precious Double Helix concept to define the still evolving, at the time, Russia-China comprehensive strategic partnership. The Double Helix perfectly explains the full-spectrum geostrategic symbiosis between two civilization-states which happen to be former empires but since the middle of the previous decade willfully decided to accelerate their mutual drive to lead the Global Majority in the path towards multipolarity.

The Road to Polycentricity

All of the above finely coalesced in the last panel in Vladivostok - informally known even to the Japanese and Koreans as “the European capital of Asia”, in the heart of Asia-Pacific. The debate was on a “global alternative to Western dominance”. The West, incidentally, was absolutely invisible at the Forum. Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova summed it all up: the recent G20 and BRICS summits had set the stage for President Putin’s remarkable address to the plenary session in Vladivostok. Zakharova alluded to “fantastic strategic patience”. That applies to the whole “pivot to Asia” policy and boosting the development of the Far East, initiated in 2012, and now implying a full turn of the Russian economy towards Asia-Pacific geoeconomics. But at the same time, that also applies to integrating the DPRK into the geoeconomic Eurasian high-speed train.

Zakharova stressed how Russia “never supported isolation”; always “advocated partnership” – which the Forum graphically displayed for dozens of Global South delegations. And now, under the conditions of a “dirty fight, unlawful and with no rules”, a serious stand-off, the Russian position remains easily recognizable for the Global Majority: “Not to accept dictatorship”.

Andrey Denisov, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, made a point to mention crack political analyst Sergey Karaganov as one of the key drivers of the concept of Greater Eurasia. More than “multipolarity”, Denisov argued, what is being built is “polycentricity”: a series of concentric circles, involving plenty of dialogue partners. Former Austrian Foreign Minister Karin Kneissl now heads a new think tank in St. Petersburg, G.O.R.K.I. As a European who ended up being ostracized by her own peers under the blatant toxicity of cancel culture, she stressed how freedom and rule of law have disappeared in Europe. Kneissl referred to the Battle of Actium as the key passage of power from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Western Mediterranean: “That’s when the dominance of the West started”, complete with all the mythology built around the Roman Empire which obsesses the Anglosphere to this day. With sanctions dementia and irrational Russophobia installed at the head of the EU and the European Commission, Kneissl stressed, the notion that “treaties must be preserved” disappeared while “the rule of law has been destroyed. This is the worst that could have happened to Europe”. Alexander Dugin, online, called for understanding “the depth of Western domination”, expressed via hyper-liberalism. And he proposed a key breakthrough: the Western modus operandi should become an object of research, in a sort of Gramscian attempt to define what distinguishes Western ideology, and thus act towards “deep decolonization”.

In a sense this is what is being attempted by current actors in West Africa – Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger. That poses the question of who is a real Sovereign in a new world. The West, argues Dugin, is a Total Sovereign; Russia, as a nuclear power and prime military power defined as an existential threat by the Hegemon, is also a Sovereign.

Then there’s China, India, Iran, Turkey. These are key poles in a dialogue of civilizations; actually what was proposed by former Iranian President Khatami way back in the late 1990s, and then dismissed by the Hegemon. Dugin remarked how China “has moved far away in building a civilizational state”. Russia, Iran, India are not far behind. These will be the essential actors steering the world towards polycentricity. AuthorPepe Escobar

This article was produced by Sputnik.

ArchivesSeptember 2023 War, it seems, was the only option Russia’s opponents had ever considered. Russian President Vladimir Putin with then German Chancellor Angela Merkel on May 10, 2015, at the Kremlin. (Russian Government) Recent comments by former German Chancellor Angela Merkel shed light on the duplicitous game played by Germany, France, Ukraine and the United States in the lead-up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February. While the so-called “collective west” (the U.S., NATO, the E.U. and the G7) continue to claim that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was an act of “unprovoked aggression,” the reality is far different: Russia had been duped into believing there was a diplomatic solution to the violence that had broken out in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine in the aftermath of the 2014 U.S.-backed Maidan coup in Kiev. Instead, Ukraine and its Western partners were simply buying time until NATO could build a Ukrainian military capable of capturing the Donbass in its entirety, as well as evicting Russia from Crimea. In an interview last week with Der Spiegel, Merkel alluded to the 1938 Munich compromise. She compared the choices former British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had to make regarding Nazi Germany with her decision to oppose Ukrainian membership in NATO, when the issue was raised at the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest. By holding off on NATO membership, and later by pushing for the Minsk accords, Merkel believed she was buying Ukraine time so that it could better resist a Russian attack, just as Chamberlain believed he was buying the U.K. and France time to gather their strength against Hitler’s Germany The takeaway from this retrospection is astounding. Forget, for a moment, the fact that Merkel was comparing the threat posed by Hitler’s Nazi regime to that of Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and focus instead in on the fact that Merkel knew that inviting Ukraine into NATO would trigger a Russian military response. Rather than reject this possibility altogether, Merkel instead pursued a policy designed to make Ukraine capable of withstanding such an attack. War, it seems, was the only option Russia’s opponents had ever considered. Merkel and Joe Biden kissing at 2015 Munich Security Conference with then Secretary of State John Kerry. (Mueller/MSC/Flickr) Putin: Minsk Was a Mistake Merkel’s comments parallel those made in June by former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko to several western media outlets. “Our goal,” Poroshenko declared, “was to, first, stop the threat, or at least to delay the war — to secure eight years to restore economic growth and create powerful armed forces.” Poroshenko made it clear that Ukraine had not come to the negotiating table on the Minsk Accords in good faith. This is a realization that Putin has come to as well. In a recent meeting with Russian wives and mothers of Russian troops fighting in Ukraine, including a few widows of fallen soldiers, Putin acknowledged that it was a mistake to agree to the Minsk accords, and that the Donbass problem should have been resolved by force of arms at that time, especially given the mandate he had been handed by the Russian Duma regarding authorization to use Russian military forces in “Ukraine,” not just Crimea. Putin’s belated realization should send shivers down the spine of all those in the West who operate on the misconception that there can now somehow be a negotiated settlement to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. None of Russia’s diplomatic interlocutors have demonstrated a modicum of integrity when it comes to demonstrating any genuine commitment to a peaceful resolution to the ethnic violence which emanated from the bloody events of the Maidan in February 2014, which overthrew an OSCE-certified, democratically-elected Ukrainian president. Response to ResistanceUkrainian government tank fire against Donbass. (Ukraine MOD) When Russian speakers in Donbass resisted the coup and defended that democratic election, they declared independence from Ukraine. The response from the Kiev coup regime was to launch an eight-year vicious military attack against them that killed thousands of civilians. Putin waited eight years to recognize their independence and then launched a full-scale invasion of Donbass in February. He had previously waited on the hope that the Minsk Accords, guaranteed by Germany and France and endorsed unanimously by the U.N. Security Council (including by the U.S.), would resolve the crisis by giving Donbass autonomy while remaining part of Ukraine. But Kiev never implemented the accords and were not sufficiently pressured to do so by the West. The detachment shown by the West, as every pillar of perceived legitimacy crumbled — from the OSCE observers (some of whom, according to Russia, were providing targeting intelligence about Russian separatist forces to the Ukrainian military); to the Normandy Format pairing of Germany and France, which was supposed to ensure that the Minsk Accords would be implemented; to the United States, whose self-proclaimed “defensive” military assistance to Ukraine from 2015 to 2022 was little more than a wolf in sheep’s clothing — all underscored the harsh reality that there never was going to be a peaceful settlement of the issues underpinning the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. And there never will be. War, it seems, was the solution sought by the “collective West,” and war is the solution sought by Russia today. Sow the wind, reap the whirlwind. On reflection, Merkel was not wrong in citing Munch 1938 as an antecedent to the situation in Ukraine today. The only difference is this wasn’t a case of noble Germans seeking to hold off the brutal Russians, but rather duplicitous Germans (and other Westerners) seeking to deceive gullible Russians. This will not end well for either Germany, Ukraine, or any of those who shrouded themselves with the cloak of diplomacy, all the while hiding from view the sword they held behind their backs. Scott Ritter is a former U.S. Marine Corps intelligence officer who served in the former Soviet Union implementing arms control treaties, in the Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Storm and in Iraq overseeing the disarmament of WMD. His most recent book is Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika, published by Clarity Press. The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News. AuthorScott Ritter This article was republished from Consortium News. Archives December 2022 11/7/2022 The West Must Stop Blocking Negotiations Between Ukraine and Russia By: Vijay PrashadRead Now Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022. This war has been horrendous, though it does not compare with the terrible destruction wrought by the U.S. bombardment of Iraq (“shock and awe”) in 2003. In the Gomel region of Belarus that borders Ukraine, Russian and Ukrainian diplomats met on February 28 to begin negotiations toward a ceasefire. These talks fell apart. Then, in early March, the two sides met again in Belarus to hold a second and third round of talks. On March 10, the foreign ministers of Ukraine and Russia met in Antalya, Türkiye, and finally, at the end of March, senior officials from Ukraine and Russia met in Istanbul, Türkiye, thanks to the initiative of Türkiye’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. On March 29, Türkiye’s Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu said, “We are pleased to see that the rapprochement between the parties has increased at every stage. Consensus and common understanding were reached on some issues.” By April, an agreement regarding a tentative interim deal was reached between Russia and Ukraine, according to an article in Foreign Affairs. In early April, Russian forces began to withdraw from Ukraine’s northern Chernihiv Oblast, which meant that Russia halted military operations around Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital. The United States and the United Kingdom claimed that this withdrawal was a consequence of military failure, while the Russians said it was due to the interim deal. It is impossible to ascertain, with the available facts, which of these two views was correct. Before the deal could go forward, then-UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson arrived in Kyiv on April 9. A Ukrainian media outlet—Ukrainska Pravda--reported that Johnson carried two messages to Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy: first, that Russian President Vladimir Putin “should be pressured, not negotiated with,” and second, that even if Ukraine signed agreements with the Kremlin, the West was not ready to do so. According to Ukrainska Pravda, soon after Johnson’s visit, “the bilateral negotiation process was paused.” A few weeks later, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin visited Kyiv, and following the trip, Austin spoke at a news conference at an undisclosed location in Poland and said, “We want to see Russia weakened.” There is no direct evidence that Johnson, Blinken, and Austin directly pressured Zelenskyy to withdraw from the interim negotiations, but there is sufficient circumstantial evidence to suggest that this was the case. The lack of willingness to allow Ukraine to negotiate with Russia predates these visits and was summarized in a March 10, 2022, article in the Washington Post where senior officials in U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration stated that the current U.S. strategy “is to ensure that the economic costs for Russia are severe and sustainable, as well as to continue supporting Ukraine militarily in its effort to inflict as many defeats on Russia as possible.” Long before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, since 2014, the United States has—through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative of the U.S. Department of Defense--spent more than $19 billion in providing training and equipment to the Ukrainian military ($17.6 billion since Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022). The total annual budget of the United Nations for 2022 is $3.12 billion, far less than the amount spent by the U.S. on Ukraine today. The arming of Ukraine, the statements about weakening Russia by senior officials of the U.S. government, and the refusal to initiate any kind of arms control negotiations prolong a war that is ugly and unnecessary. Ukraine Is Not in Iowa Ukraine and Russia are neighbors. You cannot change the geographical location of Ukraine and move it to Iowa in the United States. This means that Ukraine and Russia have to come to an agreement and find a solution to end the conflict between them. In 2019, Volodymyr Zelenskyy won by a landslide (73 percent) in the Ukrainian presidential election against Petro Poroshenko, the preferred candidate of the West. “We will not be able to avoid negotiations between Russia and Ukraine,” Zelenskyy said on a TV panel, “Pravo Na Vladu,” TSN news service reported, before he became president. In December 2019, Zelenskyy and Putin met in Paris, alongside then-Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel and France’s President Emmanuel Macron (known as the “Normandy Four”). This initiative was driven by Macron and Merkel. As early as 2019, France’s President Emmanuel Macron argued that it was time for Europe to “rethink… our relationship with Russia” because “pushing Russia away from Europe is a profound strategic error.” In March 2020, Zelenskyy said that he and Putin could work out an agreement within a year based on the Minsk II agreements of February 2015. “There are points in Minsk. If we move them around a bit, then what bad can that lead to? As soon as there are no people with weapons, the shooting will stop. That’s important,” Zelenskyy told the Guardian. In a December 2019 press conference, Putin said, “there is nothing more important than the Minsk Agreements.” At this point, Putin said that all he expected was that the Donbas region would be given special status in the Ukrainian Constitution, and during the time of the expected Ukraine-Russia April 2020 meeting, the troops on both sides would have pulled back and agreed to “disengagement along the entire contact line.” Role of Macron It was clear to Macron by 2020 that the point of the negotiations was about more than just Minsk and Ukraine; it was about the creation of a “new security architecture” that did not isolate Russia—and was also not subservient to Washington. Macron developed these points in February 2021 in two directions and spoke about them during his interview with the Atlantic Council (a U.S. think tank). First, he said that NATO has “pushed our borders as far as possible to the eastern side,” but NATO’s expansion has “not succeeded in reducing the conflicts and threats there.” NATO’s eastward expansion, he made clear, was not going to increase Europe’s security. Second, Macron said that the U.S. unilateral withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019—and Russia’s mirroring that—leaves Europe unprotected “against these Russian missiles.” He further said, “As a European, I want to open a discussion between the European Union and Russia.” Such a discussion would pioneer a post-Cold War understanding of security, which would leave the United States out of the conversation with Russia. None of these proposals from Macron could advance, not only because of hesitancy in Russia but also principally because they were not seen favorably by Washington. Confusion existed about whether U.S. President Joe Biden would be welcomed into the Normandy Four. In late 2020, Zelenskyy said he wanted Biden at the table, but a year later it became clear that Russia was not interested in having the United States be part of the Normandy Four. Putin said that the Normandy Four was “self-sufficient.” Biden, meanwhile, chose to intensify threats and sanctions against Russia based on the claims of Kremlin interference in the United States 2016 and 2018 elections. By December 2021, there was no proper reciprocal dialogue between Biden and Putin. Putin told Finnish President Sauli Niinistö that there was a “need to immediately launch negotiations with the United States and NATO” on security guarantees. In a video call between Biden and Putin on December 7, 2021, the Kremlin told the U.S. president that “Russia is seriously interested in obtaining reliable, legally fixed guarantees that rule out NATO expansion eastward and the deployment of offensive strike weapons systems in states adjacent to Russia.” No such guarantee was forthcoming from Washington. The talks fizzled out. The record shows that Washington rejected Macron’s initiatives as well as entreaties from Putin and Zelenskyy to resolve issues through diplomatic dialogue. Up to four days before the Russian invasion, Macron continued his efforts to prevent an escalation of the conflict. By then, the appetite in Moscow for negotiations had dwindled, and Putin rejected Macron’s efforts. An independent European foreign policy was simply not possible (as Macron had suggested and as the former leader of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev had proposed in 1989 while talking about his vision for a “common European home” that would stretch from northern Asia to Europe). Nor was an agreement with Russia feasible if it meant that Russian concerns were to be taken seriously by the West. Ukrainians have been paying a terrible price for the failure of ensuring sensible and reasonable negotiations from 2014 to February 2022—which could have prevented the invasion by Russia in the first place, and once the war started, could have led to the end of this war. All wars end in negotiations, but these negotiations to end wars should be permitted to restart. AuthorVijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is the chief editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including "The Darker Nations" and "The Poorer Nations." His latest book is "Washington Bullets," with an introduction by Evo Morales Ayma. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives November 2022 With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the West – led by the American empire – has tried to press for a belligerent solution to the crisis, speaking to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s regime only through the language of sanctions and weapons. Refusing to address Moscow’s security concerns regarding the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the core capitalist countries of the Global North have chosen to portray Putin’s government as an ideological pariah that needs to be excluded from the international diplomatic community. This has entailed characterizing the Russian ruling dispensation as “fascist” – an accusation that instantly delegitimizes negotiations with the entity that carries that label. Western denunciations of Russian fascism are incorrect because they fail to understand the complexity of Putin’s regime. After the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Russia entered a severe economic crisis. Boris Yeltsin – the man who conducted a coup against the Soviet Union – became the favored puppet of the US and sold off the wealth of his country at ridiculously low prices to a group of oligarchic cronies. The legalized robbery of the nation’s social wealth reversed many of the gains of the USSR. Life expectancy rates dropped, Russian military power suffered drastic setbacks, and economic sovereignty got compromised through privatization, which converted Russia into a playground for Western capitalists. Yeltsin’s brutal destruction of the Soviet Union was domestically propped by two different factions of the ruling class. State capitalists (insiders) controlled large-scale industry – natural resources, energy, metallurgy, engineering – while private capitalists (outsiders) dominated banking, consumer goods, the media. In “Russia Without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War,” Tony Wood notes: “One group tended to own physical assets, the other financial wealth. For much of the 1990s, economic conditions favored the ‘outsiders’: industrial production was crippled, and those with access to large reserves of cash had the edge.” On top of economic advantages, the outsiders benefitted from the political changes that accompanied the downfall of the USSR. In the words of Wood: “Insiders, as their name suggests, tended to be better connected to the regional and national government apparatus, often through informal ties forged in the Soviet era.” The dissolution of the Soviet Union unleashed chaos in the state bureaucracy and disrupted the connections of the insiders. This allowed the outsiders to penetrate state institutions and forge business links. However, the politico-economic dominance began to falter with the rouble crash and debt default of 1998. The crash meant: a) the disappearance of the economic privileges of the outsiders who owned financial wealth; and b) currency devaluation, which improved Russian domestic production by making imports more expensive, strengthening the insiders who had assets in manufacturing, agriculture, food processing and distribution, etc. “The surge in raw materials prices after 1999,” writes Wood, “hugely accelerated the reshaping of the Russian elite that began with the rouble crash. In 1997, only a few of the top ten oligarchs had interests outside banking or the media. After the turn of the century, almost all of the top ten owed their wealth to metals or mineral resources”. With the revival of domestic industry and the increase in energy prices, the balance tilted in favor of the insiders, who used their growing economic power to prevent private capitalist interests from accessing state power. Putin represented this shift in class forces, pushing forward a state capitalist agenda that involved recentralizing power in the state and curtailing the political ambitions of outsiders. Unlike Yeltsin’s compradorized system, this kind of statist neoliberalism possesses political and administrative coherence as it is based on the existence of a solid bureaucracy whose consolidated institutional capacity allows it to gain profit from exploitative ventures in extractive sectors. The relative stability of this arrangement has meant that Putin’s system has a margin of diplomatic leeway in its relations with the West. This leeway has been utilized by Russian rulers to make the country a regional power. In this way, geopolitical power has been used as a way to deal with citizens’ anti-neoliberal sentiments and restore their national pride. As Ilya Budraitskis comments, “Putin’s rule… [is a] kind of amalgamation of neo-liberal practices and pro-market ideas with the spirit of the so-called patriotic opposition to this market transformation.” Putin’s geopolitical project of reinstating Russia’s international position is driven by the following logic: “to survive, Russia can only be a strong state, that is, a great power abroad, and a quite uncontested regime at home. For that, it needs law and order, unity more than diversity, respect from foreign countries and its own citizens, and a renewed sense of honor and dignity.” These ideological imperatives are satisfied by “anti-Western and antiliberal attitudes, Soviet nostalgia, and a classic, state-centric vision of Russia.” As is evident, Russia does not have fascism. Instead, it pragmatically operates according to multiple ideologies that can challenge the legitimacy of the US-led world order and thus, help combat imperialist attacks against Russia. Western observers have accused Russia of being fascist because they overemphasize the conservative and authoritarian elements that compose Putinism. What they overlook is the fact that these ideologies are said to be against the excessive liberalism and globalism of the West. Thus, what matters for Putin is a sovereignist position against the West, one that uses patriotism against an interventionist Western liberal order. The hegemony of patriotic opposition to imperialism means that the normative core of Russian ideology is not genocidal hatred against an Other and a will to create a new xenophobic culture, all of which are essential ingredients of fascism. Rather, the Putinist worldview utilizes notions of Russian uniqueness – whether it be in the form of national history and culture, illiberalism, or Soviet nostalgia – to undermine the current West-centric world system. Far from resulting in fascism, the perspective of a distinct Russian civilization has shown itself capable of acknowledging the country’s multinational and multiconfessional character. The Duma has repeatedly rejected bills that ask “for the recognition of ethnic Russians as having rights superior to those of citizens belonging to ethnic minorities”. Further, on the international front, the Putinist narrative is accepts “a Herderian perception of the world, according to which each “civilization” or “culture” represents the diversity of humanity and should be celebrated for its uniqueness—hence the active role played by Moscow in any international project based on the notion of a “dialogue of civilizations.”” To conclude, Putin’s geopolitical opposition to the American empire – materially rooted in neoliberal statism – has given rise not to fascism, but to Realpolitik that deploys ideological plurality to contest the West’s hegemonic narratives. AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. 3/28/2021 Biden's 'Killer' Comment About Putin Reflects Obsolete Foreign Policy. By: John WojcikRead NowBiden, at the time vice president, right, speaks to Putin, then the Russian Prime Minister, second left, during a meeting in Moscow, March 10, 2011. The two are now face each other as presidents of their respective countries. | Alexander Zemlianichenko / AP I want to start this critique of Biden’s developing foreign policy by stating clearly and unequivocally that his $1.9 trillion rescue plan deserves total support from everyone in our country. It is nothing less than a dramatic disavowal of the right-wing era launched by Ronald Reagan some 40 years ago. Although Biden deserves praise for his domestic policy so far, his characterization on national television of Russian President Vladimir Putin as a “killer” was just another indication of what is, unfortunately, turning out to be a dangerous trend in the foreign policy he is pursuing. While his domestic policy radically departs from what we have seen in the U.S. over the last 40 years his, foreign policy—executed by stalwart representatives of the old establishment—is failed business as usual. And the unfortunate reality is that a continuation of the policy of military domination of the entire world will sooner or later require turning away from progressive domestic priorities. As Biden begins his presidency, we are in a different and new world, one that did not exist in the Reagan-Bush-Clinton days of neoliberalism. The planet is in a very real climate emergency and is reeling under a global pandemic. Super recessions and depressions are crippling many countries economically. The wealth gap is growing day by day, and corruption in government, which has always been a problem, is even worse now, with scandals happening in almost every country in the world. Also worse than ever are the attacks on democracy happening in nations that have previously prided themselves as beacons of freedom. Solutions for these unprecedented problems will require unprecedented international cooperation. This is not the time then for the president of the United States to be calling the president of Russia, the second-largest nuclear power on earth, a “killer.” There are indeed plenty of killers running plenty of countries these days, as there have been in the past, including in our own. But the crises of today require cooperation between the two largest nuclear powers. Calling Putin a “killer,” however, reflects some real and far more dangerous trends in U.S. foreign policy. It reflects the control still being exercised by the old foreign policy establishment that played such a big role in bringing us the world-wide mess we have today. The U.S., thanks to the old foreign policy establishment, has almost 800 military facilities around the world. The new domestic and worldwide realities of today require dismantling of that network of bases. That will require changing the thinking about what constitutes national security. That shift will have to be as big if not bigger than the change we have seen from the Biden administration when it comes to domestic policy. For starters, the U.S. will have to stop military adventures around the globe, including the confrontational ones on Russia’s borders. Calling Russia’s leader a “killer” while the U.S. threatens that country with our troops along its frontiers is hardly helpful to the cause of re-ordering our priorities. Likewise, U.S. military confrontation with China in the South China Sea will not be at all conducive to the necessary reordering of priorities. There is no real indication yet that Biden is moving in the direction of ending confrontation with either Russia or China. In Afghanistan, the United States has been at war for more than 20 years. Trillions of dollars have been spent on that war. Many have died. Biden is now signaling U.S. troops will stay there beyond the date which Trump had claimed American forces would pull out. What amounts to institutionalized warfare, it seems, is something Biden is willing to continue. There is no hope of getting back what has been lost in Afghanistan. The only prudent course is to get U.S. troops out of there. Biden, during his campaign for the White House, promised to revive the Iran nuclear deal he helped negotiate when he was vice president. He promised to also bring back the constitutional role of Congress in declaring war. But he instead ordered the bombing—over the objection of Democratic senators who called it a violation of the War Powers Act—of what he said was an Iranian-backed outpost in Syria. In addition, he has delayed removal of 900 U.S. troops who are uninvited occupiers in Syria. He is maintaining troops in a sovereign country against its will and has ordered a bombing in that same country’s territory. Biden said he is reviewing our drone policies, but so far, that review has resulted in more focused targeting and no indication that use of killer drones will be ended. He is continuing U.S. support for regime change by continuing inhumane sanctions against Venezuela—sanctions clearly intended to overthrow its government. To no avail, the UN has called on the U.S. to end its cruel blockade tactics that deny medicine and food to the Venezuelan people. And back to Russia, Biden is ratcheting up dangerous confrontation with that country. In the next few weeks, Biden said, in answer to a question on national television, that “we will see” how he retaliates for last year’s SolarWinds hack of U.S. cyberinfrastructure—for which Russia was allegedly responsible. Knowledgeable sources say the administration will approve still more sanctions on Russia and clandestine cyber actions against Russian state institutions. Such an escalation is likely to trigger more and worse cyberattacks by both sides. Is that what we really want right now? In the long term, that will do no good at all for either the American or the Russian people. On China, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken has called relations with China “the biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century,” with the administration making a show of not just confronting China economically but also militarily in the South China Sea. U.S. naval maneuvers there continue. As the administration does this, the Republicans put forward continued accusations in public congressional hearings that the “Chinese Communist Party” is responsible for both the pandemic and for economic problems in the U.S. resulting from the pandemic. Such anti-China rhetoric inflames the international situation while also fueling domestic anti-Asian hate crimes and attacks. The United States cannot focus on and help solve the climate crisis, the pandemic, and worldwide economic disasters, including inequality and the wealth gap, by continuing institutionalized warfare, regime change, threats of military action, and maintaining 800 bases around the world. No one pretends that the foreign policy of the U.S. can or will be radically changed overnight. The hope is there, however, that based on what we see happening in domestic policy, the Biden administration may yet begin to move in a better direction when it comes to foreign affairs. You can start, Mr. President, by not grandstanding against the Russians. That’s so old, and it gets us nowhere. AuthorJohn Wojcik is Editor-in-Chief of People's World. He joined the staff as Labor Editor in May 2007 after working as a union meat cutter in northern New Jersey. There, he served as a shop steward, as a member of a UFCW contract negotiating committee, and as an activist in the union's campaign to win public support for Wal-Mart workers. In the 1970s and '80s he was a political action reporter for the Daily World, this newspaper's predecessor, and was active in electoral politics in Brooklyn, New York. Republished from Peoples World.

As with all op-eds published by People’s World, this article reflects the opinions of its author. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed