|

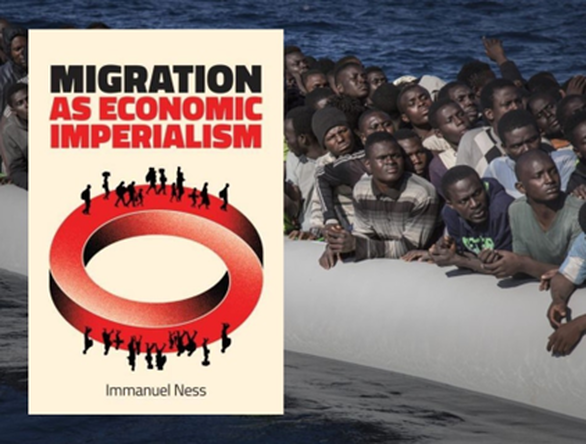

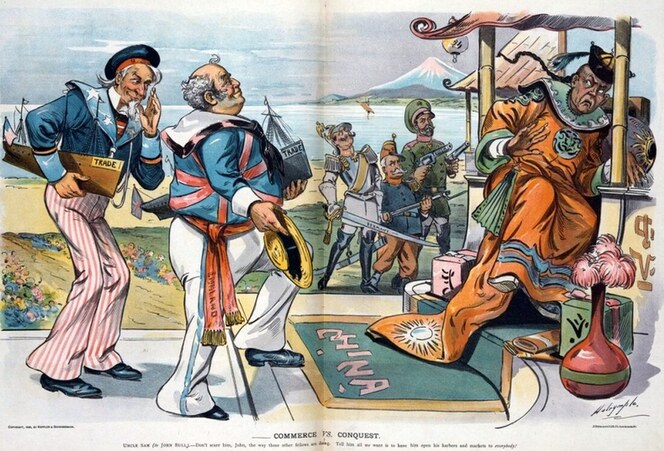

9/30/2023 Review of Immanuel Ness’s Migration as Economic Imperialism. By: Carlos L. GarridoRead NowThis review is adapted from the book launch presentation the author did for Immanuel Ness’s Migration as Economic Imperialism, which you can purchase HERE. The traditional Marxist critique of ideology has understood both the functional and epistemological dimensions of bourgeois ideologue’s claims. This tradition has always emphasized how ideas are both conditioned by the historical conjunctures and class positions of the people and institutions that materially embody them, but also – and equally important – how, under class societies, the economically dominant class, in whose control the rest of the political, juridical, and ideological institutions are under, has to necessarily distort the world’s understanding of itself so that the vast majority of people, whose class interests are diametrically opposed to theirs, can consent to this topsy turvy image of the world. As Marx and Engels noted early on in their theoretical development, If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process. This structurally necessary ideological inversion will later be labeled by Engels false consciousness, a condition where the people are unaware of the “real driving forces which move [them], [instead] imagin[ing] false or apparent driving forces.” This prevents bourgeois ideologues from properly understanding the world – it subdues their ability to obtain truth in their work. However, this is far from being only a question of errors in thinking, that is, the problem of ideological false consciousness, contrary to popular belief and those of the post-modernized Western “Marxist” specialists, is far from being merely one of consciousness. The inverted character of ideologue’s ideas is a reflection of an objective social order that requires its inhabitants to think of it in deliberately inverted ways. In short: the ‘error in thinking’ is an objective necessity for our social order, a social order that requires the generalization of mistaken views of itself for its own reproduction. The conventional bourgeois-imperialist narratives on migration and migrant labor, a phenomenon which affects around 3 billion people (approximately 40% of the world), is filled with these ideological inversions. Immanuel Ness’s book, Migration as Economic Imperialism, does an exceptional job at exposing how these ideas emerge of out the capitalist-imperialist system (and not out of some mythical disinterested and bias-free scientific observers). He shows us how these ideas distort reality, providing us with an upside-down image of the real world. And finally, he shows us who benefits, i.e., what class and social system is upheld by the systematization of these ideological contortions. The book is, in short, a quintessential example of what Marxist scholars should be doing in the battle of ideas: exposing the hollow falsity of bourgeois narratives, and replacing these with the truth – which, as we know well, is always on the side of the revolutionaries. While this last point might seem swaggering, it is not our fault, as Che Guevara is often attributed to have said, that reality is Marxist. The conventional imperialist narrative on migrant workers holds that they benefit the global economy, the global north countries of destination, and the global south countries of origins. Through remittances and the skills migrant workers obtain in the global north, so the imperialist narrative goes, they can help develop their countries of origin. Remittances are painted as “a leading form of economic development for poor countries” by International Development Agencies, the World Bank, and other imperialist institutions. After the migration boom of the 1990s that followed the overthrow of the USSR, the increased flow of remittances led bourgeois specialists to hold that this was a far more preferrable alternative to the old school ‘foreign aid’ that kept poor countries dependent on rich ones (the system that devised mechanisms of debt trapping and structural adjustment programs that kept global south countries poor and indebted, of course, was never questioned). In addition to remittances, the conventional imperialist narratives held that a stratum of higher skilled migrant workers were capable of developing new skills in the global north. These skills, so the myth goes, are taken back to the origin country and used to fuel their development and fight poverty. Are these narratives true? Do they actually correspond to the reality they attempt to explain? As you could’ve guessed it, they are about as true as any of the other capitalist myths. Which means, from the standpoint of a comprehensive analysis of the world as it actually exists, these claims are not true at all. In fact, their conclusions turn reality upside down; as the Athenian oligarchs once wrongly accused Socrates of doing, they are the ones that make “the worst appear the better cause.” They make migration, which benefits almost exclusively the elite of the imperialist countries, appear as a beneficial phenomenon for those poor souls forced into it by the conditions their countries have been subjected to after centuries of imperialist plunder and colonial and neocolonial domination. In reality, as Manny eloquently demonstrates, “remittances do not improve the standard of living for most inhabitants living in poor countries and do contribute to economic imbalances which engender higher levels of crime and violence.” “Remittances themselves,” as Manny shows, contribute to the erosion of the agrarian sector in southern economies as they constitute a form of rent for many residents in origin countries who are dependent on the continuing flow of remittances… [an] unreliable source of income.” Additionally, even when certain migrant workers obtain new skills in the global north, many of them do not return home – skilled migrant workers, as Manny notes, “are more likely to be provided with legal status than low-wage workers.” This leads to what some scholars have called ‘brain drain,’ the systematic flight of skilled workers, scientists, and technicians from their countries of origin in the global south (where they often got their education) to the countries of the imperialist global north. However, even when these skilled workers do go back, Manny demonstrates that they often end up working in “niche economies which do not contribute to improving the lives of most residents there but are directed to building networks with international business … that benefit a small fraction of elites as the majority of inhabitants remain mired in poverty.” So, for the imperialized countries of origin, where exactly are the benefits of migration? Besides the outliers in the elite that are benefited, the reality is that there are none. “If migration were beneficial to development [in countries of origin],” as Manny notes, “then countries with high migration would not be suffering the highest poverty rates, or would at least be seeing improvements outstripping those countries that were not following a migration-development strategy.” The evidence shows that the opposite of the conventional migration-development paradigm is true – migration helps to keep poor countries poor while enriching rich countries with a pool of cheap labor that they can superexploit. “The ten-leading remittance-receiving nations,” for instance, “are amongst the poorest states in the world.” “The primary dynamic of migration,” as Manny shows, “is rooted in the political economy of imperialism, which subordinates poor regions of the Global South.” Contemporary migration is, therefore, a product and central component of imperialism. It provides for imperialist countries, whose rates of profits with their national working class have been on a steady decline, a cheap pool of labor to superexploit. These are workers, many undocumented, who are forced to break with their families by the hundreds of millions in search for jobs that pay them pennies on the dollar of the already exploited global north workers. They frequently take up the most dangerous jobs and are forced to do these under the most precarious conditions, with very little bargaining power. They are often the recipients of xenophobic attacks and derogatory racist remarks, a phenomenon produced by the elite of the global north to convince their native workers (themselves struggling to get by), that their enemy is the migrant, not their boss. An interesting paradox arises here: while migrant workers have become an indispensable component of the imperialist economies for which they provide a cheap pool of labor to superexploit, these same workers are treated with the utmost expendability – evidenced in their working conditions and racist treatment. This is a phenomenon some scholars have called the ‘dialectics of superfluity,’ where human life and labor becomes simultaneously indispensable and expendable for capitalism. It is a condition that, while general in the working class, is intensified in migrant workers and oppressed peoples. Things don’t have to be this way. In fact, it is impossible for them to continue this way forever. The world and everything in it are in a constant state of flux, where all is interconnected to all and contradiction functions as the engine of historical motion. These objective contradictions in the global capitalist-imperialist economy contain the kernels for their own supersession. The interests of migrant workers and workers in the global north are the same. Both are fighting against the same global capitalist elite. It is this same elite that exploits and oppresses them both, even if it does it to one with more intensity than the other. The interests of workers of all countries, migrant or not, are found in uniting with their class against the parasitic rulers of the world – those who destroy humanity in their pursuit of profit. As time passes and these contradictions intensify, we are seeing workers coming together to fight. We are seeing the embryonic development of class consciousness – and sooner or later – we will see in mass the moderate demands James Connolly heralded in 1907: “We only want the earth.” Watch the book launch event for Migration as Economic Imperialism below: Author Carlos L. Garrido is a philosophy teacher at Southern Illinois University, Director at the Midwestern Marx Institute, and author of The Purity Fetish and the Crisis of Western Marxism (2023), Marxism and the Dialectical Materialist Worldview (2022), and Hegel, Marxism, and Dialectics (Forthcoming 2024). Archives September 2023

6 Comments

The 19th Century was a very significant period, especially in the field of Philosophy. This era laid the foundations for Modern Philosophy and shaped the course of this discipline for centuries to come. It is also the time when Renaissance Modernism matured into its final stages(at least in Western Europe where Feudalism was being completely dismantled) since religion was dethroned from its position as the central ideological doctrine of society, it no longer formed the backbone of the hegemony of the ruling classes. Religion wasn't the dominant worldview anymore, it had collapsed by now. But radical change is always accompanied by deep crises. Western Europe was walking on the path of tearing apart the religious worldview of the Dark Ages in hopes of reaching the destination of enlightenment but what they were unaware of was the fact that to reach their destination they would have to overcome the hurdle of crisis. A crisis which awaited them eagerly— The Crisis of Nihilism. It is this crisis that we shall explore in this article. We will begin our journey from the feudal times to understand the historical context in which Nihilism arose and then move on to the significant developments in Philosophy throughout the Renaissance period and the rise of Modernist Philosophy, which will then enable us to understand the crisis of Nihilism in its totality. But we shall not stop our investigation there. I would like to dedicate a section completely to a phenomenon I call "Capitalist Nihilism", where we explore how Capital and Capitalism have added fuel to the fire of Nihilism that burns in the minds of working masses of the world. FEUDALISM, IDEOLOGY AND GOD Human civilisation has organised itself in many ways from time to time and Feudalism is one such form of organisation. As Gramsci proved through his work, no society has ever been able to maintain itself without an ideology of its own, an ideology that is dominant within the society. The hegemonic ideology. But one society can adopt multiple 'hegemonic ideologies', there will be some common traits or themes within these ideologies. Eg; Liberalism and Fascism are two 'hegemonic ideologies' of Capitalism. They have their differences but they have quite some common traits too, like Protection of the Right to Private Property, using State power to serve Corporates and of course preserving capitalism at any cost. These themes will be shared by any and all variants of Liberalism, Fascism or any ideology of Capitalism. Every era of human history, as stated earlier, has some hegemonic ideological themes which are unique to that era itself. These themes are seen as principles or norms which should dictate our social organisation and also our moral or ethical positions. It is needless to say that these ideologies strive to maintain a particular structure of society, which is often exploitative in nature, and thus will always serve the interests of the ruling class. Feudalism too had its own ideology— Religion. Religion, in feudal times, provided the masses with a 'meaning'. The people had a role to play in the grand scheme of things and that role could only be fulfilled if they kept following the word of God (of the ruling classes actually. The privilege of hindsight allows us to understand that God was really only a messenger of the ruling classes and not the other way around.). Their actions, thoughts, happiness and even their suffering had an objective, they weren't working for the sake of working; they were working so that they could help God fulfill his plan for the world. The Abrahamic Tradition posits that there would be a 'Judgement Day' where people will either get into heaven or into hell. Thus under the influence of these traditions, people would work or live to get into heaven. The Indic Traditions of Hinduism(some streams of it) and Buddhism on the other hand, don't subscribe to the concept of a heaven-hell dichotomy. Rather these religions advocated the concept of rebirth. Hinduism suggested that if one remains pure and virtuous in one life then they'll be reborn as a "Brahman" or a Savarna but failing to do so will result in one's rebirth into an Avarna family(an obvious ploy to justify the inhumane Caste System). Buddhists, on the other hand, put forward a theory in which the end point of liberation was Moksha or Enlightenment which would end the cycle of rebirth.[1] The objective of these worldviews is exposed not only by their unscientific approach to the question of life and death but also by their egocentric nature. Humanity and human society is always placed at the center of the Universe in these theories. The whole Universe revolves around humanity. It is our actions that will bring about both the apocalypse and the salvation of this vast universe. But, as we know, change is inevitable and change was long overdue in these societies. So soon change would be unleashed upon them. THE BEAST OF MODERNISM This universal objective of human life or the meaning of life were a result of the God centric morality and the religious worldview but as modernism came into full swing, this worldview began falling apart and the meaning of life along with it. The 19th Century was witness to the publication of texts which shook the very foundations of the Religious Worldview like an explosion. Some of these works include:

Modernism had completely destroyed the religious vestiges of the Feudal times. The God serving meaning of life being dissolved with it. But this wouldn't end here, for now that the Beast of Modernism was unleashed, it would wreak havoc. This beast, hungry for truth and enlightenment, would tear apart the Religious Worldview to satiate its hunger. It would feast on the 'objective meaning of life'. It would create— chaos. THE CHAOTIC DEATH OF GOD "Whither is God?" he cried; "I will tell you. We have killed him---you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down? Are we not straying, as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Isn't night continually closing in on us? Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning? Do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition? Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him." —The Gay Science, Friedrich Nietzsche This passage is perhaps the most accurate literary representation of the ideological, philosophical and subsequently moral dilemma that modernism has created. Nietzsche was not particularly referring to the literal death of a divine entity but rather the death of Feudal Values and Worldviews. Till now, God formed the basis of our understanding of reality, especially, our place in it. God gave people a goal and their lives a meaning. Society's whole perspective of reality was now crumbling under the weight of the mountain of rationality unleashed by humanity's very own hunger for the truth. This is the crisis of Nihilism, the crisis of accepting that reality is not Human-centric. The very idea that humans and human society are just a mere coincidental(if not accidental) product of Universal Contradictions and not the masterpiece of some divine entity, the idea that life has no meaning whatsoever, the idea that any and everything we do is useless in the longest run are the ideas that form the basis of the Philosophy of Nihilism. Humanity had to come to terms with the fact that it or anything it did is not just 'not special', but also pointless; it did not serve any higher power or any grand scheme. This pointlessness, this feeling of helplessness, this generated the crisis of Nihilism. The Death of God unleashed chaos in the realm of human knowledge, chaos that was reflective of the socio-political and economic landscape of Europe. This period in European history is marked with Republican Revolutions which were challenging the Feudal Political systems at the time but had not given shape to Liberal Democracies yet. This political chaos of Europe is reflected in the chaos of the Modernist Worldview. But that chaos too subsided. We found a new god to worship— Capital. Early 20th Century saw the complete rise of Liberalism, which had taken root as the primary ideology of the world during the 20s. We now had a system of Morality, Ethics and Values; a new god which influenced us everyday; a new entity that we submitted ourselves to— Capital. But even today, after the establishment and reestablishment of Capital (Rise Neo-Liberalism in the 90s) as our God, Nihilism is an ideology which can be relatable to many people. But why? The answer lies within Modernist Thought itself. ALIENATION AND NIHILISM Alienation as a concept has been part of the central subtexts of Karl Marx's works, even though Marx's approach to Alienation has changed multiple times. His original approach to Alienation was Idealist in nature but slowly he adopted a more Materialist approach. But it is not his conception of Alienation that concerns us today, but rather how it can harbour Nihilistic sentiments within us. Alienation or, in Hegelian terms, Estrangement, refers to a phenomenon where humans are detached from their labour and that gives birth to mental health crises. Think of it like this; we as humans spend at least one-third of our day at our workplace working and in the end we are completely detached from the product of the labour, we have no idea who will use the final product, what for or how and often we can't even afford that final product(Alienation from the Product of Labour). But it doesn't end here, it should also be noted that we as workers don't have any say upon the process of production or how we work(Alienation from the process of Labour). Everything from the methodology to the timings of the workplace is directly or indirectly controlled by the capitalists while we are reduced to being cogs in a machine who don't know what they're doing or don't even have any say in the process. This is our central concern. Let us take some examples, consider an Industrial Worker and a White Collar Worker. Both of them spend their time away working and generating value for the Capitalists with no relationship with their product or the production process. For 8 hours or more(it's usually more than 8 hours) they are just acting as cogs in a machine, they are not human, they are indulging in meaningless mechanical work. Work which leaves them so tired that it is not even possible to do or think about anything else, they can't commit to anything for they have been sucked dry by mechanical labour requirements. There is no space left in your life for hobbies, relationships or general chores other than your job; your job consumes everything like the Blob from The Blob. There's nothing left of them. The White Collar worker escapes this by hiring househelp etc.(their position as a Labour Aristocrat can also make things easier for them) while the Industrial Worker has no options(other than expropriation of domestic labour through marriage if he's a man). Thus the only thing that dominates their life and activities is a Job which they, reasonably, find meaningless. As we've understood the relationship a worker has with their job, one of meaninglessness and parasitical labour, we can now say that if a person with such a job relates to the Philosophy or Crisis of Nihilism should we be surprised? Now, many find solace in the 'objective' of blindly earning money, accepting Capital as your true God but even that cannot save them from the inevitable and unavoidable devastation of Alienation. These people cannot be 'happy' or 'content' even if they live luxuriously, not because they're greedy, but because they're estranged, they're alienated. They're hollow from the inside and try to fill the void left by the appropriation of Surplus Labour with tacky consumerism, supplementing their physical attitudes, overconsumption or binge-consumption and recreational substances. But at some point of time, all else fails, and reality hits us as we as humans once again face the crisis of our virtues and values falling apart like stale bread, we are once again hit with the Crisis of Nihilism— The Nihilism of Capital. Marx perfectly sums up the the estranged Nihilism that Capital gives birth to when he wrote in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 The less you eat, drink, buy books, go to the theatre or to balls, or to the pub, and the less you think, love, theorize, sing, paint, fence, etc., the more you will be able to save and the greater will become your treasure which neither moth nor rust will corrupt—your capital. The less you are, the less you express your life, the more you have, the greater is your alienated life and the greater is the saving of your alienated being. Another accurate representation of this condition can be found in the following quote from Capital Vol. I: Capital is dead labor, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks. But when, at the end of the day, the worker comes home completely exhausted and distraught, his ability to work or do anything completely sucked out, a part of his conscious self hollowed out by his job; why does the worker question all of existence instead of questioning the form of existence? NIHILISM AND CAPITALIST REALISM If or whenever we draw a comparison between feudal and capitalist systems of hegemony, the first and foremost difference that comes to mind is the ability of capitalist hegemony to shape our worldview. This ability is also what Mark Fisher studies in his book "Capitalist Realism". Fisher notes that capitalism or capitalist hegemony has become so powerful, so deep-rooted in our minds that it has transcended the form of a system of hegemony— instead it has turned into a homogeneous cultural mindset that restricts or destroys our very ability to imagine and reason beyond the limitations of the capitalist framework. This is what Fisher has termed Capitalist Realism; the conception that capitalism is the only viable or efficient system of social organisation rendering any other alternative unimaginable or utopian. This idea became the predominant notion of the Post-Soviet world when the fall of the Soviet Union was used as a justification and the exploitative nature of the capitalist mode of production wasn't just offshored but rather projected as an inherent ill of the human species itself; exploitation was attributed to "human nature" and capitalism was propounded to be the only system with the majestic ability to rationalise or control our greedy exploitative nature. The ideological apparatuses of the State and the bourgeoisie created an "eternal present" where capitalism remained dominant without any challenge. This phenomenon was best embodied in the phrase "it is easier to imagine the end of the world than imagining the end of capitalism" and "capitalism is human nature". At this point in history, the difference between capitalist and feudal hegemonies wasn't just quantitative but also qualitative. Capitalist hegemony has turned into the demon that takes over our complete consciousness by whispering at the back of our heads. The effects of this phenomenon are felt every moment. One of the best examples of this would be the popular discourse around Climate Change and Environmental Damage. It is capitalism and its profit prioritisation policy that has brought us to the very brink of extinction yet whenever popular discourse regarding the climate catastrophe and methods of prevention are discussed they are always discussed, not just within the boundaries of capitalism, but with people's consumption patterns at the center. According to such discourse, people using plastic straws is more concerning than only a hundred companies being responsible for 70% of the world's carbon emissions or the fossil fuel industry actively discouraging Solar Power research and facilities because it is "not profitable". Capitalism is about to destroy the planet and yet we cannot imagine a planet without it. It is easier for us to imagine the end of the world through a climate catastrophe than to imagine the end of Capitalism, that is Capitalist Realism at its finest. But how is the philosophy of Nihilism related to Capitalist Realism? Well, I would argue that Nihilism only appears to be a reasonably radical philosophical thought because of Capitalist Realism. If we consider the original nihilists like Max Stirner, they obviously rejected capitalism alongside all other social systems but that was not enough. Philosophies don't exist in a vacuum, they exist within the ideological framework of society and thus, much like society itself, ideologies have their own dominant sections and subservient sections. Any ideological or philosophical thought must interact with the hegemonic ideology of society and this interaction can manifest in one of two ways— either the thought is appropriated and absorbed within the hegemonic ideological fold or the thought stands in staunch opposition to the hegemonic ideology. Nihilism, while rejecting capitalism, never staunchly opposed its exploitative nature and thus it was, eventually, inducted into the capitalist fold. Nihilism benefits from the mass's inability to imagine a life outside of capitalism. The masses experience the exploitation of Capital on daily basis and truly understand that this system is not just, they also understand that their labour is being, in a way, wasted on acquiring profits for the capitalists, they realise that their whole being is being consumed by capital itself and they are being reduced to zombies but still they cannot imagine a life outside of capitalism. This exploitation, this meaninglessness or lack of purpose seems natural to them. So the masses, unable to imagine a life beyond capitalism, beyond working day in and day out without a set purpose, accept this slow death of the human within them as the one true way of living their life and end up rejecting life itself. The only 'life' they've ever known and the only purpose they've ever had is getting a job and working, the only life they have is providing their labour to capitalists and that is not a life worth living. Hence it's obvious that they've rejected life itself. But if for a second, the lens of Capitalist Realism were to be removed, Nihilism were to be removed, what would we see? Capitalism for the all consuming hellspawn it is. Thus we can conclude that Nihilism has been inducted into the fold of capitalist ideology, a philosophical thought, that although seems like a rebellious ideology that can liberate us but truly it only gaslights us by projecting the ills of capitalist life on all of human existence as a whole. As the colour of Capitalist Realism fades from our worldview, we will find the radical shade of Nihilism also fading away. The ability of Capitalism to project its worst qualities upon us, with barely anyone noticing, to term our very existence as suffering, is the Nihilism that serves Capital, it is— 'The Nihilism of Capital'. References [1] Something I'd like to add too is I don't believe that people are truly so stupid to actually believe every word of their religion. Somewhere they hold on to it because it gives them a purpose, even if it's a twisted one, that helps them make sense of their life and suffering. I also believe that their morality is much more dear to them than their religion and people have shown that they're ready to reform their understanding of religion in order better suit their individual and social morality. Author Marnina Avirup is a Marxist-Leninist writer from West Bengal, India. They write on both international and Indian issues (or their correlation). Most of their work is on Political Theory, Comparative Politics, Political History and Philosophy from a Marxist-Leninist perspective. Archives September 2023 Citing a U.S. official familiar with current intelligence, U.S. journalist Seymour Hersh said that the U.S. intelligence believes that the Ukrainian forces have become demoralized and have no chance of winning, adding that there currently exists no discussion in Kiev or the White House regarding a ceasefire. In a new post on his Substack account, Hersh said, There are significant elements in the American intelligence community, relying on field reports and technical intelligence, who believe that the demoralized Ukraine army has given up on the possibility of overcoming the heavily mined three-tier Russian defense lines and taking the war to Crimea and the four oblasts seized and annexed by Russia. The reality is that Volodymyr Zelensky’s battered army no longer has any chance of a victory. Hersh also noted there is no interest in peace talks. Quoting the official, Hersh continued that Ukraine’s claims of incremental progress in the offensive constitute of “all lies”. The renowned investigative journalist reported last month that the CIA informed U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken that the Ukrainian counteroffensive would not likely yield results. This information, said Hersh, came from a U.S. intelligence official, who stated more specifically, that “the word was getting to him [Blinken] through the Agency [CIA] that the Ukrainian offense was not going to work. It was a show by Zelensky and there were some in the administration who believed his bullshit.” Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky has been calling on his Western allies for months to provide his military with long-range missiles, arguing that this could drastically improve the outcome of the counteroffensive. But before that, it was the anti-air missiles, the advanced offense tanks, heavily armored troop carriers, and the HIMARS system. Ukraine is depleting resources at an unsustainable rate, firing 90,000 artillery rounds per month when the Pentagon is only capable of producing a third of that number, while also losing around 20 percent of NATO-provided weapons–that were either destroyed or damaged–within the first two weeks of the counteroffensive, which saw very limited ground gains since it was launched almost three months ago. Archives September 2023 Commerce vs Conquest – “Uncle Sam (to John Bull) Don’t scare him, John, the way those other fellows are doing. Tell him all we want is to have him open his harbors and markets to everybody!” Political Cartoon from 1898. The conquest of one territory and its population by another power has been a prominent part of much, if not all, of the history of human civilisation. While such conquests appeared to occur even in very early periods of history, conquest reached its various peaks with the emergence of great extensive empires. These occurred especially based on the Eurasian continent, and its close neighbour North Africa. Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Roman, and in Asia, various East Asian based empires, including Chinese, conquered and ruled extensive areas. In Europe, the various small kingdoms raided each other but also engaged in conquest and occupation, including the Vikings of Scandinavia. France and Austria, for example, all held extensive territory and different times, as did Russia. Prior to the 16th century these conquests were constrained by as yet undeveloped means of transportation. Ships still relied to a large extent on rowers to assist sailing and were relatively small. The Romans built stone roads which assisted their expansion. Earlier, Alexander the Great was able to take his army all the way to India. However, the technology was not yet there to sustain global or semi-global empires. By the time naval technology and mapping had begun to enable more extensive exploration by the richer European powers, conquest already had thousands of years of history. That powerful states would wage war to conquer and either occupy or subjugate the populations under other states in other territories was “accepted” as inevitable. “Accepted” needs to go in quotation marks because as inevitable conquest seemed in those times, the targets of conquest always resisted, and the peoples being subjugated regularly rebelled. Be that as it may, nobody among the ruling classes of the day seriously struggled for an end to the practice of conquest – except by securing their own conquests as permanent. The inevitability of the need for conquest was a fundamental part of the hegemonic ideology. It was not until the 20th century that the right to conquest began to be questioned from within the various ruling classes of the imperialist countries. The devastation of World War I gave birth to the League of Nations, one of whose premises was that wars, usually wars of conquest, had to be prevented. Then, out of the devastation, suffering and alienation of the Great Depression arose fascism. Nazi Germany, and later Japan, attempted massive wars of expansion. Germany even tried to conquer both the Soviet Union and Great Britain, as well as West and Eastern Europe and North Africa. Japan tried to conquer Korea, China and Southeast Asia, and also targeted Australia. Out of World War 2 came the United Nations whose Charter and other documents also de-legitimise conquest. That was supposed to end. The world would consist of sovereign nations who would settle differences peacefully – and indeed the very idea of conquest was ruled out. The End of Conquest and its Blind Spot The League of Nations, but especially the United Nations, de-legitimised conquest being any part of the future of humanity. But it also began a process of ending a form of conquest that all the European powers as well as the United Stated and Japan had been guilty of – colonial conquest. From the 16th century onwards, naval technology and science began to allow European powers to send ships, often carrying the new advance in military technology of the cannon, far from their own continent to the Americas, Africa and Asia. Colonial conquest began – piecemeal at first as small local states were subdued – but later larger states and territories were conquered, subdued and sometimes occupied. Two thirds to three quarters of the world were conquered and subjugated by the United Kingdom, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Italy, America, Japan and to a lesser extent Germany. Struggle for freedom from subjugation, that is, for independence from the conquering power, began in the 18th century in South America, where genocide and occupation had produced ruling classes and demographics that promoted the formation of serious pre-national communities. In Asia and Africa, while rebellion was almost constant, political and military movements with strategies to end their state of conquest developed more strongly in the 20th century. Anti-colonial revolutions started to emerge alongside the new, revolutionary processes of nation creation, dissolving or transforming the social formations that had existed under earlier pre-capitalist modes of production. In Asia, most of these anti-colonial revolutions were able to make use of the weaknesses of the European powers and Japan, and even the United States, during and after WW2 to escalate their struggles. But despite the decolonisation mandate of the United Nations, in reality the colonies were a blind spot as regards the illegitimacy of conquest. While the British conceded quickly in India, it took decades of armed resistance and many, many deaths in the British colonies in Africa and Southeast Asia before decolonisation began. The French fought for more than another decade after WW2 to retain their earlier conquests in Indochina and North Africa. And even when the French withdrew from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, the United States intervened with massive military force to prevent the completion of national liberation and social revolution. The Dutch ruling class, despite the formation of the United Nations, sent an army back to the Dutch East Indies far away in Southeast Asia to reconquer their earlier conquests. They even granted amnesty to Dutch Nazis if they agreed to go and fight. The United States negotiated for the independence of the Philippines, but intervened militarily in Korea and Vietnam, and were heading towards an attempt to invade Cuba – prevented by Cuban and Soviet military moves. Repeats of the Nazi war of conquest, of wars among the small number of countries that dominated the world’s economy, the imperialist countries, was made illegitimate. As for the colonies’, even ongoing occupation was defended as legitimate until the anti-colonial resistance forced concessions or defeated the conquest. There was also the Soviet Union, a joint founder of the United Nations with veto power on the Security Council. Having seen how the Soviets fought the Nazis, conquering the Soviet Union appeared an impossible project for the imperialist powers. So, the threat of destruction, rather than conquest, was made with the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan. All this led to the madness of MAD – Mutually Assured Destruction. But as for a war of conquest against the formerly colonised world? that remained legitimate. And this was always a fundamental rule of the whole colonial period: one rule for the colonisers and another for the colonised. Contemporary Consequences Even while independence was won by many countries, their original conquest with its massacres, massive plunder and blockage of development and progress has never been recognised as illegitimate. A country like Indonesia was plundered of tens of billions of dollars, as calculated by scholars of colonial finances, while there was no education system, nor any modern manufacturing, built by the Dutch. Debt and savage socio-economic backwardness were the legacies of Dutch colonialism. It was little different in any other colony. Two thirds of humanity were colonised when European superiority in naval and military technology was used for conquest and plunder, and not for spreading Liberty, Fraternity and Equality. The scientific revolution and the Enlightenment were not able, and did not at all, challenge the morality of conquest. Indeed, even in 1945, it was the destructiveness of modern warfare that de-legitimised policies of conquest, not any philosophical rejection. The refusal to address the consequences of colonialism for that huge section of formerly colonised humanity has not simply meant avoiding any discussion of reparations. In fact, the socio-economic backwardness of Global South countries has been exploited as a weakness to allow them to be further plundered and subject to imperialist economic stranglehold. Whenever necessary, they are subject to invasion, low-intensity military intervention, shock-and-awe terror bombing, coups and whatever else might be deemed necessary. After WW2 it has been the states who dominate NATO, particularly the United States as well as some junior allies such as Australia which have shown that as far as the Global South countries go, conquest is still legitimate, even if not always in military form. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reduced economic strength of the Russian Federation – even while nuclear armed – this attitude frames American policy towards Russia, as well as China. Russia and China are, at the moment, the largest of the defiant states – in defence of their own development, even if on a capitalist economic path, or some hybrid of that. The idea that conquest is still legitimate is primarily propelled by imperialism’s need, especially the United States’ need, to deepen its exploitation of the Global South and their ruling class’s perpetual colonial mentality. However, if this openness to conquest is allowed to grow all, hell can break loose, literally. To struggle against war and for peace today means strengthening solidarity with countries of the Global South in all of their efforts to defend themselves from attempts at imperialist conquest, whether direct military attacks, by encirclement, by proxy wars, economic blockades or commercial wars. The vast majority of Global South countries are ruled by capitalist classes whose thinking about how they should defend themselves may often be characterised by the narrowness of their class outlook, ignoring the role of popular forces in their own or other countries. They may not make the best decisions, although indeed they may also make the only decisions available to them, which may still be horrible. What should determine a sane, humane outlook is whether or not imperialism’s stranglehold on the Global South will be strengthened or weakened. The weaker the stranglehold, the greater potential for new movements to emerge and grow. And, of course, there are some Global South countries that are governed by genuine socialist governments and peoples, such as Cuba. For such countries a special solidarity is due. And never forget, the US regularly breaks its promises. So yes, President John Kennedy did promise not to invade Cuba, but while conquest is still considered legitimate among the imperialists, solidarity is a necessary part of a legitimate wariness. Archives September 2023 President Petro hopes the Asian nation can help Colombia with transportation projects based on the use of trains and electric technologies. On Thursday, Colombian President Gustavo Petro announced that he will travel to Beijing, where he will meet with President Xi Jinping to discuss the future of Bogota's subway. Its construction is currently being handled by a Chinese consortium. "I have an interview with the Chinese president on October 25," he said, adding that he hopes the Asian nation can help Colombia with transportation projects based on the use of trains and electric technologies. With this trip, Petro will continue a pragmatic policy of friendship with China that began on Feb. 7, 1980, with the establishment of diplomatic relations during the administration of the then-Colombian President Julio Cesar Turbay. Since then, the relationship has been growing, and China became Colombia's second-largest trading partner in 2010. In 2022, bilateral trade amounted to US$18 billion, with US$2 billion corresponding to Colombian exports and US$16 billion to imports of Chinese goods and services. China's Ambassador to Colombia Zhu Jingyang assured that "China is interested in receiving more Colombian products and developing a process for more products to access the Chinese market, as recently happened with Colombian beef." President Petro's emphasis on the relationship with China is also evident in his appointment of the film director Sergio Cabrera as ambassador in Beijing. Cabrera spent his adolescence in that Asian country, where he learned to speak Mandarin and even became a Red Guard. Currently, Bogota's subway is Colombia's largest engineering project. For the construction of the first line, the China Harbour Engineering Company Limited and Xi'an Metro Company were selected in 2019. Archives September 2023 9/30/2023 Venezuela: Gov’t to Launch China-Backed Anti-Poverty Program. By: Andreína Chávez AlavaRead NowThe Social Equality and Happiness Mission will adapt the Chinese experience to the Caribbean country’s reality to alleviate poverty and inequality. Caracas, September 21, 2023 (venezuelanalysis.com) – The Venezuelan government has announced a new social program focused on fighting poverty and inequality, which will be supported by China’s International Poverty Reduction Center. On Monday, during his weekly TV program, President Nicolás Maduro said that the “Social Equality and Happiness Mission” was “almost ready” to be launched and its main purpose is to “optimize the fight against inequality, against poverty and to build a more harmonious country.” Although Maduro did not give details, he stressed that the social program will work alongside the Chinese anti-poverty center. The government led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been responsible for lifting over 850 million people out of poverty in the Asian giant since 1980. “In 1981, almost 90 percent of the Chinese population was below the absolute poverty line as measured by the World Bank,” —the Venezuelan leader went on to explain in his national broadcast —“but in 2019 the figure did not reach 1 percent and by the end of 2020 the Chinese government announced poverty eradication in the country.” China’s success story in reducing poverty has been recognized worldwide as it has gone hand in hand with sustained economic growth and rapid industrialization. Beijing has also created alliances with countries from the Global South to help advance socioeconomic cooperation. Venezuela’s new social program follows President Maduro’s recent trip to China, where he met with President Xi Jinping to establish an “all-weather strategic partnership” and signed 31 cooperation agreements. The main ones include China’s support for Venezuela’s special economic zones (SEZs), poverty reduction efforts and boosting the country’s national electric grid and public healthcare system. Maduro clarified that the Chinese experience will be adapted to the Caribbean country’s reality, its culture and people’s most important necessities. Currently, Venezuela does not have official data regarding poverty and inequality rates. In 2014, the government stopped publishing numbers as the country entered an economic crisis after oil prices plunged globally and hyperinflation crushed working-class people’s purchasing power. The situation was aggravated by the imposition of unilateral coercive measures by Washington and its allies as part of a regime change strategy. The sanctions levied against the Caribbean nation have targeted every key sector of the economy, especially the oil industry, the country’s main source of foreign revenue. In 2017, the US Treasury imposed sanctions against state oil company PDVSA followed by an oil embargo in 2019. Washington likewise banned diluent and fuel imports exacerbating fuel shortages affecting electricity generation and agricultural production. In response to the US-led blockade, the Venezuelan government implemented a hybrid economic liberalization program and a nationwide de facto dollarization while advancing efforts to diversify the economy and increase non-oil revenues. As a result, the economy began to grow again in 2021 after seven years of contraction. Inflation receded to the lowest levels in nearly a decade and small-scale private enterprises expanded. However, some analysts have pointed out that the economic reforms have contributed to a significant increase in inequalities due to growing private sector benefits, the de-regularization of labor and stagnated public sector workers’ wages. Venezuela’s minimum salary currently stands at 130 bolívares (around US $5). President Maduro has not directly addressed complaints about low wages and the loss of social benefits from public sector workers, particularly in the education sector, who have staged several protests alongside workers from the industrial sector. The administration is likewise engaged in dialogue with trade unions regarding salary adjustments with mediation from the International Labor Organization (ILO). Recently, the Venezuelan government has been primarily focused on resolving quality-of-life issues by remodeling deteriorated schools and hospitals and attending to public service problems through the so-called “1×10 System.” The initiative allows people to denounce issues within their communities using a digital app, breaking away from the bureaucratic processes to receive a rapid response. According to the latest report, almost 1.5 million cases have been attended through the app-based program since its launch. The issues mostly relate to water, electricity, roads, internet connection and cooking gas supply. During the Hugo Chávez government (1999-2012), Venezuela’s household income poverty reduced from 42 percent in 1999 to 27.3 percent in 2013. Meanwhile, structural poverty fell from 29.3 percent in 1999 to 19.6 percent in 2013. The achievement responded to a series of social programs, some of them in cooperation with Cuba. Archives September 2023 In the United Kingdom, the BBC prepared and published data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in January about different nations’ growth forecasts for 2023 and 2024. The BBC foregrounded some really bad news for the UK. Of nine major industrial economies--the G7 (the U.S., Canada, Japan, Germany, the UK, France, and Canada), plus Russia, and China--the UK would be the only one to suffer real economic decline: a contraction in its 2023 GDP (its total annual, national output of goods and services). So dubious a distinction for the UK followed the long political night of rule by the Conservative Party. That night’s darker moments included austerity after the severe 2008-2009 global capitalist crash, scapegoating Europe for the UK’s economic troubles, Brexit taking place during the peak of that scapegoating, enjoyment of COVID cocktail parties by former Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government that it prohibited for the British public, and endless, transparent, and cringeworthy lying to the public when caught and exposed. But the BBC’s report on the new IMF data was shocking about far more than the poor performance of the UK economy. For the rest of 2023, the IMF says China’s GDP will grow more than 5 percent or more than twice Japan’s GDP growth rate. All other G7 countries will grow their GDPs more slowly than Japan. China’s growth rate will be more than triple that of the U.S. in 2023. Finally, the IMF’s projected GDP growth for 2024 shows both Russia and China growing much faster than any G7 country. These comparative forecasts comprise a reality check that clashes with most politicians’ statements, mass media accounts, and propaganda barrages (worsened by the Ukraine war) emerging from the G7’s old capitalist establishment. The BBC report was thus both rare and arresting. For 30 years, skepticism and disparagements confronted China’s claims about its economic growth. When these attempts to debunk Beijing’s claims were subsequently proven wrong by the country’s stunning record of superior economic growth, the intensity of these efforts nonetheless mounted. Disbelief in China’s economic achievements grew even as in-person visits to China confirmed high rates of industrialization, internal migration and urbanization, and fast-rising mass consumption levels. The need to disregard China’s economic transition from extreme poverty to economic superpower status rivaling the U.S. reminds us of the Cold War-driven nonrecognition of Soviet economic achievements after 1945. A parallel nonrecognition figures again in the G7 sanctions strategy against Russia over the Ukraine war. For anyone seriously interested in understanding the momentous changes now sweeping across the world economy, one question looms. How do we account for the gap between what the old capitalist establishment says (and may even believe) and what is real? The answer is that we are confronted with a combination of denials and pretenses that are caused by the conjoined decline of U.S. capitalism and its global empire (or hegemony). Those declines have occasionally become clear enough, at least fleetingly, to observers within the old capitalist establishment. For example, such key moments include the U.S. military’s inability to “win” local wars even against poor countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq. Another example was the U.S. medical-industrial complex’s subpar performance in managing the high number of COVID deaths and illnesses. U.S. capitalism’s crash in 2020 and into 2021 was severe and then was followed immediately by a bad inflation and then a fast, destabilizing tightening of credit: not exactly a stellar economic record. Debt levels of the U.S. government, corporations, and households are at or near record levels. Inequalities of wealth and income, already extreme, keep rising. A public viewing such facts might reasonably wonder whether something bigger is at play beyond these events being seen in isolation. Might there possibly be a systemic problem? But before such a line of thought can jell into a conscious question, let alone any serious pursuit of an answer, denial sets in. A systemic breakdown seems an unbearable thought, so denial of systematicity is undertaken. Statements about specifics are carefully crafted to omit connecting them to their context of a declining capitalist system. Evasion of the systemic dimension leads to undervaluing the dangers each particular problem or crisis presents. Like rose-colored glasses, anti-systemic glasses make economic problems appear less dangerous, narrower, and more limited in effects than they actually are. The anti-systemic bias is a form of denial. Consider, for example, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen or other officials when they bemoan deepening U.S. economic inequality. They do not refute nor even seem able to imagine that within a declining capitalism, the richest and most powerful will use their positions to shift the costs of its decline onto others. For example, raising interest rates these days to counter inflation—instead of imposing wage-price freezes like former President Richard M. Nixon did in 1971 or imposing a goods rationing system as former President Franklin D. Roosevelt did in the 1940s—is an anti-inflation policy choice. The burden of this option falls more heavily on middle- and lower-income recipients than on the rich. Similar cost-shifting is entailed by a policy of huge federal budget deficits because they are financed by borrowing disproportionally from (and thus paying more interest to) the richest parts of society. Yet mainstream G7 discussions of those policy choices and deficits rarely link them to the decline of U.S. capitalism and its global hegemony. Complementing denial of systemic problems in G7 economies are loud pretenses about their good health in contrast to problems elsewhere. Like the repeated affirmations about a “great” U.S. economy contrasted with deep difficulties afflicting the Russian and Chinese economies. Ironically, those difficulties are regularly rendered as systemic, flowing from the “natures” of an “authoritarian” or socialist economic system. For example, in recent years, mainstream U.S. media reported that Russia’s ruble would soon “collapse,” that China’s building boom was collapsing, that China’s anti-COVID policies were wrecking its economy, and so on. Apropos Russia’s economy, the late U.S. Senator John McCain dismissed Russia as a “gas station masquerading as a country.” Around former President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden, the argument was often advanced that beyond all policy specifics (regarding tariffs, trade, sanctions, Hong Kong, and Taiwan), economic system change in China was necessarily a goal on the horizon. Reality undermines these denials and pretenses. That is one reason why they struggle so hard to obscure reality. For example, China’s economic performance, as measured by its world-leading GDP growth over the last quarter century, undergirds its confidence in and loyalty to its particular economic system. The BBC’s graphic only further confirms that confidence. By the same logic, that graphic challenges the systemic self-confidence of the old G7 capitalist establishment. Denials and pretenses are not likely to be sustainable responses to the widening differences between G7 performance and the emerging (and already larger in GDP terms) alternative gathered around the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Of course, both G7 and BRICS are heterogeneous assemblages including many significant differences among their members. Nor is there any guarantee that either bloc will retain its capitalist or socialist components or make transitions between them. Relations between the G7 and BRICS, like any possible transitions among various forms of capitalism and socialism, are now crucial social issues and struggles. Social movements inside both blocs will shape those issues and those struggles. To do that, especially if wars are to be avoided, social movements will need to set aside denials and pretenses and face realities. AuthorRichard D. Wolff is professor of economics emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a visiting professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University, in New York. Wolff’s weekly show, “Economic Update,” is syndicated by more than 100 radio stations and goes to 55 million TV receivers via Free Speech TV. His three recent books with Democracy at Work are The Sickness Is the System: When Capitalism Fails to Save Us From Pandemics or Itself, Understanding Socialism, and Understanding Marxism, the latter of which is now available in a newly released 2021 hardcover edition with a new introduction by the author. This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute. Archives September 2023 Hundreds of thousands of guns made in the United States propel a gang war that has turned Haiti’s capital Port-au-Prince into a war zone. Domini Resain, the mobilization minister of MOLEGHAF, holds a sign that reads “MOLEGHAF Says no to Foreign Meddling and Occupation” at a protest in 2022. MOLEGHAF is the National Movement for Liberty and Equality of Haitians for Fraternity. (MOLEGHAF) Guns, gangs, hopelessness, and hunger have reached new heights across Haiti. Port-au-Prince is currently embroiled in a multidimensional war that is affecting every facet of life in the island nation’s capital. CNN reports that Haiti’s crime rate has more than doubled in the past year, with over 1,600 rapes, kidnappings and murders reported in the first three months of 2023. Real numbers are likely double official statistics because in the most oppressed bidonvils (slums, translated from Haitian Kreyòl) such as Belè, Solino, Site Militè, or Site Solèy, there is scant reporting on the dire reality faced by residents. Inflation in Haiti has surpassed 50 percent. There is no gasoline in the pumps and the black-market cost is $15 per gallon. Food is scarce. According to the World Food Program, a total of 4.9 million Haitians—nearly half the population—do not have enough to eat, and 1.8 million are facing emergency levels of food insecurity. This grueling reality has spurred a hybrid war that has only intensified as gangs fight one another and the Haitian National Police and terrorize local communities. The crisis is deepened by the lack of elected leadership in the country after unpopular president Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in July 2021. At the center of this neocolonial maelstrom are nearly one million U.S.-made guns that have illegally made their way ionto the western side of the island the Spanish crown once called “Hispaniola” or “Little Spain.” The U.S. Gun Crisis is Haiti’s Gun Crisis Prohibition-era rum runners on the East Coast of the United States had a formidable opponent: the United States Coast Guard. Coast Guard efforts to stop trafficking led to the development of faster boats, advanced tactics, and countless barrels of destroyed booze that would have otherwise helped line the pockets of organized crime.

Gun violence in Haiti has spiraled out of control as the nation reels from U.S./Core Group neocolonial domination, natural disasters, foreign-sponsored presidential coups, and the threat of another U.S.-led invasion and occupation. “Straw buyers” legally purchase guns in the states with lax regulation and sell them to gun smugglers, often in the Haitian-American community, who then sell them to buyers in Haiti for a massive profit. The United States of Guns The United States of America is the most violent country in the world. The firearm homicide rate in the United States is 13 times higher than that of France and 22 times higher than the European Union. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) reported 26,328 suicides and 20,598 homicides in 2021, the vast majority committed with firearms. There are 120.5 guns per 100 Americans, far more than any other country globally. There are a total of 393,347,000 civilian firearms in the United States, meaning there are roughly 60 million more firearms than people. About 4 percent of the world's population has 40 percent of the world's civilian-owned guns. The Pentagon operates 750 foreign military bases abroad in over 80 “sovereign countries.” The United States has more than three times as many overseas bases as all other nations combined, costing taxpayers an estimated $55 billion every year. There are more wars now than any other time since WWII, with the U.S. military involved either covertly or overtly in many of them. Smith and Wesson won the gold medal for the generation of violence, producing 2.3 million guns in 2021, followed closely by the firearms manufacturers Ruger and Sig Sauer. The profits of firearms manufacturers have reached historic levels, and gun companies export roughly half a million guns per year. The mass media promotes suburban panic by distorting the reality of violent crime, which has actually been on the decline nationwide after peaking in the 1980s. Imperialist projects like the bombing, invasion, and occupation of Iraq, Afghanistan, Yugoslavia, Libya, and others have shown that the United States, in the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, continues to be the world’s “leading purveyor of violence” at the expense of diplomacy. Slashing diplomatic budgets while consistently funneling more resources to the Pentagon has locked the country onto an exceptionally bloody warpath. Politicians corrupted by powerful gun lobbies like the National Rifle Association (NRA) keep regulations relaxed. A CDC report decried the fact that gun violence is the leading cause of death among U.S. children between the ages of one and 18, yet meaningful legislation seems like a sick joke in the wake of events like the shootings in Sandy Hook, Uvalde, and hundreds of others. The United States gun crisis has been exported to Haiti, where U.S. guns are killing at harrowing rates. Thousands of youth have given up on life and turned to the only way they see how to survive: gang life. Co-author Danny Shaw accompanies Domine Resain in a community meeting with leaders in Okap. (Danny Shaw) Caribbean Blood, U.S. Sharks The Haitian people and their grassroots leadership have been telling us for decades that their current and past crisis goes well beyond Haiti. Philosophy Professor Kervins Victor from the State University of Haiti elucidates the hierarchy behind the violence in Port-au-Prince’s ghettos “charting the relationship between gangsters with ties on the top of the social pyramid and gangsters in flip flops at the bottom.” Based on information supplied by local informants in Kap Ayisyen, the capital of the 1804 revolution in the north of the country, on any given day crates and containers with guns arrive in Haiti’s Atlantic Ocean ports.

Politicians like DeSantis and Trump make a name for themselves scapegoating immigrant and oppressed communities but skirt over the push factors that motivate millions to risk their lives fleeing the Global South. Behind the scenes, the NRA has waged a campaign to elect judges in state races and influence supreme court judges, with anti-democratic repercussions far beyond Washington. A Smugglers Paradise The players on the frontlines of this international operation include Jean Gilles Jean Mary, accountant for the Episcopalian Church of Haiti based out of Site Solèy, one of the largest and most oppressed slums in the Western Hemisphere. From 2017 to 2021, shipments officially marked as aid intended for the church contained pistols, rifles, and ammunition. The Episcopal church has denied any involvement but Jean Mary was accused in August 2022 of providing Episcopal Church funds to arms traffickers for over four years before being caught by Haitian investigators. He was taken into custody just 48 hours after the police arrested Father Frantz Cole for "arms and ammunition trafficking, smuggling, tax evasion, tax fraud, crimes of enrichment, and laundering of assets resulting from serious crimes.” Dominican Today reports that in the bust the Haitian National Police seized a container in the port of Port-au-Prince that contained 18 “weapons of war” and nearly 20,000 cartridges. No one knows how many weapons get through Haiti’s porous borders daily, but Reuters reports that the seizure is merely “the tip of the iceberg.” A naturalized U.S. Marine was caught in late 2020 attempting to sneak weapons and body armor into the country in an attempt to train the Haitian armed forces and run for president of Haiti. When arrested by Haitian customs officials at the airport, he claimed that the arms trafficking was part of a plan “to engage in foreign armed conflict,” a chilling thought considering he was an active duty U.S. Marine. The most recent case from May involved a Cuban-American arms dealer from Miami, Elieser Sori Rodríguez, who was caught by Dominican authorities attempting to smuggle 33 firearms, including rifles, pistols, and shotguns, along with 350 boxes of ammunition, 56 magazines, and hundreds of cartridges. The Dominican government discovered that Rodríguez aimed to transport the arsenal into Haiti at the border city of Jimaní. Trafficking guns is big money. The Vienna-based U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime reports that “popular handguns, selling for $400-$500 at federally licensed firearms outlets or private gun shows in the U.S., can be resold for as much as $10,000 in Haiti.” More powerful weapons are typically in higher demand by gangs and are sold at correspondingly higher prices. The majority of smuggling cases covered by the media involve small fry fall guys. The police attempt to make an example out of petty hustlers, while well-protected and connected actors operate with impunity. Given that there has been no updated count since the notorious half million figure reported in 2021, estimates indicate the number of illegal guns in Haiti has doubled for a population of 11.5 million people. This is an operation involving serious funding and coordination, expertly handled by insiders on both ends of the transaction. Tchadensky Jean Baptist (center), a student, artist, and anti-imperialist organizer who was killed by a sniper in Port-au-Prince on March 21, 2023. He is pictured here with his partner Tedina and a community volunteer. (Image courtesy of the family) A Failed State or Successful Imperialism? This year the World Bank ranked Haiti as the 179th most corrupt country out of 190 countries evaluated. The average customs official in Haiti earns under $10 per day, making it one of the easiest places to bribe such bureaucrats in the world.

From June 11 to 13, Caribbean Community (CARICOM) heads of state met in Jamaica to discuss, among other matters, a potential fourth U.S. invasion of Haiti in 100 years. In representation of Haiti’s diverse grassroots justice movement, union leader and philosophy professor Josué Mérilien drafted 12 concluding points from the summit, circulated on WhatsApp among grassroots movements in Haiti and the diaspora. The top two demands are telling: 1) “Put an end to the interference of the imperialist powers and recover Haiti’s national sovereignty,” and 2) “put an end to indecent international support, particularly from the USA, Canada and France, to the criminal PHTK government of Ariel Henry and the establishment of a credible transitional government.” The United States’ gun crisis is Haiti’s gun crisis. The past century of intervention has shown that this is not the first time U.S. action and inaction has been responsible for the proliferation of violence in Haiti. The Haitian people are saying "no” to a military occupation and “yes” to the recovery of the nation’s wealth and reparations after centuries of foreign exploitation. AuthorJan Critchfield is a U.S. Army veteran of the war on Iraq. He was deployed to Baghdad in 2004, where he wrote and took pictures for First Cavalry Division public affairs. He currently photographs and tinkers with bicycles in New York. This article was produced by Nacla. Archives September 2023 9/26/2023 World War II revisionism on full display in Nazi’s visit to Parliament By: Owen SchalkRead Now

World War II revisionism in Canada is leading to some shocking, dangerous new places.

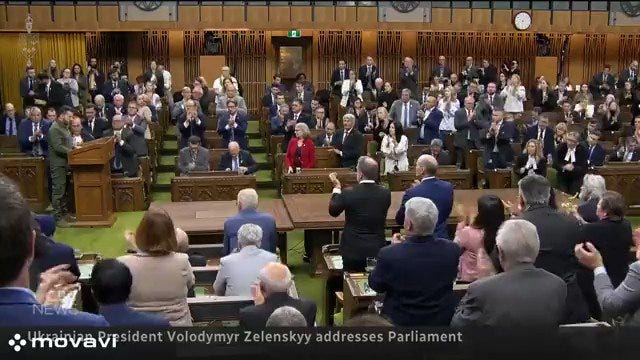

Parliamentarians across party lines, including Trudeau, treated Hunka as a guest of honour. House Speaker Anthony Rota introduced Hunka as a “hero” and a “veteran from the Second World War” who had “fought… against the Russians.” Rota then said that the House of Commons “thank[s] him for all his service” in the fight against Russians during the Second World War. Neither Rota nor anybody present thought to mention the obvious: that those fighting Russia during the war were almost exclusively Nazis.

Not only did nobody seem to notice this shocking omission, the entire House of Commons and President Zelensky rose to applaud Hunka, who served in the 14th SS Division Galicia. Shortly before the end of the war, the unit was renamed the “First Ukrainian Division” in order to remove its association with the Waffen-SS, the military wing of the Nazi Party. In fact, the SS Galicia “subscribed to and served the ideology of Adolf Hitler and SS leader Heinrich Himmler.”

Hunka is unrepentant about the years he spent fighting for Hitler’s Germany. He proudly posted photographs of himself in uniform on a blog for Ukrainian veterans of the division. In another post, Hunka describes the period under Nazi occupation from 1941 to 1943 as “the happiest years of my life.”

Now that the media is reporting on the Canadian government’s celebration of a Nazi, politicians are rushing to assign blame. Rota has taken responsibility for inviting Hunka, but his statement that the decision to invite Hunka was “entirely [his] own” strains belief. Surely the Prime Minister’s Office would fully vet every formal guest invited to a speech by a foreign head of state in the House of Commons (particularly one who is acknowledged directly). Predictably, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre is blaming Trudeau for allowing the Nazi veteran to attend the session. But it is hard to deflect the blame onto one person given the entire Parliament, not just Rota or Trudeau, gave a standing ovation when Hunka was introduced. The reality is that historical revisionism in Canada runs much deeper than one political “gaffe.” There are today numerous statues honouring the SS Galicia division in Canada, including a bronze bust of Ukrainian Holocaust perpetrator Roman Shukhevych in Edmonton. When someone vandalized the Shukhevych statue with the words “ACTUAL NAZI” last year, the Canadian media refused to condemn Shukhevych as a Nazi war criminal. Coverage mainly focused on the act of vandalism itself, while major news outlets like CTV and CBC equivocated on condemning Shukhevych; articles noted that he played a “controversial” role in history and that he is “celebrated by some as a Ukrainian military leader.”

Many groups, including national Jewish organizations, have tried to draw attention to the creeping rehabilitation of Nazi war criminals across Canada. Yet media and politicians continue to excuse the crimes of Ukrainian Nazi collaborators, particularly in the wake of Russia’s invasion.

Canada’s openness toward Ukrainian Nazi collaborators goes back much farther than is widely known in this country. By 1950, Western countries had welcomed thousands of members of the OUN and the SS Galicia division. For its part, Canada welcomed between 1,200 and 2,000 veterans of the Galicia division—including, it seems, Yaroslav Hunka. Even Timothy Snyder, a vocal supporter of Ukrainian nationalism and a proponent of the anti-communist “double genocide” theory, has described the OUN’s actions in Poland as “not military operations but ethnic cleansing.” Snyder writes: Ukrainian partisans and their allies burned homes, shot or forced back inside those who tried to flee, and used sickles and pitchforks to kill those they captured outside. Churches full of worshipers were burned to the ground. Partisans displayed beheaded, crucified, dismembered, or disemboweled bodies, to encourage remaining Poles to flee.

The Canadian Jewish Congress condemned the government’s embrace of Ukrainian Nazi collaborators after the war. Nevertheless, Canada was noted for its “lax pursuit of accused war criminals,” with a New York Times headline labelling Canada a “Haven for Nazi Criminals.” With this history in mind, it is hardly a shock there are so many statues glorifying Nazis on Canadian soil.

The victims of Nazism cannot, and must not, be lumped together with the so-called victims of communism: the ‘victims’ of Soviet forces in the Second World War were the Nazis, their collaborators and the various fascist puppet states who allied with Hitler.

At its heart, Canada’s adoption of Black Ribbon Day represents “deliberate rewriting of history to suit contemporary geopolitical interests.” It is, Noakes argues, “designed deliberately to relativize the Holocaust and even the entirety of the Second World War” to make the communist forces seem just as bad or even worse than the Nazis.

Parliament’s decision to honour a Nazi can be viewed as the latest stage in a national attempt to rewrite the history of the Second World War to serve contemporary political objectives. It is telling that Hunka was introduced as someone who “fought against the Russians.” Which Russians he was fighting, which army he was serving, and why seem to be irrelevant to the House. The simple fact that he fought Russia at some time, for any reason, is enough to merit a laudatory welcome. Many of those who honoured Hunka are self-described liberals who claim to value democracy, human rights, and the protection of the marginalized above all. But the Canadian government’s tendency to twist history to suit contemporary political aims—namely, the demonization of all things Russian—has led them toward a startling kinship with an unrepentant Nazi. Strange bedfellows? Hardly. Canadian leaders have long excused the crimes of Ukrainian Nazi collaborators, and long courted the support of far-right European diaspora communities. Friday’s appalling display in the House is the predictable culmination of decades of deliberate government policy. AuthorOwen Schalk is a writer from Winnipeg, Manitoba, and a columnist at Canadian Dimension magazine.

This article was produced by Monthly Review.