|

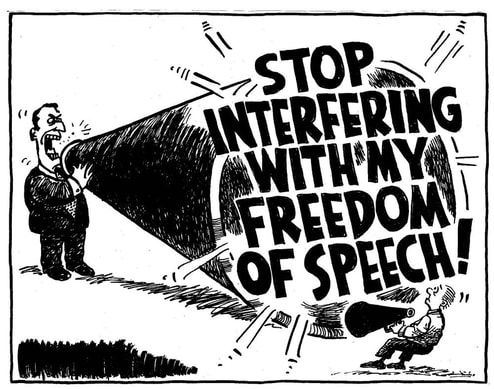

When considering the philosophy of Karl Marx, one must consider first and foremost the role of alienation. The fundamental problem with capitalism is that it alienates the worker from the product of their labor. Marx developed this idea after developing his thoughts on the forms of alienation produced by religion. While the details of this transformation are beyond the scope of this paper, I highly recommend Why Read Marx Today? This work, written by contemporary philosopher and former professor of philosophy at University College London, Jonathan Wolff, concisely sketches the development of Marx’s thoughts on alienation as a product of religion to alienation as a product of capitalism. We may regard alienation as an evil precisely because it denies the human being the fruits of the most fundamental part of our nature; viz., alienation robs us of the full value of our creative faculties. The human being is inherently creative. Even so-called “uncreative” people are in fact extremely creative. Every day we create something—whether it be food, a planned experience with a loved one, or an especially clever email to a boss. Creativity should not be understood as a characteristic only attributable to the likes of Chopin and Tchaikovsky, or Van Gogh and Picasso. The creative force is the driving force of humanity, and this is precisely why the alienation from the fruits of our labor by capitalism is so insidious. Furthermore, any labor that creates value is a creative behavior. Acknowledging the theory of surplus value developed by Marx, we can recognize that the expropriation of the product of the mass’s labors is the expropriation of the driving force of their existence. One of the great beauties of humanity is our ability to create meaning itself. Could it be that the more general drive to create new means of interacting with the world is also what forces the conscious development of meaning in our lives? After all, it is the development of technology which allowed for historical human civilizations to evolve in the first place. Directly through the development of new means of production does history march. As humanity moves through new phases of development, we are forced to develop new types of meaning in order to justify to ourselves the burden of rising self-consciousness. The burden of self-consciousness is perhaps the most ancient burden in the history of human thought. One might easily interpret the Biblical story of Adam and Eve as a reflection of this manifestation of the collective subconscious. The curse of the knowledge of good and evil is the “original sin” in the broader Christian tradition, and one may quickly find the germ of truth present in material reality that is captured in this myth. By coming to self-awareness humanity has burdened itself with the knowledge of choice. It is directly our awareness of our own actions, our own ability to apply causes to the material world for a specific effect that drives our need to create meaning in our own lives. The beauty of non-human animal consciousness is that they simply cannot call into question neither their means or their ends. While it is clear non-human animals, especially other mammals, have some function akin to deliberation, it is unlikely that they are able to call into question the legitimacy of their ends. But how did we get to question the legitimacy of our ends? There is no definitive answer to this, and if there is a scientific answer to be found it will be found by anthropologists, not philosophers. However, I suspect that the development of agriculture sparked the first real questioning of the validity of our ends. While we have evidence of pre-agricultural art and artifacts, these can be seen to be largely descriptive images of the world around them. It is not until after the agricultural revolution some 12,000 (or more) years ago that clearly interpretative art began to arise. But why agriculture? The simple answer is that the development of agriculture took humanity off the well-trodden path that our evolution had theretofore plotted for us (to speak very loosely). While I can only speculate, it seems to make good intuitive sense that in shirking off the instincts given to us by direct natural selection, through the development of new technologies, our ancestors were forced to question these new ends simply in virtue of their being so new. Agriculture allowed for the emergence of the most complex social structures on earth, and, for all the evidence we have, in the entire universe. Neurological systems simply could not evolve quickly enough to keep pace with the amazing phenomenon that is cultural evolution. Forced to confront systems so foreign to the patterns of nature under which our neurological systems were developed, human beings may well have been forced to create new meaning to match the novelty of these ways of life. Perhaps meaning-making is just the natural response such highly complex brains are forced to take when confronted with such starkly different ends available to them than presented through the subconscious instinct shaped by natural selection over countless ages. It may just be the case that those humans who could not make new meaning out of their lives simply died out—or perhaps not, if we are to look at the increasing rates of suicide and depression in many industrial societies of today. “All of this is very interesting (and quite dry) but what does it have to do with free speech?” I imagine the reader is asking themselves at this point. Let us recognize that speech itself is inherently creative. In every speech act, the human being designs a meaningful construct to communicate something, however benign, to another person. In fact, we hold many of those talented in language to the highest esteem— Mary Shelley, writing Frankenstein at nineteen years of age, the greatest novel of all time, is a favorite example. As it turns out, speech is one of our most cherished creative aspects. Think back to Descartes, who ultimately appeals to an internal speech act to justify his own existence—cogito ergo sum, I think therefore I am. However, this type of thinking is just an internal speech act! While here we do not wish to defend Cartesian dualism, or really anything promoted by Descartes, the famousness of this quote of his is illuminating to just how dear our speech is to our identities as human beings. Most people greatly value the quality of their own thoughts, and the ability to express those thoughts at-least-sufficiently well through language. To take it even further, speech is largely the vehicle by which we make meaning out of our post-agricultural revolution existences. Is it not through language that we call into question good and evil? Is it not through language that we pierce through the veil of appearances with the natural sciences? Is it not through language that we express our love? Certainly not in all cases, but that is beside the point. The fact of the matter is that we do use language for these things, and even the other things we use for these purposes are fundamentally products of our creative nature, such as painting or music. We can now see the evil that is the alienation of the human being from their own speech. Certain strains of thought in the Marxist tradition are very unfriendly to the concept of free speech, but they do not realize that in doing so they are lowering themselves to the criminality of the capitalist class themselves. The aim of the liberation of the working people of the world is the end of alienation. Any Marxist theoretician who strays from the ideal of free speech forgets the vitality of the dissolution of social structures which inherently alienate individual human beings. Let us now sketch a more condensed version of our argument: 1. Alienating a human being from their creative nature is evil. 2. Alienating a human being from the products of their labor is tantamount to alienating a human being from their creative nature. 3. Speech is a product of human labor and, thereby, the human creative nature. 4. Therefore, alienating a human being from their speech is evil. 5. Censorship of speech alienates human beings from their speech. 6. Therefore, censorship is evil. The only exception to the value of free speech is speech that is directly calling for violence. As the right to life is more fundamental than even the right to the fruits of one’s labor, as life itself is that which allows for the creative force to exist, the right to freedom of speech must be subordinated to the right of people to remain safe. Speech encouraging direct violence towards persons or groups cannot and should not be tolerated, as the concern for the existential security of every person must come before any other concerns. Thus, it is acceptable to censor Nazi propaganda, for instance. However, censorship should be used with great hesitation, as censorship is one of the greatest threats to democracy as a whole. The unabashed endorsement of censorship by some in the Marxist tradition undermines the anti-hierarchical, democratic nature of the Marxist goal, and should be regarded as antithetical to the movement. About the Author:

Jared Yackley is an undergraduate student of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. His primary focuses are in epistemology, history, and political philosophy. Yackley hopes to apply the principles of dialectical materialism to contemporary issues, both philosophical and political.

0 Comments

|

Details

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed