|

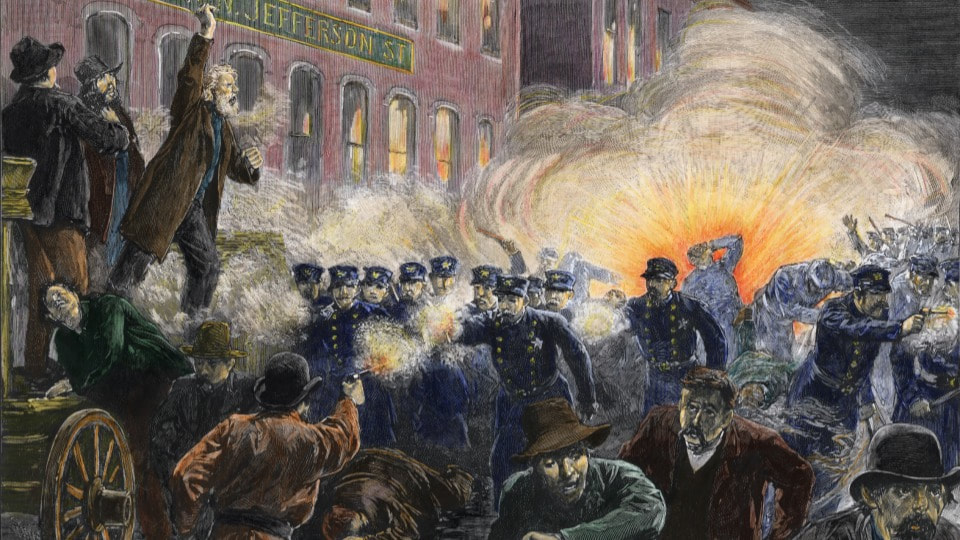

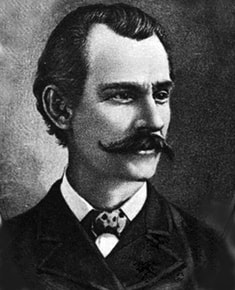

This 1886 engraving was the most widely reproduced image of the Haymarket massacre. It shows Methodist pastor Samuel Fielden speaking, the bomb exploding, and the riot beginning simultaneously; in reality, Fielden had finished speaking before the explosion. | Chicago Historical Society CHICAGO—On the morning of Oct. 6, 1886, Albert Parsons, native of Alabama, whose brother was a general in the Civil War, rose in a Chicago courtroom to make the last speech of his life. He was facing his doom as one of the convicted co-called “anarchists,” one of the “detested aliens” who had been seized in the police frame-up following an explosion on Chicago’s Haymarket Square during a workers’ demonstration on May 4. Parsons spoke long and well. He was going back over his life, telling the remarkable story of how the boy who ran with the Texas trappers and Native American traders as a kid grew up to become a leader of industrial strikes and an agitator for a new social system. “The charge is made that we are ‘foreigners,’ as though it were a crime to be born in some other country,” he said. “My ancestors had a hand in drawing up the Declaration of Independence. My great great grand-uncle lost a hand at the Battle of Bunker Hill.” His speech then took an edge of defiant bitterness. “But I have been here long enough, I think, to have the rights guaranteed by the Constitution of my country.” Ringing up to the ceiling of the room which was to be his death chamber, the voice of this man, a printer in the shop of the Chicago Tribune and a labor organizer after the early days of the frontier, became deep with exaltation: “I am also an internationalist. My patriotism covers more than the boundary lines of a single state; the world is my country, and all mankind my countrymen.” Parsons was speaking against a force, a conspiracy that was determined to throttle him, and he knew it. But why was the state determined to see him dead? The 8-hour dayThe demand for an 8-hour workday was sweeping over America at that time as workers demanded relief from the 12-, 14-, or even 16-hour days that were the norm. On May 1, 1886, hundreds of thousands of workers launched a general strike—the first in the history of the United States—which saw demonstrations in all the big cities greater than anything America had ever seen.

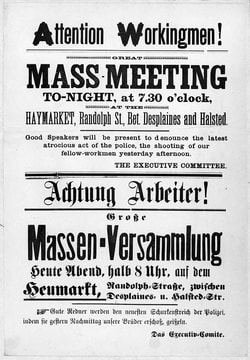

A peaceful rally took place that evening, with speeches from Parsons and other labor leaders condemning what had happened the night before. A light rain began to fall as the meeting neared its end, and most people began to head home. Without warning, a force of some 200 police officers charged the square. A fight broke out between the cops and the crowd, and then, suddenly, a bomb was thrown. A number of police officers were killed by the explosion. Volleys of police bullets then plowed through the terrified and fleeing audience, killing at least four workers and wounding scores.

Parsons, along with several fellow organizers, were rounded up and charged with being an “accessory to murder.” Prosecutors eagerly followed advice given by the New York Times to “pick out the leaders and make such an example of them as would scare others into submission.” A Chicago newspaper was even more blunt, with editors writing, “The labor question has reached a point where blood-letting has become necessary.” The trial was a classic case of intimidation, perjury, and forgery. The prosecution quickly gave up any attempt to prove that the men charged had thrown any bombs. No, the defendants were guilty of a far greater crime. They had inculcated among workers a theory of social change and spread in America the fearful idea of class consciousness. Socialism on trial As he faced the gallows, Parsons told the world that it was not just himself and the other defendants who were on trial, but rather the ideas of socialism and workers’ power. He declared to the judge, “Socialism is simple justice, because wealth is a social, not an individual product, and its appropriation by a few members of a society creates a privileged class, a class who monopolizes all the benefits of society by enslaving the producing class.” Knowing history would absolve the leaders at Haymarket, Parsons spoke his last solemn words to the court: “They lie about us in order to deceive the people, but the people will not be deceived much longer. No, they will not.”

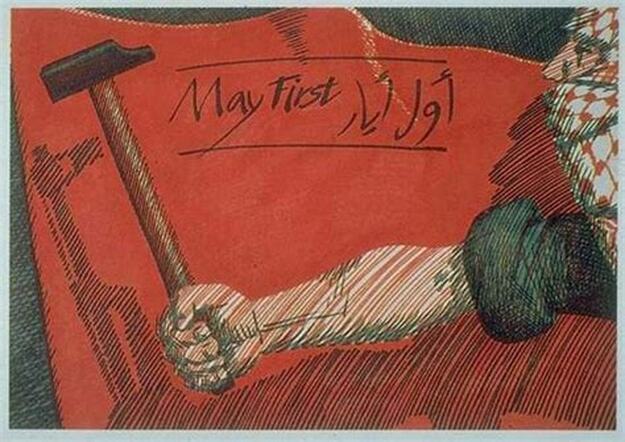

When the Second International, a global organization of socialist and labor parties, was founded three years later in 1889, it declared that May 1st would permanently be known as International Workers Day, in honor of the Haymarket struggle. Thus was born May Day—a global day of struggle and celebration—right here in the U.S.A. This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared as “Haymarket Hangings Vain Effort to Halt American Labor,” in the Nov. 12, 1937 edition of the Daily Worker. AuthorMilton Howard was the pen name of Milton Halpern, a correspondent for the Daily Worker (a People’s World predecessor publication). He served in the U.S. Army in Europe during World War II and was among those who liberated the Nazi death camp at Dachau. He was later an editor for Masses and Mainstream and was subjected to government harassment during the McCarthy period. This article was republished from People's World. Archives May 2022

1 Comment

In 1889, Clara Zetkin wrote: “Wherever busy folk are drudging under the yoke of capitalism, the organised working men and women will demonstrate on May Day for the idea of their social emancipation.” In today’s world, the murderous claws of oppression have dug deeper into the flesh of humanity. The globalization of capital, establishment of post-Fordist economic arrangements of flexible specialization, financialization of the accumulation process and neo-colonial strangulation of the Global South have led to a barbaric situation. Amid this generalized chaos, May 1 acts as a blazing streak, inviting the wretched of the earth to reflect intensively on their own history of joy, tenacious resistance, collective courage and strong solidarity. Old Roots May Day has old roots in archaic traditions of human responses to springtime and the customary pagan celebration of nature’s beauty and fertility amid spring’s full flowering in northern temperate zones. Dating to ancient Rome, this May Day is rooted in the seasonal rhythms of Earth and ecology. It reached across the Atlantic with the European conquest of the Americas. It is a day of leisure, to be spent outdoors, wearing flowers and soaking up the wind and sun. Dancing around maypoles, people enact a sense of participation in the joys of natural renewal and growth won back from winter’s death. It was an official holiday in the British Tudor monarchy by at least the early 16th century. The bourgeois Puritan Parliaments of 1649-1660 suspended the holiday, which was put back with the reinstatement of Charles II. Flames of Labor Militancy With the rise of capitalism, the ideas of the “Green May Day” merged with the “Red May Day” of Communists. Workers hailed May demonstration as a herald of future struggles, but also of future victories, which must as surely come as spring follows winter. While outlining the modern history of May Day, Rosa Luxemburg stated that it was born in Australia by workers - the stonemasons of Melbourne University - who in 1856 organized a day of complete stoppage together with meetings and entertainment as a demonstration in favor of the 8-hour day. The day of this celebration was to be April 21. At first, the Australian workers intended this only for the year 1856. But this first celebration had such a potent impact on the masses, that it was decided to repeat the celebration every year. The first to follow the example of the Australian workers were the Americans. At its national convention in Chicago, held in 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU) - which later became the American Federation of Labor - proclaimed that “eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labour from and after May 1, 1886.” The following year, the FOTLU, backed by many Knights of Labor locals, reiterated their proclamation stating that it would be supported by strikes and demonstrations. The anthem of the Knights of Labor was the “Eight-Hour Song”: “We want to feel the sunshine; On May 1, 1886, more than 300,000 workers in 13,000 businesses across the US walked off their jobs. In Chicago, the epicenter for the 8-hour day agitators, 40,000 went out on strike. Parades, bands and tens of thousands of demonstrators in the streets exemplified the workers’ strength and unity; the protests didn’t become violent as the newspapers and authorities had predicted. More and more workers continued to walk off their jobs until the numbers swelled to nearly 100,000, yet peace prevailed. It was not until two days later, May 3, 1886, that violence broke out between police and strikers. Lumber workers who were on strike for the 8-hour day were attending a meeting near the McCormick Reaper Works on the south side of the city, where 1,400 workers had been locked out since February and replaced by 300 scabs. When they went to confront the scabs at McCormick, the workers were attacked by some 200 police. 4 workers were killed and many others injured. The attacks continued into the following day, with police breaking up gatherings of workers. Full of rage, a public meeting was called by some of the anarchists for the following day in Haymarket Square to discuss the police brutality. In her autobiography, Mother Jones wrote: “All about were railway tracks, dingy saloons and the dirty tenements of the poor. A half a block away was the Desplaines Street Police Station presided over by John Bonfield, a man without tact or discretion or sympathy, a most brutal believer in suppression as the method to settle industrial unrest.” Due to bad weather and short notice, only about 3,000 of the tens of thousands of people showed up from the day before. As the meeting wound down, two detectives rushed to the main body of police, reporting that a speaker was using inflammatory language, inciting the police to march on the speakers’ wagon. As the police began to disperse the already thinning crowd, a bomb was thrown into the police ranks. No one knows who threw the bomb, but speculations varied from blaming any one of the anarchists, to an agent provocateur working for the police. Enraged, the police fired into the crowd. The exact number of civilians killed or wounded was never determined, but an estimated 7 or 8 civilians died, and up to 40 were wounded. An officer died immediately and another 7 died in the following weeks. Later evidence indicated that only one of the police deaths could be attributed to the bomb and that all the other police fatalities had or could have had been due to their own indiscriminate gun fire. Aside from the bomb thrower, who was never identified, it was the police, not the anarchists, who perpetrated the violence. Eight anarchists - Albert Parsons, August Spies, Samuel Fielden, Oscar Neebe, Michael Schwab, George Engel, Adolph Fischer and Louis Lingg - were arrested and convicted of murder, though only three were even present at Haymarket and those three were in full view of all when the bombing occurred. The jury in their trial comprised business leaders in a gross mockery of justice. The entire world watched as these eight organizers were convicted, not for their actions, of which all of them were innocent, but for their political and social beliefs. On November 11, 1887, after many failed appeals, Parsons, Spies, Engel and Fisher were hung to death. Lingg, in his final protest of the state’s barbarity, took his own life the night before with an explosive device in his mouth. The remaining organizers, Fielden, Neebe and Schwab, were pardoned six years later by Governor Altgeld, who publicly lambasted the judge for orchestrating a travesty of justice. Before being executed, Spies said: “If you think that by hanging us, you can stamp out the labor movement...the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil in want and misery expect salvation - if this is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but there and there, behind you and in front of you, and everywhere, flames blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out.” Internationalism The Second International, founded in 1889, took the initiative to internationalise May Day by giving it a revolutionary content. At the meeting of the Second International, a resolution was adopted to declare an international May Day. The resolution read: “A great international demonstration shall be organized for a fixed date in such a manner that the workers in all countries and in all cities shall on a specified day simultaneously address to the public authorities a demand to fix the workday at eight hours and to put into effect the other resolutions of the International Congress of Paris.” Instead of being confined to a demand for 8-hours working day, May Day became an instance of hope and struggle. In an April 1904 pamphlet, Vladimir Lenin wrote: “May Day is coming, the day when the workers of all lands celebrate their awakening to a class-conscious life, their solidarity in the struggle against all coercion and oppression of man by man, the struggle to free the toiling millions from hunger, poverty, and humiliation. Two worlds stand facing each other in this great struggle: the world of capital and the world of labour, the world of exploitation and slavery and the world of brotherhood and freedom.” Elizabeth Gurley Flynn said that May Day “obliterates all differences of race, creed, color, and nationality. It celebrates the brotherhood of all workers everywhere. It crosses all national boundaries, it transcends all language barriers, it ignores all religious differences. It makes sharp and clear, around the world, the impassable chasm between all workers and all exploiters. It is the day when the class struggle in its most militant significance is reaffirmed by every conscious worker.” May Day became an international socialist symbol of what the artist and designer Walter Crane called the “dawn of labour”. A Crane artwork for May Day 1896, for example, shows an English worker offering the hand of socialist cooperation to Italian, German, French and other workers with the slogan “International solidarity of labour - the true answer to jingoism”. Crane dedicated the work to “the workers of the world”. This May Day, it is important that we work to carry forward the noble aims of the Communist movement. No one captures these aims better than Crane. In his poem “The Worker’s Maypole”, he beautifully depicts the various threads of which May Day is composed: “World Workers, whatever may bind ye, AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Midwestern Marx's Editorial Board does not necessarily endorse the views of all articles shared on the Midwestern Marx website. Our goal is to provide a healthy space for multilateral discourse on advancing the class struggle. - Editorial Board |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed