|

9/11/2022 The Failed Serotonin Theory of Depression: A Marxist Analysis. By: Carlos L. GarridoRead NowA recent study published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry sent shockwaves across the scientific community and popular outlets as it disproved the predominant “serotonin hypothesis” of depression. In just two weeks since its publication it has been accessed by nearly half a million people and the subject of dozens of subsequent articles. The researchers analyzed a total of seventeen systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and other large studies focused on the following six tenets pertinent to the “serotonin hypothesis” of depression: “(1) Serotonin and the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA—whether there are lower levels of serotonin and 5-HIAA in body fluids in depression; (2) Receptors—whether serotonin receptor levels are altered in people with depression; (3) The serotonin transporter (SERT)—whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter in people with depression (which would lower synaptic levels of serotonin); (4) Depletion studies—whether tryptophan depletion (which lowers available serotonin) can induce depression; (5) SERT gene—whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter gene in people with depression; (6) Whether there is an interaction between the SERT gene and stress in depression.”1 None of the studies were able to prove any significant link between serotonin levels and depression based on the above tenets, leading the researchers to conclude that “there is no convincing evidence that depression is associated with, or caused by, lower serotonin concentrations or activity.”2 The researchers further argue, “The idea that depression is the result of abnormalities in brain chemicals, particularly serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT), has been influential for decades,” such that today “80% or more of the general public now believe it is established that depression is caused by a ‘chemical imbalance.”3 In light of this finding, one must ask—how did a hypothesis which failed to substantially prove the connection it is based on achieve such general acceptance? The serotonin hypothesis wasn’t always the dominant explanation for depression. Shortly after the Second World War, “the first antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was synthesized when chlorine was added to the promethazine structure.”4 This synthesis formed “the basis of the development of the first antidepressants” which emerged following Roland Kuhn’s 1957 presentation in the World Psychiatric Association Meeting, where shortly after the first tricyclic antidepressant was released for clinical use in Switzerland.5 A decade later, in the mid-1960s, a series of studies introduced serotonin as the “molecule behind depression.” These studies culminated in the work of Lapin and Oxenkrug, who postulated in 1969 the ”serotonergic theory of depression, which was based on a deficit of serotonin at an inter-synaptic level in certain brain regions.”6 In the following years, the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly created a serotonin-depression study team, which found that fluoxetine hydrochloride was “the most powerful… selective inhibitor of serotonin uptake among all the compounds developed.”7 The results led to the 1987 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the clinical usage of Prozac (the brand name given to fluoxetine), the first major selective serotonin receptor inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant drug.8 The release of Prozac revolutionized the commodification of medicine, incorporating a new field of mass advertisement which has since become the norm. However, as the documentary, Prozac: A Revolution in a Capsule demonstrates, the drug obtained its prominence not only through advertisement—which, interestingly enough, first occurred through business and finance magazines—but through its incorporation into culture as an iconic symbol of the zeitgeist.9 From Woody Allen movies to The Sopranos to late night talks shows, Prozac became the drug of the age, a commodity which, like Brave New World’s soma, could provide direct, unmediated happiness. This quickly resulted in the “Prozac boom,” making it by 1990 the most prescribed drug in the United States, and within ten years of its 1988 release, visits to the doctor for depression doubled and the prescribing of antidepressants tripled.10 The association of depression with low levels of serotonin was an intentional result of institutionally supported (e.g., American Psychiatric Organization) marketing campaigns from the pharmaceutical industry. This has provided “an important justification for the use of antidepressants” and perpetuated an antidepressant drug market that was valued at almost $16 billion in 2020 (a number expected to rise to $21 billion by the end of the decade);11 in today’s antidepressant epidemic, one in six Americans are on antidepressants.12 This phenomenon cannot be understood separately from the general commodification and marketization of medicine. As Joanne Moncrieff has argued, “there are some obvious drivers of this trend, such as the pharmaceutical industry, whose marketing activities have been facilitated both by the arrival of the Internet, and political deregulation, including the repeal of the prohibition on advertising to consumers in the US and some other countries in the 1990s.”13 This is how and why the serotonin theory gained and sustained its hegemony since the 1990s. However, within the scientific community this hypothesis has been on the chopping block for almost two decades as individual studies have disconfirmed various parts of the hypothesis. The scientific community, in general, is much more skeptical of the “serotonin hypothesis” than the general public. This disconnection between the much more nuanced science on depression and the public perception of the issue has been the subject of various articles and speaks to both the separation of science from everyday life and to the effectiveness of medical marketization.14 Nonetheless, the explosion the recent study caused is a result of its comprehensive character as an “umbrella review” which examined all parts of the serotonin hypothesis at once—and in doing so, went well beyond the many studies which have focused on separate parts in the last couple of decades. From Biochemical Determinism to Dialectical MaterialismThere is a prevalent myth which holds that those who function in society as professional “intellectuals” are somehow “autonomous and independent” from the dominant social order and the interests of the ruling class.15 This myth predominates in the community of the “hard” sciences perhaps more than in any level of traditional intellectuals. Here it is taken as sensum communem that science is objective and disconnected from ideology and social factors. For these folks, as Marxist scientists Richard Levins and Richard Lewontin said, “nothing evokes as much hostility… as the suggestion that social forces influence or even dictate either the scientific method or the facts and theories of science.”16 But it is in this illusion of non-ideological objectivity where ideology can be seen to be the most entrenched, functioning as unknown knowns, that is, as unrecognized assumptions or inherent biases which mediate how scientists approach the world. This does not mean, as the postmodernist disease17 which influences some of the philosophy of science holds, that we should maintain a “deep epistemological skepticism” which often, as Ellen Meiksins Wood notes, conflates “the forms of knowledge with its objects… as if they are saying not only that, for instance, the science of physics is a historical construct, which has varied over time and in different social contexts, but that the laws of nature are themselves ‘socially constructed’ and historically variable.”18 On the contrary, in Marxism, as Helena Sheehan argues, there is “no conflict between [stressing] the historical and contextual nature of science and [affirming] the rationality of science and the overall progressive character of its development.”19 In essence, the Marxist tradition’s understanding of the socially determined character of scientific production does not mean that scientific objectivity is rejected and that the object of scientific study itself is conceived of as relative. The form of abstract and unmediated objectivism which prevails in the sciences is rejected and what is affirmed is a necessarily socially mediated understanding of scientific objectivity. This overcomes, as Sheehan notes, the stale “objectivist/constructivist” binary which today structures the discourse about science and affirms instead a dialectical both/and attitude.20 This is important to clarify so that the forthcoming analysis of capitalism’s influence on science is not confused as an embracement of relativism and a rejection of science’s ability to produce objective knowledge of the world. The serotonin hypothesis emerges from what Levins and Lewontin called “Cartesian reductionism” (the objectivist extreme), which they held to be the “dominant mode of analysis” in all spheres of today’s sciences. In psychiatry this shows up as genetic and biochemical determinism, an attempt to reduce the complexity of mental health issues to genetics or to biochemical mechanisms which, with respect to the latter, somehow the major pharmaceutical companies always have a pill for. But, as Moncrieff has argued, “mental health problems are not equivalent to physical, medical conditions and are more fruitfully viewed as problems of communities or societies.”21 For instance, studies have shown that “within a given location, those with the lowest incomes are typically 1.5 to 3 times more likely than the rich to experience depression or anxiety.”22 The plethora of factors that stem from and contribute to poverty has allowed researchers to establish “a bidirectional causal relationship between poverty and mental illness,” such that poverty both increases the likelihood of mental illness and is proliferated further by it.23 The fact that the poorest in any context are up to three times more likely to experience depression than the rich shows that any analysis of depression must necessarily take into account the socioeconomic context of the individual. This inequality induced dissatisfaction allows one to understand both poverty and depression relationally. As Marx had already noted in 1847, Our desires and pleasures spring from society; we measure them, therefore, by society and not by the objects which serve for their satisfaction. Because they are of a social nature, they are of a relative nature… A house may be large or small; as long as the surrounding houses are equally small it satisfies all social demands for a dwelling. But let a palace arise beside the little house, and it shrinks from a little house to a hut… if the neighboring palace grows to an equal or even greater extent, the occupant of the relatively small house will feel more and more uncomfortable, dissatisfied and cramped within its four walls.24 The Cartesian reductive framework contains various methodological flaws which prevent the concrete understanding of the world. It treats, for instance, the interactions of parts and whole one-sidedly—as if parts are homogenous entities ontologically prior to the whole, and hence, as if the whole was simply the sum of its parts. In so doing, this outlook draws artificial hard and fast lines between causes and effects and fails to see how parts and wholes are reciprocally conditioning, i.e., how “their very interaction structures the way they are interrelated and interpenetrated, resulting in what is called a whole.”25 In short, how wholes are not simply the sum of their parts, but the totalities through which the parts themselves attain the functions which form the whole. It is, in essence, a methodological reflection in the sciences of bourgeois individualism and Robinsonade26 forms of thinking, which artificially divorce individuals from society and hold the latter to be simply the sum of the former. However, biochemical determinism/reductionism does not necessarily have to reduce explanations to only one factor. For instance, the inconsistent success of SSRIs27 in treating depression has led some scientists to sustain ex juvantibus28 (from reasoning backwards) that serotonin’s role in depression is interactive and dependent on its relations with adrenaline, dopamine, and other chemical processes. Although this represents a more complex view of the serotonin hypothesis in particular, and of the often wrongly conflated “chemical imbalance” view of depression, it is nonetheless a form of biochemical determinism.29 This is because it fails to see how the “chemical imbalances” don’t arise out of a void but are produced by the concrete environment the individual is in. The point, again, is not to diminish the biochemical in order to elevate the role of the environment, but to see both the biochemical and the environment as dialectically interconnected, acting “upon each other through the medium of the [individual].”30 As Levins and Lewontin argue, the individual “cannot be regarded as simply the passive object of autonomous internal (biochemical composition/genes) and external (environment) forces;” instead, the individual functions as a subject-object which is both conditioned by these factors (as object) and reciprocally conditions them (as subject).31 The limitations of the prevalent serotonin hypothesis also helps to demonstrate what Friedrich Engels noted in his unfinished Dialectics of Nature: although “natural scientists believe that they free themselves from philosophy by ignoring it or abusing it… they are no less in bondage to philosophy but unfortunately in most cases to the worst philosophy.”32 This reductive, bio-determinist outlook straitjackets science within abstract thought, preventing it from seeing things in their movements and interconnections. It forces the reduction of larger problems to simple components—since these are seen as the ontological basis of wholes—and limits the possibility of observing issues like depression dynamically and comprehensively. It is much easier to reduce depression to a biochemical phenomenon in the brain than to analyze how the social relations prevalent in the capitalist mode of life create the conditions for the emergence of depression. Similarly, once this reduction is established, it is much easier to treat the “solution” through individualized drug consumption than through socially organized revolutionary activity. As Moncrieff has argued, “by obscuring [the] political nature” of mental illness, certain “contentious social activities” are enabled, and attention is diverted “from the failings of the underlying economic system.”33 Tracing depression to the exploitative and alienating relations sustained between people and their work, their peers, and nature, is not only a much more laborious task, but one which would necessarily end in the realization of the systemic root of the problem. Given capitalism’s universal commodification, and the form this takes in what Levins and Lewontin call the “commoditization of science,” such a result is directly against the interests of the institutions that control scientific knowledge production.34 As one of many other fields in which the universalizing logic of commodity production has penetrated, the aim is, of course, profitability; the quest for truth and scientific discovery is subsumed under the quest for profit. This is especially true after four decades of neoliberalism, where, as Moncrieff notes, “more and more aspects of human feelings and behaviour” have been commodified and turned “into a source of profit for the pharmaceutical and healthcare industries.”35 “Investing in research,” as Levins and Lewontin argue, is but “one of several ways of investing in capital.”36 In the West, this reality was clear to the rich tradition of British Marxists scientists like J.B.S. Haldane, J.D. Bernal, Hyman Levy, and others which emerged following the 1931 Second International Congress of the History of Science and Technology. As J.D. Bernal stated in 1937, “production for profit can never develop the full potentialities of science except for destructive purposes,” only “the Marxist understanding of science puts it in practice at the service of the community and at the same time makes science itself part of the cultural heritage of the whole people and not of an artificially selected minority.”37 Towards Socialist Science and Medicine The serotonin theory gained prominence because: 1) it fits within the one-factor, causally linear framework of the Cartesian reductionist outlook prevalent in mainstream science; 2) it was a diagnosis which facilitated the greatly profitable solution embodied in the tens of billions of dollars’ worth antidepressant drug industry; 3) it plays a hegemonic role in steering the diagnosis of the depression epidemic away from its real source—capitalist social relations which sustain the mass of people alienated from what they produce, from other people, and from nature—and, specifically with respect to the United States, in drowning debt for getting sick, pursuing an education, or attempting to own a home. Socialism removes these material difficulties upon which many mental health issues are grounded and places the working class in control of the economy, state, and civil institutions, making them function in the service of human and planetary needs, not profit. By abolishing poverty and war; guaranteeing healthcare, housing, and education as a right for all; providing everyone with meaningful well-paying jobs; amongst other things, a socialist society creates the economic and social security which radically transforms the environment in which most cases of depression are rooted. If one seriously seeks to overcome the depression epidemic capitalism is hurling the mass of people into, socialism is the only real solution. Likewise, only socialism can de-commodify science and provide the general social atmosphere for a move away from a hegemonic outlook dominated by static, reductive, abstract, individualist, irrationalist, deterministic, and binary thought, and towards a dialectical materialist one which emphasizes change, interconnection, reciprocity, sociality, emergence, and concrete investigation of the concrete.38 The extraordinary successes of Cuban science and medicine testify to what can be done when the profit motive is removed and comprehensive, preventative, and community-based care becomes the norm. While enduring an internationally denounced blockade from the most formidable of empires, the Cuban revolution’s commitment to a science for the people has allowed it to construct what is internationally recognized as one of the best health care systems in the world.39 Cuba’s comprehensive social care emphasizes the impact of biological, social, cultural, economic and environmental factors on patients. Far from the United States’ drug-first approach of dealing with mental health issues, Cuba’s comprehensive social care allows all medical issues to be better understood at their source, treated, and prevented from occurring.40 In Cuba, mental health treatment emphasizes “individual and group psychotherapies” of various kinds,41 and when not hampered by the blockade, incorporates psychopharmacology in an integrated fashion with the former.42 Cuban scientists see mental health issues and treatment “within the context of the community,” not isolated individuals.43 As Alexis Lorenzo Ruiz, president of the Cuban Society of Psychology, said: “At all times, the community—like the family—are participants and necessary contributors in each action taken to move toward an improvement in the wellbeing of people with mental illness.”44 Additionally, unlike the disease-centered model of care which predominates in most capitalist countries, this human-centered approach promotes multidisciplinary and integrative relations between mental and medical care within the different fields of medicine—various forms of medical doctors, psychologists, nurses, and other health care professionals train side by side each other within the communities they serve in.45 This socialist model has afforded the Cuban people the conditions where, despite the enormous material difficulties created by the US blockade, depression in Cuba affects only 3.8 percent of the population, whereas in the United States 4.8 percent.46 In their 1985 book, The Dialectical Biologist, Levins and Lewontin reformulate Marx’s Eleventh Thesis and state that “dialectical philosophers have thus far only explained science. The problem, however, is to change it.”47 In the West, the seeds of such a change are emerging once again. As Nafis Hasan wrote in Science for the People, “recent developments in the fields of immunology, cancer, theoretical and evolutionary biology lend credence” to the view that “any non-reductionist approach (e.g., systems biology) to studying biology will advertently end up using a dialectical approach.”48 The fall of the reductive serotonin hypothesis in depression research is but one instance in many pointing to the fact that the dominant outlook presents a fetter for the development of the sciences. Just like a socialist revolution is needed to free humanity and the forces of production from the fetters of the capitalist system of waste, a revolution in outlook is needed to free the sciences from its archaic Cartesian reductionism and furnish it with “the most scientifically apt method for understanding the world”—dialectical materialism.49 Notes:

Originally published in Science for the People. AuthorCarlos L. Garrido is a Cuban American PhD student and instructor in philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale (with an MA in philosophy from the same institution). His research focuses include Marxism, Hegel, early nineteenth century American socialism, and socialism with Chinese characteristics. He is an editor in the Marxist educational project Midwestern Marx and in the Journal of American Socialist Studies. His popular writings have appeared in dozens of socialist magazines in various languages. Archives September 2022

0 Comments

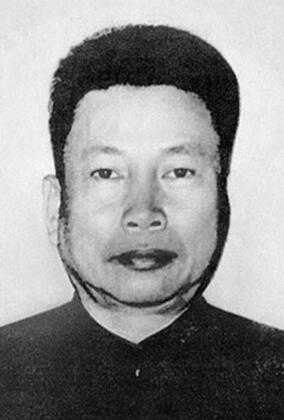

1/3/2021 BOOK REVIEW ESSAY: POL POT: ANATOMY OF A NIGHTMARE by Philip Short. Reviewed By: Thomas RigginsRead NowWho was Pol Pot and how did he come to symbolize one of the most horrible and repressive regimes in the history of modern times? The subtitle of Philip Short’s biography says it all-- a nightmare! Short knows his subject well, having been a reporter for the BBC, the “Times” (London) and “The Economist” and living in China and Cambodia during the 1970s and 80s. His book is more than a biography of Pol Pot. It is a history of modern Cambodia as well. He attempts to explain the rise and fall of the Khmer Rouge, also known as the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). As a Marxist, I was particularly interested in what Short had to say about the origins of the political party, the CPK, that Pol Pot headed. How could it be possible for a Marxist party to do what the Khmer Rouge did in Cambodia. That is, to be responsible for the killing one and a half million people-- at least-- 500,000 outright by mass executions of whole villages including women, children and old people and another million through malnutrition and disease. Could it be that the Khmer Rouge was not really a “Marxist” party at all? Was it possible that the CPK’s relation to “Marxism” was analogous to the relation that the National Socialist German Workers Party had to “Socialism” or Pat Robertson to “Christianity? That is to say, the word was used but it was empty of any of its traditional content. To me this was a distinct possibility as all the folks I know who consider themselves Marxists or Marxist-Leninists are repulsed by the actions of the Pol Pot government. I had read Jean-Louis Margolin’s essay “Cambodia: The Country of Disconcerting Crimes”, chapter 24 in The Black Book of Communism the new anti-communist Bible (and just as historical) and he maintains that the CPK is part of the history of the international communist movement. If Margolin was correct my theory would be insupportable. So, I read Short’s book with great anticipation to see if there was any evidence to support my thesis. Before going any further, let me define what I mean by “Marxism” or “Marxism-Leninsm,” and most especially what I consider a “Marxist” ( “Communist”) party to be. This is a definition based both on history and theory. Needless to say a Marxist or Communist party will have its program rooted in the theories of Marx, Engels, and Lenin as a minimum. It will be a party based on, and in, the working class and represent the material and spiritual interests of that class, especially its industrial component. It will be internationalist in outlook and represent the most historically advanced ideas based on an objective materialist and scientific outlook. According to these criteria, I would conversely consider a party to be in various degrees “anti-communist” in so far as it deviated from them. Since the term “anti-communist” has already been associated with the fascist movements and other right-wing political groupings, I will use the term “non-communist” or “non-Marxist” to describe ostensibly radical parties that fail to reflect the criteria expressed above. Now I will try to show, on the basis of Short’s research, that Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge associates were “non-communists” and in fact, their values and actions were diametrically opposed to the teachings of Marxism. That this is the case has been hinted at by the leadership of the Khmer Rouge. Consider the following statement by Ieng Sary (vice-premier) who claimed, quoted by Short, the Khmer Rouge would rule “without reference to any existing model” and would go where “no country in history has ever gone before.” They certainly did that! Margolin, in his anti-communist essay, writes: “The lineage from Mao Zedong to Pol Pot is obvious.” This is a superficial observation. Short argues that the Pol Pot regime morphed into what it became as a result of the cultural background unique to Cambodia. This cultural backdrop was the Khmer version of Theravada Buddhism “which teaches that retribution or merit, in the endless cycle of self-perfection, will be apportioned not in this life but in a future existence, just as man’s present fate is the fruit of actions in previous lives.” There was a “cultural fracture” between Khmer culture and the cultures of China and Vietnam, based as they are on Confucian values. Throughout the history of Cambodia this fracture has led to “mutual incomprehension and distrust, which periodically exploded into racial massacres and pogroms” by the Khmers against the Chinese and Vietnamese inhabitants of the country. Short presents a picture of Khmer society as having within it all the violence and brutality that the Khmer Rouge so horribly displayed. Previous movements and governments engaged in the same type of murder and mayhem that the Khmer Rouge indulged in-- the difference was one of magnitude. A case of quantitative change leading to qualitative change. Pol Pot and his associates were conditioned as children into Khmer culture (naturally) and when they joined in the nationalist and anti-colonial struggles of the 50s through the 70s they naturally allied themselves and identified with the Communist movements in Asia which were their only possible allies. But, as Short, points out: “Marxism-Leninism, revised and sinified by Mao, flowed effortlessly across China’s southern border into Vietnamese minds, informed by the same Confucian culture. It was all but powerless to penetrate the Indianate world of Theravada Buddhism that moulds the mental universe of Cambodia and Laos.” The Pol Pot leadership, made up of former students who had been educated in France as well as local anti-colonialist elements based themselves on the class of the poorest peasants and this was reflected in the ideology of the leadership. Here is Pol Pot talking about his “Marxism”-- “the big thick works of Marx... I didn’t really understand them at all.” Ping Say (one of the founders of the CPK ) remarked “Marx was too deep for us.” In fact, although influenced by their own version of “Marxism,” only two Cambodians ever attended the French CP’s school for cadres. For Pol Pot and his cronies “Marxism signified an ideal, not a comprehensive system of thought to be mastered and applied.” The tragedy that befell Cambodia was that a basically ignorant leadership gained control of the Cambodian revolution and carried out an atavistic racially based program against non-Khmer nationalities inside Cambodia as well as rooting itself in the values of the lower peasantry (abolishing money, formal education, traditional arts and technology). The policies of the US government, as well as those of China and Vietnam, helped this leadership come to power. The US aggression in Vietnam, as well as its attacks on Cambodia, were primarily responsible. In sheer numbers of people killed and mutilated the US aggression was twice as deadly as the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge. As for the support from China and Vietnam, it is only fair to point out that, as Short says, until 1970 Pol Pot had not done “or permitted to be done by the Party he led any intimation of the abominations that would follow.” But after Lon Nol overthrew the Sihanouk government (1970) the Khmer Rouge waged, with Chinese and Vietnamese help, a guerrilla war that eventually, after much bloodshed and indiscriminate killing (including massive bombing of civilians by the US) on all sides, led to their victory (1975). Short points out that, “The United States dropped three times more bombs on Indochina during the Vietnam War then were used by all the participants in the whole of the Second World War; on Cambodia the total was three times the total tonnage dropped on Japan, atom bombs included.” The US claimed to be bombing Viet Cong and Khmer Rouge troops, “but the bombs fell massively and above all on the civilian population.” But why were the Khmers so violent? Short maintains that the Chinese and Vietnamese communists treated their prisoners and enemies under the Confucian expectation that human beings are capable of change and reform. He also says that in Khmer culture there is no such expectation. Enemies will never change and have to be destroyed. “In the Confucian cultures of China and Vietnam, men are, in theory, always capable of being reformed. In Khmer culture they are not.” It was, as one Pol Pot’s bodyguards put it, a “struggle without pity.” After they came to power, the Khmer Rouge became xenophobic nationalists. Turning against the Vietnamese as the “hereditary enemies” of Cambodia they became anti-Vietnamese as Vietnamese of no matter what ideology. They also distrusted China and struck out on a path to be completely self-sufficient and dependent on no one (“independence-mastery” was the slogan). This is of course completely contradictory to any Marxist theory. Marxism stress internationalism and cooperation of fraternal and working class parties. It was that very internationalism which the Khmer Rouge banked on to get into power and which they immediately betrayed. What followed was disaster. By 1979 the Khmer Rouge had driven hundreds of thousands Vietnamese out of Cambodia and created a “slave state” at home. They finally began attacking across the Vietnamese border and this resulted in their being attacked in return and deposed from power. Earlier I quoted Ieng Sary to the effect of making a revolution that would be unique in history. He also said that theory was to be avoided and that the Khmer Rouge would just rely on revolutionary consciousness. In other words, they are a revolution now and will make their own reality. Short says this calls into question whether “Cambodian ‘communism’.... could be considered Marxist-Leninist at all.” I think it clear that it could not. Here is Pol Pot remarking that “Certain [foreign] comrades take the view that our party... cannot operate well because it does not understand Marxism-Leninism and the comrades of our Central Committee have never learnt Marxist principles.” His reply was that the CPK “did ‘nurture a Marxist-Leninist viewpoint’ but in its own fashion.” Its own fashion was not good enough. Short remarks that the “Cambodian Party had never been an integral part of the world communist movement... and it took from Marxism only those things which were consonant with its own worldview.” That worldview was narrow, insular and constricted and completely incompatible, I believe, with the ideas we usually, and properly, associate with the names of Marx, Engels and Lenin. After the Khmer Rouge were deposed by the Vietnamese, and the whole world could no longer pretend not to know what type of regime they had been running, how did that world react? The US, China, and the UN General Assembly sided with the Khmer Rouge and condemned the Vietnamese! As for the CPK, in 1981 it abandoned its claim to being a “communist” party and turned to the West and Sihanouk as allies. Pol Pot said “the communists are fighting us [i.e., the Vietnamese and the anti-Khmer Rouge Cambodians]. So we have to turn to the West and follow their way.” Short writes that this action by Pol Pot “provided confirmation, were any needed, that the veneer of Marxism-Leninism which had cloaked Cambodian radicalism had only ever been skin- deep.” Q.E.D. The rest of Short’s book continues the history of the Khmer Rouge to the death of Pol Pot and the final end of the movement in 1999. This is a book that should be read by everyone who wants to understand what happened to the Cambodian Revolution. It should also help to remind us that Marxism-Leninism is not just a name-- it is a working class movement not a movement to be dominated by petit bourgeois intellectuals and peasants. About the Author: Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. This article is a refurbished and republished version of one that appeared in Political Affairs Magazine in 2006.

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed