|

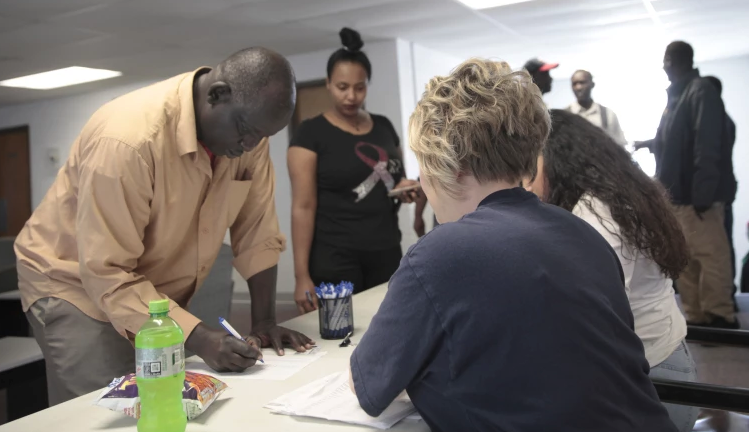

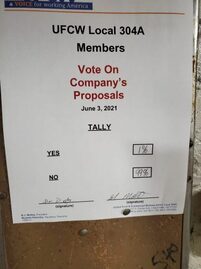

Smithfield workers on the line during the coronavirus pandemic. | Smithfield Foods SIOUX FALLS, S.D.—The workers at a huge meatpacking plant here with a history of caring little about whether they lived or died during the coronavirus pandemic defeated this month the company’s attempt to continue crushing them, this time with wage and benefit rollbacks. Worker determination to do anything and everything to protect their livelihoods became crystal clear on the night of June 7, when the members of United Food and Commercial Workers Local 204 voted 99% to authorize a strike against Smithfield Foods if the company did not agree to substantial wage hikes and to cease its attempts to slash health care and other benefits. For balking at the idea of making even more sacrifices for a company that endangered their lives and exploited them during the pandemic, they received little or no support from lawmakers, from Gov. Kristi Noem on down, who are beholden to the meatpacking industry. They received massive support, however, from the people in their own community, who turned out in car caravans to support them. Workers at the Sioux Falls Smithfield plant register to vote on the company’s contract offer, June 3, 2021. The members overwhelmingly against it. | Stephen Groves / AP The struggles of the people employed at the Smithfield plant in Sioux Falls began to intensify sharply at the beginning of the pandemic last year. Because of company refusal to protect workers and Trump administration refusal to do anything to force the company’s hand, the plant was the epicenter of one of the first major COVID-19 outbreaks in both the meat industry and the country as a whole. Of the 3,700 workers employed there, 1,294 were infected and four died, according to figures supplied by OSHA. In April 2020, the plant accounted for a large majority of total coronavirus infections in the state of South Dakota. The workers went home at the end of their shifts, where they then unwittingly infected members of their own families and their neighbors. Yet the governor did nothing to protect them or the other people in her state affected by the contagion originating from the plant. In fact, Noem threw up roadblocks when the town of Sioux Falls attempted to institute its own protective measures. Localities were forbidden from doing anything to protect their residents that the state as a whole was not doing. Yet the workers, led by their union and with strong backing from the South Dakota AFL-CIO, protested and managed to get the plant to temporarily shut down. Smithfield’s callous disregard for the need to protect its workers resulted in a plant early this month where hundreds were still out on long-term medical leave, according to reports from Local 304A President B.J. Motley. Despite the ruined health of many of its workers and the health problems widespread in the community because of Smithfield policy, the company announced this spring that it wanted $200-per-year increases in the out-of-pocket health care expenses paid by workers. On wages, the Smithfield pay of $17 per hour was already well below the industry standard, so a health cost hike would hit workers even harder. Workers, however, had another change in mind; they wanted the $19-per-hour wage paid at the nearby JBS meatpacking plant. The tally showing workers’ rejection of the company’s proposals, 99% to 1%. | UFCW Local 304A Considering everything, the UFCW made extremely reasonable requests. They basically only asked the company to rescind the demand for the extra $200 and to increase the starting wage to the same as it was at the nearby JBS plant. The company said during the pandemic that its workers were “heroes.” The media across the country joined in on nationwide proclamations calling frontline food service workers “heroes.” Suddenly, however, as far as Smithfield was concerned, its Sioux Falls workers had lost that status. “We’re not heroes anymore, are we?” a worker with nine years at the plant, Anthony Yesker, told the Associated Press. “They should at least look at the fact that we all put our lives on the line to keep the company going,” another worker said. It took bravery for the workers to take their strike vote. The last time workers at the Sioux Falls plant struck was back in 1987, when the company was still called Morell Meatpacking. In response to that strike, the company replaced half the workforce with scabs. Another demand from the company this time was that the unpaid leave allowances for workers be drastically reduced. This was seen as a direct attack on the hundreds at the plant who originate from West Africa and need to periodically return home to provide relatives with much-needed money. Only weeks after the strike authorization vote, Smithfield backed down completely on all of its demands and agreed to a starting wage of $18.75, just 25 cents below what the union had demanded. The company also agreed to a cash bonus of $520 for the workers. It’s not a huge amount of money for people who perform the dangerous, bloody work of cutting up hogs, but it was a solid if unexpectedly fast victory for workers who never had to go on the strike they had so overwhelmingly authorized. To help figure out why the workers were successful, People’s World talked with Kooper Caraway, the 29-year-old president of the South Dakota AFL-CIO. Caraway, known for his militant fights for worker rights, is the youngest AFL-CIO labor federation president in the nation. South Dakota AFL-CIO President Kooper Caraway “The fast and brave strike authorization vote was critical,” he said, “with the workers showing they were unafraid of company intimidation.” “Then it was a matter of picking a solid group of negotiators. It is important that workers and their unions send strong people to the negotiating table. Strong negotiators who are elected by the memberships to be strong negotiators will do much better when dealing with companies. Who you have at the bargaining table matters.” “Then it’s a matter of reaching out to the community,” Caraway said. The union movement appealed to the public in and around Sioux Falls, drawing the connection between the conditions faced by the workers and the people of the surrounding community. It worked well with huge car caravans of supporters turning out to back the workers. Caraway said that another key to the victory was the issue of solidarity. “The labor movement here has worked for years on the issue of solidarity among workers across nationality and national lines,” he said. The plant has Latino, Native American, West African, and white workers. One of the things that happened at Caraway’s urging soon after he was elected head of the Sioux Falls Central Labor Council several years ago was the establishment of an international solidarity committee at the plant itself. International labor solidarity was not at all high on the agenda of the old labor leadership Caraway and his backers replaced. Nor did they do much to grow the size and influence of the local labor movement itself with “organizing being limited basically to the annual Labor Day picnics,” according to Caraway. Solidarity: Outside the plant, members of the Sioux Falls community express their support for workers inside the Smithfield plant. | AP Caraway described what the new UFCW and labor federation leadership did at the plant. “We talked about the importance of being an active member of the union. There were discussions with workers about the need for all of the divergent groups to be united.” The unions organized the first ever Native American Day in Sioux Falls, attended and supported by all the other groups of workers and community members. “The result,” according to Caraway, “was the reduced ability of the company to divide and conquer people along lines of race and nationality.” He also described how action was taken to protect workers from bad forces inside their unions, including in any and all positions of leadership. “We passed an amendment to our constitution,” he said, “that forbids white supremacists and fascists from holding office in any of our member unions.” The militancy of an apparently invigorated labor movement in this part of the country, combined with unity among workers and backing from the community, seems to have yielded a much needed victory, at least for now, for the workers at the Sioux Falls Smithfield plant. AuthorJohn Wojcik is Editor-in-Chief of People's World. He joined the staff as Labor Editor in May 2007 after working as a union meat cutter in northern New Jersey. There, he served as a shop steward, as a member of a UFCW contract negotiating committee, and as an activist in the union's campaign to win public support for Wal-Mart workers. In the 1970s and '80s he was a political action reporter for the Daily World, this newspaper's predecessor, and was active in electoral politics in Brooklyn, New York. This article was republished from People's World. Archives June 2021

0 Comments

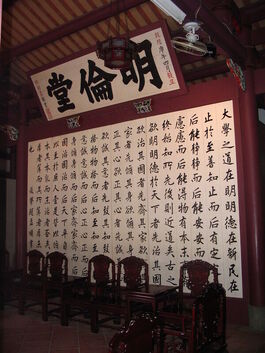

“Well Fred, I see you are ready to start our new discussion. You seem to have a lot of notes from the Chan book.” [Source Book in Chinese Philosophy] “That I do, Karl, but what is that big black book you have?” “This is very useful for anyone interested in Eastern philosophy. It’s edited by Ian P. McGreal and it’s called Great Thinkers of the Eastern World, published in 1995 by Harper Collins. It gives a good outline of the Great Learning and I thought I would go over it before we went over the actual text.” “That’s fine with me. It’s better sometimes to have an advance outline of what’s coming up before you read the actual text itself. What does your book have to say?” “This section is by Chenyang Li and he gives the Major Ideas in this book as the following: we have to look for the three aims and the eight steps.” “Yeah? Well, what are they?” “OK, ‘The three aims are manifesting one’s luminous virtue, renewing the people, and abiding in perfect goodness.’ While, ‘The eight steps are the investigation of things, extension of knowledge, sincerity of will, rectification of the heart, cultivation of the personal life, regulation of the family, national order, and world peace.’” “That sounds pretty good Karl.” “It would take ‘Great Learning’ indeed to do all this. But you know, making allowances for time and clime, these aims and steps could be adapted for our own times, of course with different cultural content in some instances.” “Now I’m going to turn to Chan, but feel free to break in with anything from Chenyang Li’s presentation whenever you feel like it.” “Thanks, I will.” “Chan points out that this work really became important in Neo-Confucianism, that is, in the Song Dynasty--that’s 960 to 1279 A.D.--so we have jumped several centuries into the future from our B.C. philosophers, but this is an old book, it was originally chapter 42 of the Book of Rites but now has an independent existence--its very short-- because the greatest of the Neo-Confucianist thinkers, Zhu Xi, 1130 to 1200 A.D., saw it as the epitome of Confucian thinking. As we said in a former discussion it became one of the Four Books as a result. The ‘three aims’ (Chan calls them ‘items’) and the ‘eight steps’, which make up this book, are called by Chan ‘the central Confucian doctrine of humanity “ren” [仁] in application.... The eight steps are the blueprints for translating humanity into actual living.’” “Now Fred, I want to bring up this observation. Zhu Xi was a really good Confucian because he wanted all the people to be educated. ‘Zhu Xi believed that the Great Learning was a text not only for the ruler, but for the common people as well.’” “It should be pointed out that the Chinese title, Da Xue, really means ‘adult education.’ Chan, in a note, says, ‘It means, therefore, education for the good man or the gentleman, or using the word in the sense of “great”, education for the great man.’” “I see, Fred. I also want to note that Zhu Xi thought this was the FIRST book to be read when beginning to study Confucianism, so we really messed up our discussion order!” “We should be ok, Karl, just think what a good background we now have!” “You’re right. Let’s get on with it!” “It gets a little complicated now, Karl, as the Confucianists emphasize learning but ‘have never agreed on how to learn,’ as Chan says. As a result, he writes, ‘the different interpretations of the investigation of things in this Classic eventually created bitter opposition among Neo-Confucianists. To Zhu Xi, ge-wu meant to investigate things, both inductively and deductively, on the premise that principle (li), the reason for being, is inherent in things. He believed that only with a clear knowledge of things can one’s will become sincere. He therefore rearranged the ancient text of the classic [oops!] to have the sections on the investigation of things appear before those on sincerity of the will. Wang Shou-jen, 1472-1529 A.D., on the other hand, believing that principle is inherent in the mind, took ge to mean “to correct,” that is, to correct what is wrong in the mind. To him, sincerity of the will, without which no true knowledge is possible, must come before the investigation of things. Therefore he rejected both Zhu Xi’s arrangement of the text and his doctrine of the investigation of things, and based his whole philosophy on the Great Learning, with sincerity of the will as its first principle.’” “Lets not get too far ahead of ourselves, Fred. After we do this discussion there are still several centuries to go before we get near to Zhu Xi and Wang.” “True enough. I’m going to start the Great Learning , Zhu Xi’s edition and with his ‘comments’ now instead of Chan”s.” “And of course with my pertinent interruptions with Chenyang Li!” “Of course!” “So, start!” “Here are the three aims: ‘The Way of learning to be great (or adult education) consists in manifesting the clear character, loving the people, and abiding (zhi) in the highest good.’ “ “I see that Chan’s translation is a little different than that in my book, Fred. This is one of the little inconveniences we will have to put up with. I don’t think it really hinders our understanding.” “No, it is easy to make these little translation adjustments. If there is a BIG difference in meaning we will certainly have to have a discussion about it. Shall I continue?” “By all means!” “’Those who wished to bring order to their states would first regulate their families. Those who wished to regulate their families would first cultivate their personal lives. Those who wished to cultivate their personal lives would first rectify their minds. Those who wished to rectify their minds would first make their wills sincere. Those who wished to make their wills sincere would first extend their knowledge.’ Now come the eight steps. ‘The extension of knowledge consists in the investigation of things. When things are investigated, knowledge is extended; when knowledge is extended, the will becomes sincere; when the will becomes sincere, the mind is rectified; when the mind is rectified, the personal life is cultivated; when the personal life is cultivated, the family will be regulated; when the family is regulated, the state will be in order; and when the state is in order, there will be peace throughout the world.’ And then follows a ‘democratic’ admonition that Mencius and all good Confucians would want to support. ‘From the Son of Heaven down to the common people, all must regard cultivation of the personal life as the root or foundation.’” “I would like to say that despite all the references to ancient Kings and sages we have been thus far exposed to, and taking notice of the objections to this made by the Legalists, it is obvious here that the Great Learning, and thus Confucianism, by stressing the extension of knowledge implies that old models are not really the best models. As knowledge is extended through the investigation of things then society as whole becomes more educated and the people and the state more perfected. This is a completely modern idea. One which the current quasi-Marxist Chinese state could well subscribe to. Chenyang Li says, ‘It should be noted that, in the Confucian view, the state is not a mechanism for balancing various pressure groups of conflicting interests. Rather, it is an enlarged family with mutual trust among its members.’” “What do you think of that Karl?” “It is wrong of course. But remember, this is the self-consciousness of the feudal elite living under a totally different type of class system than that produced over the last few centuries by industrial capitalism. States today are so obviously mechanisms for class rule that the Great Learning can not be taken at face value based on the outmoded views of the state that underlie it. Nevertheless, the essential philosophy it delineates can be adapted to modern times. I think, therefore, Confucianism can be harmonized with Marxism. They do not have to be antagonistic. Those Confucians who refuse to see this have turned their backs on the common people, the main concern of Confucius, and are just functioning as mealy mouthed spokespeople for continuing class repression. That's how I think at any rate.” “I’m almost sorry I asked! But here is a quote that sort of backs up your interpretation. ‘The Book of Odes says, “Although Zhou is an ancient state, the mandate it has received from Heaven is new” Therefore, the superior man tries at all times to do his utmost [in renovating himself and others.]’” “That’s ode 235 King Wen. He is the King who overthrew the Shang Dynasty. I have Arthur Waley”s translations [The Book of Songs, Grove Press., NY, 1996]. The ode also says, ‘By Zhou [Chou] they were subdued;/Heaven’s charge is not for ever.’ So if you don’t extend knowledge and renovate the people--look out!” “This is from chapter 6: ‘What is meant by “making the will sincere” is allowing no self-deception, as when we hate a bad smell or love a beautiful color. This is called satisfying oneself. Therefore the superior man will always be watchful over himself when alone.... For other people see him as if they see his very heart. This is what is meant by saying that what is true in a man’s heart will be shown in his outward appearance. Therefore the superior man will always be watchful over himself when alone.... Wealth makes a house shining and virtue makes a person shining. When one’s mind is broad and his heart generous, his body becomes big and is at ease. Therefore the superior man makes his will sincere.’” “This idea of sincerity is linked to the Confucian ideal of ‘humanity.’ A Confucian pursues ren with single-mindedness, self-cultivation and moral effort. Sincerity comes about by such single-mindedness and that leads to the self cultivation which allows for the perfection of ren. I remember this from Key Concepts in Eastern Philosophy by Oliver Leaman (Routledge, 1999).” “Good memory. Chapter 8 is a little bit hard for me to understand. ‘What is meant by saying that the regulation of the family depends on the cultivation of the personal life is this: Men are partial toward those from whom they have affection and whom they love, partial toward those whom they despise and dislike, partial towards those whom they fear and revere, partial towards those whom they pity and for whom they have compassion, and partial toward those whom they do not respect. Therefore there are few people in the world who know what is bad in those whom they love and what is good in those whom they dislike. Hence it is said, “People do not know the faults of their sons and do not know (are not satisfied with) the bigness of their seedlings.’” “I think it means that if one cultivates his or her own personal life, that is if he/she rectifies his/her mind according to Confucian philosophy then that person won’t be blinded by these partialities. We should note it was just these kinds of partialities that Mozi thought could only be eliminated by means of universal love, so he probably had the Great Learning in mind when he composed his own philosophy” (Cf Mozi Discussion). “Now for chapter 9: ‘What is meant by saying that in order to govern the state it is necessary first to regulate the family is this: There is no one who cannot teach his own family and yet can teach others. Therefore the superior man (ruler) without going beyond his family, can bring education into completion in the whole state.... (Sage emperors) Yao and Shun led the world with humanity and the people followed them. (Wicked kings) Jie and Zhou led the world with violence and the people followed them.[I think the context demands a ‘did not follow’ but you judge Karl.] The people did not follow their orders which were contrary to what they themselves liked. Therefore the superior man must have the good qualities in himself before he may require them in other people.... There has never been a man who does not cherish altruism (shu) in himself and yet can teach other people. Therefore the order of the state depends on the regulation of the family. The Book of Odes says, “His deportment is all correct, and he rectifies all the people of the country.” Because he served as a worthy example as a father, son elder brother, and younger brother, therefore the people imitated him.’” “Let us not forget that the large extended Chinese families of this time were very unlike our own shattered nuclear groups that have come about to facilitate the mobility of the workforce so necessary to the capitalist as opposed to the feudal system. That quote was from Ode 152 The Cuckoo which Waley renders as ‘The cuckoo is on the mulberry-tree; /Her young on the hazel./ Good people, gentle folk--/ Shape the people of this land./ Shape the people of this land./ And may they do so for ten thousand years!’ Besides a big difference in translation, I think it curious that the cuckoo should be selected as an example of a good family bird.” “Maybe it was a Confucian cuckoo.” “What’s next?” “We come now to chapter 10, the one explaining how to get world peace. ‘When the ruler treats compassionately the young and the helpless, then the common people will not follow the opposite course. Therefore the ruler has a principle with which, as with a measuring square, he may regulate his conduct.... The Book of Odes says, “Lofty is the Southern Mountain! How massive are the rocks! How massive is the Grand Tutor Yin (of Zhou)! The people all look up to you” Thus rulers of states should never be careless.’” “They don’t look up to Grand Tutor Yin with much hope, Fred. That is Ode 191 High-Crested Southern Hills and Waley renders the verse as: High-crested are those southern hills, With rocks piled high and towering. Majestic are you, Master Yin, To whom all the people look. Grief is burning in their hearts. But they dare not even speak in jest. The state lies in ruins, Why do you not see this? It appears that Grand Tutor Yin has been careless. The point is that rulers should be looking out for their subjects! When your cruelty is in full form, We will indeed meet your spears; But if you are constant and kind to us, Then we shall pledge ourselves to you.” “The Great Learning agrees with that. With respect to rulers it says, ‘by having the support of the people, they have their countries, and by losing the support of the people, they lose their countries. Therefore the ruler will first be watchful over his own virtue.” “This is obviously the source of Mencius’ view of the ‘Mandate of Heaven’ and his views on the right to remove bad rulers.” “Chapter 10 continues, ‘Virtue is the root, while wealth is the branch. If he [the ruler] regards the root as external (or secondary) and the branch as internal (or essential), he will compete with the people in robbing each other. Therefore when wealth is gathered in the ruler’s hand, the people will scatter away from him; and when wealth is scattered (among the people), they will gather round him. Therefore if the ruler’s words are uttered in an evil way, the same words will be uttered back to him in an evil way; and if he acquires wealth in an evil way, it will be taken away from him in an evil way.’ “This is very good advice. This is a practical handbook on how to rule and stay in power. Machiavelli is supposed to have composed the first such handbook, The Prince, and it’s pretty good, but the Great Learning isn’t that bad and I venture to say applying its maxims would keep one’s power just as well.” “It probably wouldn’t hurt to have them both on the nightstand.” “A good idea. One always needs a fall back position.” “This is next--its from the ‘Oath of Qin’ but, long before First Emperor. If First Emperor had been more aware of it Li Si would have been in hot water, he ultimately came to a bad end under the next emperor (executed by being cut in two at the waist). ‘In the “Oath of Qin” it is said, “Let me have but one minister, sincere and single minded, not pretending to other abilities, but broad and upright of mind, generous and tolerant towards others. When he sees that another person has a certain kind of ability, he is happy as though he himself had it, and when he sees another man who is elegant and wise, he loves him in his heart as much as if he said so in so many words, thus showing that he can really tolerate others. Such a person can preserve my sons, and grandsons and the black-haired people (the common people). He may well be a great benefit to the country. But when a minister sees another person with a certain kind of ability, he is jealous and hates him, and when he sees another person who is elegant and wise, he blocks him so he cannot advance, thus showing that he really cannot tolerate others. Such a person cannot preserve my sons, grandsons, and the black haired people. He is a danger to the country”’.” “This describes the relationship that came about between Han Fei and Li Si. One wonders if Han Fei had lasted (Li Si had him forced to commit suicide) and been an influence on First Emperor instead of Li Si, if the emperor would have behaved better and thus his empire would have outlived him for more than just a few years.” “I don’t know Karl. But, First Emperor obviously violated this last precept from the Great Learning, to wit, ‘To love what the people hate and to hate what the people love--that is to act contrary to human nature, and disaster will come to such a person. Thus we see that the ruler has a great principle to follow.’” “Or, as Machiavelli would say, This is what he must SEEM to follow. Now, if we have finished with the Great Learning, I want to suggest what we should go over next.” “Which is?” “Another one of the ‘Four Books.’ This one, also from the Book of Rites, is called the Doctrine of the Mean.” “OK, that’s next.” AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. To read the Confucius Dialogue click here. To read the Mencius Dialogue click here. To read the Xunzi Dialogue click here. To read the Mozi Dialogue click here. To read the Laozi Dialogue click here. To read the Zhuangzi Dialogue click here. To read the Gongsun Dialogue click here. Archives June 2021 Image: CPUSA. A socialist moment has sprouted up on the American landscape and is beginning to take firm root, as most recently evidenced by India Walton’s stunning victory in working-class Buffalo. While not yet a trend, Walton’s election continues the spate of left candidates’ victories in Congress, state legislatures, and city councils across the country, reflecting a deep discontent in the body politic. In a word, America is growing more radical. But what is the meaning of this word that falls so easily from our lips? Radicalization is an objective process born out of the class struggle and capitalist crisis. Yet, like all objective processes, it has subjective ripples. These eddies, while influenced by basic class conflicts, are not limited to them. As a result, different people are radicalized for different reasons. The environment, police violence, sexism, and other forms of gender discrimination, the treatment of animals, in addition to poverty, racism, immigrant rights, voter suppression, unemployment, and discrimination on the job can lead to folks seeking deeper, more radical solutions. In general, the communist movement welcomes the growing radicalization of the broad public, particularly its working-class majority. It means people are waking up. But after getting out of bed, do folks step to the right or to the left? This is an issue often dismissed as a “war over words,” since the word “radical” literally means “to the root.” But the roots, indeed, the entire tree of radicalization has many branches. And the winds of change blow them in myriad directions. Today, in bourgeois discourse, anything to the left or right of the political or religious center is often labeled “radical” by the ruling-class hegemony. This war of words should not be dismissed — it’s an important part of the ideological struggle. For example, in the mainstream media, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is often referred to as “radical,” along with the right-wing “radicals” who attacked the Capitol earlier this year. On the other hand, the Republicans in Congress attack Medicare for All for being a “radical socialist demand” while condemning Black Lives Matter marches as the product of “radical anarchism.” Here a class analysis is helpful in determining what’s really radical, that is, what actually goes to the root, and what doesn’t. For us, policies that get to the root of solving the problem of working-class exploitation and promote greater equality and democracy are radical. Simply put, those that don’t are not. Suppressing the vote isn’t radical — it’s deeply conservative. Neither is opposing marriage equality. On the other hand, proportional representation, a voting method that could greatly expand democracy for minority parties, is a positive, radical democratic demand. Historically, as capitalism became a world system and grew into imperialism, the radicalization of the broad working-class public led to the creation of what’s called the world revolutionary process. Frustrated and angered by inequality and exploitation, middle- and working-class forces formed unions and political parties to press forward their just demands and interests. The October Revolution was born out of this struggle and brought with it a new stage in the process, the period of the transition from capitalism to socialism. There is also a worldwide counter-revolutionary process at work that has led to world wars, as well as regional and local armed conflicts. It has promoted repression and the growth of fascism. U.S. imperialism is one of the leading, if not the leading sponsors. The Trump movement and its international counterparts are contemporary examples of these efforts. Notwithstanding important differences on domestic policy, the Biden administration’s policy toward China and Venezuela continues the anti-socialist drive. Today’s radicalization process is drawing millions . . . some toward revolutionary Marxism. On the other side of the class and democratic ledger, a deep and thoroughgoing radicalization process is at work today in the U.S. Beginning first with Occupy Wall Street, followed by the movements for Black lives and the mass protests led by women in the initial days of the Trump administration, today’s radicalization process is drawing millions into its various orbits, some of whom are, as if by the very force of gravity itself, drawn toward the working-class and revolutionary Marxism. It has crystallized in what we’ve called the socialist moment. Communists highly value the growth of these radical democratic trends. Their contributions, new ideas, and victories are very important. Those trends that gravitate toward the working class and Marxism are adding fresh forces along with new opportunities and challenges. One of the challenges is the growth in the influence of what might be termed “middle-class” or “petty bourgeois radicalism.” By middle-class radicalism is meant a rather eclectic set of ideas and practices that historically have their origins in this strata’s frustration and primitive rebellion. Pressed on all sides and stuck between capitalism’s two main classes, the petite bourgeoisie’s class aspirations are crushed time and again. Viewing the world from a frog’s perspective — always looking up — they are ever being pushed down into the ranks of the working class. Their political practices and outlook are largely shaped by these conflicted conditions of life. Absent the experience of working in large groups and being forced to collectively bargain, they tend to seek basic change along narrow, individual paths as opposed to seeing the need for moving masses in struggle, an outlook that lends itself to anarchism, individual acts of terrorism, and an unfounded confidence in the actions of small groups and self-styled “vanguards.” Some tend to be anti-corporate but not yet anti-capitalist, “anti-establishment” but out of touch with working-class needs, modalities, and political imperatives. Middle-class radicalism is a mass concept and political trend. As a result, these trends run up against and counter to the realities of struggle, a reality that is framed today by the broad democratic fight against the fascist danger. Mass electoral movements of both right and left are defining characteristics of these days and times, but the need to build political majorities for real change, particularly in the electoral arena, is largely lost on this trend, disdained in favor of allegedly more militant, revolutionary action such as abstract calls for general strikes regardless of whether or not the conditions for such important actions exist. Middle-class radicalism should be treated not so much as the expression of this or that individual or organization but rather as a mass concept and political trend, one that rises and falls in tempo with the class, democratic, and anti-imperialist struggles both domestically and worldwide. Needless to say, each episode brings with it the unique features of the political terrain on which it’s born. For example, after the defeat of the McCarthy period in the 1960s, the labor left was confronted with the growing influence of radical middle-class strata who were approaching but had not yet reached consistent working-class positions. These forces viewed Marxism-Leninism as old hat, the communist parties as outmoded, the working class as no longer revolutionary, unity an unrealistic watchword, and the class struggle a pipe dream. Inspired by the likes of Régis Debray, Herbert Marcuse, and others, they sought to forge a New Left, with new sources of revolutionary activity. Regarding their class backgrounds, CPUSA leader James E. Jackson wrote, “They have come to the party out of the non-proletarian classes … from the poor workers in agriculture and the urban petite-bourgeoisie — the students, the intellectuals, the professionals.” Applauding this development, Jackson also warned of potential conflicts: It is a welcome sign of the times that the petty-bourgeois militants — from the cities or countryside — enroll in movements of mass actions and the best among them come to the party. At the same time, they generate mass pressure and constitute the primary source for the current attacks upon vital features of the Communist Party’s policies in the spheres of ideology, organization and tactics. Today a new wave of radicalism is presenting itself in a climate quite different from the one that was confronted by Jackson and his comrades. Importantly, a new, New Left is once again emerging. The difference is that its roots now are closer to the working class and people’s movements. This is due, in part, to the class’s changing composition. Sections of the population once considered middle class have become “proletarianized,” that is, pushed into the working class. At the same time, a wider section of the working class have access to higher education and have become politically literate. Add to this the increase in women, people of color, and of course the growth in the service sector, and you have a very different situation indeed. Thus the problem today is not so much the influx of middle-class elements but the remaining influence, that is, the residue of petty-bourgeois ideology, a problem exacerbated by the relative weakness of the Marxist left and the growth of the internet. The impact of this residue should not be underestimated. With respect to ideological trends it reflects the ongoing impact of remnants of Maoism, Trotskyism, and to varying degrees strands of anarchism. What, then, are the main challenges presented by middle-class radicalism?