|

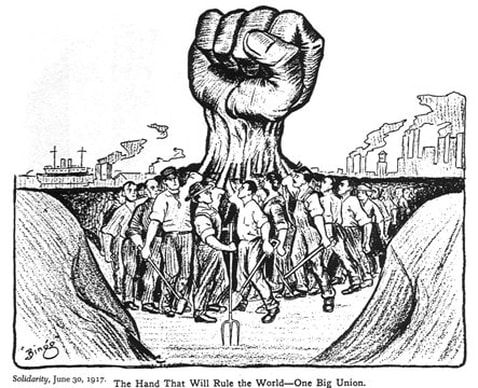

Cooperatives, enterprises where workers are the owners of their workplace, have always held an awkward place in the socialist movement. Proponents, such as Robert Owen, saw worker cooperatives as socialism in practice. Other socialists, such as Karl Marx criticized cooperative projects for being “utopian” in the sense that cooperative advocates sought to build a socialist society without first dismantling the existing order. Rosa Luxemburg’s critique of the cooperative movement best exemplified the thought among many Marxists, “The workers forming a co-operative in the field of production are thus faced with the contradictory necessity of governing themselves with the utmost absolutism. They are obliged to take toward themselves the role of capitalist entrepreneur—a contradiction that accounts for the usual failure of production co-operatives which either become pure capitalist enterprises or, if the workers’ interests continue to predominate, end by dissolving.” Mark and Luxembourg were not wrong. Take the Mondragon Corporation, which is the largest worker cooperative in the world, employing 81,507 people and generating 12 billion euros in revenue. But market pressures to maximize profits over the broader interests of the community have eroded Mondragon to adopt exploitative practices typical of a corporation. Today, only a minority of Mondragon’s workers are owners and the cooperative is infamous for suppressing labor unions in its foreign subsidiaries. As cooperatives became more profitable, the worker-owners started to lose their sense of solidarity with their fellow workers as their self-image takes on the contours of a small business owner. Are cooperatives fated to end up like Mondragon? A growing group of organizers and academics are firmly saying “NO.” Learning from the accomplishments and failures by previous socialist experiments, these activists are confronting the assumptions that cooperatives cannot dismantle the existing institutions of oppression, are anti-political, and suppress class consciousness. But before that, let’s talk about the other and larger socialist movement that has dominated much of the 20th century. The Social Democratic CenturyMost leftists agreed with Luxembourg and instead opted to join the social democratic movement. Unlike cooperatives, social democracy was perceived as political and militant. Social democrats believed the best path to abolish capitalism was by expanding the state bureaucracy through political parties and trade unions. The legacy of the New Deal era, a period of high union density and massive expansion of government programs, seemed to have validated those beliefs. But what followed social democracy wasn’t socialism, what followed was neoliberalism, also known as a 40-year bipartisan effort to undo every aspect of the New Deal from slashing taxes for the rich, weaponizing racist dog whistles as an excuse to gut welfare, and pass massive layoffs in the industrial heartland. In their book “Bigger than Bernie”, Jacobin contributors Meagan Day and Micah Uetricht argue that the revived socialist movement’s main priority should be to finish the New Deal. Day and Uectricht’s call to undo the last 40 years is best reflected in the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) national platform, which currently consists of building a rank and file labor movement, electing democratic socialists to office, and passing Medicare for All and a Green New Deal. Though Day and Uetricht acknowledge it’s simply not enough to rebuild the welfare state. As numerous historians have pointed out, a major cause for the downfall of the social democratic era was union bureaucrat’s suppression of militant labor organizers during the 2nd Red Scare. Day and Uetricht advocate for a supposedly revised version they call “class struggle social democracy.” The basic idea is that socialists should elect social democratic politicians and agitate for a militant labor movement at the same time. The assumption is that a militant labor movement can act as a check on social democracy’s tendency “to limit the scope and substance of the reforms which it has itself proposed and implemented, in an endeavor to pacify and accommodate capitalist forces." But organizing a militant labor movement isn’t new, it was actually the main strategy for social democrats in the 20th century. While the CIO leadership did try to contain the more radical sections of the labor movement, the labor federation still relied on militant actions to force concessions. In 1936, the United Auto Workers organized the famous Flint Sitdown Strike, even though the Wagner Act already created the National Labor Relations Court to mediate labor disputes the year before. Union bureaucrats containing more militant activists can only explain part of the decline of social democracy, a greater factor was the expansion of the professional-managerial class. A large reason why so many working-class households left the union hall for the cubicle was the level of education and experience many white-collar jobs required allowed those workers to negotiate higher wages without the need for a union. A New York Times article on Tom Harkin’s failed 1992 presidential run sums up how devastating the professionalization of America had an effect on the left, "The audience for Harkin's message is literally and figuratively dying," says Mike McCurry, the senior communications adviser to Kerrey. "It's just not appealing to the baby boomers, the geodemographic bulge that accounted for the Republican ascendancy of the 80's and that might signal a new Democratic resurgence in the 90's. These are people with virtually no party affiliations. The imagery of Roosevelt's New Deal simply does not resonate with them." A revived social democratic movement will only recreate this cycle of a generous welfare state expanding a professional middle class that would push for reforms that will then shrink the middle class and so on and so forth. But can the cooperative, that utopian experiment, provide a new path towards socialism? Cooperative activists correctly point out that worker-ownership reverses the dynamics between management and labor and thereby provide a much more radical transformation than expanding government programs and trade union density. Three case studies, one historical and two that are ongoing, provide evidence that cooperatives do not inherently have to cave to market forces but can act as a catalyst for social movements, and most importantly, by allowing people to experience a life where workers can own the means of production, they can counter the pressures to assimilate back to capitalism. The Populist Movement

The Civil War violently abolished America’s slave economy, but the war did not abolish crippling poverty for poor whites and emancipated slaves. The Civil War had accelerated America's industrial revolution. Slavery was not replaced with the Jeffersonian ideal of every man their own entrepreneur, instead, slavery was replaced with a more modern form of capitalism, the crop-lien system. Merchants known as "the furnishing man" by white farmers and "the man" by black sharecroppers, controlled the post-war cotton industry. The furnishing men ensured that farmers were perpetually kept in poverty by forcing farmers to pay exorbitant interest rates and seizing their crops as collateral or lien. By taking crops as collateral, the furnishing man reaped the farmer’s surplus. In response to what amounted to debt slavery, cotton farmers in the South and later corn and wheat farmers in the Midwest, organized cooperatives through the National Farmers Alliance to fight back against the crop lien system. Unlike previous cooperative societies, the populists were both confrontational and class-conscious. The populists inaugurated what Lawrence Goodwyn called, "the largest democratic mass movement in American history." Similar to a labor union, a farmer’s cooperative was a collective of farmers that allowed them to bargain with merchants for livable prices. According to Goodwyn, America’s founding ideology of meritocracy and rugged individualism forced farmers to create an entirely separate political tradition rooted in class warfare. The Farmers Alliance accomplished this feat by instituting a circuit of traveling lecturers who sought to replace the Jeffersonian myth of the farmer as the entrepreneur with an ideology that placed farmers and wage workers as members of the “producing class” being exploited by the financial monopoly. The growing class consciousness among farmers drove the National Farmers Alliance to seek an alliance with the labor movement through the Knights of Labor. According to one anti-union newspaper, the aid that farmers were giving to the Knights of Labor was integral to the Great Southwest Strike, “but for the aid strikers are receiving from farmers alliances in the state and contributions outside, the Knights would have gone back to work long ago.” However intense opposition by the railroad monopolies prevented the cooperatives from replacing the furnishing men, so the populists entered the political scene. In 1892, farmers formed the People's Party, the most successful third party in American history. The People's Party elected 11 governors, 35 members of the house of representatives, and six senators. But tragically, the populist movement does not have a happy ending. The People’s Party collapsed after their endorsed presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, lost to monopoly backed candidate, William McKinley. Bryan was not the populist’s first pick, he had actually refused to endorse the party’s most important demand, a radical transition of America’s monetary system from the gold standard to fiat money, a transformation we would not see until the 1970s. The populists also failed to dismantle America’s racial and regional divides, preventing the farmers from forming a strong alliance with black sharecroppers and northern industrial workers who became disorganized after the Knights of Labor dissolved. Worst of all, even after nearly two decades of fighting, the merchant and railroad monopolies were still intact, which took a huge toll on farmers’ morale. However, the remnants of the populist movement would later form the backbone for the burgeoning Socialist Party. Cooperative Jackson'“Politics without economics is symbol without substance”. This old Black Nationalist adage summarizes and defines Cooperation Jackson’s relationship to the Jackson-Kush Plan and the political aims and objectives of the New Afrikan People’s Organization and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement in putting it forward.' In the heart of the deep south, Chockwe Antar Lumumba, the socialist mayor of Jackson, Mississippi is promising to build "the most radical city on the planet." Lumumba and his father, the former mayor, also named Chockwe Lumumba, have been part of a decades-long fight to fulfill the Jackson-Kush plan, an ambitious promise to transform Jackson into a solidarity economy, a network of worker cooperatives, urban farms, and community land trusts. What may be most unique about Jackson-Kush is that it’s not rooted in the populist era cooperative movement or English mutual societies. Instead, Jackson-Kush is based on the ideology of pan-Africanism. The elder Lumumba, a veteran of the black power movement, was inspired by former Tanzanian president Julius Nyere’s theory of Ujamaa and Fannie Lou Hamer's Freedom Farms. Activists in Jackson began the movement by organizing the "People's Assembly." Taking inspiration from previous experiments in post-Katrina New Orleans, the People’s Assembly was a mass forum for citizens to address community issues, wage strategic campaigns to leverage pressure on political and economic decision-makers, and foster a culture of direct democracy. The assembly was incredibly effective in its goals, reaching 300 members by 2010. The People’s Assemblies were more than just a mechanism for direct democracy, they were a cultural revolution. Most city governments are run like personal fiefdoms, preserved through a system of patronage and party machines. The Peoples’ Assembly flipped that model by agitating the largely black and working-class population to become active decision-makers. The elder Chockwe channeled the politicization from the People’s Assembly towards an electoral landslide in 2013, winning the mayorship with 80 percent of the vote. Tragically, the elder Lumumba died only seven months into office. In 2014, Lumumba's son founded Cooperation Jackson, a grassroots organization committed to building a solidarity economy, which also became the base for Chockwe Antar’s successful 2017 election. However, relations between the mayor and activists started to sour. Lumumba drained the People’s Assembly of most of their top organizers and staff, which created a rift between city hall and the grassroots. Lumumba’s actions were partly in response to Mississippi’s white supremacist state legislature maneuvering to take away Jackson’s local control, including engaging in a tense legal battle with the city government threatening to take over the Medgar Wiley Evers Airport. Cooperation Jackson, the organization Lumumba founded, has started to focus on building the Jackson-Kush plan independent of the state. Cooperation Jackson’s possible shift away from politics risks the project eroding into the same pressures as Mondragon. However, Chockwe Antar Lumumba still has a working relationship with grassroots activists and against all odds is still pushing through with his promise to turn Jackson-Kush from a dream into a reality. It is hard to tell what the future holds for Jackson, Mississippi, but one thing is clear, only through the state will there be a transition to the solidarity economy. Democracy Collaborative“We on the Left can once again set about our historic task of constructing in earnest the kind of possible future world in which we’d actually want to live.” At the turn of the 21st century, a group of academics and activists created Democracy Collaborative to answer the criticisms that market forces will inherently erode cooperatives into a typical capitalist enterprise. Democracy Collaborative can't really be given a single label, it's a think tank, a business incubator, and a grassroots lobbying arm all-in-one. Their answer to the market pressure argument is a program they call "community wealth building." Under this framework, cooperatives are only one part of a larger economic system. The local community, through the state and NGOs, invest in worker-owned cooperatives, which are guaranteed employment through contracts with something known as "anchor institutions," businesses that are not going to be leaving the community. Most importantly, the decision-makers are not limited to the existing worker-owners but include the government, community leaders, and in some cases labor unions. It is important to remember that power and status in Mondragon is not determined by stratified educational levels and bargaining power, but by membership into the cooperative. Under Mondragon's structure, a worker-owner on Fagor's assembly line is more privileged than a programmer who was only an employee. Mondragon's erosion back to capitalist norms was caused by worker-owners excluding the next generation of membership, mutating worker ownership from a form of economic democracy into an exclusive club. By expanding the decision-makers beyond the worker-owner, community wealth building creates a check on worker-owners potential greed. To prove the viability of their model, Democracy Collaborative decided to test their model in Cleveland, Ohio. Cleveland is a textbook example of deindustrialization. Decades of neoliberalism, offshoring of manufacturing jobs, and white supremacist policy has turned Cleveland into one of the poorest cities in America. In 2010, the city government and several NGOs created the "Evergreen Cooperatives," which are three worker-owned cooperatives: Laundry, Energy Solutions, and Green City Growers. The Evergreen Cooperatives were deliberately set up in neighborhoods with a median income of $18,500, a disproportionately large undereducated workforce, and an unemployment rate of 25 percent. Evergreen also explicitly hired workers with prior felony charges. The cooperatives were guaranteed a contract with local anchor institutions, such as the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals. Like any new business, there were some early mistakes. The cooperatives had an overambitious target of 1000 employees and the lack of financial literacy among workers forced the cooperative to adopt a more representative model of governance. However, within a decade, Evergreen has grown to more than 100 workers, 30% of whom are already worker-owners. Two out of three of the cooperatives are profitable, with Green City Growers on track to profitability. Currently, only 15% of the revenue comes from the original anchor institutions. Keep in mind, this is all inside one of the poorest and under-invested-in cities in America. Through Community Wealth Building, Democracy Collaborative reversed the neoliberal norm of cities begging for corporate contracts by cutting public services. But Democracy Collaborative was never satisfied with merely proving there is an alternative to the status quo. During a Q and A session at Cornell College, Thomas Hanna elaborated that Evergreen is only a proof of concept, the main vision is to directly transition existing businesses and industries, from Amazon to Wall Street. Democracy Collaborative has intensely lobbied politicians, political parties, and organizers towards this program. Already the Bernie Sanders 2020 presidential campaign, the UK Labour Party, and People's Action, a million-member community organizing network, have all adopted the community wealth building framework. Community wealth building should not be seen as a “startup incubator”, but a spiritual successor to Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs vision for "the whole of all industry to represent a giant corporation in which all citizens are shareholders and the state will represent the board of directors acting for the whole people." ConclusionWhat the three case studies have shown us is that the answer to Luxembourg’s criticisms is not to abandon the cooperative, the answer is to integrate cooperatives into militant social movements. Each case study has directly challenged the existing order, actively engaged in the political sphere, and created an alternative analysis of the dominant narrative. The populists built agrarian cooperatives to organize a militant social movement and politicize farmers. Cooperation Jackson’s plan for a solidarity economy became the basis for a successful political campaign and created a radical vision of black self-determination. Democracy Collaborative proved that cooperatives do not have to succumb to market forces. More importantly, the three case studies are causing many leftists to question if the distinction between cooperative projects and social democracy still matters. Nationalizing key industries does not inherently contradict the cooperative’s effort to expand workplace and economic democracy, if anything they complement each other. Thomas Hanna recently published “Our Commonwealth,” where he argues for expanding public ownership through publicly owned enterprises in red states, such as the North Dakota Public Bank. Bernie Sanders' 2020 labor platform included a promise to force large corporations to divert 20 percent of their stock to an ownership fund democratically controlled by workers, itself influenced by the Meidner plan, a policy proposed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party in the 1970s. The Marxist economist, Richard Wolff, maybe right when he called cooperatives “Socialism in the 21st century.” About the Author:

Greg Chung is a Korean-American, born in New Jersey, but lived abroad for ten years in Vietnam and South Korea. He moved back to the states in 2018 to attend college in Iowa, where he became a community organizer for Iowa Student Action and later the Cornell College chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America.

4 Comments

Part 1: Presenting the ProblemThe movement towards worker cooperative has been a growing one as of the last couple decades. Although worker cooperatives can take various forms, they generally are companies in which the workers are also owners of where they work. They practice democracy at work, and seek to produce not for the goal of private capital accumulation in the hands of a single owner or small group of shareholders, but rather the earnings of the company are distributed and invested according to principles of the common good of everyone involved in the project. It has truly been a point of unification were socialist, communist, anarchist, radical liberals, and followers of catholic social teaching have all argued in favor of it as a more just form of enterprise structure to the traditional hierarchical capitalist firm. Beyond the fact that these coops are more just, practice has shown that they are usually more economically efficient and robust; the best current example is the Mondragon Corporation, founded by Father José María Arizmendiarrieta in 1956 in the Basque region of Northern Spain. There is a common misconception by some Marxist who speak about the promotion of cooperatives as un-Marxist. Their central argument is that a struggle for worker cooperatives while under capitalism is essentially an attempt to find Narnia; a magic door which in the other side you have a fictitious world of non-exploitative relations, where the central worker/owner dichotomy is destroyed. Their problem is essentially not with cooperatives in themselves, but rather with cooperative projects (and their promotion) under capitalism. They believe these projects distract from the class struggle and seek a way to find an alterative world within the real world, instead of changing the real world towards the alternative world we envision. Thus, the problem itself is not Narnia, but Narnia existing, as a strange loophole, within the non-Narnia world. My goal in this paper is to address this misconception and demonstrate that whether within or without a capitalist structure, worker cooperatives represent a reality that can be properly labeled as socialist. To do this, I will be referring to the thought the fathers of scientific socialism had on the topic. Not as an appeal to authority on the question of cooperatives, but to demonstrate how the Marxist rejection of worker cooperatives is based on a faulty appeal to authority. I will attempt to show how Marx, Engels, and Lenin all viewed worker cooperatives, both within capitalism or as an envisaged post-capitalist reality, as socialist. Before we begin, I feel it is important to address another false dichotomy about worker cooperatives and Marxist theorization of it. That is that it stands as an alternative to State centrally planned socialism. The phrasing of cooperatives as an “alternative” produces the idea that a socialist state can either be based on a cooperative economy, or one that is centrally planned by the state. This is not only theoretically but practically a false dichotomy. Cooperative ownership has been a major form of property in really existing socialisms. Specifically, it has had its major impact in the spheres of agriculture. During the initial loosening up of the blockade on Cuba by the Obama administration, Cuba opened up the possibility for non-agricultural cooperatives. These cooperatives instantly gained popularity and within just a year 452 of them developed,[1] playing an essential role in Cuba leading Latin America in 2015 with a GDP growth of 4.438.[2] The point is, there is already a strong cooperative past in really existing socialist states, a past which like Mondragon, helps us see the efficiency of cooperative ownership, within and beyond agricultural areas. This would demonstrate in practice that socialist experiments are not categorizable by the fixed set of categories of cooperative and state owned, given that both forms of property have coexisted successfully. It is also important to recognize this false dichotomy excludes other forms of property which are inherently anticapitalistic, and which exist and can help provide a base for socialist experiments. Such is the case of indigenous communal property, which Marx at the end of his life had already seen as having tremendous potential for the establishment of socialism in its struggle with the expansion of capitalism into those areas where those communal forms of property and mentality dominated. I have given a rough overview of how in practice cooperative forms of property have already been essential for socialist experiments. Although this topic is worthy of expansion, we will leave that for a latter work. In this work, I want to emphasize how theoretically the movement towards worker cooperatives is not the Narnia option certain unread Marxist might believe. Rather, that it presents within capitalism an internal negation of the system, and outside of capitalism, a real form of socialist property. Part 2: The Richard Wolff PhenomenaBefore we go on to discuss the framing of cooperatives by Marx and co. let us look at how American Marxist economist Richard Wolff presents the topic. In the US, Professor Wolff’s show Economic Update averages out well over 100,000 views on YouTube each episode. The YouTube channel itself, Democracy at Work, is named after their larger project and as of today is nearing the 200,000-subscriber mark.[3] His platform is without a doubt one of largest and most successful in the US (among Marxist spaces). And as can be inferred in the title of the project, the central focus is on the promotion of worker cooperatives and democracy at work as an alternative to the capitalist order. In the Economic Update episode of the 24th of August, Dr. Wolff examined the relation of cooperatives, socialism, and communism, clearer than in any other episode that I am aware of. This episode, which is called China: Capitalist, Socialist or What looks at the development of socialism in the USSR and in China. Dr. Wolff here uses Lenin to state that both the USSR and China are state capitalist. He does not do so in the way in which certain western ultra-leftist do it to dismiss these experiments as non-socialist, but rather he portrays the socialist step as itself state capitalism. To be clear, Lenin brings up state capitalism during the development of the New Economic Policy (NEP), which was meant to create the conditions, in an underdeveloped Russia, for the possibility of socialism under the will of a government already dedicated to the communist cause; as opposed to withdrawing from revolutionary action until capitalism had a chance to develop (the latter was the general stance of the Mensheviks and certain European communist observing the Russian uprisings). The point here is not to dive into Soviet or Chinese history and discuss whether they were state capitalist or socialist (a fixed categorizing dichotomy I believe to be inherently anti-dialectical and thus non-Marxist), but to look at how this generalization Dr. Wolff partakes in with statements Lenin made specifically for the NEP, paints the intermediary step of socialism as synonymous with state capitalism, and cooperatives as synonymous with the following communist step. On this topic of the transition away from capitalism and what one can call it, I think it is important to remember that as Marx states: “What we have to deal with here is a communist[4] society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally and intellectually, still stamped with the birth marks of the old society from whose womb it emerges.”[5] This quote and its analogy of the womb is quite intentional. It reflects the indestructible influence Hegel’s logic plays on Marx, specifically the dialectical categories of change (quantity and quality), and how every new qualitative transition never comes about from a void, it is always developed out and away from the previous qualitative structure. The comparison seems clear if we refer to Hegel’s Phenomenology, when in reference to the transition from a metaphysical world to a scientific one he states: “Just as the first breath drawn by a child after its long, quiet nourishment breaks the gradualness of merely quantitative growth, there is a qualitative leap, and the child is born, so likewise the spirit in its formation matures slowly and quietly into its new shape, dissolving bit by bit the structure of its previous world, whose tottering state is only hinted at by isolated symptoms.”[6] The point of this short diversion from the topic of coops, is to make a point to the other part of what Dr. Wolff’s episode was stating. I believe his disregard for the name calling of socialist states as socialist, state capitalist, or first stage communism, stems overall from his awareness that anything that grows out of capitalism and attempts to be something new, will always, at first maintain some elements of the previous world. This influence of the “old world” if you wish to call it that, is especially potent considering it really isn’t an “old world”, at least not yet; rather, capitalism exists in as an expanded a form as ever. It is very clear then, that any socialist attempt, will not be some pure utopia as some western ultra-communist wish to believe, it will necessarily maintain faults from the previous system. In part because it grew out of it, and in part because it is still subject to a world dominated by the logic of that which it outgrew. Part 2.1: First AnswerDr. Wolff is someone who is well aware that cooperative property has and still exists in socialist states. So why does it seem such a unique project to have a Marxist centered promotion of coops? Well, I think there might be two answers to this question, each which is connected to the other. First, it is obvious to anyone who has had the time to read the corpus of Marx and Engel’s work, that there is no blueprint for what a socialist economy would look like. We know that: “Between capitalist and communist society lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. There corresponds to this also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.”[7] But this isn’t really an idea of how to structure the society, it just tells us what is obvious to any socialist; that the working class must seize political power, and that once seized it must struggle to maintain it from the reactionary forces that will attempt against the qualitative leap. The most we really get is an idea of how the state transforms into an administrative force, an idea which comes from the example Marx and Engels witnessed in the Commune. As Engels states: “Against this transformation of the state and the organs of the state from servants of society into masters of society, an inevitable transformation in all previous states, the Commune made use of two infallible means. In the first place, it filled all posts, administrative, judicial, and educational, by election on the basis of universal suffrage of all concerned, subject to the right of recall at any time by the same electors. And, in the second place, all officials, high or low, were paid only the wages received by other workers. The highest salary paid by the Commune to anyone was 6,000 francs. In this way an effective barrier to place-hunting and careerism was set-up.”[8] Here we have two transformations, the first is a democratic transformation of the representatives of the people, elected and removed through universal suffrage. This might seem to overlap with bourgeois republics, where there are elections and to some extent the masses of working people have a say. But, as Engels mentions in the paragraph right before the one previously quoted[9], this bourgeois electoralism is faulty in it being still an instrument of the capitalist class, and thus, the apparent democratically elected officials not only represent the interest of the capitalist class that funds them but also partake in politics for the sake of careerism and self-improvement. The second transformation is done in an attempt to destroy the possibility of the previous political careerism; this is done through the paying of politicians and state officials average working-class salaries. Beyond this there is also the replacement of the institutions of state violence by armed groups of working people. As Marx states: “Paris could resist only because, in consequence of the siege, it had got rid of the army, and replaced it by a national guard, the bulk of which consisted of working men. This fact was now to be transformed into an institution. The first decree of the Commune, therefore, was the suppression of the standing army, and the substitution for it of the armed people.”[10] This means that the transformation of the state is the transformation from: “the democracy of the oppressor to the democracy of the oppressed classes, from the state as a “special force” for the suppression of a particular class to the suppression of the oppressors by the general force of the majority of the people, the workers and peasants.”[11] Quotes like the last few are found in numerous different places in the corpus of Marx and Engels’ work, the general idea is nicely summed up by Lenin as this “The transition from capitalism to communism certainly cannot but yield a tremendous abundance and variety of political forms, but the essence will inevitably be the same: the dictatorship of the proletariat.”[12] I would add here, that history has shown us that not only does this dictatorship of the proletariat, or proletariat democracy (whatever makes you feel more fuzzy inside), can not only yield an abundance of political forms, but also an abundance of economic forms, one of which is the worker cooperative form. Thus, why is there no blueprint? First, a blueprint of the structuring of socialist society would require details that would be nothing but foolish to predict. Secondly, a blueprint signifies a singular concept of socialist or communist organization. This would be an idealist generalization, that would fail to take into account the concrete material conditions in each country attempting to build socialism; in other words, a blueprint would be against the basic foundation of Marxist materialism. Thus, the only real requirement to considering a country as socialist is what is present in the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat; this is control of the state by the working class, with some aim towards a transitioning to a society based on the principle of “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs.”[13]The economic forms of property and political forms of structure that will develop are completely dependent on the concrete material and ideological conditions of the place where the development is coming about. Thus, we have the potential for socialism with Chinese, Cuban, Vietnamese, etc. characteristics. Each with their distinct variations of property forms and political structures, and to varying degrees moving away from the influences of their previous world. Part 2.2: Second AnswerMy second answer to the previously stated question concerning the seemingly uniqueness of Dr. Wolff’s push for cooperative socialism is that it is tactically the best strategy for achieving a post-capitalist reality in the US. The American population has endured a century of extreme anti-communist propaganda, and even though now, after 40 years of neoliberal rule and polarization of wealth, they realize the hell they are in, the psyche sickness the propaganda machine has caused will make any attempt at convincing working class American to fight for a post-capitalist reality impossible if done by means of discussing socialism in terms of a state controlled centrally planned economy. Discussing socialism in terms of democratization of the means of production, while nationalizing basic necessities and industries proves tactically the best path towards getting working class Americans on board. This is something that I have experienced as true in my practice organizing as well. If a working-class American asks me what socialism is, or why I am a socialist, and I respond by saying the dictatorship of the proletariat or a centrally planed state economy, they will never open up to the idea. In part, this is due to Americans equating anything done by the state as useless, and thus, a system run by the state just makes since that it will be no good. From their standpoint it is hard not to see a point, all the interaction they have had with the state has been with a state which represents a different class of people than the ones they are. It is no wonder they consider it inefficient; the American state is not supposed to be efficient for them, but rather for those who use it as an instrument for their accumulation of capital. The same capitalist class that sends their kids of to die, or comeback physically or mentally injured for the sake of their profiting from the imperial sacking of other nations. Thus, tactically, at least at first, socialism in America must be promoted through what it really is on the level of everyday life for working class folks. This is their expansion of power, autonomy, and life. It is promoting socialism as giving them a say in their workplace; them being able to decide what is made, how, when, to who it will be sold to, and for how much. It means them not having to worry about the company being shipped over sees for cheap labor to increase the profits of their bosses, but rather they themselves being their own bosses. It means the rational solution of eliminating the unnecessary middleman. They know they make the commodities exchanged all throughout society, or that they transport them making their exchange possible; they also know they are one paycheck away from homelessness while their non-working bosses’ life is so incredibly filled with luxury they can only get an insight into it when they turn on the TV. Thus, when you approach this worker, there is nothing theoretical you can tell him he doesn’t already feel. As Bill Haywood once said, “I’ve never read Marx’s Capital, but I got the marks of capital all over my body”. Big Bill’s statement still holds true today, perhaps truer now than in the last 50 years, given that the polarization of wealth we’ve seen has our society looking more like the 19th century than the 1950s. No longer are the 60s and 70s theories of the New Left, that consisted of how to make revolution without the working class because it was corrupted by its opportunist comfort viable for us today. If there was ever a time for revolution it is now. The accumulation is about to pop, the coming capitalist crisis, along with the pandemic, puts us in the ripe material conditions for this much necessary leap. As Lukacs states: “In this situation the fate of the proletariat, and hence of the whole future of humanity, hangs on whether or not it will take the step that has now become objectively possible.”[14] The question is now one of praxis. Which tactics are we using in our organizing spaces? This is where I think Dr. Wolff’s focus on coops comes in. As previously stated, the emphasis of socialism from the perspective of workplace democracy, and not state centrally planned economy, must be the angle we use in the US. It is the only angle the American worker is desensitized in, the concept of democracy, a concept so corrupted by the west it is unrecognizable to what it really means; yet it is the only one our workers are not put to fear by. Promote socialism in the US as the expansion of workplace democracy, and the guaranteeing of the essential rights of our population (something the US is the only developed country to not do), and we are guaranteeing ourselves the best shot at creating the subjective conditions which are necessary in such an objectively revolutionary time. Part 3: Marx, Engels, and Lenin on CooperativesIt is possible that the same type of ‘Marxist’ I referred to earlier is saying that I have not yet shown how promoting socialism as coops is in any way Marxist. It is possible that they see my previous tactical argument explaining the Wolff phenomena, merely as an attempt I am making to find that Narnia door, avoiding the class struggle and taking the easy path of classless enterprises under capitalism. This section necessitates its division into two parts. The first will be the question of cooperatives under a capitalist society. The second will be the question of cooperatives under a post-capitalist society. Part 3.1: Cooperatives in CapitalismIt might be easy to see the promotion of coops within capitalism the same way communist used to look at the hippie communes. Although the hippie commune and the coop are two completely different things, in the mind of the type of Marxist critics I have been talking about, both are clear example of escapism; a refusal to partake in the class struggle while retreating to a position in which the contradictions of capitalism are ameliorated in your everyday life. Like it usually happens with all falsehoods, there is always a kernel of truth. The kernel of truth here is that cooperatives do provide a sense of ameliorating capitalist contradictions, at least for those involved in the coop. With the removal of the boss figure, you have removed the contradiction of socialized production and individual accumulation. Where does the possibility of the transcending of capitalism go if we begin to ameliorate the contradictions for a portion of the population through the promotion of cooperatives? At the end of the day, it is true that radical liberals like John Stuart Mill and John Dewey promoted these forms of firms. Could cooperatives have been the capitalist loophole Marx was unable to see? The irony of the question is that it brings to mind Karl Popper’s objection of Marxism as a science; would the coop loophole prove to be the falsifier of scientific socialism? Before we appeal to Marx, I find it important to address this last point. This last point comes from a skepticism of coops’ status as socialism due to its acceptance as a form of property by those who do not necessarily seek to transcend capitalism. I think the duck test would work as a common sense respond to this worry. If something looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like one, you must be foolish to call it a chicken just because the guy next to you who has never seen a duck and is vaguely familiar with chickens, calls it a chicken. The point is, if a firm does not have the relation of owner and worker, if the process of production and distribution of wealth is taken into consideration collectively by those participating in the socialized production, and if the mentality is not the monadic rugged individualism of capitalism but rather a collective mentality in which the individual and collective interest are complimentary, then it’s a duck; to translated away from the analogy, it is not in any way, shape, or form a capitalist relation, but rather a form of production that transcends the relations and logic of capitalism. To reformulate the essence of the Marxist skepticism of coops, the skepticism lies usually not in the cooperative itself. Given that many if not all are able to recognize that it is not capitalist, and that a society purely based on cooperative firms with a working-class party in power could be called socialist. Their worry stems from the comfort the coop could bring about in a sector of the working masses, a comfort which might make the struggle against capitalism non appetizing for them, given that they are not really living the capitalist reality in their workplace. Their sentiment can be expressed nicely in Che’s proverb “we have no right to believe freedom can come without struggle.”[15] But what is being assumed when one states that a cooperative firm will bring the comfort to make possible the escape of capitalist conditions at work without struggle? Well, precisely this, that workers once they experience the comfort of a non-exploitative cooperative firm are going to retreat from the struggle against capitalism and enjoy their privilege condition as an anomaly within the system. This presupposes that the mentality of these cooperative workers is the same individualistic mentality capitalism promotes. The falsity here is that if there is something that worker cooperatives produces, more importantly than work without exploitation, is the fundamental mental shift away from the individualism of bourgeois society. A worker in a worker cooperative begins the epistemological transformation that would take place in the socialist phase, already within capitalism. This is a worker who is realizing his species essence as a being is dependent on the community, a being who comes to realize that: “Only in community with others has each individual the means of cultivating their gifts in all directions; only in the community, therefor, is personal freedom possible.”[16] The problem has been that many of these “Marxist” have focused a bit too much on the aspects of the economic side of Marxism. They call themselves scientific, as if in doing so they are looking down on the non-scientific or ethical based communist. They have forgotten to read the early Marx. They have forgotten that it was the humanist Marx that saw the need to study economics. They have forgotten that it was Marx the philosopher that saw the problem of alienation, traced it to its economic core, and then diverged the rest of his life to the study. So, yes, it is a science, but before the science begins we have a radical humanism, focused before anything on the abolition of the estrangement of man, and on the development of this man from his alienated condition to a condition re-united with his species being. And thus, the personal development the cooperative has on the individual, the source that refutes their conclusion of retreat from the struggle, slips the conscious of these Marxist. This is given to the fact that they have forgotten and neglected the most essential part of the development towards communism; the creation of the communist man, the man that has returned to his species being at a higher level than ever before because of the productiveness and abundance capitalism brings about[17]. This is the man the cooperative begins to develop; a man who will not only not stay put in his cooperative comfort, but who will fight with his life for his fellow man, to end their exploitation. This is a man who now has the concrete truth that a society based on equitable non exploitative productiveness is not only more just but efficient as well. Thus, the cooperative not only serves to develop the communist man that will be a secured catalyst in the struggle, but with it to develops the internal alternative that serves as a concrete possibility of the envisaging of a future beyond capitalism. So, what is it that Marx states about cooperatives within capitalism? There is essentially two things he says. First that: “The cooperative factories of the laborers themselves represent within the old form the first sprouts of the new, although they naturally reproduce, and must reproduce, everywhere in their actual organization all the shortcomings of the prevailing system. But the antithesis between capital and labor is overcome within them, if at first only by way of making the associated laborers into their own capitalist, by enabling them to use the means of production for the employment of their own labor. They show how a new mode of production naturally grows out of an old one, when the development of the material forces of production and the corresponding forms of social production have reached a particular stage. Without the factory system arising out of the capitalist mode of production there could have been no cooperative factories. The capitalist stock company, as much as the cooperative factories, should be considered as transitional forms from the capitalist mode of production to the associated one, with the only distinction that the antagonism is resolved negatively in the one and positively in the other.”[18] What is Marx saying here about cooperatives within capitalism? Well, that they essentially represent an internal negation to the system, the “new mode of production naturally growing out of the old”. This should remind us of his comments on the lower stage of communism from the Critique of the Gotha Program earlier, where the first stage of communism still has the birthmarks of the womb of the old society. It is also very important to understand what is being said in the last statement. “The only distinction that the one antagonism is resolved negatively in one and positively in the other”, what does this mean? Well, to understand what this means we need literacy in Marxist dialectics. To get a direct reference to help us understand this quote, we are going to travel back to 1845 and the publishing of his and Engel’s first major work, The Holy Family. In Ch. 4 Marx states: “Proletarian and wealth are opposite; as such they form a single whole. They are both forms of the world of private property. The question is what place each occupies in the antithesis. It is not sufficient to declare them two sides of a single whole. Private property as private property, as wealth is compelled to maintain itself, and thereby its opposite, the proletariat, in existence. That is the positive side of the contradiction, self-satisfied private property. The proletariat, on the other hand, is compelled as proletariat to abolish itself and thereby its opposite, the condition for its existence, what makes it the proletariat, private property. That is the negative side of the contradiction, its restlessness within its very self, dissolved and self-dissolving private property. The propertied class and the class of the proletariat present the same human self-alienation. But the former class finds in this self-alienation its confirmation and its good, its own power: it has in it a semblance of human existence. The class of the proletariat feels annihilated in its self-alienation; it sees in it its own powerlessness the reality of an inhuman existence. Within this antithesis the private owner is therefore the conservative side, the proletariat, the destructive side. From the former arises the action of preserving the antithesis, from the latter, that of annihilating it.”[19] Here, in the beautiful poetic dialectics of the young Marx, we find the key to understanding what his later self is saying in respects to stock companies and worker cooperative. In essence, stock companies represent the positive side of the antithesis, the side which seeks to actively maintain the existing capitalist relations. Therefore, worker cooperatives, represent the negative side of the antithesis, that being the side which strives for the annihilation of the existing relations as such. Thus, his view on cooperatives in capitalism is essentially that, like the proletariat itself, it represents the aspect of the dialectic seeking to abolish the condition of the existing order. It is a form of property in direct contradiction with private property as maintained under capitalism, and whose existence and growth represents a threat to capitalism itself. The second view Marx has on coops in capitalism is more so a tactical one. It comes from his Critique of the Gotha Program. His argument here is less optimistic, but when we analyze it closely, the loss of optimism about coops is one based on tactics, not cooperatives themselves. He states: “That the workers desire to establish the conditions for cooperative production on a social scale, and first of all on a national scale in their own country, only means that they are working to revolutionize the present conditions of production, and it has nothing in common with the foundations of cooperate societies with state aid. But as far as the present cooperative societies are concerned, they are of value only in so far as they are the independent creations of the workers and not the proteges either of the government or of the bourgeois.”[20]. What Marx is saying here is that if worker cooperatives are something promoted by the state or by the bourgeois class, there is no revolutionary value in them. Of course, under these conditions, the control over these experiments can very well lead to the comfort the previous mentioned Marxist might fear in coops. But, all in all, he is consistent with what he says in Capital Vol 3, by stating that if rather than being something promoted by the bourgeoisie or state it is something that grows out of the working class, then it is of revolutionary potential. This is to some extent a quite simple point, that is, only if this revolutionary action is truly an action of the revolutionary agent is it revolutionary. A sidestep to Lenin might help us better understand this point. Lenin states: “Why were the plans of the old cooperators, from Robert Owen onwards, fantastic? Because they dreamed of peacefully remolding contemporary society into socialism without taking account of such fundamental questions as the class struggle, the capture of political power by the working-class, the overthrow of the rule of the exploiting class. That is why we are right in regarding as entirely fantastic this “cooperative: socialism, and as romantic, and even banal, the dream of transforming class enemies into class collaborators and class war into class peace (so called class truce) by merely organizing the population in cooperative societies.”[21] Again, the only objection here is the promotion of cooperatives as some sort of hippy commune thing which tries to alienate itself from the class struggle. But, given that exploitation will be a reality around the cooperative workers, and given the transformation they will have in their consciousness, it is indubitable that the class struggle will remain a central focus of the cooperative worker. When coops are used as fellow instruments in the class struggle, when they play their role as the negative in the whole, and if they help achieve power for the working class; then there is nothing else one can consider them but properly socialist. As Lenin states: “Now we are entitled to say that for us the mere growth of cooperation is identical with the growth of socialism, and at the same time we have to admit that there has been a radical modification in our whole outlook on socialism. The radical modification is this; formerly we placed, and had to place, the main emphasis on the political struggle, on revolution, on winning political power, etc. Now the emphasis is on changing and shifting to peaceful, organizational, cultural work.”[22] What is this cultural shift Lenin touches on at the end, if not precisely the development of man, the one that develops during and with cooperative work, and which to some extent is even required before taking upon the cooperative project. Thus, Lenin states “the organization of the entire peasantry in cooperative societies presupposes a standard of culture”[23], this holds the key to understand the statement by Marx and the source of the cooperative. If the cooperative is started by workers, it is because they have already a level of consciousness, or what Lenin here calls culture, that is essential in determining the revolutionary status of the action. But, if the cooperative is promoted by another source that is not workers, the conscious or cultural element, has failed to precede the cooperative formation, and thus the formation itself cannot be deemed revolutionary. But, when one agitates workers, and helps them realize their common interest in cooperative firms, in democracy at work, and then they take up the revolutionary action of creating cooperatives and continuing the class struggle; what is this if not precisely a revolutionary action, the manifestation of the internal negative. Thus, the promotion, differs from the creation. Promoting worker coops and having workers form them can be seen as revolutionary action. While a state or capitalist formed cooperative where workers are employed cannot be considered as a revolutionary action in itself, even though it definitely can, by its very nature, develop a revolutionary potential. Part 3.2: Cooperatives in SocialismThis section is bound to be short, as it is obvious to any communist or socialist, that in a socialist society, a worker cooperative is in line with the ideals of the society. The difficulty was in the previous section, in address the question of withdrawal from the class struggle. Now that we have overcome that, there seems to be little rejection of cooperatives as a positive form of property under socialism. Regardless, I will fulfill my promise of providing what the fathers of scientific socialism had to say on the topic. The clearest response to a fully cooperative society comes from Marx. The context of which is in discussion with he who calls a duck a chicken; that being the bourgeois political economist who promotes cooperative firms[24]. Marx states that: “Why, those members of the ruling classes who are intelligent enough to perceive the impossibility of continuing the present system, and they are many, have become the obtrusive and full-mouthed apostles of cooperative production. If cooperative production is not to remain a sham and a snare; if it is to supersede the capitalist system; if united cooperative societies are to regulate national production upon a common plan, thus taking it under their own control, and putting an end to the constant anarchy and periodical convulsions which are the fatality of capitalist production, what else, gentlemen, would it be but communism, “possible” communism?”[25] The quote speaks for itself, what is a fully cooperative society? Quite simply communism. You can call it whatever you want, it is what it is. Let us turn to Engels now, as in a letter to Bebel he states: “My proposal envisages the introduction of cooperatives into existing production, just as the Paris Commune demanded that the workers should manage cooperatively the factories closed down by the manufacturers.”[26] He then states that neither Marx nor he had: “ever doubted that, in the course of the transition to a wholly communist economy, widespread use would have to be made of cooperative management as an intermediate stage.”[27] We will end with Lenin, who states that: “Given social ownership of the means of production, given the class victory of the proletariat over the bourgeoisie, the system of civilized cooperators is the system of socialism.”[28] “cooperation under our conditions nearly always coincides fully with socialism.”[29] ConclusionIn this work, I hope to have demonstrated the following, 1- that cooperatives within capitalism represent a negation of the system and help promote socialism in two ways. The first is by the development it produces in its workers, the second is by the example it gives to the rest of society of the “proof that the capitalist has become no less redundant as a functionary in production as he himself, looking down from his high perch, finds the big landowner redundant.”[30] 2- I hope to have shown that a society based on cooperatives can properly be called socialist. And 3- That tactically the promotion of socialism as cooperative or workplace democracy is the route we should pursue in our engagements and organizing of workers in America. Citations and Side Comments.[1] Rodriguez Delli, Livia. “Cooperativas no agropecuarias: de una experiencia a una novedad en Cuba” Granma, April 30, 2014. http://www.granma.cu/cuba/2014-05-19/cooperativas-no-agropecuarias-de-una-experiencia-a-una-novedad-en-cuba?page=4

[2]GDP growth (annual %) – Latin America & Caribbean, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, Peru, Cuba. The World Bank, 2015. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2015&locations=ZJ-CO-CL-MX-PE-CU&most_recent_year_desc=false&start=2015&view=bar [3] Wolff, Richard. Democracy at Work, September 7, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/user/democracyatwrk [4] It is important to note here that Marx uses communism and socialism interchangeably. Specifically, in this work he refers to the difference as the first or lower stage of communism and the higher stage. The higher is the state in which things would be carried out “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!” Marx, Karl. “Critique of the Gotha Program” The Marx-Engels Reader (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978/1875), p. 531. [5] Ibid., 529. [6] Hegel, G.W.F. Phenomenology of Spirit (Oxford, 1977/1807), p.6. [7] Marx. Critique of the Gotha Program. p. 538. [8] Engels, Frederick. “The Civil War in France: Intro” Marx-Engels Reader (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978/1891), p.628. [9] “Nowhere do “politicians” form a more separate and powerful sections of the nation than precisely in North America. There, each of the two major parties which alternately succeed each other in power is itself in turn controlled by people who make a business of politics, who speculate on seats in the legislative assemblies of the Union as well as of the separate states, or who make a living by carrying on agitation for their party and on its victory are rewarded with positions. It is well known how Americans have been trying for thirty years to shake of this yoke, which has become intolerable, and how in spite of it all they continue to sink ever deeper in this swamp of corruption. It is precisely in America that we see best how there takes place this process of the state power making itself independent in relation to society, whose mere instrument it was intended to be. Here there exists no dynasty, no nobility, no standing army, beyond the few men keeping watch on the Indians, no bureaucracy with permanent posts or the right to pensions. And nevertheless we find here two great gangs of political speculators, who alternately take possession of the state power and exploit it by the most corrupt means and for the most corrupt ends, and the nation is powerless against these two great cartels of politicians, who are ostensibly its servants, but in reality dominate and plunder it.” Ibid., 628. [10] Marx, Karl. “The Civil War in France” The Marx-Engels Reader (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978/1871), p.632. [11] Lenin, V. I. The State and Revolution (Foreign Language Press, 1970/1917), p. 36. [12] Ibid., 29. [13] Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program. p. 531. [14] Lukacs, Georg. History and Class Consciousness (MIT Press, 1979/1923), p.75 [15]Guevara, Che. “Message to the Tricontinental” Che Guevara Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/guevara/1967/04/16.htm [16] Marx, Karl. “The German Ideology” The Marx-Engels Reader (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978/1932), p. 197. [17] Part of the reason why Marx changes his position on Europe being the center for revolution is because even at the beginning of the 1880’s he still saw the tremendous role the subjective element of man played. Thus, when studying the anthropologist at the time, Henry Morgan, Kovalevsky, etc. he realizes the potential indigenous communities have towards the building of the higher stage of communism. The potential stems from them having never lost their collective mentality. Thus, whereas the proletarian in Europe had to develop his consciousness before any material struggle could take place, the communards of the colonized global south already had that “communist consciousness” and thus from the beginning their struggle is already an ideologically conscious one. [18] Marx, Karl. Capital Vol 3 (International Publishers, 1974/1894), p. 440. [19] Marx, Karl. The Holy Family (University Press of the Pacific, 2002/1845), p.51. [20] Marx, Karl. Critique of the Gotha Program. p. 536-7. [21] Lenin, V. I. “On Cooperation” Collected Works, Vol 33 (Progress Publishers, 1965), p.473. [22] Ibid. [23] Ibid. [24] This response is believed to be an indirect jab at John Stuart Mill’s conception of capitalism heading down the road to cooperative firms. [25] Marx, Karl. The Civil War in France. p. 635. [26] Engels, F. 1886. Letter to Bebel, 20-23 January, in Marx-Engels, Collected Works, Vol. 47. Quoted from Jossa, B Marx, Marxism, and the Cooperative Movement. (Cambridge Journal of Economics, 2005) [27] Ibid. [28] Lenin, V. I. On Cooperation. p. 472. [29] Ibid. [30] Marx, Karl. Capital Vol 3, p.387 |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed