|

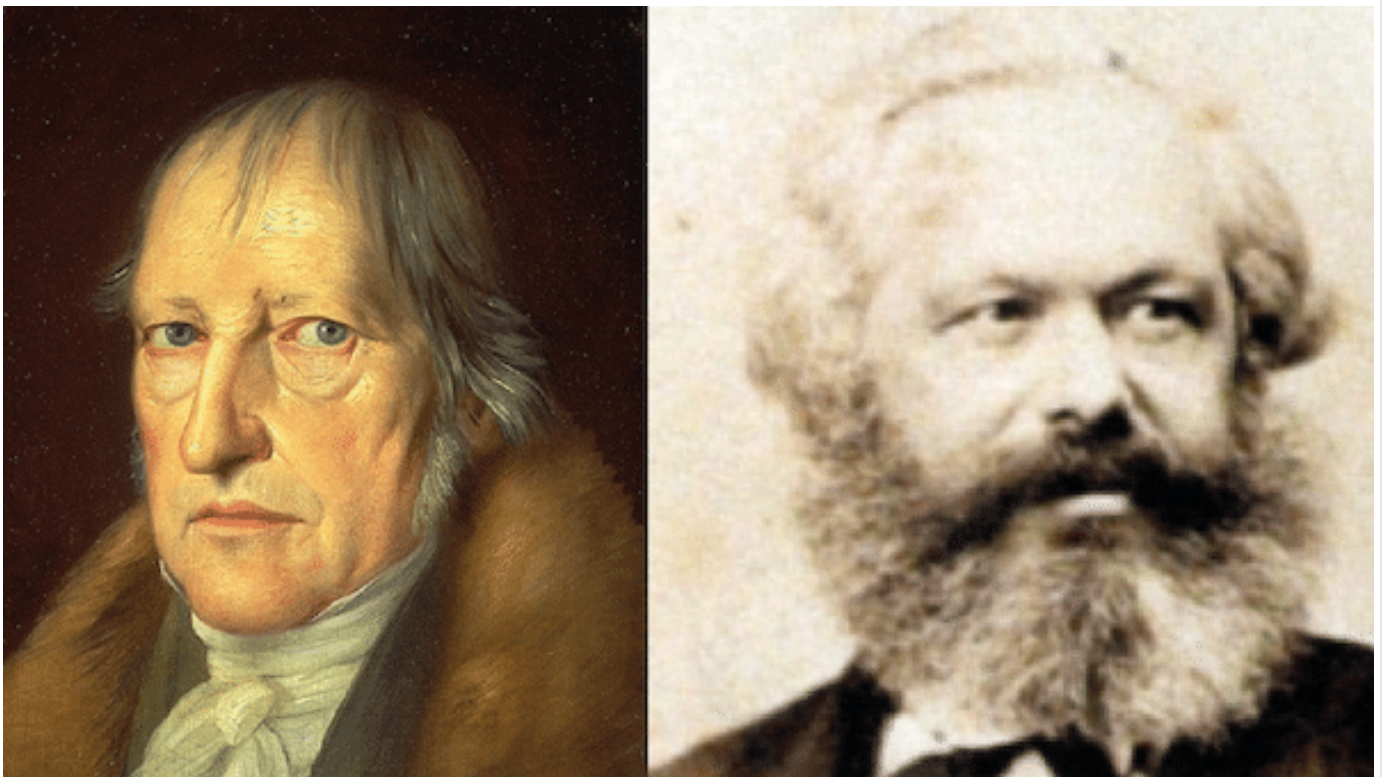

Marxist revolutionaries strive to analyze the surrounding bourgeois, capitalist world with the goal of fundamentally changing it. But the hegemony of bourgeois metaphysical modes of thinking in capitalist societies–modes that always end up assuring us that the essential institutions of bourgeois society are not susceptible to change and are as permanent as the law of gravity–can sometimes derail this goal. Karl Marx (1818-83), like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) before him, emphasized that human societies can and do undergo dramatic transformations, moving from one social order to another where each formation is governed by its own distinct laws, and a discontinuous logic separates one social order from the next. In other words, both their philosophies exhibit an appreciation for a historical perspective almost totally lacking in preceding philosophical systems. Accordingly, both Marx and Hegel found the dominant scientific method of their time, the method of physics with its static laws, to be inadequate for capturing the logic of social transformations. Hegel was the first to turn to the dialectical method, whose origins go back at least to Plato, and used it to capture the logic of these historical leaps while at the same time systematically developing the logic of the dialectic itself. Marx, who was heavily influenced by Hegel, adopted his dialectic, but, as we will see, gave it a critical turn, declaring in the 1873 Afterward to the second German edition of Capital, Volume I: “My dialectical method is not only different from the Hegelian, but its direct opposite.” Nevertheless, their respective dialectical methods share fundamental features in common. In the same Afterward Marx credited Hegel with being “the first to present its general form of working in a comprehensive and conscious manner.” This essay will begin with an explication of these “general forms,” particularly when applied to understanding humanity; then show how they were employed by Marx in his revolutionary analysis of bourgeois society; and conclude by offering examples of both dialectical and metaphysical modes of thinking as applied to current social practices. As we shall see below, metaphysical thinking presently dominates both everyday thought and bourgeois philosophical modes of analysis. Dialectical thought, while not rejecting metaphysical thinking altogether, attempts to supersede it. While the dialectic is a powerful weapon that can help us escape from the shackles of bourgeois thinking, it does not offer an unambiguous tool that will produce the same results no matter who employs it. It is not a mechanical instrument. Nevertheless, it does provide some useful guidelines for revolutionary socialists who seek to understand our surrounding world for the purpose of changing it. Preliminaries: The philosophical context Understanding Hegel’s dialectical method requires an acquaintance with the method it was constructed to supersede–the prevailing natural scientific method that dominated the philosophical/scientific scene of Hegel’s time–particularly the method of physics, a form of thought that Hegel designated as “metaphysical.” Initiated in the 15th —16th centuries in Europe in conjunction with the rise of capitalism, this natural scientific method conceived nature as composed of discrete elements that could be understood in isolation from one another and that interacted in predictable ways according to inflexible laws such as cause and effect. As Friedrich Engels observed in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific: “To the metaphysician, things and their mental reflexes, ideas, are isolated, are to be considered one after the other and apart from each other, are objects of investigation fixed, rigid, given once for all.” The goal of the scientist was to discover the laws governing the interaction of these objects (for example, the law of gravity) and logically deduce predictions based on these laws, which then allowed humanity to advance its control over nature and more successfully satisfy human material needs. The natural sciences made huge gains during this period in discovering the laws of nature, thanks to Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), Isaac Newton (1643-1727), and many others. Impressed by the positive impact of the natural sciences on humanity, philosophers quickly borrowed its method and applied it to humans with the hope of organizing society along “scientific” lines. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) justified this transition by arguing that human beings, after all, were no more than complicated mechanisms, where “the heart [is] but a spring; and the nerves but so many strings; and the joints but so many wheels” (The Leviathan, Introduction). He added society was nothing more than an artificial man and hence could be captured by the same method as nature. Hobbes proceeded to argue that people are by nature competitive, distrustful of one another, and desiring of glory and hence engage in acts that are entirely predictable. For example, they will be aggressive with one another unless restrained by the threat of force. Using these assumptions about the nature of the individual, Hobbes proceeded to deduce the appropriate governmental structure for society. Philosophers of this period, then, assumed that people had a fixed nature in the same way as natural objects. That is, just as water has certain permanent characteristics that allow us to predict its behavior, and the falling of an object to the ground is completely predictable if the relevant variables are known and animal species have their fixed nature, human nature is equally fixed and predictable. Many agreed with Hobbes about the essential qualities of this nature: people are selfish, competitive and self-serving. Perhaps most importantly because of its methodological implications, they believed humans were essentially individualistic, meaning that each individual was assumed to possess a full range of human characteristics apart from their relation to other human individuals. Human societies were simply the sum of these atomic units and nothing more. Hegel’s revolutionary approach to the question of human reality required that he adopt a revolutionary method to capture its logic–the dialectic. His dialectical method, therefore, cannot be separated from the content of his social theory: “… this dialectic is not an activity of subjective thinking applied to some matter externally, but it is rather the matter’s very soul putting forth its branches and fruit organically.” (Philosophy of Religion) Here are some of the defining features of that social theory: First, societies are living organisms, which means they are composed of members that derive their identity from their place in the organism. Each member reciprocally interacts with other members as well as with their encompassing society, but society has a far greater influence on the individual than vice versa. In a significant sense, individuals are not even human apart from this social context, which provides them with language, a style of thinking, customs, a religion, morality, etc. As Hegel observed, “The individual is the offspring of his people, of his world …; he may spread himself out as he will, he cannot escape out of his time any more than out of his skin ….” (History of Philosophy). Anthropologists have made a similar observation. In a 1947 document addressed to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, the American Anthropological Association, in arguing that human rights should not be confined to individual rights but extended to community rights, emphasized that individual identity is inextricably tied to the surrounding community: "If we begin as we must, with the individual, we find that from the moment of his birth not only his behavior, but his very thought, his hopes, aspirations, the moral values which direct his action and justify and give meaning to his life in his own eyes and those of his fellows, are shaped by the body of custom of the group of which he becomes a member… [T]he personality of the individual can develop only in terms of the culture of his society." In other words, Hegel offers a radical rejection of the prevailing philosophical assumptions of his time that individuals are atomistic and autonomous, that they have a fully developed personality apart from their social relations, that societies are nothing more than the sum of these individuals, and that it makes sense to view the origin of societies as resulting from individuals engaging in contracts with one another where they agree to respect certain basic rules, etc. Second, since all natural organisms undergo a process of development to maturity–the acorn, for example, develops into an oak tree and children become adults–Hegel claimed humanity itself has matured through the ages. Just as the acorn has embedded in it its destiny to become an oak tree, humanity, which initially is governed more by instincts and feelings, is driven to become rational, free and self-conscious, a goal that guides the entire process: “We have defined the goal of history as consisting in the [human] spirit’s development towards self-consciousness,” (Philosophy of World History) a goal Hegel equated with fully developed freedom and rationality: “… for freedom by definition, is self-knowledge” (Philosophy of World History). This end-goal guides the entire (teleological) process: “Just as in the living organism generally, everything is already contained, in an ideal manner, in the germ and is brought forth by the germ itself, not by an alien power, so too must all the particular forms of living mind grow out of its Notion as from their germ” (The Philosophy of Mind). In other words, in the early stages, humanity was more instinctual than rational but gradually rationality became the more powerful drive: “World history begins with its universal end … it is as yet only an inward, basic unconscious impulse, and the whole activity of world history … is a constant endeavor to make the impulse conscious.” (Philosophy of World History) So, for Hegel, human history follows a logical path, or as he puts it, “… reason governs the world, and … world history is therefore a rational process.” (Philosophy of World History) Third, and following from the previous point, each stage of history has its own unique logic that permeates all its institutions. According to Hegel, The forms of thought or the points of view and principles which hold good in the sciences and constitute the ultimate support of all their matter, are not peculiar to them, but are common to the condition and culture of the time and of the people… All its knowledge and ideas are permeated and governed by a metaphysic such as this; it is the net in which all the concrete matter which occupies mankind in action and in impulses, is grasped (History of Philosophy). Accordingly, Hegel rejects the notion of a fixed human nature but argues that humans exhibit different qualities during different stages of history. This changing human nature distinguishes humans from other animal species, which lack consciousness and the ability to reflect on themselves and fundamentally change their behavior. Fourth, the transition from one historical stage to the next results from contradictions that emerge in the earlier stage, as will be explained below. Hegel’s dialectical exposition of practical freedom For Hegel, the free will or the completely self-determined will goes to the heart of what it means to be a human being. But we are not born with this capacity in a fully developed state. Rather, a modern individual must mature into adulthood to be able to exercise freedom in its most advanced form, and humanity has required millennia to acquire the proper social institutions that allow human freedom to attain its full potential. Hegel believed that, through the ages, humans have practiced three basic forms of freedom; each subsequent form, having been built on its predecessor, is more sophisticated and liberating. He did not consider these stages as completely distinct: the lower forms of freedom do not entirely disappear but are incorporated into the higher forms so that the highest form is a rich synthesis of all three. Personal freedom for Hegel represents the most elementary form. The individual “freely” chooses which impulses (desires/interests) to pursue, without this choice being determined by the impulse. Hegel describes personal freedom, which constitutes the first step in his dialectical presentation, as “abstract immediacy” or “the undifferentiated stage,” meaning we do not thoughtfully reflect on our options but arbitrarily decide without thinking which to pursue. Bourgeois theorists in modern capitalist societies, perhaps because they are surrounded by an economy that sets a premium on self-interest and greed, typically assume personal freedom is the only kind of freedom and go no further. Hobbes, for example, defined freedom as, “In deliberation, the last appetite or aversion immediately adhering to the action, or to the omission thereof, is that we call the will” (The Leviathan, Part I, Chapter 6). In other words, the will is all about desires and feelings, not about thoughtful choices. The second step of the dialectic is “particularity” or “difference” and amounts to looking at the real world to find the particular ways in which personal freedom, which initially was merely a vague undifferentiated universal, is realized. Hegel points to the institution of private property where individuals are granted the exclusive right over designated material objects as the purest manifestation of personal freedom since individuals can pursue their passions without fear of interference by others. However, this dominion over property, to operate successfully, requires laws to protect the rights of property owners, including laws governing the exchange of property by means of contracts as well as an agency mandated to enforce these laws. Without this legal apparatus, the will of the individual would not be free because of constant threats by other members of society who attempt to monopolize these material objects for their own pleasure. Consequently, this first conception of human freedom, which appeared to be a simple and unambiguous relation between a person and an object, requires a network of social relations–laws and a police force–to operate successfully. But then a contradiction arises: while individuals might enjoy the protection of their own property by state laws, those same laws, when used to protect the property rights of their neighbors, can feel like external coercion, especially if they covet their neighbor’s property. Hence, personal freedom does not fulfill the promise of a fully self-determined will–a will free of external constraints. It encounters its “negation” because of the constraining force of society’s laws. Hegel emphasized the human mind seeks unity and cohesion: “But the spirit cannot remain in a state of opposition. It seeks unification, and in this unification lies the higher principle” (Philosophy of World History). Accordingly, when contradictions flow from a position, the impulse is to seek their resolution by forging a new, hopefully contradiction-free conception. This represents the third step of the dialectic–a mediated unity or the negation of the negation, meaning that a new unifying framework or totality emerges that manages to retain the past conception of a free will but resolves the contradictions by situating them in a more comprehensive, nuanced unity, which amounts to a paradigm (world view) shift or a qualitative transformation rather than simply a quantitative addition. We have a simple illustration of Hegel’s reasoning when we consider a person who measures 5 feet tall, then later measures 5 feet and 5 inches, an apparent contradiction. Of course, the contradiction can be resolved by bringing into consideration that the individual is growing; a temporal dimension is added to the picture, which was previously present only implicitly, and in this way the contradiction is resolved in a larger, more comprehensive totality. Returning to Hegel’s analysis of freedom, moral freedom for Hegel represents this advance over personal freedom: it retains the idea of the pursuit of desires and the necessity of law and a system of justice required for this pursuit. But the law is no longer conceived as being imposed externally but as constructed entirely by the individual through a process of thoughtful reflection without borrowing assumptions from society. Immanuel Kant’s (1724-1804) moral law that we should always treat other people as an end and never as a means is an example. Since individuals themselves construct these laws based on their own sense of morality, the laws are not experienced as an external constraint but as a liberating guide to action, allowing for the pursuit of some impulses while rejecting others, depending on whether they conform to or violate the law. We have a new totality, then, in the sense that a new conception of free will and the individual emerges–an individual who has desires and impulses but also has the faculty of reason that generates moral laws which serve as a guide to acting on these desires and impulses. With this transition to moral freedom human nature shifts from being less impulsive to being more thoughtful and therefore, according to Hegel, freer. The first step of Hegel’s dialectic was the abstract universal. The second step is constituted by particulars or differences or contradictions. Hegel calls the third dialectical step “mediated unity” or a new “totality,” as was exemplified in the concept of moral freedom. It represents a new paradigm where the pursuit of desires remains but is now mediated by a moral law–a law that is no longer external to the individual but incorporated into the individual’s will with the result that the will is thoughtful, not impulsive or arbitrary. While representing the conclusion of the first of the three-step dialectical progression, moral freedom in turn becomes the first step–the immediate, the abstract, formal universal–in relation to a new dialectical progression. Once again, we look to see the particular forms moral freedom assumes when put into practice. And once again we find that moral freedom succumbs to contradictions. First, it cannot be realized by isolated individuals apart from their social relations but requires that individuals be socialized and educated to think rationally about possible principles of action. On the most basic level, the individual requires language, a capacity that cannot be acquired without socialization. Second, these moral principles generated by the isolated individual are, according to Hegel, too abstract, formal, and empty to serve as reliable guides in navigating life’s choices. For example, Kant offered a second version of his moral law: ask if it would be consistent to will that everyone do what you are proposing to do. Stealing property from someone else would not pass such a test because thieves do not want others to steal from them. But a problem arises here. In the Phenomenology of Spirit, for example, Hegel raises the question, “Ought it be an absolute law that there should be property?” In other words, is the institution of private property an unqualified good or does it harbor contradictions such as in the case of stealing? Would it fail to pass one of Kant’s moral laws? If contradictions arise, then the proposal fails. The answer Hegel supplies is that neither private property nor its opposite, “to each according to his need,” is self-contradictory, and therefore abstract, empty, formal laws alone are insufficient to serve as a guide. Contradictions only arise if we presuppose the existence of some social practice such as private property. Then stealing represents a contradiction of it. Unless one borrows concrete values and practices from the surrounding society, everything passes these highly abstract moral-law tests. But moral freedom purported to provide a law that was centered exclusively in the isolated individual–hence, a contradiction. Both these problems point to the fact that moral freedom alone cannot provide a coherent account of a fully self-determined will but must be supplemented with the indispensable role of social institutions, whether in the form of education or institutions such as private property, which leads to the third and highest form of practical freedom. Social or ethical freedom, while incorporating elements from both personal and moral freedom, represents a culminating advance by avoiding the contradictions that encumbered its predecessors. Taking into consideration the lessons that emerged from both personal and moral freedom, namely that freedom cannot be fully realized by an isolated individual, Hegel argues in favor of a more social and encompassing version of free will. Social freedom envisions individuals coming together to construct–through rational discussion–the kind of social and political institutions that embody a rational logic or universal justice. Here, people collectively take control of their world, either directly or through their representatives, and mold it to their will by creating institutions that safeguard personal and moral freedom. Personal freedom is preserved through the institution of private property. Moral freedom, while supplemented by the surrounding culture, persists in the sense that individuals may critically evaluate their surrounding social institutions. In this way the individual is still allowed to exercise their unique individuality but now exercises it within a rational social framework. Social freedom represents a revolutionary advance in several respects. First, the philosophical assumption that individuals are primordial and societies are secondary and inessential, which dominated the thought of Hegel’s contemporaries, is replaced by a philosophy built on the premise that human beings, while containing an element of individuality, are essentially social and cannot reach their full human potential apart from their membership in society. In The Philosophy of Mind, for example, Hegel argues: “Only in such a manner is true freedom realized; for since this consists in my identity with the other, I am only truly free when the other is also free and is recognized by me as free. This freedom of one in the other unites men in an inward manner, whereas needs and necessity bring them together only externally.” Second, by abandoning the supremacy of the isolated individual and replacing it with a collective subject, the world seems to undergo a transformation: from the standpoint of the isolated individual, the social world appears immutable but becomes pliant when confronted by large numbers of people who act collectively with a conscious plan. Third, human freedom in its fullest sense is not a matter of acting impulsively or thoughtlessly indulging in desires but acting rationally. Fourth, what counts as rational action is not determined by the isolated individual but by people in communication with one another and results from an open discussion. As Hegel said, “What is to be authoritative nowadays derives its authority, not at all from force, only to a small extent from habit and custom, really from insight and argument.” (Philosophy of Religion) Fifth, individuals act collectively not merely to create social institutions that will serve to safeguard personal and moral freedom. If this were the case, then individual freedom would remain supreme. Rather, social freedom also becomes an end in-itself. Individuals realizing their identity, in addition to having an individual side, is essentially tied to their surrounding community, its culture and social practices. We understand that we are not autonomous, fully defined humans apart from society but that we are more like members of a living organism. People feel that they are truly themselves when they are actively engaged with other members of the community, formulating policies where all are equally respected and each has the opportunity to influence the opinion of others. In this way individuals can experience a deep satisfaction by exercising their full social humanity. A summary of Hegel’s dialectic Hegel employs multiple ways to describe the dialectical process, but they are all pointing to the same general features. We have already touched on his description of the dialectic as starting with “abstract immediacy” or the “undifferentiated” stage. He also refers to this first step as “the abstract universal” or an “unconscious impulse.” The second step involves the “particular” (or “difference”), meaning the ways in which the first step plays out in existence. The third step unites the first two steps in a “mediated unity.” But Hegel also describes this process more abstractly as moving from the universal, to the particular, and then to the individual. In other words, we start with a vague idea or impulse, look at the particular ways it appears in the world, and then formulate a new more differentiated universal that resolves the contradictions appearing in the second step by situating them in a more encompassing, more complex universal. This third step then serves as the starting point for a new dialectical progression until the final point is reached. Hegel also describes the second step as the negation of the first step since the second step reveals contradictions, while the third step, which resolves the contradictions in a larger totality, is the negation of the negation. But Hegel uses another important formulation where something transitions from being “in-itself” to being “for-itself.” The in-itself is implicit, meaning that we are not aware of it, while the for-itself is where the implicit has become explicit and we have become conscious of it. For example, in our investigation of moral freedom we started with the moral actor as an isolated individual. But upon reflection we come to understand that the ability of an individual to act morally presupposes being socialized to think rationally and requires established social practices to serve as a context within which to employ moral principles. We become conscious of this necessary social context by reflecting on the practice of moral freedom; if we do not reflect, we do not become aware of it and, accordingly, cannot proceed thoughtfully. For Hegel, then, the process of history amounts to becoming increasingly self-conscious of what we are unconsciously presupposing so that we choose a course of action, not because we are impelled by unconscious impulses, but because we consciously conclude it represents the most reasonable alternative. He adds in Philosophy of World History, as was mentioned before: “… freedom, by definition, is self-consciousness,” and later adds, “We have defined this goal of history as consisting in the [human] spirit’s development towards self-consciousness, or in it making this world conform to itself (for the two are identical).” In other words, by engaging in collective action according to a plan that has been consciously adopted based on “insight and argument” rather than individuals pursuing their own selfish ends, we can create rational institutions that conform to our ideas of what is right. For example, Hegel argues in The Philosophy of Mind: Man is implicitly rational; herein lies the possibility of equal justice for all men and the futility of a rigid distinction between races which have rights and those which have none. Marx’s use of the dialectic Marx’s social philosophy shares many fundamental points with Hegel’s. Otherwise, the dialectic would be irrelevant. First, Marx also regards society as an organism, meaning that the isolated individual apart from society is no longer considered a meaningful construct. Rather, individuals are subordinate and to a large degree defined by their surrounding society. Individuals producing in society–hence socially determined individual production–is, of course, the point of departure. The individual and isolated hunter and fisherman, with whom Smith and Ricardo begin, belongs among the unimaginative conceits of the eighteenth-century Robinsonades…. (Introduction to the Grundrisse) [“Robinsonades” refers to Daniel Dafoe’s fictional character, Robinson Crusoe and the conception of humans as self-made individuals.] Only in a community [with others has each] individual the means of cultivating his gifts in all directions; only in the community, therefore, is personal freedom possible. (The German Ideology) Second, both see history as progressing in the direction of humanity becoming progressively free, rational, and self-conscious. Marx says, for example: “Reason nevertheless prevails in world history” (Comments on the North American Events, Die Presse, October 12, 1862). For Marx, as humanity gains more control over its material environment through technological advances, the potential for taking control of social relations and exercising social freedom by collectively directing the economy according to a rational plan, as opposed to letting the blind forces of the market dictate economic decisions, becomes increasingly possible. The overthrow of capitalism and move towards communism makes this imminently possible: “Let us finally imagine, for a change, an association of free men, working with the means of production held in common, and expending their many different forms of labor power in full self-consciousness as one single social force.” (Capital, Vol. 1, Chapter 1) And: With the community of revolutionary proletarians, on the other hand, who take their conditions of existence and those of all members of society under their control, it is just the reverse; it is as individuals that the individuals participate in it. It is just this combination of individuals [assuming the advanced stage of modern productive forces] which puts the conditions of the free development and movement of individuals under their control…. (The German Ideology) Third, Marx also viewed history as composed of distinct stages, but diverges from Hegel in their identification because of his materialist/economic approach to history. Accordingly, the categories he identifies are first communal societies, followed by the slave societies of Greece and Rome, then feudalism, then capitalism, to be followed sometime in the future by communism. Like Hegel, Marx argued each stage contains its own distinct logic: “The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life” (Preface to Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy). This means that the nature of the family, education, culture in general, philosophy, the state and politics, not to mention human nature, are all organically connected to the economic infrastructure at any particular historical stage. Fourth, the emergence of fundamental contradictions within society is responsible for its revolutionary transformation. For Marx, these contradictions are above all generated in the economy with the development of classes divided by antagonistic and contradictory interests, leading to the downfall of one society after another while giving birth to new, higher forms: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” (Manifesto of the Communist Party) As a result of these points of commonality, Marx adopts Hegel’s dialectic with the same schema of abstract, undifferentiated universal, followed by its negation in the form of particular determinations, and then to their resolution in a new mediated, more encompassing universal, or the negation of the negation. Marx’s 1857 Introduction to the Grundrisse contains the most extended discussion of his method: The economists of the seventeenth century, e.g., always begin with the living whole, with population, nation, state, several states, etc.; but they always conclude by discovering through analysis a small number of determinant, abstract, general relations such as division of labor, money, value, etc. As soon as these individual moments had been more or less firmly established and abstracted, there began the economic systems, which ascended from the simple relations, such as labor, division of labor, need, exchange value, to the level of the state, exchange between nations and the world market. The latter is obviously the scientifically correct method. The concrete is concrete because it is the concentration of many determinations, hence unity of the diverse. Here Marx is describing the dialectic that starts with the abstract universal (population, etc.), then moves to particular determinations (the division of labor, money, etc.), and concludes by reconstructing a new universal that contains these determinations in the form of a mediated unity. Marx’s monumental work, Capital, is an attempt to take the abstract notion of a pre-capitalist economy and show that, when it plays out in reality and develops into capitalism, the first stage of equality where everyone is an owner and performs their own labor is soon “negated” and replaced by a society composed of two opposed, unequal classes where a minority enjoys huge wealth while the majority struggles to survive. In other words, capitalism is preceded by “individual private property” or what has been referred to as “simple commodity production” or “simple exchange” (the abstract universal). In this stage individuals own their tools, etc., they perform labor and then own the product of their labor which they can take to the market for purposes of exchange–a system that at the outset lacks class divisions, equality prevails, and exploitation is absent. But capitalism negates this stage: as it develops, some of these producers go bankrupt (perhaps demand is lacking for their product, or perhaps they were wiped out by bad weather) and must seek employment from others to survive, which amounts to the first step towards capitalism proper where some in society (the capitalist class) own the means of production while others (the working class) own only their ability to work and must seek employment from those with the means of production. But capitalists have a competitive advantage over individual producers because of their size and efficiency, which results in more and more individual producers being thrown into the working class. Inevitably, wealth becomes concentrated in the hands of a minority of capitalists while the vast majority of the population is converted into workers employed by them. These classes are the particular determinations that flow from the original starting point of simple commodity production. Marx describes this movement in this way: “The capitalist mode of appropriation, the result of the capitalist mode of production, produces capitalist private property. This is the first negation of individual private property, as founded on the labor of the proprietor.” (Capital, Volume I, Chapter 32) But when society is divided into two vastly unequal classes with opposed interests, where the working class represents the vast majority of the population but is increasingly exploited, workers come to the realization that they are not simply autonomous individuals but members of a class defined by class exploitation. Instead of being unaware of their class membership, they become class-conscious. Their class membership, which was unconscious and “in-itself” becomes conscious and “for-itself.” Workers realize their misery is not the result of their own individual failure but of their class membership and can then engage in class struggle to liberate themselves as a class by abolishing the capitalist class system and replacing it with communism. This represents the negation of the negation: “But capitalist production begets, with the inexorability of a law of Nature, its own negation. It [the system that replaces capitalism] is the negation of negation. This does not re-establish private property for the producer but gives him individual property based on the acquisitions of the capitalist era: i.e., on co-operation and the possession in common of the land and of the means of production.” (Capital, Volume I, Chapter 32) In The Critique of the Gotha Program (1875), Marx argued that capitalist society could not immediately be replaced by a full-blown communist society but rather its revolutionary transformation would proceed dialectically: capitalism, with its deep division into antagonistic classes, would be replaced by its negation where classes would be abolished by adopting a new system of wealth distribution where people would be rewarded according to the amount of labor they performed, meaning that capitalists, too, would need to work to get an income. But Marx was quick to point out in this essay that this stage of the revolution had its problems because of contradictory results: The right of the producers is proportional to the labor they supply; the equality consists in the fact that measurement is made with an equal standard, labor. But one man is superior to another physically, or mentally, and supplies more labor in the same time, or can labor for a longer time; and labor, to serve as a measure, must be defined by its duration or intensity, otherwise it ceases to be a standard of measurement. This equal right is an unequal right for unequal labor. It recognizes no class differences, because everyone is only a worker like everyone else; but it tacitly recognizes unequal individual endowment, and thus productive capacity, as a natural privilege. It is, therefore, a right of inequality, in its content, like every right. With the appearance of this contradiction, eventually a new principle of distribution would be introduced, representing the negation of the negation: In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but life’s prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly–only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs! (The Critique of the Gotha Program) In other words, people will no longer be treated with an abstract universal law of distribution blind to divergent individual needs but distribution will be conducted in an organic way so the different needs of individuals will be factored into the distribution of wealth. Of course, such a principle cannot be immediately adopted after the overthrow of capitalism because human nature will still be stamped with the effects of capitalism, where self-interest and an abstract, individualistic sense of entitlement prevail. Once this mindset is slowly eradicated by new social relations that engender a sense of solidarity, distribution can be established on a more personal, humanitarian, organic basis. A quick review of the dialectic The first contact we have with the surrounding world occurs with our senses–sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell–that provide us with a series of sense experiences with little connection among them. Gradually we begin to forge these connections and our world appears more continuous and rational. We organize our experiences according to their relation in time and space, by placing similar experiences under the same category and then connect these categories by means of relations such as cause and effect, substance and accidents, etc. Everyday thinking or what passes for common sense operates on this metaphysical level with its rigid categories. We see our surrounding world as static. One tree, for example, might die and be replaced by another, but the category “tree” remains. The law of gravity never changes. In a similar way we assume the surrounding society is immutable. Those who advocate radical change are dismissed as unrealistic. This apparently static universe is tied to the assumption that thought on the one hand is entirely divorced from the world of existence on the other. Universal categories such as tree, animal, private property, and wage labor are seen as purely mental constructs, while existence is composed of purely material objects or practices. The possibility of changing our material/social world to conform to our ideas so that ideas become a part of reality is beyond consideration. However, once we turn our attention to humanity’s long history and note that human societies during different epochs have displayed vastly different forms, each with their own distinct economy, political system, philosophy, human nature, etc., then the question arises: is there a logical connection between these social formations so that history itself is rational, or is history governed by pure chance? Hegel’s dialectic was an attempt to affirm the former alternative. Accordingly, it takes us beyond the level of the fixed categories into the realm of an organic system that undergoes development with an underlying logic connecting one stage to the next, illuminating the long journey of humanity to self-knowledge, rationality and freedom–with the understanding, of course, that many regressions along the way can stall progress. Both Marx and Hegel come to the realization that all past societies have been our [humanity’s] own creation, although without conscious planning, and each subsequent social formation represents an advance over its predecessor since it represents a gain in self-knowledge or technical control over nature, culminating in the realization that we can consciously make history according to a collective plan. While rigid metaphysical thinking dominates common sense, nevertheless some individuals, perhaps without any special training, intuitively recognize the need to go further and take into consideration the social/historical context to better understand human reality. They may also be open to the possibility of radical social upheaval and revolutionary change. To this extent, they are taking a step in the direction of dialectical thinking, an impulse that can be greatly enhanced by an introductory acquaintance with its forms. Examples of dialectical and metaphysical modes of thinking 1. The metaphysical practice of assigning grades to student work When children enter school, capitalist culture deems it appropriate to motivate their behavior by assigning grades to their work depending on its quality, emphasizing to the student how important grades are for their entire future. The grade is supposed to represent an accurate reflection of the student’s performance and/or abilities. But this claim is fraught with contradictions. For example, teachers cannot appeal to a single, unambiguous, universal standard of measurement when assigning grades. Are students being measured according to how much improvement they make during the school term so that they are not penalized if they enter the class less prepared than other students? Or are they graded on how their performance compares to that of the other students, in which case their grade can fluctuate according to who is in the class? Is it possible that all the students in a class do outstanding work and all deserve an ‘A’? Instead of assuming today’s grades are inflated, might the grading policies of the past have been deflated? The teacher’s performance also plays a role in a student’s grade. If the teacher does a poor job explaining the material to the students, or the test questions are confusing or unrelated to the material covered in class, the student’s grade can be adversely affected. Or the teacher might simply grade unfairly where they give generous grades to students they like. It is hard to say what will replace grades, if anything, in a socialist society, but surely grades as we know them will be abolished. 2. Casting moral blame as a metaphysical exercise Capitalist society, with its hyper individualism, creates a culture in which individuals cast moral judgments on one another purely as individuals, stripped of any social or historical context, with the assumption that the individual is entirely responsible for who they are and what they do. People who live in poverty are themselves to blame, as if poverty results above all from a failure of individual will-power rather than social policies designed to ensure part of the population remains poor. This tendency is particularly egregious in a situation where one nation has colonized a second nation or people. When an occupation drags on for decades, as in Gaza and the West Bank, and the oppressed population is treated with daily violence and cruelty; where Israel arrests Palestinians in the occupied territories without charging them with crimes; humiliates them in public by making Palestinians remove their clothes and dance; keeps them imprisoned indefinitely or tries them in rigged military courts; or incarcerates those in Gaza in an open-air prison where only enough food is allowed in to keep the population barely above starvation; when medical supplies allowed to enter are insufficient; where Palestinians are routinely and illegally pushed out of their houses and off their land with impunity or murdered with impunity; when the oppressed population lashes out in violent desperation after exhausting non-violent alternatives, moral condemnation suddenly rises to the occasion: those who have lived comparatively privileged lives are quick to condemn the Palestinian people for resorting to indiscriminate violence, thereby stripping the victims of their humanity by stripping them of their social/historical context. 3. Metaphysical politics US foreign policy, instead of viewing other societies, for example, Iraq or Afghanistan, as rich, complex, organic unities of culture, religion, economic practices, and system of government, assumes that by merely changing the government they can transform the country into a liberal western democracy, blind to the fact that the government does not exist in isolation but has deep connections to the surrounding economy and culture. Accordingly, U.S. foreign policy adventures typically end in abysmal failures. Even on the left many assume that working-class power can be achieved by electing socialists to office who will then, presumably, transform the nation from capitalism to socialism. However, electing politicians to office in capitalist societies does not require collective action on the part of the working class. The election process reflects the capitalist culture of operating as isolated individuals: everyone casts their ballot privately. The individualistic culture of capitalism remains intact. The Bernie Sanders’ “movement,” which was so highly acclaimed by many on the left, remained within the framework of capitalist individualism with its top-down decision-making where Sanders alone dictated policy, and everyone one else could either sign on or stay out. People participated as individuals, and nothing in the Sanders’ campaign remotely challenged that dynamic. His supporters were not afforded the opportunity to come together, discuss policy, and vote on how to proceed, a process that would have forged bonds among participants. Unsurprisingly, the “movement” collapsed the day after Sanders lost the election. Capitalism cannot be transformed into socialism without challenging the culture of the isolated individual. Moreover, revolutionary change cannot be achieved by a political elite at the top through piecemeal reforms as the German Social Democrat Eduard Bernstein (1850-1932) once proposed and many today consider possible. First, such an approach fails to take into consideration the counterattack the capitalist class will launch the moment these reforms become threatening. It fails to take into consideration that capitalist democracy tilts decisively in favor of the capitalists, especially with money that can be used to remove undesirable politicians. Second, progressive politicians who are elected to office join a political elite who have thoroughly adapted to the pervasive, corrupt capitalist culture that can quickly drown newcomers in a sea of self-interest and greed where money and power reign supreme. Third, and perhaps most importantly, capitalist culture is again not challenged because for the most part the working class remains passive and disengaged. 4. A dialectical approach to the union movement The recently unionized Amazon workers were confronted with a contradiction. Some argued the workers should organize a strike to pressure Amazon into negotiating a contract with favorable provisions. But others argued that the workers could not afford to strike, that they were living paycheck to paycheck and could not stay out long enough to win. Both sides had valid points. Here, a dialectical resolution could have been forged by bringing the larger union movement that is currently on the rise into the picture. An appeal could have been made to these other unions–many have large financial reserves–to contribute to a strike fund to support the Amazon workers long enough to prevail. The contradiction is resolved by enlarging the focus and situating the Amazon union in the totality of the union movement. 5. A dialectical political strategy For these reasons, Marx and Engels insisted that the overthrow of capitalism and introduction of socialism must be accomplished by the working class itself, defying the prevailing capitalist assumption that workers lack the insight and initiative. In an 1879 letter Engels explained: “At the founding of the International we expressly formulated the battle cry: The emancipation of the working class must be achieved by the working class itself.” (Marx-Engels Correspondence, September 17-18, 1879) When workers escape their passivity and act collectively to liberate themselves, they take the first step in building a new culture: workers in large numbers abandon their inter-competition and individual isolation; they organize themselves, a skill they have already acquired from their union experience; they discuss among themselves possible strategies in going forward, listening to one another and adjusting their positions when convinced of a better alternative, all while strengthening their social bonds. Then, by adopting policies that have the support of the majority, the individual perspective of each member is respected but the will of the majority prevails, enabling them to act collectively. The relations among workers undergo a dialectical transformation: instead of operating as isolated individuals, they transform themselves into members of an organic totality prepared to collectively change the world. This means, then, the capitalist state cannot remain intact after a working-class revolution since it has been constructed specifically to serve the interests of the capitalist class by requiring that workers participate as isolated individuals, not as members of an association. For this reason, Marx insisted that in the move to socialism, the capitalist state must be “smashed” and replaced by a workers’ state, where members of the working class do not participate as isolated individuals but as members of a community. In the 1871 Paris Commune, for example, workers participated through their neighborhood communes where they would discuss policies and direct their representatives how to vote. Similarly, in the early days of the Soviet Union workers, soldiers and peasants participated through their respective soviets. They would meet, debate policies, vote and direct their elected representatives to implement their decisions. A December 2019 New York Times article, “When Does Activism Become Powerful?” by Hahrie Han (Johns Hopkins University), reported that empirical studies confirm activism becomes powerful when “leaders built organizations designed to strengthen relationships with and among members”, and “that people were the source of their power.” The article continued: “These organizations put people in settings where they would build connections with one another, learn to work together and negotiate about the things they wanted, even with people who were different from them.” In contrast, “three million people marching down a boulevard may not bring about change”—precisely because they do not establish relations among one another and remain atomized. During the process of working-class activation, human nature undergoes a change. Capitalism’s hyper individualism is rejected and instead we have what Hegel described in the Phenomenology of Spirit as the “’I’ that is ‘We’ and ‘We’ that is ‘I’.” Workers embrace humanistic social relations where together they support one another, gain a sense of camaraderie, and take control of their lives by adopting new policies that champion a better world. The union slogan, “An injury to one is an injury to all,” is taken to heart, and “In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” (Manifesto of the Communist Party, Chapter 2). When workers begin to create this working-class culture, and when they score big wins over their employers through massive strikes, etc., the movement can spread quickly. Others in the working class are then inspired by their courage, their values and their victories and want to become a part of this historic uprising. Hence, a new logic begins to rapidly spread that can lead to a revolutionary upheaval where working people take charge of society and proceed to transform it according to their own definitions of democracy, justice and freedom. Conclusion Metaphysical thinking can undermine this undertaking. Unable to imagine sudden, unexpected, upheavals where the logic of one historical stage is replaced by a new logic, it leads to the reinforcement of capitalist institutions, encourages reformism, and sidelines the working class. But these profound transformations can take place when large numbers of workers decide to put up a fight, as happened in the 1930s, and could happen again at any time. While not overthrowing capitalism, the uprisings of the 1930s changed its nature for decades to come. It is time for today’s working class to finish the job their predecessors began. The dialectic is waiting to serve them. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I am particularly grateful to Bill Leumer for his helpful suggestions and to Frederick Neuhouser for his extraordinarily lucid books and articles on Hegel with thoughtful step-by-step elucidations of some of Hegel’s most abstruse ideas, making them accessible in ways that few others have done. AuthorAnn Robertson is a Lecturer Faculty emeritus of the Philosophy Department at San Francisco State University and a member of the California Faculty Association. This article was produced by Monthly Review. Archives February 2024

0 Comments