|

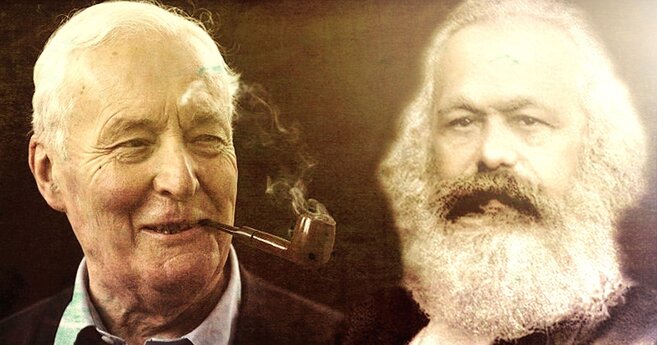

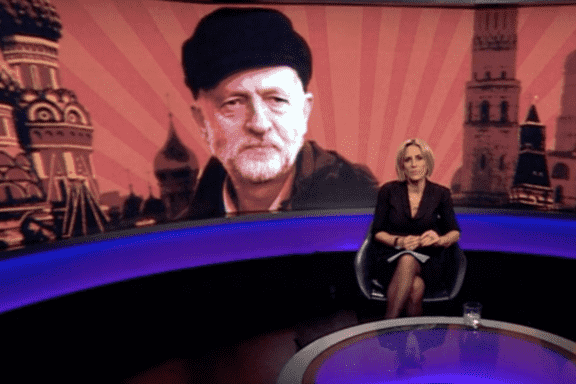

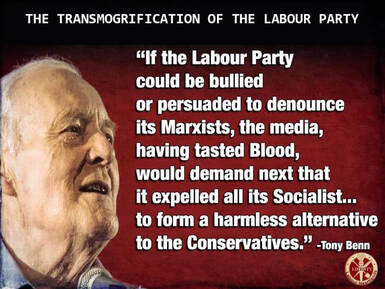

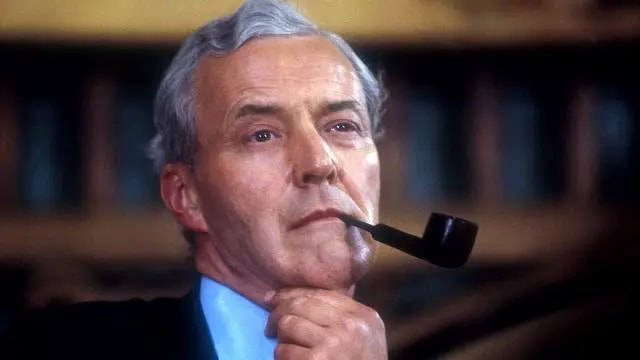

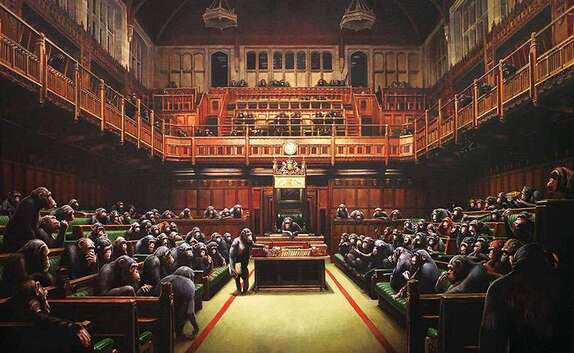

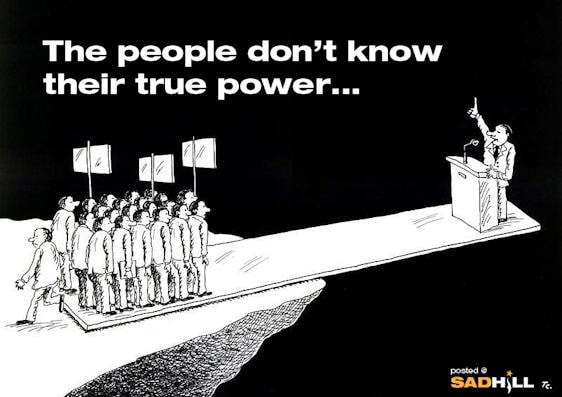

Tony Benn: Democracy and Marxism Tony Benn was one of the most distinctive political figures of the past 70 years. His views on the economy, The EU and foreign wars put him at odds with the political establishment and many within Labour, his own party. Tony Benn often gave us almost sage-like comments on society and the politics surrounding it, his speeches and talks reflected the deep richness of well thought out arguments delivered by a master orator. Tony Benn was a remarkable man with great gifts that he put at the service of his country. But just as importantly, and he would have emphasised this, he was in a tradition of radical socialists. He wanted his epitaph to be ‘He encouraged us’. It is from his works and reproduced speeches and writings many socialists find a little light and understanding. In his own words, Benn explains the dangers and repercussions of the Labour Party moving away from its core values and its Left-wing political doctoring’s. This resulted as we well know, in the collapse of the Labour Party under Blair, until it re-established its Left-wing credentials under Corbyn. Benn writes: “I am an example of someone who moved to the left as I got older. I have known many people who were very left-wing when they were young who ended up as Conservatives. But the experience of government made me realise that Labour was not engaged, as it said it was, in changing society but to make people change to get used to the society we had.” -Tony Benn. On the Blairites, a centrist political ideology that now forms the foundations of Sir Keir Starmer’s hollow ideology of Starmirisim, Tony Benn pointed out the collapse of public support for Blairism, and why: “We are paying a heavy political price for 20 years in which, as a party, we have played down our criticism of capitalism and soft-pedalled our advocacy of socialism.” He also said, as is today within the Labour party: “To be embarrassed by socialism was very much a characteristic of New Labour.” The Labour Party is once more heading down the road to nowhere, led by the centrists liberal elite, who have no real values or understanding of the working class and their aim to disassociate from the Labour Parties Marxist traditions is underway, we thought now would be a timely reminder of the Labour Parties association with Marxism and a little understanding of the Labour Parties roots, after all its founder Keir Hardie was a Marxist. While Sir Keir Starmer openly attacks the Left within the Labour Party and is busy digging those foundations up, an act that very much looks like his true intent is to bring the entire house down. We bring to your attention the words of Tony Benn in his address in 1982 ‘Marxism Today,’ a theoretical magazine of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Benn was articulating a theory very different from anything said by a leading politician before. It was also, clearly subversive. Article By Tony Benn May 1982 Marxism Today Marxism has only had a limited influence in the British Labour movement: but it will play a crucial role in its future. Tony Benn Though I was not introduced to socialism through a study of Marx, and would not describe myself as a Marxist, I regard it as a privilege and an honour to have been invited to deliver this Lecture in memory of Karl Marx. The intellectual contribution made by Marx to the development of socialism was and remains absolutely unique. But Marx was much more than a philosopher. His influence in moving people all over the world to social action ranks him with the founders of the world’s greatest faiths. And, like the founders of other faiths, what Marx and others inspired has given millions of people hope, as well as the courage to face persecution and imprisonment. Since 1917, when the Bolsheviks came to power in the Soviet Union, we have had a great deal of experience of national power structures created in the name of Marxism, and of the achievements and failures of those systems. Some of the sternest critics of Soviet society also based themselves upon Marx, including Leon Trotsky, Mao Tse-Tung, Tito and a range of libertarian Marxist dissidents in Eastern Europe and Eurocommunists in the West. This Lecture is concerned with only two aspects of Marxism.First, the challenge which Marxism presents to liberal capitalist societies which have achieved a form of political democracy based upon universal adult suffrage: and second, the challenge to those societies, which have based themselves on Marxism by the demands for political democracy. It is, I believe, through a study of this mutual challenge that we can get to the heart of many of the problems now confronting the communist and the non-communist countries, and illuminate the conflicts within and between different economic systems and between the developed and the developing world. Before I begin, let me make my own convictions clear. ⦁I believe that no mature tradition of political democracy today can survive if it does not open itself to the influence of Marx and Marxism. The evolution of British democracyIf an understanding of socialism begins — as it must — with a scientific study of our own experience, each country can best begin by examining its own history and the struggles of its people for social, economic and political progress. British socialists can identify many sources from which our ideas have been drawn. The teachings of Jesus, calling upon us to ‘.Jove our neighbour as ourselves’ acquired a revolutionary character when preached as a guide to social action. For example, when, in the Peasants Revolt of 1381, the Reverend John Ball, with his liberation theology, allied himself to a popular uprising, both he, the preacher, and Wat Tyler, the peasant leader, were killed and their followers scattered and crushed by the King. John Ball, one of the leaders of the Peasants‘ Revolt in England. The message of social justice, equality and democracy, is a very old one, and has been carried like a torch from generation to generation by a succession of popular and religious movements, by writers, philosophers, preachers, and poets, and has remained a focus of hope, that an alternative society could be constructed. The national political influences of these ideas was seen in 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, and in the revolutions in England, America, France and Russia, each of which provided an important impetus to these hopes. But it was the Industrial Revolution, and the emergence of modern trade unionism in the 19th century which provided a solid foundation of common interest upon which these Utopian dreams could be based, that gave the campaigns for political democracy and social advance their first real chance of success. If British experience is unique — as it is — in the history of the working class movement, it lies in the fact that the Industrial Revolution began here, and gave birth to the three main economic philosophies which now dominate the thinking of the world. The first was capitalism. Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations, developed the concept of modern capitalism as the best way to release the forces of technology from the dead hand of a declining and corrupted feudalism, substituting the invisible hand of the market and paving the way for industrial expansion and, later, imperialism. The Manchester School of liberal economists and the liberal view of an extended franchise combined to create a power structure which still commands wide support among the establishment today. The second was socialism. Robert Owen, the first man specifically identified as a socialist, also developed his ideas of socialism, cooperation and industrial trade unionism out of his experience of the workings of British capitalism. And the third was Marxism. Marx and Engels also evolved many of their views of scientific socialism from a detailed examination of the nature of British capitalism and the conditions of the working class movement within it. Yet, despite the fact that capitalism, socialism and Marxism all first developed in this country, only one of these schools of thought is now accepted by the establishment as being legitimate. Capitalism, its mechanisms, values and institutions are now being preached with renewed vigour by the British establishment under the influence of Milton Friedman. Socialism is attacked as being, at best, romantic or, at worst, destructive. And Marxism is identified as the anti-Christ against which the full weight of official opinion is continually pitted in the propaganda war of ideas. The distortion of MarxismBBC implied subliminal Corbyn wearing a Russian hat with a backdrop of the Kremilin. The term Marxist is used by the establishment to prevent it being understood. Even serious writers and broadcasters in the British media use the word Marxist as if it were synonymous with terrorism, violence, espionage, thought control, Russian imperialism and every act of bureaucracy attributable to the state machine in any country, including Britain, which has adopted even the mildest left of centre political or social reforms. The effect of this is to isolate Britain from having an understanding of, or a real influence in, the rest of the world, where Marxism is seriously discussed and not drowned by propaganda, as it is in our so-called free press. This ideological insularity harms us all. This continuing barrage of abuse is maintained at such a high level of intensity that it has obliterated — as is intended — any serious public debate in the mainstream media on what Marxism is about. This negative propaganda is comparable to the treatment accorded to Christianity in non-Christian societies. Any sustained challenge to the existing order that cannot be answered on its merits is dismissed as coming from a Marxist, Communist, Trotskyite, or extremist. All those suspected of Marxist views run the risk of being listed in police files, having their phones tapped and their career prospects stunted by blacklisting, just as those who advocate liberal ideas will be harassed in the USSR. Those who openly declare their adherence to Marxism are pilloried as self confessed Marxists, as if they had pleaded guilty to a serious crime and were held in custody awaiting trial. Even the Labour Party, in which Marxist ideas have had a minority influence, is now described as a Marxist party, as if such a statement of itself put the party beyond the pale of civilised conduct, its arguments required no further answer, and its policies are entitled to no proper presentation to the public on the media. One aspect of this propaganda assault which merits notice is that it is mainly waged by those who have never studied Marx, and do not understand what he was saying, or why, yet still regard themselves as highly educated because they have passed all the stages necessary to acquire a university degree. For virtually the whole British establishment has been, at least until recently, educated without any real knowledge of Marxism, and is determined to see that these ideas do not reach the public. This constitutes a major weakness for the British people as a whole. Six Reasons why Marxism is fearedThe People’s Charter Why then is Marxism so widely abused? In seeking the answer to that question we shall find the nature of the Marxist challenge in the capitalist democracies. The danger of Marxism is seen by the establishment to lie in the following characteristics. First, Marxism is feared because it contains an analysis of an inherent, ineradicable conflict between capital and labour — the theory of the class struggle. Until this theory was first propounded the idea of social class was widely understood and openly discussed by the upper and middle classes, as in England until Victorian times and later. But when Marx launched the idea of working class solidarity, as a key to the mobilisation of the forces of social change and the inevitability of victory that that would secure, the term ‘class’ was conveniently dropped in favour of the idea of national unity around which there existed a supposed common interest in economic and social advance within our system of society, whether that common interest is real or not. Anyone today who speaks of class in the context of politics runs the risk of excommunication and outlawry. In short, they themselves become casualties in the class war which those who have fired on them claim does not exist. Second, Marxism is feared because Marx’s analysis of capitalism led him to a study of the role of state power as offering a supportive structure of administration, justice and law enforcement which, far from being objective and impartial in its dealings with the people, was, he argued, in fact, an expression of the interests of the established order and the means by which it sustains itself. One recent example of this was Lord Denning’s 1980 Dimbleby Lecture. It unintentionally confirmed that interpretation in respect of the judiciary and is interesting mainly because few 20th century judges have been foolish enough to let that cat out of the bag, where it has been quietly hiding for so many years. Third, Marxism is feared because it provides the trade union and labour movement with an analysis of society that inevitably arouses political consciousness, taking it beyond wage militancy within capitalism. The impotence of much American trade unionism and the weakness of past non-political trade unionism in Britain have borne witness to the strength of the argument for a labour movement with a conscious political perspective that campaigns for the reshaping of society, and does not just compete with its own people for a larger part of a fixed share of money allocated as wages by those who own capital, and who continue to decide what that share will be. Fourth, Marxism is feared because it is international in outlook, appeals widely to working people everywhere, and contains within its internationalism a potential that is strong enough to defeat imperialism, neo-colonialism and multinational business and finance, which have always organised internationally. But international capital has fended off the power of international labour by resorting to cynical appeals to nationalism by stirring up suspicion and hatred against outside enemies. This fear of Marxism has been intensified since 1917 by the claim that all international Marxism stems from the Kremlin, whose interests all Marxists are alleged to serve slavishly, thus making them, according to capitalist establishment propaganda, the witting or unwitting agents of the national interest of the USSR. Fifth, Marxism is feared because it is seen as a threat to the older organised religions, as expressed through their hierarchies and temporal power structures, and their close alliance with other manifestations of state and economic power. The political establishments of the West, which for centuries have openly worshipped money and profit and ignored the fundamental teachings of Jesus do, in fact, sense in Marxism a moral challenge to their shallow and corrupted values and it makes them very uncomfortable. Ritualised and mystical religious teachings, which offer advice to the rich to be good, and the poor to be patient, each seeking personal salvation in this world and eternal life in the next, are also liable to be unsuccessful in the face of such a strong moral challenge as socialism makes. There have, over the centuries, always been some Christians who, remembering the teachings of Jesus, have espoused these ideas and today there are many radical Christians who have joined hands with working people in their struggles. The liberation theology of Latin America proves this and thus deepens the anxieties of church and state in the West. Sixth, Marxism is feared in Britain precisely because it is believed by many in the establishment to be capable of winning consent for radical change through its influence in the trade union movement, and then in the election of socialist candidates through the ballot box. It is indeed therefore because the establishment believes in the real possibility of an advance of Marxist ideas by fully democratic means that they have had to devote so much time and effort to the Even serious writers and broadcasters in the British media use the word Marxist as if it were synonymous with terrorismmisrepresentation of Marxism as a philosophy of violence and destruction, to scare people away from listening to what Marxists have to say. These six fears, which are both expressed and fanned by those who defend a particular social order, actually pinpoint the wide appeal of Marxism, its durability and its strength more accurately than many advocates of Marxism may appreciate. Marxism and the Labour PartyIf the Labour Party could be bullied or persuaded to denounce its Marxists, the media having tasted blood would demand next that it expelled all its socialists The Communist Manifesto, and many other works of Marxist philosophy, have always profoundly influenced the British labour movement and the British Labour Party, and have strengthened our understanding and enriched our thinking. It would be as unthinkable to try to construct the Labour Party without Marx as it would be to establish university faculties of astronomy, anthropology or psychology without permitting the study of Copernicus, Darwin or Freud, and still expect such faculties to be taken seriously. There is also a practical reason for emphasising this point now. The attacks upon the so-called hard Left of the Labour Party by its opponents in the Conservative, Liberal and Social Democratic Parties and by the establishment, are not motivated by fear of the influence of Marxists alone. These attacks are really directed at all socialists and derive from the knowledge that democratic socialism in all its aspects does reflect the true interest of a majority of people in this country, and that what democratic socialists are saying is getting through to more and more people, despite the round-the-clock efforts of the media to fill the newspapers and the airwaves with a cacophony of distortion. If the Labour Party could be bullied or persuaded to denounce its Marxists, the media having tasted blood would demand next that it expelled all its socialists and reunited the remaining Labour Party with the SDP to form a harmless alternative to the Conservatives, which could then be allowed to take office now and again when the Conservatives fell out of favour with the public. Thus, British capitalism, it is argued, would be made safe forever, and socialism would be squeezed off the national agenda. But if such a strategy were to succeed — which it will not — it would in fact profoundly endanger British society. For it would open up the danger of a swing to the far right, as we have seen in Europe over the last 50 years. Weaknesses of the Marxist positionBut having said all that about the importance of the Marxist critique, let me turn to the Marxist remedies for the ills that Marx so accurately diagnosed. There are many schools of thought within the Marxist tradition, and it would be as foolish to lump them all together as to bundle every Christian denomination into one and then seek to generalise about the faith. Nevertheless, there are certain aspects of the central Marxist analysis which it is necessary to subject to special scrutiny if the relationship between Marxism and democracy is to be explored. I have listed some of these aspects because of their relevance to this Lecture, and which explain in part why I would not think it correct to call myself a Marxist. Marx seemed to identify all social and personal morality as being a product of economic forces, thus denying to that morality any objective existence over and above the interrelationship of social and economic forces at that moment in history. I cannot accept that analysis. Of course, the laws, customs, administration, armed forces and received wisdom in any society will tend to reflect the interests and values of the dominant class, and if class relationships change by technology, evolution or revolution, this will be reflected in a change of the social and cultural superstructure. But to go beyond that and deny the inherent rights of men and women to live, to think, to act, to argue or to obey or resist in pursuit of some inner call of conscience — as pacifists do — or to codify their relationships with each other in terms of moral responsibility, seems to me to be throwing away the child of moral teaching with the dirty bathwater of feudalism, capitalism or clericalism. In saying this I am consciously seeking to re-establish the relevance and legitimacy of the moral teachings of Jesus, whilst accepting that many manifestations of episcopal authority and ritualistic escapism have blanked out that essential message of human brotherhood and sisterhood. I say this for many reasons. First, because without some concept of inherent human rights and moral values and obligations, derived by custom and practice out of the accumulated experience of our societies, I cannot see any valid reason why socialism should have any moral force behind it, or how socialism can relate directly to the human condition outside economic relationships; for example, as between women and men, black and white, or in the relationships within the home and in personal life. Second, because I regard the moral pressures released by radical Christian teaching, and its humanistic offshoots as having played a major role in developing the ideas of solidarity, democracy, equality and peace, which have contributed to the development of socialist motivation. Third, because without the acceptance of a strong moral code the ends always can be argued to justify the means, and this lies at the root of some of the oppression which has been practised in actually existing socialist societies. Fourth, because the teachings of Marx, like the teachings of Jesus, can also become obscured, lost, and even reversed by civil power systems established in states that proclaim themselves to be Marxist, just as many Christian kings and governors destroyed, by their actions, the faith they asserted they were sworn to defend. And if Jesus is to be acquitted of any responsibility for the tortures and murders conducted by the Inquisition, so must Marx be exonerated from any charges arising from the imprisonment and executions that occurred in Stalin’s Russia. Fifth, because without a real moral impulse and a warm human compassion, I cannot find any valid reason why Marx himself should have devoted so much of his time to works of scholarship and endless political activities, all of which were designed to achieve better conditions for his fellow creatures. That no doubt is why Marx is sometimes regarded as the last of the Old Testament prophets. If I am asked where these moral imperatives come from it not from the interaction of economic forces, my answer would be that they spring from the wells of human genius interacting upon our experience of life, which were also the sources of inspiration for Marx in his work. It is very important for many reasons that religion and politics should not be separated into watertight compartments, forever at war with each other. For centuries, the central social arguments and battles which we now see as political or economic, were conducted under the heading of religion. Many of the most important popular struggles were conceived by those who participated in them as being waged in pursuit of religious convictions. Similarly, some of the most oppressive political establishments exercised their power in the name of God. Unless we are prepared to translate the religious vocabulary which context of politics runs the risk of excommunication and outlawry. served as a vehicle for political ideas for so many centuries into a modern vocabulary that recognises the validity of a scientific analysis both of nature, society, and its economic interests, we shall cut ourselves off from all those centuries of human struggle and experience and deny ourselves the richness of our own inheritance. Marx and Marxist historians have, of course, consciously re-interpreted ancient history in the light of their own analysis, but no real dictionary can be restricted to a one-way translation based upon hindsight. We need a two-way translation to enable us to understand and utilise, if we wish to do so, the wisdom of earlier years to criticise contemporary society. It is in this context that I find some other aspects of Marxism unsatisfactory. Marx made much of the difference between scientific socialism and Utopian socialism, which he believed suffered from its failure to root itself in a vigorous study of the economic and political relationships between the social classes. The painstaking scholarship which he and Engels brought to bear upon capitalism has left us with a formidable set of analytical tools without which socialists today would have a much poorer theoretical understanding of the tasks which they are undertaking. But having recognised that priceless analytic legacy that we owe to Marx, in one sense Marx himself was a Utopian in that he appeared to believe that when capitalism had been replaced by socialism, and socialism by communism, a classless society, liberated by the final withering away of the state, would establish some sort of heaven on earth. Human experience does not, unfortunately, give us many grounds for sharing that optimism. For humanity cannot organise itself without some power structure of the state, and Marx seems to have underestimated the importance of Lord Acton’s warning that power ‘tends to corrupt’ mistakenly believing this danger would disappear under communism. Morality, accountability and the British labour movementTony Blair proclaimed that God will judge whether he was right to send British troops to war, echoing statements from his ally George Bush But we think while he is on this mortal realm a simple Inquiry would do. It is here that both the moral argument referred to above, and the issue of democratic accountability, which have both played so large a part in the pre-Marxist and non-Marxist traditions of the British labour movement, can be seen to have such relevance. For allowing for the weaknesses of Labourism, economism and the anti-theoretical pragmatism which have characterised the British working class movement at its worst, two of the beliefs to which our movement has clung most doggedly were the idea that some actions were ‘right’ and others were ‘wrong’; and to the obstinate determination to force those exercising political or economic power over us to accept the ultimate discipline of accountability, up to now seen mainly through the regular use of the ballot box, through which all adults would have their say in a universal suffrage to elect or dismiss governments. The British working class movement has over the years clung passionately to these twin ideas of morality and accountability in politics and they constitute the backbone of our faith. Some Marxists might argue that these objectives are too limited, are not specifically socialist, and constitute little more than a cover for collaborationist strategies which underpin bourgeois capitalist liberal democracy, complete with its soothing religious tranquillisers. I readily admit that a humanitarian morality and accountability are not enough, in themselves, to establish socialism, but they are essential if socialism is to be established, and if socialism is to be worth having at all. A socialist economic transformation may be achieved by force, but if so, it then cannot be sustained by agreement, and socialism may degenerate into the imposition of a regime administered by those whose attempts to maintain it can actually undermine it rather than develop it. The issue of parliamentary democracy How then, on this analysis, should we approach the arguments between the Marxist and some non-Marxist socialists which have in the past centred around their different assessment of the importance that should be attached to the role of parliamentary democracy? Before we can do that we have to examine, in some detail, what is meant by the phrase parliamentary democracy, for it lends itself to many definitions. Seen from the viewpoint of the establishment, Britain has enjoyed parliamentary government since 1295. All that has happened in the intervening period is that the Queen-in-Parliament has agreed to exercise the Crown’s powers constitutionally. This means accepting legislation passed ‘by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal in Parliament assembled’ and accepting that an elected majority in the House of Commons is entitled to expect that its leader will be asked to form an administration by the Crown; and that that administration will be composed of Her Majesty’s ministers, who in their capacity as Crown advisers will be free to use the Royal prerogatives to administer and control the civil and military services of the Crown. These democratic advances are circumscribed in four significant respects. First, in practice by the actual problems confronting an elected Labour government in establishing democratic control over the highly secretive self-directing and hierarchical executive of state power. Second, by the constitutional power of the Crown to dismiss a government and dissolve a parliament at any time. Third, by the fact that a government so dismissed, and a parliament so dissolved, lose all legal rights over the state machine and all legislative powers. Fourth, by the subordination of all United Kingdom legislation even when it has received the Royal Assent, to the superior authority of Common Market Law or Court judgements, which take precedence, under the European Communities Act, over domestic legislation, where the two conflict. It is worth noting that British accession to the EEC involved, in this sense, a major diminution of the powers of the Crown, in that Royal Assent to legislation rendered invalid by the EEC is itself invalid. Set out baldly like that, it can be seen that in a formal sense Britain is far less democratic in its form of government than those countries whose peoples may elect a President, both Houses of their Legislature and have entrenched their rights in written constitutional safeguards. Why then does the British labour movement appear to be so satisfied with our democratic institutions? In one sense, of course, it is not. The abolition of the House of Lords and the abrogation of British accession to the Treaty of Rome are amongst the items likely to feature high on the agenda for the next Labour manifesto. Those who call themselves revolutionary socialists and denounce the rest of us as nothing more than left-talking reformists, are not, in my judgment, real revolutionaries at all.I cannot hand away powers lent to me for five years by the people of Chesterfield The Labour Party just assumes that the Crown will always act with scrupulous care within the constitutional conventions that govern the use of the prerogative, and for that reason have never put this issue on its political agenda. Beyond that Labour believes that the reality of power precludes the possibility that our democratic rights might be overturned by an abnormal use of those formal powers which still reside in the non-elected elements of our constitution. In sharp contrast to the establishment view, Labour’s broad interpretation of the parliamentary democracy we have secured is that by a succession of extra-parliamentary struggles over the centuries the Crown was made accountable to parliament, the Lords were made subordinate to the Commons and the Commons were, through regular election, subordinated to the will of the electorate, made up first of men and later of women too, who have won, in fact, if not yet in constitutional theory, the sovereign rights which belong to the people — which is what democracy is all about. It is manifestly true that such an achievement, formidable as it is, falls short of a constitutional entrenchment of the sovereignty of the people, and that it secures no more than the right to dismiss governments and MPs and substitute new MPs and new governments. It certainly does not offer, of itself, any control over the extra-parliamentary centres of financial or economic power, which remain whichever government has been elected, or even guarantee ministerial or parliamentary power over the apparatus of the state. To that extent, democracy in Britain is still partial and political but not economic or social. But if, as I believe, the real strength of parliamentary democracy lies in the fact that the power to remove governments without violent revolution is now vested in the people, that is a very significant gain which should not be dismissed as being of little account, a fraud to be exposed, by-passed and replaced. One of the reasons why the British Labour Party and the British people are so suspicious of certain supposedly revolutionary schools of Marxist thought is that they believe that insufficient attention is paid by them to the importance of our democratic institutions, thus defined; and fear that if they were to be dismantled we should lose what we struggled so hard and so long to achieve. We would then be set back, perhaps with no gains to show for it. Parliamentary democracy is an evolving system, not yet fully developed, which enjoys wide support for what it has achieved so far. The myth of revolutionary activity in BritainUnlike other civil wars in England, which focused on who should rule, this war was more concerned with the manner in which the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland were governed. Given the fact that all our rights in parliament have been won by struggle, I must add that I have not observed any serious revolutionary movements pledged to destroy parliament anywhere across the whole spectrum of socialist parties of the Left in Britain today. Those who call themselves revolutionary socialists and denounce the rest of us as nothing more than left-talking reformists, are not, in my judgment, real revolutionaries at all. They are nothing more than left-talking revolutionists, who, while pointing to the deficiencies in our parliamentary democracy, offer themselves as candidates for parliament, and none of them are planning an armed revolution or a general strike to secure power by a coup d’etat. If such people do exist I have not met them, heard of them, or become aware of any influence they have in any known political party or grouping of the Left. Nor for that matter is there much hard evidence to suggest that there would be wide public support for a counter-revolution to topple an elected Labour government by force on the Chilean model. I appreciate that in playing down some of the most cherished fears of both ultra-Left and ultra Right, I am laying myself open to a charge of naivete, and depriving the mass media of one of their favourite and most spine-chilling horror myths, which they use to undermine public support for socialism. If there ever were to be a right wing coup in Britain it would not be carried out by paratroopers landing in central London, as it once seemed they would land in Paris just before de Gaulle came to power, but by an attempt to repeat what happened to Gough Whitlam when the Governor-General dismissed him as Prime Minister. And if the labour movement and the Left were ever to resort to force in Britain, it would not be to overthrow an elected government but to prevent the overthrow of an elected government, ie, in defence of, and not in defiance of, parliamentary democracy. It is, in this sense, and only in this sense, that the use of popular force would ever be contemplated by the labour and socialist movements. Raising the banner Labour Heartlands The role of extra-parliamentary activity.Though these may seem to be highly theoretical matters, it is necessary, to complete the analysis, to refer briefly to the varying circumstances in which popular action is legitimate. There is clearly an inherent right to take up arms against tyranny or dictatorship, to establish or uphold democracy, on exactly the same basis, and for the same reasons, that the nation will respond to a call to arms to defeat a foreign invasion, or repel those who have successfully occupied a part of our territory. In a different context, we accept certain more limited rights to defy the law on grounds of conscience, or to resist laws that threaten basic and long established liberties, as for example if parliament were to prolong its life, and remove the electoral rights of its citizens. The defence of ancient and inherent rights, as for example the rights of women, or of trade unionists, or of minority communities, could legitimately lead to some limited civil disobedience, accompanied by an assertion that the responsibility for it rested upon those who had removed these rights in the first place. And, at the very opposite end of this scale of legitimate opposition, lies the undoubted right to act directly to bring public pressure, from outside parliament, to bear upon parliament to secure a redress of legitimate grievances. Such extra-parliamentary activity has played a long and honourable part in the endless struggle to win basic rights. To assert that extra-parliamentary activity is synonymous with anti-parliamentary conspiracies is to blur a distinction that it is essential to draw with scientific precision if we are to understand what is happening and not to mistake a democratic demonstration for an undemocratic riot; a democratic protest for an undemocratic uprising; or a democratic reformer for an undemocratic revolutionary. The labour movement in Britain, egged on by a hostile media, is now engaged in a microscopic examination of its own attitude to the role of extra-parliamentary activity. Such an examination can only help to advance socialism. Perhaps the simplest way to understand these issues is to examine the attitude of the Conservative Party to the same issues. The Tory Party and its historical predecessors have never wasted a moment’s valuable time upon such constitutional niceties. Throughout our whole history, the owners of land, the banks and our industries, have been well aware that their power lay almost entirely outside parliament, and their interest in parliament was confined to a determination to maintain a majority there to Trotsky should be remembered as the first and most significant Soviet dissident, hunted and later murdered by Stalin. Leon Trotsky in November 1920, when still a key member of Russia’s new Soviet regime. Photograph: PA safeguard their interests by legislating to protect them. Extra-parlia- mentary activity has been a way of life for the ruling classes, from the Restoration, through to the overthrow of the 1931 Labour government, and the election in 1979 of Mrs Thatcher. In power they use parliament to protect their class interests and reward their friends. In opposition they use the Lords, where they always have a majority, to frustrate the Labour majority in the Commons, and supplement this with a sustained campaign of extra-parliamentary activity to undermine the power of Labour governments by investment strikes, attacks upon the pound sterling, granting or withholding business confidence, all using, when necessary, the power of the IMF, the multinationals and the media. Labour has real power outside parliament, and the people we represent can only look to an advance of their interests and of the prospects of socialism if Labour MPs harness themselves to the movement outside and develop a strong partnership which alone can infuse fresh life into parliament as an agent of democratic change. These matters and the associated issues of party democracy have received a great deal of attention within the labour movement over the last few years and it is not hard to see why. We want the Labour Party to practise the accountability it preaches. Seen in that light, the adherence of the labour movement to parliamentary democracy, and our determination to expand it, becomes a great deal more than a romantic attachment to liberal capitalist bourgeois institutions. By contrast, it can be seen to have a crucial role to play in achieving greater equality and economic democracy. The critiques of Leon Trotsky examined. Those who dismiss the role of parliamentary democracy, thus defined, can be seen to be engaged in weakening, rather than strengthening, the prospects of establishing a durable, democratic socialist society. In this context there are some within the Labour movement who have underestimated the potentiality of the democratic foothold which has been established in parliament. This misjudgment of what can be achieved is, in particular, associated with the school of thought inspired by Leon Trotsky, who rejected the Soviet system as it evolved after the death of Lenin, when Stalin imposed a rigid, centralised and ruthless tyranny in the name of socialism. Trotsky has had an immense influence on the world socialist movement, so much so that many different Trotskyite groups have been established. Trotsky should be remembered as the first and most significant Soviet dissident, hunted and later murdered by Stalin. His critiques of Stalinism merit respectful study and his contemptuous expose of the milk-and-water socialism of some Labour leaders in the 1920s in his book Whither Britain, entitles him to a place in our history. He was the first man to identify and warn against the betrayal of Ramsay Macdonald and to prophesy the birth of the SDP 55 years before it was formed. Moreover, he did urge the German Left to unite against the Nazis. But having said all that, Trotsky’s profound ambivalence about the nature of parliamentary democracy led him into error, both of judgment and of prescription. As I have said earlier, I do not believe that those socialists in Britain who claim to represent the views of Trotsky, are in any sense serious revolutionaries. They constitute schools of socialist thought whose ideas need to be discussed and argued over. In my view, the weakness of their argument lies in their underestimate of what has been and can be achieved, and the confusion which they perpetuate between the absence of actual reform and the inevitability that reform, if pressed, is bound to fail. The constraints on capital and the gains achieved by the trade union and labour movement over the years have been formidable. It is, I believe, a major error to argue that the advocacy of reform, rather than of revolution, is synonymous with betrayal and capitulation, for it undermines the very working class confidence which is central to the success of the movement, spreading pessimism about the prospects of victory — which is what the establishment has been trying to do for centuries. Some followers of Trotsky appear to substitute a ritualistic and dogmatic recitation of slogans which cannot connect with the life experience of those they are hoping to reach, thus minimising their public influence. Moreover, by suggesting that parliamentary democracy has only a limited role to play, and by speaking vaguely of direct action to bypass it, they seem to imply that socialism can be introduced by some industrial coup. They are also unacceptably vague about what would follow such an event if it ever occurred. Without the acceptance of a strong moral code the end always can be argued to justify the means.‘You talk about cancer? I feel very strongly about people whose entire life depends on the working class movement. Every office you held was because of Labour and then you left. Now that is a cancerous growth.’ Prescient words from Tony Benn on right-wing MPs Roy Jenkins and the SDP leaving Labour. This time they stayed and took over the Party But we must never forget that a socialist government that came to power by the exercise of industrial muscle, rather than by election, would be compelled to retain itself in office by a similar exercise of industrial power. Even if such a government could retain its formal control of all the instruments of state power, attacks by the forces marshalled against it by capital would rapidly intensify. Such forces would also be able to claim that, in the circumstances, they were also the champions of democracy. This combination of intense pressure from the dethroned domestic establishment, international capitalism and an angry electorate deprived of the traditional ballot box rights, would almost certainly overpower the new government and release counter-revolutionary forces on a massive scale, against which no effective democratic defence could be mounted, because all those who once believed in parliamentary democracy would have been demoralised by what had occurred. Having said all that, I am profoundly opposed to any attempt to outlaw, expel or excommunicate the followers of Leon Trotsky from the Labour Party. Some of them may, as I believe, be too simplistic in their analysis of Britain but, if so, the correct response is to discuss the issues with them, and within the labour movement these discussions are taking place and are exercising a mutual influence on those who take part on both sides. The main recruiting agents for Trotsky’s ideas in Britain have been those who have so cynically betrayed their faith in both socialism and democracy, while occupying high positions with the parliamentary Labour leadership, and then defected to the Social Democrats. These right-wing entryists used their positions as Labour MPs to obstruct the advance to socialism, and retain their seats in defiance of democracy. But no comment on the role of revolution would be complete without adding that what applies in the context of Britain, does not necessarily apply in countries that have not won the rights we have. The Russian people could never have won power through the Duma in Tsarist Russia, nor could the Zimbabwe Africans through Ian Smith’s rigged electoral system. The revolutionary route to democracy is almost certainly the only one open to the peoples of South Africa, Turkey, El Salvador and Chile, and many countries which the West so dishonestly classify as ‘our partners’ in the free world. Here in Britain, we have acquired, by struggle, precious democratic rights which we must defend and extend. I believe that communist countries could best evolve their socialism by consent if they studied and applied our experience. The problems that face a socialist government in Britain.In saying that, we also know that a Labour electoral victory, with a working majority on a socialist programme, could unleash tremendous opposition, including serious extra-parliamentary pressures. These will be formidable obstacles to overcome. Yet overcome them we must. Our best prospect of doing so lies, not in abandoning democracy, but in deepening it and widening it to win the public support upon which we shall have to rely. If we are to do that we must, above all, have confidence in the democratic process, and anyone who spreads doubts about its efficacy is abandoning the battle before it has even begun. At least we can comfort ourselves with the certain knowledge that however inadequate parliamentary democracy may seem to be to some in the labour movement, the establishment think otherwise. Socialist rhetoric they can live with easily, and revolutionary opportunism plays straight into their hands. But they know a real challenge when they see one and believe that parliamentary democracy, buttressed and sustained by a free, democratic and politically committed labour and trade union movement outside, can and will be strong enough to effect radical socialist reforms. Let me sum up this section on democracy and Marxism in Britain in this way. First, that Marxism occupies an integral part in our socialist tradition, and without it we should fail to understand the system we are seeking to change. Second, that the commitment of the British labour movement to parliamentary democracy, linked closely to the organisations of labour in the country, is not only right in principle but also offers the best way forward along the road to socialist transformation by consent. This is the process that the majority of the people of Britain have used, are using and must use to advance their interests. The experience of Marxist societies.I now want to turn to the experience of socialist societies founded by Marxist leaderships, and consider how they are responding to the pressure for democratic rights from their own people. It is an historical fact that such societies, almost without exception, emerged in countries which previously had no vehicle for peaceful transformation available. Russia1918 The Russian Revolution of 1917 against the Tsar took place against a background of war in a country without an established parliamentary democracy. The same was true of Yugoslavia, where the partisans liberated the country from the Germans and established a socialist state. In China the Communists fought against the Japanese invaders and the forces of Chiang Kai Shek who was backed by the USA. In Cuba socialism also emerged out of civil war against the dictator Batista. The socialist regimes in Eastern Europe came into being as a result of the war and were imposed by the USSR as part of its security policy to protect itself from attack after three invasions from the West — 1914, 1920 and 1941 — which had cost the lives of well over 20 million people. All that is a matter of historical record and those who took power by force could lay claim to the same legitimacy as was asserted by the American colonists in 1776, or the French revolutionaries in 1789. And this is the route followed by colony after colony as they won that freedom from undemocratic imperialist control. But the Stalinist distortion of Marxism created a political system that followed revolution based upon the theory of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. This followed on from a period under Lenin when Bolsheviks and Mensheviks were actually both represented in the Soviets. Under Stalin’s doctrine, the overthrow of capitalism by the working class had been undertaken by the Communist Party as the self-styled leadership of that class. However, this historical explanation of how the revolutions were planned and executed at the time does not end the matter. For socialism achieved by revolution lacks the explicit endorsement of the people, which is what democracy is about, and the Communist Parties which control such countries by limiting or denying basic rights of political expression, assembly, organisation and debate, and the right of the people to remove their governments, are open to the abuses of civil rights which occured under Stalin and continue today. Governments ruling by force — whether socialist or not — are also permanently vulnerable to violent upheaval and the task of liberalisation is difficult. And in a world of rapid communications, undemocratic regimes will find it increasingly hard to survive. It is very important for many reasons that religion and politics should not be separated into watertight compartments, for ever at war with each other. Picture: Fortepan/Pesti Srác licence: CC-BY-SA 3.0 Events in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, where Soviet troops were sent in to restore order after expressions of popular discontent, revealed this vulnerability, and undermined the claim of the Communist Parties there to enjoy majority support. Similarly, the imposition of martial law in Poland, though it may, in practice, have averted a Soviet invasion, has also confirmed the public unacceptability in Poland of the Communist regime as it was. The Western media make much of this, whilst ignoring the dictatorships which exist under the protection of the West. But above all, in the USSR itself, 65 years after the revolution, the maintenance of a government by state power — even when three generations have been born under communism, and only the very oldest people remember pre-revolutionary days — suggests, to outsiders, that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union does not itself believe that its leadership would receive popular endorsement. Yet the very refreshment of socialism must require at least a genuine public choice between alternative views as to how it should develop. Budapest Downtown with a Soviet Tank and the Head of the Previously Toppled Stalin Statue Socialism as a system is greatly weakened, worldwide, if it is seen to rest anywhere upon state enforcement. The forces of capital in the West have concentrated their attack upon democratic socialism — to good effect — by suggesting, quite falsely, that what is being advocated in the West involves the imposition of a Soviet-style regime upon our society and that the first election won by socialists would also be the last. They know it is not true, and it is a sign of the strength of socialist ideas that they have to pretend that they believe it. The British labour movement not only accepts the democratic process but claims, correctly, to have created it. We will never accept a socialism that is imposed. Liberalisation and detente and the emergence of Eurocommunism.The Soviet Union’s control of Eastern Europe — entrenched in the Brezhnev doctrine — is in fact based on security considerations for the USSR. If the pressure for political freedom is denied in these countries, and there are popular uprisings, then the Soviet Union may believe its security depends upon an intervention to suppress them, with the most serious international consequences up to, and including, the risk of nuclear war. Therefore, for practical reasons, a framework for the liberalisation of Eastern Europe should be developed which does not carry with it any threat to Soviet security. It is for this reason that the campaigns for European nuclear disarmament, a new pan-European security system to replace NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and for more economic cooperation between East and West, are so important. Liberalisation can only occur in an atmosphere of detente. The emergence of Eurocommunism in Western Europe offers us fresh hope here. The Italian Communist Party, for example, which accepts the need for a pluralistic political system, that guarantees the right of the electorate to replace communist governments in free elections, brings Eurocommunists back towards the mainstream of democratic socialism, and provides a direct link with the libertarian Marxists in the communist world. Here too, the British Communist Party and its programme The British Road to Socialism can be seen as pointing in a similar direction, and differentiates the party from its earlier and uncritical pro-Soviet stance which isolated it from the democractic traditions of the British labour movement. Socialism, democracy and Marxism The need for dialogue.In conclusion, may I make it clear that I believe a reconciliation of Marxism and political democracy is possible, necessary and urgent, if humanity is to solve the pressing problems which confront it and avoid the risk of war. But if we are to achieve that synthesis, there is much that needs to be done, and I suggest a draft agenda that we might use to guide us. First, the acceptance in the West of the importance of the socialist analysis of society within which Marxism must be seen as playing a key role. Second, the acceptance in the socialist societies of the principle of democratic accountability and full political rights as central to the practice of socialism. Third, the beginning of a regular series of structured national and international dialogues between socialists, Eurocommunists and Marxists of all schools of thought, to explore the relationship between democracy and Marxism and the experience of actually existing socialist parties and socialist societies. Fourth, the reunification of the world trade union movement, which was divided during the cold war when the ICFTU broke away from the WFTU, partly to permit a reunited world trade union movement to enter into the dialogue described above. To attempt these tasks will meet with powerful opposition even though they represent a very modest start for a process that will need to continue over a long period. For it is essential that an understanding of Marxism should become more widely available to strengthen the worldwide democratic movement, and that the practice of democracy be harnessed to protect the integrity of Marxism from the corruption of power which is inescapable under any system of government which seeks to impose itself without popular consent. If the peoples of the world are to end exploitation, reduce the levels of violence, avoid nuclear war, and enter into their rightful inheritance at last, we must achieve a synthesis of socialism and freedom and work for it here and now. -Tony BennThe collapse of the Labour vote has been a direct result of the party failing its founding principles, and the support of its traditional supporters. The seeds of decline were sown following Tony Blair as leader under the banner of New Labour, from which time the party lost its moral compass, the result of which only the Tories and the right-wing have ever benefited. The current bloodletting within the party is part of a blame game in which Jeremy Corbyn has become a scapegoat for the failure of the party membership, who have prioritised remaining in a neoliberal EU over principles and economic ideology. The insidious politics of the far right is able to exploit a vacuum of electoral participation by a confused electorate. It is against this background the Labour Party membership will have to assert with some urgency the revising of the principles on which it was founded in creating the politics of economic and social equality. Failure to do so will compound continued decline in electoral support. But to do this Labour members must carry out their own internal revolution and reclaim the Party or stay wedded to an authoritarian oligarchy in perpetuity. -Paul Knaggs. AuthorPaul Knaggs is an Editor, founder, Labour Heartlands, Labour Party member and activist. Citizen journalist, Ex-British Army combat veteran. Drifting towards Revolutionary socialism. Fighting a constant struggle with dyslexia that's overcome with a burning desire to speak out against the corrupt political system and the social injustices it creates. Advocate for Free speech and open, accountable, democracy. This article was produced by Labour Heartlands. Archives August 2021

1 Comment