|

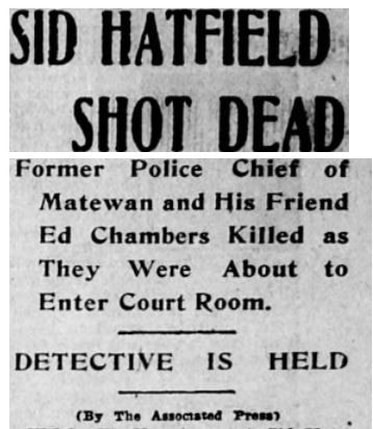

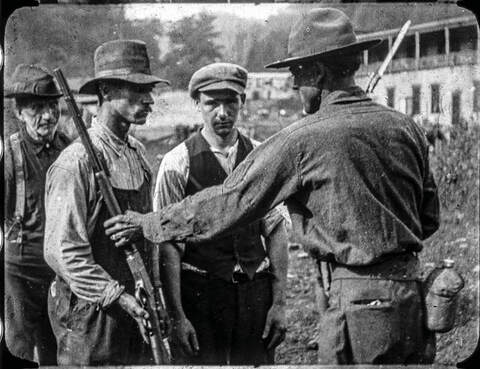

In late August of 1921, a militia made up of unionized West-Virginia coalminers began armed conflict with a private police force paid for by the wealthy mine owners who controlled the region’s politics. It ultimately became the largest labor uprising in United States history and the largest armed insurrection other than the Civil War. This was the Battle of Blair Mountain and it was the culmination of decades of labor struggles in Appalachia which boiled over into armed conflict on many occasions. Here I will provide a short history of the battle as well as the historical context that led to it. Like much of the rest of the U.S., Wester Virginia was largely composed of small, self-sufficient farms. Unfortunately for these farmers, they chose land on top of valuable coal deposits, and as American industrialization took off in the mid-19th century, so did its demand for natural resources to fuel it, making coal a valuable commodity. Thus, industrialists swarmed the hills of Appalachia gobbling up land by contesting deeds and using various other underhanded tactics to push poor families off their land. These newly landless masses would form the industrial proletariat which provided the labor power for the rapidly growing coal operators.[1] As the coal mines popped up so did the “Company Towns”. Ostensibly meant to provide services for the workers of these remote mines, company towns were actually the private fiefdoms of coal operators.[2] The entirety of the town, from the homes to the schools, were owned by the company, with workers being paid in “company scrip”- pieces of paper only redeemable at the “company store”. These were stores owned by the company where low-quality products were sold at inflated prices. Of course, this was not the only way the miners were fleeced. Coal operators utilized rigged scales, oversized containers, and various other methods to ensure miners did not receive the full wages they were owed for the coal they harvested. And, since housing was owned by the company, evictions happened on the whim of the owner. This hellscape was completed with private police to enforce these rules and discourage even the whisper of a union.[3] These conditions engendered plenty of resistance. Strikes occurred frequently in this period with many of them breaking out into violence. This is exactly what happened when the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike turned into open armed conflict. In 1912 miners associated with the United Mine Workers of America, District 17, went on strike demanding higher wages and recognition of their union, along with an end to mine guards, blacklisting, and restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly. Coal operators responded quickly, calling in hundreds of detectives from the private agency, Baldwin-Felts, to evict and intimidate workers. Additionally, coal operators imported “scabs” to replace the striking workers.[4] When miners were evicted, they set up tent colonies throughout the area. On February 7, 1913, the mine owners used an armored train outfitted with machine guns to open fire on one of these tent colonies in Holly Grove, fortunately only killing one miner. In response, the miners swiftly armed themselves and began engaging in guerilla warfare, ambushing mine guards near Holly Grove killing at least 12. When the violence failed to subside, West Virginia’s Governor, William Glasscock, declared martial law in the district three separate times, arresting over 200 miners and their allies including an 86-year-old Mother Jones, who had helped organize the strike. Over 100 of these people were court-martialed and sentenced to prison terms, but most of them were released by West Virginia’s next governor Henry D. Hatfield, although he kept the most radical strikers imprisoned. Hatfield followed this by imposing a settlement on the strike and closing socialist newspapers. While the settlement did not solve the underlying issues in the area, the conflict would have to be put on hold with the outbreak of World War I when many of the miners were drafted and new war-time restrictions were placed on unions.[5] After fighting in the most brutal war in history up to that point, the miners returned to a post-war slump, meaning lower wages and inconsistent work- not to mention the fact that war-time restrictions on union activity remained in effect. In 1920 the UMWA began an organizing drive in the southwestern part of the state that would last 28 months and include the Battle of the Blair Mountain. The drive began, and was relatively successful, in Mingo County where many towns, such as the small town of Matewan, had managed to remain free from company domination. Coal operators responded by locking miners out of the mines and beginning eviction proceedings. On May 19, 1920, Baldwin-Felts agents hired by coal operators began evicting families in Matewan. This was brought to a halt by the pro-union sheriff of Matewan, Sid Hatfield, who questioned the legality of the evictions and ordered the agents to leave town. However, before the agents could leave, Matewan mayor, Cabell Cornelius Testerman, issued an arrest warrant for the Baldwin-Felts agents for violating a city ordinance for carrying weapons. When Sheriff Hatfield confronted the agents with the warrant, they claimed they also had a warrant for Hatfield’s arrest, although they refused to produce it. Once Mayor Testerman was notified, he sent word that he would pay bond for Hatfield, but the agents claimed no bond would be accepted. Testerman then arrived on the scene, demanding to see the agents’ warrant which they produced. Testerman immediately declared the warrant to be a fake, leading to a shootout in between the agents and townspeople killing 7 Baldwin-Felts agents and 3 townspeople, including Mayor Testerman.[6] In the following months, clashes between the miners and police forces were frequent with miners engaging in acts of sabotage and ambushes of police agents. The police forces responded by attacking miners and shooting up tent villages. Martial law was declared three separate times with violence erupting again immediately after troops left. Finally, in the Spring of 1921, the governor instituted a draconian martial law heavily biased against the miners. In August of 1921, Sid Hatfield was summoned to McDowell county to answer charges for blowing up a coal tipple in the Spring. As Sid and his friend, Ed Chambers, walked up the courthouse steps, they were gunned down be Baldwin-Felts agents. Both men were unarmed.  This was the final straw for many mining communities in neighboring Logan County, who began agitating and organizing into armed patrols. Logan County was a coal operator stronghold, under the dominion of notorious anti-union sheriff, Don Chafin. In fact, upon his election, Chafin was given stock in coal companies amounting to between $700,000 to $840,000 in today’s money.[8] Logan county is split in two from north to south by the barrier of the Spruce Fork Ridge, which includes Blair Mountain. At the time, the western portion of the county was controlled by Don Chafin, while the eastern portion was a union stronghold. As miners began mobilizing, Chafin sent police to the town of Clothier where they arrested and assaulted a minor. The miners responded by ambushing and harassing several troopers before allowing them to leave. Miners began gathering at the state capitol of Charleston where they determined to go to Mingo to break the harsh martial law. Before miners could begin their march, U.S. President Harding sent Brigadier General Harry Bandholtz who negotiated a peace with representatives from the UMWA. Miners in Charleston decided to call of the march and return home. However, in miners in the Spruce River Valley shut down mines and fortified their locations, while miners in Clothier commandeered a train and began shuttling miners to Blair. Things remained peaceful until August 27, when Sheriff Chafin dispatched a force of over 300 police and detectives to Clothier to arrest the miners who had previously harassed his troopers. When they arrived in Clothier, they were confronted by a group of miners leading to a shootout where three miners were killed and three were arrested. This enraged miners who had begun returning home, leading them to regather and continue the march to Mingo.[9] Full open conflict began on August 31, with an estimated 10,000 miners attempting to march to Mingo and 3,000 police agents- mostly from Baldwin-Felts- seeking to stop the march from defensive positions fortified with machine guns. Being veterans of the First World War, the miners were a formidable force waging a highly coordinated and disciplined campaign. On September 1, Chafin even resorted to contracting private planes to drop bombs on the miners, although these bombings were largely ineffective. This open conflict and the possibility that miners might break through Chafin’s defensive positions instigated federal intervention. 2,100 federal troops were dispatched to the area and by September 4th fighting had ended, with an estimated death toll of 100 people. Miners had initially hoped the government would side with them but that was not to be. After the battle, 980 miners were arrested mainly for charges of treason and/or murder. While most of the farmers were acquitted, the legal fees incurred devastated the union, leaving it financially destitute for years to come.[10]  With this, the saga of Blair Mountain came to a close, with the UMWA decimated and the cola operators victorious. Despite their hopes that the Federal government would side with them, - especially given the veteran status of many of the miners- the government came down firmly on the side of the coal operators. This episode is just another instance revealing the role of the Bourgeois state: to protect capital from the demands of labor. The rights the miners were demanding would not be granted for another decade when the Roosevelt Administration adopted them as part of New Deal legislation. Although the miners failed in their immediate aims, they did manage to strike fear in the hearts of capitalists and gained national attention, setting a precedent for the limits to which workers can be pushed before they strike back. Citations. [1] Nida, B. Demystifying the Hidden Hand: Capital and the State at Blair Mountain. Hist Arch 47, 53–54 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03376908 [2] Richman, S. (2018, March 21). Company Towns Are Still with Us. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from https://prospect.org/economy/company-towns-still-us/ [3] Paul J. Nyden (Mar 01, 2007) Topics: Movements. “Rank-and-File Rebellions in the Coalfields, 1964-80.” Monthly Review, June 30, 2014. https://monthlyreview.org/2007/03/01/rank-and-file-rebellions-in-the-coalfields-1964-80/. [4] Nida, B. Demystifying the Hidden Hand: Capital and the State at Blair Mountain. Hist Arch 47, 55–56 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03376908 [5] “Share Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike.” encyclopedia. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1798. [6] Jansen-Montoya, Isaac. "The Battle of Blair Mountain." [7] “Sid Hatfield Shot Dead.” Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d. [8] Jansen-Montoya, Isaac. "The Battle of Blair Mountain." [9] Nida, B., and Adkins, M. J. (2011). The social and environmental upheaval of Blair Mountain: A working class struggle for unionization and historic preservation. In Smith, L., and Shackel, P. (eds.), Heritage, Labour, and the Working Classes, Routledge, London, pp. 52–68. [10] Jansen-Montoya, Isaac. "The Battle of Blair Mountain." [11] "AIR FLEET ORDERED TO W. VA. BATTLEFIELD." Washington Times [Washington D.C]. Library of Congress, chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1921-09-01/ed-1/seq-1/. About the Author:

I'm Alex Zambito. I'm born and raised in Savannah, GA. I graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 2017 with a degree in History and Sociology. I am currently seeking a Masters in History at Brooklyn College. My Interest include the history of Socialist experiments and proletarian struggles across the world.

1 Comment

Jonathan

1/22/2021 11:12:51 pm

Great summary. I'm a born and raised West Virginia with family on all sides having lived here for at least 4 generations. My grandfather's siblings were born and raised in coal camps until Blair Mountain drove his father out of coal mining. The people of this state have a long history of exploitation and organized resistance. Sadly, with the inevitable decline of the coal industry (once a source of great pride in the state) and the recent onset of the highly publicized opioid crisis, the people have abandoned their heritage in favor of the nationalist populism that plagues our country from the right. I hope that the current generation can reignite the passion for resistance and the battle for the working class. I fear, however, that the fragmentation of the working class leaves no direct opposition to rally against.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed