|

In October 2023, 10 members of the German parliament (Bundestag) left Die Linke (the Left) and declared their intention to form their own party. With their departure, Die Linke’s parliamentary group fell to 28 out of the 736 members of the Bundestag, compared to the 78 members of the far-right Alliance for Germany (AfD). One of the reasons for the departure of these 10 MPs is that they believe that Die Linke has lost touch with its working-class base, whose decomposition over issues of war and inflation has moved many of them into the arms of the AfD. The new formation is led by Sahra Wagenknecht (born 1969), one of the most dynamic politicians of her generation in Germany and a former star in Die Linke, and Amira Mohamed Ali. It is called the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance for Reason and Justice (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, BSW) and it launched in early January 2024. Wagenknecht’s former comrades in Die Linke accuse her of “conservatism” because of her views on immigration in particular. As we will see, though, Wagenknecht contests this description of her approach. The description of “left-wing conservatism” (articulated by Dutch professor Cas Mudde) is frequently deployed, although not elaborated upon by her critics. I spoke to Wagenknecht and her close ally—Sevim Dağdelen—about their new party and their hopes to move a progressive agenda in Germany. Anti-War The heart of our conversation rested on the deep divide in Germany between a government—led by the Social Democrat Olaf Scholz—eager to continue the war in Ukraine, and a population that wants this war to end and for their government to tackle the severe crisis of inflation. The heart of the matter, said Wagenknecht and Dağdelen, is the attitude to the war. Die Linke, they argue, simply did not come out strongly against the Western backing of the war in Ukraine and did not articulate the despair in the population. “If you argue for the self-destructive economic warfare against Russia that is pushing millions of people in Germany into penury and causing an upward redistribution of wealth, then you cannot credibly stand up for social justice and social security,” Wagenknecht told me. “If you argue for irrational energy policies like bringing in Russian energy more expensively via India or Belgium, while campaigning not to reopen the pipelines with Russia for cheap energy, then people simply will not believe that you would stand up for the millions of employees whose jobs are in jeopardy as a result of the collapse of whole industries brought about by the rise in energy prices.” Scholz’s approval rating is now at 17 percent, and unless his government is able to solve the pressing problems engendered by the Ukraine war, it is unlikely that he will be able to reverse this image. Rather than try to push for a ceasefire and negotiations in Ukraine, Scholz’s coalition of the Social Democrats, the Greens, and the Free Democrats, say Dağdelen, “is trying to commit the people of Germany to a global war alongside the United States on at least three fronts: in Ukraine, in East Asia with Taiwan, and in the Middle East at the side of Israel. It speaks volumes that Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock even prevented a humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza at the Cairo summit” in October 2023. Indeed, in 2022, Thuringia’s prime minister and a Die Linke leader, Bodo Ramelow, told Süddeutsche Zeitung that the German federal government must send tanks to Ukraine. When Wagenknecht called Gaza an “open-air prison” in October 2023, the Die Linke parliamentary group leader Dietmar Bartsch said that he “strongly distanced” himself from her (the phrase “open-air prison” to describe Gaza is used widely, including by Francesca Albanese, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian Territory occupied since 1967). “We have to point out what is happening here,” Dağdelen tells me, “It is our duty to organize resistance to this collapse of Die Linke’s anti-war stance. We reject Germany’s involvement in the U.S. and NATO proxy wars in Ukraine, East Asia, and the Middle East.” Controversies On February 25, 2023, Wagenknecht and her followers organized an anti-war protest at Brandenburg Gate in Berlin that drew 30,000 people. The protest followed the publication of a “peace manifesto,” written by Wagenknecht and the feminist writer Alice Schwarzer, which has now attracted over a million signatures. The Washington Post reported on this rally with an article headlined, “Kremlin tries to build antiwar coalition in Germany.” Dağdelen tells me that the bulk of those who attended the rally and those who signed the manifesto are from the “centrist, liberal, and left-wing camps.” A well-known extreme right-wing journalist, Jürgen Elsässer tried to take part in the demonstration, but Dağdelen—as video footage shows—argued with him and told him to leave. Everyone but the right-wing, she says, was welcome at the rally. However, both Dağdelen and Wagenknecht say their former party—Die Linke—tried to obstruct the rally and demonized them for holding it. “The defamation is intended to construct an enemy within,” Dağdelen told me. “Vilifying peace protests is intended to put people off and simultaneously mobilize support for repugnant government policies, such as arms supply to Ukraine.” Part of the controversy around Wagenknecht is about her views on immigration. Wagenknecht says that she supports the right to political asylum and says that people fleeing war must be afforded protection. But, she argues, the problem of global poverty cannot be solved by migration, but by sound economic policies and an end to the sanctions on countries like Syria. A genuine left-wing, she says, must attend to the alarm call from communities who call for an end to immigration and move to the far-right AfD. “Unlike the leadership of Die Linke,” Wagenknecht told me, “we do not intend to write off AfD voters and simply watch as the right-wing threat in Germany continues to grow. We want to win back those AfD voters who have gone to that party out of frustration and in protest at the lack of a real opposition that speaks for communities.” The point of her politics, Wagenknecht said, is not anti-immigration as much as it is to attack the AfD’s anti-immigrant stand at the same time as her party will work with the communities to understand why they are frustrated and how their frustration against immigrants is often a wider frustration with cuts in social welfare, cuts in education and health funding, and in a cavalier policy toward economic migration. “It is revealing,” she said, “that the harshest attacks on us come from the far-right wing.” They do not want, she points out, the new party to shift the argument away from a narrow anti-immigrant focus to pro-working-class politics. Polls show that the new party could win 14 percent of the vote, which would be three times the Die Linke share and would make BSW the third-largest party in the Bundestag. AuthorVijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and (with Noam Chomsky) The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power. AuthorThis article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives January 2024

3 Comments

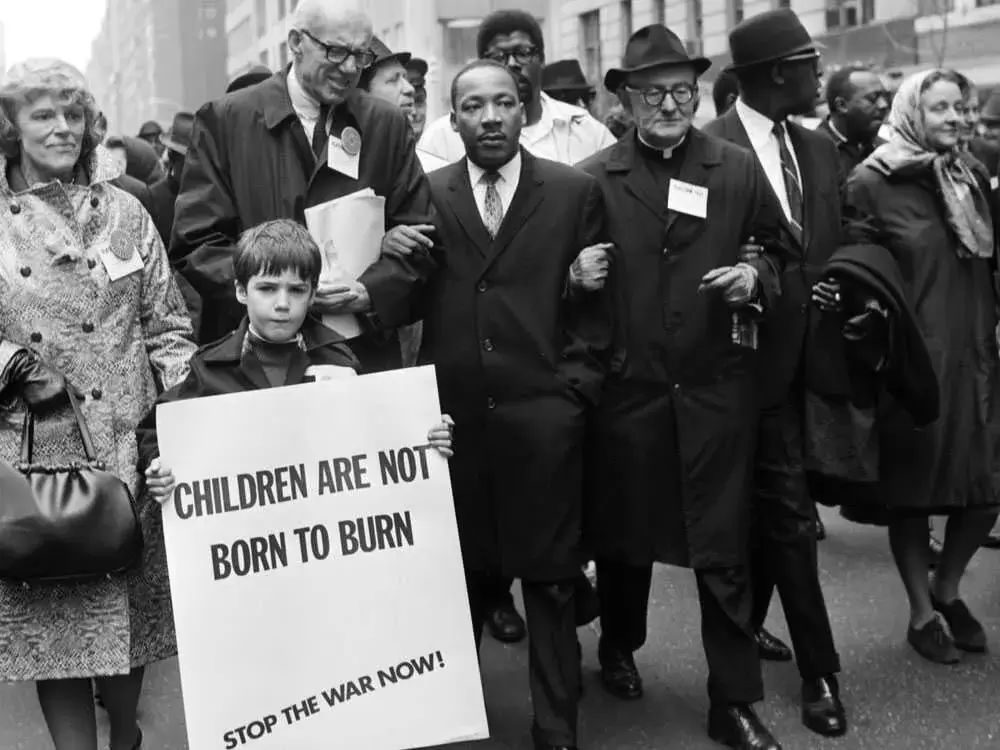

King marching against the Vietnam War. I am happy to see that more and more people are giving attention to the actual radical history of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the bastardization of his radicalism by the establishment in its attempt to neuter his lessons in radical activism. That being said, on what would be today his 95th birthday, it is clear the transformative visions he had for the country’s political, religious, social, and economic life are far from realized. As the genocide against Gaza enters its 101st day I think it is important we once again examine this American radicals legacy and how the actions of the United States, Israel, and seemingly the entire Western “civilized” world are completely contradictory to the values he lived by and the values our so called civilized societies claim to adopt. Beyond Vietnam April 4, 1967, exactly one year from when he would be assassinated, MLK spoke at Riverside Church in New York. This speech, titled “Beyond Vietnam — A Time to Break Silence”, was in opposition to the Vietnam war and how the genocidal killings abroad in Vietnam were apart of the struggle at home that Dr. King had been fighting against all of his life. It is a speech that the doctored version of MLK’s legacy often leaves out for it is filled with narratives that the established order wishes to bury. For instance, here is just one quote from the speech that shows MLK reflecting on the horrors of American foreign policy, horrors that may sound familiar to what we are seeing today. Dr. King speaking at Riverside Church April 4, 1967. “Hanoi remembers how our leaders refused to tell us the truth about the earlier North Vietnamese overtures for peace, how the president claimed that none existed when they had clearly been made. Ho Chi Minh has watched as America has spoken of peace and built up its forces, and now he has surely heard the increasing international rumors of American plans for an invasion of the North. He knows the bombing and shelling and mining we are doing are part of traditional pre-invasion strategy. Perhaps only his sense of humor and of irony can save him when he hears the most powerful nation of the world speaking of aggression as it drops thousands of bombs on a poor, weak nation more than eight hundred, or rather, eight thousand miles away from its shores.” — Martin Luther King Jr. King vehemently spoke out against the atrocities committed by the U.S in Vietnam. The actions of the U.S in Vietnam echo its actions in foreign policy today, including in its relationship with Israel and its collaboration in the genocide against the Palestinian people. On Trial for Genocide International Court of Justice hearing South Africa’s case. After nearly 100 days of gross violence against the civilian population of Gaza, one country finally has had enough and has taken to international law for some attempt at holding the murderers accountable. South Africa has taken a case to the ICJ (International Court of Justice) accusing Israel of genocide against the Palestinian people. Their case, to anyone with eyes and ears, recounts the enumerable war crimes committed by Israel against Gaza which include: Planned starvation, destruction of water sanitation plants, shutting down internet and power, displacing over 2 million people inside of an open air concentration camp, bombing everything from hospitals to bakeries, the list is exhaustive and never ending. Will this case amount to much? Not likely, even given the overwhelming evidence. No, like Dr. King astutely pointed out, America will lie about the overtures of peace from those who are sane. It will bribe the ICJ to rule against the possibility of genocide, or perhaps ignore any ruling altogether. It is still admirable that South Africa has gone to the international courts of law and asserted their humanity. South Africa not along ago was a nation mired by the scourge that is apartheid. That is why those who remember are making sure others will remember this genocide with stark clarity. Yemen’s Show of Solidarity Much noise has been made lately by the Yemeni rebel group the Houthis and their capturing of commercial ships in the Red Sea. The Houthis are the de facto ruling entity of Yemen since Saudi Arabia’s equally genocidal campaign began in 2014, a war that is funded and enabled by the United States as well. Yemenis are facing one of the greatest humanitarian crises in the world imposed on it by the U.S and its allies. Despite this the Yemenis are the ones capturing ships in solidarity with Gaza. The Houthis have explicitly said that this is their reasoning. That they will capture and disrupt ships in solidarity with the Palestinian people until the genocidal assault against Gaza has ended. Yemen, facing its own existential threats, has made a show of solidarity when no other country has. Yemen, like South Africa, understands what it means to face genocidal threats and what it means to stand against them. Actions of the USA U.S.A The U.S has acted as though its hands are tied with regards to Israel’s latest murderous campaign against Palestinians. Even though Israel could not functionally survive without U.S financial and military support, the U.S State Department acts as though Israel is its own entity. This veneer of incapability is dropped quickly with the latest strikes against the Houthi rebels in the Red Sea. To stop Israel’s genocide against Gaza is out of our power, but thwarting the capture of commercial shipping vessels is well within our reach. It is disgusting. 10,000 + children have been murdered. 25,000+ civilians. A whole percent of the population of Gaza has been obliterated. The U.S makes a parade of MLK in the culture. Unbeknownst to most, his true legacy as a radical is covered up. He is made a puppet of imperial interest. A black face for empire. Those who see clear see his legacy in speeches like “Beyond Vietnam”. They see the acts of South Africa and the Houthis as extensions of his philosophy outlined in these speeches. They see the acts of the United States remain in an evil stagnant way, as the words used by King to describe the crimes in Vietnam ring so true to the crimes we see perpetrated against Palestinians today. I’ve Been to the Mountaintop On April 3, 1968 whilst on a campaign to organize black sanitation workers outside Memphis, Tennessee, MLK made a speech at Mason Temple that is now titled “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” Aptly titled, this would be MLK’s final speech as he was shot the following day. MLK speaks with a tone fraught with danger reminiscent of corrido star Chalino Sanchez reading his death note before performing a final rendition of his “Alma Enamorada”. Hours before his plane had been subject to a bomb threat. Undeterred, MLK made it a point to show that he was not fearful, that he had “been to the mountaintop.” I’d like to end with a quote from this speech to remind us all what it means to stand for the downtrodden and oppressed. Sometimes this fight will cost us everything. That is the price of bearing witness and seeking justice. “And then I got to Memphis. And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers? Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land” — Martin Luther King Jr. Mural of Shireen Abu Akleh, a longtime Al Jazeera journalist who was shot and killed by an IDF sniper, a fact which was denied by Israel for many months. AuthorThis article was produced by Medium. Archives January 2024 1/28/2024 Palestine notes: How Europe projected its unique antisemitism disease on the Middle East By: Palestine Will Be FreeRead NowA quick chat designed to tell you something you need to know about the politics surrounding Palestine. Name: European antisemitism. Age: Centuries old. Appearance: Earlier, it looked like Jewish persecution by Christians in Europe; now, it’s anything and everything that Israel and the Zionists disagree with. Are you telling me antisemitism is a uniquely European phenomenon? Yes, 100 percent. Jews dispersed across the world after their expulsion from Jerusalem over 2 millennia ago and encountered marginalisation and outright hostility in Europe. They were forced to live in ghettos and faced episodic violence, which, at times, amounted to pogroms. Then the Nazis under Hitler went on a never-seen-before genocidal slaughter of the Jews beginning in the early 1940s with the express aim of getting rid of all Jews in Germany. If the Europeans were terrible to the Jews, I am sure non-Europeans were no better. Or are you telling me the Jews were safe in other places? The Jews certainly didn’t face persecution in the Middle East, including in historic Palestine — in fact, in any of the Muslim-ruled lands — where they lived alongside the indigenous Muslim and Christian populations. What are you saying? Aren’t Muslims virulently antisemitic? Caitlin Johnstone recently wrote: “The greatest trick white anti-semites ever pulled was getting Jews to leave western society and move to a foreign country to spend their lives beating up Muslims.” I would argue that the second-greatest trick the white antisemites ever pulled was imposing upon the non-Europeans the notion that they were also antisemitic just like them. Since you are making such bold claims, I am sure you have evidence to back them. Of course I do. Examples of Muslims’ peaceful coexistence with Jews abound. Jews flourished not just in the Middle East but also in Muslim-ruled Spain (711-1492). I will tell you the incredible story of Samuel HaNagid (also known as Samuel ibn Naghrillah and Isma’il ibn Naghrilla). HaNagid was a Talmudic scholar, poet, and warrior who ruled Muslim Granda for 2 decades and led the Muslim armies in battle against invading Christian forces. In an introduction to his book Selected Poems of Shmuel HaNagid, Peter Cole writes: “The first major poet of the Hebrew literary renaissance of Moslem Spain, Shmuel Ben Yosef Ha-Levi HaNagid (993-1056 c.e.) was also the Prime Minister of the Muslim state of Granada, battlefield commander of the non-Jewish Granadan army, and one of the leading religious figures in a medieval Jewish world that stretched from Andalusia to Baghdad.” Wait, a Jewish Prime Minister in a Muslim state?! Did I get that right? Yes, you got that exactly right. In his book, Cole writes: “He [HaNagid] successfully led Badis's [the King of Granda] forces into battle for sixteen of the next eighteen years, serving either as field commander or in a more administrative and Pentagon-like capacity as minister of defense, or chief of staff. In his various public roles HaNagid helped establish Granada as one of the wealthiest and most powerful of the thirty-eight Taifa or Party States of Andalusia, and he continued to serve both Moslem and Jewish communities until he died.” That’s an incredible story. Wait till you hear about Moses Maimonides. Now, who’s that? Also known as Rambam, Maimonides is widely considered among the greatest Jewish scholars. He was born in Muslim Spain and flourished there. A polymath, he served as Saladin's personal physician! Yes, the Saladin. The man who decisively conquered Jerusalem from the marauding Crusaders and kept them at bay. Can you imagine a Christian ruler of Saladin’s stature trusting a Jewish doctor for his health in the medieval era? I can’t. I know. You know what happened at the coronation of Richard the Lionheart of England, Saladin’s rival in the unsuccessful Third Crusade for the conquest of Jerusalem? No. What? Pogroms against Jews. Oh! I should have guessed. I am glad you are starting to see a pattern in the historic European contempt for Jews. Although, to his credit, Richard is reported to have been incensed by the violence. Anyway, let me continue my story about the Jews in Muslim lands. When Ferdinand and Isabella took charge in Spain following the Reconquista in 1492, they issued the Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion). It required the Jews in Spain to either convert to Christianity or leave Spain. Over 13,000 Jews were executed following the Christian reconquest of Spain. Those who fled were welcomed by the Ottoman sultan Bayezid II to settle in the Muslim Ottoman lands. Moreover, Bayezid II didn’t just welcome the fleeing Jews; he arranged for his navy to bring them to his lands. According to an article in the Israeli outlet 972: “In August 1492, he sent his navy to Spain to evacuate the expelled Jews to the empire, where he granted them permission to settle and become citizens.” Perhaps because of his awareness of Christian attitudes towards the Jews, Bayezid II “sent a special decree to the governors of his European provinces, ordering them to receive the Jewish refugees well.” Historian Firas Alkhateeb writes in his book Lost Islamic History: “Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II ordered his military and governors to welcome any Jewish refugees from Spain. A sizeable Jewish community descended from these Spanish Jews remained in Istanbul until the twentieth century.” On the Muslim generosity towards the Spanish Jews, one Turkish historian wrote: “In the Ottoman mind, Spain was a major antagonist, and the Ottomans made little distinction between the plight of the Andalusian Muslims and that of the Jews when both communities were threatened by Spain, and both appealed for Ottoman aid and protection.” In short, the Ottomans made no distinction between the persecuted Muslims and the persecuted Jews. Oh! And do you know when the Spanish formally rescinded their expulsion order? No, I don’t. On December 16, 1968, after more than 476 years! Those were medieval times. I am sure the Muslim-Jew ties would have been strained later. Not at all. In fact, when the Nazis were hunting Jews, there were recorded instances of Muslims doing all within their means to save Jews in Europe. Take, for example, Si Kaddour Benghabrit, the Imam of the Grande Mosque de Paris during the Nazi occupation of France in World War II. He “led a clandestine effort that offered protection, shelter, and travel assistance to about 1,700 French Jews after the Nazis and the Vichy government began targeting the community for deportation to Auschwitz.” On July 16, 1942, when the French collaborationist government sent 13,00 Jews to Auschwitz, these words of the Imam were read throughout immigrant hostels in Paris the very next day: “Yesterday at dawn, the Jews of Paris were arrested. The old, the women, and the children. In exile like ourselves, workers like ourselves. They are our brothers. Their children are like our own children. The one who encounters one of his children must give that child shelter and protection for as long as misfortune — or sorrow — lasts.” And the Imam wasn’t the only Muslim attempting to save Jews from the Nazis. Mustafa and Zejneba Hardaga, Ali Sheqer Pashkaj, and Nuro Hoxha were among the many, many conscientious European Muslims who did their best to save Jews from the gas chamber. Moreover, it was the Muslims of Palestine who gave the fleeing European Jews refuge in their own homes at the height of the Nazi pogroms. Their current Western benefactors had deserted them and were turning away ships full of fleeing Jews, preventing them from landing on their shores, but the Muslims opened their arms. Take, for example, the story of the St. Louis ship carrying over 900 fleeing Jewish refugees. They reached Canada in 1937 but were turned away. The Canadian government apologised only in 2018 for its inhuman act. “We apologise to the 907 German Jews aboard the St. Louis, as well as their families,” Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said. “We are sorry for the callousness of Canada's response. We are sorry for not apologising sooner.” One should take Trudeau’s apology with a sack full of salt, considering he and his fellow Canadian parliamentarians just this year gave a Ukrainian Nazi standing ovation. What happened to the passengers of the ship? They tried landing in the United States. But I am sure it won’t surprise you when I tell you that the United States also turned the refugees away. They were forced back to Europe, and a third of the passengers were murdered. Moreover, shortly after turning the ship away, the US rejected a proposal to allow 20,000 Jewish children to come to the US for safety. But Muslims were different? Yes, they were. Arab Muslims, especially in Palestine, treated the Jews as fellow Semites and welcomed them into their own homes, which, to their great surprise and utter misfortune, were taken over by the once-refugees. The welcoming Muslims had now become refugees. Mohamed Hadid, the father of models Gigi and Bella, had his family kicked out of their home in Safed, Palestine, in which his father had hosted two European Jewish families. He recently recounted his family trauma: “When I was only nine days old, my mother, taking my two-year-old sister with her, returned to our home in Safed. Safed had almost been taken over by the Jewish residents there. My father, a professor at Haifa University, was also not at home. When we arrived at the part of our home that belonged to my mother and our family, they did not let us in.” Unfortunately, the Hadids aren’t an aberration. Historic Palestine is full of stories like that of the Hadids. Do the Jews acknowledge the generosity of Muslims towards them? Israelis and their supposed sympathisers in the West have tried hard to whitewash the story of the 1948 Nakba, in which over 750,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes, more than 15,000 were murdered in over 50 massacres carried out by Zionist terrorists, and 500 of their villages were ethnically cleansed. However, there are some Israelis with a conscience. Even a former Haganah terrorist acknowledged the Muslim contribution to the survival of Jews over the ages. The late Uri Avnery, who was also a member of the Knesset (the Israeli parliament), once wrote: “Every honest Jew who knows the history of his people cannot but feel a deep sense of gratitude to Islam, which has protected the Jews for fifty generations, while the Christian world persecuted the Jews and tried many times ‘by the sword’ to get them to abandon their faith.” All of this is news to me. Unfortunately, the European propaganda to paint Muslims in general and those of the Middle East in particular as antisemitic savages as a way to shift their guilt has led to the concealment of the cordial relations between Muslims and Jews throughout history. I am sure the Zionist transgressions since the late 19th century, especially from 1948 onwards, have not helped matters either. No, they haven’t. However, Palestinians haven’t lost sight of the fact that their enemy is the violent racist death cult of Zionism and not Judaism. And as Joseph Massad has cogently argued, Palestinians are the last of the Semites bravely resisting antisemitism. The Columbia University Professor writes: “The Jewish holocaust killed off the majority of Jews who fought and struggled against European anti-Semitism, including Zionism. With their death, the only remaining ‘Semites’ who are fighting against Zionism and its anti-Semitism today are the Palestinian people. Whereas Israel insists that European Jews do not belong in Europe and must come to Palestine, the Palestinians have always insisted that the homelands of European Jews were their European countries and not Palestine, and that Zionist colonialism springs from its very anti-Semitism. Whereas Zionism insists that Jews are a race separate from European Christians, the Palestinians insist that European Jews are nothing if not European and have nothing to do with Palestine, its people, or its culture. What Israel and its American and European allies have sought to do in the last six and a half decades is to convince Palestinians that they too must become anti-Semites and believe as the Nazis, Israel, and its Western anti-Semitic allies do, that Jews are a race that is different from European races, that Palestine is their country, and that Israel speaks for all Jews. That the two largest American pro-Israel voting blocks today are Millenarian Protestants and secular imperialists continues the very same Euro-American anti-Jewish tradition that extends back to the Protestant Reformation and 19th century imperialism. But the Palestinians have remained unconvinced and steadfast in their resistance to anti-Semitism.” I agree with Mr. Massad. He’s hard to argue against. By the way, even the children of Palestine bear no ill will toward the Jews despite the Israeli butchery they have witnessed for their whole lives. They are smart enough to differentiate between Zionist terrorism that is ruining their lives and the ancient faith of Judaism. The intact moral compass of Palestinian children was reflected in Max Blumenthal’s tribute to Refaat Alareer following his assassination by the Israeli terrorists in early December. Blumenthal writes: “Refaat also assigned his students The Merchant of Venice. He encouraged the class to view Shylock, Shakespeare’s Orientalized, avaricious Jewish character, as a sympathetic figure who was struggling to retain a modicum of dignity under an apartheid-like regime. “When his students completed the play, Refaat asked them which Shakespearean character they sympathized with more: Othello, the Venetian general of Arab origin, or Shylock, the Jew. He described their response as the most emotional moment of his six-year teaching career: One by one, his students declared an almost visceral identification with Shylock. “In her final paper, one of Refaat’s students reworked Shylock’s famous cri de coeur into an appeal to the conscience of her own oppressors: “Hath not a Palestinian eyes? Hath not a Palestinian hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer as a Christian or a Jew is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” Do say: “Wow! Muslims have been so cool with the Jews throughout history and continue to be so.” Don’t say: “Let’s learn history exclusively from Western textbooks and Western leaders and Western media.” AuthorThis article was produced by PALESTINE WILL BE FREE Archives January 2024 1/21/2024 Five of Lenin’s Insights That Are More Pertinent Than Ever. By: Carlos L. GarridoRead Now