|

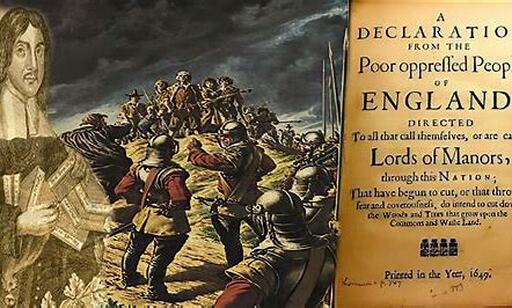

4/30/2021 Antonio Gramsci and Political Praxis in the Materialist Theory of History. By: Sebastián LeónRead NowIn commemoration of the 84th anniversary of his death. Antonio Gramsci is one of the most relevant theorists in the history of Marxism - he is also one of the most misunderstood. Self-proclaimed heterodox leftists of all latitudes have made “neogramcism” their banner, finding in the Sardinian revolutionary a symbol of the break with real socialism, Marxism-Leninism and the materialist theory of history. Perhaps the best known figure in this intellectual trend has been the Argentine Ernesto Laclau, who once again made a key concept such as hegemony fashionable in the academic mainstream. Laclau defined his neogramscism as "post-Marxist", having completely abandoned historical and dialectical materialism, and conceived of social reality as a fundamentally discursive, unstable and radically contingent construct, in which the different forces dissatisfied with the present social arrangement could, through the elaboration of highly porous ideas and slogans, join a political force capable of challenging the common sense of society to the powers that be (that is, hegemony). Here, the conquest of socialism and communism gave way to a "radical democracy", in which every area of social life was left open to democratic deliberation to reconfigure the established order. It is necessary to differentiate Laclau, as well as other self-proclaimed “neo-Gramscians” and followers of Gramsci (whether they are “post-Marxists” or “heterodox Marxists”), from the man himself. For, although there are many who seek to decouple Gramsci and his thought from Marxism-Leninism, his effort cannot be understood if it is not as the attempt of a communist, committed to the revolutionary spirit of the October Revolution, to bring Marxist theory to life in territories that had previously remained unexplored. For, if the Bolshevik triumph had captured the imagination and hopes of Gramsci and a whole generation of Western revolutionaries, the reality of post-World War I Europe forced them to confront failure and the rise of reaction. Gramsci the Bolshevik One of the things that is fascinated about Gramsci is the extent to which he emphasizes the role of subjectivity and political will over the relentless inertia of the relations of production and the productive forces. There are those who think that the construction of socialism and emancipation has more to do with the will of human beings than with the creation of certain material conditions that make it possible; however, one must understand the weight that Gramsci gives to the subjective dimension of politics in its context. The Bolshevik triumph in Russia represented for him “the rebellion against Marx’s Capital ”, insofar as it embodied the triumph of a Marxism (that of Lenin) that came to be understood fundamentally as“ concrete analysis of the concrete situation ”with a view to the strategic organization of political action, over the positivist orthodoxy of the Second International, which clung to a linear and evolutionary model of history, in which the backward countries had to largely imitate the history of the West (necessarily having to go through industrial capitalism and the formation of liberal democracy before attempt a socialist revolution) before making their own. The Social Democrats of the Second International would place their hands on their head with the events in Russia, where the popular masses - mostly peasants - carried out the first successful socialist revolution of the 20th century. These events would profoundly mark a socialist like Gramsci, whose homeland was part of the southern periphery of Europe. However, none of this implied a voluntaristic understanding of politics: on the contrary, the Italian communist understood perfectly that the possibility of the Russians to create a socialist society was anchored in the availability of advanced technical-scientific resources in other parts of the world, which could be implemented by the communists to develop their productive forces without handing over the reins of government to the bourgeoisie. The emphasis on revolutionary organization and will did not imply a disregard for the objective conditions that constrained them; on the contrary, the consideration of these conditions should give rise to a form of collective action that found in the present an opportunity to make history, without applying abstract schemes alien to the singularity of the context. If Gramsci emphasized the weight of human agency, it was always from the coordinates of Leninism, which he saw as a truly dialectical materialism, which marked a distance with a mechanistic materialism, as harmful to revolutionary theory as voluntary idealism. Civil society, hegemony and historical bloc However, the context that the Italian Communists would have to face would be very different from the Russian one. With the rise of fascism, Gramsci, who had become head of the CPI and had been elected deputy, would be put in prison, and would remain there practically until the end of his short life. It would be there where he would elaborate the bulk of his theoretical writings, gathered in the famous volume known as The Prison Notebooks. In his writings from this stage of his life, Gramsci touches on a host of highly relevant topics, from history and economics to politics and philosophy, passing through education and culture. However, if there is an axis that articulates this scattered compendium, this will be the problem of the defeat of socialism in Europe (in particular, in Italy): why had the winds of change coming from the East finished evaporating? And why had the bourgeois reaction managed to take hold where socialism and the working class had failed? It is from this fundamental concern that Gramsci's interest in the question of hegemony arises. In his opinion, the dominance of the capitalist class over the whole of society could not be understood if it was reduced exclusively to a form of violent coercion (political or economic); rather, the power of it was to be thought of as an articulation of coercive force and persuasion. The first would correspond to what Gramsci called "political society": the strictly coercive apparatuses of the State, such as the legal apparatus, the armed forces, the police, etc. However, the second would correspond to “civil society”, which was rather the space of consensus and persuasion, where the beliefs, values and norms shared by the different members of a society were produced: the family environment, educational and religious institutions, the media, unions, etc. It was in the context of thinking about the formation of this sociocultural "common sense" that Gramsci recovered and expanded the Leninist concept of hegemony, which would come to refer to the political domain of a social class (the bourgeoisie), anchored in its pact with other social classes (such as the petty bourgeoisie) and their undisputed control of the cultural field, making common sense of their particular interests and worldview. From his point of view, it would have been this form of hegemonic control, and not its coercive power, that would have allowed the bourgeoisie to subdue the progressive forces of the continent and strengthen its dominance. It would be these theoretical elaborations that would lead Gramsci to take an interest in fields that Marxist theory had typically relegated to a more marginal place, such as the culture, tradition and faith of the popular classes. From his point of view, the Bolshevik triumph in Russia, as it had occurred in the context of war, had only been possible because the aristocratic and bourgeois elites had not managed to consolidate hegemony, and this allowed Lenin and the Bolsheviks to win in a war of maneuvers (basically, defeating them in an open confrontation in the period of the Russian Civil War). On the other hand, where the hegemony of the bourgeoisie and its allies was entrenched, the only way to seize political power and transform the relations of production was through the formation of a “historical bloc” of a “national-popular” character. With the proletariat at the head, an alliance of the popular or subaltern classes (poor and middle peasants, progressive layers of the petty bourgeoisie, and, in a context such as Latin America, the indigenous peoples) had to be formed which, united by a popular progressive culture, (through a new philosophy and a new morality, new artistic and literary expressions, and a new spirituality that articulates the experiences of the people in a key revolutionary manner) could be transformed into a counter-hegemonic force, ready to contest the bourgeois common sense of society in a "war of positions", intervening politically and finally fracturing capitalist control of the means of production. A good recent example of how the consolidation of this popular hegemony can not only win the ideological dispute to the bourgeoisie, but also guarantee the vitality of a revolutionary process, is the recent victory of the MAS in Bolivia after the coup against Evo Morales in 2019. Despite the tragic political defeat, the forces of reaction could not finish imposing themselves on Bolivian society, since the profound changes in the national culture carried out by the MAS during its years in power, had earned it the massive support of a heterogeneous but ideologically favorable people for their political project. For this reason, eventually the coup plotters had no choice but to stop postponing the elections and accept their defeat and the return to power of their enemies. Of course, the coup against Morales also leaves the lesson that a victory in the war of positions does not guarantee the uninterrupted continuity of the revolution. It is also necessary to be prepared to win in the war of maneuvers, to defend by arms the transformation of society when the reactionaries make it necessary. However, it is clear that the thought of Antonio Gramsci, far from implying a break with Marxism-Leninism, represents a crucial, truly dialectical development of the materialist theory of history, one that is of great importance for thinking about the context of contemporary bourgeois democracies. AuthorSebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Translated and Republished from Instituto Marx-Engels.

2 Comments

Aaron Favila / AP WASHINGTON (PAI)—From coast to coast, demands for passage of the PRO Act, the most pro-worker labor law overhaul in 86 years, will take center stage at May Day marches, teach-ins, and events, preceded by other pro-PRO Act actions that began on April 26. The AFL-CIO reports more than 700 events are planned, and that count may be low, as individual unions check in with their own marches and meetings. And five big Bay Area labor councils joined together for a May Day march in San Francisco. Add to those events and marches one big town hall, on May 2, Confronting The Covid Economy: Women Fight Back, sponsored by People’s World and the International Labor Communications Association. Jobs With Justice Executive Director Erica Smiley, retired Coalition of Labor Union Women Executive Director Carol Rosenblatt, and Unite Here Local 1 shop steward Camilla Carrothers, and Phoenix, Ariz., organizer Haley Carrera will speak at the town hall. Arizona is vital for passing the PRO Act since its Democratic senators have yet to co-sponsor it. The forum will discuss “demands that can be made of lawmakers and others that will make the most difference in women’s real lives” and effective organization “to demand justice, equality, and an end to the exploitation and special oppression that particularly women of color face in the capitalist economy-in-crisis.” In the four days before that forum, April 28-May 1, Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor and the Labor Network for Sustainability will hold a virtual forum on issues intertwining worker rights and the green economy worldwide. Smiley and Service Employees President Mary Kay Henry, Teachers (AFT) President Randi Weingarten, and International Trades Union Congress General Secretary Sharan Burrows are among the speakers. Details are on the Kalmanovitz website. And the night of May Day, the DC Labor Film Fest will kick off with a discussion of a film, posted starting April 28, on Haymarket, The Bomb, The Anarchists, And Labor Struggle. Details are on the Metro D.C. Central Labor Council’s website. All of this ties into the struggle for workers’ rights—and passing the PRO Act is key. “Millions of Americans would join a union right now if they had the chance, but our outdated labor laws are preventing that from happening. The PRO Act is how we change that. It’s the next frontier for our workers,” David Driscoll-Knight, the AFL-CIO’s eastern regional director, said in a statement. The key point: To convince the balky U.S. Senate, tied 50-50 and under Democratic control only because of Vice President Kamala Harris’s tie-breaking vote, to both bring the legislation to the floor and to pass it. But it has to get there first, and there are still three Democratic holdouts: Both Arizona senators, Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly, plus Virginian Mark Warner. That led to daily demonstrations, even before May Day, with several dozen unionists at each, at the Tucson and Phoenix offices of Sinema and Kelly, along with a phone-a-thon to their offices from southern California colleagues. It also led to unionists parading to Warner’s offices in Tidewater, Va., through the week, something they plan to do on May Day as well in the D.C. suburb of Alexandria. Meanwhile, the Communications Workers hosted a three-day phone-a-thon for the PRO Act on April 26-28, with the Democratic Socialists joining them. The Sunrise Movement and other allies provided sample letters to e-mail senators. “The PRO Act is historic legislation that will put power in the hands of workers and reverse decades of legislation meant to crush unions. The bill will completely change labor law as we know it and shift power away from CEOs to workers,” says Our Revolution, organizers of the Alexandria event, in Windmill Hill Park. The PRO Act, organized labor’s top legislative cause, also has Democratic President Joe Biden’s vocal and strong support. It would make a variety of changes in U.S. labor law. Some are: Outlawing “right to work” laws, making union representation elections easier to hold, banning “captive audience” meetings, and legalizing card-check recognition if unions present election authorization cards from a workplace’s majority. The law would also fine labor law-breakers $50,000 per violation—or $100,000 for repeat offenders—rather than just net back pay for workers restored to jobs. There would be full disclosure of union-busters’ clients and spending and mandatory first-contract arbitration if the two sides can’t agree. And the National Labor Relations Board could more easily go to court for anti-union-busting orders. If it refused, workers and unions could sue on their own. The marchers won’t go into all these details. Instead, they’ll emphasize how the PRO Act will help workers economically and level the playing field against corporate greed, intimidation, and exploitation, especially of workers of color. That will be a top topic of an April 29 virtual forum hosted by the New York State AFL-CIO. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., who backs the PRO Act, will speak. But so will a top organizer from the recent Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union campaign to unionize Amazon’s 5,600-worker warehouse in Bessemer, Ala.—where the workforce is 80%, Black. The Bessemer worker will detail how Amazon’s illegal intimidation, captive audience meetings, pressure, and even anti-union diatribes in the plant’s bathrooms left RWDSU with the loss—and how the PRO Act would prevent all that. The union has filed a labor law-breaking complaint with the NLRB, which is investigating. It wants a rerun, minus company intimidation, but that ruling could take years. In some cases, the PRO Act isn’t the only cause of the May Day marchers. In many cities, including San Francisco, it’s intertwined with Workers Memorial Day, April 28—which has turned into Workers Memorial Week. In lower Manhattan, workers will take to the streets the morning of May Day around the headquarters of Conde Nast Publications, where company intransigence over even bargaining to a first contract has forced workers to consider a potential strike. “Condé Nast workers need our help!” their rally announcement says. “Members at The New Yorker, Pitchfork, and Ars Technica Unions voted overwhelmingly to authorize a strike, and the clock is ticking! Join us for a rally and picket on May Day to demand that Condé Nast and bosses throughout the media industry negotiate in good faith and treat workers fairly.” The St. Paul Union Advocate reports the May Day “Minneapolis march is being organized by a coalition of Twin Cities area unions, immigrant rights groups, and social justice organizations.” “The Facebook page publicizing the event says marchers will be calling for labor rights, justice for essential workers, immigrant rights, immigration reform, a halt to police brutality, and climate justice.” Union sponsors there include AFSCME Locals 2822, 3800, and 3937, the Augsburg Staff Union, Communications Workers Local 7250, SEIU Healthcare Minnesota, SEIU Local 26, and UNITE HERE Local 17. And in Los Angeles, a massive coalition of labor, community, and immigrant rights groups have joined together to organize a joint march, rally, and car caravan that will work its way through the city Saturday morning. AuthorMark Gruenberg is head of the Washington, D.C., bureau of People's World. He is also the editor of Press Associates Inc. (PAI), a union news service in Washington, D.C. that he has headed since 1999. Previously, he worked as Washington correspondent for the Ottaway News Service, as Port Jervis bureau chief for the Middletown, NY Times Herald Record, and as a researcher and writer for Congressional Quarterly. Mark obtained his BA in public policy from the University of Chicago and worked as the University of Chicago correspondent for the Chicago Daily News. This article was first published by People's World.

4/30/2021 Paris Commune at 150: Still Going Strong and Challenging Digital Capitalism. By: Dennis BroeRead NowWomen and men at the barricades in defense of the Paris Commune in 1871. | CC01.0, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons PARISHere in Paris, we are now living through the 150th anniversary of the Commune, identified by Karl Marx as perhaps the first worker’s republic established in the history of humanity. The commune lasted 71 days, beginning March 18, 1871, and ended in violent repression during what was called “the time of the cherries”—the budding of the cherry blossoms—in the bloody week of May 21 to 28. The commune was a response by the Parisians to the end of a war the emperor Louis-Napoleon had waged to distract the French from the corruption and negligence that characterized the latter stage of his Second Empire. The ill-fated war ended up uniting the German states under Bismarck as the French military, also hollowed out by years of corruption, was quickly defeated. The German army then became an occupying army and laid siege to Paris, figuring to starve the city into submission. The French ruling class, industrialists, and remnants of the old aristocracy, led by the emperor’s minister Adolphe Thiers, left the city and fled to the former palace of the king at Versailles, where they would soon collaborate with the Germans to crush the Commune. Inside the city, a new form of government appeared, direct democracy with elements of the national guard on its side and with the working people of the city behind it, and engaged directly in carrying out reforms in health, education, and establishing an equal status for women. Indeed, the face of the Commune that has come down through history is that of the feminist Louise Michel, in the forefront of many of these reforms and, upon the downfall of the Commune, was exiled from France. The Commune defied the industrialists and issued proclamation after proclamation that pushed the government of Paris toward a worker’s state. Thiers and the German collaborators he represented were furious and finally, with the aid of the German army, still encamped outside the city, moved to annihilate the rebellion, which he did in perhaps the bloodiest week of state terrorism in French history, other than the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of the Huguenots in 1572. Row after row of these working people were lined up and shot. The most sacred place commemorating the Commune is the Mur des Fédérés, the wall of these victims inside the famous cemetery Père Lachaise. With the Commune in ruins, its proponents either dead or exiled, Thiers then proclaimed the birth of the French Republic, ending forever the attempts to re-establish the monarchy after it had originally been overthrown in the French Revolution. Fall of the last vestiges of the monarchy. | Wikipedia, Public Domain Indeed, French Republicans now proclaim the Commune as a founding moment to establish a representative parliamentary democracy. However, that bourgeois democracy, with the industrialists now firmly back in power, was erected on the bones and coffins of the Parisian citizens who instead had instituted a direct democracy in which the people made decisions together. Battles over the memory of the Commune continue to be waged. Adolphe Thiers is commemorated in the traditional French manner by having streets and squares named after him in many French cities and towns. However, no street or square bears his name in Paris, the site of his bloody executions. The Catholic Church, attacked for its corruption by the Commune as it was in the French Revolution, allied with the state to anoint the Church of Sacre Coeur (Sacred Heart), which overlooks the city and stands as a symbol of the triumph of the bourgeoisie. However, just below the Church, in a way that suggests the old specter of revolution is not dead, sits Louise Michel square, with its commemoration of the Commune’s leading spirit. Released to coincide with the 150th anniversary is La semaine sanglante (The Bloody Week), a work by the French historian Michèle Audin which claims that Thiers’s accounting of the dead is vastly understated. The official figure is over 6,000 casualties, but by checking cemetery records, this new book claims the figure is at least 15,000 and may have been as high as 20,000, with underground mass graves of the Communards still being discovered in the 1920s in the building of a line of the Paris Métro. Mur des Fédérés – Monument aux victimes des Révolutions | Pascal Radigue, CC4.0, Wikimedia Commons France celebrated the March 18th date with great fanfare. Still, that celebration quickly gave way to its opposite as the country readies itself for the 200th anniversary in May of the death of Napoleon, a symbol of empire and conquest beloved by the right and no friend of democracy, whose nephew, founder of the second empire named in honor of his uncle’s self-proclaimed first empire, started the war that brought on the siege of Paris. Marx’s valuing of the experiment of the Commune, a spirit that is yet to be realized, points the way to why it remains at the same time a moment of hope for working people and a moment of fear for their new digital overlords, whether they be Jeff Bezos’s Amazon, Elon Musk’s Tesla, or Emmanuel Macron’s start-up nation: “The value of these great social experiments cannot be overrated. By deed instead of by argument, they have shown that production on a large scale and in accord with the behests of modern science, may be carried on without the existence of a class of masters; that to bear fruit, the means of labor need not be monopolized as a means of dominion over, and of extortion against, the laboring man [and woman]…; and that, like slave labor, like serf labor, hired labor is but a transitory and inferior form, destined to disappear before associated [fédérés or communal] labor plying its toil with a willing hand, a ready mind, and a joyous heart.” This website about the Mur des Fédérés has a host of information, resources, songs of the Commune, and photographs. AuthorDennis Broe’s latest book is Diary of a Digital Plague Year: Coronavirus, Serial TV and the Rise of the Streaming Services. He has taught at the Sorbonne and is currently teaching in the Master’s Program at the École Supérieure de Journalisme. He is an arts critic and correspondent for the British daily Morning Star and for Crime Time, People’s World and Culture Matters, where he is an associate editor. This article was first published by People's World.

El presente artículo terminó de escribirse el martes 27 de abril, en respuesta a la siguiente publicación de Jorge Frisancho: 'Sobre izquierdas reaccionarias y revolucionarias: una respuesta a Sebastián León' Read in English HERE Quiero agradecer a Jorge Frisancho por concederme el honor de responderme, a pesar de mi gesto arrogante y demagógico. Debo decir que yo defiendo mi gesto: creo que gracias a mis críticas ha tenido la oportunidad de explayarse y desarrollar algunas de las ideas que faltaba trabajar en su publicación original (si bien ignora de plano lo que para mí sería la objeción fundamental a su texto: su uso antojado y metodológicamente injustificado de sus redes sociales como si se tratara de una fuente confiable de data empírica). Dicho esto, puesto que Jorge me ha concedido esta cortesía, me veo obligado a corresponderle de la misma manera. Además, estoy de acuerdo con él en que de nuestro intercambio puede emerger un debate que hoy vale la pena tener en la izquierda. Así que, sin más preámbulos, paso a responder. Sobre el resentimiento y su relación con la conciencia de claseEl debate sobre el resentimiento, su relación con la conciencia de clase y con la política clasista puede extenderse excesivamente, y creo que en realidad no es lo más importante de mi discusión con Frisancho. Por ello trataré de no detenerme demasiado en este asunto e ir a las cuestiones más importantes. Empiezo diciendo que lo que Frisancho llama “ressentiment”, apelando como explica a cierta tradición de la sociología y la psicología, en realidad no es distinto de lo que en la tradición filosófica autores como Nietzsche y Spinoza llamaron “resentimiento”. Por ello, de saque, me permito no usar el término francés. De hecho, no hay un malentendido sobre el hecho de que él achaca a Perú libre una política, digamos, más de la performance de radicalidad a una política realmente radical o revolucionaria. Mi primer cuestionamiento a su texto, que a mi parecer es el más fundamental, es la cuestión metodológica: Frisancho se permite reducir los esfuerzos de una organización que hoy marcha a disputarle su existencia a la cara más rancia del neoliberalismo local a vísperas del bicentenario a lo que infiere a partir de su algoritmo de Facebook (reforzador de burbujas informativas y sesgos de confirmación). La cuestión no era si le gustaba o no Perú Libre o si le daba buena espina; era que, como teórico autoproclamado marxista, debía ser más responsable y riguroso en sus análisis. En su respuesta a mis críticas, Frisancho hace varias afirmaciones sobre el resentimiento y su relación con la conciencia de clase que, si debemos ser honestos, no podían inferirse de su texto original (enhorabuena por el desarrollo de sus ideas); en todo caso, estoy de acuerdo con algunas de ellas. No obstante, toca hacer algunas aclaraciones de rigor sobre aquello con lo que no estoy tan de acuerdo. La primera es que da igual si el texto de Frisancho se centraba exclusivamente en el resentimiento o en los afectos en general; mis críticas iban, fundamentalmente, a su tratamiento del resentimiento y la manera en que este se relaciona con el proceso de adquisición de conciencia de clase. Frisancho se felicita a sí mismo por haber empleado varias veces el término “conciencia de clase” en su artículo, pero la verdad es que en él no explica nunca dicho proceso. Quien lo hizo fui yo, aunque me haya “resistido” a nombrarlo. Lo segundo es que, si bien Frisancho considera que el resentimiento no es “ni bueno ni malo”, ni “racional ni irracional”, yo pienso que en cierto sentido sí va cargado de cierta racionalidad o irracionalidad. Esto porque, como expliqué, los afectos en los seres humanos no están nunca “dados” por sí solos, sino que se enmarcan en horizontes culturales de sentido. En una formación histórica determinada, habrá situaciones en las que un afecto como el resentimiento podrá considerarse justificado, o, digamos, habrá buenas razones para sentirse injuriado (aunque, y esto es fundamental, habrá que ubicar adecuadamente la causa). Esto no quiere decir, por supuesto, que el resentimiento sea bueno o malo en sí mismo; lo que quiere decir es que, en circunstancias determinadas, como cuando es producto de la afrenta histórica y sistemática, sentir resentimiento es razonable. Extrañamente, Frisancho piensa que se le señala como un “racionalista rancio” por no reconocer el lugar de los afectos y por “insistir” (nombrar varias veces) en la importancia de la conciencia de clase. Pero se equivoca: la razón por la que lo califiqué de tal manera es porque, como ya he mencionado, en su artículo original no explicó el proceso de mediación por el que se adquiere la conciencia de clase. Dice, ciertamente, que resentimiento y conciencia de clase son dos cosas diferentes, y distingue entre lo que para él hace una organización cegada por aquel afecto y lo que hace una organización dirigida por revolucionarios con conciencia de clase, pero no nos dice nunca cómo se pasa de uno a otra. De hecho, su respuesta a mis críticas todavía me genera algunas dudas sobre cómo entiende dicho proceso: dice que el argumento de su texto original puede resumirse en que el resentimiento “bloquea la conciencia de clase” (pese a que esto jamás se afirma en dicho texto), pero también dice que para ir más allá del resentimiento se necesita la mediación de la conciencia de clase. Esto no me resulta tan claro, y debo decir que la impresión que me da es que para Frisancho debe haber una intervención externa para sacar a los sujetos resentidos del atolladero. Al final, hay que decir que en el texto original sí que daba la impresión de que había una cesura entre el resentimiento y la conciencia de clase, y si bien en la respuesta a mis críticas insiste en que no hay interrupción entre procesos afectivos e intelectuales en su adquisición, sigue sin esclarecer de qué manera incorpora el resentimiento al desarrollo de la conciencia de clase conciencia de clase. Aquí hay una diferencia fundamental, me parece, entre mi postura y la de Frisancho: para mí el resentimiento (y afectos semejantes como la ira) justificado es una condición material necesaria (aunque no suficiente) para que pueda haber algo así como una conciencia de clase, y es la clase de narrativa histórica que Mariátegui llamaba “Mito” lo que puede dinamizar este y otros afectos y hacerlos políticamente operativos (es decir, para suscitar la ganancia en conciencia de clase). Otra cuestión importante, me parece, es que si bien Frisancho considera que en este punto él y yo estamos de acuerdo en lo fundamental (en que el resentimiento debe ser trascendido), no me queda otra opción que responderle: sí, pero no. Estamos de acuerdo en que el resentimiento por sí solo no es revolucionario, y que se hace necesaria una mediación dialéctica, pero yo no pienso que el resentimiento pueda literalmente ser superado o trascendido con la llegada de la conciencia de clase. Creo que esta le da una direccionalidad (digamos, lo modifica o lo “refina”), que es distinto; sin embargo, como yo lo entiendo, el resentimiento y otros afectos negativos presentes en la política clasista solo pueden terminar de superarse con la abolición de las condiciones históricas que lo producen (momento en el que desaparecen, junto con las relaciones de clase y la conciencia de clase como tal). Por eso digo que “el resentimiento y demás afectos corrosivos pueden ser sublimados en el proceso en el que surge un nuevo orden social a partir del viejo”. El resentimiento de una clase históricamente oprimida, con conciencia de su situación, solo desaparece con el surgimiento del comunismo[1]. Sobre la cuestión de la verdadera izquierda Ahora llegamos a la parte realmente importante de nuestro intercambio: la cuestión de “qué hace revolucionaria a una organización”. Frisancho da su propia definición, y debo decir que yo no podría haberlo expresado mejor. Paso a citarlo: Una organización política es revolucionaria en la medida en que lucha, en última instancia y a partir de la conciencia de clase de las clases trabajadoras, para derogar la totalidad del orden social e instaurar uno nuevo. Obviamente, esta definición es teórica y solo sirve como orientación general; las situaciones, coyunturas y experiencias concretas son las que dan forma práctica a las cosas, y la separación entre ambos planos es útil únicamente como ejercicio de análisis. Ningún conjunto de ideas políticas tiene contenido independiente de la praxis. Además, las demandas tácticas y estratégicas obligan, necesariamente, a decidir qué confrontaciones se enfatiza y qué pasos se da para ir avanzando en cada momento determinado. Esa es la función del liderazgo, o una de ellas. Pero pongo el asunto en ese terreno porque me permite señalar el problema al que apunto, que en mi artículo expresé como la existencia de una “izquierda reaccionaria”. Aquí Frisancho añade, básicamente, que una organización que se declare marxista que no trabaje para derogar todas aquellas las relaciones sociales (“instituciones, aparatos y prácticas”) que producen situaciones de opresión (de clase, de género, de los miembros de la comunidad LGTBIQ+) es reaccionaria, pues todas estas luchas son expresión de las formas de coerción específicas del orden social burgués. Está haciendo una clara alusión a Perú Libre, y es una manera de reafirmarse en su posición de que se trata de una organización de izquierda que puede ser calificada merecidamente como “reaccionaria”. En este punto surgen una vez más mis discrepancias con Frisancho. No porque discrepe con que la cuestión de género o la lucha por los derechos de las personas LGTBIQ+ son luchas tan fundamentales como las de los obreros, los campesinos o los pueblos indígenas (de hecho, concebirlas de manera separada es siempre una abstracción, pues, por ejemplo, quien pertenece a una clase social siempre tiene además un género y una orientación sexual), o que respondan a contradicciones específicas de la totalidad social capitalista (y que por tanto no pueden ser desestimadas como “luchas burguesas”). Sino porque yo no pienso que se pueda afirmar tan tranquilamente que si una organización socialista y marxista no está comprometida con todas las formas de opresión desde el comienzo esta deba ser descartada como reaccionaria, como si el carácter revolucionario apareciera solo en el momento en el que se marcan todos los ítems en una lista; eso está muy bien para el mundo de las izquierdas y los movimientos sociales ideales, pero la política se hace en el mundo real, con organizaciones políticas y movimientos sociales reales. ¿Hay elementos reaccionarios en una organización como Perú Libre, que descuida las luchas de las poblaciones LGTBIQ+? Por supuesto que los hay; pero, ¿se puede decir realmente que esto hace de Perú Libre una organización de izquierda reaccionaria? Pero lo que más me llama la atención es que Frisancho ponga la valla tan alta para Perú Libre, pero la baje convenientemente para la organización que apoyó en la primera vuelta (Juntos por el Perú). Porque bajo el mismo criterio que utiliza Frisancho, podríamos decir sin problemas que Juntos por el Perú también sería una izquierda reaccionaria: una izquierda que aunque se reclame representante de los intereses de las clases populares, dedicó casi por entero su táctica electoral a ganarse a las clases medias y en desmedro de obreros, campesinos e indígenas (realidad que se veía reflejada en las encuestas que mostraban en qué sectores de la población se encontraban sus votantes, que se hizo explícita con el desafortunado audio de Marité Bustamente, y que terminó de confirmarse con los resultados de las elecciones); o que una y otra vez pisoteó en su discurso la solidaridad antiimperialista y anticolonial, plegándose a las exigencias de la derecha de denunciar procesos como el venezolano por dictatoriales, reproduciendo la narrativa imperial sobre una comunidad internacional dividida en “dictaduras” y “democracias”, que legitima atrocidades como los ínfames bloqueos económicos, que no son otra cosa que formas contemporáneas de asedio. Si ninguna de estas luchas es más fundamental que otra ni puede ser desestimada en las coordenadas del capitalismo contemporáneo, hay que decir, pues, que JPP está, al menos, tan lejos del estándar ideal de Frisancho como PL (aunque me inclino a pensar que mi interlocutor podría no dar demasiada importancia a una lucha como la que se da en el campo internacional; me explayaré sobre ello en la parte final de mi artículo). Creo que es importante añadir, asimismo, que si bien PL tiene un serio déficit en lo que respecta a la consideración de las luchas LGTBIQ+, no es cierto que lo tenga también en la cuestión de género; quien haya leído el “Programa e Ideario” de la organización podrá comprobar que este contiene un capítulo entero dedicado a “La mujer socialista”, elaborado por las militantes de la organización, en el que se posicionan a favor de la emancipación de la mujer, se asumen reivindicaciones históricas como el aborto y se denuncia el machismo como un mal estructural del capitalismo y el colonialismo (de hecho, candidatas al congreso como Zaira Arias y Angélica Apolinario fueron vocales sobre estos temas durante sus campañas)[2]. Así que hay decir, en honor a la verdad, que al contrastar el número de casillas marcadas en la lista de ítems de ambas organizaciones saldría favorecido Perú Libre (por supuesto, yo no comparto este criterio idealista para designar a una organización como revolucionaria o reaccionaria). Aquí quisiera hablar un poco desde mi experiencia como militante de izquierda. En la coyuntura del 2017 en la que muchos conocimos a Pedro Castillo, cuando el magisterio rompió con el PCP-Patria Roja para ir marchar a Lima a hacer valer sus reclamos, muchas organizaciones de izquierda y sindicatos de trabajadores decidimos apoyarlos; entre dichas organizaciones estaba presente Perú Libre, pero la bancada de Nuevo Perú (que junto a PR conforma JPP) decidió no recibir a los maestros para no mancharse, debido al terruqueo del que estos fueron víctimas. Ese mismo año, en diciembre, en la coyuntura de la vacancia presidencial contra PPK, una vez más un sector importante de la izquierda (que también incluía a PL) nos posicionamos a favor de la vacancia y formamos parte del Frente Popular Anticorrupción por una Nueva Constitución, y luego del Comando Nacional Unitario de Lucha; fue en ese tiempo que nació la consigna “que se vayan todos”, que denunciaba el orden institucional neoliberal en su totalidad, pero la bancada del NP prefirió defender a PPK y la institucionalidad democrática (finalmente se plegarían a la causa, después de que PPK decidió indultar a Alberto Fujimori para permanecer en el cargo). A finales del 2018, ya con Vizcarra en el poder, este promulgó el Decreto Supremo N° 237-2019-EF, por el que entraba en vigencia el Plan Nacional de Competitividad y Productividad (probablemente el paquetazo antilaboral más violento que haya habido desde los tiempos del fujimorato; la infame “Suspensión perfecta de labores”, que en el contexto de esta pandemia ha costado a tantos peruanos su empleo, formaba parte del PNCP); en lugar de ir a las calles con la clase trabajadora en dicha coyuntura, el MNP privilegió secundar a Vizcarra en su pantomima de lucha anticorrupción, siendo los principales defensores de una reforma política puramente cosmética, secundando, una vez más, al gobierno de turno. ¿Por qué menciono todo esto? Porque en los últimos años, con todos sus errores y limitaciones, PL, a diferencia del NP, ha sido una organización a la que siempre he encontrado al lado de la gente en sus luchas (por supuesto, no pretendo argüir que mi experiencia personal sea la mejor fuente de evidencia para establecer un juicio objetivo, pero estoy convencido de que es largamente más fiable que mi algoritmo de Facebook[3]). Las críticas a JPP y las organizaciones que la componen, que tanto parecen molestar a Frisancho y a otros simpatizantes de dicha coalición, pueden no ser del todo justas; no obstante, considero que tienen algo de sustento[4]. A riesgo de que Frisancho nos acuse de espontaneistas que andamos tras las masas aceptando acríticamente todos sus posicionamientos inmediatos para sentirnos radicales, hay que decir que PL ha sido coherente con la idea que revolucionarios como Lenin o Mao tenían del papel de una vanguardia: ni se ha contentado con acomodarse a la espontaneidad de los distintos sectores del pueblo, ni ha pretendido imponerse como una élite tutelar a la usanza del progresismo más cortesano. Ha sabido entablar un diálogo con ellas, agitar, educar y organizar. Esto no quiere decir que la gente (o la organización) tenga razón en todo, pero hay una correcta comprensión de que el proceso revolucionario nace desde abajo, y que la labor de la organización socialista en dicho proceso (que es siempre un proceso de acumulación de experiencia mediante la lucha) es acompañar y orientar a las masas, ayudarlas a ganar claridad sobre sí misma y sobre sus luchas[5]. Tampoco quiere decir, como podría temer Frisancho, que, si un sector mayoritario de la gente no ve con buenos ojos la defensa de ciertas causas, estas deban ser abandonadas; más bien, quiere decir que no se trata de descartar a priori a ningún grupo oprimido como reaccionario in toto, sino de dirigirse a este como un interlocutor válido, con el que se puede dialogar y razonar, y que puede aprender de la vanguardia en la misma medida en que es capaz de educarla. Es esta la manera en que se superan las contradicciones en el seno del pueblo, y, hay que decirlo, es también la manera en que se gana su confianza. No hay evidencia más clara de ello que el apoyo popular que terminó recibiendo PL en contraste a JPP durante la primera vuelta; de hecho, quienes seguimos la campaña de Pedro Castillo desde el principio, sabemos que, a partir de cierto momento, las propias bases regionales de JPP comenzaron a reconocer a Castillo como su candidato, y lo recibían codo a codo con las bases de PL. Sería importante que los simpatizantes de la organización de Mendoza comiencen a reflexionar sobre esta derrota táctica. El trabajo de bases metódico por parte de PL y Pedro Castillo también es importante por otras razones de índole pragmática: sumado a su coherencia en el discurso en lo que respecta a la voluntad de sacar adelante una Asamblea Popular Constituyente (causa que me consta personalmente que vienen defendiendo desde hace años) y de desmantelar el modelo neoliberal (fuerte contraste con un JPP y una Mendoza altamente inconsistentes, propensos a desdecirse según los vaivenes de la campaña, y que en determinado punto incluso llegaron a alabar el programa Reactiva Perú, por el que Vizcarra y la ex-Ministra Alba pusieron 60 mil millones de soles en manos del gran empresariado peruano), el apoyo de las masas obreras, de las rondas campesinas, del magisterio y de organizaciones indígenas, daba al partido una fuerza material real, la posibilidad de llegar al poder con un contrapeso que pudiera mantener a raya los esfuerzos del empresariado por coaptarlos. Aunque a Frisancho y otros simpatizantes de JPP les sorprenda, esta credibilidad incluso ganó a Castillo y PL votantes entre los sectores populares y más radicalizados del feminismo limeño y de la comunidad LGTBIQ+. Como manifestaron varios de mis compañeros durante esta primera vuelta: lo que sectores más privilegiados de estos colectivos muchas veces no llegan a comprender es que entre una izquierda comprometida con derechos individuales pero indispuesta a atacar el modelo económico que nos impide disfrutar de dichos derechos, y otra que no asume dichos compromisos pero que manifiesta de manera creíble la voluntad de reemplazar dicho modelo por otro que eventualmente permita disfrutar de esos derechos, hay quienes creerían que desde un punto de vista táctico la segunda es una mejor opción. Al final del día, el progresismo no se mide de manera absoluta por cuántas consignas uno levante; más bien, es siempre relativo a la correlación de fuerzas y las luchas de clases[6] en un momento histórico determinado. Por eso, entre un MHOL que actualmente afirma que es igual de bueno para el colectivo LGTBIQ+ votar por la activista Gahela Cari que por un ultraderechista como Alejandro Cavero, y una organización socialista que, sin levantar la bandera LGTBIQ+, hoy tiene la posibilidad de crear condiciones para que jóvenes homosexuales o trans que no tienen estabilidad laboral, la posibilidad de acceder a educación o servicios de salud básicos, a un seguro y/o a una pensión (condiciones materiales necesarias para independizarse de entornos abusivos y para disfrutar en el futuro del derecho a crear una familia junto a sus personas amadas), me inclino a pensar que, en el presente, lo segundo es más cercano a una fuerza progresista. Y, por tanto, más cercano al ideal revolucionario propuesto por Frisancho. Pedro Castillo -Peru Libre. Respuesta a la nota final:¿marxismo-leninismo o socialdemocracia?Frisancho cierra su respuesta a mis críticas extrañado por mi referencia al debate entre comunistas y socialdemócratas en la Segunda Internacional. Él, comenta, no está tan seguro como yo de que la historia haya favorecido a los comunistas (al leninismo) en ese debate; según nos dice, él considera que al final ninguna de las dos tenía razón, y que ambas experiencias habrían tenido tanto aciertos como desaciertos (esto último innegable, por supuesto). Esto debido a que, pese a la grandeza que Frisancho reconoce a Lenin como figura seminal del marxismo, la URSS habría dejado de existir, como consecuencia “tanto a la tenacidad y potencia de sus enemigos como sus propias falencias internas, y si de lo que se trata es de construir un socialismo que perdure, que consiga oponerse de forma efectiva a la dictadura de las clases capitalistas y que emancipe a los trabajadores, no parece que lo más recomendable sea levantar como bandera una apuesta que terminó en derrota.” Debo confesar que la idea general de esta respuesta (el que a juicio de Frisancho, entre el leninismo y la socialdemocracia, ninguna de las dos tuvo razón) no me sorprende en absoluto. Me sorprende más que Frisancho use como argumento para defender su postura la caída de la URSS. Creo que el debate entre comunistas y socialdemócratas es vigente porque se centra en una problemática que sigue siendo fundamental, y que, a mi juicio, Frisancho y el sector de la izquierda por la que se inclinó en la primera vuelta electoral descuidan en exceso (de hecho, a mi juicio, y ciñéndome sus criterios, es aquí donde se ve el lado más reaccionario de sus posicionamientos). La razón fundamental del desacuerdo entre comunistas y socialdemócratas fue la problemática del imperialismo y la colonialidad: mientras que los socialdemócratas de la Segunda Internacional consideraban que el socialismo era algo que no competía a los países atrasados de la periferia global, donde prevalecían formaciones socioeconómicas agrarias y las masas eran mayoritariamente campesinos “reaccionarios” (muchos socialdemócratas, como Bernstein, llegaron a favorecer el ideal de un tutelaje de la metrópoli capitalista europea sobre las colonias, que por un lado permitiría mejorar las condiciones de vida de los obreros europeos, y por el otro ayudaría a desarrollar el capitalismo en los países atrasados), los comunistas consideraban, más en línea con las ideas de Marx y Engels, que lo que competía al movimiento obrero internacional era solidarizarse con las luchas nacionales de los países periféricos, ayudarlos independizarse y hacer valer su soberanía nacional (política y económica) frente a Europa, debilitando en el proceso al capitalismo occidental y, a la larga, ganando mayor libertad e igualdad para los pueblos coloniales en las coordenadas globales del capitalismo. Esta fue la bandera del leninismo desde el principio, y pese a todos los problemas y desaciertos que menciona Frisancho, la levantaron una y otra vez durante la historia del siglo XX (en China, en Corea, en Cuba, en Vietnam, en Argelia, en Angola, en Palestina, en Sudáfrica, en Burkina-Faso, etc.); aunque hoy muchos lo olviden y se inclinen por señalar la caída de la URSS como evidencia del fracaso del marxismo-leninismo, la verdad es que este posicionamiento de los comunistas cambió la cara de la correlación de fuerzas internacional, en especial en Asia y África, donde muchas veces las poblaciones nativas estaban excluidas del derecho burgués que tantos marxistas occidentales vilipendian y dan por sentado. De hecho, este papel de la URSS y el comunismo internacional, como muchos han reconocido, influyó enormemente, para bien, en la lucha por los derechos civiles y la conformación de los Estados de bienestar en occidente: en lugares como EEUU, fue el apoyo de los comunistas a poblaciones oprimidas como la afroestadounidense, el movimiento feminista, los migrantes hispanoamericanos o los pueblos indígenas, sumado al gran temor de las autoridades de que estas (o los trabajadores) pudieran radicalizarse, lo que llevó al gobierno a reconocerles progresivamente una serie de derechos fundamentales. El temor de los países europeos al avance de los comunistas permitió a los socialdemócratas llegar al gobierno y poner en práctica sus políticas reformistas, vistas por las clases dominantes como un recurso desesperado para proteger la propiedad privada; y hay que resaltar que, aunque Frisancho lo ignore, muchas de las políticas de bienestar de estos gobiernos progresistas solo pudieron sostenerse gracias a las políticas predatoriales que estos mismos países llevaron a cabo en el Tercer Mundo. Es por esto que me permito señalar confiadamente que, entre los comunistas y los socialdemócratas, serían los primeros los que fueron favorecidos por la historia (es decir, quienes tuvieron más aciertos, quienes más hicieron para mejorar las condiciones de vida de las poblaciones oprimidas alrededor del mundo y más tienen que enseñar a una organización de izquierda revolucionaria contemporánea)[7]. Por supuesto, entiendo que Frisancho no comparta este punto de vista, pues veo que la solidaridad antiimperialista (aunque pueda decir que la defienda en abstracto) no es un tema al que le dé demasiada importancia; de ahí que no solo minimice el descuido de JPP en estos temas, sino que además se permita cuestionar las credenciales socialistas de organizaciones y países que establezcan alianzas con figuras que a él le resultan cuestionables (como el presidente ruso Vladimir Putin, a quien en su momento le dedicara un artículo). Frisancho, después de todo, no parece tomar muy en serio el compromiso leninista de la no intervención o el derecho de la soberanía de los países periféricos, el hecho de que, nos guste o no el gobierno de un determinado país, los únicos que pueden cambiarlo (o derrocarlo) son sus ciudadanos, y que los países y organizaciones que defienden este derecho de cada pueblo a la soberanía en la arena internacional deben hacer una causa común para resistir los embates del imperialismo de EEUU y occidente; tampoco el hecho de que un país o una organización política y económicamente aislada, que se toma la libertad de aliarse solo con aquellos con quienes mantiene plena coincidencia ideológica, está de antemano condenada al fracaso. Pues figuras como Putin pueden parecernos cuestionables o hasta reaccionarias en las coordenadas nacionales de sus respectivos países, pero lo cierto es que, sin su apoyo económico, político y militar (o el de países comunistas como China o Vietnam), países como Cuba, Venezuela o Siria hace tiempo se habrían convertido en nuevas Libias (a diez años después de la intervención de la OTAN, el países africano sigue completamente devastado, con tres fuerzas políticas diferentes disputándose el gobierno). Al final, vuelvo a insistir en ello, las fuerzas políticas progresistas y revolucionarias se construyen a partir de las condiciones materiales realmente existentes. Y aunque la realidad raras veces coincide plenamente con nuestros criterios ideales, resulta políticamente inoperante denunciarla por sus impurezas. Notas [1] Una última aclaración sobre este punto, de carácter conceptual y no tan importante para nuestra discusión, pero que no quería dejar de tocar en este artículo. En su respuesta, Frisancho hace otra afirmación que me resulta extraña: dice que hay que entender, cuando se habla de conciencia de clase, que “conciencia no es razón”. Su afirmación me resulta extraña porque, si uno tiene presente la discusión filosófica sobre la subjetividad, la conciencia y la razón que históricamente precedió a Marx, y que es parte de su herencia teórica, es claro que “conciencia de clase” debe ser entendido como razón, y no como mera conciencia. Paso a explicarme brevemente: la conciencia de clase es conciencia de sí (o, mejor dicho, “para sí”), en tanto sujeto que pertenece a una clase social (la clase deja de ser “clase en sí”, una mera facticidad empírica, y pasa a ser “clase para sí”: es decir, pasa a ser consciente de sí misma de manera reflexiva, de sus propias condiciones materiales de existencia, de sus intereses, y de su conciencia de sí misma, de su actividad consciente, en tanto clase social). Así pues, si debemos ser precisos, la conciencia de clase no es una mera conciencia pasiva (como la que tiene un animal que se percibe a sí mismo y a su entorno), sino lo que los idealistas alemanes llamaban una “autoconciencia”, que emerge necesariamente como parte de un proceso social e histórico de autodescubrimiento, siempre en relaciones con otros seres autoconscientes y con un trasfondo histórico determinado en el que se hace posible comprender, de manera progresiva, las implicancias o el sentido de las acciones, pensamientos, afectos, etc., propios y ajenos. La palabra más común que se ha usado para hablar de esta forma de autoconciencia es, precisamente, “razón” (Vernunft)[1]. Afirmar que la conciencia de clase es mera conciencia y no razón implicaría, desde un punto de vista filosófico, un retroceso hacia un paradigma cartesiano y psicologista de la conciencia, irreconciliable con una teoría materialista de la historia. Hago esta aclaración en un pie de página para no hastiar a nuestros lectores con disquisiciones demasiado abstractas. [2] A muchas personas en la órbita de JPP les ha sabido mal que en el mismo capítulo se critique el feminismo como contraparte del machismo, pero hay que entender que fuera de círculos activistas y académicos, hay organizaciones y movimientos de mujeres que enarbolan el estandarte de la emancipación de la mujer sin reconocerse a sí mismas como feministas, y defendiendo intereses que, si bien convergen en algunos puntos con el del feminismo exportado de occidente, se diferencian de este en varios otros, por el sencillo hecho de que en varios aspectos las condiciones de vida de una mujer obrera o una rondera son diferentes que las de una activista o una académica de clase media. Creo que más allá de que se rechace el término (por asociarlo a un feminismo exportado de la realidad occidental) o del machismo rampante de algunos militantes (que, por cierto, aunque a algunos les parezca, no es un mal que aqueje exclusivamente en Perú Libre), habría que entender que sencillamente se defiende feminismos diferentes. [3] Y ya que hablamos de mi algoritmo de Facebook, alguien debería comentarle a Frisancho que así como en sus redes sociales él se encontró con despliegues de chovinismo por parte de los simpatizantes de Perú Libre, otros nos encontramos con despliegues semejantes por parte de los simpatizantes de Nuevo Perú: desde persistentes mensajes ninguneando la opción por Castillo y airadas exigencias de que se renunciara a su candidatura, hasta acusaciones de traición, racismo rampante, terruqueo, burlas por no ser tenidos en cuenta por el resto de la izquierda latinoamericana, y una repetición acrítica de la versión de la derecha sobre la sentencia a Vladimir Cerrón (quien no tiene que gustarle personalmente a nadie, pero cuya sentencia ha sido desestimada incluso por personajes externos a la izquierda, como el periodista Ricardo Uceda, como un caso más del lawfare al que los dirigentes de la izquierda regional, desde Gregorio Santos a Walter Aduviri pasando por el propio Cerrón, son sometidos en nuestro país). La lista sigue, pero creo que mi punto se deja entender. [4] Esto incluye la acusación de “oenegera”, que no debe ser desestimada sin más como una manifestación de resentimiento; es bien sabido que ONG’s estadounidenses como USAID, la NED o HRW, financiadas por el departamento de Estado estadounidense, mantienen vínculos con numerosos personajes que son o han sido parte de JPP. Le guste o no a Frisancho, tales organizaciones tienen una agenda en nuestro país que suele coincidir con la de su embajada, y es por eso que líderes de izquierda como Evo Morales las han expulsado de sus países. Tampoco se trata de mera conspiranoia; es reconocer, más bien, el simple hecho de que la lucha por la emancipación se da también en el campo internacional y que el enemigo es rico en recursos. [5] Fue el joven Marx quien, en una carta a Arnold Ruge, hizo valer primero esta consigna de las organizaciones revolucionarias que se convirtiera en principio fundamental del leninismo: [6] Hablo en plural porque no creo que las luchas de clases puedan ser reducidas exclusivamente a la problemática de la producción, a la explotación de los obreros o los campesinos. Pienso, por ejemplo, que la problemática de género y de los derechos reproductivos de la mujer es una problemática de clase, en la medida en que el género ata a un sector mayoritario de las mujeres a una relación de explotación y dependencia económica y moral frente a sus pares varones (Engels mismo habla de la opresión de las mujeres como la primera opresión de clase); asimismo, pienso que la problemática (neo)colonial en el plano internacional debe abordarse de manera semejante. [7] Todo esto sin mencionar la modernización de países como los de la ex-URSS, China y Vietnam en términos de infraestructura, transportes, ciencia y tecnología, educación, etc., todos dirigidos por partidos marxistas-leninistas, que a la larga han redundado en mejoras sustanciales en la calidad de vida de millones de personas. No me parece una cuestión menor. AuthorSebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. 4/27/2021 Today, Defense of the Revolution Rests with the Media. By: Steve Lalla & Saheli ChowdhuryRead NowVeteran combatant of Cuba’s revolutionary struggles, Comandante Víctor Dreke, in 2017. Photo: Le Soir/Dominique Duchesnes. Víctor Dreke, legendary commander of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, called for those defending the Revolution today to recognize that the battlefield of the 21st century is the media. The comments were made at a conference held on Thursday, April 22, commemorating the 60-year anniversary of the Bay of Pigs—Playa Girón to the Spanish-speaking world. Comandante Dreke, now retired at age 84, spoke alongside author, historian, and journalist Tariq Ali; Cuba’s Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Bárbara Montalvo Álvarez; and National Secretary of Great Britain’s Cuba Solidarity Campaign, Bernard Regan. “It is no longer about us, the over-80s,” said Dreke. “It is the next generation, those who are here, who are going to be even better than us. It will no longer be a case of combat… Right now, the media across the world has to defend the Cuban Revolution, and we and you have to be capable of accessing the media across the world to spread the truth about the Cuban Revolution. That is the battle we are waging today—to fight attempts to weaken the people, to soften the people, to try to take the country again. They have changed their tactics. We are ready, but we want to say to our friends in the Americas and around the world that Cuba, the Cuba of Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, Juan Almeida, the Cuba of Che Guevara, will never fail, neither with us nor with the future generations.” Dreke joined the 26 July Movement in 1954, fought under Che Guevara in the Cuban Revolutionary War and in Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1965, and commanded two companies in Cuba’s historic defeat of US imperialism at the Bay of Pigs. Dreke’s autobiography, From the Escambray to the Congo: In the Whirlwind of the Cuban Revolution, was published in 2002. Cuba and Venezuela provide inspiration for Latin America and the worldComandante Víctor Dreke drew a comparison between Cuba’s historic defense of the revolution and that of Venezuela, as both countries now face a common weapon in the arsenal of imperialism: the economic blockade. “They block medicines for Cuba, they block aid for Cuba,” said Dreke. “They blockade the disposition of aid for Venezuela because of the principles of Venezuela, the principles of Chávez, the principles of Maduro, the principles of Díaz-Canel, the principles of this people, due to the historical continuity of this people.” Regarding the failed 1961 US invasion of Cuba, Dreke remarked, “it was an example for Latin America that proved that the US was not invincible; that the US could be defeated with the morality and dignity of the people—because we did not have the weapons at that time that we later acquired. It had a meaning for Cuba, the Americas, and the dignified peoples of Latin America and around the world.” Tariq Ali: we must see through ideological fabrications to defeat imperialismTariq Ali, esteemed author of more than 40 books, recalled the precursor of the US invasion of Cuba, the 1954 CIA coup in Guatemala in which President Jacobo Árbenz was overthrown and forced into exile. A young Ernesto Guevara was living in Guatemala at that time and bore witness to the multifaceted CIA operation PBSuccess, which included bombing campaigns with unmarked aircraft and a propaganda blitz of leaflets and radio broadcasts. Ali described the evolution of CIA tactics since then: “Normally the way they choose is to occupy a tiny bit of territory, find a puppet president, and recognize the puppet president. They are doing that in the Arab world today, or have been trying to do it. They did it with Guaidó in Venezuela, except that the Venezuelan army would not play that game and it blew up in their face, their attempt to topple the Maduro regime. They are trying it in parts of Africa. The weaponry has changed, it is more sophisticated, but the actual method they use, ideologically, is the same. That’s why it always amazes me as to why so many people believe the rubbish they read when a war is taking place.” Ali also weighed in with a forecast for US foreign policy under the Biden administration: “We can be hopeful for surprises… But effectively, whoever becomes president of the United States, whether it is Obama, or Biden, or Trump, or Clinton, or Bush, they are presidents of an imperial country, an imperial state, and this imperial state is not run all the time by the Congress or the Senate or the Supreme Court. The military plays a very important role in the institutions of the state, and the National Security Council, the Pentagon, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the Central Intelligence Agency are in and out of the White House, so the president who decides to make a sharp shift—it can be done, I am not saying it cannot be done—would have to be very brave and courageous indeed.” “Whoever from the Democrats gets elected—whatever their position—immediately comes under very heavy pressure,” Ali elaborated. “If you look at AOC [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez]… initially very radical, but now she is totally on board… I have never heard her say sanctions should be lifted, and she certainly supports even the old Trump line on Venezuela.” Hybrid warfare in the information age“Direct warfare in the past may have been marked by bombers and tanks, but if the pattern that the US has presently applied in Syria and Ukraine is any indication, then indirect warfare in the future will be marked by ‘protesters’ and insurgents,” detailed Andrew Korybko in the publication Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change. “Fifth columns will be formed less by secret agents and covert saboteurs and more by non-state actors that publicly behave as civilians. Social media and similar technologies will come to replace precision-guided munitions as the ‘surgical strike’ capability of the aggressive party, and chat rooms and Facebook pages will become the new ‘militants’ den.’ Instead of directly confronting the targets on their home turf, proxy conflicts will be waged in their near vicinity in order to destabilize their periphery. Traditional occupations may give way to coups and indirect regime-change operations that are more cost effective and less politically sensitive.” Hybrid warfare, waged today by the US and its political allies in conjunction with transnational corporations that wield powerful influence over mass media and political institutions, comprises the fields of economic warfare, lawfare, conventional armed warfare, and the information war. This last and most important—according to Commander Dreke—element in turn includes the manipulation of the press to serve capitalist and imperialist interests, the manufacture of fake news stories out of whole cloth, and targeted attacks on individuals, parties, or peoples who speak out against the failings of the present order. Moreover, hybrid warfare extends to interference in the political field and in electoral processes, the mounting of media campaigns to drive public attention into particular channels, and myriad assaults on our consciousness that attempt to turn us against each other, prevent us from seeing our common interests, and confuse us as we try to overcome defeatism and work to build a better world. Author Steve Lalla is a journalist, researcher and analyst. His areas of interest include geopolitics, history, and current affairs. He has contributed to Counterpunch, Monthly Review, ANTICONQUISTA, Hampton Institute, Resumen LatinoAmericano English, Orinoco Tribune, and others. Originally published by Orinoco Tribune