|

3/31/2021 Biden's National Security Guidance Document Reflects The Old Imperialist Foreign Policy. By: Alvaro RodriguezRead NowSecretary of State Antony Blinken has indicated that when it comes to China and Russia he favors continuing the failed policies of confrontation with rather than cooperation with those countries. | Carolyn Kaster/AP There was hope that after the world-wide pandemic, mutual cooperation and sharing would be the new normal among all the countries affected by the pandemic. And we have seen a few hopeful signs in this regard but there are serious concerns now that we may not see real international cooperation become the norm. If we look at the Interim National Security Guidance document put out by the Biden Administration recently the indications are that in foreign policy, we are getting from this administration the same old U.S. imperialism and it will take a massive mobilization to turn that around. While Trump’s slogan was “America First,” the Biden foreign policy might be characterized as “America is back.” There is a difference in tone but the foreign policy path the country is on is essentially the same. Throughout the document, you see the word “strength” repeated constantly, 36 times. There are belligerent statements such as, “The United States will never hesitate to use force when required to defend our vital national interests.” This document, even as it says it prefers to ditch confrontation, intends to continue a policy of strangling China’s technological advancement through “vigorous competition” which the administration has already shown involves lining up countries to help the US weaken China economically. So far there is no rejection of the continued hot wars in the Middle East. Biden calls Russia’s leader, Putin, a “killer” and threatens new sanctions against Russia, while only scolding “Bone-Saw Murderer” Mohamed bin Salman. MBS, as he is called, is the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, identified by Biden himself as authorizing the killing and dismemberment of Jamal Khashoggi at a Saudi consulate. Khashoggi was a columnist for the Washington Post and a permanent resident of the United States. Biden refuses to call MBS a killer. Why the belligerency?The aim of U.S. imperialism is to make the world safe for U.S. finance corporations to maximize their ill-gained profits. Other aims include setting international rules suitable to U.S. extreme right class economic and military interests, keeping the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency, protecting death merchants defending the fossil fuel industry, and defending the chemical/pharma industry’s assault on the health of the planet and our international working class. These predatory aims require the invention of enemies. In the past, these used to be the Soviet Union and later, global terrorism. Now it is China, Russia, North Korea, Venezuela, Iran, and other countries trying to exercise their independence and their right to develop and choose their own economic paths. This “national security” guidance document shows clearly who the main target will be – China. China is attacked at least 14 times. Russia is attacked five times. They are labeled as “biggest threats” and “antagonistic authoritarian powers.” If we are to successfully achieve a world where everyone is cooperating to solve the problems of the planet these countries should be seen as partners rather than threats. They are seen as threats because the U.S. security establishment sees them as an impediment to U.S. imperialism. As such these countries are described as enemies of “democracy” while the U.S. is held up as the epitome of democracy. The reality is that the world is becoming more multilateral and U.S. imperialism is on the decline. That makes U.S. imperialism more dangerous. When the word “democracy” is mentioned, it is a code word for capitalism and imperialism. The U.S. intends to revitalize the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Indo-Pacific “Quad” Alliance – Japan, India, Australia, and the U.S., thus attempting to “contain” the rise of China and Russia. In this document, Biden tries to connect the problematic foreign policy to the issue of “making life better for working families.” It is merely a cover for the promotion of imperialist policies, at odds with the true interests of the working class. Can we really have a progressive policy at home and an imperialist policy abroad? The answer is obvious. This is, in the long run, an impossibility. In the document, Biden pretends to modernize the national security institutions while making life better for working families. It is the same old rhetorical argument made under Reagan, “Guns or Butter.” Reagan chose guns. It turns out that when this country promotes guns, little money is available for working families. What has happened to the income of working families since Reagan? There has been a significant drop in the working-class standard of life and more inequality! More recently, a certain sector of the ruling class has decided that the higher level of inequality is an existential danger to the capitalist system itself. They are promoting a form of “inclusive capitalism” to avoid the pitchforks. “Inclusive capitalism” has no lasting substance, however, and cannot overcome the basic contradictions of capitalism. During the pandemic, it has been easier to make the case for a Keynesian economic intervention to alleviate the worst of the pandemic-aggravated economic crisis (on top of the already existing capitalist crisis). Underway are massive infusions of budgetary stimulus (fiscal stimulus) from the Federal spending budget plus a huge infusion from the Federal Reserve Bank (monetary stimulus). Combined between 2020 and 2021, they total about $6 trillion dollars. The bottom line, however, is that imperialism has never been good for the country nor good for the working class. It has been very good for the stock market! Biden’s interim national security strategic guidance, it turns out is a lot of smoke and mirrors! Confrontation over values?A populist leftist president in Latin America states that the main characteristic of conservatism (catchall phrase for capitalism and neoliberalist policy) is hypocrisy. By conservatism, he speaks of the ideology of resistance to change, of having to give up private unwarranted privileges and wealth. Most of this wealth is acquired through wage theft, corruption, tax avoidance, debt traps, and undemocratic practices. While the national security guidance talks about “democracy”, “ U.S. values” and “universal” values, what they are really talking about is making the U.S. finance capital more profitable around the world. The guidance document makes no mention of what happened during the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. No mention is made of passage of laws that essentially take away the right to vote in many states. No mention is made of the lies used to justify the war on and killing of the people of Iraq, the Afghan people, the Syrian people, the people of Yemen, Sudan, Somalia, and many more nations. No mention is made of the CIA rendition and torture programs around the world, including Guantanamo’s U.S. military base and Abu Ghraib in Iraq. No mention is made in the “national security” strategic guidance document about U.S. “undemocratic” support for the coup that overthrew the elected President of Bolivia, Evo Morales, efforts to overthrow the elected president of Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro, efforts to overthrow elected President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua or the U.S. supported coup that overthrew the elected presidents of Honduras, President Zelaya in 2009 (Biden was Vice- President then, nominated by Obama because of his foreign policy “expertise”). Obviously, no mention is made of institutionalized racism in this country and the consequent political instability. No mention is made of the consequences of savage capitalism (neoliberalism) introduced in the 1980s under Reagan in the U.S. and Thatcher in the UK. This economic policy has resulted in the loss of good-paying jobs and a lower standard of life for the working class, not only in this country but around the world. Confrontational meeting in AlaskaThe U.S. and China had a joint meeting (March 18-19, 2021) between the U.S. Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, U.S. National Security adviser, Jake Sullivan, Foreign Minister of China, Wang Yi, and chair of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission Office of the Chinese Communist Party, Yang Jiechi. The U.S. sanctioned 24 Chinese officials the day prior to the meeting. The U.S. State Department also came ready with preconditions to improved relations. The summit turned into a posturing and recrimination session on China and U.S. human rights. The facts point to this public confrontation as the real purpose of the U.S.- requested meeting. “China urges the U.S. side to fully abandon the hegemonic practice of willfully interfering in China’s internal affairs. This is a longstanding issue, and it should be changed.” Yang Jiechi urged “the abandonment of Cold War mentality and zero-sum game.” No communique was issued after this Biden Administration meeting with the Peoples Republic of China. Hopefully, this is not a lost opportunity to advance solution to common problems like the pandemic, climate change, nuclear proliferation, global economic recovery after the pandemic, and to engaging in cooperation to help solve issues affecting developing countries. Take the issue of vaccination against the pandemic. Ten developed capitalist countries are hoarding 80% of the vaccines. Mexico’s President Obrador, during an online meeting with Biden, asked the U.S. to share its vaccine. The reply by the White House press secretary was that “Joe Biden would not consider sharing its coronavirus vaccines.” U.S. vaccines were denied in spite of hypocritical talk about the enduring partnership between the U.S. and Mexico “based on mutual respect and the extraordinary bond of family and friendship.” Would you deny vaccines to your own “family”? Now, the U.S. plans to “lend” some of its oversupply of the AstraZeneca vaccines to both Canada and Mexico. This comes after some vaccinated Europeans experienced isolated blood-clot issues and many European countries temporarily suspended the use of that vaccine. Cyril Ramaphosa, President of South Africa and African Union chairman has criticized this vaccine nationalism. China, Russia, and other countries have sent their own vaccines to developing countries in Latin America, Africa, and other locations. Socialist Cuba has developed a new COVID-19 vaccine and, in contrast to developed capitalist countries, provided exemplary international health care solidarity. Mexico has received vaccines from Belgium, China, Russia, and India. Mexico also received the active ingredient for AstraZeneca from Argentina. Later, under international pressure and condemnation, the U.S. pledged $4 Billion to the World Health Organization’s COVAX program. If history is a possible indicator of future actions, the Biden administration intends to continue U.S. imperialist hegemony in a world that expects more multilateralism in foreign policy, respect for the national sovereignty of nations, and more international solidarity on common issues affecting the globe, such as pandemics, climate change, war prevention, labor migration, refugees, weapons control and global poverty alleviation. There have been some positive moves made by Biden including extension of the New Start Treaty with Russia and willingness to rejoin the Non-Proliferation Treaty with Iran. It didn’t help that Biden bombed alleged Iranian assets in Syria, however. There is an internal conflict between Biden’s foreign policy intentions and his domestic agenda. Biden plans to pursue infrastructure jobs, raising wages, student debt forgiveness, economic recovery, and other domestic issues. There is a growing domestic mass opposition and new coalitions created to oppose a confrontational foreign policy and a bloated military budget; its slogan is – Money for Jobs, Not for War! If you agree with this slogan, you are encouraged to join the coalition at moneyforhumanneeds.org. Biden says he wants to work with Mexico and Central American countries in a joint economic development program initiated by Mexico to alleviate the poverty and insecurity that is driving the labor migration from Central America and southern Mexico to the U.S. Nevertheless, Biden intends to keep Trump’s original 4,000 National Guard members on the southern border with Mexico, while continuing immigrant deportations and caging of 5,000 immigrant children. Biden only offers to help Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, all of which have right-wing governments allied with the United States. Countries left out include left-led Nicaragua plus Haiti. The main reason for the labor migration and refugee exodus is poverty, an effect of global imperialist policy. Other contributing factors include climate change, wars, and gang violence. Biden’s regional commanders (North America and Southern Command) also cautioned in a recent press conference about possible terrorists coming through the southern border. Sounds a lot like Trump’s racist and unfounded rhetoric! These outrageous remarks are an insult to Mexico. Martin Luther King warned, “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” The military budget in the U.S. takes about half the discretionary spending of the national budget, leaving little money to meet social needs. The U.S. spends (~$741 billion budgeted for 2021) more on the military budgets of the next 10 countries combined. AuthorAlvaro Rodriguez is a long-time labor and community activist. He writes from Texas. This article was first published at People's World

1 Comment

3/31/2021 Edna Griffin and The Fight to Integrate a Des Moines Drug Store. By: Travis SmithRead NowGriffin in her Women’s Army Corp uniform, photo courtesy of Fort Des Moines Museum and Education Center (source and owner of photo). Over 10 years before the civil rights sit-ins of the 1960s, like the one at the Woolworth’s in North Carolina, a coalition organized by a Communist Party member and others fought to desegregate a drug store in Des Moines, Iowa. In 1948 Iowa had a problem with racism. The state was north of the Mason-Dixon line, and many considered discrimination to be “not that much of a problem.” But a string of drug stores owned by the Katz family had been accused numerous times of violating civil rights laws; one letter to the NAACP described Katz’s treatment of Black people, saying, “Negro WACs and Nurses, even when wearing Uncle Sam’s uniforms, do not belong to the human race.” The NAACP tried and failed to prosecute Katz for the misconduct numerous times, each ending in acquittal or the accuser dropping out due to lack of witnesses. Enter Edna Griffin. On a hot day in July, Edna, John Bibbs, and Leonard Hudson entered Katz Drug Store in downtown Des Moines. Griffin and Bibbs took seats and ordered ice cream sundaes, but they were informed that the staff was not permitted to serve them because of their race. Eighteen months later, under the pressure of court losses and mass mobilizations and boycotts by a Black-white alliance against fascism organized by Edna Griffin, the Progressive Party, and the NAACP, Katz would agree to end all discriminatory practices. Edna Griffin moved to Iowa in 1947, with her husband Stanley. The pair had already been active in Nashville in fighting against fascism and for better wages for teachers, and they had joined the Communist Party. They were struck by the status quo of discrimination in Iowa. The vast majority of Iowans did not believe there was a problem. Indeed, while 83% of African American lawyers thought illegal discrimination was common, 87% of county attorneys thought it was not. Numerous court battles had already been fought and lost on account of “no witnesses.” In a state with a 99% white population, Black Iowans needed a way to convince white Iowans that discrimination existed, that it was a problem they should be concerned about, and that solving the problem depended on them. In consultation with the NAACP and members of the Progressive Party, Edna hatched a strategy to win in the courts and in the court of public opinion. The first step was to make Edna seem relatable to white Iowans. While the defense tried to paint her as a professional agitator who caused a disturbance, Edna’s legal team drove home the point that Edna was a respected, educated, middle-income young mother whose actions were perfectly reasonable for a hot day in June and that the central question of the case was whether the law had been broken. Of course, Edna was a tireless “agitator” whose Communist affiliation caught the attention of the FBI, but the perception that she could have been anybody was crucial to not only gaining sympathy with the all-white jury but also to addressing the thrust of the question in court: was this discrimination under the law, and did it live up to the democratic ideals Iowans held about their state? Griffin tied the battle against discrimination to the battle against fascism, an idea that held a bit of weight just a few years after World War II. At the trial Griffin stated, “I volunteered in the armed forces knowing full it was a jim crow army, to help establish the equal dignity and equal rights of my people.” Along with the battle in the courts, Griffin also fought in the street, organizing a series of protests, sit-ins, and boycotts designed to hurt Katz’s business. The two-prong strategy was necessary because, as Griffin put it, “Experience indicates that court action alone has not and cannot stop jim crow because the penalty exacted under the law is not sufficiently heavy.” As in the trials, the argument in the streets was made broadly as a fight against the forces of tyranny rather than as a narrow fight at one drug store. One brochure handed out during this time was titled, “Bill of Rights — Hitler Failed but Katz Is Trying” and read: A lawsuit is pending against Katz Drugstore but we want you to know why Jim Crow undermines the rights of every citizen, not just the victims. The “master race” idea poisons the mind with hate, distrust, and suspicion. This turns the minds of the people from high prices, low wages, and no housing to violence against one another. It happened in Germany, and it can happen here. Protest signs read, “The Bullets Weren’t for White’s Only. Don’t Buy at Katz” and “Counter Service for Whites Only. This is Hitler’s Old Baloney. Don’t Buy at Katz.” The two-prong strategy — which engaged the masses to demonstrate that everyone had an interest in ending the problem of racism — won the fight overall. Griffin won a criminal case against Katz in 1948, but the drugstore owners continued to bar African Americans until December 3, 1949, after more than a year of additional civil lawsuits and street protests. The success in either field of struggle depended on wins in both, and the appeal to white people’s broad collective interest rather than their individual self-interest was a winning strategy. The trials provided the context and legitimacy, and the work in the streets provided the economic and political force to make it happen. This strategy would prove itself time and again in the civil rights moments to follow throughout the 1950s and 1960s, perhaps most notably with figures like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. Edna Griffin would continue to play vital roles in progressive fights for decades after this moment, with the Black-white progressive coalition built during the drugstore struggle playing a key role in the Henry Wallace campaign, in desegregation fights nationally, against the atomic bomb, against the Korean War, for unionization, and in many other fights. Perhaps the most relevant endorsement comes from the FBI agent charged with tracking her: “She should not be underestimated as an individual. She is a very capable and intelligent person. She manages to get along with people and is always fighting for some noble cause.” Citations Noah Lawrence, “‘Since It Is My Right, I Would Like to Have It’: Edna Griffin and the Katz Drug Store Desegregation Movement.” Annals of Iowa 67, no. 4, pp. 298–330, 2008. AuthorTravis Smith is a pest control worker and father in Iowa who became an active member of the Communist Party in 2019 where he's been working to build the Edna Griffin Club, so named for a famous Iowan activist and Party member. His interests outside of politics include woodworking, sailing, and PC gaming. His son enjoys attending protests and fiddling with Daddy's boat This article was first published in Communist Party USA

On March 8, 2021, the Supreme Federal Tribunal (STF) - Brazil’s highest court - struck down all the criminal convictions against Brazil’s former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Monumental in its impact, this decision finally brought an end to a ruthless lawfare campaign against Lula. LawfareLula was imprisoned in April 2018 at the Federal Police headquarters in Curitiba as part of Operation Car Wash for alleged corruption. From the beginning, it was evident that Lula’s imprisonment was part of lawfare - the use of law for political motives. The Supreme Court ruled, on April 5, 2018 - after a threat from Brazilian Gen. Eduardo Villas Bôas - that defendants could be jailed even before their appeals had been exhausted. This regressive judgment allowed Judge Sérgio Moro to arrest Lula at a time when he was leading in all polls. In August 2018, the polls registered that 29% of the nation preferred Lula’s Worker’s Party (PT), while the political parties that were spearheading the anti-PT campaign were rapidly declining in terms of electoral strength. The presence of political bias in Lula’s imprisonment was confirmed when a range of materials and private conversations released by “The Intercept” proved that judge Moro discussed the case with the lead prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, to whom Moro gave advice about how to proceed with the case. Furthermore, the Car Wash prosecutors plotted to use the investigation to undermine the campaign of the PT in the 2018 election. In November 2018, Moro joined Jair Bolsonaro’s government as his Minister of Justice, thus leaving no doubts about the political nature of the judicial proceedings against Lula. Lula was released in November 2019 after serving 580 days, when the SFT agreed to examine his case on the basis of the judicial principle that no one can serve a sentence before it can be reviewed by the country’s highest court. Changing Political TidesIn a welcome move, the STF confirmed on March 23, 2021, the existence of misconduct by Moro in the cases involving Lula. According to Justice Carmen Lucia, the evidence that has emerged since 2018 “may indicate the infringement on the impartiality of the judge.” “What is being discussed here is something very basic: everyone has the right to a fair trial, that includes due process and also the impartiality of the judge…New information was presented to clarify doubts about evidence of the partiality of the judge overseeing the case.” The legal affirmation of the biased nature of Operation Car Wash is reflective of Brazil’s changing political tides. Opinion polls suggest that Lula is the best-placed politician to challenge neo-fascist Bolsonaro in 2022 elections. This was expected. The Bolsonaro administration’s toxic mix of pandemic mismanagement and savage neoliberalism stands in sharp contrast to Lula’s social sensitivity. At a press conference held at the headquarters of the ABC Metalworkers’ Union in São Bernardo do Campo in the metropolitan region of São Paulo after the annulment of convictions, Lula heavily criticized the Bolsonaro government: “I need to speak with you about the situation in this country. It would be an error on my part to not mention that Brazil did not have to go through this.” “Many people are suffering. This is why I want to express my solidarity with the victims of coronavirus and the healthcare workers. And above all, the heroes of the SUS [Unified Health System], that were even politically discredited. If it wasn’t for the SUS, we would have lost many more people to coronavirus.” Lula’s remarkable ability to connect with the poor masses is a direct result of his sustained involvement in grassroots politics. Born in poverty in 1945 in the northeastern state of Pernambuco, Lula emerged on the national scene from the late 1970s as a confrontational union leader. On winning presidency in October 2002 after three failed attempts, he toured the country extensively, talking to the oppressed members of the society about his own life and the larger struggle for equality and justice. Today, it is highly likely that Lula - whether he runs for presidency or not - will help the Left to regain power in Brazil. AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. 3/30/2021 Germany’s Linke (the Left Party) Comes Out of its Convention United - by Victor GrossmanRead NowJanine Wissler and Susanne Hennig-Wellsow were elected as new party leaders. LINKE Things worked out quite differently than many in the Berlin media said they would at the congress of the LINKE, the country’s left-wing party. The pandemic had forced postponements from June 2020 to October 2020 and from last October to March 2021, with most of the 580 delegates at home in front of a screen, microphone, and camera. Only the socially-distanced, masked leaders sat in a sparsely occupied hall in Berlin. Other political parties are meeting that way too. The bitter, possibly fatal inner conflicts, greatly feared by some, greatly desired by others, simply did not happen. Unlike the angry quarrels, hostility, and near split-ups which troubled some earlier congresses, this time there was an amiable, friendly atmosphere throughout. No surprise, at least for most members, was the choice of new party leaders. Their predecessors stepped down as required after two four-year terms (plus extra months due to the postponements). Only outsiders may have been surprised that both new co-chairs were women, Janine Wissler and Susanne Hennig-Wellsow, which was new. But many were indeed moved to see the two so supportive of one another, each congratulating the other on her (separate) election and both assuring party members that they would get along very well while diving into the tough tasks ahead; a year full of elections in six states and, on September 26, in all Germany, and with the LINKE now polling at a worrisome 7 or 8 percent, too close to the 5 percent cut-off point below which a party is not entitled to seats in the country’s parliament. Who are the two new leaders, no longer a male-female team but still the customary East-West duo? Janine Wissler, 39, has led the LINKE opposition caucus in the legislature of the West German state of Hesse since 2014. She is known as a fighter. In the last election campaign, she covered her whole state by bicycle, speechmaking all along the route, and winning more LINKE votes than the party won in most of West Germany. More recently, joining the protest against chopping down part of an ancient forest to build another highway, she stayed a while in one of the high tree huts aimed at holding off loggers and the police. Susanne Hennig-Wellsow, 42, her co-chair, is also known to be plucky. Originally a speed skater, a very good one, she switched to educational issues in her East German home-town of Erfurt in Thuringia, and quickly climbed to a position equivalent to that of Janine Wissler’s just across the former East-West border, becoming chair of both the state party and its caucus in the legislature. But unlike Wissler, she was not in opposition. Thuringia is the first and only German state with a LINKE leader, Bodo Ramelow, as minister-president (like a governor), because his party won the most seats. Since 2014 he has headed a shaky coalition with a small Social Democratic and even smaller Green caucus. Hennig-Wellsow gained unusual fame last year after a conservative politician pushed Ramelow out as head of state, but only by accepting the votes of the neo-Nazi Alternative for Germany party (AfD), which, despite the leading role of the state’s Red, Red, Green coalition, is stronger and more rabid in Thuringia than anywhere else. Tradition demanded that party-leader Hennig-Wellsow present the winner, any winner, with congratulatory flowers. She approached him, then suddenly let the bouquet fall to the floor. Impolite, but most anti-fascists rejoiced at what became a top YouTube hit. After a huge public outcry, the man had to step down three days later and Ramelow came back — with Hennig-Wellsow. Now, these two state leaders head the national party, and though they disagree sharply on some issues, they are in agreement on a host of others. A striking feature of the LINKE congress that just ended was the age of the delegates. Among the delegates who spoke up electronically, with contributions strictly limited in time because so many wanted to speak, the number of young people and women was greater than ever before. This marked a change from the past when so many were aging, often male, and frequently former members of the old Socialist Unity Party, the ruling party in the GDR. That generation is dying out. Ten years ago over 50% of Die Linke’s membership lived in the five smaller states of East Germany. Now they make up 38 percent of a total of 60,000. With all due respect to these truly “Old Faithful,” the trend toward a new, younger generation is a greatly-needed cause for hope. And so is their militancy — which was reflected in the words and the spirit of Wissler and Hennig-Wellsow. Most of these young members called energetically for more visible and militant action in all causes for which the party stands. A key theme was helping people recover from the pandemic, which is causing heavy debts, hardships, job losses, and bankruptcy for tens of thousands of small firms, retail shops, restaurants, and cultural workers while the biggies, from Amazon to Aldi, from Daimler-Benz to BMW rake in mountains of euros for their owners and stockholders. The LINKE demands genuine taxes on the wealthy, higher wages for the workers —a 15-euro minimum wage — and more for children and pensioners. It means much closer ties with the unions and their struggles. Some of the unions sent greetings to the congress, which still required a bit of courage. Many stressed the related fight for the environment, too often neglected and left to the Greens. But the Greens, till now in second place in the polls ahead of the Social Democrats (SPD) but well behind the twin “Christian Union” parties, have moved ever closer to arrangements with big business, downplaying the needs of working-class people and even abandoning major principles in order to gain or keep cabinet positions, as in Hesse, where their coalition ministers concurred in sacrificing forest sectors to an unnecessary highway extension (where Wissler did some needed “tree-hugging.”) Many delegates warned of further hospital privatization and supported the fight for affordable, publicly-owned housing to outpace the profit-based gentrification expanding through most cities. There was praise for the LINKE in Berlin; it led local coalition partners SPD and Greens in pushing through a rent control law reversing the worst over-pricing and forbidding most increases. It also defied Green foot-dragging and SPD opposition to a referendum to buy out (or “confiscate”) Berlin’s biggest real estate giants. Both of the two new party leaders and many delegates called for a constant, vigilant resistance to the growing menace of the fascists, some loosely bound up in local thug gangs and underground killer units, others organized on a party basis or embedded in the police, the armed services or as suspicious secret agents of the FBI-type Constitutional Defense Bureau. There was also general agreement on re-directing billions spent on armament purchases and production toward the repair of decrepit schools, rutty roads, unsafe bridges, and all public facilities. But general agreement on this edged onto questions dividing the party for years. Some members — and many in leadership — hope keenly that the LINKE can join with the Social Democrats and Greens in a national, governing “left-of-center coalition,” as in current state governments in Thuringia and Berlin. Former harsh rejection by the other two of any connection with the “former rulers of the GDR dictatorship” has now weakened, especially if the votes of LINKE deputies can help them over the 50% margin to victory. Since both the SPD and the LINKE adopted the color red as their symbol, this would be a Green-Red-Red coalition, or G2R, or RGR, depending on who would be top dog. Such an alliance, say its advocates, would be a bar against the right, meaning the Christian sister parties, the conservative Free Democrats, and the fascistic AfD. The state and the national levels differ in many ways. Most important, only the latter deals with foreign and military policy, which erects big, important hurdles. Both SPD and the Greens insist on two conditions for an alliance: the LINKE must abandon its opposition to NATO and to sending Bundeswehr troops outside German borders, even on UN missions. That is their red line; No-NATO means No-go! And well-armed German troops must be able to flutter black-red-golden flags from Kabul to Bamako, from masts in the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, or any sea or coast where it serves German purposes. Roll up the tanks, drones, fighters, and armed frigates! Some LINKE leaders call for compromises. A humanitarian mission for the UN now and then should not be a major hurdle, while replacing NATO with a Europe-wide security agreement, including Russia instead of threatening it, is currently pure fantasy, they say. In a highly controversial open letter, Matthias Höhn, a leading LINKE member, said that such matters can be agreed upon, Germany need not totally reject U.S. demands for 2% of its budget for military build-up but might cut it to 1%, with the other 1% diverted to development aid for countries of the south. His opponents were quick to reply; they insisted that Germany was threatened by no one; the Bundeswehr was in essence an instrument of the same expansive powers which have determined bloody German policy for over a century. Bombing Belgrade and Afghanistan was also called “humanitarian,” they note, and any backsliding in these matters was really a foot in the door, a dangerous foot, and would cancel the basic claim by the LINKE to be the one and only party of peace in the Bundestag. This question has implications for even more basic questions. Does the LINKE support or oppose Germany’s present capitalist social system? Many leaders in the East, often having experienced advantages attached to cabinet seats on a state level, insist that the LINKE can only exert political effect to improve life if it takes part on a governmental level. The other side claims that the LINKE, as a tolerated little brother in such a coalition, would be granted a few lesser cabinet ministries but be easily outvoted on important policy questions, foreign or domestic, with only two options — bow down or quit. “No,” they say, the party wants improvements but sees the need for a full social switch. That means active opposition and not becoming part of “the Establishment,” a role which has cost it dearly in eastern Germany in poll results, elections, and reputation. Essentially, some say that support for socialism and being part of the so-called establishment contradict one another. The dividing line also affected the two new leaders. Hennig-Wellsow from Thuringia is ready to consider a GRR coalition, even with a compromise or two. Isn’t that what realistic politics sometimes requires? Wissler from Hesse says No; she wants no cozy, weak-kneed cabinet seat for LINKE. Let the SPD and Greens change their position, she says, and adopt a genuine peace policy that abandons dangerous “east-west” confrontation. The differing viewpoints were put to a test during the vote for six deputy chairpersons. Matthias Höhn, who sent that letter proposing a retreat on armaments and deployment, received 224 voters. Tobias Pflüger, a disarmament expert opposed to any dilution of peace positions, beat him out with 294 votes. And it was Pflüger’s views which were more frequently reflected by the overwhelmingly young speakers’ list. Many note that the coalition question is purely hypothetical anyway. With Greens and SPD now polling at 17 percent each and the LINKE at 8 percent (but hoping to get back to double digits), reaching 50 percent is still a dream. That explains why so many stressed instead the need to fight far less in parliaments or party meetings but far more in the streets, factories, and colleges, among machinists, teachers, medical personnel, supermarket employees, truck drivers, and all the places where those who do the country’s work must move in defense against current attacks on living standards and values. This must reach at least as many women as men, both young and old, all sexual orientations, and definitely, those hit hardest, the millions with immigrant backgrounds. Hopeful symbols were the hearty greetings from the Alevite Turkish community, from several major unions, and young activists in Fridays for Future. Disagreement on key issues could not and will not be ignored. But the happy surprise was that this did not lead to a split, which would have meant LINKE if not general left-wing political demise! The sides agreed to disagree and now work together to win supporters — and votes — in the six state elections and the national election soon challenging the party. There was one other aspect which surprised many and deserves attention: how many participants, especially the younger ones, dropped past shyness and stated that the current social system, now proving its decay and inhumanity more clearly than ever, must be replaced. The goal was also named, without many former taboos; a socialist economy, no longer determined by a tiny cabal whose lust for unearned profit caused a huge, growing gap between billionaire luxury and billions facing deprivation and despair. If this new fighting spirit and renewed orientation can be maintained, the LINKE party could play a far more potent role in strengthening opposition within Germany. And after the vicious defeat of Jeremy Corbyn’s fight in Britain and with the weakness of leftist parties in France, Italy, and elsewhere in Europe, a militant Left in central, powerful Germany could regain the importance it once possessed in the heyday of people like Rosa Luxemburg — who was born 150 years ago, on March 5, 1871! AuthorVictor Grossman is a journalist from the U.S. now living in Berlin. He fled in the 1950s in danger of reprisals for his left-wing activities at Harvard and in Buffalo, New York. He landed in the former German Democratic Republic (Socialist East Germany), studied journalism, founded a Paul Robeson Archive and became a freelance journalist and author. His books available in English: Crossing the River. A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany. His latest book, A Socialist Defector: From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee, is about his life in the German Democratic Republic from 1949 – 1990, tremendous improvements for the people under socialism, reasons for the fall of socialism, and importance of today's struggles. This article was first published in People’s World March 4, 2021.

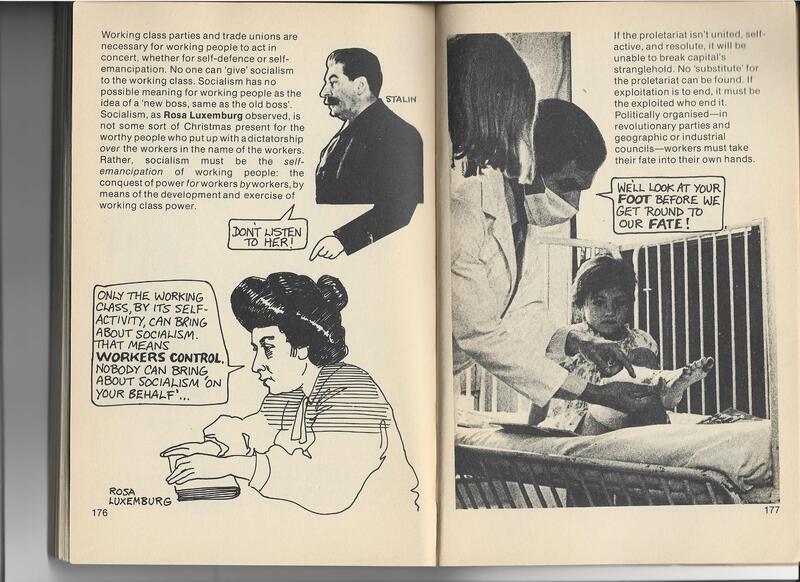

Two books by Slavoj Zizik (“Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism”, 1038 pp., and “Living in the End Times”, 504 pp.) were reviewed by John Gray ("The Violent Visions of Slavoj Zizek") in the July 12, 2012 issue of The New York Review of Books. Professor Gray is to be commended for wading through 1500 pages of undiluted Zizek (and perhaps saving some of us from having to do so). I propose to review Gray's article and thus give a meta-critique, as it were, of some of Zizek's views as presented by Gray. If anyone is stimulated to go on to read Zizek so much the better, or worse as the case may be. You can find Gray's original article here:The Violent Visions of Slavoj Žižek by John Gray | The New York ...…. My reflections are divided into five parts. 1.) Zizek has produced over 60 books in the last two decades or so and has become one of the most famous public intellectuals in the West; propounding a sort of non-Marxist Marxism. The NY Review article has a picture of the philosopher sitting up in his bed in Ljubljana, Slovenia with a framed picture of Stalin on the wall behind him. New Yorkers may remember that he addressed the OWS movement in Zuccotti Park. So what is Zizek's message? At one time he was a member of the Communist Party of Slovenia but he quit in 1988 and has since articulated a critique of capitalist society more influenced by a strange version of Hegel than by Marx. Gray says a CENTRAL THEME of ZZ's work "is the need to shed the commitment to intellectual objectivity that guided radical thinkers in the past." Intellectual objectivity is a BOURGEOIS ILLUSION and most radicals, at least most Marxists, have always been partisans for the working class. Gray should be clearer about what ZZ is trying to express with this criticism. ZZ wants to, in his own words, "repeat the Marxist 'critique of political economy', without the utopian-ideological notion of communism as its inherent standard." We had better be pretty familiar with, at least, the three big volumes of Das Kapital before we decide on accepting ZZ's "repeat" of Marx's project! ZZ doesn't think the world communist movement was radical enough. He writes, "the twentieth-century communist project was utopian precisely insofar as it was not radical enough." What does this mean? "Marx's notion of the communist society," ZZ writes, "is itself the inherent capitalist fantasy; that is, a fantasmatic scenario for resolving the capitalist antagonisms he so aptly described." 2.) It is all very well for ZZ to put down what he thinks is Marx's notion of communist society, but as a matter of fact neither Marx nor Engels spent much time speculating about a future communist society precisely because they thought such idle speculation unwarranted; they were more interested in dissecting the nature of capitalism and the methods needed to overthrow it. ZZ at least follows their example as Gray points out that nowhere in the 1000+ pages of “Less Than Nothing” does ZZ discuss what he thinks a future communist society would/should be like. What he does discuss says Gray (who calls the book a "compendium" of all ZZ's past work) is his new and unique interpretation of Hegel (by way of Jacques Lacan's unscientific reinterpretation of Freud) and its application to a new reading of Marx. In other words, the arch-rationalist Hegel is viewed from the point of view of the irrationalist Lacan and this mishmash of misinterpretation is used to explain Marx to us. One of Lacan's teachings is that REALITY cannot be properly understood by LANGUAGE. Which, if true, would make science impossible and bar us from ever understanding the nature of the world we live in. But it is language that Lacan uses to tell us something about the nature of reality, i.e., that language can't do that! Lacan also rejected Hegel's view that Reason is imminent in history. Big deal-- Marx and the entire history of post-Hegelian materialism has rejected this notion of Absolute Idealism for the last 150 years or more and no one needed Lacan to tell us about the outmodedness of this Hegelian notion. But ZZ thinks that Lacan has shown more than just that Hegel was wrong to think that Reason Rules the World. ZZ, says Gray, thinks that Lacan has shown "the impotence of reason." This is a fundamental attack on the legacy of the Enlightenment upon which all attempts to understand the world scientifically and rationally are based; it is ultimately a fascist outlook. ZZ has also been influenced by the contemporary French philosopher Alain Badiou (who has been himself influenced by Lacan and, shudder, Heidegger and has developed a form of Platonic Marxism). Using some of Badiou's ideas ZZ constructs his own view of "dialectics" as being based, Gray says, on "the rejection of the logical principle of noncontradiction." ZZ imputes this view to Hegel and thus claims Hegel rejected reason. ZZ writes that for Hegel a (logical) proposition "is not really suppressed by its negation." ZZ credits Hegel with the invention of a new type of logic: "paraconsistent logic." This is really confused. We have to distinguish between FORMAL LOGIC where the law of non-contradiction reigns, and Hegel's metaphysics or ontology of Being where there are different sorts of logic at work-- subjective logic (thoughts) and objective logic (the external world). But even here it is not a question of a "proposition" being suppressed. Hegel says neither things nor thoughts care for contradictions and when contradictions appear there is a movement to overcome and resolve them on higher levels of understanding and reason-- this is the inherent motion driving the "dialectic" a motion to overcome and eliminate contradictions. Despite these considerations, ZZ forges ahead with his ill conceived "paraconsistant logic." "Is not," he writes, "'postmodern' capitalism an increasingly paraconsistant system in which, in a variety of modes, P is non-P: the order is its own transgression, capitalism can thrive under communist rule, and so on?" At this point Gray quotes a long passage from “Less Than Nothing” in which ZZ lays out the main theme of his book dealing with the response needed to "postmodern" capitalism: "The underlying premise of the present book is a simple one: the global capitalist system is approaching an apocalyptic zero-point. Its 'four riders of the apocalypse' are comprized by the ecological crisis, the consequences of the biogenetic revolution, imbalances within the system itself (problems with intellectual property; forthcoming struggles over raw materials, food and water), and the explosive growth of social divisions and exclusions." ZZ misses here the fact that the four horsemen of the capitalist apocalypse are simply four manifestations of the same fundamental contradiction underpinning the entire capitalist system, namely, the private appropriation of socially created wealth. At this point Gray launches an unjustified attack on ZZ, accusing him of ignoring "historical facts" such as the environmental damage done by the Soviet Union and to the countryside by Mao's "cultural revolution." You can't just blame capitalism since both the SU and China had centrally planned economies. History, Gray says, does not provide any evidence that replacing capitalism by socialism will better protect the environment. What does "history" really show? Just take the case of the Soviet Union. The soviets tried to build socialism but were attacked by the western capitalist powers from day one. They had to take short cuts to industrialize and fend off the Nazi attack, and then the Nazi successor state as US imperialism took up the anti-communist crusade. China has a similar history. All parties in this conflict were societies still under the rule of the law of value, the reigning economic force in commodity producing economies. Socialism did not thrive (nor could it have thrived) in the primitive backward conditions it developed under in the 20th century. If socialist central planning were to replace the social anarchy of capitalism in the advanced capitalist states of the west (including Japan) where production could be based on need not profit (thus overcoming the law of value) we would be able to reign in our four apocalyptic horsemen and literally save the planet. This is what "history" really suggests and Gray's attack on ZZ on this issue is unjustified. However, his next attack on ZZ has merit. ZZ's "Marxism" lacks any relation to the actual class struggle and does not reflect Marx's commitment to a materialist dialectic grounded in the empirical reality of day to day economic struggle. Here is what ZZ says: "Today's historical juncture does not compel us to drop the notion of the proletariat, or of the proletarian position--- on the contrary, it compels us to radicalize it to an existential level beyond even Marx's imagination. We need a more radical notion of the proletarian subject [i.e., the thinking and acting human being], a subject reduced to the evanescent point of the Cartesian cogito, deprived of its substantial content." This is just ridiculous. The worker treated in complete isolation from his/her class and relation to the means of production, treated as an isolated human being, is simply retrograde bourgeois idealism and in no way a more radical conception than that of Marx. It is an abandonment of the concept of the proletariat, or working class, as understood by Marxists. 3.) ZZ in fact abandons objectivity for a completely subjective position. "The truth we are dealing with here," he writes, "is not 'objective truth' but the self-relating truth about one's own subjective position; as such it is an engaged truth, measured not by its factual accuracy but by the way it affects the subjective position of enunciation." In other words, "truth" is what inspires me to feel good about my chosen path-- my "project" and reinforces me in my actions to attain the fulfillment of my "project." ZZ thinks a communist society would be nice but doesn't think it's really possible to attain but that doesn't mean we should not act up and agitate against the status quo. ZZ also thinks it’s ok to engage in terror if it helps my subjective enunciation. He supports Badiou's position in favor of "emancipatory terror" and lauds Mao's Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. To top off this witch's brew of petty bourgeois pseudo-revolutionary clap-trap, ZZ, Gray points out, "praises the Khmer Rouge." For all the meaningless killings Pol Pot and his gang indulged in ZZ does not blame their fall from grace as related to their barbarity. "The Khmer Rouge, were," he says, "in a way, not radical enough: while they took the abstract negation of the past to the limit [this is how a "Hegelian" refers to the killing fields!-tr] they did not invent any new form of collectivity." Would a new form of collectivity have justified their actions? [As we shall see ZZ rejects these criticisms by Gray on the grounds that his theory of violence has been misunderstood]. ZZ even goes so far as to call himself a Leninist. Gray gives a quote from a 2009 interview where ZZ remarks that: "I am a Leninist. Lenin wasn't afraid to dirty his hands. If you can get power, grab it." Gray is right to think that Lenin (as well as Marx) would hold ZZ's views in contempt. Lenin recognized the need for violence, it would be forced upon the workers by the ruling class, but he never celebrated it in the manner of ZZ who thinks it should be applied in a terrorist manner as a morale booster for the radical movement even though a successful revolution to get rid of capitalism is impossible. Gray gives another gem from ZZ on this topic: "Francis Fukuyama was right: global capitalism is 'the end of history.'" Very few, if any, people claiming to be Leninists believe that Fukuyama was right; I don't think, based on some of his current writings, that even Fukuyama thinks he was right. 4.) In this section I will deal with some valid points Gray makes against ZZ's fascination with the cult of violence, but points that are tarnished by Gray's own hyper cold war anti-communism and distortion of facts. ZZ does not think class conflict has an objective basis, according to Gray, who produces this quote from ZZ maintaining that class war is not "a conflict between particular agents within social reality: it is not a difference between agents (which can be described by means of a detailed social analysis), but an antagonism ('struggle') which constitutes these agents." It is therefore ultimately subjective-- just the opposite of what Marx and Lenin held. To illustrate his position ZZ discusses the collectivization of agriculture and the struggle against the kulaks in the USSR in the 1920s and 30s. ZZ makes a valid observation that often non-Kulak poorer peasants joined with the kulaks in opposing collectivization. This was a case of false consciousness. Americans are familiar with this phenomenon when they observe working people and minorities voting for the Republican Party and conservative candidates. ZZ says the Kulak non-Kulak boundary was often "blurred and unworkable: in a situation of generalized poverty, clear criteria no longer applied and the other two classes of peasants (poor and middle peasants -tr) often joined the kulaks (rich peasants- tr) in their resistance to forced collectivization." ZZ goes on to say, " The art of identifying a kulak was thus no longer a matter of objective social analysis; it became a kind of complex 'hermeneutics of suspicion," of identifying and individual's 'true political attitudes" hidden beneath his or her deceptive public proclamations." This is, by the way, the same "hermeneutics" Americans have to use, following the maxim that "all politicians are liars and say one thing but do another," when they try to figure out what candidates are saying and how they will actually behave once in office. ZZ is wrong to think of this as a subjective process of self identification. Cases of false consciousness have objective social conditions (miseducation, prejudicial propaganda, poverty, illiteracy) as their causes. Gray is wrong, I think, to call ZZ's view "repugnant and grotesque" because he appeals to hermeneutics and doesn't criticize Stalin for killing millions of people but for using Marxist theory to try and explain what the actions of the USSR were with respect to collectivization. The idea that Soviet policy was to bring about forced collectivization by killing millions of people is a relic of cold war bunko. I recommend Michael Parenti's “Blackshirts & Reds: Rational Fascism & the Overthrow of Communism” for a balanced discussion of the role of violence in Soviet history. However, ZZ is to be faulted for rejecting using Marxist theory to understand and explain political actions. He says that a time comes to junk theory because "at some point the process has to be cut short with a massive and brutal intervention of subjectivity: class belonging is never a purely objective social fact, but is always also the result of struggle and social engagement." But you cannot have a successful people's movement (struggle and engagement) without a correct analysis of the purely objective social facts-- otherwise the movement has to rely on spontaneity and no movement has grown and prospered that based itself on spontaneity. An idea of how far down the wrong road a social theorist calling him/herself a "Leninist" can wander is revealed by ZZ's attitudes towards Hitler and the Nazi apologist Martin Heidegger. Concerning Heidegger, ZZ writes, "His involvement with the Nazi's was not a simple mistake [of course not-- it was the essence of his world view-- tr] , but rather a 'right step in the wrong direction.'" How does ZZ arrive at this? He has a new reading of Heidegger to propose. He says, "Reading Heidegger against the grain, one discovers a thinker who was, at some points strangely close to communism…." Gray points out that ZZ claims that the radically pro-Hitler Heidegger of the mid 1930s could even be classified as "a future communist." Indeed. What future does ZZ have in mind? Heidegger died in 1976 without ever, to my knowledge, having become any kind of communist. ZZ thinks Heidegger was wrong, but also kind of right, in being a follower of Hitler, because there was a big problem with Hitler. Here is what it was, according to ZZ's own words quoted by Gray: "The problem with Hitler was that 'he was not violent enough,' his violence was not "essential" enough. Hitler did not really act, all his actions were fundamentally reactions, for he acted so that nothing would really change, staging a gigantic spectacle of pseudo-Revolution so that the capitalist order would survive…. The true problem of Nazism is not that it 'went too far' in its subjectivist-nihilist hubris [ I am tempted to say it takes one to know one- tr] of exercising total power, but that it did not go far enough, that its violence was an impotent acting-out which, ultimately, remained in the service of the very order it despised." There is so much wrong with this that I hardly know where to begin. In the first place there was only one socio-economic order at any rate that Hitler "despised" and wanted to destroy-- that was the order represented by the Soviet Union (he also despised and wanted to destroy the Jews.) Hitler used all the power at his disposal to accomplish his aims. It is impossible to conceive of what destruction Hitler could have wrought if had used (and had) the means to wreak even more violence on the world that he in fact did. He would not have destroyed capitalism as that was the economic order he furthered in Germany-- it was socialism, Marxism that he wanted to destroy. The Nazi's also rejected bourgeois democracy-- but because it was too weak to save the West from the hoards of semi-barbaric Bolshevik Untermenshen waiting to burst out of the Soviet Union and inundate Aryan Europe. If World War II was an impotent acting-out, I shudder to think what Hitler could have achieved if he was on ZZ's political viagra. But what about the Jews? What about anti-Semitism? Gray suggests that ZZ's attitude towards eliminating anti-Semitism from the world would also involve eliminating the Jews. This may or may not be so but it does not make ZZ an anti-Semite; it only shows, if that is what he means, that he accepts the ultra-right Zionist view that non Jews will always be against Jews and the only solution is an exclusively Jewish state. Well, what does ZZ say about all this? He states that "The fantasmatic [ZZ's own word for "fantastic"- tr] status of anti-Semitism is clearly revealed by a statement attributed to Hitler: 'We have to kill the Jew within us.'" He continues: "Hitler's statement says more than it wants to say: against his intentions, it confirms that the Gentiles need the anti-Semitic figure of the "Jew" in order to maintain their identity. [Oh my! I hope Herr Hitler is not the representative spokesperson for the "Gentiles." Hitler's statement doesn't confirm anything other than his own personal anti-Semitism-tr] It is thus not only that 'the Jew is within us'-- what Hitler fatefully forgot to add is that he, the anti-Semite, is also in the Jew. What does this paradoxical entwinement mean for the destiny of anti-Semitism?" Gray admits to having problems trying to figure just what ZZ means (he is too prolix and uses terms out of context from different philosophies to describe his own quite different views) but it seems quite a stretch to suggest that ZZ may be soft on anti-Semitism. ZZ himself has taken great umbrage at Gray's comments in this review and has penned a response that it is well worth reading and claims to set the record straight on this issue. [“Slavoj Zizek Responds to His Critics”] 5.) An example Gray gives of using terms out of context is ZZ's assertion that one may say that Gandhi was more violent than Hitler. Why would anyone want to say that except for "shock value?" ZZ says, in his reply to Gray, that Gray has misinterpreted him. ZZ believes in a type of violence in which "no blood is shed" and then refers to Gandi's struggles against the British in India-- usually referred to as based on "nonviolence." Since "nonviolence" is a special sort of "violence" it appears that since Ghandi was more nonviolent than Hitler he was more violent than Hitler. This is the "Hegelian" dialectic run amuck. Here is another example of ZZ, saying nothing according to Gray, engaging in meaningless wordplay. "The … virtualization of capitalism is ultimately the same as that of the electron in particle physics. The mass of each elementary particle is composed of its mass at rest plus the surplus provided by the acceleration of its movement; however, an electron's mass at rest is zero [sic], its mass consists only of the surplus generated by the acceleration, as if we are dealing with a nothing which acquires some deceptive substance only by magically spinning itself into an excess of itself." I'm not sure what ZZ is trying to say here about electrons, let alone capitalism (is surplus value "magical") but I don't think the rest mass of an electron is zero in the first place. For what it is worth Wikipedia says "The electron rest mass (symbol: me) is the mass of a stationary electron. It is one of the fundamental constants of physics…. It has a value of about 9.11×10−31 kilograms or about 5.486×10−4 atomic mass units, equivalent to an energy of about 8.19×10−14 joules or about 0.511 megaelectronvolts." Granted it is a very small mass, an electron is, after all, a very small particle-- but it is not zero. ZZ expects us to read 1038 pages of this stuff! It might be a good reference book to ZZ ideas-- which don't seem to be very Leninist-- the index has 10 references to Lenin while Lacan has over 2 columns devoted to his views! Gray is a hostile reviewer, but he is also hostile to Marxism, nevertheless, his review calls into question ZZ's basic methods of thinking and expressing himself (Gray says he represents "formless radicalism"). To get some idea of where Gray is coming from (I don't think it's a very nice place since it's anti-Enlightenment) check out the following: John N. Gray - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Modified and republished from Political Affairs.

3/28/2021 Biden's 'Killer' Comment About Putin Reflects Obsolete Foreign Policy. By: John WojcikRead NowBiden, at the time vice president, right, speaks to Putin, then the Russian Prime Minister, second left, during a meeting in Moscow, March 10, 2011. The two are now face each other as presidents of their respective countries. | Alexander Zemlianichenko / AP I want to start this critique of Biden’s developing foreign policy by stating clearly and unequivocally that his $1.9 trillion rescue plan deserves total support from everyone in our country. It is nothing less than a dramatic disavowal of the right-wing era launched by Ronald Reagan some 40 years ago. Although Biden deserves praise for his domestic policy so far, his characterization on national television of Russian President Vladimir Putin as a “killer” was just another indication of what is, unfortunately, turning out to be a dangerous trend in the foreign policy he is pursuing. While his domestic policy radically departs from what we have seen in the U.S. over the last 40 years his, foreign policy—executed by stalwart representatives of the old establishment—is failed business as usual. And the unfortunate reality is that a continuation of the policy of military domination of the entire world will sooner or later require turning away from progressive domestic priorities. As Biden begins his presidency, we are in a different and new world, one that did not exist in the Reagan-Bush-Clinton days of neoliberalism. The planet is in a very real climate emergency and is reeling under a global pandemic. Super recessions and depressions are crippling many countries economically. The wealth gap is growing day by day, and corruption in government, which has always been a problem, is even worse now, with scandals happening in almost every country in the world. Also worse than ever are the attacks on democracy happening in nations that have previously prided themselves as beacons of freedom. Solutions for these unprecedented problems will require unprecedented international cooperation. This is not the time then for the president of the United States to be calling the president of Russia, the second-largest nuclear power on earth, a “killer.” There are indeed plenty of killers running plenty of countries these days, as there have been in the past, including in our own. But the crises of today require cooperation between the two largest nuclear powers. Calling Putin a “killer,” however, reflects some real and far more dangerous trends in U.S. foreign policy. It reflects the control still being exercised by the old foreign policy establishment that played such a big role in bringing us the world-wide mess we have today. The U.S., thanks to the old foreign policy establishment, has almost 800 military facilities around the world. The new domestic and worldwide realities of today require dismantling of that network of bases. That will require changing the thinking about what constitutes national security. That shift will have to be as big if not bigger than the change we have seen from the Biden administration when it comes to domestic policy. For starters, the U.S. will have to stop military adventures around the globe, including the confrontational ones on Russia’s borders. Calling Russia’s leader a “killer” while the U.S. threatens that country with our troops along its frontiers is hardly helpful to the cause of re-ordering our priorities. Likewise, U.S. military confrontation with China in the South China Sea will not be at all conducive to the necessary reordering of priorities. There is no real indication yet that Biden is moving in the direction of ending confrontation with either Russia or China. In Afghanistan, the United States has been at war for more than 20 years. Trillions of dollars have been spent on that war. Many have died. Biden is now signaling U.S. troops will stay there beyond the date which Trump had claimed American forces would pull out. What amounts to institutionalized warfare, it seems, is something Biden is willing to continue. There is no hope of getting back what has been lost in Afghanistan. The only prudent course is to get U.S. troops out of there. Biden, during his campaign for the White House, promised to revive the Iran nuclear deal he helped negotiate when he was vice president. He promised to also bring back the constitutional role of Congress in declaring war. But he instead ordered the bombing—over the objection of Democratic senators who called it a violation of the War Powers Act—of what he said was an Iranian-backed outpost in Syria. In addition, he has delayed removal of 900 U.S. troops who are uninvited occupiers in Syria. He is maintaining troops in a sovereign country against its will and has ordered a bombing in that same country’s territory. Biden said he is reviewing our drone policies, but so far, that review has resulted in more focused targeting and no indication that use of killer drones will be ended. He is continuing U.S. support for regime change by continuing inhumane sanctions against Venezuela—sanctions clearly intended to overthrow its government. To no avail, the UN has called on the U.S. to end its cruel blockade tactics that deny medicine and food to the Venezuelan people. And back to Russia, Biden is ratcheting up dangerous confrontation with that country. In the next few weeks, Biden said, in answer to a question on national television, that “we will see” how he retaliates for last year’s SolarWinds hack of U.S. cyberinfrastructure—for which Russia was allegedly responsible. Knowledgeable sources say the administration will approve still more sanctions on Russia and clandestine cyber actions against Russian state institutions. Such an escalation is likely to trigger more and worse cyberattacks by both sides. Is that what we really want right now? In the long term, that will do no good at all for either the American or the Russian people. On China, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken has called relations with China “the biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century,” with the administration making a show of not just confronting China economically but also militarily in the South China Sea. U.S. naval maneuvers there continue. As the administration does this, the Republicans put forward continued accusations in public congressional hearings that the “Chinese Communist Party” is responsible for both the pandemic and for economic problems in the U.S. resulting from the pandemic. Such anti-China rhetoric inflames the international situation while also fueling domestic anti-Asian hate crimes and attacks. The United States cannot focus on and help solve the climate crisis, the pandemic, and worldwide economic disasters, including inequality and the wealth gap, by continuing institutionalized warfare, regime change, threats of military action, and maintaining 800 bases around the world. No one pretends that the foreign policy of the U.S. can or will be radically changed overnight. The hope is there, however, that based on what we see happening in domestic policy, the Biden administration may yet begin to move in a better direction when it comes to foreign affairs. You can start, Mr. President, by not grandstanding against the Russians. That’s so old, and it gets us nowhere. AuthorJohn Wojcik is Editor-in-Chief of People's World. He joined the staff as Labor Editor in May 2007 after working as a union meat cutter in northern New Jersey. There, he served as a shop steward, as a member of a UFCW contract negotiating committee, and as an activist in the union's campaign to win public support for Wal-Mart workers. In the 1970s and '80s he was a political action reporter for the Daily World, this newspaper's predecessor, and was active in electoral politics in Brooklyn, New York. Republished from Peoples World.