|

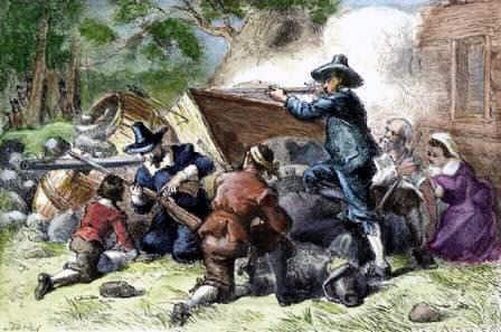

It is generally accepted by most on the ‘left’ that capitalism required the black slave for capital to be “kick-started”,[1] and consequently, that the similarities in the lives of the early black slave and the white indentured servant required the creation of racial differentiation (hierarchical and racist in nature) to prevent Bacon’s Rebellion style class solidarity across racial lines from reoccurring. The capitalist class in the US has been historically successful in creating an atmosphere within the circles of radical labor that excludes solidarity with black liberation and feminist struggles. Yet, the black community historically has been at the forefront of the struggle for socialism in the US. Taking into consideration the history of dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, radical labor in the US has had towards black struggles for liberation, how could it be that the black community has stood in a vanguard position in the struggle for an emancipation that would include those whom they have been excluded by? This paper will look at two occasions in which we can see the exclusion of identity struggles from labor struggles, and answer the riddle of how white labor has been able to identify more with capitalist of their own race than with their fellow nonwhite worker. In connection to this, we will be examining three different perspectives concerning the relationship of the black community’s receptivity and active role in the struggle for socialism and the emancipation of labor. A perfect example of this previously mentioned exclusion of identity from labor can be seen in Jacksonian radical democrats like Orestes Brownson, who although representing a radical emancipatory thought in relation to labor, failed to see how the abolitionist movement should have been included into the cause of the northern workers. Thus, his positions was (before falling into conservatism), that “we can legitimate our own right to freedom only by arguments which prove also the negro’s right to be free”.[2] The question is the negro’s right to be free when? Although he included blacks into the general emancipatory process, he was staunchly against abolitionist as “impractical and out of step with the times”,[3] and eventually urged northern labor to side with the southern plantation owners to counter the force of the northern industrial capitalist. What we see here with Brownson is a dismissal for the abolitionist struggle against black chattel slavery, unless it takes a secondary role to white labor’s struggle for the abolition of wage slavery. Brownson’s central flaw here is his assumption that you can free one while maintaining the other in chains, whereas the reality is that “labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded”[4] In the generation of American radicals that came after Brownson we see a similar dynamic between the 48’ers[5] of the first section of the International and the utopian/feminist radicals of sections nine and twelve. This split takes place between Sorge and the German Marxist and the followers of the ‘radical’ Stephen Andrews and the spiritualist free-love feminist Victoria Woodhull. As Herreshoff states, in relation to the feminist movement of the time, “the Marxists were talking to the feminist the way Brownson had talked to the abolitionist before the Civil War.”[6] By this what is meant is that the struggle for women’s political emancipation, was treated as a sideline issue, that should be dealt with – or automatically solved – only after labor’s emancipation. Now, it could very well be argued that the positions taken by Sorge and some of the other Marxist 48’ers was not ‘Marxist’ at all. Marx and Engels were staunch abolitionist, close followers (and writers) of the Civil War, and even pressured Lincoln greatly towards taking up the cause of emancipation; this puts them in a direct opposition to the positions taken by the northern labor radicals like Brownson[7]. Engels also pronounced himself fully in favor of women’s suffrage as essential in the struggle for socialism[8]. The expansion of this argument cannot be taken up here though. The point is that racial and sexual contradictions within the working masses have played an essential function in maintaining the capitalist structures of power. While workers identify – or are coerced into identifying – workers of other races, ethnicities, or sexes as their enemy, their real enemy – their boss – is either ignored or positively identified with. Thus, white workers can blame their wage cuts/stagnations on the undocumented immigrant. Although he does play a function in maintaining wages low, the one who sets the terms for the function the immigrant is coerced into playing is the capitalist, not the immigrant. There are countless analogies to describe this relation, my favorite perhaps is the one of the cookies. In a table you have 100 cookies, on one side of the table you have the capitalist (usually caricatured as a heavy-set fellow) with 99 cookies to eat for himself. On the other side you have a dirtied white face worker, a dirtied brown face immigrant worker, and finally, the last cookie. The capitalist leans to the white worker and tells him, “be careful, the immigrant will take your cookie”. Here we have the general function of racial division, the motto which is “have the white worker base his identification not in the dirt on his face, but in the mythical face laying under the dirt”. This mythical face under the dirt is the symbolic link of the white worker and the white capitalist. The link of commonality is based on the illusion of the undirtied faced white worker. The dirt, of course, symbolizes the everyday conditions of his toiling existence. Even though the white worker’s everydayness is infinitely more like the immigrant’s (immigrant here is replaceable with black/women/etc.), he is coerced into consenting his identification with whom he has in common no more than one does with a bloodsucking mosquito on a hot summer’s day. Regardless of the dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, of radical labor’s relation to other identity struggles, the black community has been in the forefront of the struggle for socialism in America. Not only have elements of the black community consistently served as the revolutionary vanguard, but the community itself has historically expressed a receptivity of socialism that is unmatched by their white working-class counterparts. There have been a few interesting ways of explaining the phenomenon of the black community’s receptivity of socialist ideas. Edward Wilmont Blyden, sometimes called the father of Pan-Africanism, argued in his text African Life and Customs that the African community is historically communistic. Thus, there is something communistic within the ethos of the black community, that even though it has been generationally separated from its origins, maintains itself in the black experience. He states that the African community produced to satisfy the “needs of life”, held the “land and the water [as] accessible to all. Nobody is in want of either, for work, for food, or for clothing.” The African community had a “communistic or cooperative” social life, where “all work for each, and each work for all.”[9] The argument that a community’s spirit or ethos plays an essential role in its ability to be receptive to socialism is one that is also being analyzed with respect to the “primitive communism” of indigenous communities in South America. Most famously this is seen in Mariategui, who states: “In Indian villages where families are grouped together that have lost the bonds of their ancestral heritage and community work, hardy and stubborn habits of cooperation and solidarity still survive that are the empirical expression of a communist spirit. The “community” is the instrument of this spirit. When expropriations and redistribution seem about to liquidate the “community,” indigenous socialism always finds a way to reject, resist, or evade this incursion.”[10] These arguments have been recently found by Latin American Marxist scholars like Néstor Kohan, Álvaro Garcia Linera, and Enrique Dussel, to have already been present in Marx. From the readings of Marx’s annotations of the anthropological texts of his time (specifically Kovalevsky’s), they argue that Marx began to see the revolutionary potential of the “communards” in their communistic sprit. This was a spirit that staunchly rejected capitalist individualism, leading him to believe that its clash with the expansive nature of capital, if victorious, could be an even quicker path to socialism than a proletarian revolution. Not only would the indigenous community serve as an ally of the proletariat as revolutionary agent, but the communistic spirited community is itself a revolutionary agent too.[11][12] Another way of explaining the phenomenon of a historically white radical labor movement (at least until the founding of CPUSA in 1919), and a historically radical black community[13], is through reference to an interview Angela Davis does from prison when asked a similar question. In this 1972 interview Angela mentions that the black community does not have the “hang ups” the majority of the white community has when they hear the word ‘communism’. She goes on to describe an encounter with a black man who tells her that although he does not know what communism is, “there must be something good about it because otherwise the man wouldn’t be coming down on you so hard.”[14] What we have here is a sort of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. The acceptance of communism is because of the militant rejection my oppressor has towards it. Although it might seem as a ‘simplistic’ conclusion, I assure there is a profound rationality behind it. The rationality is this “if the alternative is not different enough to scare my oppressors shitless, it is not an alternative where my conditions as oppressed will change much.” This logic, simplistic as it might seem, is one the current ‘socialist’ movement in the US is in dire need of re-examining. If the alternatives one is proposing does not bring fright upon those whose heels your necks are under, then what one is proposing is no qualitative alternative at all; rather, it is merely a request to play within the parameters the ruling class gives you. The relationship of who is setting the parameters is not changed by the mere expansion of them. Both of these ways of examining the question concerning the relationship of the black community and its acceptance of socialist ideas I believe hold quite a bit of truth to them. Regardless, I think there is one more way to answer this question. The difference is that in this new way of answering the question, we are threatened with finding the possibility of the question itself being antiquated. The thesis I think is worth examining relates to this previous “mythical link” the white worker can establish with the white capitalist. Unlike the white worker, the black worker has not – at least historically – had the ability to identify with a black capitalist from the reflective position of his ‘undirtied’ face. This is given to the fact that the capitalist class, or even broader, the class of elites or the top 1%, has been almost homogeneously white. Thus, whereas the white worker could be manipulated into identifying with the white capitalist, the white homogeneity of the capitalist class did not have the ripe conditions for working class black folks to be manipulated in the same manner. The question we must ask ourselves now is: in a world of a socially ‘progressive’ bourgeois class, like the one we have today, can this ‘mythic-link’ come into a position of possibly becoming a possibility? With the efforts of racial (and sexual) diversification of the top 1%, can this change the relationship of the black community to radical politics? If we accept the thesis that the link of the black community to radical politics has been a result of not being able to – unlike the white worker – have any identity commonality with their exploiter, then, can we say that in a world of a diversified bourgeois class, the radical ethos of the black community is under threat? Is the black working mass and poor going to fall susceptible to the identity loophole capitalism creates for coercing workers into consenting against their own interest? Or will its historical radical ethos be able to challenge it, and see the black bourgeois as much of an enemy as the white bourgeois? Under a diversified bourgeois class, will Booker T. Washington style black capitalism become hegemonic in the black community? Or will the spirit still be that of Fred Hampton’s famous dictum from his Political Prisoner speech “You don’t fight fire with fire. You fight fire with water. We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity. We’re not gonna fight capitalism with black capitalism We’re gonna fight capitalism with socialism.”? I am unsure, but I think perhaps a totally disjunction-al way of thinking about it is incorrect; as in, the disjunction will not be one the totality of the community is forced to homogeneously choose, but one which fractures the community itself without leaving any side’s perspective hegemonized. Regardless, I think it is up to those who represent the cause of the white and non-white working mass and poor, to go these spaces and assure that masses begin to identify based on class lines (‘class’ not restrictive to the industrial proletariat, but expanded to the totality of the working masses, and beyond that to the lumpen elements whose systemic exclusion, excludes them as well from being exploited subjects of the system). Only in this ‘class’ identity approach can we achieve the unity necessary to solve not just the antagonisms of class that capitalism develops and continuously exacerbates, but also those of race, sex, and climate. This does not mean, like it meant for the 19th century labor radicals, that we exclude non-class struggles to a peripherical position where we give them importance only after the socialist revolution has triumphed. Rather, our commonality of interests in transcending the present society forces us to examine how we can work together, and in doing so, begin to acknowledge and work on the overcoming of our own contradictions with each other. Citations. [1]III, F. B. (2003). The Prison Slave as Hegemony's (Silent) Scandel. In Afro-Pessimism An Introduction (pp. 72). [2] Brownson, O. A. “Slavery-Abolitionism.” Boston Quarterly Review, I (1838), (pp. 240). [3] Herreshoff, D. American Disciples of Marx (Wayne State University Press, 1967), (pp. 39). [4] Marx, K. (1967). Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production (Vol. 1). (F. Engels, Ed.) International Publishers. (pp. 301) [5] “48’ers” refers to the Germans that came after the attempted revolution of 1848 (the one the Communist Manifesto was written for). Having to face persecution, many fled to the US. [6] Ibid. (pp. 82). [7] For more see: Marx, K. & Engels, F. The Civil War in the United States (International Publishers, 2016) [8] For more see: Engels, F. The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (International Publishers, 1975) [9] Blyden, E. W. African Life and Customs (Black Classic Press, 1994) (pp. 10-11) [10] Mariategui, J. C. Seven Essays of Interpretation of Peruvian Reality (1928), (pp. 68) [11] Linera, A. G. (2015) Cuaderno Kovalevsky. In Karl Marx: Escritos Sobre la Comunidad Ancestral [12] This is itself a message that strikes at the heart of the dogmatism of certain Marxist circles. Circles that religiously follow the early unilateral theory of history Marx’s begins proposing in The German Ideology, a view that was used to argue the revolutionary futility of these communities, and the need to ‘proletarianize’ them. This does not mean we throw out Marx’s discovery of the materialist theory of history upon which the unilateral theory of history arises; but rather, that we treat it in a truly materialist manner (as the later Marx does) and realize the ‘five steps’ to communism is materially specific to the studies Marx had done with relation to the European context. With relation to other contexts, new studies must be made through the same materialist methodology. [13] This is not to be taken as a statement of the homogenous radicalism of the black community in America. The influence of Booker T Washington style of black capitalist ideology does historically have a certain influence in the black community. But, when considered in proportion to the white population, the acceptance of socialism – and its vanguard role in struggles – has been much greater in the black community. [14] Marxist, Afro. (2017, June 11) Angela Davis - Why I am a Communist (1972 Interview) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGQCzP-dBvg About the Author:

My name is Carlos and I am a Cuban-American Marxist. I graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Loras College and am currently a graduate student and Teachers Assistant in Philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. My area of specialization is Marxist Philosophy. My current research interest is in the history of American radical thought, and examining how philosophy can play a revolutionary role . I also run the philosophy YouTube channel Tu Esquina Filosofica and organized for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020.

5 Comments

Patricia

12/20/2020 10:35:29 pm

thank you, I really like the approach of this work. very good

Reply

John1421

12/20/2020 10:39:06 pm

good help for my class work thanks

Reply

timmy shaner

1/4/2021 12:56:24 am

very interesting take. i have heard anecdotes of people denying racism in america by citing a prominent black actor’s view on racism calling it, “ a good excuse for not getting there.” It does seem like a potential mythic-link.

Reply

Charles Brown

1/9/2022 08:20:03 pm

“ Labor in white in white skin will not be free while labor in black skin is branded -Karl Marx

Reply

Charles Brown

1/9/2022 08:31:38 pm

President Lyndon B. Johnson once said, "If you can convince the lowest white man he's better than the best colored man, he won't notice you're picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he'll empty his pockets for you."

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed