|

Who, or what, is the “middle class”? Most people identify themselves as middle class, but what does that mean, and what difference does it make? This article’s first focus is on the concept of middle class, especially the way people understand it and use it, from the perspectives of those who answer survey questions to the analysts who study social inequality. The way “class” is defined and used has the effect of rendering some social processes invisible. Second, Marxist analysis offers a much different conception of class, one that brings to light social dynamics hidden in the bourgeois perspective. Third, what are the material conditions and consciousness of the U.S. “middle class” today, and what are the political pressures that are bearing down on different segments of the economy? Economists, pollsters, and many policy researchers define class with reference simply to individuals’ or households’ annual income. For example, the Pew Research Center arrays all income data points in a line, from lowest to highest. The very middle point is the median. Then, people with incomes of less than two-thirds of the median are labeled “lower income.” “Upper income” are those with incomes twice the median or more. All those in-between are “middle income” or “middle class.” The advantage of this technique is that it offers a specific measure that can be used to compare inequality across time and place, data which the Pew Research Center regularly reports. The disadvantage is that it hides the impact of a host of other factors determining one’s relative position in the economy, like wealth and social status. And, unlike a Marxist analysis, this view of class, with its more or less arbitrary boundaries, doesn’t recognize that classes are collectivities that have a social reality over and above their individual members, and that act more effectively for social change than any individual member could possibly act. Some use the term “middle class” simply to distinguish it from those with the least income, who become known collectively as “the poor.” Reverend William Barber of the Poor People’s Campaign, for example, criticized the Democratic Party’s sole focus on the middle class, which he contrasted with the interests of the poor, as he said about poverty at a recent online meeting: “Neoliberalism isn’t going to fix this. The middle class isn’t going to fix this. And as Pope Francis has said, trickle-down has failed us.” Sociologist Mary Pattillo, in her 2005 study of “Black Middle-Class Neighborhoods” in the Annual Review of Sociology, writes that defining the middle class is difficult and that her article might better be entitled “Black Non-Poor Neighborhoods.” Trade union discourse tends to rely on the term to describe the benefits of good union jobs. Columbus Ohio building trade union activist Dorsey Hagar, for example, says that union jobs get workers “on that direct path to the middle class where they’re providing for themselves and their family.” Besides income, some people understand “middle class standing” as a social status, like occupational prestige and years of education. Sociologists today define the middle class as an ever-changing assortment of different occupational groups in “a heterogeneous and historically shifting middle class rather than distinct entities.”1 Others define middle class by levels of consumption, such as aspirations for home ownership, children’s education, health insurance and economic security, as in a 2010 Commerce Department document prepared for then Vice-President Joe Biden. If being middle class were just a matter of self-perception, almost all Americans would be in the middle class, according to one 2015 survey, which found that well over 85% call themselves middle class. Racial identification matters too; whites are far more likely to define themselves as middle class than are African Americans with similar incomes. In Marxist analysis, the understanding of “class” is very different. It starts by looking at large-scale social processes, and finds the basis of social classes in the relations of production in the economy. Those who own and control the means of production, and who are able to take ownership of all that is produced, form the ruling class; in capitalist society the ruling class is the bourgeoisie, while in feudal society, it was the landed aristocracy. Those who sell their labor power to the owners of the means of production are the proletariat or working class. Instead of class as a characteristic of individuals, Marxist analysis studies the way classes act in society as collective actors. Struggle between classes is the “motor of history,” driving all social change. Classes are rooted in the common material interests that derive from a similar relationship to the means of production. But that is not enough to unite or empower a class. To be a class “for itself” as well as “in itself,” a class needs a “community, . . . national bond, and . . . political organization,” as Marx said in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte. The small-holding French peasants he studied had common material interests, but they lived apart from one another and were unaware of those commonalities. They were just, in Marx’s words, “the simple addition of homologous magnitudes, much as potatoes in a sack form a sack of potatoes.” As a class, the peasantry was only as powerful as the sum of its parts. A class’s real power, over and above the sum of its members, is derived not just from common material interests, but from the class’s awareness of itself as a class engaged in struggle with other classes. That class consciousness was what empowered the industrialists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to defeat the landed aristocracy, and it will be what empowers the proletariat to defeat the capitalist ruling class. Historical materialism predicts that society will become more and more polarized into two great classes, in conflict with each other. But other classes exist simultaneously. Some are vestiges of earlier stages of class relations, like the remnants of the landed aristocracy. Marx recognized that throughout history there are strata in society that are between the two great classes. New technologies may bring changes in class relations that hasten the demise of the old system. One of these “middle” classes for Marx was the occupational group of merchants who emerged from the separation of production and commerce at the dawn of the industrial age. When the Pew Research Center or the New York Times refers to the “middle class,” they are referring to a sector of the working class. Roberta Wood in her pamphlet “Marxism in the Age of Uber” has an expansive vision of the working class as 90 percent of the U.S. population: “The working class of the 21st century includes rideshare drivers, nursing home aides, baristas, warehouse workers, UPS package handlers, teachers, engineers, research scientists, and I.T. folks — alongside factory, construction and farmworkers and incarcerated labor.” Even before the pandemic, the non-poor working class was being squeezed financially. “The costs of housing, health care and education are consuming ever larger shares of household budgets, and have risen faster than incomes,” according to a 2019 article in the New York Times. “Today’s middle-class families are working longer, managing new kinds of stress and shouldering greater financial risks than previous generations did.” Then, the pandemic economy hit. The effects of loss of jobs and income have been severe and will reverberate for years to come. Working families face food insecurity, utility shut-offs, loss of health insurance, and eviction. According to a Pew Research Survey, about a quarter of all adults in the U.S., and one in every three low-wage workers, lost their jobs. More women than men, and especially Black and Latinx women, report having trouble paying their bills, and are more likely than men to have borrowed money, used savings that had been set aside for retirement, and gotten food from a food bank. Small business owners, the petty bourgeoisie in Marxist terms, is seen as a “middle” class, torn in their loyalty to the working class, which is closest to it in material conditions, or to the ruling class, to which it improbably aspires. Owners of small businesses and independent professionals may employ a handful of individual workers, whom they exploit by appropriating the surplus value of their labor in the same way that big corporations exploit workers. In the U.S., this sector is very engaged politically; one study found that 98% of small business owners were registered to vote and 62% have contributed to campaigns. A survey from before the pandemic showed that a majority of small business owners benefited from the 2017 tax cuts and believed that their businesses would be better off if Trump were re-elected. Some members of this group endorse the extreme right. As C. J. Atkins pointed out, the Atlantic documented that the insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol on January 6 were “a cavalry made up of ‘business owners, CEOs, state legislators, police officers, active and retired members of the military, real-estate brokers,’ and others.” An article in the Washington Post revealed that almost 60% of those charged in the Capitol insurrection “showed signs of prior money troubles, including bankruptcies, notices of eviction or foreclosure, bad debts, or unpaid taxes over the past two decades.” Downward mobility no doubt fueled their anger. But this sector is still powerless compared to big business. Like the working class, it is vulnerable to the vagaries of the capitalist economy of boom and bust. Small business owners were hit hard in the current recession. In September 2020 it was estimated that 100,000 small businesses that had shut down due to the pandemic had closed permanently. Black-owned businesses closed at twice the rate of white-owned businesses. That was even before the autumn surge in cases and further lockdowns. These times remind me of the saying, “Every woman is six weeks away from welfare.” It recognized the vulnerability of working women in particular, who often had sole responsibility for their children as well as themselves. Even if comfortably situated today, lulled by the idea that they had joined the middle class, job losses or medical emergencies could quickly drive people into poverty. Only the ruling class is protected. Notes 1. Melanie Archer and Judith Blau, “Class Formation in Nineteenth-Century America: The Case of the Middle Class,” Annual Review of Sociology, 1993, vol. 19, no. 1. Images: top, Christopher Chappelear (CC BY 2.0); college graduate, COD Newsroom (CC BY 2.0); barista, Phil Squires (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); closed business, Ivan Radic (CC BY 2.0). AuthorAnita Waters is Professor Emerita of sociology at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, and an organizer for the CPUSA in Ohio. This article was first published by CPUSA. Archives May 2021

0 Comments

In the wake of the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent protests and calls for change that followed, an interesting solution was brought up and encouraged, the call to buy from black businesses. While black businesses are indeed a way to grow wealth for the black community, they are in no way a solution to the broader source of oppression. In order to truly liberate the black community from the chains of racism, generational poverty, state oppression, and exploitation, it’s not enough to encourage the entrepreneurship of only a few people, one must address it from a collective and anti-capitalist approach. Only with socialism will the black community truly be eliminated from the systemic racism capitalism has weighed over them. When speaking about black entrepreneurship one is often met with rosy words of praise, all across the political spectrum, even so called “progressives” and “intersectional feminists” gush at the idea of buying from black owned businesses (BOBs). But let us not be fooled, small businesses are not inherently better than corporate behemoths. In fact, small businesses can and usually are worse for workers than larger businesses, including conditions such as offering worse benefits, lower wages, and being exempt from worker protections. This isn’t a defense of big business but a criticism of businesses overall. Small businesses and mega-corporations both exploit their workers. However, small businesses, unlike mega-corps, have a quaint rosy glow which excuses them from the harsh scrutiny received from larger companies. It doesn’t matter who’s in charge of the business or if the company is large or small. Businesses functioning in the traditional structure are still exploitative; the worker continues to not receive the full value of their labor and are forced to rely on the will and the mercy of the boss to not starve. Moving on, the origins of black capitalism and the related “opportunity zones” have been a meager scrap thrown to the black community in a lame effort to eliminate the effects of systemic racism and generational poverty. The origins of modern Black capitalism lay in Nixon’s “Southern Strategy”. Instead of actual racial and economic justice such as desegregation, more public sector jobs, anti-discrimination measures, etc., mild tax incentives and breaks was the solution to racial ghettos and oppression. These meager crumbs tossed to the black community allowed Nixon to oppose vital economic reforms championed by Civil Rights activists and to crack down on the black community in other ways (most notably the War on Drugs and the War on Crime). In an effort to undermine important economic and racial reforms Nixon started spouting free-market and libertarian talking points, arguing that capitalism was the natural cure of racial ghettos and that black people should “help themselves.” Such rhetoric appears in his Acceptance of the Republican Nomination for President Speech “Instead of Government jobs and Government housing and Government welfare, let Government use its tax and credit policies to enlist in this battle the greatest engine of progress ever developed in the history of man-American private enterprise.” Black-Americans were thus wished good-luck before being shoved down the meat grinder that is capitalism, often put in a position where they are the ones worse off after every financial crisis and capable of gleaning only the tiniest bits during the good times (especially in comparison to their white counterparts). Decades have passed since the Nixon administration and both parties have continued to champion black capitalism while either cutting social programs or giving very meager assistance. Black capitalism, while it may have started with Nixon, eventually morphed to “enterprise zones” under Reagan, “new market tax policies” with Clinton, and “promise zones” by Obama. All of whom have continued and put into place brutal neoliberal policies where BIPOC typically bear the heaviest burden and draconian treatment of felons, especially those on drug charges (which are disproportionately black), creating a cycle of poverty for generations to come. The problems that plague the black community are not a lack of entrepreneurship or an insufficiency of capitalism, rather, it is capitalism itself that continues to dig the black community into an even deeper hole. It was “entrepreneurs” and banks run by capitalists who were responsible for shoving subprime mortgages down the throats of black borrowers, resulting in 53% of all wealth in the black community being wiped out, and by 2009 35% of black communities having zero or negative wealth. It is years of mass incarceration, housing discrimination, and red-lining which pushed and continue to keep the black community in poverty. None of the problems listed above can be attributed to the problem of a lack of “black entrepreneurship” or lack of capitalism. Rather, it is capitalism that is at the root of many of these problems. It was land developers and planners who decided to red-line neighborhoods in fear that having integrated neighborhoods would decrease the value of the neighborhoods, and thereby lower their profits. It was the private prison companies who lobbied the government for harsher and more draconian laws and sentencing to funnel more BIPOC into the prison system, which further ruined their chances of building any wealth, and thus made it more likely that they would return to prison – not to forget of course the many companies that rely on and use prisoners as free labor. Minority capitalism isn’t the solution to wider systemic problems caused by the capitalist system itself. The assumption of black capitalism is that it is possible for society – and especially Black Americans – to buy their way out of racism and oppression. This is an assumption that is verifiably false. It is a bandage upon an internal wound. It is neoliberalism’s way of co-opting an important movement and, like a leech, sucking out all the meaning of the movement. Additionally, “buying black” and supporting black capitalism is an incredibly individualistic approach to uplifting the black community. Black capitalism, as well intentioned as it seems, only uplifts a few members of the black community. True liberation is not adding a few members of the marginalized group to the oppressing group, rather, it is dismantling the system that creates thus conditions. Black capitalism lifts a few members of the community to the position of the bourgeoisie. Having a more diverse bourgeoisie, a more diverse group of people responsible for the suppression of the proletariat does nothing for the vast majority of people who face hunger, starvation, homelessness, poverty, and various other issues that intersect with their identity. The only solution is the dismantle of capitalism. What are examples then of anti-capitalist societies that have managed to drastically eliminate the legacy of systemic racism? The answer to that is Cuba. Cuba prior to the revolution used to be no different than the US when it came to race relations. Afro-Cubans faced widespread discrimination and segregation. They were given the worst jobs, housing, and education (if any at all). However, immediately after the revolution the newly established government set to work immediately to combat all traces of systemic racism. Anti-racist measures were enforced both legally and socially. In Cuba’s Constitution Chapter 1 Article 42 all people regardless of their identity(ies) are guaranteed equality before the law, in comparison to the US Constitution where such an explicit promotion of equality doesn’t exist. Furthermore, anti-discrimination doesn’t only exist as an empty statute but is constantly and vigorously enforced with militias in any location where black and mestizos could be denied equal treatment. A harsh contrast in comparison to the US where BIPOC are constantly being denied mortgage loans and/or given worse rates, poorer medical care, and denied jobs because of their race. While there’s no doubt that fully eradicating the legacy of systemic racism won’t be solved overnight and people will still hold onto many of their discriminatory beliefs even under a different economic system, in the transcendence of capitalism, the economic and material conditions that produce racial inequality and oppression will be abolished, a vital and necessary step to doing away with racism. Citations Baradaran, Mehrsa. Opinion | The Real Roots of ‘Black Capitalism’ (Published 2019). 1 Apr. 2019, nytimes.com/2019/03/31/opinion/nixon-capitalism-blacks.html. Barnes, Jack. “The Militant - April 19, 2010 -- Affirmative Action Needed to Unite Toilers.” The Militant, 19 Apr. 2010, themilitant.com/2010/7415/741560.html. Coleman, Aaron Ross. “Black Capitalism Won’t Save Us.” The Nation, 24 May 2019, thenation.com/article/archive/nipsey-killer-mike-race-economics/. “Cuba’s Constitution of 2019.” Constitute Project, 4 Feb. 2020, constituteproject.org/constitution/Cuba_2019.pdf?lang=en. Mallett, Kandist. “The Black Elite Are an Obstacle Toward Black Liberation.” Teen Vogue, 30 Oct. 2020, teenvogue.com/story/black-elite-racial-justice. Martinez, Carlos. “20 Reasons to Support Cuba - Invent the Future.” Invent the Future, 13 Jan. 2014, invent-the-future.org/2013/07/20-reasons-to-support-cuba/. Prescod, Paul. “‘Black Capitalism’ From Richard Nixon to Joe Biden.” Jacobin, 18 May 2020, jacobinmag.com/2020/05/black-capitalism-joe-biden-unions-class. “Speeches by Richard M. Nixon: Acceptance of the Republican Nomination for President.” US Embassy, 8 Aug. 1968, usa.usembassy.de/etexts/speeches/rhetoric/rmnaccep.htm. About the Author:

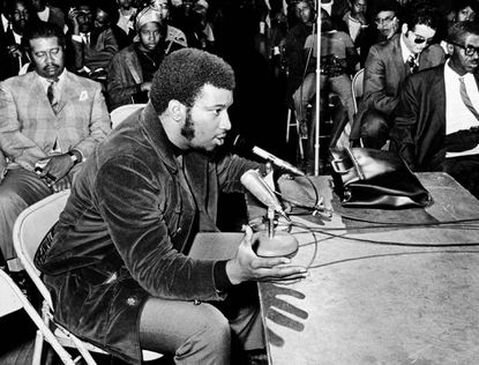

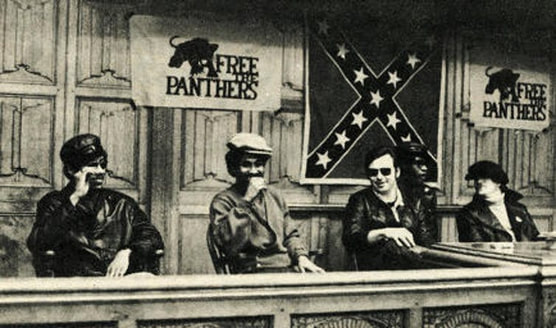

N.C. Cai is a Chinese American Marxist Feminist. She is interested in socialist feminism, Western imperialism, history, and domestic policy, specifically in regards to drug laws, reproductive justice, and healthcare. It is generally accepted by most on the ‘left’ that capitalism required the black slave for capital to be “kick-started”,[1] and consequently, that the similarities in the lives of the early black slave and the white indentured servant required the creation of racial differentiation (hierarchical and racist in nature) to prevent Bacon’s Rebellion style class solidarity across racial lines from reoccurring. The capitalist class in the US has been historically successful in creating an atmosphere within the circles of radical labor that excludes solidarity with black liberation and feminist struggles. Yet, the black community historically has been at the forefront of the struggle for socialism in the US. Taking into consideration the history of dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, radical labor in the US has had towards black struggles for liberation, how could it be that the black community has stood in a vanguard position in the struggle for an emancipation that would include those whom they have been excluded by? This paper will look at two occasions in which we can see the exclusion of identity struggles from labor struggles, and answer the riddle of how white labor has been able to identify more with capitalist of their own race than with their fellow nonwhite worker. In connection to this, we will be examining three different perspectives concerning the relationship of the black community’s receptivity and active role in the struggle for socialism and the emancipation of labor. A perfect example of this previously mentioned exclusion of identity from labor can be seen in Jacksonian radical democrats like Orestes Brownson, who although representing a radical emancipatory thought in relation to labor, failed to see how the abolitionist movement should have been included into the cause of the northern workers. Thus, his positions was (before falling into conservatism), that “we can legitimate our own right to freedom only by arguments which prove also the negro’s right to be free”.[2] The question is the negro’s right to be free when? Although he included blacks into the general emancipatory process, he was staunchly against abolitionist as “impractical and out of step with the times”,[3] and eventually urged northern labor to side with the southern plantation owners to counter the force of the northern industrial capitalist. What we see here with Brownson is a dismissal for the abolitionist struggle against black chattel slavery, unless it takes a secondary role to white labor’s struggle for the abolition of wage slavery. Brownson’s central flaw here is his assumption that you can free one while maintaining the other in chains, whereas the reality is that “labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded”[4] In the generation of American radicals that came after Brownson we see a similar dynamic between the 48’ers[5] of the first section of the International and the utopian/feminist radicals of sections nine and twelve. This split takes place between Sorge and the German Marxist and the followers of the ‘radical’ Stephen Andrews and the spiritualist free-love feminist Victoria Woodhull. As Herreshoff states, in relation to the feminist movement of the time, “the Marxists were talking to the feminist the way Brownson had talked to the abolitionist before the Civil War.”[6] By this what is meant is that the struggle for women’s political emancipation, was treated as a sideline issue, that should be dealt with – or automatically solved – only after labor’s emancipation. Now, it could very well be argued that the positions taken by Sorge and some of the other Marxist 48’ers was not ‘Marxist’ at all. Marx and Engels were staunch abolitionist, close followers (and writers) of the Civil War, and even pressured Lincoln greatly towards taking up the cause of emancipation; this puts them in a direct opposition to the positions taken by the northern labor radicals like Brownson[7]. Engels also pronounced himself fully in favor of women’s suffrage as essential in the struggle for socialism[8]. The expansion of this argument cannot be taken up here though. The point is that racial and sexual contradictions within the working masses have played an essential function in maintaining the capitalist structures of power. While workers identify – or are coerced into identifying – workers of other races, ethnicities, or sexes as their enemy, their real enemy – their boss – is either ignored or positively identified with. Thus, white workers can blame their wage cuts/stagnations on the undocumented immigrant. Although he does play a function in maintaining wages low, the one who sets the terms for the function the immigrant is coerced into playing is the capitalist, not the immigrant. There are countless analogies to describe this relation, my favorite perhaps is the one of the cookies. In a table you have 100 cookies, on one side of the table you have the capitalist (usually caricatured as a heavy-set fellow) with 99 cookies to eat for himself. On the other side you have a dirtied white face worker, a dirtied brown face immigrant worker, and finally, the last cookie. The capitalist leans to the white worker and tells him, “be careful, the immigrant will take your cookie”. Here we have the general function of racial division, the motto which is “have the white worker base his identification not in the dirt on his face, but in the mythical face laying under the dirt”. This mythical face under the dirt is the symbolic link of the white worker and the white capitalist. The link of commonality is based on the illusion of the undirtied faced white worker. The dirt, of course, symbolizes the everyday conditions of his toiling existence. Even though the white worker’s everydayness is infinitely more like the immigrant’s (immigrant here is replaceable with black/women/etc.), he is coerced into consenting his identification with whom he has in common no more than one does with a bloodsucking mosquito on a hot summer’s day. Regardless of the dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, of radical labor’s relation to other identity struggles, the black community has been in the forefront of the struggle for socialism in America. Not only have elements of the black community consistently served as the revolutionary vanguard, but the community itself has historically expressed a receptivity of socialism that is unmatched by their white working-class counterparts. There have been a few interesting ways of explaining the phenomenon of the black community’s receptivity of socialist ideas. Edward Wilmont Blyden, sometimes called the father of Pan-Africanism, argued in his text African Life and Customs that the African community is historically communistic. Thus, there is something communistic within the ethos of the black community, that even though it has been generationally separated from its origins, maintains itself in the black experience. He states that the African community produced to satisfy the “needs of life”, held the “land and the water [as] accessible to all. Nobody is in want of either, for work, for food, or for clothing.” The African community had a “communistic or cooperative” social life, where “all work for each, and each work for all.”[9] The argument that a community’s spirit or ethos plays an essential role in its ability to be receptive to socialism is one that is also being analyzed with respect to the “primitive communism” of indigenous communities in South America. Most famously this is seen in Mariategui, who states: “In Indian villages where families are grouped together that have lost the bonds of their ancestral heritage and community work, hardy and stubborn habits of cooperation and solidarity still survive that are the empirical expression of a communist spirit. The “community” is the instrument of this spirit. When expropriations and redistribution seem about to liquidate the “community,” indigenous socialism always finds a way to reject, resist, or evade this incursion.”[10] These arguments have been recently found by Latin American Marxist scholars like Néstor Kohan, Álvaro Garcia Linera, and Enrique Dussel, to have already been present in Marx. From the readings of Marx’s annotations of the anthropological texts of his time (specifically Kovalevsky’s), they argue that Marx began to see the revolutionary potential of the “communards” in their communistic sprit. This was a spirit that staunchly rejected capitalist individualism, leading him to believe that its clash with the expansive nature of capital, if victorious, could be an even quicker path to socialism than a proletarian revolution. Not only would the indigenous community serve as an ally of the proletariat as revolutionary agent, but the communistic spirited community is itself a revolutionary agent too.[11][12] Another way of explaining the phenomenon of a historically white radical labor movement (at least until the founding of CPUSA in 1919), and a historically radical black community[13], is through reference to an interview Angela Davis does from prison when asked a similar question. In this 1972 interview Angela mentions that the black community does not have the “hang ups” the majority of the white community has when they hear the word ‘communism’. She goes on to describe an encounter with a black man who tells her that although he does not know what communism is, “there must be something good about it because otherwise the man wouldn’t be coming down on you so hard.”[14] What we have here is a sort of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. The acceptance of communism is because of the militant rejection my oppressor has towards it. Although it might seem as a ‘simplistic’ conclusion, I assure there is a profound rationality behind it. The rationality is this “if the alternative is not different enough to scare my oppressors shitless, it is not an alternative where my conditions as oppressed will change much.” This logic, simplistic as it might seem, is one the current ‘socialist’ movement in the US is in dire need of re-examining. If the alternatives one is proposing does not bring fright upon those whose heels your necks are under, then what one is proposing is no qualitative alternative at all; rather, it is merely a request to play within the parameters the ruling class gives you. The relationship of who is setting the parameters is not changed by the mere expansion of them. Both of these ways of examining the question concerning the relationship of the black community and its acceptance of socialist ideas I believe hold quite a bit of truth to them. Regardless, I think there is one more way to answer this question. The difference is that in this new way of answering the question, we are threatened with finding the possibility of the question itself being antiquated. The thesis I think is worth examining relates to this previous “mythical link” the white worker can establish with the white capitalist. Unlike the white worker, the black worker has not – at least historically – had the ability to identify with a black capitalist from the reflective position of his ‘undirtied’ face. This is given to the fact that the capitalist class, or even broader, the class of elites or the top 1%, has been almost homogeneously white. Thus, whereas the white worker could be manipulated into identifying with the white capitalist, the white homogeneity of the capitalist class did not have the ripe conditions for working class black folks to be manipulated in the same manner. The question we must ask ourselves now is: in a world of a socially ‘progressive’ bourgeois class, like the one we have today, can this ‘mythic-link’ come into a position of possibly becoming a possibility? With the efforts of racial (and sexual) diversification of the top 1%, can this change the relationship of the black community to radical politics? If we accept the thesis that the link of the black community to radical politics has been a result of not being able to – unlike the white worker – have any identity commonality with their exploiter, then, can we say that in a world of a diversified bourgeois class, the radical ethos of the black community is under threat? Is the black working mass and poor going to fall susceptible to the identity loophole capitalism creates for coercing workers into consenting against their own interest? Or will its historical radical ethos be able to challenge it, and see the black bourgeois as much of an enemy as the white bourgeois? Under a diversified bourgeois class, will Booker T. Washington style black capitalism become hegemonic in the black community? Or will the spirit still be that of Fred Hampton’s famous dictum from his Political Prisoner speech “You don’t fight fire with fire. You fight fire with water. We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity. We’re not gonna fight capitalism with black capitalism We’re gonna fight capitalism with socialism.”? I am unsure, but I think perhaps a totally disjunction-al way of thinking about it is incorrect; as in, the disjunction will not be one the totality of the community is forced to homogeneously choose, but one which fractures the community itself without leaving any side’s perspective hegemonized. Regardless, I think it is up to those who represent the cause of the white and non-white working mass and poor, to go these spaces and assure that masses begin to identify based on class lines (‘class’ not restrictive to the industrial proletariat, but expanded to the totality of the working masses, and beyond that to the lumpen elements whose systemic exclusion, excludes them as well from being exploited subjects of the system). Only in this ‘class’ identity approach can we achieve the unity necessary to solve not just the antagonisms of class that capitalism develops and continuously exacerbates, but also those of race, sex, and climate. This does not mean, like it meant for the 19th century labor radicals, that we exclude non-class struggles to a peripherical position where we give them importance only after the socialist revolution has triumphed. Rather, our commonality of interests in transcending the present society forces us to examine how we can work together, and in doing so, begin to acknowledge and work on the overcoming of our own contradictions with each other. Citations. [1]III, F. B. (2003). The Prison Slave as Hegemony's (Silent) Scandel. In Afro-Pessimism An Introduction (pp. 72). [2] Brownson, O. A. “Slavery-Abolitionism.” Boston Quarterly Review, I (1838), (pp. 240). [3] Herreshoff, D. American Disciples of Marx (Wayne State University Press, 1967), (pp. 39). [4] Marx, K. (1967). Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production (Vol. 1). (F. Engels, Ed.) International Publishers. (pp. 301) [5] “48’ers” refers to the Germans that came after the attempted revolution of 1848 (the one the Communist Manifesto was written for). Having to face persecution, many fled to the US. [6] Ibid. (pp. 82). [7] For more see: Marx, K. & Engels, F. The Civil War in the United States (International Publishers, 2016) [8] For more see: Engels, F. The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (International Publishers, 1975) [9] Blyden, E. W. African Life and Customs (Black Classic Press, 1994) (pp. 10-11) [10] Mariategui, J. C. Seven Essays of Interpretation of Peruvian Reality (1928), (pp. 68) [11] Linera, A. G. (2015) Cuaderno Kovalevsky. In Karl Marx: Escritos Sobre la Comunidad Ancestral [12] This is itself a message that strikes at the heart of the dogmatism of certain Marxist circles. Circles that religiously follow the early unilateral theory of history Marx’s begins proposing in The German Ideology, a view that was used to argue the revolutionary futility of these communities, and the need to ‘proletarianize’ them. This does not mean we throw out Marx’s discovery of the materialist theory of history upon which the unilateral theory of history arises; but rather, that we treat it in a truly materialist manner (as the later Marx does) and realize the ‘five steps’ to communism is materially specific to the studies Marx had done with relation to the European context. With relation to other contexts, new studies must be made through the same materialist methodology. [13] This is not to be taken as a statement of the homogenous radicalism of the black community in America. The influence of Booker T Washington style of black capitalist ideology does historically have a certain influence in the black community. But, when considered in proportion to the white population, the acceptance of socialism – and its vanguard role in struggles – has been much greater in the black community. [14] Marxist, Afro. (2017, June 11) Angela Davis - Why I am a Communist (1972 Interview) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGQCzP-dBvg About the Author:

My name is Carlos and I am a Cuban-American Marxist. I graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Loras College and am currently a graduate student and Teachers Assistant in Philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. My area of specialization is Marxist Philosophy. My current research interest is in the history of American radical thought, and examining how philosophy can play a revolutionary role . I also run the philosophy YouTube channel Tu Esquina Filosofica and organized for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. “Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much higher consideration.” This past 3rd of November the interest of capitalist class wasn’t just assured a win in the presidential election, but it also took a big win in California with the passing of Proposition 22. Proposition 22 was a ballot proposal to maintain the gig economy workers of companies like Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Postmates, etc. under the status of ‘Independent Contractors’. A vote ‘yes’ would mean that the workers in these sectors would remain categorized as independent contractors, a vote ‘no’ would force these app-based gig companies to provide “basic protections to their workers”[1]. After outspending the opposition 12 to 1 by pouring more than 200 million[2] on the ballot initiative, gig economy companies like Uber, Lyft, and more, won. The opposition to the bill was led by various labor organization, but at the head of it was the California Labor Federation (CLF). CLF understood that the passing of this bill meant boosting profits for these gig companies by “denying their drivers’ right to a minimum wage, paid sick leave and safety protections.”[3] Companies like Lyft advertised that the passing of prop 22 meant that workers in these industries would maintain their ‘flexibility’, and fearmongered by stating that up to 90% of drivers could lose their jobs if the bill did not go through. They also mentioned that a vote yes would give drivers “more benefits”, of course, without mentioning that the extra ‘benefits’ they would get are still nowhere near what they would be required to give them if they were considered as workers and not independent contractors.[4] To urge a ‘yes’ vote, these companies went as far as showing videos of single moms saying they wouldn't be able to figure out how to make extra money for their family[5] if the bill didn’t pass. This massive influx of advertisement money was what caused a vote that was polling in at 38% six weeks before its election, to rise 19 points and win.[6] While these gig economy app based companies have grown to be worth billions of dollars, the employees whose labor their growth has depended on have been partaking in worldwide protest because of their poverty wages.[7] Taking this into consideration, and the fact that only 38% was in favor of the bill just six weeks before the vote, it is fair to say that the bill passed because more than $200 million was spent propagandizing people in favor of it. A nice exemplar of how our American Democracy works. The core of the $200 million that was spent was aimed at convincing folks that this was the route that would prove to be the most beneficial for workers. Although not all working families fell for this, the outcome demonstrates quite a few did. The wealth of the owning class proved to be a sufficient engine for the ideologically coercing of workers into consenting against their own interests. What we have here is not the usual schematics of a working class who participates in electoral processes whereby both candidates represent the interest of their enemies; but a working class that when confronted with a clear dichotomous decision of advancing or regressing their interest as a class, was conditioned enough to overwhelmingly vote against their own interest. These ideological tactics of coercing workers into consenting against their own interest are not new. In the days of child labor, the arguments for its maintenance usually presented the same form of cynical concern for workers and their families, stating that families would be unable to survive without the children contributing, and using analogies of child labor at the farm[8] to naturalize and thus legitimate the continuation of such bruteness as having kids under 10 years old lose limbs or die working 10-12 hours a day for miserable wages.[9] In terms of relations of power between labor and capital, the neoliberal capitalism we see today is perhaps closer to the conditions in the time of Mother Jones, than it was after the second world war. Although child labor is not around, the hard-fought victories by unions and communists for workers are constantly attacked and defeated. The last four decades of neoliberal capitalism has been a continuous disempowerment of workers through the cutting of benefits, stagnating of wages, and repression of unionization efforts. The gig economy takes this even further, through an employer’s complete removal of responsibility for workers. By categorizing workers as ‘independent contractors’, the ‘flexibility’ they continuously speak of is one that is only for them. Flexibility for the capitalist entails the removal of responsibilities for his workers, and subsequently, increasing profits for him. But for the worker - regardless of how much the capitalist’s propaganda says they are now ‘flexible’ and ‘free’ – flexibility means insecurity, less pay, and less benefits. Like in sex, flexibility for the worker here only means he can get screwed more efficiently. The passing of this bill in California entails that it will probably be the first domino in many to come. Soon, our working class will face an instability that has not been seen in the last two centuries. The question we must ask ourselves is not just 'what are we doing to prevent this?'; for this question takes a necessarily defensive approach. If we are only defending, although we might win some battles and lose others, those wins are not steps forward, but the prevention of backward steps. This puts us in a pickle between maintaining our position or taking steps backwards. Unlike in sports, were defense is the best form of offense, in the struggles of labor and capital offense is the best form of defense. We must be ready to counter the barbarities that neoliberal capitalism is taking us towards. This is something that cannot be done if our efforts are limited to protecting previous gains, we must be ready to affirm a socialist tomorrow. Our situation is at a crossroad, now more than ever does Luxemburg’s famous dictum ring true, it’s either “socialism or barbarism”. Citations [1] “What is Prop 22, the Uber/Lyft Ballot Measure?,” California Labor Federation, https://calaborfed.org/no-on-prop-22-faq/ [2] Sarah Jones, “Uber and Lyft’s Proposition 22 Win Is a Warning Shot to Democrats,” Intelligencer, last modified November 4, 2020, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/11/uber-lyfts-proposition-22-was-a-warning-shot-to-democrats.html#:~:text=In%20the%20weeks%20leading%20up%20to%20November%203%2C,of%20the%20measure%20regularly%20featured%20people%20of%20color. [3] “What is Prop 22, the Uber/Lyft Ballot Measure?,” California Labor Federation, [4] “What is Prop 22 | California Drivers | Vote YES on Prop 22 | Rideshare | Benefits | Lyft,” Lyft, October 8, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7QJLgdQaf4 [5] Suhauna Hussain, Johana Bhuiyan, Ryan Menezes, “Prop. 22: Here's how your L.A. neighborhood voted on the gig worker measure,” Yahoo!Finance, last modified November 13, 2020, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/uber-lyft-persuaded-california-vote-140036656.html [6] Ibid. [7] Keith Griffith, “Uber drivers around the world go on strike to protest 'poverty wages' as the company prepares to go public at a valuation of $91billion” Daily Mail, last modified May 8, 2019, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7006975/Uber-drivers-world-strike-protest-low-wages.html [8] Bill Kauffman, “The Child Labor Amendment Debate of the 1920's” The Journal of Libertarian Studies, last modified January 29, 2018, https://mises.org/library/child-labor-amendment-debate-1920s-0 [9] Mother Jones, “Civilization in Southern Mills” Industrial Workers of the World Historical Archives, March 1901, https://archive.iww.org/history/library/MotherJones/civilization_in_southern_mills/ About the Author:

My name is Carlos and I am a Cuban-American Marxist. I graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Loras College and am currently a graduate student and Teachers Assistant in Philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. My area of specialization is Marxist Philosophy. My current research interest is in the history of American radical thought, and examining how philosophy can play a revolutionary role . I also run the philosophy YouTube channel Tu Esquina Filosofica and organized for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. During the COVID-19 pandemic, workers’ rights have returned to popular discourse because of mass reliance on frontline workers. As millions of those workers have been scraping by and fearing for their futures, the wealth gap has widened, yet workers are largely expected to go on as normal—show up to work and continue to create a profit for someone at the top, often with no hazard pay. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which has been a COVID-19 hotspot, a union only several years old has taken bold action to unite people in their demands for better working standards and fair wages. Before the pandemic hit, the union won a major contract with the Bucks, which granted a $15 minimum wage by July. Now, Milwaukee Area Service and Hospitality Workers, better known as MASH, is bringing people together to vote. On the morning of Saturday, October 24th, MASH held an early voting rally at the Fiserv Forum (the new Bucks arena) for service and hospitality workers. Workers themselves gave impassioned speeches before going as a group to vote early at MATC. MASH president Peter Rickman started the rally with an announcement that one person who planned to make a speech was not able to make it because her car broke down on the way. Rickman cited the situation as an example of common obstacles the working class faces. “I’m holding Melinda Harmon’s remarks here because Melinda’s car broke down. Has anyone ever had their car break down on a day that’s important to them?... I think that story’s a little too common. People struggling in a tough moment, wondering ‘How am I going to get my car fixed? How am I going to pay the rent next month? How am I going to keep that We Energies call from coming in? How am I going to keep food on the table?’... The powerful thing about the story of people like Melinda is she just keeps on going,” Rickman said. “And Melinda got involved in fighting to win a union right here, along with 1,000 other people. The working class of the service industry has started to transform what’s going on in this city, because people like Melinda and other folks you’re gonna hear from got together and said, ‘We work together, so we’re gonna fight together’... Melinda helped create an industry-leading union contract at this place right here, to raise the wage not only to $15 immediately, but on a path to increase wages over two-thirds what they were before the union came in… right over there where the Bradley Center used to be.” (Rickman referred to what is now the Fiserv Forum.) Speakers echoed the sentiment of these remarks. Wanda Lavender, who is a mother of six children and has worked at Popeyes for four years, stated that even as a manager at Popeyes, she still only makes $12 an hour. “Like many Black workers who are stuck in low-paying jobs, I kept going to work through this pandemic. I can’t work my job from the safety of my home, and I can’t afford to take off,” she began. “People come in and don’t want to wear face masks so we risk getting exposed to a deadly virus... A few times, I’ve been scared that I have COVID-19. Even though I was feeling sick, coughing my lungs out, my job told me to come in. They said, ‘If you take off time because you are sick, you won’t have a job to come back to.’ No one should be forced to risk their health and safety for a paycheck you can hardly survive on.” Lavender credited “workers in the streets making demands and changing public opinion” for politicians supporting the $15 minimum wage, and referenced Joe Biden as one of them. Julia Derby, a recent graduate of UWM, was going to school full time and working two jobs when the pandemic hit. She graduated during the pandemic and noted that she has no plan for paying back her student loans. “I’m too preoccupied with how I’m going to pay the rent,” she said. Derby slammed President Trump for “granting tax breaks to corporations and billionaires while refusing to raise wages or guarantee income replacement when people can’t work.” She also criticized the GOP’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis, saying they have “massively mishandled and politicized COVID instead of prioritizing the health, safety and wellbeing of frontline and unemployed workers.” She continued, “We see their failures and we see a different future.” Anthony Steward, former cook at the Fiserv Forum, made remarks about the history of the struggle for labor rights in Milwaukee specifically, saying that it was “once known as the best place in America for Black folks to raise a family.” Steward said that was so because of workers uniting “in our workplaces, and at the ballot box to elect policy-makers who would help rewrite the rules and enable us to win unions that balanced the power between workers and bosses.” Bringing it back to the present, he said, “Political action also took it away. As soon as we won, the forces against us—billionaires and the boss class, Wall Street and the 1%—started trying to turn back our progress.” Our world now “looks a lot like the world before workers fought to change it,” he said, going on to emphasize the need for a renewed workers’ movement. Justin Otto, who worked at The Pabst Theatre until March when live music events were all cancelled, referenced his conversations with service workers in Milwaukee: “Every single person I’ve talked to who’s back at work has had to deal with extra concerns, extra precautions, and extra work on top of their normal job, but they’re not getting any extra pay.” He went on to say that hearing these things are “really upsetting… but it’s not surprising.” “It’s exactly what we can expect when decisions are made without us,” Otto said. “It’s exactly what we can expect when elected officials represent our bosses, corporations and themselves, instead of us. It’s exactly what we can expect until we elect different leaders and then demand that they listen to us.” The final speaker was Troy Brewer, a father of three and former employee of the Fiserv Forum, Miller Park, and Jose’s Blue Sombreros. “I worked three jobs, not by choice but out of necessity,” Brewer said. “What I have is hope and optimism that we, the people, meaning all the working people, can get through this thing together. As these jobs are coming back we know we can’t go back to the way things were. Normal doesn’t cut it for us. Normal was over 400 years of oppression and my people are still struggling. Normal was people having to work three jobs out of necessity. We can’t go back to normal. We have to build something new.” Brewer laid out his own vision for the future, where “Black lives matter… the educational system (is) revamped so that minorities in public schools get the same education and opportunities as private and suburban school children get” and “billionaire corporations pay their fair share.” “Now, let’s march over to the MATC and vote together for Biden/Harris, and vote for that brighter future,” Brewer said. Although speakers seldom referenced the Democratic Party as who would get their vote, MASH is openly supportive of the Biden/Harris ticket. Lindsay Adams, Lead Organizer at MASH, said that in terms of workers’ rights, another Trump administration will mean “reacting and protecting,” instead of moving forward. “One example might be the National Labor Relations Board, which is like the court system for unionization and union-related complaints and decisions. They oversee union elections, contract compliance, grievances, etc. Usually it’s a bipartisan body, where you would have republicans and democrats. And there are typically five people who serve on the National Labor Relations Board. Well since Trump has been in office, he’s only put three people in, not five, and all of them have been republican.” “In general, there’s this mismatch that you see as an extreme during the pandemic where on the one hand, we have all these people who are out of work and need work, and on the other hand we have all of these things that need doing, that are not being done. So something like the Green New Deal, where we have good union jobs with high wages and benefits and people trained to do the things like transition to a green economy. A Green New Deal is something that we would be pushing for and we would definitely not be seeing under Trump. There are plenty of Public Works projects that are needed and there are plenty of workers out there who need good quality, family supporting jobs. The thing is that we need a government that can match those two things together,” Adams said. When asked for an official stance from MASH on the election, Adams said, “People are suffering and so is the climate. And so we do have the opportunity with someone who has publicly supported a Green New Deal, a public option in health care, unionization protections for workers, and a $15 minimum wage. These are already public commitments that Joe Biden has made, and so it is our position that we are going to be able to work with administrations that publicly support the things we care about to move the working class agenda forward. Whereas we know already that will be an impossibility with Trump. It’s damage control with him.” MASH represents all of the workers at the Fiserv Forum. Adams said originally when they were going to build the arena, the owners wanted tax subsidies (public money) to do this, but several community groups asked for agreements on what these tax subsidies will generate for the city of Milwaukee, and particularly for working class people and people of color. “Out of that came a Community Benefits Agreement, where in exchange for these tax subsidies, the arena had to hire at least 50 percent of their work force from zip codes with the highest unemployment rates in Milwaukee, with MASH enforcing that requirement. They had to maintain neutrality if there was a union drive, so we had work site access on the ground every day to workers to begin discussions around unionizing and also a path beyond $15 an hour. These were parts of the Community Benefits Agreement. So workers opted to unionize, that’s over 1000 employees at the arena, and bargain their first contract which was finally ratified and set to go into place the week that COVID hit, when the NBA season was cancelled and the arena as well as others across the country were shut down. So our members are now temporarily but long-term unemployed, since March.” Having a union helped with their unemployment situation, according to Adams. “Everything from making sure that members had the appropriate unemployment information so that they could file very quickly, or if there were errors on the side of the employer, making sure that those were corrected so that people could get their unemployment benefits as soon as possible, to when they started having events without fans but still needed staff, making sure that those people who were hired were based on the agreements in the contract based on seniority and that they were paid under what should be their wages in the contract,” Adams said. MASH made a reservation for the group to vote together at MATC ahead of time. Photo Credits to MASH About the Author:

My name is Maddy. I am a journalist, writer, and thinker based in Colorado where I work as a stringer for a small-town newspaper and have some odd jobs on the side. I am a member of the Democratic Socialist of America and am interested in bringing a lens of intersectionality to journalism and "pushing the envelope" to make people think critically about social issues. I love animals, music, food, creative writing, and the outdoors. She/her. Therefore political power must, for the working classes, come straight out of the Industrial The interest that so many have expressed in forming a workers/labor party shows that many are disgusted by our current political system. This disgust is shared by many throughout our state (Iowa) and country but has manifested itself in different directions, not entirely in our favor. There is no doubt in my mind that a workers/labor party is essential to securing political victories for the working class; however, I think that a clear and sober look at the current class dynamics within our state and country is necessary to establish our next steps.

The struggle between capital and labor waged throughout the twentieth century had battlefields all throughout the United States. Due to industrial pressure inflicted by the working class, many workers were able to secure a decent standard of living across the country from the 1940s until the 1970s-1980s. But the position of workers, their communities, their politics, and their unions was hollowed out by the neoliberal politics that was to arise out of the Reagan administration and remained unchecked by the Democratic opposition. In fact, it was largely adapted by the Democratic Party itself. From the 1980s until today, the Democratic Party has seen its support amongst workers eroding. At one point, the Party was a vehicle for workers to gain political concessions, but since the 80s, and even more specifically in 2016, workers left the Party in favor of the politics of Trump. The collective workers struggle was struck down by Reagan and it is a shame that workers turned around and voted for Trump, who on the one hand, gave lip service to American workers and on the other hand has implemented many Reagan-esque policies. A sign of how far the struggle has fallen. In 2016 and in 2020 the opposition to neoliberalism has been entirely based around the politics of Bernie Sanders. He seemed to articulate an alternative to politics as usual and his appeal in 2016 reached into areas that the Democrats had been failing to reach. As impressive as Bernie’s two campaigns were, the movement for socialism in the United States was never going to be successful upon the back of an individual alone. There are a lot of things that we need to learn from Bernie and the movement that surrounded him. And it is our imperative to learn from the successes and failures in order to continue the struggle for socialism in the United States. As socialists, we believe that there are twin pillars of power within society, the industrial and the political. Bernie’s campaign showed how disconnected the two struggles were and yet, Bernie was unable to marry the two completely. Bernie was able to bring many young and apolitical people into his movement but his movement remained largely a political one. Historically, socialists moved from the industrial battlefield to the political battlefield, whereas Bernie’s movement attempted to do the opposite. It is our imperative then, if we wish to continue any sort of left movement within the United States, to focus on the industrial wing of our movement; a wing that has been neglected by the left over the past decades. The industrial wing is our base and our electoral success or failure will be a reflection of our progress on the industrial battlefield. As the conquest of the political state is the echo of the industrial struggle, the industrial struggle is best represented by the state of our labor movement. After four decades of neoliberal assault upon the labor movement, the movement itself remains extremely weak. Our unions have been placed on their back foot and have had to accept trade deals and legislation that have hindered their ability to organize. The deindustrialization that has ruined many communities throughout the country played no small part. But even with that concerted effort on behalf of capital, we see in the midst of the crisis today, that it is labor, not capital, that keeps the world running. It then becomes the imperative of socialists to focus on the point of production, the workplace, in order to build the base for future electoral movements. It was James Connolly who stated, “the socialism which is not an outgrowth and expression of that economic struggle is not worth a moment’s serious consideration.” If we should take anything from Bernie, it should be his insistence upon rebuilding a fractured labor movement in the United States. We mustn’t put the cart before the horse. As Eugene Debs noted, “We can have no effective Labor Party without the backing and support of the labor unions.” That isn’t to say that the political struggle is currently irrelevant, but rather that we need to rebuild the base of our political struggle. To paraphrase Connolly, when labor finds itself in the position to control industry by economic pressure, it finds that the state must bend to our will – or break. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed