|

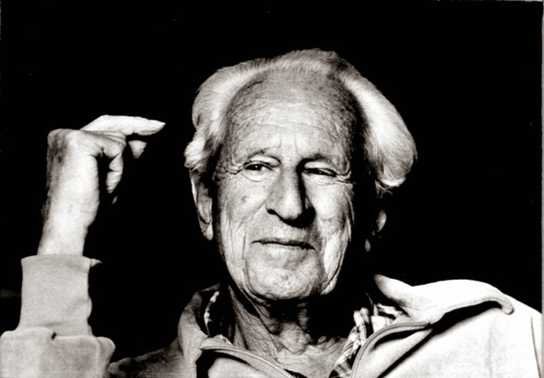

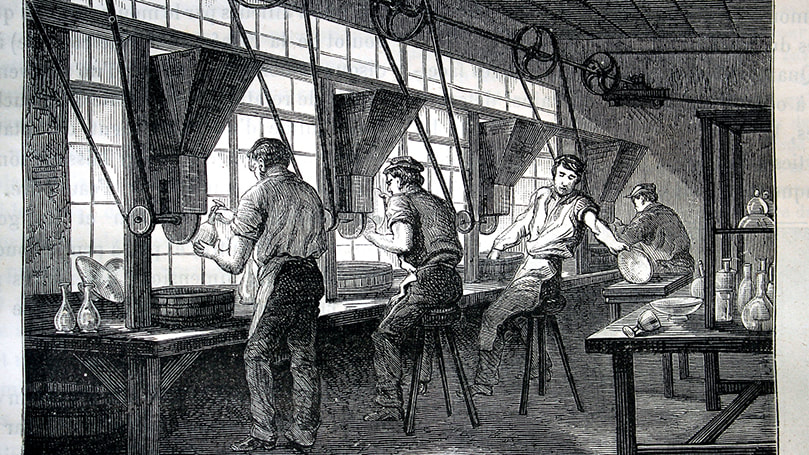

5/31/2021 The Relevance of Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man and its Failures. By: Carlos L. GarridoRead NowPosing the Question This year marks the 57th anniversary of Herbert Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man (1964). This text, although plagued with a pessimistic spirit, was a great source of inspiration for the development of the New Left and the May 68 uprisings. The question we must ask ourselves is whether a text that predates the last 50 years of neoliberalism has any pertinent take-aways for today’s revolutionary struggles. Before we examine this, let us first review the context and central observations in Marcuse’s famed work. Review Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man[i] (ODM) describes a world in which human rationality is uncritically used to perpetuate the irrational conditions whereby human instrumental ingenuity stifles human freedom and development. In the height of the cold war and potential atomic devastation, Marcuse observes that humanity submitted to the “peaceful production of the means of destruction” (HM, ix). Society developed its productive forces and technology to a scale never before seen. In doing so, it has created the conditions for the possibility of emancipating humanity from all forms of necessity and meaningless toil. The problem is, this development has not served humanity, it has been humanity that has been forced to serve this development. The instruments humans once made to serve them, are now the masters of their creators. The means have kidnapped the ends in a forced swap, the man now serves the hammer, not the other way around. The observation that our society has developed its productive forces and technologies in a manner that creates the conditions for more human freedom, while simultaneously using the development itself to serve the conditions for our un-freedom, is not a new one. The Marxist tradition has long emphasized this paradox in the development of capitalism. Marcuse’s ODM’s novel contribution is in the elucidation of the depth of this paradox’s submersion, as well as how this paradox has extended beyond capitalism into industrialized socialist societies as well. Let us now examine how Marcuse unfolds the effects of modern capitalist instrumental rationality’s closing of the political universe. Whereas the capitalism Marx would deal with in the mid-19th century demonstrated that along with clearly antagonistic relations to production, the working and owning class also shared vastly different cultures, modern one-dimensional society homogenizes the cultural differences between classes. Marcuse observes that one of the novelties of one-dimensional society is in its capacity to ‘flatten out’ the “antagonisms between culture and social reality through the obliteration of the oppositional, alien, and transcendent elements in higher culture” (HM, 57). This process liquidates two-dimensional culture and creates the conditions for social cohesion through the commodification, repressive desublimation, and wholesale incorporation and reproduction of these cultural elements into society by mass communication. In essence, the cultural differences the working and owning class had have dissipated, both are integrated in the same cultural logic. This does not mean there is no cultural opposition, but that the cultural opposition is itself “reduced” and “absorbed” into the society. Today, this absorption of the opposition is more visible than ever. Companies that donate millions to police departments post #BLM on their social medias, repressive state apparatuses who assaulted homosexuals in the 60s lavender scares now wave the LGBTQ+ flag, billion-dollar companies like Netflix who take loopholes to not pay taxes make a show on ‘democratic socialist’ Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, etc. All throughout our one-dimensional culture we experience the absorption of an ‘opposition’ whom in being absorbed fails to substantially oppose. This could be reformulated as, ‘all throughout our one-dimensional culture we experience the absorptions of any attempts at a great refusal, whom in being absorbed fail to substantially refuse.’ How did this happen? Well, in a way that paradoxically provides the material confirmation of Marxism as a science (according at least to Popper’s falsifiability requirement), while disconfirming one of its central theses, modern capitalism seems to have mended one of its central grave digging contradictions, the antagonistic contradiction between the proletariat and the owning class. According to Marcuse, modern industrial society has been able to do this because it provided the working masses (and society in general) a “comfortable, smooth, reasonable, democratic unfreedom” (HM, 1). It superimposed on the working masses false needs which “perpetuate [their] toil, aggressiveness, misery,” and alienation for the sake of continuing the never-ending hamster wheel of consumption (HM, 5). In modern industrial society people are sold a false liberty which actively sustains them in a condition of enslavement. As Marcuse states, Free choice among a wide variety of goods and services does not signify freedom if these goods and services sustain social controls over a life of toil and fear – that is, if they sustain alienation (HM, 8). In essence, that which has unnecessarily sustained their working life long, exploitative, and alienating, has made their life at home more ‘comfortable.’ This consumerist, Brave New World-like hellish heaven has perpetuated the prevalent ‘happy consciousness’ present in modern industrial society, where your distraction, comfort, and self-identification with your newly bought gadgets has removed the rebellious tendencies that arise, in a Jeffersonian-like manner, when the accumulation of your degradation reaches a certain limit where revolution becomes your panacea. The phenomenon of happy consciousness, says Marcuse, even forces us to question the status of a worker’s alienation, for although at work alienation might continue, he reappropriates a relation to the products through his excessive identification with it when purchased as a consumer. In this manner, the ‘reappropriation’ of the worker’s alienation to the product manifests itself like Feuerbach’s man reappropriating his species-being now that it has passed through the medium (alienated objectification) of God – the commodity here serving the mediational role of God. The working mass, as we previously mentioned, is not the only one affected by the effects of one-dimensional society. Marcuse shows that the theorists are themselves participatory and promotional agents of this epoch. Whether in sociology or in philosophy, the general theoretical trends in academia are the same; the dominance of positivist thinking, and the repression and exclusion of negative (or dialectical) thinking. This hegemonized positivist thought presents itself as objective and neutral, caring only for the investigation of facts and the ridding of ‘wrongful thought’ that deals with transcendental “obscurities, illusions, and oddities” (HM, 170). What these one-dimensional theorists do is look at ‘facts’ how they stand dismembered from any of the factors that allowed the fact to be. In doing so, while they present their task as ‘positive’ and against abstractions, they are forced to abstract and reify the fact to engage with it separated from its context. By doing this these theorists limit themselves to engaging with this false concreteness they have conjured up from their abstracting of the ‘fact’ away from its general spatial-temporal context. Doing this not only proves to be futile in understanding phenomena – for it would be like trying to judge a fight after only having seen the last round – but reinforces the status quo of descriptive thinking at the expense of critical and hypothetical thought. As Marcuse states, This radical acceptance of the empirical violates the empirical, for in it speaks the mutilated, “abstract” individual who experiences (and expresses) only that which is given to him, who has only the facts and not the factors, whose behavior is one-dimensional and manipulated. By virtue of the factual repression, the experienced world is the result of a restricted experience, and the positivist cleaning of the mind brings the mind in line with restricted experience (HM, 182). Given that “operationalism,” this positivist one-dimensional thought, which in “theory and practice, becomes the theory and practice of containment,” has penetrated the thought and language of all aspects of society, is there an escape to this seemingly closed universe (HM, 17)? As a modest dialectician, Marcuse denies while leaving a slight ‘chance’ for an affirmation. On one end, the text is haunted by a spirit of pessimistic entrapment – not only has the logic of instrumental rationality that sustains one-dimensional society infiltrated all levels of society and human interaction, but the resources are vast enough to quickly absorb or militarily “take care of emergency situations”, viz., when a threat to one-dimensional society arises. On the other end, he says that “it is nothing but a chance,” but a chance nonetheless, that the conditions for a great refusal might arise (HM, 257). Although he argues dialectical thinking is important to challenge capitalist positivism, he recognizes dialectical thinking alone “cannot offer the remedy,” it knows on empirical and conceptual grounds “its own hopelessness,” i.e., it knows “contradictions do not explode by themselves,” that human agency through an “essentially new historical subject” is the only way out (HM, 253, 252). The contingency of this ‘chance’ is dependent on the contingency of the great encounter between the “most advanced consciousness of humanity” and the “most exploited force,” i.e., it is the ‘barbarians’ of the third world to whom this position of possible historical subjectivity is ascribed to (HM, 257). Nonetheless, Marcuse is doing a theoretical diagnosis, not giving us a prescriptive normative approach. The slight moment where a glimpse of prescriptive normativity is invoked, he encourages the continual struggle for the great refusal. This is how I read the final reference to Walter Benjamin, “[critical theory] wants to remain loyal to those who, without hope, have given and give their life to the Great Refusal” (Ibid.). Even if we are hopeless, we must give our life to the great refusal. We must be committed, in Huey Newton’s terms, to “revolutionary suicide”, to foolishly struggling even when no glimpse of hope is to be found, for only in struggling when there is no hope, can the conditions for the possibility of hope arise. AnalysisThere are very few observations in this text to which we can point to as relevant in our context. The central thesis of a comfortable ‘happy consciousness’ which commensurates all classes under a common consumerist culture is a hard sell in a world in which labor has seen its century long fought for gains drawn back over the last 50 years.[ii] Neoliberalism has effectively normalized what William L. Robinson calls the “Wal-Martization of labor,”[iii] i.e., conditions in which work is less unionized, less secure, lower paid, and given less benefits. These conditions, along with the growing polarization of wealth and income, render Marcuse’s analysis of the post-WW2 welfare state impertinent. I lament to say that the most valuable take-away of ODM for revolutionaries today is where it failed, for this failure continues to be quite prevalent amongst many self-proclaimed socialist in the west. This failure, I argue, consist of Marcuse’s equating of capitalist states with socialist experiments. Marcuse’s ODM unites the socialist and capitalist parts of the world as two interdependent systems existing within the one-dimensional logic that prioritizes “the means over the end” (HM, 53). For Marcuse, the socialist part of the world has been unable to administer in praxis what it claims to be in theory; there is effectively a “contradiction between theory and facts” (HM, 189). Although this contradiction does not, according to him, “falsify the former,” it nonetheless creates the conditions for a socialism that is not qualitatively different to capitalism (Ibid.). The socialist camp, like capitalism, “exploits the productivity of labor and capital without structural resistance, while considerably reducing working hours and augmenting the comforts of life” (HM, 43). In essence, his argument boils down to 20th century socialism being unable to create a qualitatively new alternative to capitalism, and in this failure, it has replicated, sometimes in forms unique to it, the mechanisms of exploitation and opposition-absorption (through happy consciousness, false needs, military resistance, etc.), that are prevalent in the capitalist system. There are a few fundamental problems in Marcuse’s equalization, which all stem, I will argue, from his inability to carry dialectical thinking onto his analysis of the socialist camp. In not doing so, Marcuse himself reproduces the positivistic forms of thought which dismember “facts” from the factors which brought them about. Because of this, even if the ‘facts’ in both camps appear the same, claiming that they are so ignores the contextual and historical relations that led to those ‘facts’ appearing similar. For Marcuse to say that the socialist camp, like the capitalist, was able to recreate the distractingly comfortable forms of life that make for a smoother exploitation of workers, he must ignore the conditions, both present and historical, that allowed this fact to arise. Capitalism was able to achieve this ‘comfortable’ life for its working masses because it spent the last three centuries colonizing the world to ensure that the resources of foreign lands would be disposable to western capital. This process of western capitalist enrichment required the genocide of the native (for its lands), and the enslavement of the African (for its labor) and created the conditions for the 20th century struggle between western capital for dividing up the conquered lands and bodies of the third world. But even with this historical and contextual process of expropriation and exploitation, the fruits of this were not going to the working classes of the western nations because of the generosity of the owning class, regardless of how much they benefited from creating this ‘labor aristocracy.’ Rather, the only reason why this process slightly came to benefit the popular classes in the US was a result of century long labor struggles in the country, most frequently led by communists, socialists, and anarchist within labor unions. The socialist camp, on the other hand, industrialized their backwards countries in a fraction of the time it took the west, without having to colonize lands, genocide natives, or enslave blacks. On the contrary, regardless of the mistakes that were made, and the unfortunate effects of these, the industrialization process in the socialist camp was inextricably linked to the empowering of the peripheral subjects, whether African, Asian, Middle-Eastern, or Indo-American, that had been under the boot of western colonialism and imperialism for centuries. The ‘third-world’ Marcuse leaves the potential role of historical subjectivity to, was only able to sustain autonomy because of the solidarity and aid – political, military, or economic in kind, it received from the socialist camp. Those who were unable, for various reasons, to establish relations with the socialist camp, replicated, in a neo-colonial fashion, the relations they had with their ‘previous’ metropoles. In fact, history showed that the ‘fall’ of this camp led the countries in the third world that sustained an autonomous position (thanks to the comradely relations they established with the socialist world), to be quickly overturned into subjected servitude to western capital. By stating that the socialist camp was unable to affect a materialization in praxis of its theory, and as such, that it was not qualitatively different from capitalism (making the equating of the two possible), Marcuse effectively demonstrates his ignorance, willful or not, of the geopolitical situation of the time. Socialism in the 20th century could not create its ideal qualitatively new society while simultaneously defending its revolution from military, economic, and biowarfare attacks coming from the largest imperial powers in the history of humanity. Liberation cannot fully express itself under these conditions, for, the liberation of one is connected to the liberation of all. The communist ideal whereby human relations are based “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need,” is only realizable under the global totalizing disappearance of all forms of exploitation and oppression. It is idealist and infantile to expect this reality to arise in a world where capitalism exists even at the farthest corner of the earth, even less in a world where the hegemonized form of global relations is capitalistic. Nonetheless, even Marcuse is forced to admit that the socialist camp was able to create a comfortable life for its working masses. But, unlike Marcuse argues, this comfort in the socialist camp cannot be equated with comfort in the capitalist camp. Not only are the conditions that led to the comfort in each fundamentally different (as just previously examined), but the comfort itself, as a fact, was also radically different. In terms of job security, housing, healthcare, education, childcare, and other forms of government provided social securities, the comfort in the socialist camp was significantly higher than the comfort experienced by the working masses in the welfare social democracies in Europe, and tenfold that of the comfort experienced by the working masses in the US. When to this you add the ability for political participation through worker councils and the party, the prevalent spirit of solidarity that reigned, and the general absence of racism and crime, the foolishness of the equalization is further highlighted. Nonetheless, the comparison must not be made just between the capitalist and socialist camp, but between the conditions before and after the socialist camp achieved socialism. Doing so allows one to historically contextualize the achievements of the socialist camp in terms of creating dignified and freer lives for hundreds of millions of people. For these people, Marcuse’s comments are somewhere between laughable and symbolic of the usual disrespect of western intelligentsia. Although Marcuse was unable to live long enough to see this, the fall of the socialist camp, and the subsequent ‘shock therapy’ that went with it, not only devastated the countries of the previous socialist camp – drastically rising the rates of poverty, crime, prostitution, inequality, while lowering the standard of living, life expectancy, and the opportunities for political participation – but also the countries of the third world and those of the capitalist camp themselves! With the threat of communism gone, the third world was up for grabs again, and the first world, no longer under the pressure of the alternative that a comfortable working mass in the socialist camp presented, was free to extend the wrath of capital back into its own national popular classes, eroding century long victories in the labor movement and creating the conditions for precarious, unregulated, and more exploitative work. Works like One-Dimensional Man, which take upon the task of criticizing and equating ‘both sides,’ do the work of one side, i.e., of capitalism, in creating a ‘left’ campaign of de-legitimizing socialist experiments. This process of creating a ‘left’ de-legitimation campaign is central for the legitimation of capital. This text (ODM) is the quintessential example of one of the ways capitalism absorbs its opposition by placing it as a midpoint between it and the real threat of a truly socialist alternative. It is because the idealistic and non-dialectical logic of capital infiltrates these ‘left’ anti-communist theorists that they can condemn and equate socialist experiments with capitalism. If there is a central takeaway from Marcuse’s text, it is to guard ourselves against participating in this left-anticommunism theorizing that prostitutes itself for capital to create the conditions whereby the accidental ‘faults’ of pressured socialist experiments are equated with the systematic contradictions in capitalist countries. In a world racing towards a new cold war, it is the task of socialists in the heart of the empire to fiercely reject and deconstruct the state-department narratives of socialist and non-socialist experiments attempting to establish themselves autonomously outside of the dominion of US imperialism. Acknowledging how Marcuse failed to do this in ODM helps us prevent his mistake. Notes [i] Reference will be to the following edition: Marcuse, Herbert. One-Dimensional Man. (Beacon Press, 1966). [ii] Perhaps even longer, for The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 had already began these drawbacks. Nonetheless, 1964 is a bit too early to begin to see its effects, especially for an academic observing from outside the labor movement. [iii] Robinson, L. William. Latin America and Global Capitalism. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008)., p. 23. AuthorCarlos L. Garrido is a philosophy graduate student and assistant at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. His specialization is in Marxist philosophy and the history of American socialist thought (esp. early 19th century). He is an editorial board member and co-founder of Midwestern Marx and the Journal of American Socialist Studies. Archives May 2021

1 Comment