“A radical is no more than this: he who goes to the roots. Let him who fails to arrive at the bottom of things call himself not a radical; nor let him who fails to help other men obtain security and happiness call himself a man.”- Jose Marti [1] The word radical is one that is thrown out very loosely by both ruling class parties in the US. When the democratic primary was taking place, self-proclaimed democratic socialist Bernie Sanders was hailed as too radical by the democratic establishment. Now that the race is between Trump and Biden, the republicans are pushing the narrative that Biden and those involved in his campaign are radical leftists. In this work we will examine what it means to be a radical and what relation does radicalism have to extremism and socialism. Instead of going straight into what radicalism is, let us examine it through what it is not. The reasons for talking about what it is not should be obvious given the previous example of its usage in categorizing two dramatically different candidates as radical. In the US, radicalism becomes pejoratively synonymous with extremism and socialism; this is part of the general trend of linguistic kidnapping of concepts to be manipulated for the interest of our ruling class (one can throw democracy, freedom, etc. in here too). Racialism and Extremism In the US you will hear the interchangeability of radical Islam and Islamic extremism. As if radicalism and extremism meant the same thing. The reality is that both in practice and by definition this is false. In practice, the radicals in countries that are primarily Muslims are not the ones terrorizing innocent people or planning horrendous attacks. Rather the radicals are the ones that get at the root of the problem in the middle east. They are the ones who realize that America’s destabilization of the area, for economic and political ends, has been what has caused the rise in Islamic fundamentalism. And if they are militant radicals, their goal is to not only fight off imperialism, but also fight off the monster it created in Islamic extremism. Here we see that the radical is the one that would fight not only against the root of the problem, but also the extremism that root created. Thus, any synonymous usage of radicalism and extremism in practice holds to false given the tensions and struggle of one against the other. If we analyze what extremism and radicalism mean by definition, we also notice that one has nothing to do with the other. Extremism implies the positioning of oneself at a pole. This means going to the extreme ends of the given totality, while not inherently threatening to substantially change it. For example, Islamic extremism, regardless of how out of the current totality it presents itself as, still functions within the existing structures of global capitalism. The social atmosphere might be different, but we can see in countries like Saudi Arabia that capitalism is not threatened by their Islamic ideology. On the contrary, it seems to be that this Islamic extremism fits nicely within the global system as the evil boogie man the US uses to fight imperialist wars. This does not mean that fighting terrorism is wrong, on the contrary; rather that the terrorism of Islamic extremism is a profitable ideological tool for the US to expand its material and ideological hegemonic power. We can also look at white nationalist extremism, both historically and in the present. The Nazi’s held extremist and barbaric positions. But they did not present an essential threat to the existing order; rather they were themselves capitalist. The rising trends of white nationalism and far right extremism in the US is another perfect example of this. This trend is one which does not seek to overthrow the essential conditions holding society together, but to go to the extremes of what is possible within that society. This extreme is in our case a reactionary return to a more militant racism rather than the more obscure and gray area one we generally find today. The general trend we find in extremism, whether in the example of Islam or white nationalism, is the inability to be fully radical. This means that they always fall short in their analysis of the problem, and thus, their inability to see the real source of the problem provides the framework for the wrong solution. The Islamic extremist falls short in seeing that their condition is not a result of Americans per say, but of America’s foreign policy; the same one that uses and manipulates Americans to go fight wars in which they either die or return drastically damaged physically, mentally, or both for the sake of the enrichment of the already ridiculously wealthy. The white extremists fall short in realizing that the polarization of wealth and loss of jobs over the last 50 years in the US is not a result of immigrants, blacks, or people of color; rather it is the result of capitalism, specifically in its neoliberal form, which has shipped manufacturing jobs overseas to profit of cheap labor while systematically dismantling the power workers had through their unions and collective bargaining efforts. In both cases what we find is the inability to see the real source of the problem. This is a mistake which leads to the barbarity of the positions taken. These are essentially positions which end up attacking fellow exploited people while letting the common exploiter off the hook. It is a position of weakness because it deviates the blame from the powerful to the powerless. It prefers the easier and mystical opponent, rather than the real and potent one. Radicalism, on the contrary, is measured by its ability to see the real source of the problem. This means that radicalism is not a fixed position. It is not a position in which the same stance is deemed radical in all places at all times. For example, the bourgeois writers of the 17th and 18th century were pretty radical for their time. The John Locke-s and Rousseau-s, although representing different currents of liberalism, both were radicals because they were able to get at the root of their times, and propose alternatives based on a substantial differentiation of their epoch. Locke introduces the right to revolution which is central to the American experiment, and Rousseau the rights of humanity which are central to the French revolution of 1789. Today, both of their positions are either mainstream of have already been surpassed. No one would claim that Locke’s views on property hold their radicalness today. Although one might say that Rousseau’s writings or Locke’s right to revolution still might be radical. The point is that radicalism is based on historical context; sometimes the roots of that historical context remain essentially the same, and thus the radical approach of 300 years ago remains radical. But with the changing of the roots comes the loss of the radicalness of the previous radicalism. Although, given that new roots are not born in a vacuum, but are a result of a specific historical context, it could very well be that an attack to the old roots might still partially reach the new roots, given the new roots retain elements of the past roots. Biden the Radical Before we talk about radicalism and socialism, I think it would be fair to address a point made at the beginning of the work. This point is the Trump campaign’s labeling of Joe Biden as a radical leftist. I don’t think much really needs to be said here, given that anyone who could see two fingers in front of them realizes the stupidity of these allegations. But for the sake of not leaving any arguments unanswered, I feel obliged to comment at least a sentence or two on this. To label Joe Biden as a radical is an insult to stupidity itself. Joe Biden represents the reactionary move towards a pre-Trump America. This move is perhaps the antithesis of radicalism, as not only does it not strive to destroy the roots of the problem which led to the Trump symptom, but it seeks actively to empower those roots even more. In essence, it does not seek to change the conditions which allowed an imbecile like Trump to arise, but rather to retain them without their Trump-effect. It wants to eliminate the cold sweats by returning to the fever. Without realizing that not only does the cold sweat represent essentially a continuation of the fever, but the fever itself is what led to the cold sweats. Radicalism and SocialismHaving now dismissed these allegations of Biden as a radical, let us question the relation of socialism and radicalism. As we already previously mentioned, radicalism consist of being able to not only reach the root of the problem, but actively try to change the situation through an attack directly aimed at the roots. Radicalism is not in any sense a passive exercise. This means that radicalism cannot just seek to interpret the roots of the problem. Radicalism implies praxis. It implies an active struggle to change the conditions of what is, through the awareness and attack of the roots of what is. Radicalism is at the heart of the philosophy of praxis; the type of philosophy that Marx described as not only interpreting the world but actively trying to change it.[2] Thus, what is the relationship of radicalism to socialism? On the topic of radicalism, Marx states that: “To be radical is to grasp things by the root. But for man the root is man himself”[3] The first part we have already established. This root essentially means getting at the foundational essence of the object of examination. It means getting at that which serves as the first cause of all things experienced in a totality. For Marxist, this is the level of how things are made. It is the level of production. Thus, the root is always the economic structure of the time. The second part of the quote serves to affirm that this root is always based on relations between human beings. The root is not in the divine, it is in the way human beings interact with each other in the process of making their means of subsistence. Thus, we see here that radicalism is necessarily based on spatial-temporal contexts. What was considered radical in 14th century Germany is not considered radical in today’s Germany. What is considered radical right now in the US is not considered radical in China. For example, the policies Bernie’s platform was calling for, although not radical anywhere else in the developed world, in a country where even the basic necessities of life are privatized, calling for the removal of the profit motive in education or healthcare is radical. It gets, at least partially, at the root of the extent to which privatization has reached in the US. But the same proposals that Bernie made would not at all have been radical in the UK, where they have a national health system. On the contrary, over there, single payer health care represents a step back. Bernie’s policy to make public colleges and universities tuition free is radical in the US, given the debt higher education forces everyone in; but this policy in Germany would not be radical given they already have higher education basically for free. Thus, does radicalism mean socialism? The answer is clearly no. A radical in one moment might not be a radical in another, even if he does not change any of his views. For example, in the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte Marx lays out how the first coalition was made by the different classes in France to overthrew the aristocracy and establish the republic; but how in 1848, when the proletariat rises to expand the republic to a democratic (socialist) one, the allies who helped overthrow the aristocracy join to suppress the proletarian uprising.[4] What we see here is the contextual basis of radicalism. When one is in what is essentially a monarchy, the struggle for a bourgeois republic is a radical fight. It seeks to transform the roots of society. But the section of radicals who now have the power in the bourgeois republic no longer stand as radical. Now (1848) they are the conservatory force fighting to maintain the existing order from the threat of a proletarian revolution. This forces us to make two important distinctions in the type of subjects that embody radicalism. The first is the contextual radical. The contextual radical is the person or group that is radical only in their epoch. This is the example of the bourgeoisie. The bourgeois class, in its struggle against the feudal order represented a radical subject. Once the new order established was the one their class benefited from, they no longer stand as a radical force, but rather as a conservatory one. One which seeks not to transcend the roots of the existing structure, but to preserve them. The other form of radicalism I call consistent radicalism. Consistent radicalism is the subject which is constantly attacking the roots of the existing order for the sake of the progression of history. It is the subject which fought with the bourgeois against the aristocracy but did not conservatize when the bourgeois class achieved power. Rather, now they fought with the new revolutionary proletariat in order to radically transform the existing order of capitalism. Thus, as has been already implied, in our epoch to be radical amounts to being a socialist. The contextual radical is the one whose end is the transcendence of capitalism and the establishment of socialism. In this context, the socialist is the contextual radical, in the same way the bourgeois was the contextual radical in the feudal order. The communist on the other hand, stands as the consistent radical. The one’s whose end is not merely in socialism, but who seeks to actively be the agent which stands in the side of the progression of history. Marx speaks of communism in various different ways. The main way is as the society in which the class structure is eliminated, the state has withered away, and the relations of society are guided by the principle of “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”.[5] But Marx also speaks of communism in terms of the communist subject. In The German Ideology Marx states that: “Communism is not for us a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality will have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.”[6] Thus, communism, the communist subject, here stands as the consistent radical. He who is not concerned with the state of affairs as an end in itself, but who moves towards the progressive abolishment of every existing totality. The communist is the person who in every societal structure that experiences injustice fights for the elimination and transcendence of that injustice; and does so through accessing the roots of that injustice. This does not mean that the communist is the one calling for the overthrow of existing socialist states, but rather the one which gets at the roots of the present problems and fights against them. This means a fight against the pressure of imperialism on socialist states and against the own tendencies of corruption that the hardships of defending a revolution from imperialism might encourage within socialist countries. ConclusionIn conclusion, we have been able to define and distinguish radicalism from extremism and socialism. In doing so we were able to distinguish between two forms of radicalism, contextual radicalism, and consistent radicalism. Finally, thanks to this differentiation of radicalism, we were able to establish the relationship between radicalism, socialism, and communism. Our conclusions where that in our epoch, both forms of radicalism must be socialist. In order to understand and attack the roots of the problem, one must necessarily fight capitalism. But we uncovered that the socialist is the one that remains tied to contextual radicalism. His end is merely the destruction of the present root. Although the communist also strives for the transcendence of capitalism (the present root), his end is not there. The communist stands as a consistent radical; someone who in all moments fights to improve the structures humanity has provided for itself through an approach that focuses on the root of the problem, on the first causes, not on the effects. Citations. [1] Liss, Sheldon. Roots of Revolution: Radical Thought in Cuba. (Nebraska Press, 1987), p. xiii. [2] “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” Marx, Karl. “Thesis on Feuerbach” The Marx & Engels Reader. (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978/1845), p.143. [3] Marx, Karl. “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction” The Marx & Engels Reader. (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978/1844), p. 60. [4] Marx, Karl. “The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” The Communist Manifesto and Other Writings (Barnes & Nobles Classics, 2005/1852), p. 70) [5] Marx, Karl. “Critique of the Gotha Program” The Marx & Engels Reader (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978/1875), p. 531. [6] Marx, Karl. The German Ideology (International Publishers, 1993/1932), p. 56-57.

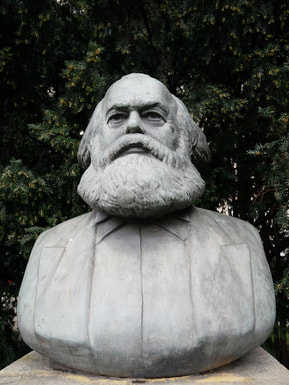

1 Comment

Max

1/9/2022 08:22:44 pm

I enjoyed this

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed