|

7/17/2024 EDITORIAL: Sean O’Brien RNC Speech Shows Why an Anti-Monopoly Party Led by a Class-Oriented Labor Movement is Necessary By: S.M. CIFONE ATU MEMBERRead NowInternational Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) President, Sean O’Brien, to mixed reactions spoke to the Republican National Convention (RNC) Monday night. In a much-criticized speech, O’Brien gave a speech aimed more at the Conservative worker watching at home (and some who may be delegates in attendance) and not the ruling class elites in the room. O’Brien gave a carefully worded speech that show what many class-oriented trade unionists have been saying for a long time, the political system has thrown the American working class under the bus a long time ago. What should grab the attention of workers watching at home is the crowd’s reaction as O’Brien spoke, when speaking in vague, general terms of support for workers it was mostly applause, but when anything that could substantively benefit workers was mentioned the crowd went quiet. The IBT General President speaking at the RNC is a positive step in reaching Conservative workers who have largely been abandoned by business unionist misleadership. Despite saying things that aren’t usually allowed in mainstream political debate, like telling the American workers the corporate elite only have allegiance to profit, more is needed to bring political power back to the labor movement. “American workers own this nation” is a quote that received a mixed reaction in person, but should’ve struck a chord with the workers watching at home. There is truth behind this quote, but is simply playing two capitalist parties against each other enough for workers to exercise this ownership? No, it’s not, but Sean O’Brien breaking the Democratic stranglehold on union leadership provides an opening for class-oriented trade unionists to start a campaign to form a political party for the working class. We as class-oriented trade unionists must lead the way in shifting workers from a “left-vs.-right” political debate to a “Them vs. Us” class-based politics. The way forward is to build an anti-monopoly working-class party that unites all true progressive forces behind a vibrant and militant class-oriented labor movement. Like O’Brien said, “Most legislation is never meant to go anywhere, and it’s all talk”, the only way to change that is for the labor movement to lead the way out of the capitalist-controlled duopoly. AuthorThis article was produced by Labor Today. Archives July 2024

0 Comments

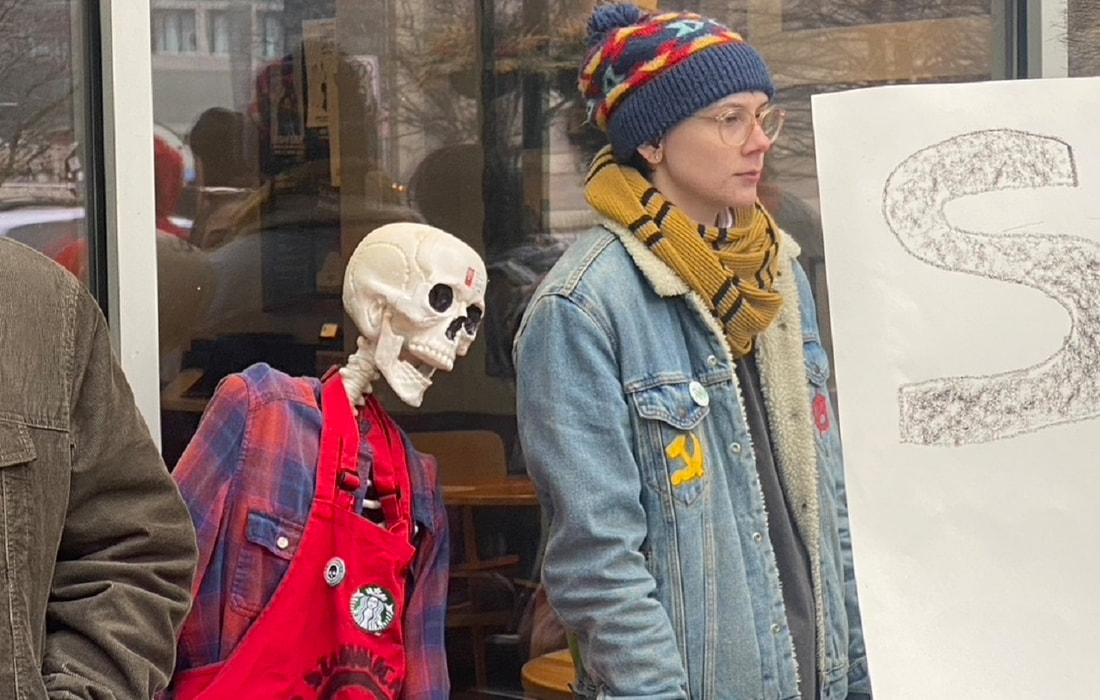

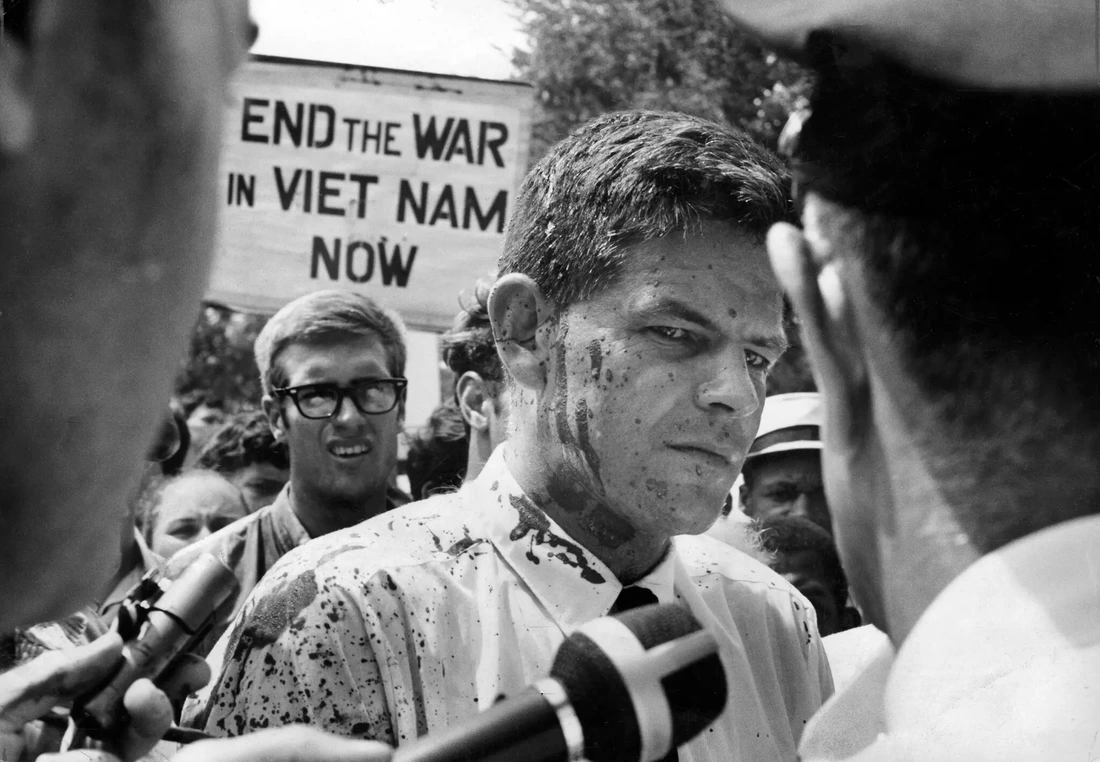

EDITORS NOTE: Just before this posting of Marxism-Leninism Today, it was reported on July 16th that Teamster President Sean O’Brien had requested that President Joe Biden not involve himself in a possible strike at UPS. Final union contract negotiations are proceeding between the Teamsters Union and the gigantic and super-profitable UPS (United Parcel Service) Corporation. Will the 330,000 union members be forced to strike on August 1? Will UPS agree to the reasonable demands of its workforce, preventing any work stoppage? Or, will UPS successfully use President Joe Biden to stall or even break the strike and save the company? Will Biden jump in even if the company doesn’t ask him to? With the recent spectacle of Biden’s contemptible wrecking of the rail union strike just 9 months ago fresh in mind, it’s a real possibility that the self-proclaimed “most pro-union President” may yet again prove that he’s not. WHAT ARE THE ISSUES? The more than 330,000 Teamster members who work for UPS generate enormous profits for the company. This landmark battle has been shaping up for almost 30 years, and has been intensifying to an unprecedented degree this year. UPS personifies the super-profitable U.S. corporation, having generated more than $22 billion dollars in profits in just the past two years alone. UPS controls more than 43% of the U.S. package delivery market and during the pandemic the company saw a huge jump in package volumes as millions of people shopped on-line and required home delivery. UPS has systematically and scientifically designed the delivery process from beginning to end to squeeze maximum efficiency from its workforce, making UPS a very difficult place to work on account of the punishing production requirements and omnipresent management surveillance of everyone at work. Every job is continuously studied, timed, and monitored; whether it be loading the package vans or the time spent delivering them out on a route. Employees who fail to meet the onerous requirements are disciplined and fired. For more information see this detailed explanation of the UPS issues by Teamsters Local 90 President and Business Agent Tanner Fischer https://youtu.be/BL95hDDoc2U from FightBack! Radio. Almost half of the workforce are also hired as part-timers, at far lower starting wages. Combined with the backbreaking production requirements and wages as low as $16 hour, turnover is astronomical. Many of these lower-tier, lower-paid jobs were created during the Hoffa years with his full consent, and the creeping cancer of contracting-out of UPS jobs to unorganized low-wage companies likewise took root on the Hoffa watch. Today’s battle features a major union priority of eliminating the lower-tier wage schemes and limiting and rolling back the contracting-out and loss of union positions. THE COMPANY FEARS ANGRY UNION MEMBERS Initial company bending on the issues of two-tier elimination, air conditioning for vehicles, and granting of the ML King Jr. federal holiday were clearly offered in the hope of pacifying the increasingly agitated workforce. In the end there are many other key issues including the all-important wage package. A substantial wage package that is overdue for many reasons, not the least of which is the galloping rate of inflation and the fact that UPS workers went all-out during the pandemic – with tens of thousands sickened and countless killed by the virus. Teamster members slaved non-stop during the pandemic but have received no bonus, no “thank you” compensation from the company for Covid-19 duty, no wage increases other than those negotiated 5 years ago when the rate of inflation was low. The expectations of the union membership are high, and they should be. The Teamster membership – now free of the corrupt misleadership of Jimmy Hoffa – appear to be ready to fight. New Teamster president Sean O’Brien led his campaign for President on the program of mounting a serious and sustained campaign to win not just a better contract at UPS, but a contract that would correct egregious past concessions from the Hoffa era – and take members forward in significant ways over the coming 5 years. All indications are – so far – that the O’Brien campaign to win a better contract at UPS is unfolding from coast-to-coast and is being greeted by members with great support and enthusiasm. BIDEN: STRIKEBREAKER IN CHIEF The UPS negotiations take place in their own category, much like the giant railroad labor battle of last year. Both struggles were exceptionally large in size and national in scale, especially in a U.S. labor scene that has seen the destruction of most large pattern-type union agreements. Rail and UPS both present the possibility of some national economic impact, and both have offered simple contrasts between greedy and profitable employers on the one hand, and angry union members on the others. While the UPS battle with the Teamsters may at first glance look like just a large scale but simple union-management fracas, in reality the entire corporate establishment will be in the UPS corner. Big business and its political hirelings are well aware of the danger – to them – of a Teamster win at UPS. And where will the Biden regime come down? Since Biden actively and publicly leaped into the railroad fray, wouldn’t it be reasonable to expect him to do likewise with UPS? In the case of the railroad labor negotiations, Biden cynically inserted himself personally, and by dispatching then-Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh to insinuate his way into the multi-union rail negotiations. From the start Walsh’s only role was to avoid a strike with the giant and profitable rail carriers. The outrageous situation of the rail workforce – gross overwork, virtually serfdom conditions owing to a lack of time off, safety issues, badly lagging wages – had to be subordinated so that Biden could avoid the alleged economic damage that would result should the workers be allowed to strike. (For background on the rail fight see my previous articles: “Lions Led by Asses” | MLToday and Learning from the Biden Strikebreaking | MLToday ) Biden and Walsh both systematically played politics with the rail fray. For several months both spoke out against strike as an option, never once supporting the struggle of the rail workers openly. Never once did the Biden regime denounce the greed and perfidy of the rail barons, never once sounded the need for active federal intervention on behalf of the workers’ struggle against this corporate outrage. With the active collusion of several of the 13 rail union Presidents, as well as the rail corporations themselves, in the end the strike momentum was derailed and deflated, and the unions were defeated. The rail strike had been several decades in the making, and an uncontested case exists that a national railroad strike was not only justified, but it was also overdue. With the anti-worker “bag job” completed, the Biden White House declared victory – for itself – and promptly abandoned the whole affair. The rail corporations gleefully celebrated while the exhausted and demoralized rail workforce was left to listen to Biden’s continuous claim that he is “the most pro-union President in U.S. history.” Throughout the entire rail labor drama, Biden emphasized over and over the “economic damage” that a strike by the 110,000 rail workers would do somehow to the national economy, even if the strike was short-lived. Of course, “the most pro-union President in U.S. history” apparently does not grasp the fact that strikes by their very nature are acts of last resort, and yes, are intended to damage the employer’s economic fortunes. Lost in the media reports of the rail debacle was the fact that the UPS showdown – then still at least 10 months off – involved a workforce 3 times as large as the combined rail union membership – and in many ways promised to be far more disruptive to the national economy. But the precedent was set and the question was posed; if Biden would crush the rail strike momentum of 110,00 union workers so brazenly, wasn’t it almost a sure thing that he would do likewise in the UPS fight? TEAMSTER MEMBERS ALSO BIGGEST BIDEN TARGET IN RAIL STRIKEBREAKING In a twist that is apparently unknown, it was the Teamsters Union that also bore the brunt of Biden’s strikebreaking in the railroad fight. Two unions: the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen (BLET), and the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way (BMWE), combined, represented a majority of the rail union membership. Both unions have been affiliates of the Teamsters Union for several decades. These rail “operating” members also faced the direst situations with the rail carriers draconian attendance regimes as these workers travel extensively and frequently away from home in their work assignments and essentially were on-call practically every day of the year. Likewise forgotten is the fact that the Teamsters Union has been an independent union for nearly 20 years, having quit the AFL-CIO as part of the Change to Win movement in 2005. With the AFL-CIO already unconditionally in Biden’s grip ( See; Top AFL-CIO Leaders Cast Their Lot with Biden | MLToday ) it will be of paramount interest to see how the Federation and its unions react as the increasingly frantic White House scrambles to recruit labor allies in advance of the UPS showdown. Teamsters President Sean O’Brien is well-aware that many of the AFL affiliate leaders will try to “have it both ways”, by telling the Teamsters they have their support and likewise telling Biden that they are in his corner. Many unions realize the key role of the Teamsters Union in their own employer fights, so outright abandonment of the Teamsters is unlikely. But the Teamsters will need to continue to be forceful with the slippery and weakling union leaderships all-too prevalent in the labor movement to prevent any significant public breach from developing. The role of the UPS company can be easily predicted, as it will do just about anything, and say just about anything, only needing to escape a strike. But it is almost a certainty that the Biden forces will continue to try to avoid or even sabotage a UPS strike – perhaps maneuvering that has already been underway for months. BEWARE BIDEN Despite the ravings of some Democrats, folks in the political industry enriched by this regime, and Biden labor bootlickers, the Teamsters dare not trust this President in the UPS battle as these facts attest. The months-long Hollywood Writers strike has elicited little apparent White House support – even rhetorical statements. As that strike began more than 3 months ago Biden said he hoped that the striking writers are given a “fair deal as soon as possible”. Lifted from the standard say-something-but-don’t-do-anything political playbook, Biden has not even dispatched his hapless-and-in-need-of-an-assignment Vice President Kamala Harris to Writers Union picket duty. Has the First Lady or Cabinet members been asked to show overt support for the striking writers? Of course not. The start of the far larger Screen Actors Guild strike now adds new pressure on Biden. Additional tens of thousands of union members are joining the picket line, also confronting the egregious corporate greed in their case by the entertainment overlords. Can Biden bring himself to carry a picket sign, even long enough for a cheap photo op? Can he bring himself to speak out clearly and forcefully against the corporations forcing these disruptions? Might the self-proclaimed “most pro-union President” find the time to stop by the Writers picket line, or the Screen Actor’s picket line, or any of the Teamster “practice pickets” now spreading across the country in front of countless UPS depots and garages? Will he? THE TALE OF THE TAPE A glance at the following video tape from just several years ago tells the tale. In an election eve scramble for Teamster votes and manpower in his 2020 election, Biden issued a message heaping praise on the Teamsters Union, and its soon-to-be exiled president Jimmy Hoffa. (A message from Joe Biden to the Teamsters https://youtu.be/SbECBQUd7Qw ) Praising the same Hoffa who systematically conceded all manner of work rules and two-tier schemes to UPS in previous negotiations. The same Hoffa who stood down at the last Teamster election certain in the full knowledge that his members would never re-elect him, led in large part by the giant UPS block of Teamster voters. The entire Biden message is for the members to support him in his election fight. Biden makes no mention of the rail strike then already taking shape, and certainly no mention of the inevitable UPS fight building even then. Almost 400,000 Teamster members work in UPS and the rail industry alone, but why bother to offer specifics about support that he would tender once the union was in need? THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE LEFT As the UPS contract deadline approaches on August 1st, pay close attention. A strike is not a certainty, and there may be a settlement, or an extension of time. But should the strike materialize, this will be the largest and most important labor battle for the past – or the next – 10 years. Now joined by more than 100,000 additional entertainment workers, by August 1 we may see nearly 500,000 union members on the picket line together. The Teamsters Union web site will include factual updates Front Page – International Brotherhood of Teamsters as will the web site of the Teamsters for a Democratic Union, (TDU), the leading member-driven militant caucus Teamsters for a Democratic Union (tdu.org) Labor Notes is also a reliable source. Labor Notes | The rail strike situation proved that the bulk of the news media are either incapable of telling the factual real story of a labor fight, or are systematically interested in twisting it for right-wing purposes. Many left outlets will do their best to follow the developments, but again, be careful and skeptical of the reports manufactured by the corporate media who have unhidden loyalty to UPS. Picket duty to support the Teamsters and the Hollywood workers, and other demonstrations of support will likely appear all-round. Anyplace where there is a UPS depot, garage, or UPS-run facility there will likely be a picket line on day one, August 1. That date may shift forward should there be an extension. It is critical that the company – and the Teamster members – see public support. The 1997 UPS strike 1997 United Parcel Service strike – Wikipedia lasted 15 days and was viewed as a major success. It also set a bar and goals that eventually led to the exit of Hoffa set the stage for today’s fight. The U.S. left, especially the labor left, has so far played a positive role in the UPS battle, and that must continue and expand. The outcome at UPS may influence more broad labor developments, particularly at Amazon. Young workers need also take particular interest as the shape of the future U.S. workplace will be influenced by the Teamster fight. WALSH POSTSCRIPT Left for last – where it belongs – is a postscript regarding the sorry and former Biden Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh. A smalltime union leader-turned-politician, Walsh rose from position to position always trading on his trade union credentials. Arriving eventually as the hand-picked Secretary of Labor in the new Biden regime, Walsh was endlessly ballyhooed as a remarkable figure, a “first”, an extraordinary union and political leader, on and on. Most major unions and the AFL-CIO praised Walsh at every turn, touting his union credentials, excited just at the thought that Biden would actually pick a union member for one – but only one – of his top spots. Where is Walsh today? The rail strikebreaking job was barely buried when Walsh abruptly resigned his position and took a multimillion-dollar job as the head of the Hockey Players Union. His supporters and worshippers were stunned and dumbfounded. As for real union members and working people, having seen his disgusting strike-breaking role during the rail negotiations, his role as special emissary from Biden to wreck the strike at all costs, Walsh now joins the ranks of exiled and discredited misleaders of labor, hopefully to be forever forgotten. AuthorChris Townsend is a 44 year trade union staff and organizer. He was the Political Action Director for the United Electrical Workers Union (UE) and was the International Union organizing and field director for the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU). He may be reached at [email protected] This article was produced by Marxism-Leninism Today. Archives July 2023 I will never forget the thick summer heat that filled the sanctuary of my rural Southern Baptist church when revival week came around. Once a year, we would host a traveling firebrand of a preacher to come and reignite the spark of our faith. The press of the bodies together in long wooden pews was in stark contrast to the normally cool, even austere atmosphere that usually occupied the space between the four walls we all held as holy. The world, even then, could often feel hopeless and cruel, but within that heat we felt transformed, energized, empowered by a truth we held together, by a faith in something greater than each of us that bound us together in a common cause. These revivals spanned several days and by the last few days, the size of the crowds held within that small space swelled to the point of spilling out of the several doors that offered entry not only to a place, but also to a process of rebirth. New faces popped up in the crowd. When our passions reached a fever pitch, many were brought to their knees, weeping and reaching out to grab hold of others; for support, for comfort, for connection. I couldn’t help but contrast these memories against my first union meeting with my UFCW local. It was held in a big hotel conference room in Irving, TX, difficult to reach with a car and impossible without one. I didn’t expect the same passion as those evening revivals; more like a healthy Sunday congregation. To my shock, I realized I was only one of three workers at our union meeting, as opposed to five times that number of staffers sitting in the back! The meeting was never formally called to order and the President spoke informally, attempting to answer the acute frustrations workers had trying to navigate the crushing bureaucracy of our health insurance program. I was told our local had no buttons, shirts, hats, masks, or anything else to provide us that we could wear at work to show our union pride. But if a union meeting is closer to a routine Sunday at church, could that mean the upcoming national convention will be our revival? Delegates from across the country will converge in late April as the highest constitutional authority of UFCW. Will those delegates feel the same living heat that I felt so many years ago, each knowing deep in their hearts that the sum of each person bound together in a righteous cause is far greater than each individual part? It will be impossible for me to know; the leadership of my Local 1000 chose to reject the opportunity to send 14 delegates to the convention. Instead, they chose only to send two delegates, the President and the Secretary-Treasurer. Not one single rank and file worker will be in attendance in April. No one will return to the shop floor to testify to their convention experience. If there is any heat, apparently it is only for the officers to know. We must defer to our High Priest of Labor. Perhaps I am simply naive. It is easy (and not without reason) to look back on these raucous summer revivals through those cynical eyes, to reduce them to nothing more than the orchestrations of self-serving demagogues preying on the emotions and insecurities of faithful country folks. Or to see ourselves in the crowd, tears streaming down our faces and our hands held towards heaven, as knowing but unadmitted participants in our own manipulation. Across all sectors of society - church, school, unions, government - the refrain has become: “Only suckers have hope. Only fools have faith. It is not God that is dead, but ourselves. Only those who believe in nothing know the truth. Embrace the liberation of low expectations and you will never know the crushing disappointment that has defined our last half century.” I have long since left behind the revival days of my childhood church. I understand the cynicism; I even share it for the most part. We have all seen the stream of news reporting the corruption of many of our pastors and our union leaders. Are we to simply bury our heads in the sand, a nation of pollyannas who know better than to rock the boat? And even though such disappointments hold true, can we say they are the whole truth? It is just as true that in the holy place of my childhood sanctuary, we felt alive together, bound together, energized to fight together. The truth is that we shared a truth together and it gave us life, hot as fire and electric arcing across the hands stretching towards the ceiling. I refuse to lose faith that such an ember exists within our labor movement; a burning truth that binds us together. I have a defiant faith that the world we deserve can only be built with working hands. Against the sea of despair we have been blessed with the duty to protect this ember and with our labor, we must wage a struggle to turn back that rising tide so the fire of revival can catch and spread across our nation. The barn-burning sermons came to an end and the tear-streaked faces always left that sanctuary. We were convinced we were prepared to fight for our families, for our values, for our communities. Yet despite our deepest convictions, we watched our families broken and buried under financial stress and instability. Our values were warped in service to a real and dangerous demagoguery lurking behind the scenes, one that whipped our passions to set us against people we saw as different from us. Our schools were looted of resources and left to rot, transformed into sites of culture wars and shooting wars. Those hot nights were not enough to save us and it broke my heart. I have only felt it a few times since then: pressed into a crowd of hundreds screaming through chain link fencing at the Klansmen arrayed across the lawn of our county courthouse or circling a picket line as summer heat beat down on smiling, chanting faces. Similar experiences have been few and far between. For decades now, working people have been hammered by big money. It has destroyed many things, our wages and living standards, our lifespans, the safety of our communities, our hope for the future. But most devastatingly, it has destroyed our faith in ourselves and each other. It has destroyed any respect working people have for ourselves, pressing our heads beneath the biting waters of despair and self-loathing. Big money and its payroll of political goons have killed the spirits of working-class people all across this country, regardless of color, or faith, or sex, or sexuality, or anything else. It has been both indiscriminate and comprehensive in the spiritual violence it has inflicted upon every single person who works for a living. It is against this backdrop of spiritual death that those summer nights have been calling to me. What can be the only response to such a comprehensive death but rebirth? How else can we answer death but with new life; with a revival? This revival is not a dream; it is already unfolding all around us. It has caught the spirit of baristas, teachers, autoworkers, and those risking injuries across the countless warehouses that dot the country. It is the engine that drives reform within the UAW and the Teamsters today, and my union, UFCW, tomorrow. Only a labor revival, across all faiths, all races, all working people, can we regain the fighting spirit that has been crushed out of us. Revival alone, bound together in the heat of a common purpose and guided by a common truth, can give force to the fight to save our families and our communities. Only a revival of the fighting working-class spirit can save our nation from the forces of financial greed. AuthorBradley Crowder This article was republished from Kroger-Workers' Voice. Archives June 2023 Workers at Blue Bird Corporation in Fort Valley, Georgia, launched a union drive to secure better wages, work-life balance, and a voice on the job. The company resisted them. History defied them. Geography worked against them. But they stood together, believed in themselves, and achieved a historic victory that’s reverberating throughout the South. About 1,400 workers at the electric bus manufacturer voted overwhelmingly in May 2023 to join the United Steelworkers (USW), reflecting the rise of collective power in a part of the country where bosses and right-wing politicians long contrived to foil it. “It’s just time for a change,” explained Rinardo Cooper, a member of USW Local 572 and a paper machine operator at Graphic Packaging in Macon, Georgia. Cooper, who assisted the workers at Blue Bird with their union drive, expects more Southerners to follow suit even if they face their own uphill battles. Given the South’s pro-corporate environment, it’s no surprise that Georgia has one of the nation’s lowest union membership rates, 4.4 percent. North Carolina’s rate is even lower, at 2.8 percent. And South Carolina’s is 1.7 percent. Many corporations actually choose to locate in the South because the low union density enables them to pay poor wages, skimp on safety, and perpetuate the system of oppression. In a 2019 study, “The Double Standard at Work,” the AFL-CIO found that even European-based companies with good records in their home countries take advantage of workers they employ in America’s South. They’ve “interfered with freedom of association, launched aggressive campaigns against employees’ organizing attempts, and failed to bargain in good faith when workers choose union representation,” noted the report, citing, among other abuses, Volkswagen’s union-busting efforts at a Tennessee plant. “They keep stuffing their pockets and paying pennies on the dollar,” Cooper said of companies cashing in at workers’ expense. The consequences are dire. States with low union membership have significantly higher poverty, according to a 2021 study by researchers at the University of Minnesota and the University of California, Riverside. Georgia’s 14 percent poverty rate, for example, is among the worst in the country. However, the tide is turning as workers increasingly see union membership as a clear path forward, observed Cooper, who left his own job at Blue Bird several months before the union win because the grueling schedule left him little time to spend with family. Now, as a union paper worker, he not only makes higher wages than he did at Blue Bird but also benefits from safer working conditions and a voice on the job. And with the USW holding the company accountable, he’s free to take the vacation and other time off he earns. Cooper’s story helped to inspire the bus company workers’ quest for better lives. But they also resolved to fight for their fair share as Blue Bird increasingly leans on their knowledge, skills, and dedication in the coming years. The company stands to land tens of millions in subsidies from President Joe Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and other federal programs aimed at putting more electric vehicles on the roads, supercharging the manufacturing economy, and supporting good jobs. These goals are inextricably linked, as Biden made clear in a statement congratulating the bus company workers on their USW vote. “The fact is: The middle class built America,” he said. “And unions built the middle class.” Worker power is spreading not only in manufacturing but across numerous industries in the South. About 500 ramp agents, truck drivers, and other workers at Charlotte Douglas International Airport in North Carolina also voted in May to form a union. Workers in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 2022 unionized the first Starbucks in the South. And first responders in Virginia and utility workers in Georgia and Kentucky also formed unions in early 2023, while workers at Lowe’s in Louisiana launched groundbreaking efforts to unionize the home-improvement giant. “I wouldn’t hesitate to tell any worker at any manufacturing place here that the route you need to take is the union. That’s the only fairness you’re going to get,” declared Anthony Ploof, who helped to lead dozens of co-workers at Carfair Composites USA into the USW in 2023. Workers at the Anniston, Alabama, branch of the company make fiberglass-reinforced polymer components for vehicles, including hybrid and electric buses. Like all workers, they decided to unionize to gain a seat at the table and a means of holding their employer accountable. Instead of fighting the union effort, as many companies do, Carfair remained neutral so the workers could exercise their will. In the end, 98 percent voted to join the USW, showing that workers overwhelmingly want unions when they’re free to choose without bullying, threats, or retaliation. “It didn’t take much here,” said Ploof, noting workers had little experience with unions but educated themselves about the benefits and quickly came to a consensus on joining the USW. “It’s reaching out from Carfair,” he added, noting workers at other companies in the area have approached him to ask, “How is that working out? How do we organize?” As his new union brothers and sisters at Blue Bird prepare to negotiate their first contract, Cooper hopes to get involved in other organizing drives, lift up more workers, and continue changing the trajectory of the South. “We just really need to keep putting the message out there, letting people know that there is a better way than what the employers are wanting you to believe,” he said. AuthorTom Conway is the international president of the United Steelworkers Union (USW). This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute. Archives May 2023 3/28/2023 LA Schools’ Lowest-Paid Workers Walk Out, With Teachers by Their Side By: Sonali KolhatkarRead NowA massive three-day strike by school support staff and teachers recently shut down Los Angeles schools. They stand together to demand better wages and benefits for the school district’s most vulnerable workers. Tens of thousands of Los Angeles teachers went on strike March 21-23, 2023, for the first time in four years, shutting down the nation’s second-largest school district for three rain-soaked days. But this time the United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA) did not walk out in order to demand better working conditions for educators. Rather, they were engaging in a remarkable act of solidarity with their lesser-paid colleagues—the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD)’s support staff of about 30,000 people who are in their own union, Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 99. It was the first time that the two unions—the largest two in Los Angeles—went on strike together. SEIU Local 99’s demands for the district to offer a 30 percent pay raise and health benefits may sound ambitious. But that’s only because the district’s campus aides, teaching assistants, cafeteria workers, bus drivers, gardeners, and other support staff make an average of only $25,000 a year with no benefits. In Southern California, where everything from housing costs, to health care, to groceries are far higher than the national average, this is an untenable wage. Although LAUSD is offering the workers a 23 percent salary raise along with a 3 percent bonus, the double-digit bump is not nearly enough to make ends meet relative to the appallingly low wages they currently earn. On March 23, 2023, the third and final day of the three-day action, thousands of workers gathered in Los Angeles State Historic Park for a final joint rally. Among them was Maria, a campus aide at Eagle Rock High School, who spoke with me and preferred not to use her last name. She tells me, “we live paycheck to paycheck, and we have to work some days unpaid on top of it all.” Suraya Duran, a community parent representative at Eagle Rock High School and member of SEIU Local 99, was also at the rally. She says, “These essential employees worked through the pandemic with no raise, no benefits, and the uncertainty of stable hours.” In contrast, Duran points out, “it’s egregious to hear that the [school] superintendent makes more than the president of the United States.” She’s referring to LAUSD’s latest head, Alberto Carvalho, who makes $440,000 annually, the most that’s ever been paid to a district superintendent in LA. It’s not as if the district can’t afford to pay its lowest-paid workers a living wage. It currently has at its disposal a $4.9 billion reserve fund, of which about $2.3 billion has not been spoken for. The unions argue that this money can and should be used to meet worker demands for higher wages. “There is money. It’s whether they choose to invest in these workers. That’s the bottom line,” says Duran. Superintendent Carvalho spun the strike to suggest the workers were letting down low-income students of color by walking out for three days. He released a statement on Twitter the day before the strike began, saying that the COVID-19 pandemic was particularly difficult for “kids who are English language learners, students in poverty and students with disabilities,” who “cannot afford to be out of school.” But Duran, whose job involves liaising between a school and parents, points out that many of the support staff’s own children attend schools in LAUSD. She says that it is common for workers to juggle multiple jobs in order to make ends meet. “They come to the school during the day, and then they’re going to a graveyard shift.” She adds, “They deserve to have a wage that is comparable to today’s standards.” Maria says, “I feel that we are underpaid, and we feel unappreciated by the district. We are the ones that get paid less, but we are the ones that make sure the campus is safe, and, most important, that the kids are safe.” The public generally considers educators as the only school workers worthy of compensation. The strike served to uplift the voices of support workers like Maria who often remain invisible, but whose jobs are essential to the functioning of schools. UTLA secretary Arlene Inouye pointed out in an op-ed that “24 percent of SEIU 99 members report that they don’t have enough to eat. One in three report that they have been homeless or at high risk of becoming homeless while working for LAUSD.” This underscores the injustice of a district sitting on more than $2 billion while relying on severely underpaid workers to continue operations. If Carvalho is so concerned about children living in poverty, he could directly address some of that by meeting the wage demands of their parents who work in the district. Instead, he ridiculed the unions in a now-deleted Tweet that SEIU Local 99 captured in a screen grab. “1,2,3…Circus = a predictable performance with a known outcome, desiring of nothing more than an applause, a coin, and a promise of a next show,” wrote Carvalho in February 2023 after the strike was announced. He added, “Let’s do right, for once, without circus, for kids, for community, for decency.” But strikes serve the explicit purpose of moving the ramifications of closed-door negotiations out into the open for all to see. Perhaps it is the visibility of LAUSD’s refusal to meet the wage demands of its lowest-paid workers that Carvalho most objected to when he referred to the strike as a “circus.” The UTLA-SEIU joint strike served a powerful narrative purpose: to highlight the appalling working conditions of tens of thousands of workers in LA public schools and to warn the district that workers have each other’s backs. Although SEIU workers and their UTLA colleagues returned to school campuses after their three-day walkout, the district has, as of this writing, remained firm on its lowball offer. However, the strike did prompt LA’s newly elected mayor Karen Bass, who initially remained on the sidelines, to get involved. Bass is now actively mediating between the district and unions. Alejandra Sanchez, a special education assistant at Eagle Rock High School, has a message for the superintendent: “Mr. Carvahlo, we are not ‘clowning around’ as you implied [in your tweet]; we are here today as one, UTLA and SEIU, fighting together for a better future, for respect, better wages, and stable hours. Our work is not a joke.” Highlighting the solidarity between teachers and support staff and their refusal to stay silent, one teacher at Sanchez’s school wore a rain poncho while picketing that sported the words, “Hey Carvalho, in our ‘circus,’ you’re the saddest clown.” AuthorSonali Kolhatkar is an award-winning multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host, and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. Her forthcoming book is Rising Up: The Power of Narrative in Pursuing Racial Justice (City Lights Books, 2023). She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and the racial justice and civil liberties editor at Yes! Magazine. She serves as the co-director of the nonprofit solidarity organization the Afghan Women’s Mission and is a co-author of Bleeding Afghanistan. She also sits on the board of directors of Justice Action Center, an immigrant rights organization. This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute. Archives March 2023 3/26/2023 Starbucks workers take nationwide coffee break and walk off the job. By: Mark Gruenberg, John Bachtell, Roberta Wood & Scott MarshallRead NowStriking Starbucks workers took the lovable skeleton mascot out of the closet where their bosses had confined it, saying the skeleton was treated as badly as the workers. | Roberta Wood/PW CHICAGO — How did Marvin, a lovable skeleton, become the mascot of striking Starbucks workers in this city’s historic Greektown neighborhood? This location is blocks north of the giant University of Illinois campus. It is one of more than a hundred stores in the country where the workers filed for union representation and voted to join today’s strike, even before the NLRB had a chance to schedule their union recognition vote. According to the baristas here, management’s treatment of Marvin corresponds to their treatment of the workers and their community. Marvin “came to life” one year during the Halloween season when workers hung Marvin in the window, and he became a neighborhood fixture, decked out to celebrate whatever holiday was going on, bringing smiles to the faces of both staff and community. “But then Starbucks District Manager Lesley Davis said we couldn’t have him,” explained Chris Allen, 22, a shift supervisor. Davis banished the beloved Marvin to the back of the house, out of sight. “It sucks having someone else make all the decisions when you’re doing all the work daily,” Lily Haneghan, 23, told People’s World. Haneghan admitted when co-workers first discussed forming a union, she was scared. “I had no idea what a union was, and then my boss said, ‘If you unionize, you will get fired.’” That was a big threat to someone who had invested the last five years of her young life working for the company. But then she reflected, “They think of us as coffee robots. There’s no concern for our physical and emotional well-being.” Haneghan and Allen were co-strike captains.

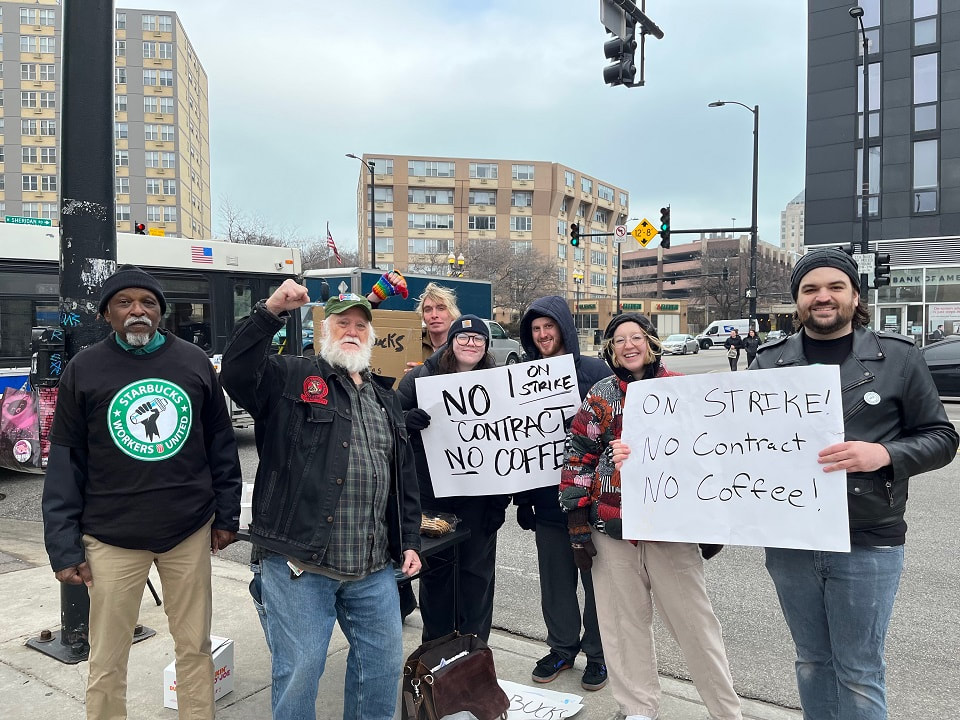

The national Starbucks strike on March 22, at more than 115 stores from Anchorage and Arkansas to Seattle and Phoenix, preceded the showdown at the firm’s annual meeting over whether its union-busting is hurting the so-called progressive coffee chain’s brand. The baristas and their allies walked out to protest the firm’s rampant labor law-breaking, orchestrated and directed by longtime CEO Howard Schultz. The labor law-breaking prompted union pension funds and pro-stockholder investors to demand an independent audit of the impact of the law-breaking, which also defies the firm’s proclaimed standards. The proposal came up at its Zoomed annual meeting on March 23. “The faux progressivism of Starbucks is being exposed for what it is: A marketing ploy,” said Starbucks Workers United (SWU), the union-sponsored group aiding the grass-roots organizing drive nationally. The National Labor Relations Board filed federal charges against Schultz personally and over 500 charges it levied against the company. The number of complaints from exploited Starbucks workers to the NLRB is 1,200 and counting. “The One Day Longer national unfair labor practices (ULP) strike demanded Starbucks fully staff all stores, give partners a real seat at the table, not an empty chair, and negotiate a contract in good faith,” SWU said. That’s exactly what Schultz, his union-buster lawyers, and his managers haven’t done. The only two bargaining sessions the two sides ever had—after pressure on Schultz—lasted five minutes each, with the bosses, led by the union buster, walking out.

More than six years with Starbucks Sean Plotts has worked six and a half years for Starbucks, including two and a half years as a shift manager at the Lincoln Village location in Chicago. A recent graduate, he holds an associate in arts degree from McHenry County College. “They were once cutting edge in the fast food industry, but other companies have caught up. They are brutally cracking down on stores going union,” said Plotts. Less than 300 stores are unionized out of 28,000, and 900 unfair labor practices are already filed with NLRB. “All we’re asking,” Plotts said, “is to be treated fairly, paid well for our services, and given the resources to serve the public. We love this job, but it’s stressful when they’re cutting hours and cutting floor coverage to save a couple of extra bucks at the end of the day.” Plotts described this as a “union-busting” tactic, adding, “They want to flush out many tired employees. We’re all tired. People shouldn’t have to work as long as they do for little pay just so the stores can get a couple hundred more dollars at the end of the day.” So far, Starbucks refuses to recognize the union at the Lincoln Village location. “We’ve had one bargaining session which lasted eight minutes, including introductions,” said Plotts, who expressed gratitude for public support for the strikers. Shot the hours back Another Lincoln Village worker, Autumn Graham, who sports shoulder-length hair, has been with Starbucks for five years. He started in St. Louis and moved to Chicago because of a toxic work environment at the store there. “I worked at a store on Bryn Mawr Avenue (in Chicago),” he said. “We unionized in May, and they shut us down in October. We and the Clark and Ridge store were the first to organize in Chicago. They just stonewalled us. Cutting our work without telling us anything and then shutting it down and assigning us to other stores. Graham depends on Starbucks’ health benefits, as meager as they are, and needs to work full-time to pay his bills. The company has slashed his hours, making life difficult. “If you work 20 hours, you get benefits. Many workers struggle to get to 20, only get 17, and are denied benefits. When we unionized, they cut our hours from 20-25 to 15 hours and denied us benefits,” he said. “Recently, they shot the hours back up because we’ve lost a lot of staff. They say business is slow, but I know from the receipts that we’re as busy as before. They ask us to do more with fewer people,” said Graham. “If you’re a Starbucks customer, just fill out the review on your receipt and write ‘support the union, come to the negotiating table,'” he said. “They need to quit making excuses.” Across the country, workers in 24 stores in California—including two in Sacramento and one each in Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—joined them. Back East, so did workers in Boston, six stores in metro D.C., three in the Baltimore area, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit and Flint, Mich., Buffalo, St. Louis, and St. Paul, Minn., among others. “As Starbucks celebrates their provenance and record profits this week, my partners have to deal with the reality that we are being nickeled and dimed to extract as much labor as cheaply as possible,” said Maria Flores of Queens, N.Y. “Our shift supervisors, who make maybe $4 more an hour than baristas, are being met with resistance when picking up barista shifts or working with other shift supervisors, and they’re struggling. Where is the disconnect? “I’m striking because the power of workers can save the world. Our union is small but now unstoppable, and we’re ready to start making moves. The walls are closing in on Starbucks and when we negotiate I think the flood gates might open!” “Workers unite!” her Queens colleague James Carr predicted. “I’m excited to get out onto the streets with the people, enjoy the weather, and withhold my labor from Starbucks.” “I’m excited to join the national effort in striking! It’s so reassuring and reaffirming to be a part of something that’s bigger than just Long Island. I hope Starbucks corporate starts accepting and joining us in solidarity,” said Lynbrook, L.I., worker Liv Ryan. The workers and SWU have won union recognition elections at 294 Starbucks stores and file daily for votes at more stores. The latest unionized stores are in Oak Park, Ill., at Lake St. and Euclid, plus Pleasanton and Sunnyvale, Calif., Ashland and Portland, Ore.—at Portland State University, and Cameron, N.C. Its latest wins were in Portland, at the Pioneer Courthouse, at 10th and Market Streets in downtown Philadelphia, at Litchfield Park, Ariz., and in Hillsboro, Ore.