|

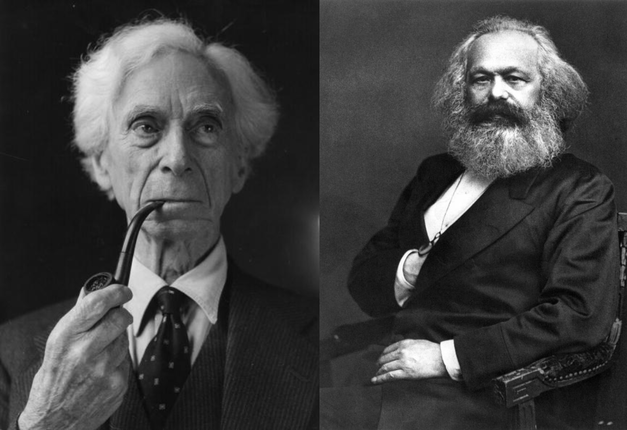

Bertrand Russell discusses the philosophy of Karl Marx in chapter 27 of his A History of Western Philosophy (HWP). He begins by telling us he is not going to deal with his economics or politics, just his philosophy and its influence on others. While Lenin saw Marx’s philosophy as developing from three sources— British economic theory, early French socialist thought, and classical German philosophy (Hegel) Russell sees only two sources. Marx’s philosophy is the “outcome” of “the Philosophical Radicals (mostly British) and French materialism. He credits Marx with a broad outlook, at least with respect to Western Europe where he shows “no national bias.” But, Russell says, it’s not the same regarding Eastern Europe because “he always despised the Slavs.” A comment about this. This meme about the Slavs was widespread in anti-Marxist and anti-Soviet propaganda (and still is) in the time of the writing of the HWP. It has no basis in fact. Marx and Engels made highly critical, even derogatory, remarks about some groups of Slavs in the Austrian Empire who fought on the reactionary Austrian aide in putting down the progressive forces leading the 1848-49 pan-European anti-feudal revolution. But they were in full support of the Polish revolutionaries at that time, and later supported the progressive revolutionary forces that were developing in Russia. After this maladroit observation, Russell continues in a more positive vein. He does mention economics, saying Marx’s economic philosophy is an outgrowth of classical British thought on this subject, in agreement with Lenin. There is a difference, however, the British economists wrote in defense of the up and coming industrialists and were opposed to the interests of the agriculturalists and the laboring classes. I should mention, though, that Adam Smith did have a lot to say in defense of the laboring classes and criticized their treatment by the up and coming industrialists. Marx, on the other hand, was completely on the side of the wage-earners. He never relied on emotional appeals when he laid out his theories and, Russell says, “he was always anxious to appeal to evidence, and never relied on any extra-scientific intuition.” Russell next discusses Marx’s “materialism”. It’s not the mechanical materialism of the French enlightenment. In which external objects react on a passive human consciousness. Russell points out that under the influence of Hegel, Marx’s materialism is an interaction between the subject and object in which both are changed — it’s what’s meant by the term “dialectical.” Russell says this view is similar to what non-Marxists refer to as “instrumentalism”. This will not do. It is too subjective as instrumentalism, a form of pragmatism, judges the truth of a statement by its usefulness— true statements do not necessarily relate to some objective x in-itself but they are statements that are useful for our future actions and ability to understand or control reality as it appears to us. Let’s deconstruct the following quote. “In Marx’s view, all sensation or perception is an interaction between subject and object; the bare object, apart from the activity of the percipient, is a mere raw material, which is transformed in the process of becoming known”. The problem with this is that it reeks of Kantianism. The raw material is the thing-in-itself which is transformed by perception into the thing-for-us. The mind is much too active here. Marxists have used the analogy of a mirror in discussing the relation of subject and object— perception is a “reflection” of the external world. Perception doesn’t change the object. The mind is not totally passive as experience is the collection of all our perceptions and the mind has to order and evaluate them so as to understand the world it reflects. The world itself is in constant motion and change. The concept of “dialectics” is used to describe this aspect of reality, it doesn’t impose dialectics on the objects, it reflects the workings of the objectively existing dialectical motions exhibited in the external world. There is no spoon bending telekinesis going on. Russell gives a long quote from Marx ending with “Philosophers have only interpreted the world but the real task is to alter it.” It’s a quote from his Theses on Feuerbach. It’s a famous quote, but it is beside the point regarding the transformation/reflection theories of perception as acting on our percepts to change aspects of external reality follows from either theory. Russell next asserts that “It is essential to this theory [Marxism] to deny the reality of “sensation” as conceived by British empiricists.” This empiricist conception of ‘sensation” was a revolutionary new development, Russell says, introduced into philosophy by John Locke (1632-1704). The mind is originally a blank slate (tabula rasa) and all our ideas are based on sensations as input from the five senses (experience, perception) which are then put into order by an internal power of the mind or “reflection” (our thoughts, and ideas) called internal perception. There are no innate ideas. Russell admits both empiricism and idealism have technical philosophical problems that are still today unresolved. This stems from a view that external objects have some kind of unchanging essence that the brain passively accepts and then fools around with by means of reflection. He says Marx has a more activist view of the interaction between the world and the brain, but he won’t discuss this further in this chapter but will deal with it in a later chapter. That turns out to be the chapter on Dewey and his view of “instrumentalism” mentioned above. Russell says that Marx didn’t spend a lot of time on these concerns and so he intends to move on to Marx’s views on “history.” Russell tells us that Marx’s philosophy of history is a “blend” of Hegel plus classical British economy. He takes the dialectic from Hegel but interprets it materialistically not idealistically as Hegel does. He tells us that the “matter” in Marx’s version of materialism is “matter in the peculiar sense that we have been considering, not the wholly dehumanized matter of the atomists.” It’s true that Russell was describing a “peculiar” kind of matter above when discussing perception as a “mutual” interaction between subject and object, but he is wrong in saying this was Marx’s view. Matter is the objectively existing material world that exists whether humans exist or not— it was here before humans evolved and will be here when humans are extinct. But while we are here, we have to understand it to survive and prosper and science is the best method we have found to do so. Philosophy prospers when it incorporates the findings of science, religion when it ignores or denies them. Russell next takes up Marx’s “materialist conception of history”. Basically, the main features of the art, religion, and philosophy (and culture in general) of any epoch are “the outcome” of the economic mode of production and distribution by which society maintains and reproduces itself. I think Marxists would prefer “conditioned by” rather than Russell’s “the outcome of”. Russell only accepts some of the features of this view which he adopted in writing the HWP, but he rejects the thesis “as it stands.” He will illustrate what he means by considering Marx’s thesis as applied to the history of philosophy. All philosophers think their philosophy is “true”. No one would bother to write philosophy if they thought it was just some time-conditioned ultimately irrational product of their particular environment and not objectively but just subjectively “true”. He says, “Marx, like the rest, believes in the truth of his own doctrines; he does not regard them as nothing but the expression of the feelings natural to a rebellious middle class German Jew who was born in the middle of the nineteenth century.” So, what can we make of this? Well, Russell does think the ideas of an epoch do generally reflect the socio-political background— those of Aristotle and Plato were “appropriate” to city states, the Stoics to “cosmopolitan despotism,” medieval scholasticism to the Catholic Church, those of Descartes and Locke to “the commercial middle class” and Marxism and Fascism to the modern industrial State. Russell believes this to be important and true. The above seems like a form of elementary Marxism that hasn’t really been thought out very well. Nevertheless it’s the part of Marx that Russell says he gets. He does, however, say there are two major objections he has to Marxism. First, Russell rejects economic determinism as he thinks “wealth” is less important than “power” as the motivating force of history. Since he has already written a book about this (Power, 1938) he refers us to it and will not deal with this topic here. Neither will I, as Marxism is not based on economic determinism which is trotted out by anti-Marxists in order to refute a misinterpretation of Marxism and think Marxism itself has been refuted. Second, having disposed of “economic determinism”, Russell looks at other theories of “social causation” used to explain history; he doesn’t exactly mention any by name but wants to argue that personal reasons, temperament, emotional attachments, etc. make any general theory of social causation moot. He picks some very special technical issues in philosophy (the problem of universals, the ontological argument, the truth or not of materialism) and says, contra Marx, that he thinks that it’s a waste of time to look for economic reasons to explain the positions of the different philosophical opinions on these issues. Marx would agree. Marx would agree because his sub/super structure distinction, that the laws, values, moral outlooks, art, religious views (the superstructure of ideas and institutions) are in general conditioned by the physical environment people inhabit which affects how they make their living— obtain food, social wealth, living arrangements, etc. (the substructure). People living in a Stone Age environment are not going to build the Empire State Building. A Gothic cathedral is not going to be built by animists. The superstructure also feeds back influences on the substructure so there is mutual interaction between them. Marx never advocated the simple one-way determinism or social causation which upsets Russell. As far as “materialism” goes, the following comments should cover Russell’s views. 1) Russell says the word has many meanings, but he has shown above that Marx “altered” the traditional meaning. I already pointed out how Russell was in error about this. 2) The problem with using this word is that people have “avoided” defining what they mean by it. 3) Depending on the definition materialism can be a) proven to be false, b) may be true but “there is no positive reason to think so”, c) there are some reasons to believe it, but they are not conclusive. Since b and c are basically the same there are just two responses needed. Response to 2. In Marxism the distinction between Materialism and Idealism boils down to the view about the existence of external objects— does the Universe depend upon the existence of the human brain and consciousness in order to exist or is it independent on the human consciousness and existed before there were any conscious beings or ideas at all— say at the time of the “Big Bang” and the millions and billions of years before any type of life at all emerged in the universe? If you believe the Universe and matter (the quarks, photons, etc.,) existed before humans then, for a Marxist, you are a materialist. If you believe there was some great big Consciousness before the Big Bang, and it caused the Big Bang (and waited around 13.5 billion years or so before deciding to make humans or whatever) you are not. Response to 3. Russell says Big Bang Materialism may be true “but there is no positive reason to think so.” I think the modern results of the scientific view of the origin of the Universe are positive enough. It may be the case that the science of the future replaces the “Big Bang” with a different explanation, but I don’t think the replacement will claim that the Universe was dependent on humans. There are two “different elements” referred to by the word “philosophy.” One involves scientific knowledge and technical expertise in which a great deal of mutual agreement is possible. The other is the social area where the ruling element is “passionate interest” and reason takes a backseat— here is where, Russell says, Marx’s insights are “largely true.” Author Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. He is the author of Reading the Classical Texts of Marxism and Eurocommunism: A Critical Reading of Santiago Carrillo and Eurocommunist Revisionism. Archives June 2023

2 Comments

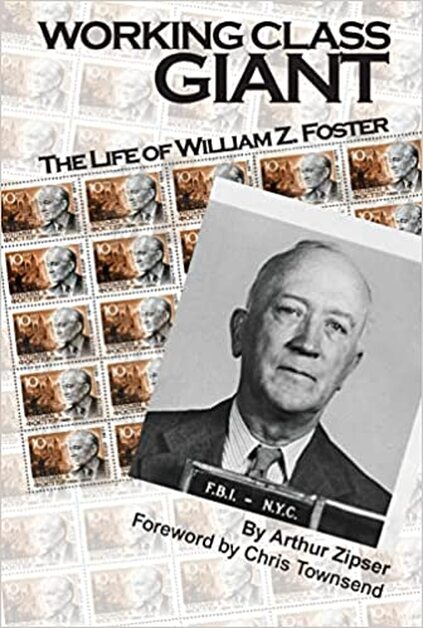

As the Communist Party of the United States entered the fourth full year of the Great Depression in 1933, its leadership recognized that a major consolidation and refocus of Party effort was necessary to reach the vast potential of the moment. The communist movement had been established in the U.S. for 15 years by that point, and some advances had been made in rooting the Party in certain key sectors – but not in others. The left and socialist organizations were all growing amidst the Depression conditions as the tempo of the class struggle increased daily. Turmoil among unemployed workers, small farmers, and veterans was beginning to approach a mass scale, and the battered trade unions had begun stirring in scattered and desperate strikes in opposition to wage cuts and employer assaults. Rightists, fascists, and militarists of every stripe likewise emerged in the economic collapse, tapping ruling class and mass working class discontent alike. Carbon copies of this process were unfolding world-wide. Something big was in the works, but what? A shift to the left? Or the right? Was another world war coming? Where was the United States going? What was ahead for the left? Would it be able to play a serious role in the fast-changing political and economic situation? The Extraordinary Conference Faced with this situation of both extreme threats and opportunities, the Communist Party opted to self-critically examine the actual state of things in its organization and work. Following a directive by the Communist International to conduct this “taking of stock”, parties across the world made the difficult self-assessment. The process that unfolded here in the United States culminated in a national Extraordinary Conference of the Communist Party that convened in New York City in early July 1933. Every facet of Party work, leadership, and membership was critically dissected to prepare for the Conference. What was the real size and composition of Party forces? What was the condition of their actual organizational and political activity? What was working, and what wasn’t working? Was there growth, or not? Why not? What did the membership really amount to, both geographically and industrially? How many were in the unions? In what areas of activity had the Party fallen short, or failed? What was the actual measure of the influence of the Party at that moment? How effective was the leadership? Were new priorities needed? Were previous leadership decisions being carried out, or not? Was new leadership needed? A rapid yet expansive and comprehensive inventory and inspection was made to determine what was really happening on the ground, top to bottom, in real numbers. Fuzzy claims and guesswork were discarded in favor of clear fact-based assessments. ( (For those seeking background on the 1932 and 1933 period see Philip Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Volume 11, The Great Depression and William Z. Foster, The History of the Communist Party of the United States, both from International Publishers. A Party Only on the Margins The 350 delegates who eventually took part in the 1933 Extraordinary Conference travelled to New York City with their heads spinning. They had much to consider as such a process had never before been attempted on such a scale. There was no escaping the fact that while the Party had made progress, and membership had increased markedly in the early Depression, the rate of progress, and the depth of the progress was insufficient to take advantage of the tremendous openings presented under the new conditions. Mistakes, miscalculations, and failures were chronicled. Some success was noted, but not nearly enough. Overwhelmingly the preparatory work and the Conference deliberations themselves revealed and concluded that the Party was still not growing and expanding in major ways. But why? Tremendous efforts were being made, some truly valiant and self-sacrificing. The answer to these questions became self-evident as a result of the work done to arrive at the Extraordinary Conference: insufficient effort, sometimes no effort had been conducted to root the organization in the working class, in the industries, in the workplaces, and in the unions. While all manner of good works and activities were being carried out by Party members and leaders in many fields, the Conference zeroed-in on the undeniable fact that the focus of the vast majority of its activity was far, far, removed from the workplaces and the trade unions. Too much priority was being placed on struggles removed from the centrality of the workplace and the working class that comprised the natural constituency of a mass socialist party. The Communist Party existed largely in the margins of U.S. political life, with no roadmap into the mainstream. Facing this fact meant confronting it, explaining the error, and redirecting the new and greatly unified Party work. This work was intended to bring not just membership growth in numbers, but in quality. Growth needed to occur in places likely to position the Party for potential mass growth among workers as the Depression continued to worsen. At its conclusion the Conference issued a broadside to the membership, an “Open Letter”, explaining that business as usual, the same routine, just putting one foot in front of the other, all these failed approaches had to be cast aside. Foster Endorses the Renewed Direction William Z. Foster recalled that the Extraordinary Conference “…addressed an Open Letter to the Party, outlining a program of militant struggle, stressing the need to concentrate upon building Party units and trade unions in the basic industries and to give all support to the growing mass strike movement. …(The Extraordinary Conference) …played a vital role in preparing the Party for the big mass struggles.” While not long the “Open Letter” issued by the Conference was distributed in massive quantities to all corners of the Communist Party membership and among supporters and contacts. An open letter to all members of the Communist Party, The Daily Worker of July 12, 1933, featured a front-page headline and article regarding the Conference, blaring that “Communist Party Holds Extraordinary National Conference to Strengthen Work in the Factories and Trade Unions”. The next day the Daily Worker published the entire text of the Open Letter to inform the membership and trigger discussion. For many months after the Conference, Party publications and cadre repeated the drumbeat; “Into the factories, into the unions!” There was unity on a scale never before seen. It wasn’t unanimous, or monolithic, but large sections of a national organization were moving in the same general direction. For a change. he effect of the Open Letter was immediate and electrifying. The preface of the letter explained that “This Extraordinary Conference and the Open Letter are designed to rouse all of our resources, all of the forces of the Party to change this situation, and to give us guarantees that the essential change in our work will be made.” Several basic tasks were mandated to move the organization forward, out of its isolation from the mass of the working class, to be in a better position to play a decisive role in the rapidly unfolding and spreading labor upsurge. It was decided that the Party was to refocus its primary efforts on organizing the workplaces and unions, specifically in geographic areas where key industries were concentrated. Expanded work was directed in the left-led unions and labor movement generally. It called for greatly increased activity among the unemployed, for a complete overhaul of work to expand distribution of the Party press and therefore its message. It called for the Party to embark on a program to dramatically expand the ranks of Party leaders and cadre drawn primarily from the workshops and unions. Other work of the Party was not abandoned, but all of it was rethought and relaunched to support and complement the new emphasis. The results were immediate. New members began to trickle in, then pour in. Work in the unions exploded on all fronts, placing the Communist Party in the leadership of more labor struggles than it could have imagined just the previous year. Party morale zoomed as nearly everyone sensed that the decisions of the Extraordinary Conference had been correct. Can We Do Anything Today? Could any process such as that recounted here with the Extraordinary Conference be replicated today? So far as the status today of the left-wing organizations and networks, they apparently continue to slowly grow and develop, albeit without any central strategy or concentration of activity. With only a few exceptions the left organizations remain small and scattered although virtually all have grown significantly in the past decade. Much of the new membership arrives spontaneously or anonymously via the Internet. Members lapse or drop and there are few explanations for why they did this. Actual programmatic recruitment seems sparse and is sometimes completely neglected. Organizational functioning seems haphazard, and in some cases is conducted solely by Internet. In-person meetings and work still lag on account of the pandemic’s residual effects and likewise because of the widely scattered membership. Tremendous energy is expended on support for left Democrats running for office – or governing – in some of the organizations. The jury seems out on whether this work builds the organization of the Democratic Party or of the socialist organization offering the free assistance. Every left group or chapter announces its formation with a creative logo, a web site, and with an ample social media presence, just before deciding “what to do first?” Actual discussion of socialism or study of socialist history or philosophy seems to be underway here and there but is not promoted widely. Socialist oriented podcasts, videos, and on-line journals seem to be having no problem growing and expanding – and reaching a significant audience – but few put any emphasis on actually building the socialist movement in any concrete way. For the first time in many decades, it appears that the center of gravity for the left has migrated away from the college campuses and into the communities, although the colleges and universities continue to dominate the vast bulk of left leadership and writing. “Socialist” activism today is most certainly rooted and focused on activities mostly outside of the workplace, outside of the unions, with some noted exceptions. As was the situation facing the left organizations and the Communist Party of 1933 there were hopeful signs and good works being done, some progress, but not nearly enough of either. As for the workplace and trade union work of the left organizations today, there is only spotty and relatively recent work in evidence. All is positive, but as yet in too small a supply to be decisive or even measurable in many places. Anecdote might also lead us to conclude that the majority of workplace and trade union work underway by the left is spontaneous and not deliberately organized, a result of no more than the need of everyone post-school to go to work and somehow earn a living. The development and reinforcement of left forces within the unions is fragmentary at best, and as the last retirements of the 1970’s generation proceed many unions find themselves without any substantial left-wing membership or activism. There are widespread numbers of dedicated socialist trade unionists and hopeful organizers and salts at work, but again scattered with apparently little coordination, strategy, or common mission. Ignore Workers? Or Reach Out to the Working Class? Critics and opponents of the Open Letter and its methodology will likely point out that the degree of organizational unity and action that the Communist Party was able to muster was the result of a Leninist, meaning “democratic centralist” party structure and functioning. They might offer that to expect today’s left-wing groups to function with this degree of cohesion and discipline is unrealistic, even impossible. But this instantaneous rejection of a refocused course of action is defeatist in the extreme, perhaps unintentionally so. Trade unions are periodically able to adopt a unifying common mission, then apply resources and leadership effort towards that goal. The decision by the socialist organizations to refocus on workplace and trade union organizing does not require a restructuring of the organization along Leninist lines. Such a direction would be beneficial but is not required for the concentration on the working class to be initiated.The left organizations have for the most part avoided concentration on the workplace and the unions for decades, and their decisions to focus on the “community” aspects of work has proven to yield a poor return for the oceans of effort poured into it. As William Z. Foster proved with both the meat packing campaign and the great steel organizing drive – and later the steel strike – otherwise small and scattered left forces can literally move mountains when there is a clear, defined, and achievable goal with realistic time frames offered for the duration of the struggle. The bulk of Foster’s early work and accomplishments were not the result of the work of disciplined Leninist cadre but were instead the result of a relative handful of single-minded militants leading significant numbers of members in the unions – and relentlessly pushing on the union leaderships to carry out a popular course of action. Mass campaigns are feasible today that would sweep into action large numbers of militants and members with no required discipline other than common agreement. The existing left organizational leadership must be won over to this understanding, and to an admission that so long as the left organizations pursue a loose, unfocused, and scattered program of activity that the results will remain small. So long as the left organizations treat the workplace and unions as an afterthought, or as a sideline, the bottomless basket of left issues will forever take precedence over direct worker contact and organization. And unless the socialist movement is able somehow to root itself directly in working class struggles, history has shown repeatedly that it will ebb and flow and eventually dissipate as new issues du jour appear and disappear. The Left Wing Must Do the Work The legacy of the Extraordinary Conference and its Open Letter is sadly forgotten but should be revisited. Not only for the organizational lesson that it offers, but because it requires socialist leadership to accept responsibility for their work and performance. The resolve of the Communist Party leadership and membership that flowed forward from the Conference and its Open Letter set a tone and course for a focus on union organizing and contact with the working masses that contributed greatly to the 1930’s radicalization. The foundations of the CIO upsurge were laid in many quarters by the work of the trade union militants in or around the Communist Party, and by millions of ordinary workers swept up in the left-wing spirit of the times. Left organizations other than the Communist Party – small and not so small alike – for the most part all turned their focus towards working class organization and trade union struggles in that period. These factors all contributed to the largest socialist and trade union organizational growth in the past 100 years. Several of the significant left organizations and networks now approach their respective conventions in the year to come. Is such a refocus on the centrality of the class struggle and the working class possible, even in part? Can it be placed on the agenda? Will forces emerge to promote something resembling a concentration on the workplaces and the unions? Or will the situation persist where all issues are treated as equals, with little emphasis, and little hope of significant growth and revival of the labor movement? Will the leadership of the left organizations be measured by their performance so far as building the organization and its real reach, or will they be swept again into office based on a renewed approach to methods already proven to be failed? I encourage all of the left militants, trade unionists, and workers toughing it out in the shops trying to organize to familiarize themselves with the Open Letter. It is perhaps a modern-day guide for action today. Author-Chris Townsend was a member and staff member of the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) and the United Electrical Workers Union (UE) for a combined 38 years. He continues to work as a union organizer today. He may be reached at [email protected] This article was republished from Marxism-Leninism Today. Archives June 2023 6/29/2023 Ukraine Violated Peace Agreement Approved in Turkey, Putin Reveals By: Al Mayadeen EspañolRead NowRussian President Vladimir Putin revealed during an African leaders meeting in St. Petersburg that Russian forces had withdrawn from Kiev and other regions of Ukraine last year in compliance with a peace agreement reached in Turkey, as part of an African mediation mission to Russia. However, during the meeting with the members of the African delegation, who were entrusted with presenting an initiative to resolve the Ukrainian conflict, Putin informed them that Kiev had declined to sign the pact following the voluntary departure of Russian troops. The Russian head of state presented the document negotiated by both sides, entitled “The Treaty of Permanent Neutrality and Security Guarantees for Ukraine.” He explained that Moscow and Kiev initially accepted a draft agreement in the spring of 2022 in Istanbul, in which China, Russia, the United States, France and Turkey acted as guarantors. At the time, as British Prime Minister Boris Johnson made a visit to Ukraine, various media outlets, including those in Russia, swiftly linked his trip to Volodymyr Zelensky’s refusal to endorse the agreement. Media outlets such as Foreign Affairs attested to Johnson’s efforts to thwart the deal for two reasons he believed to be valid: First, it is not possible to negotiate with Putin, and second, the West is not prepared for an end to the war. According to Responsible Statecraft, Saturday’s release of this document casts doubt on Ukrainian narratives regarding Russia’s defeat in the Battle of Kiev in the spring of last year and its withdrawal from the surrounding area. In particular, it serves to underscore how Ukraine is being used as part of a calculated maneuver in the Western proxy war against Russia, further clarifying Ukraine’s sacrificial role. The food crisis not caused by Russia The Russian President also explained that the world food crisis was caused by the actions of Western countries, which started long before the armed conflict not by Russian military operations in Ukraine. Putin expressed his country’s readiness to establish a constructive dialogue with those who want peace, and praised the balanced approach of the African delegation’s mediators to the conflict. The African mission visiting Russia includes four presidents: South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa, Senegal’s Macky Sall, Zambia’s Hakende Hichilema, and the Comoros’ Ghazali Osmani, also the rotating chairman of the African Union. There are also representatives from Congo-Brazzaville, Uganda, and Egypt. (AlMayadeen) Translation: Orinoco Tribune AuthorThis article was republished from Orinoco Tribune. Archives June 2023 Imagine if you will, that we lived in a country in which TV and movie scripts were produced for merit and not edited and censored to ensure compliance with capitalist ideology. Imagine that in this fictitious USA, it were possible to make movies celebrating heroic leaders of the struggles for working people, Black people, and immigrants. Imagine that those films could be financed, promoted, and viewed as widely as the mindless tripe we are currently subjected to that encompasses all sorts of idiocy from vampire scripts, to “reality” TV, or films making heroes of CIA agents or as forces for good in an evil world. In such a world, a movie maker would go to unimaginable lengths to obtain the rights to Working Class Giant, the Life of William Z. Foster, written by his former aide, Arthur Zipser. This 215-page offering from International Publishers screams to be made into an epic work on the life of a man for whom the term giant is no exaggeration. Foster was born in 1881 in Taunton, Massachusetts but moved to a tough, ramshackle neighborhood in Philadelphia known as Skittereen when he was seven. His is truly a story of a man from humble beginnings achieving remarkable goals, all to further the interests of working men and women. He fought for racial equality. He opposed efforts to split up workers through ethnic division. He championed equal pay for women, international solidarity of workers and socialism. His accomplishments are far too long to list here but some of his roles included teacher, organizer, author, strike leader, reporter, editor, theoretician, US Presidential candidate, worker, diplomat, and husband and father! Foster was so feared by the capitalists that he was twice seized and kidnapped by them, in Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1919 and Denver, Colorado 1922 to keep him away from the striking steelworkers and railroad workers he was supporting. He was shot at, beaten, arrested numerous times, smeared, condemned from the floor of the House of Representatives. He served two prison terms and was indicted under the Smith Act. Foster joined the Communist Party in 1921 and was a tremendous asset in a time of factional struggles and attempts to destroy the party from within. The young party resisted the efforts of the most powerful government on earth to crush it. He served in leadership and ran for US President three times on the party ticket receiving 102,991 votes in 1932. He did all this and more, but most of all, he was revered by working people everywhere because he shared their pain and aspiration for a better life for themselves, their families, their neighbors. He was profoundly moved by their suffering describing the 1931 coal strike as, “one of the severest strikes I’ve ever went through. ………. it was heartbreaking to see starving miners being cut to pieces by the ruthless operators.” in 1941 Theodore Dreiser on Foster’s 60th birthday declared “To me he is a saint-my first and only contact with one……..a leader among leaders who has always kept faith with the working man.” Gus Hall wrote, ”He was the very best that the U.S. working class has produced.” Foster’s sixtieth birthday party at Madison Square Garden attracted 18,000 people. Paul Robeson sang! Despite being initially published in 1981, the now reprinted book is as timely as ever as the country begins to see an organizing and strike upsurge. Its historical accounts cannot be retold often enough. If you have not read it, do so now. If you have read it, relive the story of a titan. The latest edition includes a very fine introduction by a passionate disciple of Foster, Chris Townsend, former Legislative Director for the United Electrical Workers and former Organizing Director for the Amalgamated Transit Union. AuthorBob Bonner is former president of AFGE Local 2028 in Pittsburgh, PA where he represented US Veterans Administration workers. This article was republished from Marxism-Leninism Today Archives June 2023 6/29/2023 Millions of people in the US ration medicine as Big Pharma fights to keep prices high By: Natalia MarquesRead NowA new CDC study shows that 9 million people are trying to save money by rationing medication, as pharmaceutical giants rally against price checks A new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report published this month reveals that approximately 9.2 million people in the US try to save money by rationing their medication. Most adults between the ages of 18 and 64 take at least one prescription medication, but 8% of them—9.2 million people—ration medicine by skipping doses, taking less than instructed, or delaying a refill. Meanwhile, pharmaceutical giants like Merck are fighting tooth and nail against President Biden’s limited checks on astronomical medication prices. Giving the government power to negotiate medicine prices with companies is “tantamount to extortion,” Merck argues in a recent lawsuit. Based on data from 2021, the CDC found that the most marginalized of the working class are the ones who are most often forced to ration their medication. Almost a quarter of adults (23%) without insurance rationed their medication in order to save money, versus 7% of people with private insurance. 27 million people in the US have no health insurance at all. People with disabilities were three times more likely to ration medication than non-disabled people, as well as those with fair or poor health as compared to good health. Women were more likely to ration medicine than men. A report published in November of 2022 found that one in six people with diabetes rationed their insulin. The number was one in four for Black people with diabetes. A third of uninsured adults rationed. “The main takeaway is that 1.3 million people rationed insulin in the United States, one of the richest countries in the world,” Dr. Adam Gaffney, Harvard Medical School physician and lead author of the study, told CNN. “This is a lifesaving drug. Rationing insulin can have life-threatening consequences.” “There are stories of many folks in the states who are living with type one diabetes, for instance, who will try to stretch doses, try to make it to the next month and a lot of those folks don’t make it,” said Justin Mendoza, executive director of Universities Allied for Essential Medicines. “You can’t really survive without the proper dosage of insulin if you have Type 1 [diabetes].” As working people are risking their lives to save money on costly medications, pharmaceutical giant Merck is suing the US government over a law that would empower the state to negotiate prices with companies for a limited amount of branded medicine. This reform in the Inflation Reduction Act of last year “is tantamount to extortion” Merck argues. AbbVie’s CEO claimed that the IRA’s negotiations amount to “price controls” (not that there would be anything wrong with this, many of the world’s largest countries have some system of price controls of medications). Biogen is predicted to follow Merck with their own suit against the IRA. Their CEO also agreed that the IRA is “extortion” and called the law “draconian,” and would prevent them from funding medical research on rare diseases. But the battle for Medicare, the state-run health insurance program, to be able to negotiate medication, has been going on for a long time. “Medicare should have always had the ability to negotiate lower prices for its enrollees, because Medicare is the largest purchaser of prescription drugs in the US,” says Mendoza. In 2003, “when the law was passed to get [Medicare Part D] through, pharmaceutical companies lobbied and kicked up a couple of votes and got the restriction in place that barred Medicare from negotiating.” Merck made over USD 14 billion in profits last year, AbbVie generated almost USD 12 billion, and Biogen USD 3 billion (a 95% increase from 2021). The companies seem unwilling to dip into their billions in profits to save the lives of poor and working people and fund necessary research. “Pharmaceutical prices have been unchecked for far too long,” says Mendoza. “We’ve seen that consistently for more than a decade, that pharmaceutical companies, when they have a monopoly, will raise the price so they can show profits to their shareholders and keep their investors happy.” “This is just yet another tactic used by large pharmaceutical manufacturers to try to hold on to profits without innovating anything new for patients.” AuthorNatalia Marques This article was republished from Peoples Dispatch. Archives June 2023 De-dollarization is apparently here, “like it or not,” as a May 2023 video by the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a peace-oriented think tank based in Washington, D.C., states. Quincy is not alone in discussing de-dollarization: political economists Radhika Desai and Michael Hudson outlined its mechanics across four shows between February and April 2023 in their fortnightly YouTube program, “Geopolitical Economy Hour.” Economist Richard Wolff provided a nine-minute explanation on this topic on the Democracy at Work channel. On the other side, media outlets like Business Insider have assured readers that dollar dominance isn’t going anywhere. Journalist Ben Norton reported on a two-hour, bipartisan Congressional hearing that took place on June 7—“Dollar Dominance: Preserving the U.S. Dollar’s Status as the Global Reserve Currency”—about defending the U.S. currency from de-dollarization. During the hearing, Congress members expressed both optimism and anxiety about the future of the dollar’s supreme role. But what has prompted this debate? Until recently, the global economy accepted the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency and the currency of international transactions. The central banks of Europe and Asia had an insatiable appetite for dollar-denominated U.S. Treasury securities, which in turn bestowed on Washington the ability to spend money and finance its debt at will. Should any country step out of line politically or militarily, Washington could sanction it, excluding it from the rest of the world’s dollar-denominated system of global trade. But for how long? After a summit meeting in March between Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and China’s President Xi Jinping, Putin stated, “We are in favor of using the Chinese yuan for settlements between Russia and the countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.” Putting that statement in perspective, CNN’s Fareed Zakaria said, “The world’s second-largest economy and its largest energy exporter are together actively trying to dent the dollar’s dominance as the anchor of the international financial system.” Already, Zakaria noted, Russia and China are holding less of their central bank reserves in dollars and settling most of their trade in yuan, while other countries sanctioned by the United States are turning to “barter trade” to avoid dependence on the dollar. A new global monetary system, or at least one in which there is no near-universal reserve currency, would amount to a reshuffling of political, economic, and military power: a geopolitical reordering not seen since the end of the Cold War or even World War II. But as a look at its origins and evolution makes clear, the notion of a standard global system of exchange is relatively recent and no hard-and-fast rules dictate how one is to be organized. Let’s take a brief tour through the tumultuous monetary history of global trade and then consider the factors that could trigger another stage in its evolution. Imperial Commodity Money Before the dollarization of the world economy took place, the international system had a gold standard anchored by the naval supremacy of the British Empire. But a currency system backed by gold, a mined commodity, had an inherent flaw: deflation. As long as metal mining could keep up with the pace of economic growth, the gold standard could work. But, as Karl Polanyi noted in his 1944 book, The Great Transformation, “the amount of gold available may [only] be increased by a few percent over a year… not by as many dozen within a few weeks, as might be required to carry a sudden expansion of transactions. In the absence of token money, business would have to be either curtailed or carried on at very much lower prices, thus inducing a slump and creating unemployment.” This deflationary spiral, borne by everyone in the economy, was what former U.S. presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan described in his famous 1896 Democratic Party convention speech, in which he declared, “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” For the truly wealthy, of course, the gold standard was a good thing, since it protected their assets from inflation. The alternative to the “cross of gold” was for governments to ensure that sufficient currency circulated to keep business going. For this purpose, they could produce, instead of commodity money of gold or silver, token or “fiat” money: paper currency issued at will by the state treasury. The trouble with token money, however, was that it could not circulate on foreign soil. How, then, in a global economy, would it be possible to conduct foreign trade in commodity money and domestic business in token money? The Spanish and Portuguese empires had one solution to keep the flow of metals going: to commit genocide against the civilizations of the Americas, steal their gold and silver, and force the Indigenous peoples to work themselves to death in the mines. The Dutch and then British empires got their hands on the same gold using a number of mechanisms, including the monopolization of the slave trade through the Assiento of 1713 and the theft of Indigenous lands in the United States and Canada. Stolen silver was used to purchase valuable trade goods in China. Britain stole that silver back from China after the Opium Wars, which China had to pay immense indemnities (in silver) for losing. Once established as the global imperial manager, the British Empire insisted on the gold standard while putting India on a silver standard. In his 2022 PhD thesis, political economist Jayanth Jose Tharappel called this scheme “bimetallic apartheid”: Britain used the silver standard to acquire Indian commodities and the gold standard to trade with European countries. India was then used as a money pump for British control of the global economy, squeezed as needed: India ran a trade surplus with the rest of the world but was meanwhile in a trade deficit with Britain, which charged its colony “Home Charges” for the privilege of being looted. Britain also collected taxes and customs revenues in its colonies and semi-colonies, simply seizing commodity money and goods, which it resold at a profit, often to the point of famine and beyond—leading to tens of millions of deaths. The system of Council Bills was another clever scheme: paper money was sold by the British Crown to merchants for gold and silver. Those merchants used the Council Bills to purchase Indian goods for resale. The Indians who ended up with the Council Bills would cash them in and get rupees (their own tax revenues) back. The upshot of all this activity was that the Britain drained $45 trillion from India between 1765 and 1938, according to research by economist Utsa Patnaik. From Gold to Gold-Backed Currency to the Floating Dollar As the 19th century wore on, an indirect result of Britain’s highly profitable management of its colonies—and particularly its too-easy dumping of its exports into their markets—was that it fell behind in advanced manufacturing and technology to Germany and the United States: countries into which it had poured investment wealth drained from India and China. Germany’s superior industrial prowess and Russia’s departure from Britain’s side after the Bolshevik Revolution left the British facing a possible loss to Germany in World War I, despite Britain drawing more than 1 million people from the Indian subcontinent to serve (more than 2 million Indians would serve Britain in WWII) during the war. American financiers loaned Britain so much money that if it had lost WWI, U.S. banks would have realized an immense loss. When the war was over, to Britain’s surprise, the United States insisted on being paid back. Britain squeezed Germany for reparations to repay the U.S. loans, and the world financial system broke down into “competitive devaluations, tariff wars, and international autarchy,” as Michael Hudson relates in his 1972 book, Super imperialism, setting the stage for World War II. After that war, Washington insisted on an end to the sterling zone; the United States would no longer allow Britain to use India as its own private money pump. But John Maynard Keynes, who had written Indian Currency and Finance (1913), The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), and the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), believed he had found a new and better way to supply the commodity money needed for foreign trade and the token money required for domestic business, without crucifying anyone on a cross of gold. At the international economic conference in 1944 at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, Keynes proposed an international bank with a new reserve currency, the bancor, that would be used to settle trade imbalances between countries. If Mexico needed to sell oil and purchase automobiles from Germany, for instance, the two countries could carry out trade in bancors. If Mexico found itself owing more bancors than it held, or Germany had a growing surplus of them, an International Clearing Union would apply pressure to both sides: currency depreciation for debtors, but also currency appreciation and punitive interest payments for creditors. Meanwhile, the central banks of both debtor and creditor nations could follow Keynes’s domestic advice and use their powers of money creation to stimulate the domestic economy as needed, within the limits of domestically available resources and labor power. Keynes made his proposal, but the United States had a different plan. Instead of the bancor, the dollar, backed by gold held at Fort Knox, would be the new reserve currency and the medium of world trade. Having emerged from the war with its economy intact and most of the world’s gold, the United States led the Western war on communism in all its forms using weapons ranging from coups and assassinations to development aid and finance. On the economic side, U.S. tools included reconstruction lending to Europe, development loans to the Global South, and balance of payments loans to countries in trouble (the infamous International Monetary Fund (IMF) “rescue packages”). Unlike Keynes’s proposed International Clearing Union, the IMF imposed all the penalties on the debtors and gave all the rewards to the creditors. The dollar’s unique position gave the United States what a French minister of finance called an “exorbitant privilege.” While every other country needed to export something to obtain dollars to purchase imports, the United States could simply issue currency and proceed to go shopping for the world’s assets. Gold backing remained, but the cost of world domination became considerable even for Washington during the Vietnam War. Starting in 1965, France, followed by others, began to hold the United States at its word and exchanged U.S. dollars for U.S. gold, persisting until Washington canceled gold backing and the dollar began to float free in 1971. The Floating Dollar and the Petrodollar The cancellation of gold backing for the currency of international trade was possible because of the United States’ exceptional position in the world as the supreme military power: it possessed full spectrum dominance and had hundreds of military bases everywhere in the world. The U.S. was also a magnet for the world’s immigrants, a holder of the soft power of Hollywood and the American lifestyle, and the leader in technology, science, and manufacturing. The dollar also had a more tangible backing, even after the gold tether was broken. The most important commodity on the planet was petroleum, and the United States controlled the spigot through its special relationship with the oil superpower, Saudi Arabia; a meeting in 1945 between King Abdulaziz Al Saud and then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on an American cruiser, the USS Quincy, on Great Bitter Lake in Egypt sealed the deal. When the oil-producing countries formed an effective cartel, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and began raising the price of oil, the oil-deficient countries of the Global South suffered, while the oil exporters exchanged their resources for vast amounts of dollars (“petrodollars”). The United States forbade these dollar holders from acquiring strategic U.S. assets or industries but allowed them to plow their dollars back into the United States by purchasing U.S. weapons or U.S. Treasury securities: simply holding dollars in another form. Economists Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler called this the “weapondollar-petrodollar” nexus in their 2002 book, The Global Political Economy of Israel. As documented in Michael Hudson’s 1977 book, Global Fracture (a sequel to Super Imperialism), the OPEC countries hoped to use their dollars to industrialize and catch up with the West, but U.S. coups and counterrevolutions maintained the global fracture and pushed the global economy into the era of neoliberalism. The Saudi-U.S. relationship was the key to containing OPEC’s power as Saudi Arabia followed U.S. interests, increasing oil production at key moments to keep prices low. At least one author—James R. Norman, in his 2008 book, The Oil Card: Global Economic Warfare in the 21st Century—has argued that the relationship was key to other U.S. geopolitical priorities as well, including its effort to hasten the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1980s. A 1983 U.S. Treasury study calculated that, since each $1 drop in the per barrel oil price would reduce Russia’s hard currency revenues by up to $1 billion, a drop of $20 per barrel would put it in crisis, according to Peter Schweizer’s book, Victory. In 1985, Norman recounted in his book that Saudi Arabia “[opened] the floodgates, [slashed] its pricing, and [pumped] more oil into the market.” While other factors contributed to the collapse of the oil price as well, “Russian academic Yegor Gaidar, acting prime minister of Russia from 1991 to 1994 and a former minister of economy, has described [the drop in oil prices] as clearly the mortal blow that wrecked the teetering Soviet Union.” From Petrodollar to De-Dollarization When the USSR collapsed, the United States declared a new world order and launched a series of new wars, including against Iraq. The currency of the new world order was the petrodollar-weapondollar. An initial bombing and partial occupation of Iraq in 1990 was followed by more than a decade of applying a sadistic economic weapon to a much more devastating effect than it ever had on the USSR (or other targets like Cuba): comprehensive sanctions. Forget price manipulations; Iraq was not allowed to sell its oil at all, nor to purchase needed medicines or technology. Hundreds of thousands of children died as a result. Several authors, including India’s Research Unit for Political Economy in the 2003 book Behind the Invasion of Iraq and U.S. author William Clark in a 2005 book, Petrodollar Warfare, have argued that Saddam Hussein’s final overthrow was triggered by a threat to begin trading oil in euros instead of dollars. Iraq has been under U.S. occupation since. It seems, however, that the petro-weapondollar era is now coming to an end, and at a “‘stunning’ pace.” After the Putin-Xi summit in March 2023, CNN’s Fareed Zakaria worried publicly about the status of the dollar in the face of China’s and Russia’s efforts to de-dollarize. The dollar’s problems have only grown since. All of the pillars upholding the petrodollar-weapondollar are unstable: