|

8/15/2021 History as upheaval and progress enters stage with novelist Walter Scott. By: Jenny FerrellRead NowFray at Jeannie Mac Alpine’s (1836). Engraving by George Cruikshank of a scene from 'Rob Roy'. | Walter Scott Image Collection, Edinburgh University. CC BY 2.0 History is vanishing from school curricula; historical awareness is deliberately erased. Novels in historical settings portray characters as ahistorical, no different to 21st-century people, transporting a sense that people never develop, that society cannot and will not change. Such misrepresentation of the historical process fuels the sense that the world cannot be understood and any effort to change it for the better of humankind is ultimately futile. The history of literature shows that another kind of historical novel is possible, one that shows history as upheaval, people themselves as historical. Walter Scott and the historical novel Walter Scott, admired by his contemporaries Goethe, Pushkin, and Balzac, celebrated by Lukács as the founder of the historical novel, was born in Edinburgh 250 years ago on August 15, 1771. Born into the upper-middle class, his family preserved a sense of tradition of one of the great Scottish clans. This included folk heritage. Like Robert Burns, Scott grew up with the songs and legends of Scotland. He collected them and reflected them in his own work. This cultural awareness was accompanied by a deep sense of national identity.

Scott’s interest in Scottish border ballads led to his collection Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802-03), in which he endeavored to restore orally corrupted versions to their original wording. This publication made Scott known to a wide audience. His epic poem, The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805), was followed by further lyrical romances. During these years, Scott led a very active literary and social life. At the same time, he was deputy sheriff of Selkirkshire from 1799 and clerk of the court in Edinburgh from 1806, as well as part-owner of a printing press and later publishing house, which he saved from bankruptcy. Personal financial crises increasingly impacted on the course of his career and his writing became determined by the need to pay off debts. His estate in Abbotsford, furnished with many antiquarian objects, also consumed vast sums. In 1813, Scott rediscovered the unfinished manuscript of a novel he had begun in 1805, which he rapidly finished in the early summer of 1814. This novel Waverley, about the Jacobite uprising of 1745, was enthusiastically received. Like all of Scott’s novels written before 1827, Waverley was published anonymously. A born storyteller and master of dialogue in both Scots dialect and aristocratic etiquette, he was able to portray sensitively the whole range of Scottish society, from beggars and farm laborers to the bourgeoisie, the professions, and the landowning aristocracy. Scott’s sensitivity to ordinary people was a new orientation. He convincingly portrayed outlandish highlanders as well as the political and religious conflicts that shook Scotland in the 17th and 18th centuries. Scott’s masterpieces include Rob Roy (1817), The Heart of Midlothian (1818), and his most popular novel, Ivanhoe (1819). Unfortunately, the haste with which he wrote his later books affected Scott’s health as well as his writing. In 1827, his authorship of the Waverley novels became known. In 1831, his health deteriorated badly and he died on September 21, 1832. Scott’s times Scott lived and wrote in an era of enormous upheaval: Revolutions in France and North America, uprisings in Haiti and Ireland, the Napoleonic wars, the expansion of the British Empire, its domination of the seas, the slave trade, the uprooting of large sections of Britain’s peasantry through enclosure for the purpose of sheep farming, increasing capitalist “rationalization” of the countryside, large-scale highland clearances evicting highlanders from their land. The beginnings of the Industrial Revolution consolidated the power of the bourgeoisie, and the first political organizations of the working class emerged. Such density of dramatic events suddenly made the course of history, the progression from one society to another, directly tangible. History unfolded before everyone’s eyes and, it seemed, could be influenced. This is the shifting ground on which Scott’s historical novel is set. In addition, literary production in Scotland and Ireland flourished. Here, on the colonial edges, questions of history and cultural identity, colonialism, and anti-colonialism sharply crystallized. This begins in Ireland with Swift and his magnificent writings against British colonial power from the perspective of the Irish people as early as the 1720s. In Scott’s time, the Irish people speak in their idiom in Maria Edgeworth’s novels. While England in the 18th century is preparing for the Industrial Revolution, politically it is already a post-revolutionary country, following the English Bourgeois Revolution of 1649. The emergence of the historical novel As Georg Lukács argues convincingly in The Historical Novel, this genre emerges with Scott at this time. There had been novels with historical themes in the 17th and 18th centuries, however, their characters and plots were taken from the time of the authors, who did not yet grasp their own epoch as historical. Scott’s novels introduce a new sense of history to the English realist novel tradition. While Scott neither creates psychologically profound individuals nor reaches the level of the rising bourgeois novel, he vividly embodies for the first time historical-social types. His main characters’ conflicts give artistic expression to social crises. The task of the protagonists is to find neutral ground on which the opponents can coexist. The main characters are usually tied to both camps. Pointing out a middle path is typical of Scott’s novels; this is where his political conservatism expresses itself. For Scott, outstanding historical figures are representatives of a movement that encompasses large sections of the people. This passionate character unites various sides of this movement and embodies the aspirations of the people. Through Scott’s plot, readers understand how the crisis arose, how the division of the nation came about. It is against this background that the historical hero appears. The broad panorama of social struggles illuminates, as Lukács writes, how a particular time produces an heroic person, whose task it becomes to solve historically specific problems. These leaders, directly linked to the people, often overshadow the main characters. Historical authenticity is achieved through condensed dramatic events and the collision of opposites. By interweaving personal fates of people with historical upheavals, Scott’s narrative is never abstract. Ruptures run between generations, between friends and affect them deeply down into their personal lives. Scott’s great strength lies in the credible narration of human relationships in the historical age depicted. Ivanhoe With Ivanhoe, Scott reaches far back into history. The novel is set around 1194, when the Norman Richard the Lionheart—King of England, Duke of Normandy, and Count of Anjou—returns to England from his various adventures in the Crusades and from prisons in Austria and Germany. The Anglo-Saxon Ivanhoe, loyal knight in Richard’s army, also appears in England in disguise. The central historical conflict of the novel is between the Anglo-Saxons of England and the Norman conquerors. The people are largely Anglo-Saxon, the feudal upper-class Norman. Parts of the Anglo-Saxon nobility, deprived of political and material power, still retain some aristocratic privileges and form the ideological and political center of Anglo-Saxon national resistance to the Normans. Yet Scott shows how parts of the Anglo-Saxon nobility sink into apathy, while others await the opportunity to reach a compromise with the more moderate sections of the Norman nobility, which Richard the Lionheart represents. When Ivanhoe, the title character and also a supporter of this compromise, disappears from the novel’s plot for quite a time and is overshadowed by secondary characters, this formal structure illuminates the historical-political reference to an absent compromise. The characters who overshadow Ivanhoe include his father, the Anglo-Saxon nobleman Cedric, unflinchingly insisting on anti-Norman positions, who even disinherits Ivanhoe because of his allegiance to Richard’s army, as well as his serfs, Gurth and Wamba. Above all, however, this includes the leader of the armed resistance against Norman rule, the legendary Robin Hood. The true heroism with which the historical antagonisms are contested comes, with few exceptions, from “below.” The folk figures are depicted with great vitality and nuance, while the antagonists tend to be stereotypes with little development. But neither does Ivanhoe change. Isaac the Jew is also stereotyped, although the same cannot be said of his daughter Rebecca, who captures the reader’s heart. Letters to Scott complained that Ivanhoe does not marry Rebecca at the end, but the comparatively pale Anglo-Saxon Rowena. The author rejected such an ending as historically indefensible. Scott proves himself here once again to be a defender of the middle road. The future belongs to Ivanhoe, knight in the service of the moderate Norman Richard the Lionheart and son of the anti-Norman Anglo-Saxon Cedric. His marriage to Rowena points to this middle ground. Scott, in depicting historical conflict in the lives of the people, shows the energies ignited in the people by such crises. Consciously or unconsciously, as Georg Lukács notes, the experience of the French Revolution is in the background. Rob RoyPublished in 1817, this novel is, along with Ivanhoe, among Scott’s most famous. Written in 1816, practically 100 years after the events it describes—the first Jacobite uprising of 1715—the aim of the rebellions was to restore the Catholic Stuart dynasty and Scottish independence. At the same time, Scott sketches the Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots still living in clans, especially in the character of Rob Roy Mac Gregor. In this character, Scott creates a genuine folk hero with passionate humanity that lends heroic traits to this clan society. Rob Roy is nevertheless an individualized character, initially in disguise, a constant presence, and also a benchmark of heroism in this novel. Not only is he a center of passion in the novel, but his language is also deeply poetic. Thereby, the reader experiences the failure of the rising and the defeat of clan society as a tragic event. Typically for Scott, Rob Roy is not the novel’s main character. That is the narrator Frank Osbaldistone, son of a London merchant who refuses to join his father’s successful business and is sent to live with his uncle in Northumberland on the Scottish border. Instead of him, cousin Rashleigh enters the business. When the latter steals money and disappears with it to Scotland, Frank follows him and so meets Mac Gregor. This English narrator takes the neutral place, the common ground; Osbaldistone’s family lives on the Scottish border. At the end of the plot, he marries his Catholic cousin, Diana Vernon, who is closely associated with the Jacobins, thereby achieving a union between Presbyterians and Catholics envisaged by Scott. Vernon is a confident woman as is the indomitable Helen Mac Gregor. Both are highly intelligent people who are in complete command of their scenes. It is also important that Scott writes his extensive dialogue scenes in Scots dialect. This establishes a bond between characters and Scottish readers. Before him, Robert Burns had also written in the vernacular. To this day, this dialect establishes identification with ordinary Scots, as underlined by the two Scottish Man Booker prize winners, James Kelman and Douglas Stuart. Scott even ventures into Gaelic, translating these short expressions for the reader. Scott’s numerous annotations are culturally and historically enlightening. The Heart of Midlothian The novel following Rob Roy, The Heart of Midlothian, is set over 20 years later, in 1736-37. Midlothian is an historic county with Edinburgh as its capital; the Heart of Midlothian, however, is its prison. The novel opens with the Porteous riots. Porteous, Captain of the City Watch, ordered his men to bloodily suppress a riot during a public execution in the Grassmarket in Edinburgh in April 1736. He was lynched by the angry crowd for killing innocent civilians. As Arnold Kettle has noted, Scott unfolds a large social spectrum here, ranging from the urban underworld to the queen. At the center is Jeanie Deans, from a rural, puritan background who speaks in Lowland Scots. This young peasant woman is perhaps Scott’s greatest female character. Her unmarried sister Effie is accused of infanticide. Merely keeping a pregnancy secret was punishable by death under Scottish law at the time. Forced to conceal the birth to protect her father, Effie insists that she has not harmed the newborn. Despite great empathy for her sister’s fate, Jeanie’s puritan conscience forbids her to commit perjury that could save her sister. This is simply historically true and not modernized. Effie is sentenced to death, and the penniless Jeanie sets off for London to seek a pardon from the Queen. The trial is the central event, revealing clashing values and worlds, the conflict between David Dean’s old rural world and the world of the modern money-centered city. Jeanie’s struggle to save her sister reveals her deep humanity and courage. It shows that in crisis situations heroism can burst forth in ordinary people that is not visible in everyday life and of which people themselves are often not even aware. She proves what strength and heroism there is in the people when the situation calls for it, as it happens time and again in history. Scott brings history to life with such a portrayal of human resilience in a specific historical situation. Scott’s hallmark is depicting personal experience as part of history. Readers encounter outraged people in the Porteous Riots. Scott conveys the genuine conflict between the people and the guards, as well as the bitter hostility of the Scots towards the English state. The events clearly involve more than seduction and rescue. The second half of the novel is less successful, as Scott depicts the world not from the peasants’ point of view, but from that of the romanticized landowner, precluding realism. Parallel to the central conflict between city and country runs that between Scotland and England. Scott’s Edinburgh is not a random setting, but a Scottish city in a concrete historical situation. Scott’s characters are never outside their time. He reflects the complex relationship between personal and social forces in a person’s life. With his portrayal of historically specific circumstances and the vitality of his ordinary people, Scott prepares the ground for Dickens. Dickens, who came from the impoverished petty bourgeoisie, would little later make the ordinary people of London the heroes and heroines of his novels. AuthorDr. Jenny Farrell was born in Berlin. She has lived in Ireland since 1985, working as a lecturer in Galway Mayo Institute of Technology. Her main fields of interest are Irish and English poetry and the work of William Shakespeare. She writes for Culture Matters and for Socialist Voice, the newspaper of the Communist party of Ireland. This article was produced by People's World. Archives August 2021

0 Comments

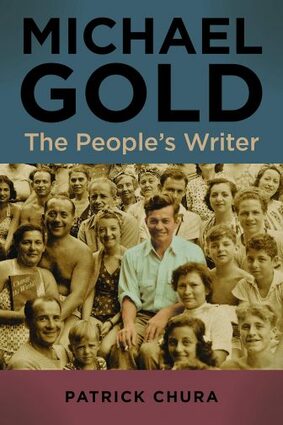

In the pantheon of 1930s revolutionary writers, Michael Gold has too long faltered on the historic periphery. A close associate of Hemingway, Reed, O’Neill, Hughes, St. Vincent Millay, Claude McKay, John Dos Passos, Dorothy Parker, Richard Wright, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, and James T. Farrell, Gold was not only overshadowed by the celebrity of others but blighted by decades of enduring discord from within and rabid anti-communism from without. And while his novel Jews Without Money (1932) was a bestseller, catapulting him to grand renown in his time, Gold’s own story has been painfully disappeared. Writers on the political left, in any case, have always looked to the breadth of Mike Gold’s mission: fiction writer, poet, playwright, prolific journalist and Daily Worker columnist, editor of New Masses and multiple other journals, he was also a champion cultural organizer and inspiring public speaker. Odd, that with so much literary adoration about him, with equal amounts of derision from other quarters, Gold’s biography would arrive at this late juncture. But given the depth of quality in Patrick Chura’s Michael Gold: The People’s Writer, the long, ridiculous wait was worth every decade. Chura, an English professor at the University of Akron, tore into the definitive research to tell the story, enliven the realities, and reveal the hidden. The biography, written not in the language of the academic but more in narrative fashion, glows with the evidence of investigative details. Chura shows an ability to absorb streams of reportage, unpublished poetry, early pencil visions of fiction, memoir notes, letters, seemingly lost first drafts as well as overlooked and forgotten works of a certain stature. It’s all here. As biographers are wont to do, Chura exposes the reader to the days of his subject, offering not only facts and analysis, but the ability to see these through Gold’s eyes — to feel the sweat and survive the strain of his often conflicted life. As told by Chura, Gold’s early life of poverty was centered around his family home, a crowded, nearly airless flat infested with lice and crushing dysphoria. Born Itzok Granich in 1894, Gold faced long hours of childhood labor when his ailing, bed-ridden father lost his struggling business, and the family became destitute. An excerpt of one of his earliest writings stated, “The streets of the East Side were dark with grey; wet gloom; the boats of the harbor cried constantly, like great bewildered gulls, like deep booming voices of calamity.” Much later, Gold would write of his formative years: “It was in a tenement that I first heard the sad music of humanity rise to the stars. The sky above the airshafts was all my sky; and the voices of the tenement neighbors in the airshaft were the voices of all my world. There, in my suffering youth, I feverishly sought God and found Man.” Chura may not be a New Yorker, but his book is a true snapshot of the city’s streets and shadows over the lengthy period bridging the early 20th century and Gold’s later years but in particular his 1920s–40s period of greatest activity. The reader is walked through 102 West 14th Street, then headquarters of the John Reed Club, and the offices of the Communist Party at 35 East 12th Street. It’s no small irony that rent for a single bedroom apartment in either now tops $5,000 per month, and apartment sales in the latter recently averaged more than $4 million. Chura also brings alive Gold’s radicalization as a teen, his early publication in the Masses, grave financial and emotional struggles while briefly at Yale, his journalist roots, youthful membership in the Provincetown Players, relationship with Dorothy Day, unfailing dedication to the Communist Party, and founding of the New Playwrights. But Gold’s “creative writing” was never confined to poetry, fiction, or drama. In his 1921 article “Towards Proletarian Art,” Gold eloquently warned that “a mighty national art cannot arise save out of the soil of the masses.” And of the Sacco and Vanzetti executions in 1927 Boston, he presciently reported, “It is August 14th, eight days before the new devil’s hour. . . . I am writing this in the war zone, in the psychopathic respectable city that is crucifying two immigrant workers . . . respectable Boston is possessed with the lust to kill . . . the subconscious superstition that the death of Sacco and Vanzetti can restore their dying culture and industry. At last, they have a scapegoat. . . . They are insane with fear and hatred of the new America.” This packed biography also reveals the protagonist’s battles with major depression and his lesser-known literature, including previously lost or forgotten verse and his 1929 collection 120 Million (after Vladimir Mayakovsky’s 150,000,000), long out of print. Gold’s numerous speaking engagements are cited, including some specific moments experienced at lecterns here and abroad. Such details feed into international travel, not the least of which was to Kharkov in the Soviet Union for the International Union of Revolutionary Writers conference and Paris for the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture. Interactions with European notables including Andre Gide, E. M. Forster, Vsevolod Meyerhold, and Vladimir Mayakovsky, poet laureate of the Soviet Union, are also highlighted. And while it’s clear that the author remains a proponent of Mike Gold, the many conflicts surrounding the man are here examined with jarring clarity. Though deeply committed to both the Communist Party USA and the wider Communist International, Gold’s rebellious, unbridled nature never allowed for the discipline exhibited by other party officials. The missed meetings and avoided functionary duties soon clarified that Gold’s decades as a revolutionist began in the company of anarchists. Ironically, his fights against party bureaucracy were eclipsed by the attacks he launched on progressive and liberal writers who’d apparently strayed from the mission. This combination — and a constant rain of blows from the right — established an array of opponents that stretched over a lifetime. Following early battles with Masses’ editor Max Eastman, his association with Claude McKay, too, became embittered (though he described McKay’s sonnets as “crystal songs”). Gold’s editorials railed against Gertrude Stein and sought to shred Thornton Wilder, but a particular hellishness was saved for former friends, most blatantly Ernest Hemingway. After publication of For Whom the Bell Tolls, Gold’s review called the book “a minor story” despite its “narrative genius,” as it was “so painfully fair to fascists.” The heroic figure of Robert Jordan, according to Gold, was ignorant of the class conflict in Franco’s Spain, which Gold saw as central to the story. Famously, Hemingway left a message at the New Masses office directing the critic to “go fuck himself.” In his book, The Hollow Men, an overview of writers he saw as having turned their backs on the revolution, particularly those originating from wealthier backgrounds (yes, he wrote of “Ernest Slummingway”), Gold’s opinions were unfettered, often bloodthirsty in the pursuit of forging an all-important literary force toward an egalitarian society and in opposition of fascism. Following word of the 1938 Moscow purges and, most painfully, the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact a year later, Gold was in the grip of conflict over what we later came to see as Stalin’s despotism. Yet, following his own advice to young writers, Gold would “write, persist, struggle,” toeing the party line through his doubt. During the worst of the Second World War, he became a constant source for the fight against fascism, and though a target of the Dies-led House Committee on Un-American Activities and constantly profiled by the FBI, Gold maintained a busy literary schedule in writing and editing. This sense of mission was maintained through his last, despairing years. While Gold was never to complete the second novel he’d long planned, his “Change the World” column was maintained through 1966, and the artful quality of his work remained glaringly so. He died in May 1967 after more than a half-century of embodying the cultural worker. Michael Gold, always one to analyze Marxian, seeking the wider, greater reality, wrote near the end of his life of the blacklist and McCarthy terrors, citing on manifold levels: “The lined faces which had seen the trouble and white hair as the result of sleepless nights. . . . We had lost all our youth.” Published in People’s World, May 18, 2021. Image: Mike Gold, Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 3.0). AuthorJohn Pietaro is a cultural worker and labor organizer from New York. He is a contributing writer to the People's World, Political Affairs, Z Magazine, Portside and other progressive publications. As a performer, John has shared the stage with artists such as Pete Seeger, Alan Ginsberg, Amiri Baraka, David Rovics, Fred Ho, Bev Grant, Anne Feeney and Ray Korona. His website is www.flamesofdiscontent.org. This article was published from CPUSA. Archives May 2021 |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed