|

5/21/2024 Book Review: Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism. By: Edward Liger SmithRead NowWhile neoliberalism is the economic and political ideology that dominates most of the Western world today, it is an ideology that is unknown to most American citizens. The purveyors of neoliberal ideology present themselves as objective and as being above ideology, which serves as a method of concealing the real underlying principles of neoliberalism, which are actually wildly unpopular with regular people. In this book journalist George Monbiot and filmmaker Peter Hutchison attempt to reveal these hidden principles of neoliberalism so that the ideology can be better understood and combatted. And while they do a good job revealing what makes neoliberal capitalism such a predatory, exploitative, unequal, imperialistic, and ecologically disastrous system, they also fall into the left-anticommunism that plagues so much of the Western left, which was critiqued brilliantly by Michael Parenti in his 1997 classic Blackshirts and Reds. The most valuable contribution of this book is that it traces the ideological history of neoliberalism through different thinkers such as Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig Von Mises, and Milton Friedman, up until today where neoliberals themselves now reject the word neoliberalism because of how unpopular it has become. Instead, neoliberals prefer to posture as being above ideology, and to portray the principles of neoliberalism as being natural and eternal. The authors show how the rise of politicians like Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Agusto Pinochet represent a transition away from Keynsianism and toward neoliberalism, or an unregulated, monopolistic, financialized, version of capitalism, justified by the idea that if we allow the rich to concentrate as much wealth and power into their hands as possible, then somehow this wealth will eventually “trickle down” to the rest of us at the bottom. Since the rise of Reagan and Thatcher inequality has skyrocketed, ecological degradation has accelerated, countless wars have been fought on behalf of corporate plunder, rents and debts are through the roof, and wealth has been concentrated at the top at unprecedented rates. The book also makes a pertinent and valuable analysis of the rise of right wing populist demagogues like the business tycoon Donald Trump in the US, the Musolini praising Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, and the far right Hindutva associated leader of India Narenda Modi. Monbiot and Hutchison avoid falling into what some have called “Trump derangement syndrome” by making a sober and realistic analysis of Trump’s rise to power, arguing convincingly that deteriorating economic conditions make people more susceptible to right wing demagogues who claim to be fighting the establishment while doing its bidding in reality. They point out that it was Bill Clinton, the husband of Hillary Clinton who Trump ran against in 2016, that allowed many good manufacturing jobs in middle America to be outsourced to the Global South with the passing of the free trade agreement NAFTA. Free trade is a core principle of neoliberal ideology, and thus the authors show how it is neoliberalism that set the stage for the populist right wing movement, masterminded by the likes of Steve Bannon, and brought to fruition by his preferred candidate Donald Trump. I also found the author’s analysis of mental health under neoliberalism to be pertinent, as too often we overlook the atomization of humanity and the lack of social connection that permeates throughout the neoliberal system. Obviously these factors play a role in the unprecedented rates of depression, opioid addiction, and mass shootings that now exist across the US. Too often the issue of social isolation in society is overlooked as politicians push half-baked cure-all solutions to these problems that won’t upset their corporate donors. For example the Democrats pushing for gun control, and gun control alone, everytime a new shooting takes place, while generally having very little to say about social isolation and the deterioration of community. It is important to understand that these social issues are complex and are rooted in the social system, and therefore, require systemic and complex solutions. The authors do a fantastic job of making this case in their systematic critique of neoliberalism. Neoliberals tell us that the current state of society is the way things have to be, that this is the natural order of life which must be maintained forever because there are simply no alternatives. And it is this assumption that Monbiot and Hutchison look to challenge in their book. However, by also claiming that communism is a “failed ideology” {1}full stop, with absolutely no explanation or analysis of why it has “failed”, they too are unwittingly propagating the idea that there is no alternative to capitalism. In the words of Michael Parenti, “to claim that Communism can never work is to ignore that fact that it has for millions of people around the world.” Today China is leading the charge against neoliberalism and in doing so have accomplished the incredible feat of bringing 800 million people out of poverty. {2} A fact that the authors of this book don’t even attempt to grapple with, instead falling back on the lame cold war talking point that communism has simply failed. I would encourage these two authors to read economist Michael Hudson’s fantastic article “America’s Neoliberal Financialization Policy vs.China’s Industrial Socialism”{3} which lays out in great detail the systemic differences between American neoliberalism and Chinese socialism. Although, if a positive word was spoken about Chinese socialism in this book it might not have gotten published by Penguin publishing house. Thus, the decision to badmouth socialism while completely ignoring all of its successes may have been more of a financial decision than a scholarly one. Existing socialist countries are only mentioned a few times in this book and always disparagingly. In Blackshirts and Reds Michael Parenti says “For decades, many left leaning writers and speakers in the United States have felt obliged to establish their credibility by indulging in anti communist and anti-Soviet genuflection, seemingly unable to give a talk or write an article or book review on whatever political subject without injecting some anti-red sideswipe. The intent was, and still is, to distance themselves from the Marxist Leninist Left.” {4} The authors of Invisible Doctrine: The secret history of neoliberalism repeatedly engage in this time honored tradition of bashing socialist countries in order to distance themselves from the communist left, and to fit their message within what is allowed by the established political orthodoxy. It’s amazing how the authors can be aware of the fact that our society is dominated by corporations, bankers, and shareholders, who spend billions of dollars trying to manipulate the public’s understanding of political economy, yet they seem to believe everything that these entities are telling us about communism. As a result the author's analyses of communism sound no different than what you would see in old school cold war propaganda, or a corporate owned news outlet like Fox. Parenti’s text goes on to say that “sorely lacking within the US (or in this case the British) Left is any rational evaluation of the Soviet Union.” {5} Likewise, sorely lacking from the Invisible Doctrine: The secret history of Neoliberalism, is any kind of rational evaluation of China, Cuba, Vietnam, or even non-socialist nations like Iran, who are attempting to construct an alternative economic system to Western neoliberalism. Which you’d think would be important in a text about neoliberalism. The authors choose to totally ignore the emerging multipolar world which is challenging the existing Western power structure and trying to bring about a world where the neoliberal US is no longer the unipolar global hegemon. Even the notedly anti-communist academic Noam Chomsky made a better analysis of China and the multipolar world in his recent book The Withdrawal which was a joint effort with Communist academic Vijay Prashad. {6} Instead of socialist nations like China, these authors choose to champion the region of Rojava as an existing example of a possible alternative to neoliberalism. Rojava is a semi-autonomous region in Syria which is governed by a self described socialist party with many different branches known as the PKK or the Kurdistan Workers Party. During the Syrian Civil War the PKK sided with the US and CIA backed Free Syrian Army which allied itself with Jihadist extremist groups like ISIS and Al-Nusra in their effort to overthrow the sovereign Government of Bashar Al-Assad. It was in the chaos of this horrific civil war that the Syrian Kurds were able to establish a semi-autonomous zone in so-called Rojava for the first time. Rojava and the PKK have been criticized, especially by the Marxist Leninist left, for acting as proxies of Western imperialism, and for enforcing ethno-nationalist policies that have reportedly led many Syrian Christians to flee Rojava. [7] The authors champion Rojava because of its efforts to implement Democratic reforms, socially progressive policies distinct from the rest of Syria, and to establish worker cooperatives. But there are many reasons to question whether Rojava should be upheld as a viable alternative to Western neoliberalism, especially when Rojava and the Kurds were recently used as pawns in a regime change effort led by Western neoliberals, intended to overthrow a sovereign state by putting arms in the hands of some of the worst extremist groups in the region. The US currently maintains seven military bases in so-called Rojava which further brings into question whether or not this region is truly a new kind of popular democracy distinct from Western neoliberalism. It is highly possible that Rojava is being allowed by Western neoliberals to experiment with some new forms of Governance so long as they continue to act as a proxy of Western power in the Middle East. {8} Similarly to Rojava, the state of Israel has adopted a progressive veneer in the past, claiming to be champions for women's rights and for the labor movement, or even claiming to have a socialist economic system due to the prevalence of worker co-ops. However, nobody in their right mind would argue that Israel is a country that anyone should attempt to emulate. As they have of course been charged with maintaining a system of apartheid that systematically discriminates against Palestinian Arabs, who have been ethnically cleansed by the US and British backed State of Israel for over 70 years. Palestinian living standards have reached disastrously low levels, and over 70% of Palestinian people are now living in refugee status, proving that it is impossible to build an equitable and democratic state so long as you allow yourself to be a pawn of western imperialism. We should be wary of any US backed countries that claim to be heroes for women's rights and Democracy. Comically, Parenti’s Blackshirts and Reds singles out two left anti-communist intellectuals for specific criticism, those being the anarchist environmentalist Murray Bookchin, and the self described socialist novelist George Orwell. Murray Bookchin once mocked Parenti for trying to make a balanced analysis of the Soviet Union by derriding him for caring so much about “the poor little children who got fed under communism” (his words). Ironically, it is Bookchin’s vision of a future society that Monbiot and Hutchison champion as the most viable alternative to neoliberalism. Despite the fact that no such society has ever been created and sustained in practice, unless you accept their fallacious argument about Rojava. This is not the case with Marxist-Leninist socialism, which has seen a great deal of success in practice, and has already elevated living standards for billions of people. The other ideologue who Parenti criticizes, George Orwell, used his voice to vehemently denounce and criticize the Soviet Union at a time when they were locked in a mortal struggle with Hitler and the Nazis. Ironically, George Monbiot won the Orwell award for journalism in 2022 and has since given lectures for the George Orwell Foundation {9} carrying on Orwell’s legacy of criticizing capitalism, while bashing and deriding those around the world who are doing the most to construct an alternative to it. While this book grasps the evils and contradictions of neoliberalism quite well, it fails to understand the geopolitical situation today in which a new multi-polar order is arising against US dominated neoliberal hegemony. The US is desperate for regime change in countries like China, Russia, Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, etc. because they continue to build stronger economic ties with one another, while preventing western neoliberals from plundering their resources and manipulating their Government policy. Confusingly, the authors at one point lump Russian President Vladimir Putin together with neoliberal demagogues around the world such as Bibi Netanyahu in Israel, Donald Trump in the US, and Narenda Modi in India. And while Russia did fall in line with the Neoliberal world order during the 1990s with the collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent plundering of the Russian economy by Western capital, under Putin they have largely reversed course, building stronger trade ties with China, nationalizing sections of the energy industry, cracking down on certain oligarchs and Russian firms, and investing more resources in infrastructure development. It is for these reasons that the US desperately seeks regime change in Russia today, dumping billions of dollars into a Ukrainian Proxy war against Russia, and terroristically blowing up the Nord stream Pipeline to sever Russian economic relations with Europe. The Russia of today, with Putin at the helm, is far from fitting in with neoliberal puppets of the West like Netanyahu in Israel or Zelensky in Ukraine. This is why Putin receives only vitriol from the US Government, while the other two receive a seemingly endless supply of money and guns. The authors also make the claim in this book that China’s production quotas under Mao Zedong had no social utility whatsoever, which simply shows a complete lack of understanding of Chinese history and socialist economic planning. Prior to the era of Mao, China was a feudal agrarian country with very little industry to speak of. The country was dominated by feudal landlords who ruled over vast swaths of land worked by impoverished peasants. In order for China to become a modern society Mao needed to industrialize the nation and teach these peasants to engage in modern economic practices such as steel working. This is why the now infamous backyard furnaces came about, as Chinese peasants had to be given tools by the state in order to teach themselves how to do modern industrial production. And while these policies were far from perfect, the first years of Mao’s rule in China were the fastest increase in human life expectancy that has ever been seen in human history. China transformed in a matter of decades from a backwards feudal agrarian dictatorship, into a modern economy where social metrics like literacy, housing, and access to healthcare, have been massively expanded. To say that the production quotas under Mao had no social utility, and to compare them to production as it now exists in the neoliberal United States, is a statement that can only be described as absurd and ignorant. The authors do choose to acknowledge the power of central economic planning and how it can be used to direct production towards social ends. However, instead of analyzing how the USSR and China used economic planning to transform themselves from being semi-feudal agrarian countries into industrialized global superpowers in a matter of decades, the authors instead choose to praise Franklin Delano Roosevelt for the way that he was able to direct all production towards military equipment during the Second World War. And to be fair, this is not a bad example. It does show that the US can, and has historically, used central economic planning to direct production toward social ends. However, to use this as an example while dismissing China’s use of central economic planning as a failure is completely ludicrous. An area of agreement I have with the authors is that the left of today needs to offer people a new narrative as to how our system can be radically changed. We at the Midwestern Marx Institute for Marxist Theory and Political Analysis have been attempting to do just that, by fleshing out a theory of American Marxism, or what we call the American Trajectory. We believe that America has already gone through three periods of revolutionary change, those being the 1776 revolution against british colonialism, the Civil War of the 1860s which abolished slavery and made capitalism the dominant mode of production in the American South, and the civil rights movement which did away with apartheid putting black and white workers on a more equal playing field, and allowing them to organize together against the ruling class as one. As Americans we need to understand that our history is one of colonial plunder and corporate power, but it is also a history of resistance to that power. Heroes like WEB Dubois and Martin Luther King helped to fight for historic advances that brought us to the situation we are in today free of slavery and apartheid. The struggles of the past have moved our society forward and set the stage for what must come next… American Socialism. The abolition of the neoliberal capitalist system and the transition into a truly democratic system where production is directed towards social ends, rather than the production of surplus value alone. This is the American Trajectory and this is the “New Story” that I believe we need to start selling the American Public on. Marxism is not a failed ideology. It is a science that must be applied uniquely to each country so that we might understand our current situation and how to change it through class struggle. Once we learn to apply Marxism to our own conditions and use it to understand our country’s history, we can start to understand how we got to the current situation, and how we can best move forward with changing it. There are many analyses in this book that are passed off as unique, but were already made by Karl Marx more than a century ago. Such as the idea that the ruling economic class of society will try to portray its own narrow interests as being in the interest of the whole of society, including the workers they exploit. This was something that Marx and Engels realized as early as 1840 in his text The German Ideology. The authors reformulate Marx and Engels’s analysis in different words without crediting or citing them, before turning around and claiming that Marxist ideology has failed. Such instances are common among Western Leftists who tend to throw endless shade at the work of Marx while copying some of his most important analyses of capitalism without credit. Despite falling into left-anticommunism throughout, the authors of Invisible Doctrine: the secret history of neoliberalism, provide a solid and pertinent critique of capitalism and the current neoliberal social system. Because of this book, many people will come to understand how the social problems we face today are rooted in capitalism, and the neoliberal political ideology that stems from it, and serves to justify its continued existence. The book proves without a shadow of a doubt that for the vast majority of people living under neoliberalism the system has failed. However, by arguing that capitalism's antithesis, socialism, has also failed, the authors further confuse the masses and push them to seek solutions in the anarchist school of thought which has yet to produce a successful revolution, or build a social system separate from western capitalism and imperialism. By arguing that keynesianism, neoliberalism, and socialism have all failed the authors extinguish some of the hope that the masses might place in the rise of socialism and the multipolar world. This might be acceptable if the authors made a sober analysis of rising socialist powers like China and Cuba, or their non-socialist allies like Russia and Iran, in order to argue that their rise will not be enough to destroy neoliberalism, and there is still much work to be done by workers here in the imperial core. Which is an argument that I would agree with. However, the authors instead fall back on cold war style state department talking points to dismiss these rising socialist and socialist adjacent powers without offering a shred of real analysis. And thus the book gives a solid analysis of neoliberalism, but confuses the current state of geopolitics by neglecting to analyze the massive and growing resistance to neoliberalism that is taking place in the East and the Global South. Read this book if you want to gain a better grasp on modern neoliberalism, and especially its ideological roots which can be traced back to the beginning of the last century. However, also make sure to pick up Vijay Prashad and Noam Chomsky’s The Withdrawal for a more all encompassing and accurate analysis of the current geopolitical situation. Also don’t be afraid to pick up some Marx and Lenin. I promise there is more to learn from them than what much of the Western left would lead you to believe. Citations

Author Edward Liger Smith is an American Political Scientist and specialist in anti-imperialist and socialist projects, especially Venezuela and China. He also has research interests in the role southern slavery played in the development of American and European capitalism. He is a wrestling coach at Loras College. Archives May 2024

5 Comments

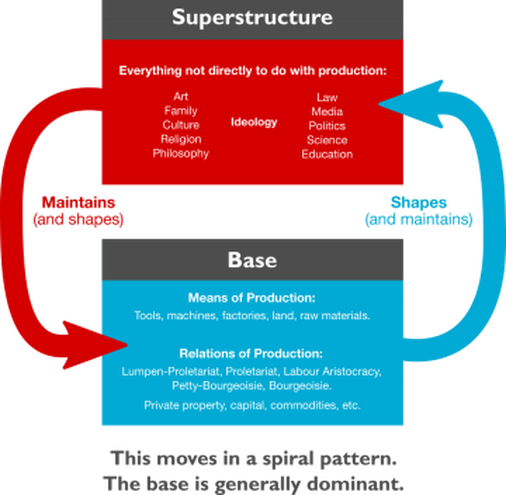

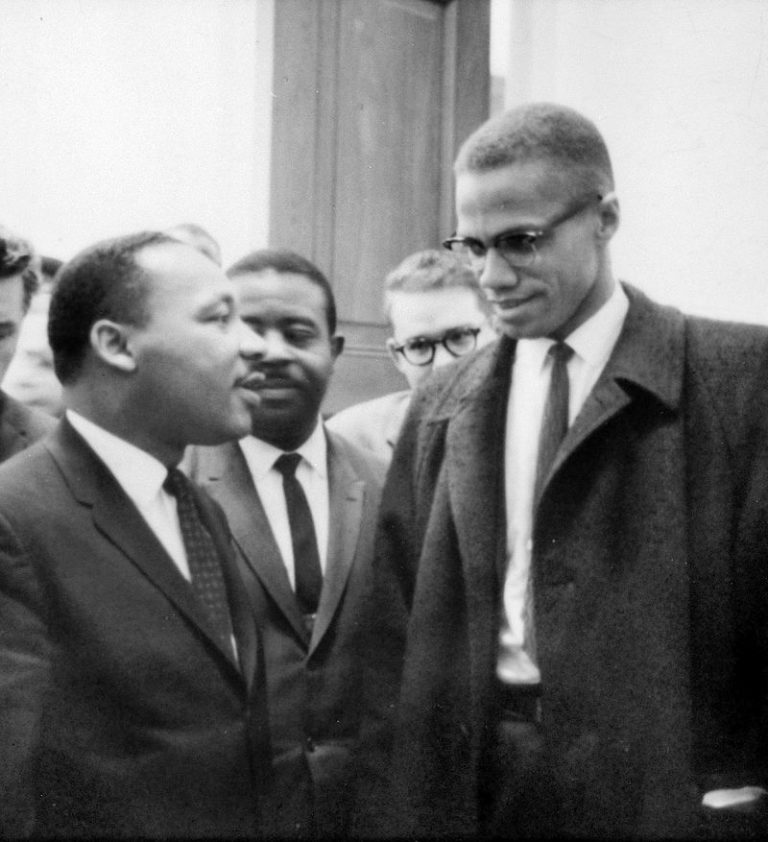

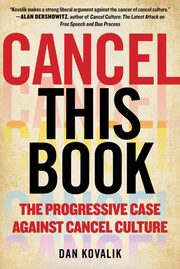

4/29/2024 Review: Angela Harris – Strike Story: A Dramatic Retelling of the Little Falls Textile Strike of 1912 (2013). By: J.N. CheneyRead NowTo highlight the more obscure pieces of labor and socialist history is a noble feat. Though the academic realm is vital for such an act, artistry is of similar significance. Not every piece can be a grandiose display of dense intellectualism full of jargon with highly specific details, sometimes a more colloquial, entertaining piece is necessary in spotlighting a particular history. The play Strike Story: A Dramatic Retelling of the Little Falls Textile Strike of 1912 by Angela Harris is one of those pieces designed to fill the gap between dense academia and the simplification of say, a blog post. Now for clarification’s sake, this is purely a review of the written form of the play. I was fortunate enough to be kindly gifted a copy of the play by Angela Harris herself, however I have not yet had the opportunity to view the actual live production in person or in video form. As the title implies, Strike Story is a dramatization of the events that unfolded within the Little Falls Textile Strike that went on from early October of 1912 to early January of 1913. This strike was primarily made of working immigrant women employed by two different textile mills in the city of Little Falls, New York. A three act play, the production is structured with a chorus outlining the happenings of the strike as fictionalized versions of the strike’s historical actors provide further details from their perspectives. Numerous important strike figures are represented in this piece, including Matilda Rabinowitz, an organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, George Lunn, the first and only socialist mayor of the city of Schenectady, New York, and Helen Schloss, a socialist and public travelling public health nurse. Of all of these significant figures, none of the “characters” in this strike are of more importance than one known only as the “Woman Striker,” a representative of who this strike is really all about; the workers fighting for a fair wage. It is of our own importance though to understand what exactly brought about this fight in the first place. Act one of the play is the only one broken up into two scenes. The first two scenes are designed to provide a brief explanation as to why exactly the strike came about in the first place. In act one, scene one, various characters are introduced using the chorus as a framing device. The chorus gives the context of the introduction of a law in New York limiting the amount of time women and children were allowed to work in certain industries, going down from 60 hours a week to 54. This reduction of hours would lead to a reduction in pay for the workers in the Little Falls textile mills, ultimately being the primary reason for the strike. After this bit of exposition, the reader is given a further glimpse into some of the conflict encapsulated within the strike conflict itself, with an exchange between George Lunn and the Little Falls Chief of Police James Long over the issue of free speech being highlighted. In act one scene two, the reader receives even greater context regarding the history of the textile industry in Little Falls and what would be the catalyst to initiate the aforementioned law. This second scene touches upon the financial straits of the textile industry in this area, Helen Schloss being brought into the city by a group of well-off women called the Fortnightly Group to help fight tuberculosis in the city, and the horrifically catalyzing power of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911 in bringing about what would become known as the 54-Hour Law. The introduction of Helen Schloss in particular helps in painting a picture as to what exactly the immigrant population of the city was dealing with, that being abysmal living and working conditions on top of an antagonistic management. Crowded, poorly ventilated homes, rickety, dangerous structures, pollution, exposure to harmful chemicals, mistreatment by mill foreman, all things that Schloss witnessed in her investigation of the root causes of tuberculosis in the city. When the strikers eventually went on strike, Schloss would send a letter of resignation to the Fortnightly Club so that she may support them in various forms. Act two of Strike Story further explores the battle for free speech encompassed within the strike battle, soon after providing a deeper dive into the strike proper. The involvement of socialists from Schenectady, the formation of the strike committee created with the help of the Industrial Workers of the World, and the mass arrest campaign against the strikers carried out by the police and their privately hired deputies. As important as the events in the first act are, act two is where the historical narrative of the strike reaches at the least comes close to a climax as things begin to ramp up in this microcosm of class warfare. Act three is where the game truly begins to change, as the strikers and the strike committee look for new leadership in the aftermath of the mass arrests carried out only a few weeks after the strike began. The introduction of Matilda Rabinowitz as the new leader of the strike committee, the fight against the American Federation of Labor as they tried to undermine the efforts of the IWW, the involvement of labor legend Bill Haywood in garnering support for the strikers, and efforts to protect the children of the strikers are among several integral developments at this point in the story. Act three would ultimately bring us to the end of the strike, with a resolution officially being made between the mill owners and the strikers with the help of the New York State Labor Department in early January of 1913. Though legal battles would proceed for a number of the following months, the strike itself would come to an end. Something that needs to be appreciated about this play is that it’s based almost entirely on the factual history of what happened in this strike. Angela Harris thoroughly researched the proceedings of the strike and the relating preceding events, aiming for as much historical accuracy as possible while taking certain creative liberties, at least with the presentation of the events. Harris provides a bibliography of her sources, utilizing significant pieces such as first-hand accounts from Helen Schloss and Matilda Rabinowitz, works by Philip S. Foner and Little Falls native Richard Buckley, as well as a myriad of newspapers throughout New York State. Much of the dialogue of the prominent figures is taken directly from the speeches and articles of said figures, further sticking to the prospect of historical accuracy. The creative liberties come in the form of the character of the Woman Striker and the chorus. For the Woman Striker, her presence is for the purpose of personifying the collective struggle that these immigrant woman faced. The strike was, ultimately, all about her and those like her. This single character is made to encapsulate the pain and the determination of the masses of women who fought to ensure that she and her children could eat, that they could have even somewhat decent housing, and that they could improve conditions for their fellow workers. Elsewise, the creative liberties come in the form of the chorus. The chorus adds a new layer of storytelling to the strike, providing details that would feel rather awkward if explained directly by individual characters, such as listing off how much debt the mill owners were in prior to the strike or listing off the names of strikers and supporters who were arrested. The framing device of the chorus aids in explaining how this fight between labor and industrial capitalism came to be, serving as a welcome and a creative method of helping to inform the reader of the greater context of what this strike means. There’s even a musical element to this piece of theater. Throughout various points of this play, the chorus will sing brief sections of both popular music of the early 20th century, as well as various pieces of labor, socialist, and strike music. More notable pieces featured in this play include On Moonlight Bay, Bread and Roses relating to the Lawrence, Massachusetts strike that some tactics of the Little Falls strikers were borrowed from, Solidarity Forever, The Internationale, and The Marseillaise, one of the staple songs of the strike. This brief synopsis doesn’t do this story justice. The Little Falls Textile Strike is an event with a deep history that goes well beyond the confines of the story told in this piece, however what is being told here is well-structured, thoroughly researched, and as far as a written piece goes, an interesting and engaging read. Despite being a dramatization, there is much to learn from in reading Strike Story, and the same can likely be said for an actual theatrical production of this extremely significant story. There are several texts written about particular historical actors of this event, and the strike has had a handful of chapters dedicated to it in certain pieces, many of them being used as a reference in my own research and this play, however there’s a severe lack of pieces focusing solely on the strike. While my work aims to fill that gap as robustly and rigorously as possible, Angela Harris’ Strike Story holds the distinction as of the spring of 2024 of being one of the very few pieces dedicated to the strike as a whole, dramatic or not. This is an important piece that helps keep a relatively unknown piece of labor history alive, sharing a goal that I aim to contribute to with my upcoming book, and it deserves more attention. Copies of this play can be purchased on Amazon for just under ten dollars. AuthorJ.N. Cheney is an aspiring Marxist historian with a BA in history from Utica College. His research primarily focuses on New York State labor history, as well as general US socialist history. He additionally studies facets of the past and present global socialist movement including the Soviet Union, the DPRK, and Cuba. Archives April 2024 3/19/2024 Haiti: Trapped Between U.S. Guns, Death Squads, and the Next Colonial Invasion. By: Danny ShawRead Nowaiti is again breaking news. One of the top news stories in the world on March 12 was the alleged “cannibalism” of a Haitian gang. No different than the Department of Health’s equating Haitians with carriers of the AIDS virus in the 1980’s and Hollywood films such as The Serpent and the Rainbow, this disinformation campaign is a racist attack on the collective Haitian self-esteem. Such propaganda seeks to ideologically justify the impending fourth U.S.-directed invasion and occupation of Haiti in the past 100 years. But where there is repression, there is resistance. Haitian grassroots actors and their supporters around the world are saying no to both internal and external mercenaries usurping Haitian participatory democracy. As Haitian Bald Headed Party-affiliated (PHTK) paramilitary death squads rampage through Port-au-Prince, seeking to displace and massacre as many families as possible, Jake Johnston’s new book Aid State: Elite Panic, Disaster Capitalism and the Battle to Control Haiti is a valuable contribution to understanding the geopolitical origins of these “gangs.” The book provides context on why the Biden government appointed the unelected prime minister, Ariel Henry, in 2021 and then requested his removal from office last week as continued support for the illegitimate leader became untenable. Gangs or Mercenaries for Hire? Johnston’s page-turner is a necessary read for those new to Haitian studies, as well as those long familiar with the anti-dictatorship and anti-paramilitary struggles that Haiti has embarked upon in decades and centuries past. One thing is clear: the current paramilitaries, described in the mainstream press as “gangs,” must be analyzed on the historical continuum of U.S.-sponsored, state-affiliated armed groups, tasked with subduing the perennially “restless natives.” The preferred weapon of the mercenary gang bosses—Izo, Kempès, Barbecue, and others—is the torching of the communities they seek to subdue. Johnston points to the Michel Martelly administration (2011 - 2016) as being the first expression of the PHTK to use armed mercenaries to do their bidding. This assault on Haitian democracy, as personified by the politically-active populations of Belè, Lasalin, Solino, Delma anba, and the other ghettos of downtown Port-au-Prince, has reshaped Haiti’s capital city (spellings of Haitian words are in Haitian Kreyòl and not in the French colonial language). While early 2021 saw a mass movement that sought to topple the second expression of the PHTK dictatorship, headed by Jovenel Moïse, today armed and masked gunmen control some 80 percent of Port-au-Prince. According to the Displacement Tracking Matrix of the International Organization of Migration, 330,000 people have been internally displaced in Haiti, the majority of whom are children. Consistent with one of the principal themes of the book, I documented in visits to refugee camps at the end of January how the U.S.-sponsored Haitian state has yet to even visit the thousands of families sheltered in schools, alleyways, public plazas, and beyond. Aid State compiles 10 plus years of Johnston’s research in the Capital Beltway and 1,400 miles away, in the ancestral homeland of Haitian revolutionary leaders Dutty Boukman, François Makandal, and Jean-Jacque Dessalines. The backdrop of the work is a literary tour de force of the spellbinding mountains of the Grandans department, the crowded refugee camp of Titanyen, and the abandoned farms of the Grannò. The reader who has not visited Haiti in the past years as a result of what the Haitian people call the ensekirité planifye e òganize (planned and organized instability) is sure to shed a tear or two of nostalgia upon reading of the landgrabs of armed thugs employed by the PHTK. Haitian Patriots or Colonial Lackeys? The meat of the book provides a broad overview of the corrupt inner workings of Haitian state corruption beginning with the selection of Martelly as president in 2011 up to the present, and the U.S. government puppeteers who oversee the clumsy “politics as usual.” Johnston examines from the inside-out how the “aid state”—a state almost wholly dependent on thousands of private, foreign NGO’s—both consciously and unconsciously functions to disempower Haitians. Every page confirms what almost any Haitian will tell you: politics and “aid” are a rich man’s game which mocks the lives, interests, and dignity of Haiti’s 99 percent. Haitian young professionals searching to be of service to their country would have been militants of national liberation organizations in decades past. Today, much of this homegrown talent is compelled to follow the lure of some 10,000 NGOs that can pay salaries in U.S. dollars the Haitian left does not have access to. “Soft imperialism” contributes to an internal brain drain that discourages the upcoming generation from struggling for true Haitian sovereignty. Johnston shows how the Republic of NGOs—one accurate nickname for both pre and post-earthquake Haiti—is not organized to respond to everyday people’s needs. The product of years of investigative journalism, Johnston shows how the Republic of NGOs—one accurate nickname for both pre and post-earthquake Haiti—is not organized to respond to everyday people’s needs. Thoroughly researched chapters show how donors responding to the 2010 earthquake, including the Clinton Foundation, Citibank, and an entire cast of neocolonial characters, squandered $10 billion dollars, $1 billion of which was from the United States, constituting the “largest ever international mobilization to respond to a natural disaster.” A high percentage of that money was pilfered by Western companies who created fraudulent paperwork and looked out for corporate bottom lines, not the needs of the Haitian people. The chapter “The $80,000 House” explains with painstaking detail how Haitian Martelly’s government and his cronies, such as his childhood friend Harold Charles, worked with USAID and their U.S. contractors—including Thor Construction, Tetra Tech, and the CEEPCO company—in the wake of the earthquake to swindle Haiti’s population in the north. The Caracol-EKAM village was supposed to provide $8,000 homes for workers displaced by the earthquake who were the rank and file of the Clinton-USAID free trade or sweatshop project. After the vultures divided up the booty, each house turned out to have “cost” $88,000. What was supposed to be a community of 15,000 “culturally appropriate” homes for survivors of the earthquake ended up being 750 homes with major construction and sewage problems. This malfeasance was “the perfect encapsulation of everything wrong with our foreign aid system: the favoritism and corruption, the reliance on expensive foreign ‘experts,’ the lack of community consultation. Most of all, the houses stood as proof of how difficult it was to hold anyone accountable for their actions in Haiti.” Johnston, a Senior Research Associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, provides the necessary global—or more accurately U.S.—geostrategic context that explains how political unknowns like Martelly, Moïse, and Henry became the leaders of the nation, despite enjoying very little popular support. Johnston shows that the PHTK, the party of the U.S.-backed former president Martelly, is the principal Haitian actor at the center of the Guns, Gangs, and Neocolonialism drama that continues to play out. Interviews with former president René Préval, the head of the scaled-down UN mission Susan Page, and musician, hotelier, and former Martelly ambassador Richard Morse add to the entertaining, easily-digestible chapters. Aid State is further bolstered by chapters covering the theft of billions of dollars in Petro Caribbean funds by the Haitian state from Venezuela, and the 628,000 “zombie votes” from people who did not exist in 2016 that guaranteed victory for the PHTK and the United States’ man in Haiti, Moïse. Aid State ends with explosive new plot twists that help explain who was behind the July 7, 2021, assassination of Moïse that will shock even seasoned followers of all things Haiti. The Only Solution: Haitian Self-Determination The myriad threats and doxing to which the author has been subjected are the clearest proof he has exposed and touched the sensitive veins of colonial rule in Haiti. Like Jeb Sprague’s Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in Haiti, Mark Schuller’s Humanitarian Aftershocks in Haiti, Dada Chery’s We Have Dared to Be Free: Haiti's Struggle Against Occupation, and a phalanx of others, this is a book that belongs in every library of Haitian and anti-colonial studies. Johnston has been a valuable witness to an important chapter in the ongoing Haitian national liberation struggle. His lucid pen does justice to the continued mobilization of millions of Haitians against the Aid State. The myriad threats and doxing to which the author has been subjected are the clearest proof he has exposed and touched the sensitive veins of colonial rule in Haiti. I am an ethnographer who has filled up notebooks with notes on Haitian Kreyòl and culture for almost three decades. Since 2021, I have been following the paramilitary gang war on the long-peaceful and stable ghettos of Port-au-Prince. Jake Johnston’s rigorous research over the course of fifteen years has helped me better understand the present brutality that neocolonialism has produced. Johnston’s book is a necessary read for any friends and supporters of Haiti seeking to contextualize what is playing out in the korido (alleyways) and katyè popilè (oppressed communities) of Port-au-Prince as you read this article. Upon finishing this political science and journalistic gem, the reader wonders how, nearly one quarter of the way through the 21st century in the era of social media and identity politics, Haiti can so clearly remain a colony of the United States. Every U.S. government move in Haiti, from appointing prime ministers to organizing the next invasion, reflects their desire to maintain hegemonic control over Haiti. The years 1492 and 1697—the year of the “Peace of Ryswick” treaty which defined colonial ownership of the island the Taino natives called Ayiti—hemorrhage into 2024 as the masses of hungry and humiliated Haitians continue to dream of and fight for the Second Haitian Revolution. Until then, Haitian communities stand like David before Goliath, erecting their barricades to resist the onslaught of the paramilitaries and their foreign masters. Author Danny Shaw teaches Latin American and Caribbean Studies and International Relations at the City University of New York. He holds a master’s degree in International Affairs from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. As the Director and professor of the International Affairs Department at the Midwestern Marx Institute, he works to build unity and anti-imperialist consciousness. He is fluent in Spanish, Haitian Kreyol, Portuguese, Cape Verdean Kreolu and has a fair command of French, and works as an International Affairs Analyst for TeleSUR, HispanTV, RT and other international news networks. He has worked and organized in eighty-one countries, opening his spirit to countless testimonies about the inhumanity of the international economic system. He is a Golden Gloves boxer, fighting twice in Madison Square Garden for the NYC heavyweight championship. He teaches boxing, yoga and nutrition and works as a Sober Coach. He is a mentor to many, guiding them through the nutritional, ideological, social and emotional landmines that surround us. He is the father of Ernesto Dessalines and Cauã Amaru. He has also authored articles on Latin American history, boxing and nutrition, among other topics. You can follow his work at @profdannyshaw Republished from NACLA Archives March 2024 9/30/2023 Review of Immanuel Ness’s Migration as Economic Imperialism. By: Carlos L. GarridoRead NowThis review is adapted from the book launch presentation the author did for Immanuel Ness’s Migration as Economic Imperialism, which you can purchase HERE. The traditional Marxist critique of ideology has understood both the functional and epistemological dimensions of bourgeois ideologue’s claims. This tradition has always emphasized how ideas are both conditioned by the historical conjunctures and class positions of the people and institutions that materially embody them, but also – and equally important – how, under class societies, the economically dominant class, in whose control the rest of the political, juridical, and ideological institutions are under, has to necessarily distort the world’s understanding of itself so that the vast majority of people, whose class interests are diametrically opposed to theirs, can consent to this topsy turvy image of the world. As Marx and Engels noted early on in their theoretical development, If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process. This structurally necessary ideological inversion will later be labeled by Engels false consciousness, a condition where the people are unaware of the “real driving forces which move [them], [instead] imagin[ing] false or apparent driving forces.” This prevents bourgeois ideologues from properly understanding the world – it subdues their ability to obtain truth in their work. However, this is far from being only a question of errors in thinking, that is, the problem of ideological false consciousness, contrary to popular belief and those of the post-modernized Western “Marxist” specialists, is far from being merely one of consciousness. The inverted character of ideologue’s ideas is a reflection of an objective social order that requires its inhabitants to think of it in deliberately inverted ways. In short: the ‘error in thinking’ is an objective necessity for our social order, a social order that requires the generalization of mistaken views of itself for its own reproduction. The conventional bourgeois-imperialist narratives on migration and migrant labor, a phenomenon which affects around 3 billion people (approximately 40% of the world), is filled with these ideological inversions. Immanuel Ness’s book, Migration as Economic Imperialism, does an exceptional job at exposing how these ideas emerge of out the capitalist-imperialist system (and not out of some mythical disinterested and bias-free scientific observers). He shows us how these ideas distort reality, providing us with an upside-down image of the real world. And finally, he shows us who benefits, i.e., what class and social system is upheld by the systematization of these ideological contortions. The book is, in short, a quintessential example of what Marxist scholars should be doing in the battle of ideas: exposing the hollow falsity of bourgeois narratives, and replacing these with the truth – which, as we know well, is always on the side of the revolutionaries. While this last point might seem swaggering, it is not our fault, as Che Guevara is often attributed to have said, that reality is Marxist. The conventional imperialist narrative on migrant workers holds that they benefit the global economy, the global north countries of destination, and the global south countries of origins. Through remittances and the skills migrant workers obtain in the global north, so the imperialist narrative goes, they can help develop their countries of origin. Remittances are painted as “a leading form of economic development for poor countries” by International Development Agencies, the World Bank, and other imperialist institutions. After the migration boom of the 1990s that followed the overthrow of the USSR, the increased flow of remittances led bourgeois specialists to hold that this was a far more preferrable alternative to the old school ‘foreign aid’ that kept poor countries dependent on rich ones (the system that devised mechanisms of debt trapping and structural adjustment programs that kept global south countries poor and indebted, of course, was never questioned). In addition to remittances, the conventional imperialist narratives held that a stratum of higher skilled migrant workers were capable of developing new skills in the global north. These skills, so the myth goes, are taken back to the origin country and used to fuel their development and fight poverty. Are these narratives true? Do they actually correspond to the reality they attempt to explain? As you could’ve guessed it, they are about as true as any of the other capitalist myths. Which means, from the standpoint of a comprehensive analysis of the world as it actually exists, these claims are not true at all. In fact, their conclusions turn reality upside down; as the Athenian oligarchs once wrongly accused Socrates of doing, they are the ones that make “the worst appear the better cause.” They make migration, which benefits almost exclusively the elite of the imperialist countries, appear as a beneficial phenomenon for those poor souls forced into it by the conditions their countries have been subjected to after centuries of imperialist plunder and colonial and neocolonial domination. In reality, as Manny eloquently demonstrates, “remittances do not improve the standard of living for most inhabitants living in poor countries and do contribute to economic imbalances which engender higher levels of crime and violence.” “Remittances themselves,” as Manny shows, contribute to the erosion of the agrarian sector in southern economies as they constitute a form of rent for many residents in origin countries who are dependent on the continuing flow of remittances… [an] unreliable source of income.” Additionally, even when certain migrant workers obtain new skills in the global north, many of them do not return home – skilled migrant workers, as Manny notes, “are more likely to be provided with legal status than low-wage workers.” This leads to what some scholars have called ‘brain drain,’ the systematic flight of skilled workers, scientists, and technicians from their countries of origin in the global south (where they often got their education) to the countries of the imperialist global north. However, even when these skilled workers do go back, Manny demonstrates that they often end up working in “niche economies which do not contribute to improving the lives of most residents there but are directed to building networks with international business … that benefit a small fraction of elites as the majority of inhabitants remain mired in poverty.” So, for the imperialized countries of origin, where exactly are the benefits of migration? Besides the outliers in the elite that are benefited, the reality is that there are none. “If migration were beneficial to development [in countries of origin],” as Manny notes, “then countries with high migration would not be suffering the highest poverty rates, or would at least be seeing improvements outstripping those countries that were not following a migration-development strategy.” The evidence shows that the opposite of the conventional migration-development paradigm is true – migration helps to keep poor countries poor while enriching rich countries with a pool of cheap labor that they can superexploit. “The ten-leading remittance-receiving nations,” for instance, “are amongst the poorest states in the world.” “The primary dynamic of migration,” as Manny shows, “is rooted in the political economy of imperialism, which subordinates poor regions of the Global South.” Contemporary migration is, therefore, a product and central component of imperialism. It provides for imperialist countries, whose rates of profits with their national working class have been on a steady decline, a cheap pool of labor to superexploit. These are workers, many undocumented, who are forced to break with their families by the hundreds of millions in search for jobs that pay them pennies on the dollar of the already exploited global north workers. They frequently take up the most dangerous jobs and are forced to do these under the most precarious conditions, with very little bargaining power. They are often the recipients of xenophobic attacks and derogatory racist remarks, a phenomenon produced by the elite of the global north to convince their native workers (themselves struggling to get by), that their enemy is the migrant, not their boss. An interesting paradox arises here: while migrant workers have become an indispensable component of the imperialist economies for which they provide a cheap pool of labor to superexploit, these same workers are treated with the utmost expendability – evidenced in their working conditions and racist treatment. This is a phenomenon some scholars have called the ‘dialectics of superfluity,’ where human life and labor becomes simultaneously indispensable and expendable for capitalism. It is a condition that, while general in the working class, is intensified in migrant workers and oppressed peoples. Things don’t have to be this way. In fact, it is impossible for them to continue this way forever. The world and everything in it are in a constant state of flux, where all is interconnected to all and contradiction functions as the engine of historical motion. These objective contradictions in the global capitalist-imperialist economy contain the kernels for their own supersession. The interests of migrant workers and workers in the global north are the same. Both are fighting against the same global capitalist elite. It is this same elite that exploits and oppresses them both, even if it does it to one with more intensity than the other. The interests of workers of all countries, migrant or not, are found in uniting with their class against the parasitic rulers of the world – those who destroy humanity in their pursuit of profit. As time passes and these contradictions intensify, we are seeing workers coming together to fight. We are seeing the embryonic development of class consciousness – and sooner or later – we will see in mass the moderate demands James Connolly heralded in 1907: “We only want the earth.” Watch the book launch event for Migration as Economic Imperialism below: Author Carlos L. Garrido is a philosophy teacher at Southern Illinois University, Director at the Midwestern Marx Institute, and author of The Purity Fetish and the Crisis of Western Marxism (2023), Marxism and the Dialectical Materialist Worldview (2022), and Hegel, Marxism, and Dialectics (Forthcoming 2024). Archives September 2023 9/11/2023 Book Review: Vijay Prashad and Noam Chomsky's 'The Withdrawel.' Reviewed by: Edward Liger SmithRead NowSummary and AnalysisLast year in the summer of 2022 a wonderful friend named Debbie sent me a copy of Noam Chomsky and Vijay Prashad’s new book The Withdrawal. A year later I finally got the chance to sit down and read it (sorry it took me so long Debbie) and I was not disappointed as this text provides an excellent history of the major events and developments that have taken place within Western Capitalist imperialism throughout the last forty years or so. Those looking for a dense historical text will be disappointed as The Withdrawal is actually a transcribed conversation between Prashad and Chomsky, but this makes it a quick and easy read, perfect for beginners setting out to understand modern American policy and geopolitics. Going into this book I was curious to see how Chomsky and Prashad reconciled their views on existing socialist countries. Prashad is someone I’ve always admired for his ability to stand up for existing socialist countries and his refusal to parrot U.S. State Department talking points about countries like China. Chomsky on the other hand, has always provided brilliant critiques of the American empire, but has a tendency to sound like a mainstream liberal propagandist when the topic of the Soviet Union or Leninism comes up. However, it seems that Chomsky may be turning over a new leaf at the ripe age of 94 as attacks on China, Vietnam, and other existing socialist countries are notably absent from this book. The Withdrawal provides an excellent summary of the American Empire going back thirty years at least, and it does an incredible job of placing the major geopolitical events of the past few decades within their proper historical context. By example Chomsky’s analysis of the 9/11 terror attacks doesn’t begin on September 11th 2001. Instead he details the millions of dollars that were funneled into Osama Bin Laden’s terrorist group known as the Mujahideen by the United States after the Soviet Union occupied Afghanistan in an attempt to stabilize the country. Through this historical analysis Chomsky reveals how the U.S. empire created the forces who carried out 9/11, then used 9/11 as justification to invade two countries, Afghanistan and Iraq, who had nothing to do with the attacks on September 11th. In fact, the U.S. waged war against Taliban and Iraqi Governments that were actually enemies of Osama Bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda group, an outgrowth of the Mujahideen. Notably absent from Chomsky’s analysis is the claim so often made by Western academics that Soviet imperialism in Afghanistan was just as bad as American imperialism. Instead, Chomsky admits that most Afghans see the era of Soviet occupation as the most hopeful time in the country’s history. The Soviet soldiers fought bravely on behalf of the Marxist Democratic Government in power at the time against U.S. backed terrorist groups like the Mujahideen. They also helped the Government build factories, hospitals, infrastructure, and launch literacy campaigns teaching people to read even in the impoverished rural regions of the country. The U.S. on the other hand, dumped money and arms into Jihadist extremists who would throw acid on the faces of literacy workers and women who dared to walk outside without being covered head to toe. Thankfully, The Withdrawal avoids falling into the Western myth that tries to conflate Soviet and American imperialism as equal evils. And this may be due to the influence of Prashad, who has said in another book, Washington Bullets, that the CIA makes a concerted effort to conflate Soviet foreign policy with the worst acts of Western imperialism Similarly absent from the book are any attacks against the People's Republic of China (PRC), which Prashad and Chomsky accurately say is providing a counterweight to the long-held hegemony of the American empire. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRICS) were created to counter American imperialism through cooperation and economic development, not to rival American imperialism through exploitation and debt trapping. The authors refuse to fall into the Western trope of dismissing everything that the PRC is doing as “authoritarian” or “imperialist” as so many academics tend to do. Instead, they take a measured and fact-based approach to looking at the foreign policy of the PRC, which ends up making socialist China look pretty dang good. The book covers four core topics including Vietnam and Laos, 9/11 and Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. It will be an enlightening read for anybody who believed the mainstream media myths surrounding these major events. Chomsky brilliantly counterposes the facts of what actually happened in these four wars, to the mainstream media myths that were created to justify them. He also explains how the empire’s justification myths have morphed over time from the war against communism, used to justify the horrific bombing campaigns against Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, into the war on terror, used to justify the invasions of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya (as well as Syria although it’s not discussed thoroughly in The Withdrawal). In totality the book provides a fantastic summary of American imperialism since World War II, and I would recommend that beginners in the field of geopolitics read this text in conjunction with Prashad’s Washington Bullets that I mentioned earlier (After you read Imperialism the Highest Stage of Capitalism by Lenin of course). The Withdrawal is an easy read and it is not cluttered with hundreds of academic sources, but it is filled with the knowledge of two academics who have spent most their lives studying the U.S. Empire. Critique My criticisms of The Withdrawal are contained to the explanations given by Prashad and Chomsky as to WHY the U.S. carries out the murderous and imperialistic policy that it does. For one, the authors use the analogy of the Godfather to explain U.S. policy, arguing that since World War II the U.S. has held unrivaled and unprecedented power on the global stage, allowing them to act like a mafia, breaking the knees of anybody who goes against their interests. I agree with this description of American power, and I find the Godfather to be a useful analogy for how the U.S. conducts foreign policy, constantly ignoring international law in order to violently protect their own economic interests. Where I disagree with Chomsky and Prashad is when they say that American Policy is “rooted in a settler-colonial culture” or history. Make no mistake American policy is ROOTED in the mode of production, in the economic system of capitalism. America is not a uniquely evil country where people are born with some kind of innate drive to conquer foreign lands. Rather, we are a country of working people who are dominated by multinational corporations and finance capitalists that deceive the public in order to use them as pawns for advancing their global interests. It is not an attitude held by the American public that drives imperialist aggression, it is the incessant need for capital to expand, and the drive for surplus value inherent to the capitalist mode of production. The U.S. did not invade Iraq because Americans are a bunch of settler colonialists who wanted to seize a random country in the middle east. The U.S. invaded Iraq because the Koch brothers and other capitalists wanted Iraq’s oil. That is what American imperialism is rooted in, the need for constant expansion and increased profits which results from the capitalist mode of production, the basis for American society. And it is only through transforming this mode of production into a socialist one that we can bring a halt to American imperialism. Labeling the American working class as “settlers” will simply not achieve this goal. In fact, America’s settler colonial attitude and history, to the extent that it has existed historically, is itself rooted in the capitalist mode of production, not the other way around. It was the expansion of capital that brought European settlers to America in search of new land, labor, and resources; and it was capitalism that incentivized the mass genocide of the native populations. As Karl Marx brilliantly details in Capital Volume I, in order for capitalism to work it requires a large population of workers who do not own their own means of production or produce their own means of subsistence (food and other things humans need to survive) and thus are forced to sell their labor power to capitalists in order to survive. When European settlers got to America the native peoples already had their own mode of production and produced their own means of subsistence, and thus they needed to be wiped out by the settlers, or divorced from their own means of production and subsistence, in order for capitalism (and the bourgeois form of slavery seen in the American south) to take hold as the dominant mode of production. The genocidal settler colonial culture of European settlers at the time was rooted in the capitalist mode of production and its incessant need to expand. To say that American imperialism and the expansion of capital is rooted in a settler colonial attitude or culture is to flip reality on its head. Although, the capitalist mode of production has certainly benefited from such attitudes. Additionally, over 500 years have passed since European settlers first came to America. The U.S. is no longer a settler colonial project akin to the apartheid state of Israel, where every day native Palestinians are being forced off their land to make room for new Israeli settlement. It cannot be said that a settler colonial attitude has carried over hundreds of years later, and now acts as the motive force of American Imperialism in the year 2022 (the year the book was published). From the Marxist perspective, settler colonial or American exceptionalist attitudes stem from the mode of production, and in turn help to condition the mode of production. By example the attitude of American exceptionalism has been produced and maintained by the ruling economic class of capitalists in order to get the American people on board with their regime change wars. American exceptionalism is rooted in the capitalist imperialist system, and in turn helps to keep that system churning. Again, to say that U.S. imperialism is rooted in an attitude of American exceptionalism or settler colonialism is to flip reality on its head. Chomsky has never claimed to be a Marxist or dialectical materialist, and so I was not surprised to see him make this mistake. Prashad however, does come from a Marxist-Leninist tradition similar to myself, and I hope that he gets a chance to read this review and reconsiders his use of the word rooted when it comes to describing attitudes of American exceptionalism and settler colonialism. Regardless, The Withdrawal is a fantastic text from two intellectuals who I deeply admire. It is filled with information about American Imperialism that has been systematically withheld from the American public by the American ruling class of capitalist, bankers, shareholders, and neoconservative/neoliberal politicians. I would recommend this text to any Americans who want to know what our government has been doing around the world in our name for the last 75 years or so. Author Edward Liger Smith is an American political scientist (with a focus on Geopolitics, Socialist Construction, and U.S. health care), wrestling coach, and Director of the Midwestern Marx Institute for Marxist Theory and Political Analysis. Archives September 2023 9/9/2023 Decoding the Complexities of Culture: Review of 'Culture' by Terry Eagleton. Reviewed by: Jacob JoshyRead NowCulture is an “exceptionally complex word”, says Terry Eagleton, and as constant agents who interact with it in our daily affairs, we know how complex it is to write a book about culture, that too in less than 200 pages. Terry Eagleton, in his book 'Culture', puts forth a similar attempt, and one can easily say that he has succeeded. Eagleton starts his book with a brief preface where he lists out his intentions, that this book in its totality "sacrifices any strict unity of argument to approach its subject from several different perspectives." Terry Eagleton's central argument is that Culture is a "social unconscious", and to cement this argument, he takes the help of thinkers like Edmund Burke, Johann Gottfried Herder, T.S. Eliot and Raymond Williams. The author also takes an anticipatory bail in the preface itself about the overwhelming amount of "Irish motif" running throughout the book, in his attempt to build this central argument. The book is divided into five chapters, with each chapter dealing with a different aspect with which Eagleton wants his readers to engage. The first chapter titled 'Culture and Civilisation' talks about how culture is an integral part of human civilization, and further about the contrasts and similarities between the two. Eagleton makes a pertinent observation about how the usage and the meaning of the two words - Culture and Civilization - have changed starting from the premodern times to our modern age. The author then elaborates on his view about the dual nature of culture and civilization; that is, how both seem to be normative and descriptive at the same time. Eagleton also makes some interesting remarks about the links between the origins of the notion of 'culture' as such and the onset of industrialization. The second chapter, 'Postmodern Prejudices' is a precise commentary on the intricacies caused by the interaction of postmodernity and culture. Eagleton uncovers how the postmodern slogan of ‘inclusivity’ masks differences, and argues that rather than inclusivity, what we need is ‘unanimity’. "Different viewpoints," Eagleton writes "are not to be valued simply because they are different viewpoints." Postmodernity's "self-appointed censors," who are ignorant of how political opinions are formed, readily remove all discussions of political movements from the forefront and replace them with just political correctness arguments, which tend to diffuse conflicts and frame economic and political issues as cultural ones alone. Eagleton also concludes that contrary to the claims of culturalists, "Culture is not identical with our nature" but it is of our nature. Eagleton's main cultural theories and findings are largely contained in the third chapter, "The Social Unconscious." He writes "This social unconscious is one thing we mean by culture". With references to Freud and Lacan at the beginning of the chapter, the reader might assume that Eagleton is aiming to develop his arguments from a psychoanalytical standpoint. However, it was only a viewpoint the author was attempting to implant in the readers' brains. The chapter heavily relies on the ideas and teachings of two thinkers - Edmund Burke and Johann Gottfried Herder - who were both vocal critics of colonialism and for whom culture is more essential than politics. Eagleton finds that Burke "prizes order" while Herder "values freedom". The author says that the "unfathomable specificity of human affairs" is what we know as culture and juxtaposes Antonio Gramsci's hegemonic power with Burke's view on culture. In the later parts of the chapter, he elaborates on the evolution of language and culture. If, till now, the chapter mainly depended on conservative thinkers to make the case of 'social unconsciousness, Eagleton goes to Raymond Williams towards the end of the chapter to explain the radical version of it. He notes that, unlike Elliot, for Williams, culture essentially is unplannable and "always a work in progress". Up until this point, the book dealt with issues related to the theory of culture. In the fourth chapter, suitably titled "An Apostle of Culture," Eagleton shifts his focus to the "summary of the thought" of Oscar Wilde. Eagleton notes that both Wilde and Burke were Irish, which made them vocal critics of Britain's colonial aspirations, and "ended up biting the hand that fed them". Unfortunately, the author didn't touch the realms of dependency theories which almost and mostly deals with similar complexities. Eagleton cites that being Irish necessarily contributed to the formation of Wilde’s career and his openness to the idea of modernism; “To be marginal to a language and culture” he writes “is also to be freer than the natives from its ruling forms and conventions, and thus to be less hamstrung by them”. For Wilde a known proponent of ‘art for art sakes’, notes Eagleton, art wasn’t a “question of fleeing from life into art” but on the contrary a “question of turning one’s life into a work of art”. Eagleton also put forth a striking comparison of Wilde with Marx, even though there was a fundamental difference in their end goals. Wilde sees individualism as the goal of socialism which is diametrically opposite to Marx’s views. But what Eagleton finds is that the “Romantic sense of the richness and diversity of individual lives” seen in Marx is similar to Wilde, and both of them aspired for a world without labour so that people have “time for the more vital business of self-development”. The last and final chapter 'From Herder to Hollywood' talks about the evolution of culture through modern times. Culture, Eagleton notes, came to prominence as a "critique of industrialism, but also as a rebuke to the notion of revolution." He further writes that "it became a key concept in the language of Romantic nationalism." This form of romantic nationalism can be traced to the works of D. H. Lawrence and Friedrich Schiller. This recent development can be seen in Jane Austen's writings, where 'politeness' emerges as a substitute for 'culture.' Over this period, Eagleton observes that art also found a new audience, the common people, and can be attributed to the 'new array of social institutions' that rose post the industrial revolution. This form of romantic idea, warns Eagleton like any other brand of ethics pave the way for the dogmatic version of cultural nationalism. Also, during this time, poets and artists took centre stage in recently evolved concepts of liberalism and democracy. He finishes with a critique of the latest addition to capitalist modernity in the form of cultural industry. The book ends with a brief concluding chapter 'The Hubris of Culture', which neatly sums up all arguments presented over the last five chapters. To tie things up, Eagleton warns that the central question that confronts the new millennium is not cultural but a political one. The compounded nexus of culture is not fully explored in Eagleton's book, nor does he make a similar claim in his book. However, what distinguishes Eagleton's study of culture from that of other cultural critics or postmodern thinkers is that the core of Eagleton's criticism revolves around labour, which, according to Karl Marx, is the only "progenitor" of civilization. A great deal of his analysis deals with the origin of the notion of culture and its relationship between colonialism, and its subsequent evolution into an academic discipline that was "contaminated to its core by racist ideology". Like an ethnographer, Eagleton transcends back into time and age, and studies literature, theory and thought to demonstrate this "unholy alliance between colonial power and nineteenth-century anthropology". Although he is conscious of the cultural industry's power, he does not respond in a puritanical manner and sees the widespread popularization of literature and art as a negative development. He acknowledges that modern industry also made it possible for millions of people to consume what was prohibited to them, however, the only objection to this industry phenomenon is the profit motivation that drives this cultural upsurge. And the remedy he offers is the collective consciousness that relies majorly on strong radical political movements. At a time when we are overwhelmed by advertising brands and dopamine inducing Instagram content, Terry Eagleton's short book provides us with a lot of insights and perspectives to tackle this critical juncture of human civilisation, and must be read by any student of social sciences to grasp and overcome this harsh reality. Author Jacob Joshy is currently pursuing MA economics at South Asian University, Delhi Archives September 2023 8/24/2023 Book Review: ‘Cancel This Book’ Asks for a Return to Revolutionary Class Analysis By: Danny ShawRead NowDan Kovalik’s book, Cancel This Book: The Progressive Case Against Cancel Culture (2021) Cancel This Book: The Progressive Case Against Cancel Culture, by Dan Kovalik (Hot Books: New York, 2021) Academic and activist Dan Kovalik’s new book, Cancel This Book: The Progressive Case Against Cancel Culture, was written on the frontlines of the twin struggles of our time, the class struggle and the fight for Black liberation. Reading it brought me back to so many magical and contradictory movement moments that I could not resist writing a review. ‘White People Go to the Back of the March’ On the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Day in 2017, thousands of protesters took to Fifth Avenue and the frigid streets of New York City to demand criminal charges against the police who murdered Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge; Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota; and hundreds of other unarmed Black and brown men. Some Black Lives Matter march marshals had determined that Black and brown families and activists—presented as the only real victims and fighters—would march in the front. White people—presented as all equal benefactors of white supremacy and white privilege—were assigned to march in the back, separated from the youthful, militant front. It was a strange scene. Forty-nine years after the U.S. state assassinated Dr. King for risking his life to organize a multiracial movement against white supremacy—and in his final months, a Poor People’s Campaign against the capitalist system—surely he would find it curious we no longer needed outright white supremacists like Bull Connor or George Wallace; we were now capable of segregating our own marches.

When I picked up Kovalik’s new book, I was intrigued by his biting class analysis of the similar experiences he had. In chapter 2, “Cancellation of a Peace Activist,” he writes directly about being a participant on the frontlines of the BLM movement in Pennsylvania, ducking and dodging police batons as organizers collectively figured out their next strategic moves. Kovalik, a union and human rights lawyer and professor, based out of Pittsburgh, dives deep into the contradictions he and so many others experienced. Kovalik slams both the arrogance of isolated white anarchists whose faux militancy puts all protesters at risk, as well as the bullying tactics and racial reductionism of some radical liberals. This took me back to the explosion of protests following the police murders of Eric Garner and Michael Brown in 2014, which brought millions of people into the streets to denounce the epidemic of police terror in Black and brown communities. Millions were in motion and different political tendencies vied for leadership. Kovalik examines key lessons to be drawn from the almost decade of collective experience we have as a movement in what came to be known as “Black Lives Matter.” This is but one must-read chapter in Kovalik’s exciting new book. Woke Capitalism Kovalik’s book is an expose of Woke Capitalism and the cancer of cancel culture. While millions took to the streets to stop President George W. Bush from invading Iraq, the peace movement was eerily silent when Barack Obama, the country’s first Black president, became “the drone-warrior-in-chief, dropping at least 26,171 bombs in 2016 alone.” (pg. 109) He critiques the peace movement for going quiet every time a Democrat is (s)elected to the oval office.