|

In the wake of the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent protests and calls for change that followed, an interesting solution was brought up and encouraged, the call to buy from black businesses. While black businesses are indeed a way to grow wealth for the black community, they are in no way a solution to the broader source of oppression. In order to truly liberate the black community from the chains of racism, generational poverty, state oppression, and exploitation, it’s not enough to encourage the entrepreneurship of only a few people, one must address it from a collective and anti-capitalist approach. Only with socialism will the black community truly be eliminated from the systemic racism capitalism has weighed over them. When speaking about black entrepreneurship one is often met with rosy words of praise, all across the political spectrum, even so called “progressives” and “intersectional feminists” gush at the idea of buying from black owned businesses (BOBs). But let us not be fooled, small businesses are not inherently better than corporate behemoths. In fact, small businesses can and usually are worse for workers than larger businesses, including conditions such as offering worse benefits, lower wages, and being exempt from worker protections. This isn’t a defense of big business but a criticism of businesses overall. Small businesses and mega-corporations both exploit their workers. However, small businesses, unlike mega-corps, have a quaint rosy glow which excuses them from the harsh scrutiny received from larger companies. It doesn’t matter who’s in charge of the business or if the company is large or small. Businesses functioning in the traditional structure are still exploitative; the worker continues to not receive the full value of their labor and are forced to rely on the will and the mercy of the boss to not starve. Moving on, the origins of black capitalism and the related “opportunity zones” have been a meager scrap thrown to the black community in a lame effort to eliminate the effects of systemic racism and generational poverty. The origins of modern Black capitalism lay in Nixon’s “Southern Strategy”. Instead of actual racial and economic justice such as desegregation, more public sector jobs, anti-discrimination measures, etc., mild tax incentives and breaks was the solution to racial ghettos and oppression. These meager crumbs tossed to the black community allowed Nixon to oppose vital economic reforms championed by Civil Rights activists and to crack down on the black community in other ways (most notably the War on Drugs and the War on Crime). In an effort to undermine important economic and racial reforms Nixon started spouting free-market and libertarian talking points, arguing that capitalism was the natural cure of racial ghettos and that black people should “help themselves.” Such rhetoric appears in his Acceptance of the Republican Nomination for President Speech “Instead of Government jobs and Government housing and Government welfare, let Government use its tax and credit policies to enlist in this battle the greatest engine of progress ever developed in the history of man-American private enterprise.” Black-Americans were thus wished good-luck before being shoved down the meat grinder that is capitalism, often put in a position where they are the ones worse off after every financial crisis and capable of gleaning only the tiniest bits during the good times (especially in comparison to their white counterparts). Decades have passed since the Nixon administration and both parties have continued to champion black capitalism while either cutting social programs or giving very meager assistance. Black capitalism, while it may have started with Nixon, eventually morphed to “enterprise zones” under Reagan, “new market tax policies” with Clinton, and “promise zones” by Obama. All of whom have continued and put into place brutal neoliberal policies where BIPOC typically bear the heaviest burden and draconian treatment of felons, especially those on drug charges (which are disproportionately black), creating a cycle of poverty for generations to come. The problems that plague the black community are not a lack of entrepreneurship or an insufficiency of capitalism, rather, it is capitalism itself that continues to dig the black community into an even deeper hole. It was “entrepreneurs” and banks run by capitalists who were responsible for shoving subprime mortgages down the throats of black borrowers, resulting in 53% of all wealth in the black community being wiped out, and by 2009 35% of black communities having zero or negative wealth. It is years of mass incarceration, housing discrimination, and red-lining which pushed and continue to keep the black community in poverty. None of the problems listed above can be attributed to the problem of a lack of “black entrepreneurship” or lack of capitalism. Rather, it is capitalism that is at the root of many of these problems. It was land developers and planners who decided to red-line neighborhoods in fear that having integrated neighborhoods would decrease the value of the neighborhoods, and thereby lower their profits. It was the private prison companies who lobbied the government for harsher and more draconian laws and sentencing to funnel more BIPOC into the prison system, which further ruined their chances of building any wealth, and thus made it more likely that they would return to prison – not to forget of course the many companies that rely on and use prisoners as free labor. Minority capitalism isn’t the solution to wider systemic problems caused by the capitalist system itself. The assumption of black capitalism is that it is possible for society – and especially Black Americans – to buy their way out of racism and oppression. This is an assumption that is verifiably false. It is a bandage upon an internal wound. It is neoliberalism’s way of co-opting an important movement and, like a leech, sucking out all the meaning of the movement. Additionally, “buying black” and supporting black capitalism is an incredibly individualistic approach to uplifting the black community. Black capitalism, as well intentioned as it seems, only uplifts a few members of the black community. True liberation is not adding a few members of the marginalized group to the oppressing group, rather, it is dismantling the system that creates thus conditions. Black capitalism lifts a few members of the community to the position of the bourgeoisie. Having a more diverse bourgeoisie, a more diverse group of people responsible for the suppression of the proletariat does nothing for the vast majority of people who face hunger, starvation, homelessness, poverty, and various other issues that intersect with their identity. The only solution is the dismantle of capitalism. What are examples then of anti-capitalist societies that have managed to drastically eliminate the legacy of systemic racism? The answer to that is Cuba. Cuba prior to the revolution used to be no different than the US when it came to race relations. Afro-Cubans faced widespread discrimination and segregation. They were given the worst jobs, housing, and education (if any at all). However, immediately after the revolution the newly established government set to work immediately to combat all traces of systemic racism. Anti-racist measures were enforced both legally and socially. In Cuba’s Constitution Chapter 1 Article 42 all people regardless of their identity(ies) are guaranteed equality before the law, in comparison to the US Constitution where such an explicit promotion of equality doesn’t exist. Furthermore, anti-discrimination doesn’t only exist as an empty statute but is constantly and vigorously enforced with militias in any location where black and mestizos could be denied equal treatment. A harsh contrast in comparison to the US where BIPOC are constantly being denied mortgage loans and/or given worse rates, poorer medical care, and denied jobs because of their race. While there’s no doubt that fully eradicating the legacy of systemic racism won’t be solved overnight and people will still hold onto many of their discriminatory beliefs even under a different economic system, in the transcendence of capitalism, the economic and material conditions that produce racial inequality and oppression will be abolished, a vital and necessary step to doing away with racism. Citations Baradaran, Mehrsa. Opinion | The Real Roots of ‘Black Capitalism’ (Published 2019). 1 Apr. 2019, nytimes.com/2019/03/31/opinion/nixon-capitalism-blacks.html. Barnes, Jack. “The Militant - April 19, 2010 -- Affirmative Action Needed to Unite Toilers.” The Militant, 19 Apr. 2010, themilitant.com/2010/7415/741560.html. Coleman, Aaron Ross. “Black Capitalism Won’t Save Us.” The Nation, 24 May 2019, thenation.com/article/archive/nipsey-killer-mike-race-economics/. “Cuba’s Constitution of 2019.” Constitute Project, 4 Feb. 2020, constituteproject.org/constitution/Cuba_2019.pdf?lang=en. Mallett, Kandist. “The Black Elite Are an Obstacle Toward Black Liberation.” Teen Vogue, 30 Oct. 2020, teenvogue.com/story/black-elite-racial-justice. Martinez, Carlos. “20 Reasons to Support Cuba - Invent the Future.” Invent the Future, 13 Jan. 2014, invent-the-future.org/2013/07/20-reasons-to-support-cuba/. Prescod, Paul. “‘Black Capitalism’ From Richard Nixon to Joe Biden.” Jacobin, 18 May 2020, jacobinmag.com/2020/05/black-capitalism-joe-biden-unions-class. “Speeches by Richard M. Nixon: Acceptance of the Republican Nomination for President.” US Embassy, 8 Aug. 1968, usa.usembassy.de/etexts/speeches/rhetoric/rmnaccep.htm. About the Author:

N.C. Cai is a Chinese American Marxist Feminist. She is interested in socialist feminism, Western imperialism, history, and domestic policy, specifically in regards to drug laws, reproductive justice, and healthcare.

1 Comment

In the days after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer in the United States, massive revolts spawned in that country and have travelled fast around the world, getting the center of international attention and gaining massive support. Among those who comment on these events, there has been much (and certainly, there has to be) insistence on the fact Floyd’s murder is not merely an isolated act of racist hatred: it is recognized that racist violence is a systemic or structural issue[1]. Nonetheless, it is very important to clarify what that means. What is that system in which racial violence is framed (inside and outside of the United States)? If this is not explained, pointing out the structurality of racist violence remains at a level of generality in which, without being less true, it ends up being something banal. Of course, I do not pretend to provide an exhaustive analysis or a definitive answer here. I would like to insist, however, that it is crucial for this explanation to understand that, like all phenomena in our society, racism is a historical phenomenon, and a specifically modern one[2]. It is a mistake to believe that it has been present exactly as we know it in all societies; yes, there has always been a difference between one’s own group and foreigners, along with a hierarchy of value between “them” (barbarians) and “us” (civilized), which can include differences based on physical or phenotypic traits. However, racism, the idea that there is a natural fatality, race, that is much more deeply rooted in the being of individuals than any archaic caste, and that innately entails a state of moral, cultural and intellectual inferiority and a servile condition, is a legacy of modern colonialism and the system of slavery that it inaugurates[3]. One must also understand that, contrary to what many liberal advocates of Western civilization maintain, slavery was not some “pre-modern” heritage. Slavery in Europe had been abolished in the 13th century, and in the Islamic world even earlier. Slavery will resurface in the middle of the 16th century, when it is already crystal clear for the whole of society that it is something aberrant, and in a much more degrading way than in any other time in history (a slave in the Middle Ages or in the Ancient World did not inherit his condition by the color of her skin, and she had a much better chance of buying her freedom for herself or her family, and even of moving up socially), because of the interests of the new merchant class that was then beginning to emerge (that is: due to the economic need of cheap labor)[4]. Racism does not precedes slavery: racism emerges after decades of forced servitude, subject to the need for profit of the new capitalist class, to its need to appropriate land and human beings to generate wealth without cost overruns. It is the quasi-natural justification of the situation of oppression inherent to a system of expropriation and exploitation. The history of modern racism and colonialism goes hand in hand with the history of capitalism: they are the same history. That is why it is a mistake to think that capitalism is merely “an economic system”. Capitalism is, above all, a system of domination based on expropriation and exploitation. And that is also why, although it is correct to celebrate the awareness of the masses who, exercising their legitimate right to disobedience, unleash their indignation and furious protest[5], we must not remain complacent in the pure celebration of revolt (which without organization and a clear strategic route, always ends up fading away). Eliminating racist structural violence, overcoming the oppression of peoples of colonial origin and exploited labor throughout the world, requires thinking about a radical reorganization of the economic and political system that we call capitalism (to think, without fear, in its opposite). We must think and speak without fear of socialism, and think and speak without fear about how we must organize to overthrow the social class that to this day benefits from the most savage injustice. Regarding this reflection, I believe that Marxism (with 180 years of theoretical and practical experience in Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas) has much to contribute. Citations [1] In the case of the United States, this becomes evident to those who contemplate the figures and the systematicity with which the Afro-descendant population suffers this kind of violence by the punitive institutions of the state. In the case of Peru (my country), a similar argument could be made in relation to the mestizo and indigenous population. [2] See Allen, T., The Invention of the White Race (2012). Also, I. Wallerstein and A. Quijano, “América como concepto o América en el moderno sistema mundo”, in Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales vol. XLIV n°4, 1992. [3] See Losurdo, D., Class Struggle: A Political and Philosophical History (2015). [4] Indeed, it is interesting to see how European society, in the centuries before the restoration of the slave trade, had already generated institutions and normative resources to question the practice of slavery (the antislavery position of the theorist of absolute monarchy Jean Bodin can be contrasted with that of the “father of liberalism”, John Locke, whose defense of private property included a defense of slave ownership in the colonies). The Catholic Church and the monarchical state, despite all of their despotism, often played a positive role in this regard. It was against the “illegitimate” interference of these “illiberal”, pre-modern powers in regard to the administration of their possessions that liberalism as a doctrine would be born. See D. Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counter-History (2005), and for a more general history of “primitive accumulation”, see the first volume of Marx’s Capital. [5] See Celikates, R., “Rethinking Civil Disobedience as a Practice of Contestation – Beyond the Liberal Paradigm”, in Constellations Volume 23, n°I (2016). About the Author: Sebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Originally published in Disonancia: Portal de Debate y Crítica Social (Jun 4, 2020)

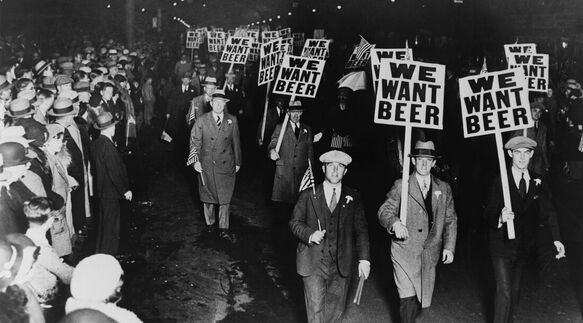

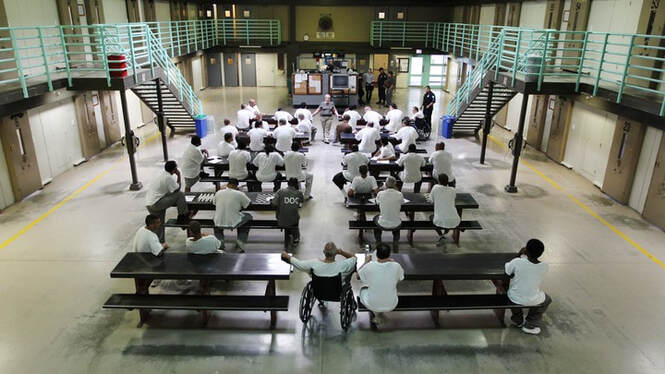

IntroductionIn US history the two largest spikes in the murder rate have happened during eras of drug prohibition. The first spike occurred from 1920 to 1933 during the prohibition of alcohol. The second from 1970-1990 when Nixon declared the war on drugs. From the very start, the war on drugs has been about suppressing the poor and the marginalized. And, even if it was about eliminating drug use and all the horrible issues related to it, such as addiction, mental health disease, poverty, and violence, it has proven a failure in stopping those as well. Instead, the war on drugs has worsened these problems causing more chaos, pain, addiction, and death. The war on drugs and drug prohibition as a whole has been completely ineffective at reaching its goals of eliminating drug use and the negative effects associated with it. HistoryAs ingrained as drug laws seem today, it was only in 1875 when San Francisco passed the nation’s first anti-drug law. The law wanted to stop the spread of opium dens and banned the practice of smoking opium. A federal law accompanied the San Francisco law, banning anyone of “Chinese origin” to bring opium into the country. The racist excuses didn’t end, the targeting of cocaine followed suit in 1909 when rumors began to spread that black men were getting high on cocaine and as a result were raping white women. These rumors allowed a mass hysteria to sweep the nation and anti-cocaine laws followed suit. Five years later in 1914, the Harrison Narcotics Act passed. While the HNA didn’t outright ban drugs such as cocaine, cannabis, and heroin, it expanded the government's ability to tax and regulate them. The goal being to tax drugs to the point of nonexistence. However, despite the HNA, cannabis still remained popular especially among the jazz and swing scene in the 1920s and 30s. At this point, Harry Anslinger, head of the Bureau of Narcotics and notorious for being racist even in the 1930s steps in. Anslinger warned the nation that jazz and marijuana created an opportunity for blacks to rise above the rest; and that it induced madness in Hispanic immigrants leading them to commit violence against whites. Then in 1937, Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act for the purposes of raising the prices of marijuana making it even more inaccessible. The same trends of reactionary backlash are shown in the 1960s and 1970s, amidst a variety of social movements but mainly the civil rights, and anti-war movement. These movements caused the rightwing who were unwilling to acquiesce to any of the demands to crack down on drugs which they knew would harm those communities. John Erlichman an assistant to the Nixon administration, even admitted in 2016 in an article by Dan Baum for Harper’s Magazine that racism and suppression of opposition to the Nixon administration was the reason why they further agitated the war on drugs. Stating, “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities…. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.” From the very beginning, drug prohibition existed to suppress a society’s underclass. While there are numerous supporters with good intentions the unpleasant roots do not simply disappear. Thus, supporting prohibition ignores the history of ruthless attacks against minorities and contradicts America’s values such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Economics: The Iron Law of ProhibitionRacist origins and intentions aside, even if the war on drugs started out by attempting to lower drug use and by extension to create a healthier society, it still would have resulted in a massive disaster. Simply banning drugs doesn’t stop people from using them. The perfect example of this is alcohol prohibition. While it is true that alcohol consumption dropped significantly in 1921 from about 0.8 gallons to 0.2 gallons, the rate sharply rose in 1922 to 0.8 gallons and continued on an increasing trend through the 1920s. Prohibition failed at lowering alcohol consumption for most of its duration and made the alcohol more potent. This is due to the Iron Law of Prohibition by Richard Cohen which states that the stricter the law enforcement, the more potent a substance becomes. Prior to prohibition Americans spent a falling share of their income on alcohol and purchased higher quality and weaker drinks. They also spent similar amounts of money on both beer and spirits. However, after Prohibition spirits replaced beer as the drink of choice for almost all consumption and production of alcohol. Hard liquor and spirits are more potent than beer and wine which made it easier to hide and transport. Liquor and spirits could also be sold to greater amounts of people. The largest cost in selling an illegal good is avoiding detection by the authorities. Weaker products like beer were too bulky and indiscrete. As a result of the law, the prices of beer rose more drastically than that of brandy and spirits (700, 433, and 270 percent respectively). Beer consumption and production all but disappeared with the exception of homemade beers. However, after prohibition was repealed total expenditure on distilled spirits as a percentage of total alcohol sales severely dropped and people returned to drinking beer and other milder forms of alcohol. The lesson gleaned from this experiment gone wrong is that prohibition is completely ineffective at reducing drug abuse and addiction. Prohibition is completely counterintuitive because rather than stopping people from using drugs it makes drugs more potent and more addictive which increases drug use. Black markets are like all markets, the profit motive is king, which means drug dealers want the biggest bang for their buck. Especially when the largest cost of buying and selling drugs on the black market are the social and legal consequences. In order to get the best deal, drug dealers must satisfy the demand of as many consumers and create new ones without getting caught. This means that they have a financial incentive to increase the potency of the drugs because stronger drugs are easier to hide and transport thus lowering the social and legal risks. Along with lowering the costs, more potent drugs are able to meet the demand of more consumers than weaker drugs. Take the example of alcohol, while a gallon of beer can only be sold to two people, a gallon of spirits can be sold to ten people. The seller makes more money selling spirits to ten people than only selling beer to two people. In the situation of transporting the drugs since beer is bulkier and satisfies less demand, there is more of a legal and social incentive to produce and distribute spirits. However, the Iron Law of Prohibition doesn’t only apply to distributors it also applies to the consumer. Take the example of a college football game, stadiums typically ban alcohol, as a result, college students who are typically beer drinkers now become hard-liquor drinkers. Since it's easier to sneak in liquor in a flask than it is beer bottles which are heavier and less discrete. While there certainly is a problem with drinking and alcoholism in the US, prohibition is simply not the solution. Drug Prohibition forces drug use and distribution to occur under a black market which creates more addictive and potent drugs. The results of Prohibition merely exacerbate the overdose crisis and line the pockets of drug lords. Expense of the War on DrugsThe War on Drugs is perhaps one of the largest scams in US history. According to the Center for American Progress, the federal government has spent an estimated 1 trillion dollars on the war on drugs, increasing every day since the 1970s. From 2015 the government has spent more than 9.2 million dollars every day to incarcerate people with drug offenses alone. The federal government isn’t the only party that spends outlandish amounts of money on drug enforcement. In 2015 alone states spent about 7 billion dollars on incarcerating people on drug-related charges. Georgia spent about 78.6 million dollars just to incarcerate people of color on drug charges, an amount that is 1.6 times more than the amount it spent on treatment services for drug use. However, enforcement isn’t the only cost, what happens once the person convicted of drug charges gets released? Their employment and economic prospects are ruined. For example, the Cato Institute estimated that the cost of the diminished employment aspects of felons ranges from about 78-87 billion dollars. In total the war on drugs costs the US about 51 billion dollars annually. That is 51 billion dollars every year for a crusade that has done nothing but destroy the lives of millions, rob Americans of their freedom, and create countless unproductive members of society. Bear in mind that there are many better alternatives to using 51 billion dollars for a racist witch hunt, a great alternative would be ending homelessness which would only cost about 20 billion dollars. Having access to a shelter would make it easier for people to get a job since most job applications require an address. Having a home would also encourage people to live in a stable supportive community where there would be support for them to go to rehab. In an era with greater wealth inequality and a growing deficit, hunting people down for doing what they want with their bodies should be the last thing on the mind of the state. Especially a state that is well known for committing horrible atrocities to minorities and reinforcing institutions such as Jim Crow and slavery which continue to leave a lasting scar on millions of people. Crime and PunishmentAside from taking away the right of every American the liberty to do whatever they want with their body, the war on drugs also punishes thousands if not millions by locking them up in a cage if even caught with a single trace of a drug, even something as innocuous as weed. In 2018 the U.S arrested more than 1.6 million people for drug-related charges, of those arrested more than 1.4 million were for possession only, and of those arrested for possession about 608,000 of them were for marijuana possession. However, the penalties are almost never distributed evenly, despite making up only about 13% of America’s population, blacks make up about 27% of drug arrests. Nearly 80% of people arrested for drug-related charges in federal prisons and 60% in state prisons are black or Latino. Prosecutors were also more likely to pursue mandatory minimum sentences for blacks than whites. In 2011 of those who received a mandatory minimum, 38% were black and 31% were Latino. However, despite unequal enforcement blacks and whites use and sell drugs at similar rates yet black people face harsher punishments if caught using drugs. The war on drugs is nothing more than an excuse to deny America’s problem with systemic bigotry. Rather than solving the problems arising from systemic racism, the war on drugs associated minority communities with drugs and poor behavior instead of actually solving these problems at their root cause. EffectivenessHowever, has locking up people for drug offenses actually reduced drug use and crime? The answer is no, drug overdoses have skyrocketed since the 1980s. The drug abuse rate has remained stagnant since the 1970s at 1.3 percent despite US spending on drug control significantly increasing since the 70s. The Center for American Progress adds that incarceration has shown to have had a negligible impact on drug abuse rates and in fact are linked with higher rates of overdose and mortality. Prisoners in the first two weeks upon release faced a mortality rate that was 13 times higher than the general population. The leading cause of death among these people is overdose. Incarceration is a traumatic experience for most people. In prison, violence is a constant presence by both inmates and guards. Many also face solitary confinement, a punishment so torturous that it’s been called out by the UN and has been proven to induce a variety of mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, psychosis, self-harm, and suicide. Upon release, all opportunities for decent employment are nonexistent, as are paths to being able to enroll in higher education, and not being able to live in public housing or to be able to buy a home. All of these factors create the perfect conditions for addiction and drug use. Contrary to popular opinion the substance itself only plays about a 20% role in addiction. The Office of the Surgeon General found that only 17.7% of nicotine patch wearers stopped smoking. While 20% is still significant it nonetheless shows that chemical hooks aren’t the overwhelming reason why people are addicted and that there are greater causes of addiction outside pharmacology. In regards, of the 80% gap the psychological state of the user is perhaps more influential than the chemical hooks. According to a study conducted by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente called the “Adverse Childhood Experiences Study” the scientists looked at ten different traumatic events that could happen to a child such as physical and sexual abuse to the death of a parent. Discovering that for each traumatic event the child’s chances of becoming an addicted adult increased 2-4 fold. They also found that nearly two-thirds of injection drug use was the result of childhood trauma. Addiction isn’t the result of bad morals it’s the result of pain. Of course, people with pain will try to numb it whether it's as simple as taking an aspirin for a headache, drinking after work after a rough day, or injecting heroin to forget about a traumatic event. The only difference is that society condones the first two while tossing the third one in jail. By criminalizing people with substance abuse disorders society is criminalizing mental illness rather than treating it. Therefore, when society throws these people who already deal with unbearable amounts of pain and which resort to self-medication with illicit drugs, they are not getting rid of the problem, they are aggregating it by creating more suffering for the person who is already in pain. ConclusionThe War on Drugs has been a disaster of epic proportions from locking up millions of people and ostracizing drug users, to stripping Americans of their liberty to do as they please with their body. The War on Drugs dehumanizes drug addicts who most likely faced some sort of traumatic event in their life and further exacerbates the problem by adding more trauma via incarceration and the denial of support upon release. All of this added pain makes the susceptible person more likely to self-medicate. Since safe versions of the drugs are gone because of prohibition they have to rely on shady dealers peddling products with questionable quality and deadly potency as a result of the Iron Law of Prohibition. And if they get caught with the substance, they’re thrown into prison which creates a downward spiral. Prohibition regards drug users as below human and only worthy of contempt. It is only care and community that help people get over their problems. Thus, repealing drug prohibition would stop the stream of both non-problematic drug users and drug addicts being imprisoned. Thus, encouraging people to seek medical help for their problems without the fear of law enforcement and it would leave the non-problematic users in peace. While there certainly are many ways to go about the problem of drug abuse and the negative effects associated with it, prohibition is simply ineffective at reducing both and will continue to harm millions of people until society finally realizes the error of their ways. Citations About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDCMinusSASstats. 3 Sept. 2020, cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html. “Against Drug Prohibition.” American Civil Liberties Union, aclu.org/other/against-drug-prohibition#:~:text=Drug%20Prohibition%20Creates%20More%20Problems%20Than%20It%20Solves,other%20serious%20social%20problems.%20Caught%20in%20the%20crossfire. Biedermann, Nils. How Prohibition Makes Drugs More Potent and Deadly | Nils Biedermann. 9 June 2017, fee.org/articles/how-prohibition-makes-drugs-more-potent-and-deadly/. Black News and Current Events from African American Organizations, DogonVillage.Com. dogonvillage.com/african_american_news/Articles/00000901.html. Burrus, Trevor. “The Hidden Costs of Drug Prohibition.” Cato Institute, 19 Mar. 2019, cato.org/publications/commentary/hidden-costs-drug-prohibition. Coyne, Christopher J., and Abigail R. Hall. “Four Decades and Counting: The Continued Failure of the War on Drugs.” Cato Institute, 22 Sept. 2020, cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/four-decades-counting-continued-failure-war-drugs. Dai, Serena. “A Chart That Says the War on Drugs Isn’t Working.” The Atlantic, 30 Oct. 2013, theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/10/chart-says-war-drugs-isnt-working/322592/. “Drug War Statistics.” Drug Policy Alliance, 2 Dec. 2020, drugpolicy.org/issues/drug-war-statistics. Elflein, John. “Deaths by Drug Overdose U.S. 1950-2017 | Statista.” Statista, 6 Nov. 2019, statista.com/statistics/184603/deaths-by-unintentional-poisoning-in-the-us-since-1950/. “End the War on Drugs.” American Civil Liberties Union, 9 July 2018, aclu.org/issues/smart-justice/sentencing-reform/end-war-drugs. Goldstein, Diane. “The Mischaracterized Relationship Between Drug Use and Homelessness.” Filter, 22 May 2020, filtermag.org/drugs-homelessness/. Hari, Johann. Chasing the Scream. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2015. “Housing First - National Alliance to End Homelessness.” National Alliance to End Homelessness, 24 Aug. 2020, endhomelessness.org/resource/housing-first/. John Ehrlichman - Wikipedia. 26 Nov. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ehrlichman#:~:text=Drug%20war%20quote,-In%202016%2C%20a&text=You%20understand%20what%20I’m,we%20could%20disrupt%20those%20communities. Lopez, German. “How America Became the World’s Leader in Incarceration, in 22 Maps and Charts.” Vox, 11 Oct. 2016, vox.com/2015/7/13/8913297/mass-incarceration-maps-charts. Pearl, Betsy. “Ending the War on Drugs: By the Numbers - Center for American Progress.” Center for American Progress, 27 June 2018, americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2018/06/27/452819/ending-war-drugs-numbers/#:~:text=Economic%20impact,more%20than%20%243.3%20billion%20annually. “Ending the War on Drugs: By the Numbers - Center for American Progress.” Center for American Progress, 27 June 2018, americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2018/06/27/452819/ending-war-drugs-numbers/. “Race and the Drug War.” Drug Policy Alliance, 23 Sept. 2020, drugpolicy.org/issues/race-and-drug-war. Rates of Drug Use and Sales, by Race; Rates of Drug Related Criminal Justice Measures, by Race | The Hamilton Project. 8 Oct. 2020, hamiltonproject.org/charts/rates_of_drug_use_and_sales_by_race_rates_of_drug_related_criminal_justice. Roberts, TJ. “Iron Law of Prohibition: The Case Against All Drug Laws.” The Advocates for Self-Government, 29 Oct. 2019, theadvocates.org/2019/05/iron-law-of-prohibition-the-case-against-all-drug-laws/. Staffing and BudgetLock. dea.gov/staffing-and-budget. Szalavitz, Maia. “Street Opioids Are Getting Deadlier. Overseeing Drug Use Can Reduce Deaths | Maia Szalavitz.” The Guardian, 3 June 2016, theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/apr/26/street-opioids-use-deaths-perscription-drugs-fentanyl. “The State of Opioids.” Vera, 2 Dec. 2020, vera.org/state-of-justice-reform/2017/the-state-of-opioids. Thornton, Mark. “Alcohol Prohibition Was a Failure.” Cato Institute, 22 Sept. 2020, cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/alcohol-prohibition-was-failure. About the Author:

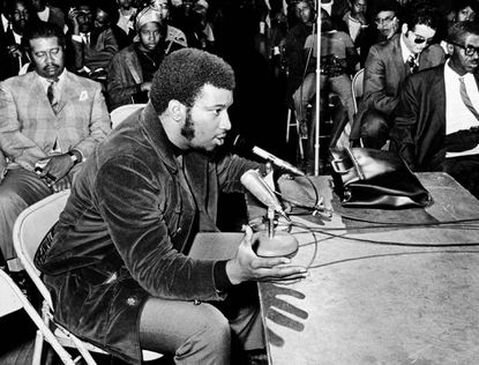

I am N.C. Cai. I am a Chinese American Marxist Feminist. I am interested in socialist feminism, Western imperialism, history, and domestic policy, specifically in regards to drug laws, reproductive justice, and healthcare. It is generally accepted by most on the ‘left’ that capitalism required the black slave for capital to be “kick-started”,[1] and consequently, that the similarities in the lives of the early black slave and the white indentured servant required the creation of racial differentiation (hierarchical and racist in nature) to prevent Bacon’s Rebellion style class solidarity across racial lines from reoccurring. The capitalist class in the US has been historically successful in creating an atmosphere within the circles of radical labor that excludes solidarity with black liberation and feminist struggles. Yet, the black community historically has been at the forefront of the struggle for socialism in the US. Taking into consideration the history of dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, radical labor in the US has had towards black struggles for liberation, how could it be that the black community has stood in a vanguard position in the struggle for an emancipation that would include those whom they have been excluded by? This paper will look at two occasions in which we can see the exclusion of identity struggles from labor struggles, and answer the riddle of how white labor has been able to identify more with capitalist of their own race than with their fellow nonwhite worker. In connection to this, we will be examining three different perspectives concerning the relationship of the black community’s receptivity and active role in the struggle for socialism and the emancipation of labor. A perfect example of this previously mentioned exclusion of identity from labor can be seen in Jacksonian radical democrats like Orestes Brownson, who although representing a radical emancipatory thought in relation to labor, failed to see how the abolitionist movement should have been included into the cause of the northern workers. Thus, his positions was (before falling into conservatism), that “we can legitimate our own right to freedom only by arguments which prove also the negro’s right to be free”.[2] The question is the negro’s right to be free when? Although he included blacks into the general emancipatory process, he was staunchly against abolitionist as “impractical and out of step with the times”,[3] and eventually urged northern labor to side with the southern plantation owners to counter the force of the northern industrial capitalist. What we see here with Brownson is a dismissal for the abolitionist struggle against black chattel slavery, unless it takes a secondary role to white labor’s struggle for the abolition of wage slavery. Brownson’s central flaw here is his assumption that you can free one while maintaining the other in chains, whereas the reality is that “labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded”[4] In the generation of American radicals that came after Brownson we see a similar dynamic between the 48’ers[5] of the first section of the International and the utopian/feminist radicals of sections nine and twelve. This split takes place between Sorge and the German Marxist and the followers of the ‘radical’ Stephen Andrews and the spiritualist free-love feminist Victoria Woodhull. As Herreshoff states, in relation to the feminist movement of the time, “the Marxists were talking to the feminist the way Brownson had talked to the abolitionist before the Civil War.”[6] By this what is meant is that the struggle for women’s political emancipation, was treated as a sideline issue, that should be dealt with – or automatically solved – only after labor’s emancipation. Now, it could very well be argued that the positions taken by Sorge and some of the other Marxist 48’ers was not ‘Marxist’ at all. Marx and Engels were staunch abolitionist, close followers (and writers) of the Civil War, and even pressured Lincoln greatly towards taking up the cause of emancipation; this puts them in a direct opposition to the positions taken by the northern labor radicals like Brownson[7]. Engels also pronounced himself fully in favor of women’s suffrage as essential in the struggle for socialism[8]. The expansion of this argument cannot be taken up here though. The point is that racial and sexual contradictions within the working masses have played an essential function in maintaining the capitalist structures of power. While workers identify – or are coerced into identifying – workers of other races, ethnicities, or sexes as their enemy, their real enemy – their boss – is either ignored or positively identified with. Thus, white workers can blame their wage cuts/stagnations on the undocumented immigrant. Although he does play a function in maintaining wages low, the one who sets the terms for the function the immigrant is coerced into playing is the capitalist, not the immigrant. There are countless analogies to describe this relation, my favorite perhaps is the one of the cookies. In a table you have 100 cookies, on one side of the table you have the capitalist (usually caricatured as a heavy-set fellow) with 99 cookies to eat for himself. On the other side you have a dirtied white face worker, a dirtied brown face immigrant worker, and finally, the last cookie. The capitalist leans to the white worker and tells him, “be careful, the immigrant will take your cookie”. Here we have the general function of racial division, the motto which is “have the white worker base his identification not in the dirt on his face, but in the mythical face laying under the dirt”. This mythical face under the dirt is the symbolic link of the white worker and the white capitalist. The link of commonality is based on the illusion of the undirtied faced white worker. The dirt, of course, symbolizes the everyday conditions of his toiling existence. Even though the white worker’s everydayness is infinitely more like the immigrant’s (immigrant here is replaceable with black/women/etc.), he is coerced into consenting his identification with whom he has in common no more than one does with a bloodsucking mosquito on a hot summer’s day. Regardless of the dismissal, and sometimes even hostility, of radical labor’s relation to other identity struggles, the black community has been in the forefront of the struggle for socialism in America. Not only have elements of the black community consistently served as the revolutionary vanguard, but the community itself has historically expressed a receptivity of socialism that is unmatched by their white working-class counterparts. There have been a few interesting ways of explaining the phenomenon of the black community’s receptivity of socialist ideas. Edward Wilmont Blyden, sometimes called the father of Pan-Africanism, argued in his text African Life and Customs that the African community is historically communistic. Thus, there is something communistic within the ethos of the black community, that even though it has been generationally separated from its origins, maintains itself in the black experience. He states that the African community produced to satisfy the “needs of life”, held the “land and the water [as] accessible to all. Nobody is in want of either, for work, for food, or for clothing.” The African community had a “communistic or cooperative” social life, where “all work for each, and each work for all.”[9] The argument that a community’s spirit or ethos plays an essential role in its ability to be receptive to socialism is one that is also being analyzed with respect to the “primitive communism” of indigenous communities in South America. Most famously this is seen in Mariategui, who states: “In Indian villages where families are grouped together that have lost the bonds of their ancestral heritage and community work, hardy and stubborn habits of cooperation and solidarity still survive that are the empirical expression of a communist spirit. The “community” is the instrument of this spirit. When expropriations and redistribution seem about to liquidate the “community,” indigenous socialism always finds a way to reject, resist, or evade this incursion.”[10] These arguments have been recently found by Latin American Marxist scholars like Néstor Kohan, Álvaro Garcia Linera, and Enrique Dussel, to have already been present in Marx. From the readings of Marx’s annotations of the anthropological texts of his time (specifically Kovalevsky’s), they argue that Marx began to see the revolutionary potential of the “communards” in their communistic sprit. This was a spirit that staunchly rejected capitalist individualism, leading him to believe that its clash with the expansive nature of capital, if victorious, could be an even quicker path to socialism than a proletarian revolution. Not only would the indigenous community serve as an ally of the proletariat as revolutionary agent, but the communistic spirited community is itself a revolutionary agent too.[11][12] Another way of explaining the phenomenon of a historically white radical labor movement (at least until the founding of CPUSA in 1919), and a historically radical black community[13], is through reference to an interview Angela Davis does from prison when asked a similar question. In this 1972 interview Angela mentions that the black community does not have the “hang ups” the majority of the white community has when they hear the word ‘communism’. She goes on to describe an encounter with a black man who tells her that although he does not know what communism is, “there must be something good about it because otherwise the man wouldn’t be coming down on you so hard.”[14] What we have here is a sort of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. The acceptance of communism is because of the militant rejection my oppressor has towards it. Although it might seem as a ‘simplistic’ conclusion, I assure there is a profound rationality behind it. The rationality is this “if the alternative is not different enough to scare my oppressors shitless, it is not an alternative where my conditions as oppressed will change much.” This logic, simplistic as it might seem, is one the current ‘socialist’ movement in the US is in dire need of re-examining. If the alternatives one is proposing does not bring fright upon those whose heels your necks are under, then what one is proposing is no qualitative alternative at all; rather, it is merely a request to play within the parameters the ruling class gives you. The relationship of who is setting the parameters is not changed by the mere expansion of them. Both of these ways of examining the question concerning the relationship of the black community and its acceptance of socialist ideas I believe hold quite a bit of truth to them. Regardless, I think there is one more way to answer this question. The difference is that in this new way of answering the question, we are threatened with finding the possibility of the question itself being antiquated. The thesis I think is worth examining relates to this previous “mythical link” the white worker can establish with the white capitalist. Unlike the white worker, the black worker has not – at least historically – had the ability to identify with a black capitalist from the reflective position of his ‘undirtied’ face. This is given to the fact that the capitalist class, or even broader, the class of elites or the top 1%, has been almost homogeneously white. Thus, whereas the white worker could be manipulated into identifying with the white capitalist, the white homogeneity of the capitalist class did not have the ripe conditions for working class black folks to be manipulated in the same manner. The question we must ask ourselves now is: in a world of a socially ‘progressive’ bourgeois class, like the one we have today, can this ‘mythic-link’ come into a position of possibly becoming a possibility? With the efforts of racial (and sexual) diversification of the top 1%, can this change the relationship of the black community to radical politics? If we accept the thesis that the link of the black community to radical politics has been a result of not being able to – unlike the white worker – have any identity commonality with their exploiter, then, can we say that in a world of a diversified bourgeois class, the radical ethos of the black community is under threat? Is the black working mass and poor going to fall susceptible to the identity loophole capitalism creates for coercing workers into consenting against their own interest? Or will its historical radical ethos be able to challenge it, and see the black bourgeois as much of an enemy as the white bourgeois? Under a diversified bourgeois class, will Booker T. Washington style black capitalism become hegemonic in the black community? Or will the spirit still be that of Fred Hampton’s famous dictum from his Political Prisoner speech “You don’t fight fire with fire. You fight fire with water. We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity. We’re not gonna fight capitalism with black capitalism We’re gonna fight capitalism with socialism.”? I am unsure, but I think perhaps a totally disjunction-al way of thinking about it is incorrect; as in, the disjunction will not be one the totality of the community is forced to homogeneously choose, but one which fractures the community itself without leaving any side’s perspective hegemonized. Regardless, I think it is up to those who represent the cause of the white and non-white working mass and poor, to go these spaces and assure that masses begin to identify based on class lines (‘class’ not restrictive to the industrial proletariat, but expanded to the totality of the working masses, and beyond that to the lumpen elements whose systemic exclusion, excludes them as well from being exploited subjects of the system). Only in this ‘class’ identity approach can we achieve the unity necessary to solve not just the antagonisms of class that capitalism develops and continuously exacerbates, but also those of race, sex, and climate. This does not mean, like it meant for the 19th century labor radicals, that we exclude non-class struggles to a peripherical position where we give them importance only after the socialist revolution has triumphed. Rather, our commonality of interests in transcending the present society forces us to examine how we can work together, and in doing so, begin to acknowledge and work on the overcoming of our own contradictions with each other. Citations. [1]III, F. B. (2003). The Prison Slave as Hegemony's (Silent) Scandel. In Afro-Pessimism An Introduction (pp. 72). [2] Brownson, O. A. “Slavery-Abolitionism.” Boston Quarterly Review, I (1838), (pp. 240). [3] Herreshoff, D. American Disciples of Marx (Wayne State University Press, 1967), (pp. 39). [4] Marx, K. (1967). Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production (Vol. 1). (F. Engels, Ed.) International Publishers. (pp. 301) [5] “48’ers” refers to the Germans that came after the attempted revolution of 1848 (the one the Communist Manifesto was written for). Having to face persecution, many fled to the US. [6] Ibid. (pp. 82). [7] For more see: Marx, K. & Engels, F. The Civil War in the United States (International Publishers, 2016) [8] For more see: Engels, F. The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (International Publishers, 1975) [9] Blyden, E. W. African Life and Customs (Black Classic Press, 1994) (pp. 10-11) [10] Mariategui, J. C. Seven Essays of Interpretation of Peruvian Reality (1928), (pp. 68) [11] Linera, A. G. (2015) Cuaderno Kovalevsky. In Karl Marx: Escritos Sobre la Comunidad Ancestral [12] This is itself a message that strikes at the heart of the dogmatism of certain Marxist circles. Circles that religiously follow the early unilateral theory of history Marx’s begins proposing in The German Ideology, a view that was used to argue the revolutionary futility of these communities, and the need to ‘proletarianize’ them. This does not mean we throw out Marx’s discovery of the materialist theory of history upon which the unilateral theory of history arises; but rather, that we treat it in a truly materialist manner (as the later Marx does) and realize the ‘five steps’ to communism is materially specific to the studies Marx had done with relation to the European context. With relation to other contexts, new studies must be made through the same materialist methodology. [13] This is not to be taken as a statement of the homogenous radicalism of the black community in America. The influence of Booker T Washington style of black capitalist ideology does historically have a certain influence in the black community. But, when considered in proportion to the white population, the acceptance of socialism – and its vanguard role in struggles – has been much greater in the black community. [14] Marxist, Afro. (2017, June 11) Angela Davis - Why I am a Communist (1972 Interview) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGQCzP-dBvg About the Author:

My name is Carlos and I am a Cuban-American Marxist. I graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Loras College and am currently a graduate student and Teachers Assistant in Philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. My area of specialization is Marxist Philosophy. My current research interest is in the history of American radical thought, and examining how philosophy can play a revolutionary role . I also run the philosophy YouTube channel Tu Esquina Filosofica and organized for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. As David Walker conveys throughout his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, African American people have historically been treated in such a manner that arguably makes them the most oppressed group of people in recent history (Walker and Hinks 2000, 6-7). In regards to environmental conditions, African Americans have historically been discriminated against in the same way, both directly and indirectly (Williams 2018, 253-255). Environmental injustice towards minorities is a common feature of many American cities today and this is not only a recent phenomenon; as the Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty (2008) report suggests, race and environment seem to be inextricably linked in most American cities, as areas that were mostly black “suffer from greater environmental risks than the larger society”. (Bullard et al 2008, 377) Throughout my research, I attempted to find the cause of this discrimination that negatively influences the lives of many African Americans today. I specifically looked through documentation of segregation throughout American history to answer the question of the extent segregation, both in its de facto and de jure forms, plays a role in shaping the environmental injustices associated with environmental racism in the United States today. For context, de jure segregation refers to “the legalized segregation of Black and White people” while de facto segregation refers to the form of segregation rooted in “common understanding and personal choice” (Edupedia 2018). Thus, throughout my investigation, I aimed to determine how both of these forms of historical segregation have caused the environmental injustices that face African American people today. Through my analysis, I have concluded that both de facto and de jure segregation have had an immense influence on the difference in environmental conditions in locations where most African American people reside as opposed to communities where most white people live. De jure segregation was a common feature in the South following Reconstruction. Its implications on the region and its people are vast (Oldfield 2004, 71-91). Its roots in Southern politics were established in the Reconstruction period, culminating with the Supreme Court decision that legally permitted segregation in the form of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which declared that “separate but equal” public spaces were legal under the Constitution (Supreme Court of the United States 1896). Plessy v Ferguson was essential in causing the conditions that have brought upon the environmental oppression in the South. By legally allowing for the racialization of geographical distribution, (by declaring “separate but equal” as constitutional) the federal government allowed for whites in the South to create geographies that were to their advantage (as in, whites used their power to move to nicer communities and to pass laws that kept minority groups in less desirable areas) (Hoelscher 2003, 671). By harnessing the power to create their own geographies and to influence the demographic makeup of a given area or neighborhood during the era of Jim Crow, the whites in the South were effectively able to choose to reside in communities that were cleaner and nicer, which could be seen as a direct cause of the environmental racism that plagues the nation today. Through their report on the demographic variation in high and low-lying communities in the South, Ueland and Warf concentrate on the racialization of topography (the differences in altitude between communities that were mostly white and communities that were mostly black) in the region. They conclude that, in a majority of Southern cities, African Americans tended to reside in lower-lying communities, which were more prone to environmental hazards and health risks (Ueland and Warf 2006, 50-73). Through the decision that Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) established, segregation was a legal phenomenon for many years and, because of this, whites in the South were able to continue to oppress black people through the usage of geography. I believe that, as a direct result of the segregation that the 1896 decision yielded, environmental racism was produced. Had it not been for the legality of the policy “separate but equal,” whites in the South would not have been as easily able to have the power to create geographies and communities that segregated themselves off from black people. Through Ueland and Warf’s report on the geographical causes of environmental racism in the South, it is plausible to argue that de jure segregation in the Jim Crow South does indeed still have implications in furthering environmental racism as the altitudinal difference between black communities and white communities, which was, at least in part, due to the legality of segregation established by Plessy v. Ferguson. Therefore, de jure segregation in the South stemming from policies established by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) (as well as a multitude of other laws passed in the Jim Crow South) has a great influence on modern-day environmental racism as it allowed for the creation of geographies that favored white people and pushed minorities into communities that were more environmentally hazardous. By the same token, segregation that was enabled through the creation of urban infrastructure, the suburbanization of the white community, and other forms of de facto segregation that have caused the environmental inequalities that shape many American cities today. To begin, in Los Angeles, African Americans reside in districts that have disproportionately more environmental hazards, which “is largely a function of severe spatial containment and the historic practice of locating hazardous land uses in black areas” (Paulido 2017, 31). Despite not being a part of the Jim Crow South, Los Angeles still exhibits similar racial injustices environmentally as the segregated Southern cities, thus supporting the notion that environmental racism is not solely a product of de jure segregation. Since Los Angeles’ environmental racism, according to Pulido, stems from segregation based on de facto strategies employed by whites to empower themselves through advantageous geographies (for example, Pulido cites white communities in LA making harsh zoning laws to keep minorities out), one can plausibly argue that de facto segregation could play a crucial role in the racist environmental landscapes of the modern-day United States (Pulido 2017, 31). One may critique this argument by pointing out its inability to be generalized to most American cities. However, this trend of de facto mannerisms of the mid and late 1900s contributing to modern-day environmental racism can be seen through analyzing the impact of these mannerisms on the landscapes of other modern U.S. cities. For example, freeways in the Chicago area have adversely impacted African Americans there. As claimed by Rashad Shabazz, “the mammoth Dan Ryan Expressway, which, after its opening in 1967, cut off access to Bridgeport, the working/middle-class, white, and resource-rich community…” which resulted in a wide range of consequences for Chicago’s black population (Shabazz 2017, 64). The construction of the I-90/I-94 freeway complex through Southern Chicago directly resulted in environmental consequences that unjustly affect African Americans as it spatially contained Chicago’s black population to the so-called “Black Belt,” which was “roughly a seven-mile-long by one-mile-wide strip of land” (Shabazz 2017, 40). As Illinois’ Better Government Association cites, the South Side neighborhoods of Chicago (that were cut off from white neighborhoods by the construction of freeways like the Dan Ryan) are some of the most polluted and unhealthy environments in the city’s metro area (Chase and Judge 2019). Thus, the construction of freeways in Chicago, which spatially restricted black communities from access to neighboring white communities, could be seen as a cause of the unequal environmental geography in the city. Furthermore, the Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty report also states that, “Six metropolitan areas account for half of all people of color living in close proximity to all of the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities: Los Angeles, New York, Detroit, Chicago, Oakland, and Orange County, CA” (Bullard et al 2008, 405). As the report suggests, Northern (and Western) cities are hubs for racist environmental injustices. As segregation was not legally enforced in the North to the extent that it was in the Jim Crow South, it would be incorrect to suggest that only segregation upheld by law has historical roots in environmental racism as the biggest oppressors (in regards to hazardous waste facilities) are, in fact, Northern cities. Therefore, as seen through examples such as the freeway planning in Chicago and suburbanization in Los Angeles, de facto segregation is a prevalent theme in urban neighborhoods across the country; de facto segregation in Northern and Western urban hubs has directly sparked environmental injustices that can be observed today. Similar to the de facto segregation established through suburbanization, infrastructural projects, and other urban projects that spatially contained minorities, segregation that was not institutionalized (de facto) in the business realm (both through nonprofit lobbyists and through specific privatized industries) also could be traced to as a potential cause of racism through environmental inequality. To commence, in the 1970s and 1980s, environmental non-profit organizations in Southern Arizona directly influenced the variance in environmental conditions based on racialized geographies, as they raised funds and made efforts to make white districts of Tucson and other cities cleaner and more sustainable, while leaving minority communities behind (Clarke and Gerlak 1998, 862). Through the usage of governmental and business power (despite being non-profits), white environmental organizations were able to fund projects that would be most advantageous to their communities, leaving Hispanic and African American communities in more environmentally hazardous zones. Thus, de facto segregation spurred through the agenda of non-profit organizations led by white people could be seen as a key cause in the disparity in environments between white and black communities in cities like Tucson. To further this, rural environments are also scenes of environmental subjection today. In the South, pesticides that were toxic and linked to certain diseases played a key component in the efficiency of agriculture in the region, thus giving whites in power, like Jamie Whitten (a U.S. representative, white supremacist and advocate for the pesticides industry despite its racist attributions) the incentive to use the pesticides on a wide scale, even if this caused health consequences for laborers in the region, who were generally black (Williams 2018, 243-258). Williams analyzes historical accounts of doctors and medical professionals in the Mississippi Delta region and concludes that African Americans were clearly adversely influenced (in regards to health) by the introduction of pesticides to Southern agriculture, therefore, representing that business ventures also produced environmental racism (Williams 2018, 243-258). As exemplified by Williams’ case study on the impact that the pesticide industry’s power in the South has had on African Americans in the region, business practices and agendas have also played a role in the development of environmental racism. Businesses and industries, like the pesticides industry, that were funded and are still funded by rich white people to the expense of the well-being of black people, could be seen as agents of environmental racism in many cases; given that the policies they advocate for, in desire for maximized profits and white power, are harmful to African Americans’ health and sense of well-being. Therefore, there are several contributions that non-profit organizations and businesses/industries run by whites in power have made that have directly caused environmental injustice, in the form of health risks and hazards that disproportionately affect the black community. These contributions took the forms of advancements for white communities as well as the creation of obstacles to the African American community’s success and overall well-being. Thus, de jure and de facto segregation prevalent in the Jim Crow South and urban North in the early and mid 1900s, as well as the de jure and de facto segregation established through business practices and urban plight in the late 1900s have all played a crucial role in developing the environmental injustices that face the African American community today. As seen through the interconnections between controversial expressways in Chicago (Shabazz 2017, 64), to the disproportionate representation of black people at low-lying (unfavorable) topographies in Southern cities (Ueland and Warf 2006, 50-73), to the environmental hazards plaguing black people in urban neighborhoods in the West and North (Bullard et al 2008, 405) to the not-so “color blind” (Jaime Whitten hypocritically said he advocated for “color blind” politics when clearly his policies directly caused African American people to get sick) politics of the pesticide industry and its place in Southern agriculture (Williams 2018, 243-59). Environmental racism in its current form can be traced back to historical forms of segregation, whether legally mandated or not, that produced the geographies and conditions that are associated with modern-day environmental racism. Therefore, both twentieth century de jure and de facto segregation play a vital role in shaping modern-day racialized environmental injustice. Citations

About the Author:

My name is Logan Cimino. I am a second year student at the University of California Santa Barbara studying economics and geography. I am an aspiring urban planner and I hope to introduce more left-wing policies to planning in order to make cities more sustainable and equitable. I am particularly interested in advocating for solutions to residential segregation and environmental racism. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed