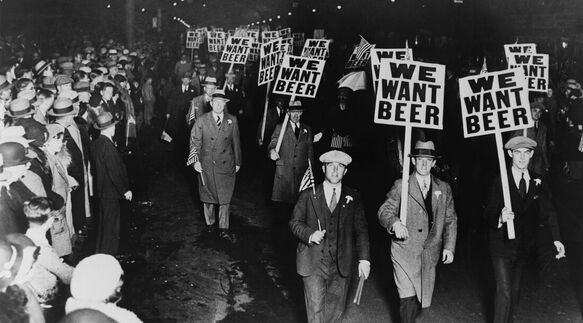

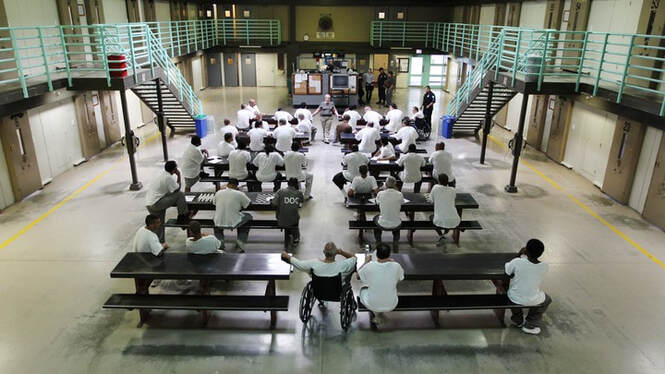

IntroductionIn US history the two largest spikes in the murder rate have happened during eras of drug prohibition. The first spike occurred from 1920 to 1933 during the prohibition of alcohol. The second from 1970-1990 when Nixon declared the war on drugs. From the very start, the war on drugs has been about suppressing the poor and the marginalized. And, even if it was about eliminating drug use and all the horrible issues related to it, such as addiction, mental health disease, poverty, and violence, it has proven a failure in stopping those as well. Instead, the war on drugs has worsened these problems causing more chaos, pain, addiction, and death. The war on drugs and drug prohibition as a whole has been completely ineffective at reaching its goals of eliminating drug use and the negative effects associated with it. HistoryAs ingrained as drug laws seem today, it was only in 1875 when San Francisco passed the nation’s first anti-drug law. The law wanted to stop the spread of opium dens and banned the practice of smoking opium. A federal law accompanied the San Francisco law, banning anyone of “Chinese origin” to bring opium into the country. The racist excuses didn’t end, the targeting of cocaine followed suit in 1909 when rumors began to spread that black men were getting high on cocaine and as a result were raping white women. These rumors allowed a mass hysteria to sweep the nation and anti-cocaine laws followed suit. Five years later in 1914, the Harrison Narcotics Act passed. While the HNA didn’t outright ban drugs such as cocaine, cannabis, and heroin, it expanded the government's ability to tax and regulate them. The goal being to tax drugs to the point of nonexistence. However, despite the HNA, cannabis still remained popular especially among the jazz and swing scene in the 1920s and 30s. At this point, Harry Anslinger, head of the Bureau of Narcotics and notorious for being racist even in the 1930s steps in. Anslinger warned the nation that jazz and marijuana created an opportunity for blacks to rise above the rest; and that it induced madness in Hispanic immigrants leading them to commit violence against whites. Then in 1937, Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act for the purposes of raising the prices of marijuana making it even more inaccessible. The same trends of reactionary backlash are shown in the 1960s and 1970s, amidst a variety of social movements but mainly the civil rights, and anti-war movement. These movements caused the rightwing who were unwilling to acquiesce to any of the demands to crack down on drugs which they knew would harm those communities. John Erlichman an assistant to the Nixon administration, even admitted in 2016 in an article by Dan Baum for Harper’s Magazine that racism and suppression of opposition to the Nixon administration was the reason why they further agitated the war on drugs. Stating, “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities…. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.” From the very beginning, drug prohibition existed to suppress a society’s underclass. While there are numerous supporters with good intentions the unpleasant roots do not simply disappear. Thus, supporting prohibition ignores the history of ruthless attacks against minorities and contradicts America’s values such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Economics: The Iron Law of ProhibitionRacist origins and intentions aside, even if the war on drugs started out by attempting to lower drug use and by extension to create a healthier society, it still would have resulted in a massive disaster. Simply banning drugs doesn’t stop people from using them. The perfect example of this is alcohol prohibition. While it is true that alcohol consumption dropped significantly in 1921 from about 0.8 gallons to 0.2 gallons, the rate sharply rose in 1922 to 0.8 gallons and continued on an increasing trend through the 1920s. Prohibition failed at lowering alcohol consumption for most of its duration and made the alcohol more potent. This is due to the Iron Law of Prohibition by Richard Cohen which states that the stricter the law enforcement, the more potent a substance becomes. Prior to prohibition Americans spent a falling share of their income on alcohol and purchased higher quality and weaker drinks. They also spent similar amounts of money on both beer and spirits. However, after Prohibition spirits replaced beer as the drink of choice for almost all consumption and production of alcohol. Hard liquor and spirits are more potent than beer and wine which made it easier to hide and transport. Liquor and spirits could also be sold to greater amounts of people. The largest cost in selling an illegal good is avoiding detection by the authorities. Weaker products like beer were too bulky and indiscrete. As a result of the law, the prices of beer rose more drastically than that of brandy and spirits (700, 433, and 270 percent respectively). Beer consumption and production all but disappeared with the exception of homemade beers. However, after prohibition was repealed total expenditure on distilled spirits as a percentage of total alcohol sales severely dropped and people returned to drinking beer and other milder forms of alcohol. The lesson gleaned from this experiment gone wrong is that prohibition is completely ineffective at reducing drug abuse and addiction. Prohibition is completely counterintuitive because rather than stopping people from using drugs it makes drugs more potent and more addictive which increases drug use. Black markets are like all markets, the profit motive is king, which means drug dealers want the biggest bang for their buck. Especially when the largest cost of buying and selling drugs on the black market are the social and legal consequences. In order to get the best deal, drug dealers must satisfy the demand of as many consumers and create new ones without getting caught. This means that they have a financial incentive to increase the potency of the drugs because stronger drugs are easier to hide and transport thus lowering the social and legal risks. Along with lowering the costs, more potent drugs are able to meet the demand of more consumers than weaker drugs. Take the example of alcohol, while a gallon of beer can only be sold to two people, a gallon of spirits can be sold to ten people. The seller makes more money selling spirits to ten people than only selling beer to two people. In the situation of transporting the drugs since beer is bulkier and satisfies less demand, there is more of a legal and social incentive to produce and distribute spirits. However, the Iron Law of Prohibition doesn’t only apply to distributors it also applies to the consumer. Take the example of a college football game, stadiums typically ban alcohol, as a result, college students who are typically beer drinkers now become hard-liquor drinkers. Since it's easier to sneak in liquor in a flask than it is beer bottles which are heavier and less discrete. While there certainly is a problem with drinking and alcoholism in the US, prohibition is simply not the solution. Drug Prohibition forces drug use and distribution to occur under a black market which creates more addictive and potent drugs. The results of Prohibition merely exacerbate the overdose crisis and line the pockets of drug lords. Expense of the War on DrugsThe War on Drugs is perhaps one of the largest scams in US history. According to the Center for American Progress, the federal government has spent an estimated 1 trillion dollars on the war on drugs, increasing every day since the 1970s. From 2015 the government has spent more than 9.2 million dollars every day to incarcerate people with drug offenses alone. The federal government isn’t the only party that spends outlandish amounts of money on drug enforcement. In 2015 alone states spent about 7 billion dollars on incarcerating people on drug-related charges. Georgia spent about 78.6 million dollars just to incarcerate people of color on drug charges, an amount that is 1.6 times more than the amount it spent on treatment services for drug use. However, enforcement isn’t the only cost, what happens once the person convicted of drug charges gets released? Their employment and economic prospects are ruined. For example, the Cato Institute estimated that the cost of the diminished employment aspects of felons ranges from about 78-87 billion dollars. In total the war on drugs costs the US about 51 billion dollars annually. That is 51 billion dollars every year for a crusade that has done nothing but destroy the lives of millions, rob Americans of their freedom, and create countless unproductive members of society. Bear in mind that there are many better alternatives to using 51 billion dollars for a racist witch hunt, a great alternative would be ending homelessness which would only cost about 20 billion dollars. Having access to a shelter would make it easier for people to get a job since most job applications require an address. Having a home would also encourage people to live in a stable supportive community where there would be support for them to go to rehab. In an era with greater wealth inequality and a growing deficit, hunting people down for doing what they want with their bodies should be the last thing on the mind of the state. Especially a state that is well known for committing horrible atrocities to minorities and reinforcing institutions such as Jim Crow and slavery which continue to leave a lasting scar on millions of people. Crime and PunishmentAside from taking away the right of every American the liberty to do whatever they want with their body, the war on drugs also punishes thousands if not millions by locking them up in a cage if even caught with a single trace of a drug, even something as innocuous as weed. In 2018 the U.S arrested more than 1.6 million people for drug-related charges, of those arrested more than 1.4 million were for possession only, and of those arrested for possession about 608,000 of them were for marijuana possession. However, the penalties are almost never distributed evenly, despite making up only about 13% of America’s population, blacks make up about 27% of drug arrests. Nearly 80% of people arrested for drug-related charges in federal prisons and 60% in state prisons are black or Latino. Prosecutors were also more likely to pursue mandatory minimum sentences for blacks than whites. In 2011 of those who received a mandatory minimum, 38% were black and 31% were Latino. However, despite unequal enforcement blacks and whites use and sell drugs at similar rates yet black people face harsher punishments if caught using drugs. The war on drugs is nothing more than an excuse to deny America’s problem with systemic bigotry. Rather than solving the problems arising from systemic racism, the war on drugs associated minority communities with drugs and poor behavior instead of actually solving these problems at their root cause. EffectivenessHowever, has locking up people for drug offenses actually reduced drug use and crime? The answer is no, drug overdoses have skyrocketed since the 1980s. The drug abuse rate has remained stagnant since the 1970s at 1.3 percent despite US spending on drug control significantly increasing since the 70s. The Center for American Progress adds that incarceration has shown to have had a negligible impact on drug abuse rates and in fact are linked with higher rates of overdose and mortality. Prisoners in the first two weeks upon release faced a mortality rate that was 13 times higher than the general population. The leading cause of death among these people is overdose. Incarceration is a traumatic experience for most people. In prison, violence is a constant presence by both inmates and guards. Many also face solitary confinement, a punishment so torturous that it’s been called out by the UN and has been proven to induce a variety of mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, psychosis, self-harm, and suicide. Upon release, all opportunities for decent employment are nonexistent, as are paths to being able to enroll in higher education, and not being able to live in public housing or to be able to buy a home. All of these factors create the perfect conditions for addiction and drug use. Contrary to popular opinion the substance itself only plays about a 20% role in addiction. The Office of the Surgeon General found that only 17.7% of nicotine patch wearers stopped smoking. While 20% is still significant it nonetheless shows that chemical hooks aren’t the overwhelming reason why people are addicted and that there are greater causes of addiction outside pharmacology. In regards, of the 80% gap the psychological state of the user is perhaps more influential than the chemical hooks. According to a study conducted by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente called the “Adverse Childhood Experiences Study” the scientists looked at ten different traumatic events that could happen to a child such as physical and sexual abuse to the death of a parent. Discovering that for each traumatic event the child’s chances of becoming an addicted adult increased 2-4 fold. They also found that nearly two-thirds of injection drug use was the result of childhood trauma. Addiction isn’t the result of bad morals it’s the result of pain. Of course, people with pain will try to numb it whether it's as simple as taking an aspirin for a headache, drinking after work after a rough day, or injecting heroin to forget about a traumatic event. The only difference is that society condones the first two while tossing the third one in jail. By criminalizing people with substance abuse disorders society is criminalizing mental illness rather than treating it. Therefore, when society throws these people who already deal with unbearable amounts of pain and which resort to self-medication with illicit drugs, they are not getting rid of the problem, they are aggregating it by creating more suffering for the person who is already in pain. ConclusionThe War on Drugs has been a disaster of epic proportions from locking up millions of people and ostracizing drug users, to stripping Americans of their liberty to do as they please with their body. The War on Drugs dehumanizes drug addicts who most likely faced some sort of traumatic event in their life and further exacerbates the problem by adding more trauma via incarceration and the denial of support upon release. All of this added pain makes the susceptible person more likely to self-medicate. Since safe versions of the drugs are gone because of prohibition they have to rely on shady dealers peddling products with questionable quality and deadly potency as a result of the Iron Law of Prohibition. And if they get caught with the substance, they’re thrown into prison which creates a downward spiral. Prohibition regards drug users as below human and only worthy of contempt. It is only care and community that help people get over their problems. Thus, repealing drug prohibition would stop the stream of both non-problematic drug users and drug addicts being imprisoned. Thus, encouraging people to seek medical help for their problems without the fear of law enforcement and it would leave the non-problematic users in peace. While there certainly are many ways to go about the problem of drug abuse and the negative effects associated with it, prohibition is simply ineffective at reducing both and will continue to harm millions of people until society finally realizes the error of their ways. Citations About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDCMinusSASstats. 3 Sept. 2020, cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html. “Against Drug Prohibition.” American Civil Liberties Union, aclu.org/other/against-drug-prohibition#:~:text=Drug%20Prohibition%20Creates%20More%20Problems%20Than%20It%20Solves,other%20serious%20social%20problems.%20Caught%20in%20the%20crossfire. Biedermann, Nils. How Prohibition Makes Drugs More Potent and Deadly | Nils Biedermann. 9 June 2017, fee.org/articles/how-prohibition-makes-drugs-more-potent-and-deadly/. Black News and Current Events from African American Organizations, DogonVillage.Com. dogonvillage.com/african_american_news/Articles/00000901.html. Burrus, Trevor. “The Hidden Costs of Drug Prohibition.” Cato Institute, 19 Mar. 2019, cato.org/publications/commentary/hidden-costs-drug-prohibition. Coyne, Christopher J., and Abigail R. Hall. “Four Decades and Counting: The Continued Failure of the War on Drugs.” Cato Institute, 22 Sept. 2020, cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/four-decades-counting-continued-failure-war-drugs. Dai, Serena. “A Chart That Says the War on Drugs Isn’t Working.” The Atlantic, 30 Oct. 2013, theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/10/chart-says-war-drugs-isnt-working/322592/. “Drug War Statistics.” Drug Policy Alliance, 2 Dec. 2020, drugpolicy.org/issues/drug-war-statistics. Elflein, John. “Deaths by Drug Overdose U.S. 1950-2017 | Statista.” Statista, 6 Nov. 2019, statista.com/statistics/184603/deaths-by-unintentional-poisoning-in-the-us-since-1950/. “End the War on Drugs.” American Civil Liberties Union, 9 July 2018, aclu.org/issues/smart-justice/sentencing-reform/end-war-drugs. Goldstein, Diane. “The Mischaracterized Relationship Between Drug Use and Homelessness.” Filter, 22 May 2020, filtermag.org/drugs-homelessness/. Hari, Johann. Chasing the Scream. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2015. “Housing First - National Alliance to End Homelessness.” National Alliance to End Homelessness, 24 Aug. 2020, endhomelessness.org/resource/housing-first/. John Ehrlichman - Wikipedia. 26 Nov. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ehrlichman#:~:text=Drug%20war%20quote,-In%202016%2C%20a&text=You%20understand%20what%20I’m,we%20could%20disrupt%20those%20communities. Lopez, German. “How America Became the World’s Leader in Incarceration, in 22 Maps and Charts.” Vox, 11 Oct. 2016, vox.com/2015/7/13/8913297/mass-incarceration-maps-charts. Pearl, Betsy. “Ending the War on Drugs: By the Numbers - Center for American Progress.” Center for American Progress, 27 June 2018, americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2018/06/27/452819/ending-war-drugs-numbers/#:~:text=Economic%20impact,more%20than%20%243.3%20billion%20annually. “Ending the War on Drugs: By the Numbers - Center for American Progress.” Center for American Progress, 27 June 2018, americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2018/06/27/452819/ending-war-drugs-numbers/. “Race and the Drug War.” Drug Policy Alliance, 23 Sept. 2020, drugpolicy.org/issues/race-and-drug-war. Rates of Drug Use and Sales, by Race; Rates of Drug Related Criminal Justice Measures, by Race | The Hamilton Project. 8 Oct. 2020, hamiltonproject.org/charts/rates_of_drug_use_and_sales_by_race_rates_of_drug_related_criminal_justice. Roberts, TJ. “Iron Law of Prohibition: The Case Against All Drug Laws.” The Advocates for Self-Government, 29 Oct. 2019, theadvocates.org/2019/05/iron-law-of-prohibition-the-case-against-all-drug-laws/. Staffing and BudgetLock. dea.gov/staffing-and-budget. Szalavitz, Maia. “Street Opioids Are Getting Deadlier. Overseeing Drug Use Can Reduce Deaths | Maia Szalavitz.” The Guardian, 3 June 2016, theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/apr/26/street-opioids-use-deaths-perscription-drugs-fentanyl. “The State of Opioids.” Vera, 2 Dec. 2020, vera.org/state-of-justice-reform/2017/the-state-of-opioids. Thornton, Mark. “Alcohol Prohibition Was a Failure.” Cato Institute, 22 Sept. 2020, cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/alcohol-prohibition-was-failure. About the Author:

I am N.C. Cai. I am a Chinese American Marxist Feminist. I am interested in socialist feminism, Western imperialism, history, and domestic policy, specifically in regards to drug laws, reproductive justice, and healthcare.

1 Comment

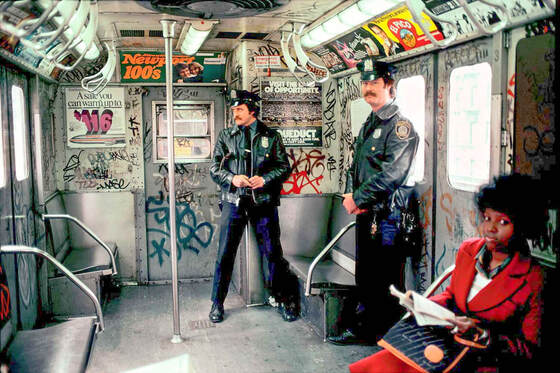

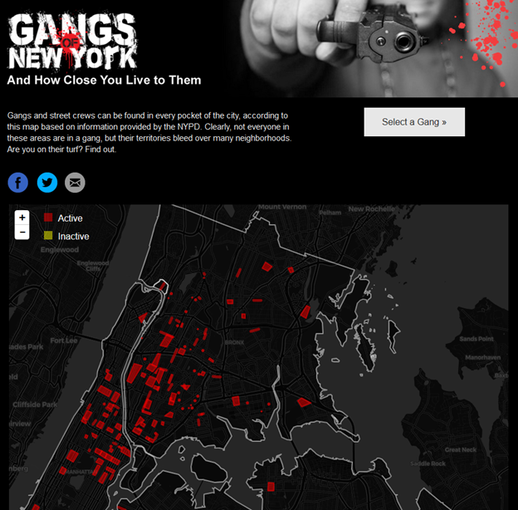

In a previous essay, I gave a brief history of the U.S. Government’s “War on Crime” and how this led the “Land of the Free” to be the world’s number-one prison state. The success of “law and order” narratives from Nixon to Reagan to Clinton, were not the work of these administrations alone. They were bolstered by media representations amplifying the threat of crime and portraying it in a racialized fashion. Here I will explain how the media has developed a symbiotic relationship with “law and order” centers of power which produces high ratings but also misrepresents the reality of crime. Richard Nixon, who declared the “War on Crime” after his “Southern Strategy” propelled him to the presidency in 1968, was largely successful due to his ability to capitalize on media reports depicting broad societal disorder with “race-riots” and crime reports taking center stage. A similar media framework was used to characterize Civil Rights movements and left-wing political groups as a unique threat to America. (There’s a reason the Black Panthers made Nixon’s enemies list and J. Edgar Hoover labeled them “the greatest threat to the internal security of the United States.”) The net effect of this was to intensify white peoples’ fears of crime and black militancy making a “law and order” narrative more palatable for the general public. This sort of sensationalized, hysteria-inducing reporting can be seen again during the mid-1980s media panic over the “Crack Baby Epidemic”. Amid the Reagan administration’s “War on Drugs” news outlets across the nation seized on case studies showing a potential link between prenatal exposure to crack cocaine and birth defects among newborns. News reports often characterized crack babies as permanently damaged, who, as future adults, would be unable to care for themselves, thus, creating people who are, at best, burdens to society and, at worst, extremely dangerous. This may be best exemplified by Charles Krauthammer writing in the Washington Post, “the inner-city crack epidemic is now giving birth to the newest horror: a bio-underclass, a generation of physically damaged cocaine babies whose biological inferiority is stamped at birth” comparing them to “a race of (sub)human drones” whose “future is closed to them from day one. Theirs will be a life of certain suffering, of probable deviance, of permanent inferiority. At best, a menial life of severe deprivation.” He finally concludes, “the dead babies may be the lucky ones.” Other “Crack Baby” headlines include: “Drug Babies Invade Schools” (San Diego Union Tribune, 2/2/92), “Crack Babies Born to a Life of Suffering” (USA Today, 6/8/89), and “Crack’s Tiniest, costliest Victims” (New York Times, 8/7/89). This was common fare for those who consumed main-stream news outlets at the time. Unfortunately, the story was bullshit. As the New York Times itself reported in 2009 (around thirty years too late) medical researchers who followed many “Crack Babies” found “the long-term effects of such exposure on children’s brain development and behavior appear relatively small” and are “less severe than those of alcohol and are comparable to those of tobacco.” Even Dr. Ira Chasnoff, whose research inspired much of the “Crack Baby” reporting, insisted from the very beginning that his results were qualified and limited and, in 1992, lamented that his research was misused saying, “It’s interesting, it sells newspapers, and it perpetuates the us-vs-them idea.” And as we have seen Chasnoff’s fears were warranted. Much of the reporting depicted black people as uniquely prone to drug addiction and shamed the mothers with headlines such as “For Pregnant Addict, Crack Comes First” in the Washington Post (12/18/89). Additionally, it is telling that news outlets focused their attention on crack instead of other forms of cocaine. Even the original “Crack Baby” research showed similar effects on children prenatally exposed to powdered cocaine. But the media ignored this choosing to isolate crack, which, conveniently enough, helped legitimize the Reagan administration’s scaremongering over a “crack epidemic” destroying American cities and justified the militarization of police forces as well as the increasingly punitive measures taken against drug use. You might expect the media to have learned to avoid credulously repeating narratives from “law and order” politicians and academics, but you’d be giving them way too much credit. Only a few years after the “Crack Baby” phenomenon, the media was back to reporting “law and order” propaganda. This time the public needed to be afraid of “super-predators”- a term many associate with Hillary Clinton. During a rally in 2016, Clinton was confronted by Black Lives Matter protesters about her statements from 1996 promoting the “super-predator” narrative at a New Hampshire event for her husband’s reelection campaign. In her speech, Clinton touted the “Tough on Crime” policies of Bill Clinton’s administration and spoke of a new type of predator warning, “We also have to have an organized effort against gangs…. They are not just gangs of kids anymore. They are often the kinds of kids that are called superpredators. No conscience, no empathy. We can talk about why they ended up that way, but first we have to bring them to heel, and the president has asked the FBI to launch a very concerted effort against gangs everywhere.” Much of this sort of “super-predator” rhetoric was based on the theories of a conservative criminologist at the Brookings Institution, John Dilulio. Dilulio coined the term “super-predator” in a piece he wrote for Rupert Murdoch’s magazine, the Weekly Standard, positing that due to America’s moral decline, youth are growing more prone to violence and crime with each succeeding generation. Dilulio proposed- and much of the media reported as fact- that “Americans are sitting atop a demographic crime bomb…. What is really frightening everyone…is not what’s happening now but what’s just around the corner—namely, a sharp increase in the number of super crime-prone young males.” These young males would come from the growing number of “elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches” and “those kids who have absolutely no respect for human life and no sense of the future... big trouble that hasn’t even begun to crest.” Many of Dilulio’s theories were reflected in news headlines of the time with gems such as: “A Teenage Time Bomb” (Time, 1/15/96), “Wild in the Streets” (Newsweek, 8/2/92), and “Killer Kids” (Reader’s Digest, 6/93). The fact that youth crime rates had been dropping for years and would continue to do so for years to come did not change the perception that youth were committing an exorbitant amount of crimes. A Gallup Poll (Gallup Poll Monthly, 9/94) found that Americans had a drastically inflated view of the amount of violent crimes committed by people under 18 years old with the average American adult believing young people committed 43 percent of all violent crimes in the U.S. while they actually only accounted for 13 percent of all violent crimes. As Gallup claims, this is largely a result of news coverage regarding youth violence. For instance, a study by the Berkeley Media Studies Group found that more than half of local news stories on youth included violence, and that more than two-thirds of all stories concerning violence involved people under 25 years old. These inflated perceptions of crime allowed the Clinton administration to pass its own “Tough on Crime” legislation in an attempt to break the Republican party’s monopoly on “Law and Order” politics. A more recent example of media outlets’ PR work for law enforcement is the “gang raid” narrative. One of the most blatant examples of this is the “Bronx 120”. Before dawn on April 27th of 2016, 700 officers from the NYPD, ATF, DEA, and Homeland Security conducted a pre-dawn raid on the Eastchester Gardens and Edenwald House housing projects, arresting on conspiracy charges what they claimed were 120 gang members who were the “worst of the worst.” Even before the raid had occurred law-enforcement officials predicted news outlets would uncritically reprint the official narrative and run tabloid headlines about “urban gangs” and “violent thugs”. And how did the media respond? By doing exactly fucking that. On the day after the raid, the Daily News ran the headline, “87 Bronx Gang Members Responsible for Nine Years of Murders and Drug-Dealing Charged in Largest Takedown in NYC History”. The reporters not only repeated official claims that all these people were gang members, but they also posted several photos of those arrested, going on to describe them as “hoodlums” and “unrepentant gangbangers”. These may have been the wrong descriptors to use as a recent study out of CUNY has shown the majority of those arrested in the raid were never even alleged by officials to be gang members. These were mainly people who lived in public housing being swept up in the dragnet of a massive raid, held without bail as gang members, and forced to accept plea-deals instead of face notoriously unfair conspiracy trials. But the actual consequences for these people do not matter. As Adam Johnson, contributor for FAIR, put it, “These high profile “gang raids” are, above all, PR operations designed to help pad budgets and justify unusually harsh prosecutions. It’s not until years later, after trials and FOIAs and academic reports, that we learn how thin the narrative really was. But by then it’s too late.” All these examples were major media stories with articles appearing in many national news outlets, but distortion seeps into everyday crime-reporting as well. In general, reporting on crime shows black people committing crime disproportionately compared to the share of crimes they actually commit. For example, a Color of Change study on local news crime-reporting in New York City found that black people were shown committing 75% of crime- a full 24% higher than their actual share (51%). Additionally, black suspects of a crime are shown in a more dehumanizing way as compared to white suspects. One study of the Chicago media by Robert Entman found that black people (38%) are more likely to be shown in restraints compared to white people (17%), thus conveying the message that black people are more dangerous and in greater need of restraint. Additionally, the study found that news reports were more likely to show mug shots for black subjects than white, and portray black people less as individuals, referring to black suspects by name only 39% of the time compared to 65% for white suspects. Entman argues the overall effect this has is to render black people as more violent, and de-individualizes them turning them into one homogenous group. Further, many media critics have been questioning the journalistic credibility of a large amount of crime reporting. Many local news stations get their information about crime directly from the police- some even going as far as seeming to copy-and-paste police press reports. This has the obvious effects of repeating police narratives and stoking fears of crime, but it also decontextualizes the crime and the individual’s history by acting as a glorified police blotter. As usual, the goal is to inspire fear. People need to fear getting mugged or else they may think twice about their local police rolling down the road in a tank. A particularly egregious example of this was in the months prior to the “Bronx 120” raid, the NYPD and US Attorney’s Office released to the press war maps of the Bronx depicting alleged gang dominated areas. The Daily News went as far as to turn it into an interactive map which was linked to coverage on the raid. Many observers have questioned the veracity of this map. Adam Johnson wondered, “Who knows if the color-coded areas provided by Bharara (US Attorney) and the NYPD actually correlated with ‘gang control’? Since the majority of those arrested in the Largest Gang Takedown Everweren’t actually in a gang, one can reasonably suspect these maps were just generalized, PR-driven marketing materials.” For its part, the Daily News said, “Obviously, not everyone in these areas are in a gang.” And here we have come full circle. The police need public support for their growing number of raids and the media needs the raids for salacious crime stores that write themselves (or taken directly from police statements). It should come as no surprise that these media panics coincided with the mass expansion of the U.S. carceral state. The “Crack Baby” panic came at the same time as the Reagan administration’s “War on Drugs” which targeted crack users specifically for especially harsh punishment. Similarly, the “super predator” narrative was popular preceding the Clinton administration’s own “tough on crime” legislation, including establishing harsher penalties for juvenile offenders. This latest string of reporting on “gang raids” has essentially been a marketing campaign for RICO busts which many have criticized. Journalist Josmar Trujillo commented, “the continued use of conspiracy laws in poor communities of color like an atomic bomb is not justice. We’ve clearly over-criminalized black and Latino youth across the board, but RICO is particularly harsh and inappropriate.” The aggregate effect of these media tendencies is to create a distorted view of crime for the public, supporting a growing police state. This distortion also promotes a racialized view of crime, portraying black and Latino people as uniquely inclined to criminality, justifying the hyper-criminalization of these communities. This has been a major contributor to the rise of a system of mass-incarceration preying on poor black and brown communities. Instead of addressing the main root cause of crime in these communities, which is poverty, media representations of crime promote strict and heavily punitive policies which exacerbate problems by removing members from their communities and placing a stigma on them that near completely ruins their future economic opportunities. In all these ways, media outlets have aided and abetted the “law and order” agenda, expanding the power of the carceral state and law-enforcement to unprecedented levels. As long as media outlets continue to promote a distorted image of crime, developing policies to best address criminality will be increasingly difficult because the public will not have an accurate understanding of the problem. We need an entirely new paradigm for talking about crime which does more than credulously regurgitate police claims, instead attempting to accurately contextualize the causes of crime in communities and endorsing a less punitive framework for dealing with those who break the law. About the Author:

I'm Alex Zambito. I'm born and raised in Savannah, GA. I graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 2017 with a degree in History and Sociology. I am currently seeking a Masters in History at Brooklyn College. My Interest include the history of Socialist experiments and proletarian struggles across the world. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed