|

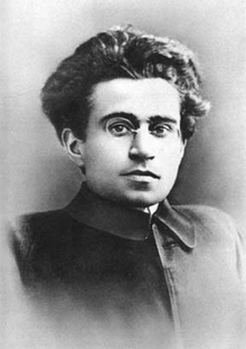

The worldwide campaign to inject experimental “vaccines” into every living person on earth is reaching a predictable resistance point after only 5 months. No sales job has ever been so pervasive, so rapid, so insistent since, well, since Hillary Clinton’s failed 2016 campaign spent 4 years blaming Russia for losing to Donald Trump, fire hosing at full blast a flood of bizarre conspiracies out of every possible media nozzle about hapless buffoons like Carter Page into brains that today zombie walk onward like a kind of undead permanent haze consuming your Aunt Josie. Now comes the shaming campaign, which will be targeted most heavily at the working class by a media machine so omnipresent George Orwell couldn’t have conceived it better. The working class is used to being sold a bill of goods concocted yesterday for the sole purpose of profit, then scolded for not buying the bill of goods. Refusing this bill of goods is entirely reasonable for countless reasons, not just typically anti-vax reasons. First, the working class possesses more public information about how long one’s penis stays hard from a Viagra television ad than about potential side effects (let alone long term) of COVID-19 “vaccines”. The FDA has waived nearly every roadblock that would fully inform any patient’s consent (among other waivers). In fact, the most any worker truly knows about these brand new, wholly experimental “vaccines” is their corporate identity. The Pfizer, The Moderna, The Astra Zeneca. Second, none of these “vaccines” claim to prevent infection. Not one. Here we see capital even exerting power over the understood meaning of “vaccine”. The word itself is completely meaningless at this point. Third, it’s entirely possible these suboptimal “vaccines” succeed mainly in providing a breeding ground for more infectious and more deadly variants to evolve, by putting the body’s own immune system in the back seat in favor of vaccine induced responses that are barely effective against not just infection with the original COVID virus, but totally powerless against variants. One scientist, a fellow named Geert Vanden Bossche, is even convinced that any mass vaccination campaign in the midst of a pandemic is a colossal catastrophic error that will eventually breed some super virus far worse than what we’ve seen to date. The working class has already seen such a dynamic with flu shots that don’t really work, and antibiotic over-prescription making antibiotics less effective over time. An oldie, but a goodie! Thus, in this “vaccine” campaign, now that we’ve reached the point people reasonably refuse it, we will soon see capital rolling out its coercive power because acquiesced consent is resisted. This brings us to Gandhi and Gramsci. Pour the coffee, grab a cannoli. Antonio Gramsci was a founder of the Italian Communist Party born in 1891 on Sardinia, the large Mediterranean island off the east coast of Italy. Unlike so many Italians of his era (like my great grandfather Anthony Russo, born a year earlier in Sicily), Gramsci did not make it to America. Instead, Gramsci grew up on Sardinia into a precocious, though always sickly, brilliant kid intent on revolutionizing Italy. You can visit his childhood home online here. Antonio Gramsci, 1916 By 1926, only 35 years old, Gramsci had become so dangerous, Mussolini threw him in prison, where Gramsci slowly rotted to his death in 1937 at the age of 46. “For twenty years we must stop this brain from functioning,” Mussolini’s prosecutor declared. Alas, Gramsci’s brain did not stop. Despite the agony of constant sickness in a fascist jail cell, Gramsci wrote his Prison Notebooks, 3,000 pages of philosophic thought on every possible topic imaginable; an incredible feat. Those prison notebooks slowly emerged in translation to English in the 1950’s. Over time, Gramscian thought began to transform radical leftism, until today, it forms the bedrock of the rising 21st century left; Gramsci’s theory of “cultural hegemony”. Cultural hegemony is like wearing clothes. We do not walk around naked. Our “common sense” (a term Gramsci relies on) is to wear clothes. Similarly, we hold in the same spot in our brains the logic of markets, profit and loss, as if it is a cosmic truth; capitalism thus becomes as second nature to us as wearing clothes. Gramsci’s contribution is this consent vs. coercion. Capital does not coerce its power (though it holds such power in reserve); instead, it tricks us to obey the value system of capital by our own consent. Just as no one coerces us to wear clothes. We enforce being clothed, and capitalism, ourselves, without thinking, because both are cultural norms of behavior. This is Gramscian thought at its core; the idea that capitalism enforces itself (its “hegemony”) through the voluntary acquiescence of the masses to the value system of capital. America occurred to Gramsci in prison quite a bit. He wrote about us most toward his final years, 1934-1936, thus it’s a bit messy. “Americanism and Fordism” Gramsci called our world, focusing on the processes of production pioneered by Henry Ford’s assembly line. America, Gramsci thought, was creating a specific type of human, the capitalist human, who would fit into capitalism the way the guy with that particular bolt on the Model T fit into Ford’s assembly line. “Hegemony is here born in the factory”, Gramsci wrote of us. For a look at how this plays out in the discourse of the American left today, this 2017 Jacobin article is useful. In 1934, Gramsci observed with prescience that our peculiar development “has left the American popular masses in a backward state,” concluding that in America, “the fundamental question of hegemony has not yet been posed.” It still hasn’t been, but may soon be. Nonviolent war? How? To create a new value system we enforce ourselves by our own consent, Gramsci proposes a series of “war” metaphors. He splits “war” into “war of movement”, the traditional conception of military frontal attack, “war of position”, the seizing of ground for the purpose of holding it permanently, and, almost as an afterthought, “underground war”, when he wrote briefly of Gandhi, around 1930-1932. “Thus India’s political struggle against the English knows three forms of war; war of movement, war of position, and underground warfare. Gandhi’s passive resistance is a war of position, which at certain moments becomes a war of movement, and at others underground warfare. Boycotts are a form of war of position, strikes of war of movement, the secret preparation of weapons and combat troops belongs to underground warfare.” Gandhi, to the contrary, saw nothing “passive” or “underground” about civil resistance. Quite the opposite. “I for one have never advocated passive anything”, Gandhi says in this (suitable for training) set of clips from Richard Attenborough’s 1982 film of his life. Because orthodox Marxist doctrine of the time tended to rely on violence, Gramsci’s “war” metaphors applied to Gandhi reveal Gramsci grappling in his Prison Notebooks with the impotence orthodox Marxism imposes on itself by relying on violence to make change. Gramsci tries to fit Gandhi into this war metaphor, or that one. But after all, Gramsci’s entire theory is about ideas and value systems; consent not coercion. The great genius of Gandhi is the power of this simplicity. Saying “no”, nonviolently, is a direct strike into the heart of capital’s cultural hegemony, creating a new common sense, enforced by consent of all, not coercion by a few. Applying Gandhi to adjust Gramsci, we challenge capital’s cultural hegemony by actively (not “passively, nor “underground”) nonviolently disobeying it. As Dr. Martin Luther King knew, in Gandhi, the “praxis” of nonviolent civil disobedience is self evident. “Be the change you wish to see.” What’s this got to do with COVID? You will rapidly encounter the coercion capital holds in reserve to enforce itself if you refuse the “vaccine”. Capital will fight back. The full weight of capital’s cultural hegemony will rain upon you if its hegemony is threatened by refused acquiescence. Such a fight is precisely as existential to our value system as if instead of wearing clothes we all decided to go naked from now on – we would certainly meet coercion immediately upon being seen without clothing. That is the difficulty in saying “no” to capital’s cultural hegemony; it must be said constantly, loudly, daily, often publicly in the face of severe consequences from capital’s cultural hegemony struggling to survive our nonviolent assault upon it. It is here, in the consistency of saying “no” to capital’s hegemony, we may see Trotsky’s “permanent revolution”. War it most certainly is; saying “no” to capital’s cultural hegemony triggers Gramsci’s “war of position”, such as a boycott, or “war of movement” such as a strike, often both, simultaneously, and much else in response from capital’s coercive power. Such a commitment demands constant struggle, hard work, suffering, and pain. Violence is easy and quick. Nonviolence is anything but. Gandhi is correct that “truth and love” always win, but as any (good) Christian knows, loving your enemy, your neighbor as yourself, every single day, is an endless path, whose journey is often its only earthly reward. All these forces will be evident once you refuse a COVID “vaccine”, including the ultimate result inherent to the theory of nonviolence. If your nonviolent civil disobedience is just (or at least reasonable, as refusal to take the COVID vaccine most certainly is), and based in “truth and love” as Gandhi’s theory requires, coercive attacks against your disobedience of unjust hegemony will only backfire against the unjust value system your disobedience rejects, growing a new cultural hegemony despite (and in response to) the coercion of the few. The new value system supporting your saying “no” will inevitably stand victorious over the coercion of the unjust old, building a new hegemony destined to enforce itself by the just consent of all of us. Such change happens, and can only happen, one person at a time. AuthorTim Russo is author of Ghosts of Plum Run, an ongoing historical fiction series about the charge of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg. Tim's career as an attorney and international relations professional took him to two years living in the former soviet republics, work in Eastern Europe, the West Bank & Gaza, and with the British Labour Party. Tim has had a role in nearly every election cycle in Ohio since 1988, including Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Tim ran for local office in Cleveland twice, earned his 1993 JD from Case Western Reserve University, and a 2017 masters in international relations from Cleveland State University where he earned his undergraduate degree in political science in 1989. Currently interested in the intersection between Gramscian cultural hegemony and Gandhian nonviolence, Tim is a lifelong Clevelander. Midwestern Marx's Editorial Board does not necessarily endorse the views of all articles shared on the Midwestern Marx website. Our goal is to provide a healthy space for multilateral discourse on advancing the class struggle. - Editorial Board

8 Comments

4/30/2021 Antonio Gramsci and Political Praxis in the Materialist Theory of History. By: Sebastián LeónRead NowIn commemoration of the 84th anniversary of his death. Antonio Gramsci is one of the most relevant theorists in the history of Marxism - he is also one of the most misunderstood. Self-proclaimed heterodox leftists of all latitudes have made “neogramcism” their banner, finding in the Sardinian revolutionary a symbol of the break with real socialism, Marxism-Leninism and the materialist theory of history. Perhaps the best known figure in this intellectual trend has been the Argentine Ernesto Laclau, who once again made a key concept such as hegemony fashionable in the academic mainstream. Laclau defined his neogramscism as "post-Marxist", having completely abandoned historical and dialectical materialism, and conceived of social reality as a fundamentally discursive, unstable and radically contingent construct, in which the different forces dissatisfied with the present social arrangement could, through the elaboration of highly porous ideas and slogans, join a political force capable of challenging the common sense of society to the powers that be (that is, hegemony). Here, the conquest of socialism and communism gave way to a "radical democracy", in which every area of social life was left open to democratic deliberation to reconfigure the established order. It is necessary to differentiate Laclau, as well as other self-proclaimed “neo-Gramscians” and followers of Gramsci (whether they are “post-Marxists” or “heterodox Marxists”), from the man himself. For, although there are many who seek to decouple Gramsci and his thought from Marxism-Leninism, his effort cannot be understood if it is not as the attempt of a communist, committed to the revolutionary spirit of the October Revolution, to bring Marxist theory to life in territories that had previously remained unexplored. For, if the Bolshevik triumph had captured the imagination and hopes of Gramsci and a whole generation of Western revolutionaries, the reality of post-World War I Europe forced them to confront failure and the rise of reaction. Gramsci the Bolshevik One of the things that is fascinated about Gramsci is the extent to which he emphasizes the role of subjectivity and political will over the relentless inertia of the relations of production and the productive forces. There are those who think that the construction of socialism and emancipation has more to do with the will of human beings than with the creation of certain material conditions that make it possible; however, one must understand the weight that Gramsci gives to the subjective dimension of politics in its context. The Bolshevik triumph in Russia represented for him “the rebellion against Marx’s Capital ”, insofar as it embodied the triumph of a Marxism (that of Lenin) that came to be understood fundamentally as“ concrete analysis of the concrete situation ”with a view to the strategic organization of political action, over the positivist orthodoxy of the Second International, which clung to a linear and evolutionary model of history, in which the backward countries had to largely imitate the history of the West (necessarily having to go through industrial capitalism and the formation of liberal democracy before attempt a socialist revolution) before making their own. The Social Democrats of the Second International would place their hands on their head with the events in Russia, where the popular masses - mostly peasants - carried out the first successful socialist revolution of the 20th century. These events would profoundly mark a socialist like Gramsci, whose homeland was part of the southern periphery of Europe. However, none of this implied a voluntaristic understanding of politics: on the contrary, the Italian communist understood perfectly that the possibility of the Russians to create a socialist society was anchored in the availability of advanced technical-scientific resources in other parts of the world, which could be implemented by the communists to develop their productive forces without handing over the reins of government to the bourgeoisie. The emphasis on revolutionary organization and will did not imply a disregard for the objective conditions that constrained them; on the contrary, the consideration of these conditions should give rise to a form of collective action that found in the present an opportunity to make history, without applying abstract schemes alien to the singularity of the context. If Gramsci emphasized the weight of human agency, it was always from the coordinates of Leninism, which he saw as a truly dialectical materialism, which marked a distance with a mechanistic materialism, as harmful to revolutionary theory as voluntary idealism. Civil society, hegemony and historical bloc However, the context that the Italian Communists would have to face would be very different from the Russian one. With the rise of fascism, Gramsci, who had become head of the CPI and had been elected deputy, would be put in prison, and would remain there practically until the end of his short life. It would be there where he would elaborate the bulk of his theoretical writings, gathered in the famous volume known as The Prison Notebooks. In his writings from this stage of his life, Gramsci touches on a host of highly relevant topics, from history and economics to politics and philosophy, passing through education and culture. However, if there is an axis that articulates this scattered compendium, this will be the problem of the defeat of socialism in Europe (in particular, in Italy): why had the winds of change coming from the East finished evaporating? And why had the bourgeois reaction managed to take hold where socialism and the working class had failed? It is from this fundamental concern that Gramsci's interest in the question of hegemony arises. In his opinion, the dominance of the capitalist class over the whole of society could not be understood if it was reduced exclusively to a form of violent coercion (political or economic); rather, the power of it was to be thought of as an articulation of coercive force and persuasion. The first would correspond to what Gramsci called "political society": the strictly coercive apparatuses of the State, such as the legal apparatus, the armed forces, the police, etc. However, the second would correspond to “civil society”, which was rather the space of consensus and persuasion, where the beliefs, values and norms shared by the different members of a society were produced: the family environment, educational and religious institutions, the media, unions, etc. It was in the context of thinking about the formation of this sociocultural "common sense" that Gramsci recovered and expanded the Leninist concept of hegemony, which would come to refer to the political domain of a social class (the bourgeoisie), anchored in its pact with other social classes (such as the petty bourgeoisie) and their undisputed control of the cultural field, making common sense of their particular interests and worldview. From his point of view, it would have been this form of hegemonic control, and not its coercive power, that would have allowed the bourgeoisie to subdue the progressive forces of the continent and strengthen its dominance. It would be these theoretical elaborations that would lead Gramsci to take an interest in fields that Marxist theory had typically relegated to a more marginal place, such as the culture, tradition and faith of the popular classes. From his point of view, the Bolshevik triumph in Russia, as it had occurred in the context of war, had only been possible because the aristocratic and bourgeois elites had not managed to consolidate hegemony, and this allowed Lenin and the Bolsheviks to win in a war of maneuvers (basically, defeating them in an open confrontation in the period of the Russian Civil War). On the other hand, where the hegemony of the bourgeoisie and its allies was entrenched, the only way to seize political power and transform the relations of production was through the formation of a “historical bloc” of a “national-popular” character. With the proletariat at the head, an alliance of the popular or subaltern classes (poor and middle peasants, progressive layers of the petty bourgeoisie, and, in a context such as Latin America, the indigenous peoples) had to be formed which, united by a popular progressive culture, (through a new philosophy and a new morality, new artistic and literary expressions, and a new spirituality that articulates the experiences of the people in a key revolutionary manner) could be transformed into a counter-hegemonic force, ready to contest the bourgeois common sense of society in a "war of positions", intervening politically and finally fracturing capitalist control of the means of production. A good recent example of how the consolidation of this popular hegemony can not only win the ideological dispute to the bourgeoisie, but also guarantee the vitality of a revolutionary process, is the recent victory of the MAS in Bolivia after the coup against Evo Morales in 2019. Despite the tragic political defeat, the forces of reaction could not finish imposing themselves on Bolivian society, since the profound changes in the national culture carried out by the MAS during its years in power, had earned it the massive support of a heterogeneous but ideologically favorable people for their political project. For this reason, eventually the coup plotters had no choice but to stop postponing the elections and accept their defeat and the return to power of their enemies. Of course, the coup against Morales also leaves the lesson that a victory in the war of positions does not guarantee the uninterrupted continuity of the revolution. It is also necessary to be prepared to win in the war of maneuvers, to defend by arms the transformation of society when the reactionaries make it necessary. However, it is clear that the thought of Antonio Gramsci, far from implying a break with Marxism-Leninism, represents a crucial, truly dialectical development of the materialist theory of history, one that is of great importance for thinking about the context of contemporary bourgeois democracies. AuthorSebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Translated and Republished from Instituto Marx-Engels.

|

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed