|

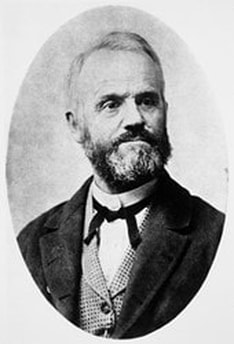

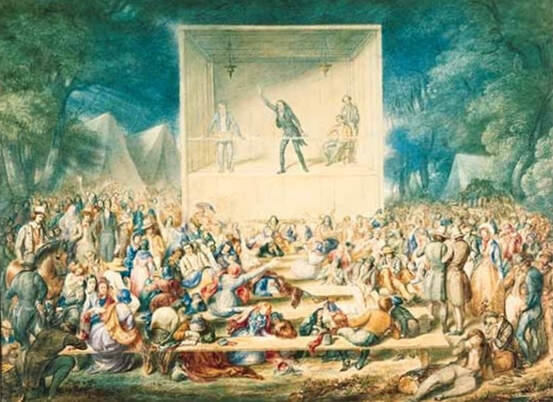

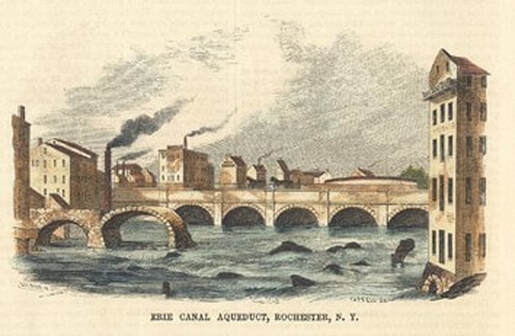

12/1/2020 Heaven on Earth: Society, Socialism, and the Soul in Western New York (1825-1848). By: Mitchell K. JonesRead NowMarxist scholars have often looked at religion merely as a method of social control and not as a potentially emancipatory counter-hegemonic force. Despite religious ideology’s historic use in manufacturing the consent of the exploited class, it has as often been used as a rampart against the most excessive byproducts of that exploitation. The Second Great Awakening movement in 1830s Western New York arose as a method of ruling class hegemony, but transformed into a radical movement that challenged the emergent Market Revolution. The Second Great Awakening became a catalyst for the explosion of utopian socialism after the Market Revolution’s first economic depression in 1837. Christian spiritual leader John Humphrey Noyes argued the utopian socialist movement in 1840s America was a continuation of the Second Great Awakening and the teachings of Charles Finney.[1] While many of the socialists of the Owenite and Fourierist periods were atheists or freethinkers, the earlier and more institutional communist societies were religious. Christian groups like the Shakers, the Zoarites and the Inspiratioists all lived communally in America before secular socialist Robert Owen first visited in 1824. Noyes believed socialism should not be separate from religion.[2] The revivalist religious tradition inspired individuals to reform their souls. For Noyes, only religion provided sufficient “afflatus” or collective motivation to carry out the work that socialism required.[3] He argued that two elements, spiritual enlightenment and worldly communism, were present in the early Christian church.[4] His attempts to reconcile religious revivalism and secular socialism resulted in one of the most successful experiments in utopian socialism in North American history. His “bible communist” society at Oneida, NY lasted from 1848 to 1881. It had the most longevity of any of the North American utopian socialist experiments of the nineteenth century. “Bible Communist” John Humphrey Noyes Workers and the small business class often came to socialism through religion. Religiosity was a common response to the economic changes taking place in Upstate New York in the 1820s. Rochester, New York was an epicenter of economic growth driven by the Erie Canal. According to historian Carol Sheriff, “From a middle-class perspective, the Canal had become a haven for vice and immorality; the towpaths attracted workers who drank, swore, whored, and gambled…. These canallers provided a daily reminder of what fluid market relations - and progress - could bring.”[5] By the 1830s, many Rochesterians felt the Market Revolution encouraged an increasingly sinful lifestyle. The drinking, violence, racism and misogyny characteristic of canal worker culture in Western New York had devastating effects on the workers’ health, security, safety and prospects for social mobility. Historian Peter Way argues that while working class communities offered a measure of solidarity and autonomy to canal laborers that the market did not offer in the 1820s, they just as often encouraged anti-social behavior that divided the working class, keeping them in a subjugated position.[6] Faced with working class culture’s failure to uplift their economic station, conscientious laborers turned to the religious radicals of the business class who had both the motivation to seek a new economic system and the economic power to put such a new system into place.[7] Western New York became a fertile atmosphere for experimental views of society. Mobile tent revivals had already swept through the region as part of the first Great Awakening in the 1730s and 40s. By the 1820s, the Western frontier near Rochester, New York was the epicenter of the Second Great Awakening.[8] Itinerant Methodist minister Charles Finney, who came to Rochester in 1830 on a mission to save Rochesterian souls, was the standard-bearer for the Second Great Awakening. Methodist revival, watercolor from 1839 Perfectionism and millenarianism were key theological doctrines of the Second Great Awakening that directly influenced the emergence of utopian socialism. Christian perfectionism is the idea that humankind can achieve perfection on Earth. Millenarianism is the belief that Jesus Christ will return to earth for a second time and he will rule for a thousand years. Perfectionist millenarianism argued true servants of God must create a paradise on Earth to pave the way for the thousand-year reign of Jesus the Lord. Historian Paul Johnson writes: The millennium would be accomplished when sober, godly men - men whose every step was guided by a living faith in Jesus - exercised power in this world. Clearly, the revival of 1831 was a turning point in the long struggle to establish that state of affairs. American Protestants knew that, and John Humphrey Noyes later recalled that, ‘In 1831 the whole orthodox church was in a state of ebullition in regard to the Millennium.’[9] Radical ministers John Humphrey Noyes and James Boyle were part of the Second Great Awakening movement. Boyle joined the Northampton Association, a so-called “Nothingarian” community loosely inspired by the teachings of French socialist Charles Fourier. The Northampton Association later became a wing of the New Church, an emergent religious movement based on the teachings of 18th century Swedish Lutheran mystic Emanuel Swedenborg.[10] Noyes, originally a Congregationalist, on the other hand, formed the Oneida Community of Bible Communists in Oneida, New York.[11] These examples make it clear that the attempt to establish a Heaven on Earth led some to believe that a radical restructuring of society was necessary and become leaders in the movement. Most are familiar with the cliché attributed to Marx: “Religion is the opiate of the masses.” Most are not aware of the whole quotation. In his seminal critique of the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Marx wrote, “Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”[12] Marx was saying that religion was a response to and a coping mechanism for the suffering of the oppressed. Religion lessened the suffering of the oppressed, but it was also a revolt against the conditions that caused such suffering. Marx argued that reason, unobscured by religious zeal, would lead to liberation. He wrote: Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain without fantasy or consolation, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower. The criticism of religion disillusions man, so that he will think, act, and fashion his reality like a man who has discarded his illusions and regained his senses, so that he will move around himself as his own true Sun. Religion is only the illusory Sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself.[13] What was the living flower Marx was arguing those seeking liberation must pluck? Marx said it was a social reality illuminated not by religion alone, but by the earnest search for truth. Still, the fact that religion served such a unique function for the oppressed means study and critique of religion is of utmost importance. How else are those interested in the emancipation of the proletariat to understand the complex social relationships enforced and reinforced by religion? Historian Paul E. Johnson answers that it is not enough merely to explain the social and economic conditions under which religion arose. Those who are curious about systems of control must look at the relationships religions enforce, reinforce and reproduce as social facts. In A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, Johnson’s study of Finney’s religious revival movement in Rochester, New York from 1830 to 1837, he aptly explains the material basis for the movement’s rise. However, he does not account for how the movement shifted after the 1830s. Johnson argues that control of the private morality of a newly autonomous proletariat made revivalism especially attractive to the bourgeoisie.[14] Prior to the 1820s, workers lived with their employers. However, as they moved out of the bosses’ homes they developed autonomous lives of their own.[15] Proletarian autonomy made the bourgeoisie nervous. Religiosity was a convenient way to maintain social control.[16] Johnson writes from a Marxian perspective, but fails to look deeper into the meaning of Marx’s ideas on religion. He thus fails to account for the revivalist movement’s influence on utopian socialism in America, especially in Western New York. Utopian socialism offered the proletariat a radical alternative to capitalism. Whatever the roots were, revivalism contained emancipatory elements for the proletariat. It led workers to conclude that it was necessary to reorganize society in order to ameliorate social ills. Erie Canal Aqueduct, circa 1855 Although he takes a Marxian approach, Johnson does not cite or as much as mention Marx once in the entire book. Instead, he cites sociologist Emile Durkheim as his inspiration. Early in the introduction, he invokes Durkheim’s notion of “social facts.”[17] Johnson defines social facts as, “habits and ways of feeling that shape individual consciousness and behavior, yet exist outside the individual and coerce him independant of his will.”[18] He emphasizes how relationships in a community create and reproduce social facts. His research is concerned with how social facts arise and how, through the reproduction of social facts, societies have collectively formed ideas about the world. Johnson argues that religion was an elemental social fact in the nineteenth century as it was used as a form of social control. Prior to the 1820s, when Rochester’s workers mostly lived with their employers, drinking was a form of social cohesion shared between the employer and his employees under conditions the employer controlled.[19] As capitalists favored money and privacy over paternalistic control of their workers the proletariat began to move out of the capitalists’ houses. The bourgeoisie shuddered in anxiety over the new, autonomous proletariat. Working class drinking habits made them most nervous. No longer could they control the conditions under which workers drank.[20] Johnson argues this caused the bourgeoisie in Rochester to turn to temperance as a way to control the autonomous action of the workers. Employers’ insistence on sobriety made them likely targets for religious revivalism and in 1830 Charles Finney took advantage of this propensity among the bourgeoisie.[21] Johnson’s arguments contrast with sociological theorist Max Weber’s idealist conceptualization of religiosity and the growth of capitalism. While Weber insists that the spirit of the Protestant ethic initiated the growth of capitalism in America, Johnson argues capitalism revived the Protestant ethic in America.[22] Bourgeois anxiety over a newly autonomous proletariat was the root of Finney’s revivalism. The Rochester bourgeoisie rejected the paternalistic practice of housing employees under their own roof in favor of privacy and amassing private wealth. Still, they wanted to maintain social control over the proletariat. It is easy to see why the bourgeoisie were among Charles Finney’s earliest and most enthusiastic converts. Proletarians soon joined in as their bosses increasingly saw church attendance as an essential trait of a good worker. Religiosity thus became a vetting process for employment.[23] Workers had an economic imperative to join in the enthusiasm of revival. They predictably did so. Workers, due to the precarity of their employment, gave in to the social pressure to join the religious revival. The bourgeoisie and the proletariat cohered in a religious community. The proletariat could feel themselves part of a devout group of elite parishioners. Finney’s ideas of cohesive community, equality of the devout under the eyes of God and the Millenarian belief in building a utopia of Christian believers on earth had emancipatory potential for workers. Johnson misses the potential emancipatory impact of religiosity on the proletariat. Spiritual leader of the Perfectionists John Humphrey Noyes’ communist experiment at Oneida, New York is evidence that revivalism had emancipatory potential for the proletarian class. Johnson mentions Noyes only once in his account. He quotes Noyes during his discussion of Millennialism. Johnson writes: [Charles Finney preached] Utopia would be realized on earth, and it would be made by God with the active and united collaboration of His people…. The millennium would be accomplished when sober, godly men - men whose every step was guided by a living faith in Jesus - exercised power in this world. Clearly, the revival of 1831 was a turning point in the long struggle to establish that state of affairs. American Protestants knew that, and John Humphrey Noyes later recalled that, ‘In 1831 the whole orthodox church was in a state of ebullition in regard to the Millennium.’[24] Christian utopianism, inspired by Millennialism, proved to be a much more advantageous daisy chain for workers than Protestant capitalism. The Millenarians believed that heavenly conditions had to be created on earth to usher in the coming thousand year reign of Christ. The workers at Noyes’ so-called “bible communist” Oneida community attempted to create such perfect conditions. They were equal in all things, the community provided for their needs, they engaged in free love and had full equality of the sexes.[25] Noyes connected the explosion of revivalism in the “Burnt over district” (Western New York) with the later wave of utopian socialism in the “Volcanic district” (also Western New York) in his 1870 study of American Socialisms. He wrote: And these movements—Revivalism and Socialism—opposed to each other as they may seem, and as they have been in the creeds of their partizans [sic], are closely related in their essential nature and objects, and manifestly belong together in the scheme of Providence, as they do in the history of this nation. They are to each other as inner to outer—as soul to body—as life to its surroundings. The Revivalists had for their great idea the regeneration of the soul. The great idea of the Socialists was the regeneration of society, which is the soul's environment. These ideas belong together, and are the complements of each other. Neither can be successfully embodied by men whose minds are not wide enough to accept them both.[26] Noyes goes on to argue that the early Christian church described in the bible book of Acts was itself a communitarian project. His attempts to reconcile religious revivalism and secular socialism were successful. The Oneida Community never collapsed like other contemporary utopian experiments. Noyes fled to Niagara Falls, Ontario to escape statutory rape charges in 1879. His teachings about complex marriage, a form of group marriage where elders collectively chose who was allowed to engage in sexual intercourse, ultimately caught the attention of a Hamilton College professor who organized a campaign against Noyes and the Community.[27] When the Oneida Community voted in 1879 to end complex marriage they also left bible communism behind. The Oneida Community became Oneida Community Limited in 1881. To this day it is the largest supplier of silverware to the North American food service industry. Oneida Community Mansion House Even Marx and his comrade and writing partner Friedrich Engels acknowledged the significance of the religious utopians on the international socialist movement. In an 1844 letter, Engels wrote of the religious communities of the Shakers, Inspirationists and Harmonists, “For communism, social existence and activity based on community of goods, is not only possible but has actually already been realised in many communities in America… with the greatest success….”[28] However, there was a flaw in American utopianism. Engels, himself the son of a factory owner, says of the utopians: Not one of them appears as a representative of the interests of that proletariat which historical development had, in the meantime, produced. Like the French philosophers, they do not claim to emancipate a particular class to begin with, but all humanity at once. Like them, they wish to bring in the kingdom of reason and eternal justice, but this kingdom, as they see it, is as far as Heaven from Earth, from that of the French philosophers.[29] Representatives of the bourgeois class may not be expected to have the answers to the liberation of the proletariat. Noyes' fatal flaw was his failure to adapt his teachings to the changing attitudes within and outside the community. However, Marx said of the utopian socialists, “...the communist tendencies in America had to appear originally in this agrarian form that seemingly contradicts all communism….”[30] Despite his flaws, Noyes may have been on to something when he attempted to reconcile religiosity and socialism. His “bible communist” society at Oneida, NY lasted from 1848 to 1881, much longer than any of the other utopian socialist experiments in North America, and unlike his socialist contemporaries, he was an industrial socialist, not an agrarian.[31] Noyes concluded: Doubtless the Revivalists and Socialists despise each other, and perhaps both will despise us for imagining that they can be reconciled. But we will say what we believe; and that is, that they have both failed in their attempts to bring heaven on earth, because they despised each other, and would not put their two great ideas together. The Revivalists failed for want of regeneration of society, and the Socialists failed for want of regeneration of the heart.[32] The success of liberation theology movements in Latin America in the 1960s and 70s, during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States in the 1950s and 60s and in Palestine to this day bear witness to the truth of Noyes’ insistence that liberation for the working class must seek both the regeneration of society and of the soul. Noyes might have agreed with Marx when he, in 1844, called religion, “the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions.”[33] Johnson’ aptly assesses the material basis for the rise of revivalism, but fails to account for its chimeric change over time. In the final chapter he briefly mentions the rise of the African Methodist movement, to which abolitionist Frederick Douglass belonged, as connected to Finney’s revival.[34] The African Methodist church was instrumental in building power and solidarity between black Americans that, in turn, presented a militant challenge to the Southern institution of race-based slavery. Johnson does not explain where the movement led, only how it gained strength. To be sure, Finney’s revival gained strength as a mode of social control for the bourgeoisie over a newly autonomous proletariat, but once the proletariat joined and took it over it took on a life of its own. Revivalism became a catalyst for the working class movements that swept the United States, especially Western New York, throughout the nineteenth century. Abolitionism, suffragism and utopian socialism all came out of Finney’s revival. The workers weaved living flower of truth that Marx spoke of into the daisy chain of religion creating something truly progressive and emancipatory. Citations [1] Noyes, A History of American Socialisms, 26. [2] Noyes, A History of American Socialisms, 26. [3] Noyes, A History of American Socialisms, 26. [4] Noyes, A History of American Socialisms, 27. [5] Carol Sheriff, The Artificial River: the Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817-1862, (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 138. [6] Peter Way, “Evil Humors and Ardent Spirits: The Rough Culture of Canal Construction Laborers,” The Journal of American History 79, no. 4 (1993): 1400. [7] Paul E. Johnson, A Shopkeepers Millenium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815-1837, (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 121. [8] Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-Over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800-1850, (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 154. [9] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 110. [10] Christopher Clark, The Communitarian Moment: the Radical Challenge of the Northampton Association, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003), 30. [11] Cross, Burned-Over District, 190-191. [12] Karl Marx, “A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” in Eugene Kamenka ed., The Portable Karl Marx, (New York: Penguin, 1983), 115. [13] Marx, “A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right” in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels on Religion, (New York: Schocken Books, 1964), 42. [14] Paul E. Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, NY 1815-1837, (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 9. [15] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 43. [16] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 81. [17] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 11. [18] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 11. [19] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 56. [20] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 60. [21] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 106. [22] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Talcott Parsons trans., (London: Unwin University Books, 1965), 82. [23] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 121. [24] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 110. [25] Charles Nordhoff, The Communistic Societies of the United States, (New York: Schocken Books, 1965), 271. [26] Noyes, A History of American Socialisms, 26. [27] Lester G. Wells, The Oneida Community collection in the Syracuse University Library, Syracuse University and the Oneida Community, 1961. [28] Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Nelly Rumyantseva, Marx and Engels on the United States, (Moscow: Progress, 1979), 33. [29] Frederick Engles, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, trans. Edward Aveling, (New York: International Publishers, 1935), 32. [30] Karl Marx, Marx on America and the Civil War, (New York: Saul K. Padover, 1972), 5. [31] Constance L. Hays, “Why the Keepers of Oneida Don't Care to Share the Table,” The New York Times, June 20, 1999. [32] Noyes, A History of American Socialisms, 27. [33] Karl Marx, “A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” in Eugene Kamenka ed., The Portable Karl Marx, (New York: Penguin, 1983), 115. [34] Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 117. About the Author:

Mitchell K. Jones is a historian and activist from Rochester, NY. He has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s degree in history from the College at Brockport, State University of New York. He has written on utopian socialism in the antebellum United States. His research interests include early America, communal societies, antebellum reform movements, religious sects, working class institutions, labor history, abolitionism and the American Civil War. His master’s thesis, entitled “Hunting for Harmony: The Skaneateles Community and Communitism in Upstate New York: 1825-1853” examines the radical abolitionist John Anderson Collins and his utopian project in Upstate New York. Jones is a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation.

2 Comments

southwesternmarxist

12/1/2020 08:41:25 pm

just wanted to say i love what you're doing with your platform. i've learned a lot in my time following this account and reading the journals you've shared/written. keep it up.

Reply

Lorenzo

12/2/2020 08:22:26 am

Very good article.little details of the story that are not known

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed