|

In any attempt to understand contemporary culture and its artistic manifestations in a materialist manner it is absolutely essential that we attempt to do so in the light of a Marxist critique. There is not, however, only one "official" Marxist approach to the understanding of art. Past attempts to force creative thought into a narrow official mould by means of state sponsored interpretations of Marxism resulted in a separation between genuine materialist theory and the social reality that was being presented. My purpose is not to present the "correct" theory of a materialist philosophy of art but to attempt to lay down what I think to be the four basic features that anyone trying to work out a Marxist aesthetic must keep in mind. These four features will also be useful to those who propose to write materialist criticism of both contemporary "pop culture" as well as so called "high culture." First, it is well known that neither Marx nor Engels consciously worked out a philosophy of art as part of their general worldview. Nevertheless, they made particular judgments on art and their overall positions on historical materialism (in conjunction with these judgments) have been appealed to by their followers in order to support aesthetic theories that were developed later within the context of the Marxist movement. Second, based on the general notions of historical materialism, the social context of art takes on the most important aspect in any Marxist aesthetics. That is to say, approaching art in a materialist spirit, a Marxist philosophy of art bases itself on the social, cultural, and biological factors of human life as the foundation upon which art arises. This, of course, does not distinguish a Marxist approach from a materialist approach in general. This further determination can be made when we consider the following. Third, the notion of contradiction in the dialectical logic inspired by Hegel, as developed by Marx and Engels, and its relation to struggle and the overcoming of such at higher developmental levels are necessarily linked to the basic materialist approach fundamental to a Marxist aesthetic. In this we find the main difference between traditional philosophical materialism and Marxist historical materialism. Traditional materialism, while recognizing the primacy of matter, tended to interpret the world in unchanging mechanical categories. The materialist philosophers of the French Enlightenment, while disposing of religious, spiritual and mystical explanations for the events of the natural world, had no real theory of historical or natural change and development. The materialist philosophy developed by Marx and Engels, on the other hand, by adapting the Hegelian concept of contradiction to materialistically inspired categories of explanation, was able to provide a non-mechanistic explanation of natural and historical change, development and progress. In this combination of materialist philosophy and dialectical method, of which the notion of contradiction is central, can be found the difference between "materialism" and "historical materialism." The correct application, as well as understanding, of contradiction is one of the most vexing problems in the history of Marxist thought. Its abuse led to Marx’s famous comment about his not being a Marxist. I do not intend to go into all of the different interpretations which have been given to Hegel’s views on this subject. I will, rather, briefly outline what I consider a useful way of looking at contradiction as used by Hegel and Marx and Engels and relate this to my claim that it is the basis of any Marxist philosophy of art by showing how one of the most original Marxist thinkers, Christopher Caudwell, employed contradiction in his great work on the origin of poetry: Illusion and Reality. Let’s begin by asking the following question: What happens when one makes a mistake in philosophical reasoning? One of the most common occurrences is that we have been guilty of over-generalization or have dealt with our subject without sufficient knowledge that might have affected the outcome of our reasoning. It is the presence of a contradiction in our reasoning which signals that this faulty way of reasoning has occurred. The function of philosophy is to deepen the analysis, make it less general, and overcome the contradiction while at the same time preserving what is true and valuable in the previous view. This method is then repeated on the new views, and on the views that replace them and is continued as long as we can. Hegel uses the German verb aufheben which means "to lift up," "to cancel," and "to preserve" to describe this process. No one English verb quite catches all these meanings. Contradictions are not therefore mutually exclusive after all. In The Science of Logic Hegel maintained it was very important to keep in mind that such seemingly contradictory opposites as positive and negative, virtue and vice, truth and error, and one could add, illusion and reality, only had their truth "in their relation to one another; without this knowledge not a single step can really be taken in philosophy." Ivan Soll puts it this way in his An Introduction to Hegel’s Metaphysics: "The dialectic preserves parts of putatively opposed categories as the necessary elements (Momente) of more concrete categories. But as necessary elements of a more concrete category their mutually exclusive character is removed or negated. These categories are both preserved and negated - they are aufgehoben." This method was taken over by Marx and Engels and applied to the analysis of history as well as to natural phenomena. The difference in their materialist, as opposed to Hegelian application, is that, as Engels points out (The Dialectics of Nature), in the former the contradictions are derived from the actual study of history and nature while in the latter they "are foisted on nature and history as laws of thought." When it comes to Caudwell, we see his use of contradiction throughout all the major discussions of Illusion and Reality. According to David N. Margolies (The Function of Literature), "Caudwell had to take a fully dialectical view of literature, seeing literature not as static works but as a process. Literature and society exist in a dialectical unity and thus not only does social existence determine literature, but literature also influences society." But Caudwell uses contradiction in other realms besides literature. For example, he takes Freud’s category of "the instincts" (the source of humankind’s free natural existence) and contrasts it with the category of "the environment" (the source of the repression and crippling of the instincts) and derives the higher category of "civilization" which, Caudwell says, was evolved "precisely to moderate and lessen" the conflict between the other two antagonistic conceptions. We should further note that illusion and reality, which we create and study by means of art and science are not for Caudwell absolutely contradictory conceptions. It is true, he notes, that in many theories these concepts "play contradictory" even if intermingled roles but they are really unified and reflect different (but equally important) aspects of our common world. Our human biological make up and "external reality exist separately in theory, but it is an abstract separation." Caudwell continues, "The greater the separation, the greater the unconsciousness of each." By which he means the more distance we put between "art" and "science" the less we really understand either of them. Contradiction, as used by Caudwell, consists in the refusal to isolate the world into a system of mutually exclusive categories. What appears on one level of analysis as contradictory or exclusive is seen, on a higher level of analysis, to be complementary. He uses this method or argumentation and discussion when he deals with poetry, psychology, epistemology, language, communism, and in virtually every aspect of his philosophy. For this reason he can be located in the tradition of classical and contemporary Marxism. Fourth, one last feature seems to me to be necessary for a Marxist philosophy of art. The fundamental purpose, the raison d'être of Marxism is to be the leading philosophy of the worker’s movement in the class struggle to overthrow the economic system of capitalism. Therefore, a Marxist philosophy of art must, as I define it, link up with the class struggle, directly or indirectly, and, whatever else it may seek to do or explain, provide insights and guidance in that struggle. About the Author: Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. On Saturday January 30, 2021 at 11:30 am central time Dr. Riggins will be presenting a corresponding lecture with a question and answer session in relation to this essay. To be a part of the event email: [email protected]

1 Comment

In Equality as a Moral Ideal, Harry Frankfurt argues that the value of equality is not valued for itself. Rather than viewing equality as an intrinsic good, Frankfurt suspects that the actual intuitive appeal of equality derives from our moral intuition that everyone should have enough. We will first investigate the concept of “enough” on Frankfurt’s account. Then, we will analyze the moral import of making sure everyone has enough under the framework of the “strong sufficiency view.” While we will see that sufficiency for others is indeed a vital moral value, there is still reason to regard equality as good in itself as well. The latter view we will refer to as the “weak sufficiency view,” which I seek to sketch out and defend. The view of Frankfurt’s we wish to analyze is concisely put forward by Frankfurt when he writes, “[W]hat is important from the point of view of morality is not that everyone should have the same but that each should have enough. If everyone had enough, it would be of no moral consequence whether some had more than others” (Frankfurt 21). We will refer to this view as the “strong sufficiency view.” On this view, equality is regarded as entirely lacking intrinsic moral import. For Frankfurt it simply does not matter how the distribution of resources turns out to be in terms of some or other measure of equality—at least as long as everyone has enough. But what is enough? We must be clear that for Frankfurt the extension of the word “enough” is broadly encompassing. We do not mean here enough to barely survive, or enough to hardly live comfortably. Rather, with “enough” we mean enough to flourish. Not only does sufficiency include the basic necessities of life such as food, water, and housing, but also what people need in order to live a meaningful life as they see it. For example, in order for the musically talented to flourish he needs instruments and leisure time to develop his skills. Alternatively, the nuclear physicist needs lab equipment, textbooks, and raw materials to do the work that makes her life feel meaningful to her. The conception of sufficiency on this view is wide-ranging, but the main point is that it is the amount of resources (social, material, and beyond) that someone needs in order to fulfill their potential as they see it. In this way, we see a strong parallel with John Rawls’s ideal of society promoting the ability of each individual to have genuine self-respect (Rawls, A Theory of Justice 386). While they strongly differ in their views on egalitarianism as a whole, both of their views are at least partly motivated by an impulse to preserve the cherished values of autonomy and self-determination that underpin modern liberal democracies. To anyone on the political left, the idea that everyone should have enough to flourish is unlikely to garner much criticism. What about a libertarian? Someone like Robert Nozick would disagree strongly with the idea that morality demands that we be concerned with everyone having sufficient resources. Rather, from the strict libertarian perspective, what is morally relevant is consent. For the libertarian, it doesn’t really matter if almost an entire society lived in poverty while some live in lavish conditions with more resources than they could use in a thousand lifetimes. As long as those conditions arose out of voluntary transactions between individuals, there is no moral claim to be made against such a distribution. What the libertarian fails to understand is that without enough to live well people are not in a position to genuinely consent in a free-market system. Given the inevitable concentration of resources into the hands of a few in modern global society (see Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, etc.) a large portion of a free-market society must engage in menial labor in order to survive. In a free market system, there is no real choice. Is it genuine consent if failing to engage in menial labor will result in your children starving to death? Is it genuine consent if failing to engage in menial labor will result in your mother dying from diabetes because she can’t afford her insulin? There is no consent where one does not have a legitimate chance of survival if she says “no.” What if we provide everyone with enough? It seems then that no one would be forced into menial labor—one could say “no” to those jobs and still be perfectly able to survive and live a meaningful life. While one may say that’s far-fetched—we will always need menial laborers—I would urge him to look at the rapid development of technology. Far from far-fetched, it seems inevitable that large portions of the simple, menial jobs of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty first centuries will vanish within the next ten years. The dreaded decline of the trucking industry, one of the largest employers in the United States as of this writing in 2020, is a particularly poignant example. What are they to do when all the trucks drive themselves? What will their “consent” in the “free” market look like then? We can see now that providing people with sufficient resources to live their best life (as they see it) actually enables consent! By securing sufficient economic resources for everyone, people’s freedom will grow exponentially. Let us picture our level of freedom as some rough estimate of our available choices. It is simply undeniable that a society in which everyone unconditionally had enough to live well would result in those people have more choices available to them to design their conception of the good life. How many poor kids in the United States long to become doctors, lawyers, professors, or nurses, who will never be able to do so because their family has never had enough to invest in their education? It is an insidious falsehood that the only motivator for human behavior is profit. While this is an empirical claim we cannot verify here, I truly believe that there are millions who would pursue these things for their own sakes. The free market profit motive is not necessary for the perpetuation of our society. Everyone should have enough. Let us now introduce an amendment to Frankfurt’s strong sufficiency view. We have established that everyone having enough is vitally important for the legitimacy of a liberal democracy and market system. But that does not mean sufficiency is all that matters. Imagine a society in which everyone had sufficient resources. Every single person has enough to fulfill their conception of the good life, whatever it may be. To be clear, there has not been a single society in the history of the world that has achieved this. But as philosophers we get to imagine. In this society, we will say that a unit of $1/day covers the vast majority of people’s needs. However, there is still a market in society, and some people amass much more wealth than others. We will structure it like this: 90% of the people have a net worth of $36,500 (which would cover $1/day for 100 years); 5% of the people have a net worth of $1,000,000 ($1/day for 2,740 years); and the top 5% have a net worth of $10,000,000,000 ($1/day for 27,397,260 years). Is it really of no moral consequence that these vast inequalities exist? Keep in mind everyone has enough to thrive. There is not a single person in deprivation in this society. For the sake of further clarity, we can imagine this as a worldwide government. Every single human being has enough. However, even in those conditions, there is still a massive power inequality between the three groups. The psychological effects of wealth have been discussed by intellectual revolutionaries from the ancient prophets Buddha and Jesus Christ, to the economists of the nineteenth century and the psychologists of today. It seems extremely unlikely that in any society in which money still exists there would not be people motivated by greed. While, as stated above, the profit motive is not the only motive human beings have for behavior, we know from time immemorial that there are people in every generation who are primarily motivated by this. In short, in a society in which money exists money is a primary vehicle of power. The moral consequence of our inequality here has nothing to do with sufficiency. Sufficiency has been met in this society, and that is certainly a necessary condition for a just society. Ironically, sufficiency is not a sufficient condition for a just society. Any society in which there are massive imbalances of power cannot be considered properly just. To appeal again to our liberal ideals of autonomy and self-determination, a relatively equal distribution of social power is necessary for the genuine expression of these values. Money is the ultimate social influencer in societies in which it exists. If one group of people enjoy far more access to social power than another, those people are much more likely and able to exert their control over the society as a whole to a much greater degree than those without that social power. To have one’s interests, desires, and beliefs manufactured intentionally is a barrier to true autonomy—but even in this society of sufficiency such exertion of control through money would likely be inevitable. We will then call our adapted view the “weak sufficiency view.” On this view, sufficiency is vitally important. No society can be just even if a single person under its sovereignty does not have enough in Frankfurt’s fullest sense. However, we have seen that the distribution of power is also vitally important, and the guarantee of such a just distribution of power cannot be achieved by application of the principle of sufficiency alone. One might wish to object at this point that this defense of egalitarianism is simply a defense of equality as an instrumental good for the sake of maintaining just power structures. However, the value of equality simply is the value of a just power structure between persons. Frankfurt has shown us that it is not the equal distribution of material resources themselves that is important with respect to equality. What is left for us then is the most basic sense of equality between persons, and that is equality between the power of persons. As Rawls says, the value of autonomy is sustained by our regard for all individuals as free and equal persons. The value of equality of power between people underpins even the social value of personal autonomy for all persons. On our weak sufficiency view, we assert that sufficiency is necessary. However, this sufficiency must be accompanied by a reasonably equal distribution of overall resources in order to retain the value of equality of power between persons. We have seen that maintaining a reasonably equal distribution is itself necessary to retain the very principles that constitute the backbone of modern liberal democracies. The long and bitter struggle between the priority of liberty and the priority of equality may never see a practical end in human society, but I believe that a proper analysis of the concept shows that they are mutually intertwined. Liberty without equality of resources cannot be liberty because there is not genuine consent and autonomy between citizens where there are great imbalances of material power. Equality of resources without liberty cannot be equality because there would be great imbalances of power between citizen and state. While liberty and equality are not reducible to each other fully, they are mutually affirming, and one cannot be properly understood without some reference to the other. About the Author:

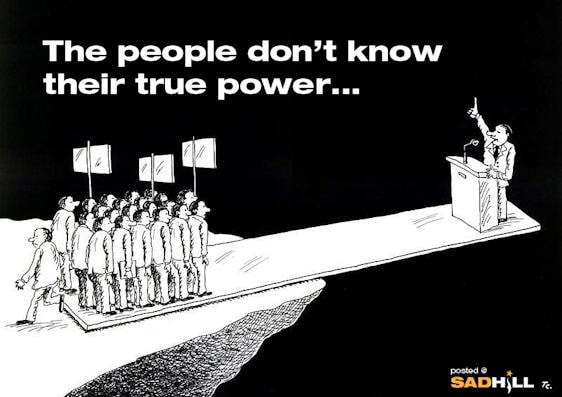

Jared Yackley is an undergraduate student of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. His primary focuses are in epistemology, history, and political philosophy. Yackley hopes to apply the principles of dialectical materialism to contemporary issues, both philosophical and political. The basic logic of democracy is that the people are the final authority in politics. This is the principle of popular sovereignty: that the true sovereign is no high official, no oligarch, no general, no king, but the people. This is of course why we have elections to hold our leaders accountable: before we get to higher-level arguments about representation, responsible governance, or the common good, the first thing that democracy means is that the people are the final authority, who can peacefully overturn their government and put a different one in its place. Until recently, I had thought that everyone in our society basically bought into this premise, with very few exceptions. Yes, this basic conception of democracy is one of the fundamental tenets of the Enlightenment that is hegemonic in our culture today.[i] And yes, if you ask people in the abstract, people will say they believe in popular sovereignty. But it strikes me how often people get it backwards and invert this relationship of accountability. I’ve been voting third party in presidential elections for a while now. This is a decision that I have always given much deliberation in each election. The point here is not my reasons for voting third party, but how others respond when I tell them this. “Voting third party? But why would you throw your vote away like that?” “I don’t think either major candidate has earned my vote, and I’m voting for a candidate who has.” After some discussion of the strategic pros and cons of voting third party, which is typically premised on the idea the both of us have the same goals politically, the conversation then frequently devolves into a mild but persistent chiding of me, and an effort to convince me to vote, as a matter of strategy, for the Democrat. “Well, if you don’t vote for Biden, isn’t that kind of like voting for Trump? Or at least effectively like half a vote for Trump?” I won’t deal here with arguments about voting for an evil that is lesser than another evil, or about how much the two parties differ, or about voting “against” a candidate instead of “for” a candidate, or any of the usual suspects in an argument about tactical voting. These, after all, are tough questions, and a matter of judgment for any given voter. Here I simply want to point to an assumption that sneaks into these discussions: that I, as a voter, have an obligation to support one of the two major candidates, and if I don’t, I am letting the better candidate down. Some people will go so far as to actively shame nonbinary voters for this. When that politician loses, as Hillary Clinton did in 2016, it is not her fault for failing to appeal to more voters, as she should have, but the voters’ fault—they failed to vote for her, as they should have. It was not her responsibility to earn your vote, but your responsibility to vote for her, the reasoning goes. This logic became just another device in the service of removing the blame from Clinton and her lackluster campaign. The opposite party’s voters are not typically chastened like this. I suppose this is because they are perceived to have different political values, goals, and worldviews, whereas I, who “should” be voting Democrat, am presumed to share these things with the Democratic voter I am speaking with. In their minds, I imagine, Republicans don’t deserve this scorn because, even though they are on the opposing team, at least they are playing by the rules and voting for a candidate that won’t “waste” their vote. I, however, am perceived to be on the same team, but I’m sabotaging all their efforts to win the game by not playing it with their optimized strategy. Enemy soldiers may get fired at, but scorn is reserved for deserters. From the perspective of the loyal Democrat, the problem is that I am not voting as I “should”. So, I should be pressured into doing so. What you might notice here is how voter shaming turns upside-down the basic idea of democracy: it holds voters accountable to politicians rather than the reverse. Instead of expecting politicians to earn our votes, we expect each other (when categorized in the appropriate box) to support our politicians. Instead of politicians owing us policies that will work in our interests, we owe politicians votes that will help them achieve their ambitions. In some cases, this voter shaming is only a side dish presented alongside a persuasive argument based on policy differences between the candidates, and that can be part of a healthy discussion on how (and whether) we should vote. I am certainly not arguing against interpersonal debates about how to vote. But in many cases the shame is the main course: you should vote for the Democrat because how dare you. Even worse, it is sometimes claimed that exercising your right to freely vote for whom you choose by voting third-party is somehow a privilege that oppressed voters don’t have the luxury of indulging in. This is clearly untrue, but the more important point is that when voting itself is characterized as a privilege, rather than as a right, the antidemocratic nature of this line of argument is undeniable. After all, when something is a privilege and not a right, it is granted from above and can be taken away under certain conditions. Where does this urge to blame voters rather than candidates come from? Why is there so much voter shaming going on, when we should all be candidate-shaming instead? Maybe social media has set us all up as targets to be critiqued for our politics. Twitter and Facebook have certainly made punching down at least as easy as punching up. It sometimes even seems like the business model of social media is meant to keep us hooked on public shaming and cancellation as a modern ritual of human sacrifice. Or maybe we’ve learned to be fans rather than citizens, and we’ve come to believe that our role is to root for our electoral team to score as many points as it can. Whatever its sources, we can see this logic not just when it comes to elections, but in higher levels of politics as well. In early January 2021, even the most progressive members of Congress balked at a proposal put forward by commentator Jimmy Dore to withhold their votes for Nancy Pelosi as Speaker of the House unless Pelosi promises them a floor vote on Medicare for All. For instance, despite campaigning on the promise of getting a vote on Medicare for All, and despite her repeated claims that the Democratic party needs new leadership, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (along with everyone else in “the squad”) refused to even threaten to withhold her vote.[ii] AOC argued that she didn’t want to risk getting a Republican elected speaker of the House. At first blush this seems to be an understandable concern, but notice what’s already happened here. What assumptions have already been made in order to make these arguments? First, AOC has assumed that if the lone Democratic nominee were to lose, then the Republican leader will automatically win. It turns out, however, that a Speaker from the GOP minority was never really a possibility, as any Republican candidate would need the votes of multiple Democrats. The rules for the election of the Speaker of the House don’t recognize the two-party duopoly. In other words, unlike the presidential contests where we are habituated to, this was not a lesser evil election, but a contest to see which candidate—no matter their party—could earn a majority of votes in the House. No Speaker would be elected unless and until someone could get that majority, and it was never likely to be a Republican. Pelosi getting fewer votes does not translate into GOP leader Kevin McCarthy getting closer to a majority of House members. Second, AOC assumed that Pelosi would say no. This in itself says a lot about Nancy Pelosi and what House progressives think of her. If they deemed Pelosi worth voting for in the first place, wouldn’t it be possible that she would at least entertain the idea of a floor vote on Medicare for All to shore up the support she needs to be elected Speaker again? Conversely if you are confident that should would sacrifice her Speakership just to ensure that Medicare for All did not get a floor vote—as AOC implied in her tweets—how could she possibly be worth supporting? If that is your expectation of Pelosi’s response, then the sensible move is to vote against her, not for her. AOC’s using the fact that Pelosi would never allow a floor vote on Medicare for All as a reason to vote for her is an astonishing feat of intellectual gymnastics. Third, AOC assumed that, should Pelosi say no, the House progressives who withheld their votes will be responsible for her losing her Speakership. And here again we see the logic of inverted democracy: when subordinates refrain from supporting a leader, the leader is not deemed to have failed her supporters, but vice versa. If Pelosi loses her position as Speaker it will not be because of such a simple demand being made by House progressives, but rather because of her refusal to concede to that demand. Pelosi losing the Speakership would be what it looks like when a constituency holds its leadership accountable. Pelosi would have failed, not the progressives who held her up to such a minimal standard. So, AOC’s argument was based on false assumptions: a Republican speaker was never a real possibility, Nancy Pelosi probably would not have sacrificed her Speakership just to prevent a floor vote on Medicare for All, and if she had, it would have been her own fault, not the fault of those who refused to support her without such a promise. But even if AOC and other progressives realized all of this, there were plenty of reasons to support Pelosi, even if they aren’t the most noble of reasons. It just so happens that Pelosi wields enormous fundraising power, as one of the richest and most well-connected (read: corrupt) members of Congress, and such informal powers, combined with the Speaker’s ability to mete out punishments and rewards in the form of committee assignments, have allowed her to scare anyone away from stepping forward as an alternative candidate from within the Democratic caucus—including the most vocal progressives in “the squad”, like Ocasio-Cortez herself. In the absence of such a challenger, the choice appeared to be between Pelosi or someone possibly even worse. So, for House progressives, it was either Pelosi or the wrath of Pelosi. When presented with such a restricted choice, there is no power—no freedom—in choosing either A or B. One must have the power to say no. The power to say no is central to the most basic democratic processes. Imagine a legislature that, when voting on legislation, structures the decision as follows: vote for bill A or bill B, and if you don’t like either, you should vote for the one you dislike less. When Congress—or any legislative body, for that matter—passes legislation, it does not use this model, but instead votes on a single bill, up or down, yea or nay. No is always an option. If no is not an option in the choice you have before you, your vote is not an exercise of sovereignty. In such cases, that sovereignty has already been exercised by whoever put the choice in front of you. Third-party voters (and many abstainers) are those who have come to grips with their power to say no. No, this choice is not good enough. No, I will not be coopted into validating the corrupt elite processes that put these oligarchic puppets on the ballot. Because of the Democrats’ reduced majority in the House, a handful of progressives had the rare opportunity to exercise their power to say no to Nancy Pelosi in order to force a vote on Medicare for All in the midst of a deadly pandemic. If Pelosi had refused to accede to their demand for a vote (only a vote!) and lost the speakership, then she would only have proved beyond a doubt that it is indeed time for new leadership. Yes, it would have been confrontational, even adversarial—it would have been playing hardball. But the power of the vote is that it must be earned, and leaders will not be made to earn your vote unless you are willing to walk away. There is no other way politicians can be held accountable to the people: if we are to have sovereignty, we must be capable of saying no. Citations [i] See, e.g. Hobbes’ Leviathan, Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, and Rousseau’s The Social Contract. Benjamin Franklin boiled it down like this: “In free governments, the rulers are the servants and the people their superiors and sovereigns.” Ralph Ketchum, ed., 2003, The Political Thought of Benjamin Franklin, Hackett Publishing, p. 398. [ii] All of the members of “the squad” ended up voting for Pelosi without extracting any promises on a vote for Medicare for All.” About the Author:

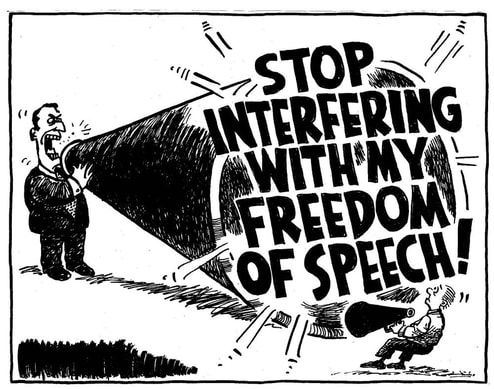

Ben Darr teaches politics and international studies at Loras College, in Dubuque, Iowa. He went to college at Northwestern College in Orange City, Iowa, and earned his Ph.D. in political science at the University of Iowa. His interests include global inequality, and U.S. foreign policy. He is currently working on a book on spectator sports as a model of neoliberal politics. When considering the philosophy of Karl Marx, one must consider first and foremost the role of alienation. The fundamental problem with capitalism is that it alienates the worker from the product of their labor. Marx developed this idea after developing his thoughts on the forms of alienation produced by religion. While the details of this transformation are beyond the scope of this paper, I highly recommend Why Read Marx Today? This work, written by contemporary philosopher and former professor of philosophy at University College London, Jonathan Wolff, concisely sketches the development of Marx’s thoughts on alienation as a product of religion to alienation as a product of capitalism. We may regard alienation as an evil precisely because it denies the human being the fruits of the most fundamental part of our nature; viz., alienation robs us of the full value of our creative faculties. The human being is inherently creative. Even so-called “uncreative” people are in fact extremely creative. Every day we create something—whether it be food, a planned experience with a loved one, or an especially clever email to a boss. Creativity should not be understood as a characteristic only attributable to the likes of Chopin and Tchaikovsky, or Van Gogh and Picasso. The creative force is the driving force of humanity, and this is precisely why the alienation from the fruits of our labor by capitalism is so insidious. Furthermore, any labor that creates value is a creative behavior. Acknowledging the theory of surplus value developed by Marx, we can recognize that the expropriation of the product of the mass’s labors is the expropriation of the driving force of their existence. One of the great beauties of humanity is our ability to create meaning itself. Could it be that the more general drive to create new means of interacting with the world is also what forces the conscious development of meaning in our lives? After all, it is the development of technology which allowed for historical human civilizations to evolve in the first place. Directly through the development of new means of production does history march. As humanity moves through new phases of development, we are forced to develop new types of meaning in order to justify to ourselves the burden of rising self-consciousness. The burden of self-consciousness is perhaps the most ancient burden in the history of human thought. One might easily interpret the Biblical story of Adam and Eve as a reflection of this manifestation of the collective subconscious. The curse of the knowledge of good and evil is the “original sin” in the broader Christian tradition, and one may quickly find the germ of truth present in material reality that is captured in this myth. By coming to self-awareness humanity has burdened itself with the knowledge of choice. It is directly our awareness of our own actions, our own ability to apply causes to the material world for a specific effect that drives our need to create meaning in our own lives. The beauty of non-human animal consciousness is that they simply cannot call into question neither their means or their ends. While it is clear non-human animals, especially other mammals, have some function akin to deliberation, it is unlikely that they are able to call into question the legitimacy of their ends. But how did we get to question the legitimacy of our ends? There is no definitive answer to this, and if there is a scientific answer to be found it will be found by anthropologists, not philosophers. However, I suspect that the development of agriculture sparked the first real questioning of the validity of our ends. While we have evidence of pre-agricultural art and artifacts, these can be seen to be largely descriptive images of the world around them. It is not until after the agricultural revolution some 12,000 (or more) years ago that clearly interpretative art began to arise. But why agriculture? The simple answer is that the development of agriculture took humanity off the well-trodden path that our evolution had theretofore plotted for us (to speak very loosely). While I can only speculate, it seems to make good intuitive sense that in shirking off the instincts given to us by direct natural selection, through the development of new technologies, our ancestors were forced to question these new ends simply in virtue of their being so new. Agriculture allowed for the emergence of the most complex social structures on earth, and, for all the evidence we have, in the entire universe. Neurological systems simply could not evolve quickly enough to keep pace with the amazing phenomenon that is cultural evolution. Forced to confront systems so foreign to the patterns of nature under which our neurological systems were developed, human beings may well have been forced to create new meaning to match the novelty of these ways of life. Perhaps meaning-making is just the natural response such highly complex brains are forced to take when confronted with such starkly different ends available to them than presented through the subconscious instinct shaped by natural selection over countless ages. It may just be the case that those humans who could not make new meaning out of their lives simply died out—or perhaps not, if we are to look at the increasing rates of suicide and depression in many industrial societies of today. “All of this is very interesting (and quite dry) but what does it have to do with free speech?” I imagine the reader is asking themselves at this point. Let us recognize that speech itself is inherently creative. In every speech act, the human being designs a meaningful construct to communicate something, however benign, to another person. In fact, we hold many of those talented in language to the highest esteem— Mary Shelley, writing Frankenstein at nineteen years of age, the greatest novel of all time, is a favorite example. As it turns out, speech is one of our most cherished creative aspects. Think back to Descartes, who ultimately appeals to an internal speech act to justify his own existence—cogito ergo sum, I think therefore I am. However, this type of thinking is just an internal speech act! While here we do not wish to defend Cartesian dualism, or really anything promoted by Descartes, the famousness of this quote of his is illuminating to just how dear our speech is to our identities as human beings. Most people greatly value the quality of their own thoughts, and the ability to express those thoughts at-least-sufficiently well through language. To take it even further, speech is largely the vehicle by which we make meaning out of our post-agricultural revolution existences. Is it not through language that we call into question good and evil? Is it not through language that we pierce through the veil of appearances with the natural sciences? Is it not through language that we express our love? Certainly not in all cases, but that is beside the point. The fact of the matter is that we do use language for these things, and even the other things we use for these purposes are fundamentally products of our creative nature, such as painting or music. We can now see the evil that is the alienation of the human being from their own speech. Certain strains of thought in the Marxist tradition are very unfriendly to the concept of free speech, but they do not realize that in doing so they are lowering themselves to the criminality of the capitalist class themselves. The aim of the liberation of the working people of the world is the end of alienation. Any Marxist theoretician who strays from the ideal of free speech forgets the vitality of the dissolution of social structures which inherently alienate individual human beings. Let us now sketch a more condensed version of our argument: 1. Alienating a human being from their creative nature is evil. 2. Alienating a human being from the products of their labor is tantamount to alienating a human being from their creative nature. 3. Speech is a product of human labor and, thereby, the human creative nature. 4. Therefore, alienating a human being from their speech is evil. 5. Censorship of speech alienates human beings from their speech. 6. Therefore, censorship is evil. The only exception to the value of free speech is speech that is directly calling for violence. As the right to life is more fundamental than even the right to the fruits of one’s labor, as life itself is that which allows for the creative force to exist, the right to freedom of speech must be subordinated to the right of people to remain safe. Speech encouraging direct violence towards persons or groups cannot and should not be tolerated, as the concern for the existential security of every person must come before any other concerns. Thus, it is acceptable to censor Nazi propaganda, for instance. However, censorship should be used with great hesitation, as censorship is one of the greatest threats to democracy as a whole. The unabashed endorsement of censorship by some in the Marxist tradition undermines the anti-hierarchical, democratic nature of the Marxist goal, and should be regarded as antithetical to the movement. About the Author:

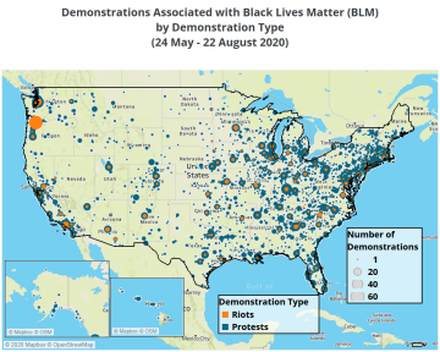

Jared Yackley is an undergraduate student of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. His primary focuses are in epistemology, history, and political philosophy. Yackley hopes to apply the principles of dialectical materialism to contemporary issues, both philosophical and political. In the days after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer in the United States, massive revolts spawned in that country and have travelled fast around the world, getting the center of international attention and gaining massive support. Among those who comment on these events, there has been much (and certainly, there has to be) insistence on the fact Floyd’s murder is not merely an isolated act of racist hatred: it is recognized that racist violence is a systemic or structural issue[1]. Nonetheless, it is very important to clarify what that means. What is that system in which racial violence is framed (inside and outside of the United States)? If this is not explained, pointing out the structurality of racist violence remains at a level of generality in which, without being less true, it ends up being something banal. Of course, I do not pretend to provide an exhaustive analysis or a definitive answer here. I would like to insist, however, that it is crucial for this explanation to understand that, like all phenomena in our society, racism is a historical phenomenon, and a specifically modern one[2]. It is a mistake to believe that it has been present exactly as we know it in all societies; yes, there has always been a difference between one’s own group and foreigners, along with a hierarchy of value between “them” (barbarians) and “us” (civilized), which can include differences based on physical or phenotypic traits. However, racism, the idea that there is a natural fatality, race, that is much more deeply rooted in the being of individuals than any archaic caste, and that innately entails a state of moral, cultural and intellectual inferiority and a servile condition, is a legacy of modern colonialism and the system of slavery that it inaugurates[3]. One must also understand that, contrary to what many liberal advocates of Western civilization maintain, slavery was not some “pre-modern” heritage. Slavery in Europe had been abolished in the 13th century, and in the Islamic world even earlier. Slavery will resurface in the middle of the 16th century, when it is already crystal clear for the whole of society that it is something aberrant, and in a much more degrading way than in any other time in history (a slave in the Middle Ages or in the Ancient World did not inherit his condition by the color of her skin, and she had a much better chance of buying her freedom for herself or her family, and even of moving up socially), because of the interests of the new merchant class that was then beginning to emerge (that is: due to the economic need of cheap labor)[4]. Racism does not precedes slavery: racism emerges after decades of forced servitude, subject to the need for profit of the new capitalist class, to its need to appropriate land and human beings to generate wealth without cost overruns. It is the quasi-natural justification of the situation of oppression inherent to a system of expropriation and exploitation. The history of modern racism and colonialism goes hand in hand with the history of capitalism: they are the same history. That is why it is a mistake to think that capitalism is merely “an economic system”. Capitalism is, above all, a system of domination based on expropriation and exploitation. And that is also why, although it is correct to celebrate the awareness of the masses who, exercising their legitimate right to disobedience, unleash their indignation and furious protest[5], we must not remain complacent in the pure celebration of revolt (which without organization and a clear strategic route, always ends up fading away). Eliminating racist structural violence, overcoming the oppression of peoples of colonial origin and exploited labor throughout the world, requires thinking about a radical reorganization of the economic and political system that we call capitalism (to think, without fear, in its opposite). We must think and speak without fear of socialism, and think and speak without fear about how we must organize to overthrow the social class that to this day benefits from the most savage injustice. Regarding this reflection, I believe that Marxism (with 180 years of theoretical and practical experience in Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas) has much to contribute. Citations [1] In the case of the United States, this becomes evident to those who contemplate the figures and the systematicity with which the Afro-descendant population suffers this kind of violence by the punitive institutions of the state. In the case of Peru (my country), a similar argument could be made in relation to the mestizo and indigenous population. [2] See Allen, T., The Invention of the White Race (2012). Also, I. Wallerstein and A. Quijano, “América como concepto o América en el moderno sistema mundo”, in Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales vol. XLIV n°4, 1992. [3] See Losurdo, D., Class Struggle: A Political and Philosophical History (2015). [4] Indeed, it is interesting to see how European society, in the centuries before the restoration of the slave trade, had already generated institutions and normative resources to question the practice of slavery (the antislavery position of the theorist of absolute monarchy Jean Bodin can be contrasted with that of the “father of liberalism”, John Locke, whose defense of private property included a defense of slave ownership in the colonies). The Catholic Church and the monarchical state, despite all of their despotism, often played a positive role in this regard. It was against the “illegitimate” interference of these “illiberal”, pre-modern powers in regard to the administration of their possessions that liberalism as a doctrine would be born. See D. Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counter-History (2005), and for a more general history of “primitive accumulation”, see the first volume of Marx’s Capital. [5] See Celikates, R., “Rethinking Civil Disobedience as a Practice of Contestation – Beyond the Liberal Paradigm”, in Constellations Volume 23, n°I (2016). About the Author: Sebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Originally published in Disonancia: Portal de Debate y Crítica Social (Jun 4, 2020)

Historically, Marxism has been perceived to be inexorably hostile to religion and especially to Christianity (since Marxism grew up in the Christian West). Nowadays most non-Marxists think Marxism is hostile to all religions and looks down on those who have religious beliefs. There are others today who think Marxism has become more mellow and is either neutral about religion or even somewhat encouraging in its attitudes towards some religious opinions. I hope to show that a contemporary Marxist position will incorporate some of both these perceptions. The basic Marxist position was first enunciated by Marx as long ago as 1843 in his introduction to a "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Law." This work contains the famous "opium of the people" remark. More pithy than Lenin's "Religion is a sort of spiritual booze", which I am sure it inspired. What did Marx mean by calling religion an opiate? Being a materialist, Marx of course holds to the view that religion is ultimately man made and not something supermaterial or supernatural in origin. "Man makes religion," he says. Man, or better, humanity is not, according to Marx, some abstract entity, as he says, "encamped outside the world." In the world of the early nineteenth century the masses of people lived in horrendous societal conditions of poverty and alienation and lived lives of hopeless misery. This was also true of Lenin's time, as well as of our own for billions of people in the underdeveloped world as well as millions in the so called advanced countries. The social conditions are reflected in the human brain ("consciousness") and humans living in such conditions construct their lives according to these reflections (ideas). These social conditions and ideas give rise to forms of culture, political states, and ideas about the nature of reality and the meaning of it. Marx says, "Religion is the general theory of that world... its universal source of consolation and justification." The world we live in is one of exploitation and the human spirit or "essence" appears in a distorted and estranged form. This is all reflected in religion as if it (the human spirit or essence) had an independent existence rather than being our own self-creation out of our interactions with the terrible societal conditions in which we find ourselves. In order to improve our conditions we must struggle against the imperfect social world and the ideas we have in our heads that that world has placed there and which reinforce its hold on us. This leads Marx to say. "The struggle against religion is therefore indirectly a fight against the world of which religion is the spiritual aroma." This is the background to Marx's view of religion as an opiate. The complete quote is: "Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of spiritless conditions. It is the opium of the people." Lenin remarks that this dictum "is the corner-stone of the whole Marxist outlook on religion." (CW:15:402) Marx has more to say than this, however. It is possible to misinterpret Marx's intentions by not going beyond this dictum. Let's see what else he has to say. Remember that Marx said that struggle against religion was indirectly a fight against an unjust and exploitative world. Religion is an opiate because it produces in us Illusions about our real situation in the world, the type of world we live in, and what, if anything, we can do to change it. The struggle against religion is not just an intellectual struggle against a system of beliefs we think to be incorrect. Marxists are not secular humanists who don't see a connection between the struggle against religion and the social struggle. This is why Marx maintains that, "The demand to give up illusions about the existing state of affairs is the demand to give up a state of affairs which needs illusions." That is to say, he wants to abolish religion in order to achieve real happiness for the people instead of illusory happiness. We will see that when Marx, Engels or Lenin use the word "abolish" they do not mean that the government or any political party should use force or coercive measures against people who are religious. What they have in mind is that since, in their view, religion arises as a response to inhumane alienating conditions, the removal of these conditions will lead to the gradual dying out of religious beliefs. Of course, if the Marxist theory on the origin of religion is incorrect, then this will not happen and religion will not be abolished. At any rate, this is what Marx means when he says, "Thus the criticism of heaven turns into the criticism of the earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics." We should also keep in mind that in addition to the theory of the origin of religion, Marx, Engels and Lenin were most familiar with organized religion in its most reactionary form as a state supported church representing the most unprogressive and backward elements of the ruling classes. "Quakers", for example, does not appear as an entry in the subject index to Lenin's Collected Works. They are not thinking about religion as a positive force as we might today: as for example the Quakers in the antislavery movement or the Black church in the civil rights movement. [Although Engels had positive things to say about early Christianity in the time of the Roman Empire.] These would have appeared to them as aberrations confined to a very tiny minority of churches. Sixty six years after Marx published his remarks on religion, Lenin addressed these issues in an article called "The Attitude of the Worker's Party to Religion" (CW:15:402-413), published in the paper Proletary in 1909. In his article, Lenin categorically states that the philosophy of Marxism is based on dialectical materialism "which is absolutely atheistic and positively hostile to all religion." There is no room for prisoners here! "Marxism has always regarded," he writes, "all modern religions [he remembers Engels liked the early Christians] and churches, and each and every religious organization, as instruments of bourgeois reaction that serve to defend exploitation and to befuddle the working class." I don't think we could have that opinion today. I mentioned above the role of the Black churches in the civil rights movement and we also know of many religious organizations and churches that have been involved in the peace movement and have taken stands in favor of workers rights and other progressive causes. In dialectical terms, what in 1909 appeared as two contradictory approaches has now become, in many cases, a unity of opposites. While Lenin's comments are, I think, on the whole still correct about the role of religion, we must admit that there are now many exceptions and that Lenin would probably not formulate his views on religion in quite the same way today. Be that as it may, religion would still be seen as an illusion to overcome by a proper materialist worldview. This does not mean that Lenin would have been hostile towards people having religious beliefs. He is very clear, following Engels, that to wage war against religion would be "stupidity" and would "revive interest" in it and "prevent it from really dying out." The only way to fight religion is by basically ignoring it and simply carrying on the struggle against the modern system of exploitation (capitalism). Those so-called revolutionaries who insist on proclaiming that attacking religion is a duty of the workers' party are just engaging in "anarchistic phrase-mongering." We have to work with all types of people and organizations to build the broadest possible democratic people's coalition. Still following Engels views, Lenin says the proper slogan is that "religion is a private matter." Elsewhere he writes ["Socialism and Religion" in the paper Novaya Zhizn in 1905: CW:10:83-87], that to discriminate "among citizens on account of their religious convictions is wholly intolerable." He maintains the state should not concern itself with religion ("religious societies must have no connection with governmental authority") and that people "must be absolutely free to profess any religion" they please, including "no religion whatever" (atheism). Would that socialist states (among others), past and present, followed Lenin's philosophy on this matter. Lenin sounds positively Jeffersonian! Jefferson in his second inaugural address (1804) proclaimed, "In matters of religion, I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the constitution independent of the powers of the general government." This is in line with Jefferson's 1802 comments about the "wall of separation between church and state." And what does Lenin say? He says the "Russian Revolution must put this demand into effect"! "Complete separation of Church and State is what the socialist proletariat demands of the modern state and the modern church." However, what is true for the state and the citizen is not true for the worker's party. Religion is a private matter in relation to the state but not in relation to the party. To think otherwise, Lenin says, is a "distortion of Marxism" and an "opportunistic view." Therefore, the party must put forth its materialist philosophy and atheistic world view and not try to conceal it from view. But this propaganda "must be subordinated to its basic task-- the development of the class struggle of the exploited masses against the exploiters." This basic task also means that workers with religious views must not be excluded from joining the party, and, indeed we "must deliberately set out to recruit them." Not only do we want to recruit them as part of the work of building a mass movement and mass party, "we are absolutely opposed to giving the slightest offence to their religious convictions." People are educated in struggle not by being preached to. This means that valuable party time should not be taken with fruitless debates on religious issues, but with organizing the class struggle. Finally, Lenin says there "is freedom of opinion within the party" but this does not mean that people can use this freedom to disrupt the work of the party. So, I conclude that, outside of the realm of theory, Marxists are not hostile to religion per se and are willing and eager to work together with all types of progressive people, religious or not, who will struggle with them in the current fight against the ultra-right and in the eventual fight, of which the current struggle is a part, for the establishment of socialism. About the Author: Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. This article was originally published in 2005 by Political Affairs