|

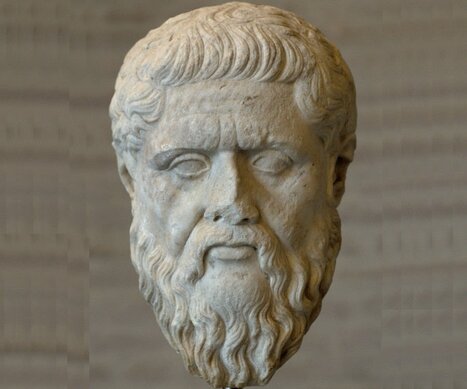

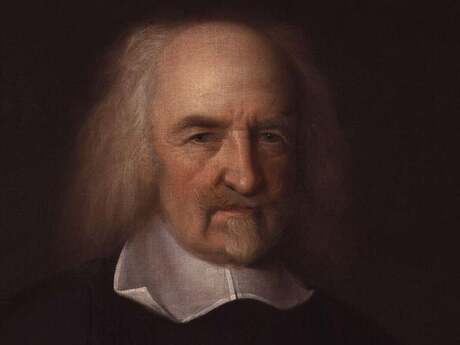

12/4/2020 Searching for Universal Justice: The Platonic Fall and its Influence in Western Philosophy. By: Carlos L. GarridoRead NowIntroduction In this paper I will examine the history of conceptualizing justice in western political thought through the lens of what I call the Platonic fall. I define the Platonic fall as the moment when thought from a very particular context is universalized in a manner that seeks to transcend, escape, and forget the contextual boundaries of the theory's establishment. The term ‘fall’ is used because what is happening is a demoting of a perspective from universal (in terms of totality) to particular. From the start, I would like to emphasize that this fall does not itself signify the theory's absolute relativity, that aspects of a theory might contain universal characteristics is accepted. Rather, the point is one about the de-classification of the theory from universal to relative/particular as a totality. I will begin by laying out the Platonic theory of justice and how it sets up this ‘fall’. Once I define this ‘fall’, I plan on extrapolating on the influence it has had in western political philosophy by looking at the theories of justice in Hobbes, Locke, and Kant. The importance of this will lay in our ability to recognize that all theory, as long as we are in class society, is an expression of a class perspective. And although this is not wrong in itself, the contradiction comes when this particular is masked as a universal. I will conclude with a summation of why the ‘fall’ happens, and with a consideration of a future where the ‘fall’ not only ceases to fall but also to exist overall. Part 1: Justice in Western Political Philosophy Plato:In the Republic Plato seeks justice as the highest of values. Justice, for Plato – at least in this text – carries two different but corresponding dimension to it. A micro dimension in the level of individual justice, and a macro dimension in the level of societal justice. In both cases, justice can be seen as a non-equilibria balance between three parts. It is thus, a tripartite conception[1], both in the individual and in the societal presentations. In the individual, the tripartite division of the soul is between the logos (reason), thymos (emotions/honor/spirit), and eros (desire/appetites). To Plato, the highest value was placed on the logos, the rational part of the soul. This is because it is this part of the soul that he believed was truly eternal. This part of the soul he conceived of as immortal and existing within the ideal forms except when it reincarnates into the material realm (which he conceived of as a shallow representation of the ideal world).[2] Given the superiority of this part of the soul – a result of its intimate relation with the realm of the forms – Plato considered that this is the part of the soul that should control the other parts. In Plato’s micro assessment of justice, what we find is justice as the ability of the rational aspect of the soul to virtuously control the appetitive and the spiritual parts. This control itself must be one that is balanced. A tyranny of reason itself could cause unbalance and lead to injustice. Thus, we must consider the rational part of the soul as the driver in a horse chariot[3]. The driver is one guiding and controlling the other two. The driver is not the sole participant, he recognizes the role the two frontal horse play in his development (movement). Thus, it is not a forceful rule of the rational part, but a controlled guidance of the rational part, with the goal of using the other two parts in a way that lets the subject as a totality advance. The other extreme of this would be a lack of control from the rational part. This would mean the domination of the rational part by the emotional/spiritual or appetitive aspects. This is where unfreedom arises; when one is unable to control one’s own appetites and emotions. Thus, to Plato, individual justice consists of being able to rationally control one’s emotional and appetitive parts. The concept of justice in society is a mirror of justice in the individual. Society, like the individual soul, is divided between groups that are guided by emotions, groups that are guided by appetites, and groups that are guided by reason. To Plato, the groups that are guided by appetites are the lower classes, those being the workers. The group guided by emotions – like honor – are the warriors, which he calls the auxiliaries. Finally, those who are guided by reason in society are the guardians – an intellectual elite class – which would be headed by his philosopher king. Like in the case of the individual soul, justice in the society consist of being able to have a successful balance where all the classes play their respected parts in society. The guardians – representatives of reason – guide the community, the auxiliaries – representatives of honor – obey and enforce the guidance of the guardians, and the workers/producers do pretty much what they are told to do by the guardians; which is to produce for the general populace. If all goes well, the auxiliaries will be inactive, because their role as the forceful enforcer of the guardians will upon the producers will be deactivated with the producers consent to the orders of the guardians. Thus, in Plato, we have already the function of what is called a noble lie. A noble lie – as contradictory as it may sound – is given an essential role in the process of establishing and maintaining a just society[4]. Plato's FallAlthough Plato might have made it down safely in the flight of stairs of the school of Athens, his conception of justice will suffer a different fate. Plato portrays his conception of justice as a universal. His engagement with justice is not one which seeks to understand justice in relation to a certain spatial-temporal context, but one which seeks to understand justice outside of its being in a particular circumstance. His understanding – or attempt at theorizing – justice is as universal justice. This is a justice that is conceived as true in all places at all times. Not only is his conception of justice aiming at a universality, but the foundation upon which it is built is itself based on the universality of the realm of the forms. Thus, with Plato – and we will see how this trend infests the history of western philosophy – justice is something that must be thought of as universal. Justice must be the same – at least in its general foundation – everywhere and always. The question is, can Plato really do that? Can Plato escape the biases of his time, and specifically the biases of his placement-in-society at his time? Or is his attempt to escape the confounds of his historical and cultural specificity really just an illumination of the ideals of his historical and cultural specificity? Now, I expect a well-read reader can respond with the question “How is Plato expressing an ideal reflection of his time, if he is himself placed at odds with his own time?”. What this question asks is, if Plato stood against most of the regular held beliefs of his time, how can his philosophy, and more specifically, his theorizing of justice, be one that is limited by the confounds of a society he was himself not in favor of? If for example, Greek society at his time placed a high value on democracy, and Plato repeatedly stands against democracy, how can his thought be pinned down to a time and location with which he was so profoundly at odds with? The answer is simple, the ideas of a time are not homogenous. For every place there is a ruling hegemony, there is always a counter hegemony, although more or less controlled and influenced by that which it is counter to. This is how Plato represents a reflection of his time. He is the intellectual counter hegemony present in Greece. And though he might not reflect the dominant attitude of his time (good philosophers rarely do), he is still bound within the confines of matter while claiming to be lounging in spirit. What I mean by this is that Plato’s fall is in his conception of justice presenting itself as a universal form of justice, while in reality being a very acute conception of justice limited by the confounds of his class position in his spatial-temporal context. Plato’s anti-democratic sentiment – which is the negativity present in his affirmative theory of justice – is not derived from a void; but rather; is a very specific illumination caused by his concrete experience of the horror democracy was able to do to his beloved teacher , Socrates. His rejection of democracy leads to his affirmation of an intellectual elite conception of a just society. The one cannot be separated from the other. And although we might be able to see ascribed in his overall project on justice elements of truth that still linger today, the project’s overall presentation as universal, and its concrete observation as contextual, establishes a trend in western philosophy. The trend is led by an appeal to universals that are hyper exaggerated phantoms of the given philosopher’s concrete class position within their respective historical context. Part 2: Plato the Trend Setter and the Disciples of the FallIn the same manner in which today’s celebrity trends end up being followed by us the peasants, Plato stands as the ultimate demiurge celebrity figure in the history of philosophy. The ultimate trend setter. His good aspects, and bad ones, are all seen reflected in different ways in the history of western political philosophy. In this manner, Whitehead is truly correct in his famous dictum “the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consist of a series of footnotes to Plato”.[5] What I hope to demonstrate in this section, is how three of the most prominent political philosophers in the history of western philosophy have the same fall previously mentioned in Plato. Thus, who we will be concretely looking at is Hobbes, Locke, and Kant. Hobbes:An informed reader might ask, why Hobbes? If Plato’s fall is in the fact that he expresses what is a concrete particular as a totalizing universal, this fall must not be in the great materialist thinker, whose feet were grounded enough to not believe any silly conception of transcendence. This great materialist, who is aware that “man is a living creature”[6], who unlike Plato’s man, has a rational side that is there to serve the appetites (the horse driver is the one pulling the horses in the chariot now), can surely not have the same faults of his idealist predecessor. Well, I will argue that within the confines of Hobbes’ depersonalized materialist relativity, we find an implicit appeal – or better yet, assumption – of a present universality. What is this assumed universality? Nothing if not the whole basis for his social contract theory, the indubitably existing universal fact of contractual relations. This is, of course, the holy covenant! The one whose holiness saves us from the ‘state of war’ of which our natural state consist of; whose man is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”.[7] This Holy covenant which drives people to ‘give-up’ certain rights for the security of civil society and the state is where we find the assumed universality. Hobbes’ theory of justice is tightly related to this contractual framework. What is just is the keeping of covenants, what is unjust is its breaking. A state of constant covenant breaking (the time before the establishment of the state) is the necessary unjust predecessor of the just. The just can only arise thanks to the unjust. It is a direct inversion of the biblical formula of the devil’s turning against God. For evil (the devil) to arise, the good of God must have been present as that which one deviates from. For Hobbes, the great materialist, we have the same formula but on its head, only after the evils of the injustice of covenant breaking can the good and just activities of covenant keeping (or monitoring by form of a state) arise. Justice is thus the keeping of covenants, and injustice the breaking of covenants. The content of the covenants might be admittingly relative, but the covenant itself is a universal truth of a post ‘state of war’ humanity. This fetishism of contractual relations, which sees the contract as the universal foundation of justice in civilized society, is where we see Plato’s trendy fall present in Hobbes. The contract, and its treatment as universal, is itself a particular reality of the transition into bourgeois society. Oh the holy covenant, the holy father of bourgeois society’s trinity. The one whose holy presence the process of enclosure depended on. What a great universal. Whose holy justness we are to thank for expropriation of lands, exploitation of labor, and enslavements of bodies. Oh this holy covenant upon which bourgeois society till this day revolves. This magnificent freedom to be unfree. This is Hobbes’ kernel of universal justice. One whose’ describing as universal is a sin against history, and whose’ describing as just is a sin against humanity and nature. Hobbes’ justice – the keeping of the universal system of covenants – represents the myth of capitalism’s freedom. You are free to engage in a relation of exploitation or die! What a universally just dichotomy! Oh the beauty of choice and freedom in bourgeois society! Locke:Continuing with our analogy of the holy trinity of bourgeois society, if Hobbes’ covenant was the holy father, Locke’s unbreakable bond of justice and property under the universal guise of natural law is the holy spirit. Locke’s conception of justice is tied to the gifts of land property God has given to humanity in common.[8] This is a gift which can only help in satisfying our needs through our own laborious relation to it.[9] The laboring of the land, and the fruits it bears, is the source of property. As he states, “He that is nourished by the acorns he picked up under an oak, or the apples he gathered from the trees in the wood, has certainly appropriated them to himself.”[10] Thus far, we have a conception of our natural right to property, and property is seen as the fruits of the labor which we have incorporated on the land that is gifted to us collectively by God. Where can we see justice here? In the spoils. He states, “But how far has he (God) given it (land) to us? To enjoy. As much as anyone can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labour fix a property in: whatever is beyond this, is more than his fair share, and belongs to others. Nothing was made by God for man to spoil or destroy.”[11] Jesus Christ Johny Locke, you sound like a socialist! If only he who works today received the equivalent of what they produced (and not just enough to go home and subsist), and if only the constant spoilage of unsold goods were seen as an injustice in a world where there are still so many facing necessities that are solvable by those same goods being spoiled, perhaps the world would be a more just place. But let’s hold on to our horses, with the exception of Locke’s right to revolution in Ch. XIX of his Second Treatise of Government, his radicalism in relation to labor and property ends quickly. Soon we see that those natural rights, only belong to natural human beings. Thus, in his talk of the “vacant places in America”[12] we saw that the being with the right to property is a specific kind of being, a white being. The native savage is excluded, what a holy spirit this justice represents! But wait, there’s more! Locke finds a loophole for the spoilage law that limits our right to property. This loophole is money! He says, “this invention of money gave them the opportunity to continue and enlarge them (possessions)”.[13] Thus, money comes in as the un-spoiling possession. But we must think of this critically and go beyond money itself. This level of the beyond, that delves in the realm of property that does not spoil, is capital. What a wonderful invention, a possession that not only does not rot, but on the contrary, continuously reproduces itself. Capital, whose life is constantly rejuvenated by the slow deaths of those who rejuvenate it! Here we see that although Locke’s initial positioning might seem radical, it transforms very quickly into what is perhaps the most influential of the early philosophical justifications for the development of capitalism. The man whose conception of justice is inextricably tied to the universal natural right of property is neither universal nor just. It suffers the Platonic fall of universalizing the particular spirit of the epoch (specifically from the up and coming bourgeois class). As with Hobbes, considering this doctrine universal is a crime against history, and considering it just – a doctrine so tied to the global pillage of lands and bodies in capitalist expansion – is a crime against humanity. Even his declarations of the rights to revolution, whose radicalism was truly ahead of its time and was one of the most overwhelming inspirations for our project as a nation, is itself not a universal right at all, but the right for the political emancipation of the bourgeois class from the clamps of the privileged aristocracies. Kant:Finally, the last third of the trinity! If Hobbes’ universal covenant was the holy Father, and Locke’s universal right to private property and accumulation was the holy Spirit, in Kant’s rational moral agent – capitalism’s monadic individual – we have the holy Son. To Kant, justice is inseparable from the duties we have to other people as moral agents. These duties, arise from his categorical imperative which states that “act as if thy maxim were to become by thy will a universal law of nature”[14] and “act as to treat humanity, whether in thine own person or in that of any other, in every case as an end withal, never as means only”[15] This is perhaps a bit harder to see its particularity to a class interest, especially considering the extent of the influence it has had on socialists – as the representatives of the interest of the proletarians – around the world, while at the same time reigning as one of the dominant perspective in the halls of bourgeois society. But we must remember that this is a Kant influenced by Rousseau’s freedom as collective autonomy, and thus we must measure his position with that of the most advanced (in terms of escaping a concept of justice from a ruling class position) in his time. What we find when we do this is that his concept of justice is a step backwards (in terms of the larger picture) from the approach of Rousseau. The latter’s justice, as well as his conception of freedom, sprung from a sensation of a collective sovereignty. It represented a thought impregnated with a post-bourgeois ethos. The bourgeois ethos is the holy Son, the monadic individual separated from nature, community, and even his own body (Cartesian res extensa and res cogitans). The bourgeois ethos prioritizes this ego that floats on top of the world and looks down on it as other and lesser. Rousseau begins the process of demystifying this ego and placing it in community. Kant returns to the bourgeois individual, albeit now with duties to the other (of course the white other), but it is a return that generally aligns itself with the spirit of individualism in bourgeois society. As such, it is still an acclaimed universal justice (based on the duties that arise from the categorical imperative) that is tied to a necessary particular class in a particular epoch. But even if we are charitable with Kant, and admit the class fluidity of his theory, the fluidity is not enough to consider it a universal totalizing truth, given that its depiction of justice is within the capitalist lebenswelt (life-world), and has as its foundational element the holy Son, capitalism's monadic reified human. ConclusionIn conclusion, what we have found here is that the history of western political philosophy is plagued by the original Platonic sin of universalizing theories that stem, and are necessarily tied to, particular spatio-temporal contexts. This is a sin whose presence has been felt in even the most staunchly materialist thinkers the west has produced. Through the analysis of Plato, we established the genesis of what becomes a central trend in western philosophy. Through our analysis of Hobbes, Locke, and Kant, we have materialized our conclusions of Plato’s trend, by showing that whether in their outright conceptualizing of justice as a universality, or in their hidden universal assumptions behind their ‘relative’ theory of justice, the history of the greatest thinkers in western philosophy is synonymous with the history of the greatest thinkers of the ruling classes of certain epochs. What I have hoped to prove here is that all philosophizing in general, and philosophizing of justice in particular, is always philosophizing from a class position. A class positions that we may certainly attempt to abandon, but one whose leap out of will necessarily land us in another class position within the existing class structures of society. Thus, you can have an Engels whose class position is bourgeois, but whose class thought is proletarian. Just like you can have a Marx whose class position is petty/bourgeois and intelligentsia, but whose class thought is proletarian. In class society, all thought is class thought. This is something that only those who represent the proletarian class – or more generally the working mass – seem to understand. This is not to say that there aren’t advancements in the process of discovering universal truths about justice. There definitely can be. Rather, what I am attempting to say is that a universalizing and totalizing way of thinking about justice that stems from a class society will always be merely the justice of the class the author identifies and thinks from. Universal justice can only become a totalizing cognitive reality when justice loses its class chains. Which is to say, only in a classless society can universal justice be conceived of. Only then, can the perspective of the thinker be a truly human perspective, and not just a class perspective. Therefor, only then can a theory of justice that includes all be possible. The paradox is: given that our theorizing of justice necessarily stems from the presence of injustice, a truly universal theorizing of justice will become impossible in the same instance in which it becomes possible. When it is possible to speak of universal justice in a classless society, we will lack the language to speak of the affirmative (justice), because we would be missing from experience its necessary negation (injustice). Thus, justice is in a dialectical position of never fully being or not-being, but always becoming. When justice can be thought of in its full being, not only would such task not be necessary, but it would be linguistically impossible because of our inability to question ourselves about justice in a state where there is no injustice. Citations [1] In Book IV we see the realization that there must be at least two parts in the soul. From here on the tripartite conception develops. Plato. (2004) Book 4. In Republic (pp. 116-148) Barnes & Nobles Classics [2] Book 3. Republic [3] Plato. (370 B.C.). Phaedrus. Retrieved from https://freeditorial.com/en/books/phaedrus/related-books [4] Book 3. Republic [5] A.N Whitehead on Plato. Retrieved from Columbia College Website: https://www.college.columbia.edu/core/content/whitehead-plato [6] Hobbes, T. (2008). Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil. Touchstone. (pp. 24). [7] Ibid., (pp. 110). [8] Locke, J. (1980). Second Treatise of Government. Hackett Publishing Company. (pp. 18-19). [9] Ibid. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid., (pp. 20-21) [12] Ibid., (pp. 23) [13] Ibid. (pp. 29) [14] Kant, I. (2001) Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals. In Basic Writings of Kant. (pp. 179) Modern Library [15] Ibid., (pp. 186) About the Author:

My name is Carlos and I am a Cuban-American Marxist. I graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Loras College and am currently a graduate student and Teachers Assistant in Philosophy at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. My area of specialization is Marxist Philosophy. My current research interest is in the history of American radical thought, and examining how philosophy can play a revolutionary role . I also run the philosophy YouTube channel Tu Esquina Filosofica and organized for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020.

1 Comment

JR Williams

12/4/2020 12:37:40 pm

What an insightful essay. I’d like to see more of these philosophical works! Well done.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed