|

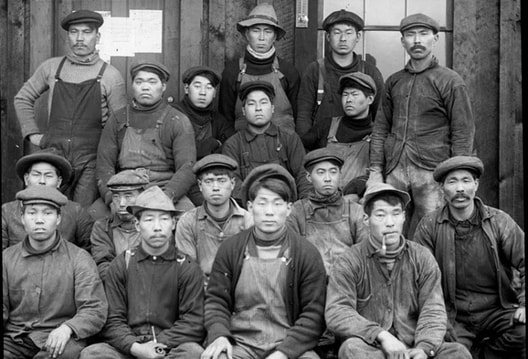

In my last essay, I discussed how capitalist hegemons have used their control over food supply to shape rules of international commerce. I also demonstrated how these policies have led to economic shocks and displacement in developing countries, leading to mass migration in search of economic opportunity. I believe this history is essential to understand the migration that has been a focal point of American and European politics in recent years. In this essay, I will attempt to explore the issue of migration in capitalist development, hoping to provide historical context for our current conceptions and policies around immigration. One of Marx and Engels's favorite examples was that of the Irish. Up until the mid-19th century, Irish society was structured around a system of tenant farming with most of the land owned by English and Anglo-Irish families. This landed gentry introduced the potato to Ireland in the mid-1700s as a subsistence crop for the rural poor; by the 1840s it had become the staple crop of Ireland with much of the population nearly completely dependent on the potato for their diet. Thus, when the potato blight hit in 1845, the Irish were left with little to eat, even though they were still exporting various agricultural commodities to England. During and after the famine, the British aristocracy took the opportunity to push small-landholders off their land.[1] As Marx put it, "If any property it ever was true that it was robbery, it is literally true of the property of the British aristocracy. Robbery of Church property, robbery of commons, fraudulous [sic] transformation accompanied by murder, of feudal and patriarchal property into private property."[2] The result was the death of nearly 1 million Irish and the additional emigration of 1 million more. Thousands of these newly-landless Irish, migrated to English cities seeking any form of economic opportunity.[3] As I pointed out in my last essay, this sudden influx of workers allowed British capitalists to supplement their industrial reserve army with an injection of a subordinate group to perform degraded labor, intensifying competition in the labor market and driving down wages. Stoked by members of the bourgeoisie to divide the working class, anti-Irish sentiment spread rapidly across England, with violent attacks against Irish migrants becoming commonplace. This stance is probably best exemplified by Benjamin Disraeli who wrote in 1836: "[The Irish] hate our order, our civilization, our enterprising industry, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain and superstitious race have no sympathy with the English character. Their ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry. Their history describes an unbroken circle of bigotry and blood."[4] These same tropes have often been repeated in different ways and we have seen them reappear in modern American political discourse in recent years. Though billed as a "Land of Immigrants" in the modern liberal lexicon, the actual history of migration in America is much more muddied than this simple platitude indicates. As Aziz Rana put it: "Throughout American history, the tension between capitalism and both democratic self-government and economic independence has largely been resolved by native expropriation and/or racialized economic subordination."[5] From its inception the United States has been an experiment in what Rana and others refer to as "settler colonialism". Despite the proclamations of politicians extolling the American virtues of acceptance and equal opportunity, race and class have structured American societies from the earliest days of the Jamestown colony. During the early colonial period, British officials considered America a depository for their “excess” population, i.e. the poor. To encourage this “rubbish” to migrate to the “New World” the British government created a system of land-grants promising fifty acres to those who made the journey. At first, this helped promote equitable land distribution, but, with the establishment of the “headright system” in 1618, land was allotted based on the number of people whose travel expenses a settler paid for, granting fifty additional acres per head. This incentive, mixed with the large expense of the journey, led to the broad use of indentured servitude, with many of the early settlers coming to America via this arrangement.[6] Importantly, the additional land was given whether the servant survived their indenture or not- leading to extremely exploitative labor conditions. Obviously, this system of allocation led to a vastly unequal distribution of land with much of the best land accruing to the wealthy and politically connected. Eventually, most of the small farmers were squeezed out of the market resulting in a mass amount of landless poor who would become “squatters” in peripheral areas clearing land for subsistence farming. As formal British settlements expanded to these peripheral areas, squatters, who held no formal title to the land they cleared, were again pushed off their land repeating the process. Thus, it is no surprise that several founders, such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, saw western expansion as a necessary safety valve for excess population. This became a major point of contention between the colonists and the British following the acquisition of French territory in North America after the Seven Years’ War.[7] After signing the Treaty of Paris, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding all settlement in territory west of the Appalachian Mountains and designating this area as an “Indian Reserve”.[8] Not only did this limit western expansion, but many also feared having native civilizations so near British settlements. This is reflected in the Declaration of Independence where Jefferson accused England of having “endeavoured [sic] to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction of all Ages, Sexes, and Conditions.”[9] This statement is indicative of how the American project was conceived. From the earliest days of colonization American leaders have sought to manipulate the demographics of the growing nation, shaping who would be allotted full citizenship and who would not. With the addition of vast new western territories, via the Northwest Ordinance and the Louisiana Purchase, and the expansion of American industry, the young nation required new sources of immigrant labor to fuel western expansion and development. Thus, many early American capitalists supported broadly open immigration policies, with 33 million immigrants entering the U.S. between 1820 and 1920. Indeed, during much of the 19th century American industry was dependent on foreign labor with first- and second-generation immigrants constituting 57 percent of manufacturing[10] and 64 percent of mining laborers by the 1880s.[11] But before we wax poetic about America’s tradition of acceptance, we need to remember that this openness has always been qualified. As Suzy Lee argues: “Capitalists may prefer the opening of borders to the extent that immigration policy permits large flows of immigrant labor, but they also prefer an immigration system that does not confer many rights to these entrants.”[12] Essentially, business interests want to ensure a constant supply of disenfranchised workers who would then be forced into subordinated forms of labor. Traditionally, this subordinate labor had been supplied by natives, indentured servants, and African slaves; but, with the abolition of these variations of bonded servitude, a new system would need to be devised to serve the same function. In the 1860s, the federal government created the “United States Emigrant Office” to promote immigration and legalized the use of contract migration which was ultimately very similar to indentured servitude.[13] These policies were designed to attract migrants from Europe and Asia to work in eastern factories or, as was most common for the Chinese, to develop the west.[14] Between the years 1849 and 1880 the population of Chinese immigrants in the U.S. had grown from 650 to over 300,000.[15] Of course, this massive influx of Chinese people was accompanied by laws intended to ensure their status as a subordinated group, such as placing exorbitant taxes on foreign-born miners.[16] Importantly, Chinese immigrants were excluded from the Naturalization Act of 1870 which only extended citizenship rights to formerly enslaved black people, which also allowed many Western states to pass Alien Land Laws prohibiting “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from acquiring land.[17] Further, we see the U.S. system of deportation emerge with the passage of the Paige Act in 1875, which mainly targeted Asian women for deportation. This Nativist backlash to Chinese immigration was more direct in the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882, which placed a ten-year moratorium on all Chinese labor immigration and forbade any state from extending citizenship to Chinese resident aliens. Ten-years later, the Geary Act passed extending Chinese exclusion as well as requiring Chinese people to register and obtain a certificate of residence, without which they would be subject to deportation. The Geary Act was made permanent in 1902 and shaped immigration policy for the early decades of the 20th century.[18] The anti-Chinese sentiment of the time is reflected in Justice Harlan’s much celebrated dissent in the Supreme Court Case, Plessy v. Ferguson, where the justice proclaims: “There is a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race.”[19] Here we also see a notable shift in government policy towards “closing the gates”, made possible by the scarcity of remaining unsettled western land and growing mechanization in American industry, producing a domestic labor surplus and decreasing demand for immigrant labor. This change in policy was consolidated by the Quota Acts of the 1920s establishing a racialized quota system meant to favor immigration from European nations as well as creating systems of visas and deportation. However, certain industries, such as agriculture in western states, still depended on immigrant labor, leading Congress to exclude immigration from Mexican and other Latin American countries from the Quota Acts. These restrictions on immigration and the severity of enforcement would fluctuate depending on the labor needs of business. As Aziz Rana summarizes: “Most of the 20th century is state and corporate actors keeping the border fluid to ensure pliable labor supply from Mexico, then subjecting them to extreme forms of coercive violence in the U.S. when businesses view their labor as unnecessary.”[20] In the 1950s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS, precursor to ICE), campaigned to shift Mexican immigration flows away from unauthorized migration into formal channels such as the Bracero guest-worker program. This also provides us another example of early deportation systems, with the INS’s Operation Wetback, which involved the mass detainment of undocumented immigrants and immediately placing them in the formal guest-worker program.[21] The Bracero program, along with racial quotas and western-hemisphere exclusion were ended in the 1960s after a mass movement of organized labor and insurgent farmworkers successfully pressured policymakers. This temporarily weakened companies dependent on immigrant labor, but, eventually, this was compensated for by a reversion of immigration flows into undocumented channels, accompanied by the explosion of “undocumented” status for Mexican immigrants.[22] In the decades since the 1960s, Congress has passed various legislation attempting to increase border security and restrict unauthorized immigration to no avail. Border enforcement only captures approximately one-third of migrants attempting to cross and those who are not captured are more likely to remain instead of migrating seasonally. The result is an estimated population of 11 million undocumented immigrants residing in the U.S. effectively serving as a guest-worker program. To understand this shift in immigration policy we must also analyze the structure and effects of the neoliberal global order which has developed in recent decades. Aziz Rana describes it as: “The story about the profound global iniquities hard written into the international order, from which the U.S. gains the most benefit. The U.S. has constructed international legal arrangements that allows its capital to flow anywhere, while controlling immigration.”[23] As I described in my last essay, developed western nations, through control of food supply and global organizations such as the IMF and WTO, forced developing nations to undergo a process of economic restructuring, opening domestic markets to foreign commodities and investment. Thus, neoliberal policies, by destroying domestic industries and displacing mass amounts of people, have ensured an overwhelming surplus population used as a source of cheap labor. This is made possible by the concentration of capital into fewer, larger, transnational companies who can use this cheap labor to outsource parts of the production process to developing nations, leading to the “configuration of enclave economies operating as appendages in global commodity chains.”[24] Currently, between 55 and 66 million people in the southern hemisphere work in these types of enclaves. Corresponding with these neoliberal reforms in developing nations has been the restructuring of industrial relations in developed countries weakening labor-rights and expanding employer control. For companies this has meant greater discretion in wage determination, work organization, and decisions over hiring-and-firing. For the working class this has meant decreased job security, intensification of work, and stagnation of wages. In broader economic terms it has meant the expansion of differentiation and precarious employment in the global division of labor, devaluing the cost of labor and lowering wages. Precarious employment “is a type of employment that is unstable, insecure, and revocable.”[25] Currently, in the United States the percentage of workers employed part-time and under non-standard labor relations were around 17% and 10%, respectively, with over 1.5 billion people globally work in conditions of vulnerability.[26] These forms of employment are normally characterized by low pay, insufficient social benefits, and lack of legal labor protections, with this mass of insecure workers serving a similar function to Marx’s “Industrial Reserve Army”.[27] It is, therefore, no surprise that an increasing number of Americans report feeling insecure in their jobs.[28] And as many immigration scholars have pointed out, immigrants are the ultimate precarious workers, and, with the mass displacement neoliberal policies have wrought in developing nations, millions of workers have begun migrating to developed nations for economic opportunity. Though immigrant workers are technically entitled to the same labor protections as native workers, their ability to exercise these rights is contingent on permission to be present in the country. This is obvious in the case of undocumented immigrants, but even many authorized migrant workers are vulnerable to having their “legal” status changed to “illegal” if their employer sponsorship is revoked, making migrant groups ripe for exploitation.[29] These various aspects of the neoliberal world order have combined to cause the growth of job-insecurity and wage stagnation in developed nations, along with the mass exploitation of migrant workers and workers in developing nations. With this background in mind, how should we on the left respond to the growing nativist sentiment in American political discourse? First, we need to recognize the two dimensions of immigration policy as restrictions on migrant flows and the labor rights of those migrants. Second, we must acknowledge that these two dimensions cannot be fully separated and have a dialectical relationship. As we have seen, certain sectors of American industry (i.e. agriculture and service industry) are still dependent on securing flows of migrant workers, but they are also interested in restricting immigrant access to labor rights. It has therefore been tempting for many American politicians to focus on increasing rights of immigrants, while simultaneously supporting current restrictions on immigration. But, as I discussed above, access to these rights is contingent on permission to reside within the country. Further, as attempts at restricting immigration and expanding border security over recent decades have proven ineffective, even many of the industries dependent on immigrant labor, have become less resistant to migration controls. As it turns out, massive investments in militarized border security, broad deportation apparatuses, and detention facilities, may not do much to prevent or deter undocumented immigration, but they are effective at subjecting migrant workers to extreme forms of violence making them less likely to join in labor organizing. This shows that if we want to improve immigrant rights, we must also seek to deconstruct the national apparatus of immigration control and detention. This would allow migrant workers to exercise their labor rights and provide labor organizations with a mass of potential new members. This is significant because studies have shown immigrant workers are more likely to join unions than native workers and immigrants often work in the most vulnerable industries who cannot easily outsource labor.[30] In summation, I believe leftist policy should focus on promoting awareness of the neoliberal roots of the deteriorating living standards and working conditions experienced by the working-class over recent decades. This includes teaching the history of rising wages, strong job protections, and better working conditions resulting from labor organizing, and the way these benefits have been eroded by an assault on unions by employers and the government. Further, it must include opening borders and organizing workers in vulnerable industries. But most importantly, it will require solidarity with migrant workers, recognizing them as an asset rather than a problem. Citations [1] History.com Editors. Irish Potato Famine. 17 Oct. 2017, www.history.com/topics/immigration/irish-potato-famine. [2] Marx, "The Duchess of Sutherland and Slavery," New York Daily Tribune, February 9, 1853. [3] MOKYR, JOEL, and CORMAC Ó GRADA. “What Do People Die of during Famines: the Great Irish Famine in Comparative Perspective.” European Review of Economic History, vol. 6, no. 3, 2002, pp. 339–363. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41377928. Accessed 15 Sept. 2020. [4] Benjamin Disraeli, Letter to The Times [Q.d.], www.ricorso.net/rx/library/criticism/guest/Disraeli_B.htm. [5] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [6] Isenberg, Nancy. “Taking out the Trash: Waste People in the New World.” Essay. In White Trash, 17–42. Penguin USA, 2017. [7] Isenberg, Nancy. “Andrew Jackson's Cracker Country: The Squatter as Common Man.” Essay. In White Trash, 105–32. Penguin USA, 2017. [8]“Royal Proclamation, 1763.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/. [9] Thomas Jefferson, et al, July 4, Copy of Declaration of Independence. -07-04, 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib000159/. [10] Charles Hirschman and Elizabeth Mogford, "Immigration and the American Industrial Revolution From 1880 to 1920," Social Science Research 38, no. 4 (2009): 897-920. [11] Sukkoo Kim, "Immigration, Industrial Revolution and Urban Growth in the United States, 1820-1920: Factor Endowments, Technology, and Geography," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 12900 (2007). [12] Lee, Suzy, “The Case for Open Borders.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no4/the-case-for-open-borders. [13] Ibid. [14] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [15] Learning, Lumen. “US History II (OS Collection).” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ushistory2os2xmaster/chapter/the-impact-of-expansion-on-chinese-immigrants-and-hispanic-citizens/. [16] “Foreign Miner's License · HERB: Resources for Teachers.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1714. [17] Rana, Aziz, "Settlers and Immigrants in the Formation of American Law" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1075. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1075 [18] An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to the Chinese, May 6, 1882; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1996; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives. [19] Chin, Gabriel J. “The Great Dissenter Had Limits,” October 23, 2018. https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1996-05-12-1996133020-story.html. [20] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [21] Heer, Jeet. “Operation Wetback Revisited,” April 25, 2016. https://newrepublic.com/article/132988/operation-wetback-revisited. [22] Kitty Calavita, Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S. [23] Denvir, Daniel, and Aziz Rana. “Rethinking Migration with Aziz Rana.” 2019. [24]Wise, Raul Delgado, and Humberto Marquez Covarrubias. “Strategic Dimensions of Neoliberal Globalization: The Exporting of Labor Force and Unequal Exchange.” Advances in Applied Sociology 02, no. 02 (2012): 127–34. https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.22017. [25] Loren Balhorn Oliver Nachtwey, Loren Balhorn, Oliver Nachtwey, Editors, Nicole Aschoff, Faris Giacaman, Daniel Kinderman, Umair Javed, Loren Balhorn Oliver Nachtwey, and Suzy Lee. “Berlin Is Not (Yet) Weimar.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no4/berlin-is-not-yet-weimar. [26] Kalleberg, Arne. “The Social Contract in an Era of Precarious Work,” 2012. https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/media/_media/pdf/pathways/fall_2012/Pathways_Fall_2012%20_Kalleberg.pdf. [27] Ibid [28] Ibid [29] Lee, Suzy, “The Case for Open Borders.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no4/the-case-for-open-borders. [30] “Farm Labor.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed