|

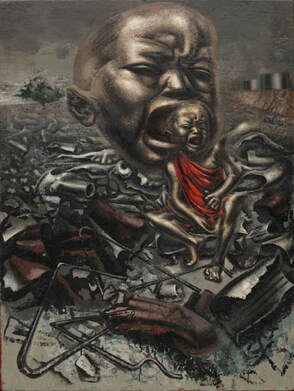

One encouraging development over the past couple decades in American political discourse has been the greater interest in where our food comes from. Unfortunately, this consciousness of the origins of our food has largely come to be associated with veganism and PETA. Which is why I believe it is important to inject a Marxist perspective in order to rescue this issue from the depths of the pretentious, self-righteous vegan politics into which it has often descended. My goal in this essay will be to illustrate the development and consequences of modern industrialized agriculture. Additionally, I will seek to elaborate how global superpowers such as Great Britain and the United States have used control of food supply as a political weapon to exert pressure on disobedient nations and advance the interests of the global hegemon. Finally, I will attempt to demonstrate how these policies have generated many of our past and present mass migrations. A common feature of the early stages of capitalism is the development of "enclosures". Simply put, "enclosing" is a nice word for the forcible privatization of formerly common land. As Marx pointed out: "[a prerequisite for capitalism] is the separation of free labour from the objective conditions of its realization- from the means and material of labour. This means above all that the worker must be separated from the land, which functions as his natural laboratory. This means the dissolution both of free petty landownership and of communal landed property."[1] The appropriation of these lands results in the appearance of large estates and the spread of mono-culture. Mono-culture is the practice of cultivating one crop over a vast area of land, increasing crop yields and making an urban population possible. Unfortunately, this practice excludes the existence of small subsistence farmers and the resulting separation of the laborer from his means of subsistence creates a mass of newly landless people in need of work.[2] Additionally, the increased mechanization of agriculture means that not enough labor is required for all the newly landless workers available, and as the share of the population engaged in agricultural labor steadily declines an ever increasing number of people are left landless and jobless; these are the people who will migrate to cities and compose the urban proletariat.[3] These developments were the substantive content of the British Agricultural Revolution which took place from the 17th century to the 19th century and made the later Industrial Revolution possible. The story is nearly the same wherever capitalist development rears its ugly head and it has been one of the main exports of imperialist powers. As Josue de Castro explains in his book The Geography of Hunger, imperialist nations forced their colonies into mono-cultural production of export crops such as cotton, sugar, and tobacco in order to fuel British industry and feed a growing population.[4] This made up the substance of the British food regime as the dominant global power. The result was mass starvation and chronic malnutrition in colonies whose populations were no longer able to grow various subsistence crops.[5] Thus, Castro claimed: "Hunger has been chiefly created by the inhuman exploitation of colonial riches, by the Latifundia and one-crop culture which lay waste the colony, so that the exploiting country can take too cheaply the raw materials its prosperous industrial economy requires" This resulting in: "tragedies like that of China, where in the nineteenth century some hundred million individuals starved to death, or like that of India, where twenty million people died of hunger in the last thirty years of the [19th] century."[6] Further, the practice of intensive mono-culture tends to deplete soils of key nutrients faster than they can be recreated by nature leading to a rapid deterioration of soil quality, fueling industrial agriculture's thirst for new arable land.[7] Additionally, runoff from chemical fertilizers and pesticides damages local environments, often contaminating water and killing fish.[8] The come up is that these rural areas are left devastated once the agricultural industry has lost interest in them. My own homeland of the southeastern United States is a case-in-point. As de Castro put it: "Few regions of the world have been so ruthlessly sacked and plundered, so wasted by ill-conceived use and by permanent maladjustment of man to his environment."[9] As soon as the first American colonies were established, they were pressured by their corporate sponsors, who were interested in quick profits, into cultivation of export crops on a large scale, establishing cotton, sugar, and tobacco as the main crops of the south.[10] The mono-culture thus practiced in the South led to "the greatest stripping of topsoil ever seen anywhere in the world", and rendered one-third of the South's land completely eroded by 1933. This rapid erosion, alongside an economy based on commercial crops, resulted in a severely malnourished population, with 73 per cent of the population receiving an inadequate diet by 1943.[11] Much of this exploitation was carried out under a system of slavery and aristocratic landholdings, but after the abolition of slavery, it was replaced by the semi-feudal system of share-cropping which broke up many of the large landholdings into smaller plots worked by individual families but was nevertheless rife with exploitation.[12] It also created ample investment opportunities for northern land speculators, leading to a rapid rise in absentee ownership with 66 per cent of southern farms in the hands of absentee owners.[13] As the sharecropping was drawn to an end and industrial capital moved in: "the economic disorganization caused by capitalist land exploitation, mechanized farming and cheap-labor industries resulted in the expulsion of large numbers of tenants and sharecroppers", who composed the hundreds of thousands of people who migrated from the south to the western and northern U.S.[14] This event led to the mass starvation of thousands of southern migrants not to mention the morbidity from chronic malnutrition and disease. This mechanization and industrialization of southern, as well as broader U.S. agriculture, formed the basis for U.S. policies post-WWII and the food regime it would shape as the global hegemon. The increased yields due to mechanization led many U.S. farmers and policy makers to fear overproduction driving down commodity prices, instigating a set of government policies known as supply management. "Supply management" was the combination of the often-contradictory policies of high import tariffs to protect domestic agricultural industry and production controls on certain agricultural commodities, mixed with price supports and export subsidies. These production controls, meant to limit overproduction, were tied to acres under cultivation, not the volume produced; additionally, price subsidies guaranteeing minimum prices were based on volume. This combination encouraged farmers to increase production per acre as much as possible. This compounded with the development and widespread use of chemical fertilizer led to the very overproduction supply management was supposed to prevent.[15] Now the U.S. was faced with the problem of the disposing of surplus agricultural commodities, marking the major distinction between the U.S. and British food regimes: whereas the British structured their regime to ensure the inflow of cheap natural resources, the American regime was designed to ensure markets for domestic agricultural surpluses. This was accomplished by establishing export subsidies and food aide programs designed to dump surplus agricultural production in "needy" nations. The first instance of U.S. food aide occurred after World War II under the Marshall Plan, which provided food and industrial support to feed and reconstruct Europe. This worked as a safety valve for U.S. agricultural surplus for a while, but as Europe's agricultural output rose enough to feed its own population, the U.S. was forced to find new markets for its surplus. The answer came in 1954 with the creation of PL480 which expanded food aide to "friendly", "needy" nations.[16] At this time, in the mid-20th century, many "developing" nations were experiencing an explosion in population growth, and in order to feed their growing populations, they resorted to accepting food aide from the U.S. and other "developed" nations needing to dump excess agricultural commodities, particularly wheat. But, unlike Europe under the Marshall Plan, this aide did not include assistance in developing agricultural production and this injection of massive amounts of foreign commodities decimated domestic agriculture in "developing" nations, contributing to the mass rural-to-urban migration around this time.[17] It also resulted in a massive growth in poverty and growing dependence on the U.S. and other "developed" nations for their food. This dependence also led to the development of diets based on one type of food, particularly grains.[18] This is significant because diets reliant on a single food-type are generally lacking in nutrients needed for a sufficient diet, leading to general malnourishment and disability.[19] The U.S. was then able to use its control over food supply as a political weapon against nations who defied U.S. policy. One such case was President Johnson's withholding of food aide from India because he was displeased with the position the government of Prime Minister Gandhi had taken regarding the Vietnam War.[20] But this ability to control food supply is important in a broader aspect as well. According to Dr. Bill Winders in his book The Politics of Food Supply: "food regimes... help to solidify the position of the world economic hegemon by reinforcing its preferred patterns of production, trade, and development."[21] These policies allowed the U.S. to shape recovery in Europe and development in poorer nations, but as the agricultural production in other rich nations recovered and eventually began producing surpluses, competition for global markets, particularly from Europe and Canada, increased. The use of supply management policies spread to other surplus-producing countries, as well as the use of food aide to dispose of these surpluses. The U.S. food regime operated smoothly as long as prices were low and supply abundant, but it began to crack during the food crisis of the 1970s. When the Soviet Union purchased record amounts of U.S. grain between 1972 and 1974, grain suddenly became less available and prices spiked.[22] And, as I noted above, the injection of food aide into "developing" nations destroyed local agriculture, leaving these nations unable to cope with food shortages. This crisis made the contradictions in the U.S. food regime apparent to many economic actors in agriculture, leading many to push for changes to policy. This was influenced by three factors: As the number of countries practicing supply management continued to increase, competition for export markets became ever more intense throughout the 1970s and 1980s; the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s created potential new markets in former communist bloc nations; and the growing importance of agribusiness operating globally.[23] These three developments created a general push for greater trade liberalization in agriculture. This trade liberalization was established in the mid-90s in the form of free trade deals such as NAFTA and, the ironically named, FAIR Act, as well as the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to enforce these rules of liberalization.[24] This liberalization entailed the retrenchment of major aspects of supply management such as the elimination of production controls and price supports. Taking NAFTA as an example, we can examine the effects this had on global economic conditions. Throughout much of the 20th century, Mexico had maintained trade barriers to protect its domestic production of corn, which was a staple of Mexican diets. NAFTA tore down these trade barriers, opening the Mexican market to U.S. agricultural imports destroying Mexico's domestic agricultural industry which could not compete with cheaper U.S. commodities.[25] In this shift towards trade liberalization we also see an instance where the global hegemon shapes trade policy in its favor. Throughout much of the 20th century, the U.S. pushed for protectionism in agricultural policy, which shielded domestic producers from competition; as other nations followed suit, the number of markets open to U.S. commodities decreased while its competitors increased; thus, trade liberalization was a method to open new markets for "developed" nations, while crushing growing competition in "developing" nations. The collapse of Mexican agriculture coincided with the expansion of the livestock industry, which relied less on family farms and more on contracted operation of large "factory farms".[26] This increased demand for "feed grains" needed to raise livestock helped U.S. farmers and agribusinesses, but left many former Mexican farmers and agricultural laborers landless and jobless. Thus, we see the reappearance of a common theme in imperialist food policy: thousands of poor people, having lost all means of subsistence, migrating in search of a way to make a living. Engels observed a similar phenomenon among the Irish, displaced by famine and enclosures, who migrated to English cities noting, "this competition of the workers among themselves is... the sharpest weapon against the Proletariat in the hands of the Bourgeoisie."[27] This is partially caused by what Marx and Engels termed the "Industrial Reserve Army"- a constant pool of unemployed laborers which capitalists can draw from.[28] According to Marx and Engels, unemployment is required by Capitalism in order to make workers easily replaceable, increasing labor-force competition and keeping wages low. Thus, the displacement of these new migrants give capitalists a convenient way to supplement this reserve army with laborers willing to work for less due to their social vulnerability, driving down wages with increased competition. And in appropriately Machiavellian fashion, the Bourgeoisie then uses this mass of people its policies displaced as a scapegoat for difficulties the working class now faces. The nativist tendencies of the "MAGA" crowd bear a striking resemblance to the reception Irish immigrants received in Britain, and the treatment reserved for "okies" who moved west.[29] In these various instances we are able to see how the chaotic nature of capitalist development in agriculture generates shocks in the political economy of rural areas, leading to mass displacement and rural-to-urban migration. Also, through the analysis of the British and U.S. food regimes, we are able to see how global superpowers leverage their control of food supply to shape international rules of commerce in favor of the global hegemon. These policies have often created the shocks in rural life that produce mass displacement and migration. These mass of displaced persons are then used to supplement the "Industrial Reserve Army", which increases labor competition and drives down wages. Finally, the Bourgeoisie use nativist resentments towards immigrants to divert attention away from the policies on the macro-level which are generating these migrants; instead of recognizing the similarities between their struggle and that of immigrants, the working class is encouraged to blame immigrants for their problems obscuring their underlying causes. I believe this analysis of agricultural policy illuminates many of the issues around immigration in our current political context. With this background established, in my next article, I will attempt to analyze the broader issue of immigration. Citations. 1. Marx, Karl, Eric John Hobsbawm, and Jack Cohen. Pre-capitalist Economic Formations. New York: International Publ., 1984, 67 2. Marx, Karl, “The Duchess of Sutherland and Slavery,” New York Daily Tribune, February 9, 1853. 3. Ibid 4. Castro, Josue d́e. Geography of Hunger. London: Victor Gollancz, 1955. 5. Ibid, 7. 6. Ibid 7. Wilson, Victoria. "How the Growth of Monoculture Crops Is Destroying Our Planet and Still Leaving Us Hungry." One Green Planet. October 29, 2018. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.onegreenplanet.org/animalsandnature/monoculture-crops-environment/#:~:text=Instead of rotating different crops,key nutrient in crop growth. 8."Clear Choices Wants You!" Clear Choices Clean Water. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://indiana.clearchoicescleanwater.org/lawns/fertilizer-impacts#:~:text=Too much fertilizer can actually,dead zones” in coastal areas. 9. Castro, Josue d́e. Geography of Hunger. London: Victor Gollancz, 1955, 128 10. Ibid, 130 11. National Research Council, Food and Nutrition Board, Committee on Diagnosis and Pathology of Nutritional Deficiencies, Inadequate Diets and Nutritional Deficiencies in the United States. Bulletin Number 109. Washington, D.C. November 1943. 12. Castro, Josue d́e. Geography of Hunger. London: Victor Gollancz, 1955, 132 13. Hawk, Emory Q., Economic History of the South. New York, 1934. 14. Castro, Josue d́e. Geography of Hunger. London: Victor Gollancz, 1955, 137 15. Winders, Bill. The Politics of Food Supply: U.S. Agricultural Policy in the World Economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012, 53-60 16. Richards, Lynn, and Lynn Richards. "The Context of Foreign Aid: Modern Imperialism." Review of Radical Political Economics 9, no. 4 (1977): 43-75. doi:10.1177/048661347700900404. 17. Winders, Bill. The Politics of Food Supply: U.S. Agricultural Policy in the World Economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012, 136 18. Ibid 19. Castro, Josue d́e. Geography of Hunger. London: Victor Gollancz, 1955, 31 20. Winders, Bill. The Politics of Food Supply: U.S. Agricultural Policy in the World Economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012, 131. 21. Ibid, 134 22. Ibid, 144-150 23. Ibid, 153-159 24. Ibid, 181 25. Ibid, 182 26. Ibid, 186-187 27. Engels, Friedrich. Condition of the Working Class in England. London: Penguin Books, 1987, 112 28. Marx, Karl. Capital. London: Penguin Classics, 1990, 784-785 29. Gregory, James N. "Dust Bowl Legacies: The Okie Impact on California, 1939-1989." California History 68, no. 3 (1989): 74-85. doi:10.2307/25462394.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed