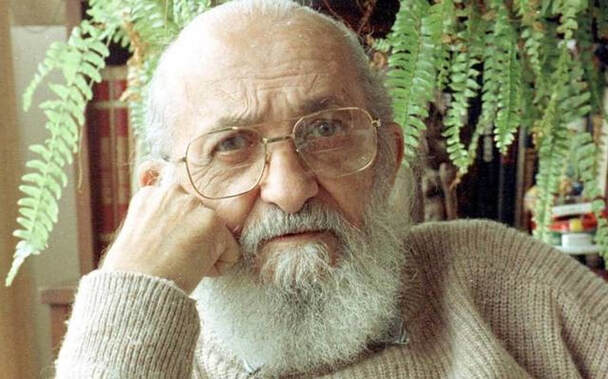

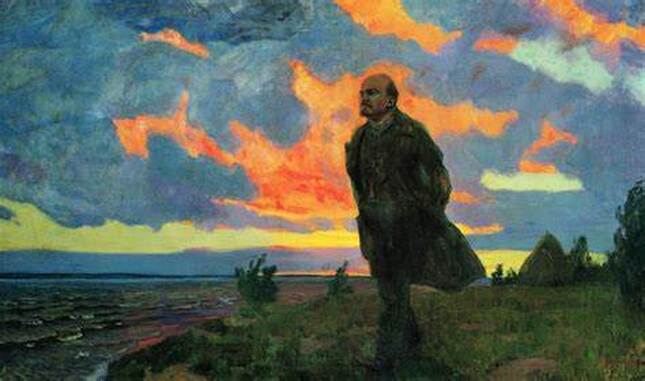

Introduction:The oppressed and their ruling class oppressors have an anti-dialogical relationship with one another, which is to say there is no meaningful dialogue that occurs between them. Instead, the ruling class lays sole claim upon all of the knowledge, norms, and rules that govern our society. In place of a dialogical discourse with the oppressed, the ruling class prescribes authoritative narratives to them. This is how the ruling class is able to exert and maintain their domination of the world, and in doing so, deny any chance for a transformative, radical, and liberating revolution. The ruling class conceals the possibilities of full liberation by “gifting” the oppressed a minimalistic range of rights and liberties that are purely legalistic in constitution and devoid of any economic considerations. This has to be stopped. But how? In what follows, I will attempt to answer this question by advancing a Marxist program for revolutionary vanguard pedagogy. In the first section of this paper, I will elucidate Karl Marx’s distinction between a limited form of freedom, known as “political emancipation,” from a more maximal approach, which he calls “human emancipation.” Additionally, I will introduce Paulo Freire’s pedagogical theorization of the “banking model” of education, which stands in contrast to his formulation of a “problem-posing” method. I will also argue here that political emancipation, as a purely legalistic configuration of rights and liberties, is the only sort of “liberation” that can be conferred to the oppressed by the ruling class. Human emancipation will not be gifted to the oppressed – it must be fought for. In the second section of this paper, I will present the aforementioned pedagogical principles as they relate to revolutionary theory. To do this I will draw upon the works of Vladimir Lenin in conjunction with Freire. In the final section of my paper, I will discuss the differences between these two theorists when it comes to matters concerning the proper timing for vanguard action. Here I will favor Lenin’s skepticism towards a subservience to spontaneity over Freire’s dedication to patience. As such, this paper is centered on what I propose to be the paramount responsibility of revolutionary vanguard leadership, namely, to educate, agitate, and awaken the oppressed Section I: The “Gift” of Political EmancipationThe oppressed cannot rely on their oppressors to bestow upon them the kinds of rights and liberties that are necessary to achieve their full liberation. For this reason, Marx distinguishes two forms of emancipation in his essay “On the Jewish Question.” On the one hand, there is political emancipation, which is purely legalistic and particularly limited in scope and scale. On the other hand, there is human emancipation, which requires the abolition of economic oppression. Human emancipation necessitates this in addition to the attainment of civil rights and liberties for everyone, and as such, can be understood as a maximalist approach towards freedom. As a formal liberal judicial model of rights, political emancipation occurs when the ruling class grants civil rights and liberties to people through the supposed universal application of law, thereby bringing disenfranchised groups into the already existing social-political superstructure.[1] While on face-value this sounds freedom affirming, it in truth only offers a limited conception of equality.[2] This is because political emancipation ignores the consideration of one’s class and is devoid of any concern for one’s material relations. In short, political emancipation is purely legalistic in composition. As a result, political emancipation conceals oppression by giving it a more human face. Indeed, I argue alongside Marx that juridical equality masks other forms of social inequality. While those who are politically emancipated may be free in a sense of the word, they may still remain unfree in material matters. To put it another way, even if all citizens are equal on political grounds, they can still be unequal economically. As a consequence, the ruling class has divided human life into two; the individual in the political realm, and the individual in civil society. The former is regarded as a citizen of a community who is the bearer of abstract rights. The latter individual is regarded as an isolated monad who is merely concerned with their own private affairs.[3] However, this is not to say that political emancipation should not be sought after in our struggle for liberation. In fact, quite the contrary is true. While political emancipation may not be sufficient for the liberation of the oppressed, it is a necessary condition of such. This is because a free and equal society requires the political emancipation of all people. But even if people are politically equal there still might be underlying social inequalities that obstructs a fully exhaustive explication of justice and fairness. For this reason, political emancipation should be considered as only an inclusionary measure, and not a liberatory one. Political emancipation is a great step towards emancipation, but it is only that - a step. Human emancipation requires great leaps forward instead. Most notably, methods of prescription are integral to the oppressed-oppressor relationship.[4] I find that this is a direct consequence of the way in which the ruling class manages any discourse that pertains to the knowledge, norms, and rules of how a society functions. Freire designates this as the “banking model” of education.[5] In the banking model, knowledge is considered to be a gift that is given from the teacher to the student. Consequently, the banking model of education enables the ruling class to narrate and dictate information to the oppressed, who in turn are only able to passively receive and listen to these commands. Ultimately, the banking model culminates into practices in which the ruling class acts as the teachers, while the oppressed are categorized as students who are to be controlled. Additionally, in the banking model of education, the teacher narrates a certain set of content to their students. Here, the task of the teacher is to deposit into the students minds a series of fixed knowledge, norms, and rules, as if their minds were empty containers to be filled. In turn, the student’s job then is to record, memorize, and repeat the information given to them. These students are not permitted to reflect or engage with this content. In this model it is not for the student to ask why two times two equals four, but rather, only to know that it simply is four.[i] In light of this, the banking model can be said to be quite mechanistic in composition. Subsequently, the ruling class has taken the banking model as the way in which the knowledge, norms, and rules of society are applied, presenting themselves as the teachers, while at the same time positioning the oppressed as their students. Anti-dialogical by its very nature, the banking model has been so successful for the ruling class because there is no room for any participation on the side of the oppressed, with the exception of absorbing what is dictated to them. As a result, the banking model does not allow the oppressed to actively participate and transform the world around them. This makes the banking model a particularly dangerous pedagogical approach, as it allows the ruling class to place limitations on the rights and liberties that the oppressed can have. At best, political emancipation is the only form of freedom that can be advanced when the ruling class is permitted to act as teachers who have the exclusive authority to prescribe knowledge, norms, and rules. The ruling class utilizes these pedagogical tactics to ensure their complete control of all our social-political actions and behaviors. In this worldview, it is not for the oppressed to ask or challenge why we must continue to live in a capitalist society, but only to know that it simply is the case that we do. With the backing of the banking model of education the ruling class is able to prohibit all potential revolutionary changes. Simply put, the ruling class uses the banking model to make the possibility of human emancipation untenable. However, it should be noted that a revolution is not a project in which one liberates another. The ruling class cannot and will not lead us in the struggle to overcome oppression. To believe the oppressors would liberate the oppressed is indeed a naive notion. This is why the oppressed must not rely on the knowledge given to them by the ruling class. As Freire attests, “Freedom is acquired by conquest, not by gift” (47). Emancipation cannot be gifted to the oppressed because the ruling class places strict limitations on what kind of emancipation can be achieved in their social-political system. Even though political emancipation has traditionally come from the ruling class by way of integrating citizens into their fold, there is no question that human emancipation cannot come from within this currently existing superstructure. As such, the oppressed cannot use the State apparatus as a means of liberation. In the essay “The Civil War in France” Marx insists that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes” (Marx, 302). To put this another way, the oppressed cannot replace the bourgeois State with a proletariat State, as this would simply be a transference of domination. This would only amount to a substation of power and would not necessarily promote the end of oppression as such. Rather than reconstructing social-political power, an organization such as this merely rearranges it. Hence, the conditions of human emancipation would not be sufficiently met by the creation of a proletariat State. In sum, a full form of freedom cannot be achieved through the mere rearrangement of society, rather, it must be completely reconstructed anew. The conditions needed for the total negation of alienation and exploitation requires the destruction of the oppressor State apparatus. On these grounds, Marx postulates two distinct movements that must occur prior to the actualization of a truly free and equal society. First, the bourgeois State must be smashed. This can be achieved through revolution. The second movement is the withering away of the new State.[6] But what does this mean and how does it happen? While there is no simple or singular answer to this riddle, it must be asserted that the withering away of the oppressor State can only happen when every person is given the opportunity to engage in dialogical discourse and action with one another. With all of this in mind, I will now argue that any attempt to liberate the oppressed must involve their active and reflective participation in how society is shaped. For this reason, members of revolutionary vanguard leadership cannot rely on the same pedagogy used by the ruling class. According to Freire, the oppressed should not be dictated “liberatory” propaganda, nor can they be told what to think or how to act.[7] Instead, Freire asserts the best route to freedom occurs when there is constant and continual dialogue between all members of society. Revolutionary leaders cannot act as banking model teachers in relation to the oppressed, for they must instead enter into a co-intentional form of education with them. This is the only way to combat the contradictions that exist between the student and the teacher - the oppressed and the oppressor - as posited by the ruling class. Thus, communication should be acknowledged as having paramount significance for all matters concerning revolutionary liberation. When dialogical discourse happens, both parties become teachers and students equiprimordially. As Freire states, “Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with students-teachers” (Freire, 80). Freire calls this form of dialogue between teachers and students the “problem-posing model” of education.[8] As the problem-posing model is dialogical, it stands in direct contrast with the banking model. Whereas the banking model teacher prescribes information to students, the problem-posing teacher-student discovers knowledge alongside their fellow student-teachers. Freire says this about the problem-posing teacher-student, “Here, no one teaches another, nor is anyone self-taught. People teach each other” (Freire, 80). Freire’s interpretation of a liberatory pedagogy therefore does not place the oppressed student as a passive listener, but rather, as a critical and active participant. Through dialogue, trust, and love the problem-posing model allows the student-teacher and the teacher-student to work together with one another as co-authors of knowledge, norms, and rules. Overall, education is dialogical if students can contribute to the discourse at hand and it is anti-dialogical when they cannot. Indeed, dialogical action necessitates the possibility of participation. In short, the “Banking education resists dialogue; problem-posing education regards dialogue as indispensable to the act of cognition which unveils reality. Banking education treats students as objects of assistance; problem-posing education makes them critical thinkers” (Freire, 83). This is valuable insight for those who are involved in the revolutionary struggle. From this interpretation we can see that when vanguard leaders fight apart from the oppressed it can only amount to fighting for liberation for themselves and not the people. It follows then, revolutionary leaders cannot adhere to the banking model in order to gain support from the people. Their pedagogy cannot be a top-down approach, as this would mirror the model of the oppressor-oppressed. Freire writes on this matter, “The revolutionary's role is to liberate, and be liberated, with the people - not to win them over” (Freire, 95). Fundamentally, the role of the revolutionary leader is not one of salvation, but instead, of encouragement.[9] Section II: The Responsibilities of the Revolutionary Vanguard LeadershipSince human emancipation cannot and will not be gifted to the oppressed, a revolution towards such must be fought for. But who is to do the organizing for these endeavors, and how should it be done? I propose that this is the responsibility of those who are conscious of issues of class, that is, the revolutionary vanguard leaders. But as I have stated earlier, the way in which a vanguard organizes themselves with the oppressed cannot be done in the same manner that the ruling class does. Instead, they must rally the oppressed in a dialogical fashion. To organize or mobilize the oppressed by means of manipulation, or without them altogether, would be a contradiction of human emancipation, and thus, could not be considered a revolutionary movement. These false vanguards may have different objectives than the ruling class does, but there can be no road to liberation if their pedagogical practices align with the banking model of education. Dialogue and participation from the people is what distinguishes a revolution from a military coup. Leaders of a coupes do not have dialogue with the people, it is done “for” the people. But an attempt to carry out the revolution “for” the people is the same as to carry out the revolution without them, and will never result in the manifestation of human emancipation. Again, it must be stressed: liberation is not a gift, it must be fought for. According to Freire, the strive for one’s freedom is not a concession that can be bestowed upon the oppressed by revolutionary leadership, as it is something that they must become convicted of on their own accord. Yet, Freire notes the average and everyday person is oftentimes not socially or politically conscious. As a result, he advises revolutionary leaders to wait and bide their time patiently, striking only when a mass of people are class conscious. He writes on the matter: It often happens that objectively the masses need a certain change, but subjectively they are not yet conscious of the need, not yet willing or determined to make the change. In such cases, we should wait patiently. We should not make the change until, through our work, most of the masses have become conscious of the need and are willing and determined to carry it out. Otherwise we shall isolate ourselves from the masses (Freire, 94). As we can see from Freire’s account, revolutionary leaders cannot make up the minds for the oppressed, for this is what the oppressor does. Therefore, for Freire, a true revolutionary leader does not impose their values on others. Accordingly, Freire believes revolutionary leaders should not deposit communiques and programs of action to the oppressed. He writes, “There are two principles here: one is the actual needs of the masses rather than what we fancy they need, and the other is the wishes of the masses, who must make up their own minds instead of our making up their minds for them” (Freire, 94). Hence, the oppressed, as masters of their own education, must compose their own program of freedom. Freire continues, “By imposing their word on others, they falsify that word and establish a contradiction between their methods and their objectives” (126). It is clear Freire maintains the position that revolutionary leaders cannot truly know what the oppressed desire by themselves. They can come to an agreement about what sort of freedom they think the oppressed should have, but this is not the same as the oppressed having knowledge on such matters for themselves. In this respect, a revolution built around the pillars and programs of the revolutionary leaders becomes the vanguard’s revolution, and not the revolution of the oppressed. Freire argues that in an instance such as this revolutionary leaders merely replace the role of the bourgeois so they may carry out their own vision of society. It is here that I disagree with Freire. I believe that revolutionary leaders should not wait until the time comes when the oppressed awaken from their socially and politically conscious slumber. Nor can vanguards keep revolutionary discourse to themselves. The indifference towards class consciousness on the part of the oppressed is one of the main reasons why revolutionary movements have moved so slowly and progressed so little. As such, the first task of the vanguard is to cultivate this theory. Then they must educate, agitate, and awaken the oppressed. The problem is then, how should revolutionary leaders educate the oppressed? As problematic as this issue may be, it is clear that we cannot rely on the oppressed to spontaneously formulate the decision to revolt. According to Lenin, revolutionary potential is fundamentally hindered by a subservience to spontaneity. He proclaims we cannot look to spontaneity for a chance at a revolution, as spontaneity is what we have ‘at the present moment.’[10] For Lenin, an adherence to spontaneity only advances the continued subordination of bourgeois ideology. In other words, spontaneity can only lead us to more domination of bourgeois social-political systems. This line of thought is marked by the thinking, “there can be no other way; there is no alternative!” Adherence to the status-quo is easy for the oppressed to follow because it is so entrenched in their daily life and way of thought. This is why Lenin argues that a revolutionary movement must combat spontaneity. I agree with Lenin on this issue. Yet, it cannot be denied that class consciousness exists by way of spontaneity to a certain extent. This is evident when workers go on strike, or when they demand better wages, working conditions etc. However, this is what Lenin calls “trade-unionism,” which is not the same as a class consciousness proper. Per Lenin, “The spontaneous working-class movement is by itself able to create (and inevitably does create) only trade-unionism, and working-class trade-unionist politics is precisely working-class bourgeois politics” (Lenin, 125). Accordingly, trade-unionism should be considered as class consciousness in its embryonic form. Demands and strikes show flashes of consciousness, yet not the full awakening of such. Indeed, spontaneity can only develop this minimal level of class consciousness.[11] Nevertheless, trade-unionism is a good thing, insofar as without it the oppressed lack any hope for progress. But these demands do not lead us to a true challenge against the oppressor-superstructure. Similar to political measures of emancipation, trade-unionist demands do not show knowledge about the antagonisms of class struggle, and as such, they are fundamentally limited when compared to human emancipation. Vanguards are therefore needed because the oppressed are not yet at their height of class consciousness. The aim of the vanguard then, is to help the oppressed develop class consciousness in order to promote a movement that stands in opposition to the oppressor ruling class. In this way, the vanguards task is to prepare the oppressed for revolution. This means revolutionary leaders should spread their understanding of socialism with fervor and zeal to the average and everyday person. The potential for revolution gains momentum by awakening the oppressed to this cause. One of the greatest weaknesses to any revolutionary momentum is the lack of consciousness among most people. Indeed, it appears as if the oppressed are content with political emancipation alone. But this is simply because they have not awakened to the realization that human emancipation is an imperative of justice and fairness. Thus, the task of the vanguard is to educate the oppressed about their political and social standing. Aiming at this goal, Lenin advises revolutionary leaders to use what is known as “exposure literature.” This is the use of leaflets, manifestos, and other writings devoted to exposing the truth of the oppressor-oppressed relationship. The aim of exposure literature is to rouse the oppressed into an awareness of their current material social conditions. For this reason, exposure literature should be utilized to create a stance against the ruling class. Lenin even considered exposure literature to be a declaration of war against the bourgeois status-quo.[12] This is because it is through these writings that the oppressed can become better acquainted with the alienation and exploitation that they suffer at the hands of the ruling class. For once the oppressed learn about the possibility of full liberation through human emancipation the scraps of humanity granted by the ruling class in the form of political emancipation will no longer be satisfactory. These works of agitation should help expand and deepen the demands of the oppressed. Correspondingly, vanguards, as revolutionary theorists, are called upon to publish works that expand upon and intensify the political exposures of the oppressed. To stress, a revolution cannot be spontaneous. For a revolution to happen there needs to be an attempt at such. Human emancipation will not simply arise out of nowhere, and it will definitely not be gifted by the ruling class. It is therefore the responsibility of the revolutionary vanguard to educate, agitate, and awaken the oppressed out of their social-political slumber and help them achieve a sense of class consciousness. Section III: Patience or Agitation?Emancipation, as I have argued, cannot be gifted by the oppressor. As we have seen, there exists a relationship between the oppressed and the oppressor that is fundamentally anti-dialogical. This is because the oppressed are currently unable to be meaningfully involved in the formation of society. In order for the oppressed to gain such a role requires a radical revolution in which they are encouraged to become a part of society as active members. Through the works of Marx and Freire, we learn that this cannot come about through a mere reversal of roles. Moreover, through the works of Marx and Lenin we learn that while political emancipation and trade unionism are good steps in the right direction, they are only that - steps. To gain either of these is no great leap towards liberation, as they are necessary, but not sufficient conditions for such. How we reach the manifestation of human emancipation is what is at stake now. Whereas Lenin argues that the oppressed need to be agitated from without, Freire contends that revolution requires patience. Lenin makes the charge that agitation is the only route out of trade unionism, while Freire claims that such a position isolates the revolutionary leadership from the oppressed. Who then, is correct? If we are led to believe as Freire does, we might lose the potential for a more immediate revolution. This is because Freire wants revolutionary leaders to tread cautiously and patiently towards revolution. For Freire, revolution must be a desire of the oppressed which must come about by their own fruition. This line of thinking has both its merits and its pitfalls. If a revolution is initiated by the people it will take on a much more authentic character than if it was not. In this way, a revolution is truly made by the oppressed. Freire envisions the oppressed entering into dialogue with each other to decide what form of liberation they themselves want, and is not something that is directed “for” them. Assuredly, this has a strong dialogical characteristic about it. Patience of this sorts is beneficial in remaining cognizant of the desires of the oppressed. As Freire argues, any sort of revolution that is not aware of such matters falls under the banking model of education. This is undoubtedly the case when revolutionary leaders treat the knowledge that they hold of class consciousness as a gift. This is why Freire comes to the conclusion that no matter how well intentioned this gift of revolutionary knowledge is, an approach such as this will ultimately result in the banking model, thereby continuing the tradition of oppression. However, as Lenin reckons, spontaneity cannot be relied upon for revolutionary struggle. Spontaneity has created the conditions of present society, which is anything but revolutionary. To be sure, spontaneity has resulted in the mass adherence to the status-quo, and is allied with the forces of pacification. Modern capitalist society has become increasingly structured around the notion of the “pacification of the proletariat.” This is all to say that a large number of the oppressed have become pacified in regard to their social and material conditions. While members of the oppressed might understand themselves as oppressed, they might at the same time be content with their lot in life. Why revolt against the superstructure when they can go home and watch Netflix? Why enter into a political dialogue with anybody when they can play the latest version of Angry birds? Why care about the massive inequalities of wealth in the world when they can consume whatever they want from the comfort of their couches, with free two-day shipping? In other words, liberation is hard, turning on the television is easy. Capitalism has become extremely efficient at quelling thoughts of dissent by way of increased modes of commodification. Everything is commodified in the eyes of capital, which consequently results in the consent of the continuation of the oppressors strangle on knowledge, norms, and rules of society. The oppressed do not see themselves as such, but rather as a consumer. The oppressed have thus become complacent with the status-quo. With such complacency, many oppressed wonder why they should even bother being political at all? This is exactly why exposure literature and measures of agitation on the part of revolutionary leaders is so important. Problem posing education should be used to rouse the oppressed from their complacency with bourgeoisie rule. The oppressed need to be awakened out of their current state of mind, or else they will forever remain subjugated. As I have stated previously, the commodification of all aspects of life has made it extremely difficult for many members of the oppressed class to see themselves as beings who are alienated and exploited. Exposure literature and agitation serves as the rod that revolutionary leaders can use to pry the oppressed out of this state of slumber. It is likely that nothing will change if we are to stick to the rule of spontaneity. This is not to say, however, that the revolutionary leader should act “for” the oppressed. They may rouse them into a state of dissent, but they cannot act alone. Revolution requires action from the people. To act without the people and without dialogue is not a revolution, it is a military coupe. Concluding Remarks:Given the current state of social-political affairs, it seems as if there is little hope for a radical and revolutionary struggle that is guided by the desire for human emancipation, if there is any at all. This is because the ruling class has complete control over the knowledge, norms, and rules that govern our society. This is done through the prescription of the banking model of education, which allows the oppressors to garner total control of the kinds of freedom the oppressed can obtain. A limitation such as this prevents the possibility of full human emancipation. On these grounds, it is the responsibility of the revolutionary vanguard leadership to educate, agitate, and awaken the oppressed out of their slumber, guiding them into an awareness of class struggle. But as I have maintained, a vanguard pedagogy cannot mimic the banking model tactics used by the ruling class. A revolution cannot be done “for” the oppressed, and as such, they must be given the capability to dialogically engage in the discourse regarding the arrangement of societies knowledge, norms, and rules. The question arises then, is Lenin’s revolutionary vanguard theory anti-dialogical? I hold the position that it is not. As Lenin demonstrates, agitation is not the same thing as telling someone what to do. Agitation involves exposing the social and political conditions of the oppressed. It remains the decision of the oppressed what to do with that information. Agitation is important because without it many members of the oppressed would fall into the complacency set forth by spontaneity. Agitation is not anti-dialogical, as it encourages participation in dialogue. Indeed, without agitation there is likely to be no dialogue. Agitation is done so that the oppressed may enter into dialogue with the oppressed. Agitation is not done as a narrative monologue, as is the case in the banking model. Agitation is done as a problem-posing dialogue. Agitation serves to initiate the conversation between those with class consciousness and those without. In short: agitation is a call to dialogue. Notes [1] Marx defines “political emancipation” as that which occurs when “The state abolishes, in its own way, distinctions of birth, social rank, education, occupation, when it declares that birth, social rank, education, occupation, are non-political distinctions, when it proclaims, without regard to these distinction, that every member of the nation is an equal participant in national sovereignty, when it treats all elements of the real life of the nation from the standpoint of the state” (Marx, 8). [2] Marx writes on the issue, “The limits of political emancipation are evident at once from the fact that the state can free itself from a restriction without man being really free from this restriction, that the state can be a free state without man being a free man” (Marx, 7). [3] Per Marx, “Political emancipation is the reduction of man, on the one hand, to a member of civil society, to an egoistic, independent individual, and, on the other hand, to a citizen, a juridical person” (Marx, 21). [4] According to Freire, “Every prescription represents the imposition of one individual's choice upon another, transforming the consciousness of the person prescribed to into one that conforms with the prescribers consciousness. Thus, the behavior of the oppressed is a prescribed behavior, following as it does the guidelines of the oppressor” (Freire, 47). [5] Freire provides us with this definition, “This is the “banking” concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits” (Freire, 72). [6] For more on this see Marx’s essay “The Civil War in France.” [7] As Freire implores, “Those truly committed to the cause of liberation can accept neither the mechanistic concept of consciousness as an empty vessel to be filled, nor the use of banking methods of domination (propaganda, slogans—deposits) in the name of liberation” (Freire, 77). [8] Freire provides us with this definition, “In problem-posing education, people develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with which and in which they find themselves; they come to see the world not as a static reality, but as a reality in process, in transformation” (Freire, 83). [9] Cautiously, Freire advises revolutionary leaders to “not go to the people in order to bring them a message of "salvation," but in order to come to know through dialogue with them both their objective situation and their awareness of that situation” (Freire, 95) [10] See (Lenin, 67) for more on this. [11] For Lenin, “This shows that the “spontaneous element,” in essence, represents nothing more nor less than. consciousness in an embryonic form… The strikes of the nineties revealed far greater flashes of consciousness… The revolts were simply the resistance of the oppressed, whereas the systematic strikes represented the class struggle in embryo, but only in embryo” (Lenin, 74). [12] See (Lenin, 120) for more. Work Cited Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. Marx, Karl. Karl Marx Selected Writings. Edited by Lawrence Hugh Simon, Hackett, 1994. Vladimir, Lenin. Essential Works of Lenin: “What Is to Be Done?” and Other Writings. Edited by Henry M. Christman, Dover Publications Incorporated, 1987. AuthorRobert Scheuer is a Social Ecologist from Southeast Michigan. He received a M.A. in Philosophy from Eastern Michigan University, and a B.A. in Philosophy from Michigan State University. His research is concentrated on Social Ecology, Marxism, anarchism, and Phenomenology. He also has substantial research interests in Aesthetics, Existentialism, and Philosophy of Education. Archives May 2021

1 Comment

Kenneth 1960

5/18/2021 10:18:42 am

Marvelous essay Robert!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed