|

@PMA_Union via Twitter “The art museum is Philadelphia,” curator Amanda Bock said. “There’s no art without art workers, so if you enjoy coming to the museum, seeing art, you need to support the people who make that possible.” Bock and 180 Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) curators, educators, archivists, and other art workers aren’t feeling that support from one of the nation’s largest, oldest, and most venerable institutions. So, workers struck the PMA on Sept. 26, demanding a voice at work, livable wages, affordable healthcare, and job security. “A lot of people say you can’t eat prestige,” said Adam Rizzo, president of AFSCME Local 397, representing PMA workers. “I think that’s true.” The PMA is known by its iconic front steps, made famous in the Rocky movie. The workers struck after two years of stalled negotiations and union busting by museum management, who refused to meet the worker’s contract demands even halfway. Management offered an 11% salary increase through 2024, unacceptable to workers who have already labored without a raise for three years, including during the pandemic and the current inflation spiral. PMA management has opted to keep the museum open and bring in scabs to install the upcoming exhibit featuring the works of French artist Henri Matisse. Striking art workers have appealed to art lovers not to cross the picket line to view the Matisse exhibit. “Scabby the rat” has a permanent presence in front of the museum. “It is not hyperbolic to say our union’s fight for a fair contract…is a fight to save one of the world’s great art museums,” the union tweeted in early August. The workers want a livable wage commensurate with their education and training. They also want to make the institution more responsive to the needs of the diverse Philadelphia community. The battle at PMA reflects a broader crisis of major cultural institutions nationwide and their prevailing model. Billionaires, corporate lawyers, and politically-connected individuals run the institutions. Their class and social bias prevent them from appreciating their employees’ struggles and the wider multi-racial working-class communities the institution serves. Museum management is also out of touch with the swirling debates about how to make modern institutions more responsive to the emerging diverse and democratic multicultural world, including the repatriation of looted artifacts, something art workers have been grappling with for years. Museum management has proven ill-equipped to respond effectively to growing challenges to dominant white supremacist, patriarchal and elitist culture traditionally shaping their operations. Under the direction of the corporate and wealthy patrons, museums are run like corporations, accumulating huge endowments, spending billions on massive expansions, and bloated administrative salaries while forcing the staff to work for poverty wages. The 2020 median annual wage for archivists, curators, and museum workers was $52,140, according to the Labor Statistics Bureau. PMA is no different. The museum has a $500 million endowment and a $60 million annual budget. Executives make $500,000 or more per year, and the PMA chose to build a $233 million expansion rather than invest in those who make the museum operate. Management refuses to raise the minimum hourly pay from $15 to $16.75. Management has resisted transparency in what it pays each employee. It took the Art and Museum Transparency spreadsheet that allowed workers in the industry to share their salaries discreetly. One PMA worker found out she makes less than the fellows and interns she supervises. As a result, PMA and other museums are seeing a surge of unionization of their workers, mainly with AFSCME and UAW. In 2020, 89% of PMA workers voted to join the AFSCME. Security guards and maintenance workers were already unionized.

The workers say PMA management takes advantage of art workers’ commitment and passion for their jobs and cultural institutions. The low wages are forcing a high turnover, which doesn’t seem to concern management. Often management promotes a worker, and their former position goes unfilled. Previously permanent positions are now temporary or “term” positions. The result has been severe understaffing. “We’re bleeding talented colleagues because of the museum’s low pay, poor benefits, and lack of professional development and advancement opportunities,” wrote PMA employee Emily Rice. “We no longer have enough staff to function properly. We have no archivist, no rights and duplication specialist, no database manager for collections; We only have one paper conservator, one taxidermist and one press officer. Each remaining employee covers the work of two or three people.” Artists and cultural workers across the country, including museum workers in new unions at the Museum of Modern Art, Chicago Art Institute, and Brooklyn Art Museum, are sending solidarity and supporting the PMA strike fund. After expressions of solidarity inundated the PMA’s social media, the museum announced it was shutting down the comments section. AFL-CIO president Liz Shuler joined the picket line on Oct. 8. Both AFSCME and the AFL-CIO held mass rallies with PMA workers during their conventions this past summer. “Solidarity with @PMA_Union on strike. Every @philamuseum employee deserves respect, fair pay, and affordable health care. What goes great with some of the very best art in the world? A Union! 100%,” tweeted John Fetterman, Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate. Correction: This article originally attributed an article written by PMA staff member Emily Rice to the wrong person and included an incorrect hyperlink. People’s World apologizes for the error. AuthorJohn Bachtell is president of Long View Publishing Co., the publisher of People's World. He served as national chair of the Communist Party USA from 2014 to 2019. He is active in electoral, labor, environmental, and social justice struggles. He grew up in Ohio, Pittsburgh, and Albuquerque and attended Antioch College. He currently lives in Chicago where he is an avid swimmer, cyclist, runner, and dabbler in guitar and occasional singer in a community chorus. This article was republished from People's World. Archives October 2022

0 Comments

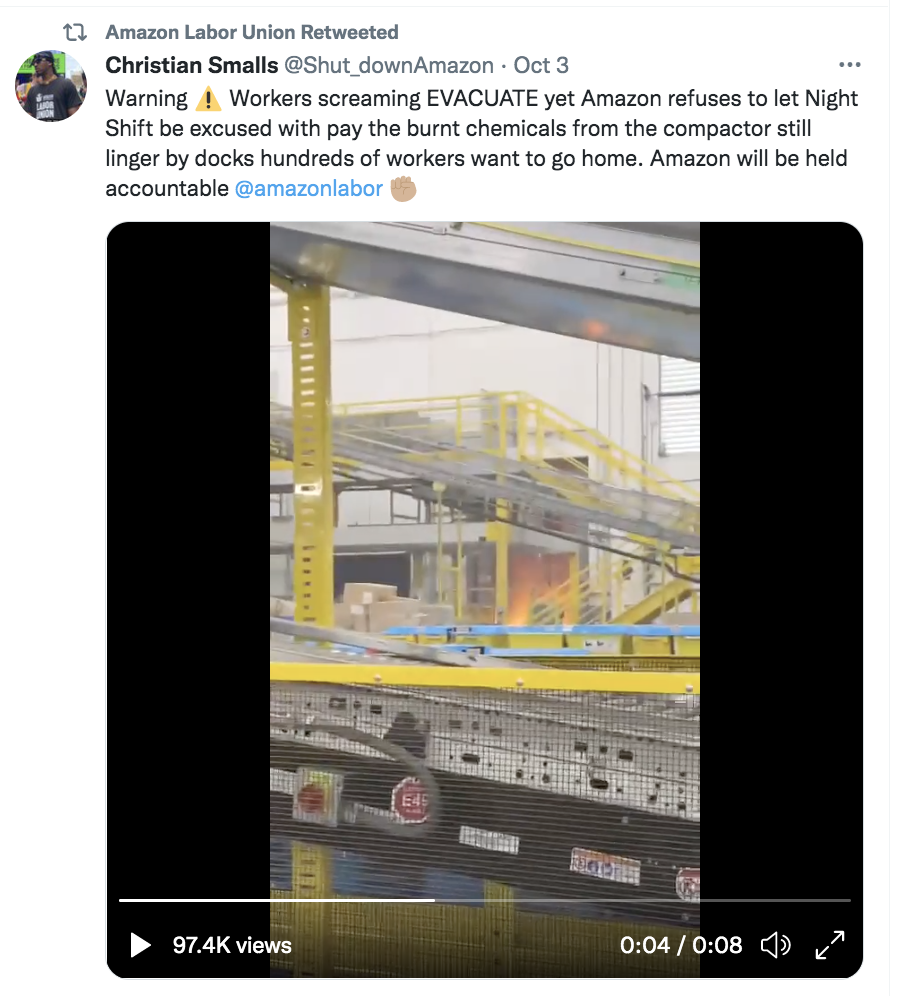

10/17/2022 Amazon suspends 80 workers for refusing to work following dangerous fire By: Jacob BucknerRead NowThe Amazon Labor Union says that more than 600 workers initiated a work stoppage and occupied the break room, refusing to work after a cardboard compactor caught fire in the warehouse. | @IssaSmallsWorld via Twitter STATEN ISLAND, N.Y.—In the late afternoon of Oct. 3, a fire occurred at the sorting center at Amazon’s JFK8 warehouse here. The blaze started when a cardboard-box compactor at a loading dock ignited just before the scheduled shift changeover. With fumes and the smell of chemicals still hanging in the air after the fire was doused, Amazon ordered workers arriving for their evening shift to get to work—even after the employees expressed concerns for their health. As a result, 650 workers entered the break room and another group went to the Human Resources department demanding they not be subject to unsafe working conditions. Amazon responded by suspending 80 workers in what labor leaders are calling a clear act of anti-union retaliation. The incident is the latest episode in a long history of the company refusing to uphold safety protocols, risking workers’ lives in order to secure maximum profit. Around 4:00 pm, workers first reported the fire at the loading dock compactor. Employees could be seen on video screaming “Evacuate!” while running away from the blaze. At the same time, Amazon ordered workers to exit through the much slower turnstiles instead of the emergency fire exits, raising the danger that workers could be trapped inside the building. The company also refused the request by night shift workers starting their day to go home instead. The evacuated employees were made to stand outside in cold, 50-degree rain in the parking lot for an hour while waiting for FDNY to arrive and battle the fire. Once the initial fire was extinguished, the day shift workers were allowed to leave an hour early with pay. But the company announced that all evening shift employees must report to work, saying the warehouse was deemed safe.

Workers on the ground, however, say that as many as 650 employees sat in the break room demanding they be sent home, stating that the working environment was dangerous for their health. After a few hours, Amazon demanded the workers go back to work and leave the breakroom, but many stayed behind to protest the unfair treatment. At around 9:00 pm, about 100 of those employees did a “march on the boss,” going to the HR office and demanding night shift be sent home with pay. The fire itself may have been an avoidable event. Amazon Labor Union lawyer Seth Goldstein says the compactor had been causing problems and smoking for weeks. What was Amazon’s solution to this clear hazard to workers’ safety? The multibillion-dollar company had been pouring water on the compactor to stop the smoke. They could have prevented this risk to employees’ health by evaluating the compactor, but this delay was apparently deemed impossible because it would cut into valuable profit. How did the company respond?After the work stoppage ended, 80 workers were suspended. The company placed them “under investigation” after they spoke up about safety hazards. These suspensions were done haphazardly, and seem to be targeted and malicious. One worker reported that while all the women in her department who participated were suspended, none of the men were. The company has also tried to obfuscate the safety concerns and downplay the necessity for union activity. When the employees walked into the break room as an act of protest, management misstated the number of employees were involved in the walk out. Chris Smalls, ALU president, said 650 refused to work in what they felt to be potentially dangerous conditions; the company claimed only 100 employees were involved—intentionally trying to downplay the scale of the action. The ALU said, “The ‘small group’ that refused to return to work made up 30% of the building by management’s own admission.” Additionally, Amazon spokesperson Paul Flaningan publicly stated, “All employees were safely evacuated,” but this did not acknowledge the many workers who reported tearing up from exposure to smoke or the worker that had to be sent to the hospital from smoke inhalation. Amazon’s report on the incident also did not account for the residual water, dust, debris, and potentially toxic chemicals being exhumed in the aftermath of the fire. All of this is in an attempt to not only camouflage to the public how often Amazon puts workers lives at risk, but also to erode support for the union. Amazon workers lives have been at risk before This is not the first time Amazon workers have had their lives put at risk for company profits. In 2021, as Tropical Depression Ida killed 14 people in the area surrounding JFK8, employees were still expected to go into work. Additionally, in the same year, a deadly tornado in Edwardsville, Ill., killed six Amazon workers because the company refused to close their warehouse in the middle of the storm. In fact, in recent days, there have been three fires at different Amazon warehouses throughout the country. Workers should not have to choose whether they will lose their job and maintain safety or keep their job and risk exposure to toxic chemicals, natural disasters, and death. But this is the sacrifice the company expects employees to make because without workers’ constantly exploited labor, Amazon’s entire basis for profit would be affected. JFK8 is one of the most productive warehouses in the county, and the company would rather sacrifice the safety of employees than halt production and distribution at this key facility. Recognize the ALU!

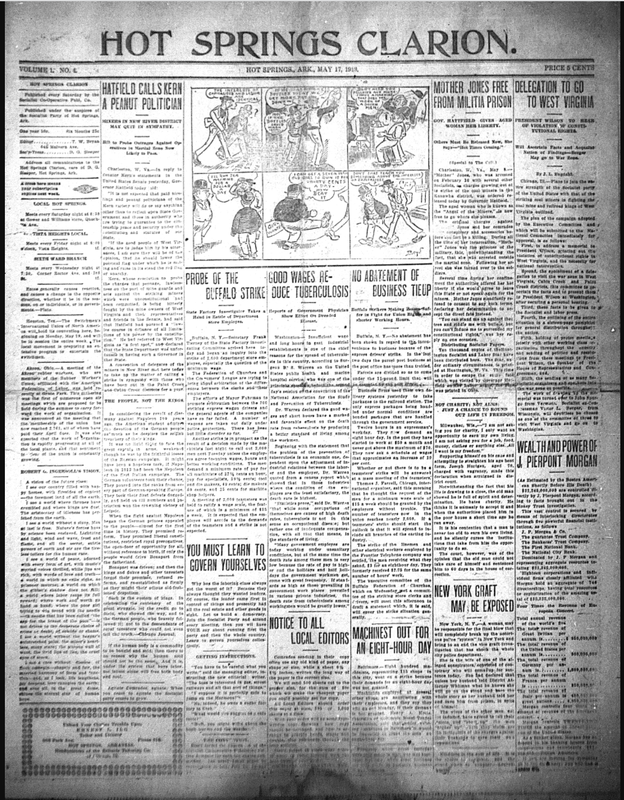

Additionally, the company announced it would invest $1 billion dollars into higher wages, however, it has so far moved ahead on a mere $0.25 raise, and that after a year -long review process. The ALU points out that, with inflation rising to 9.1%, it is actually a cut in real wages by $1.85. This union says the situation proves once more the necessity of collective bargaining representation. But the company is still trying to use its meager increase in wages as a tactic to devalue the union’s importance and convince workers that organizing is against their fundamental interests. The company continues to refuse negotiations with the Amazon Labor Union. It is still campaigning to invalidate the election at JFK8, calling on the NLRB not to accept the outcome and accusing the government body of unfairly favoring the union because it denied all 25 objections Amazon made to the vote count. For highly exploitative capitalist companies such as Amazon and Starbucks (which has seen 240 of its stores go union) a collective bargaining agreement threatens their total control over workers and their labor. But the ALU isn’t quitting, and the fire at JFK8 has pushed it to fight even harder to ensure workers’ lives are not put at risk and to make it clear that workers have the power when they are united. As with all op-eds published by People’s World, this article reflects the opinions of its author. AuthorJacob Buckner writes from New York. Jacob Buckner escribe desde Nueva York. This article was republished from People's World. Archives October 2022 A worker at the International Paper mill in Prattville, Alabama, was performing routine maintenance on a paper-making machine in mid-June when he discovered liquid in a place it didn’t belong. He stopped work and reported the hazard, triggering an inspection that revealed a punctured condensate line leaking water that was hotter than 140 degrees and would have scalded the worker or fellow members of the United Steelworkers (USW). Instead of causing a serious health and safety risk, the leak was repaired without incident. “We fixed the issue,” recalled Chad Baker, a USW Local 1458 trustee and safety representative. “It took about 30 minutes, and we continued on with our work, and nobody got hurt.” Unions empower workers to help build safer workplaces and ensure they have the freedom to act without fear of reprisal. No one knows the dangers of a job better than the people facing them every day. That’s why the USW’s contract with International Paper gives workers “stop-work authority”—the power to halt a job when they identify a threat and resume work after their concerns have been adequately addressed. “We find smaller issues like that a lot,” Baker said, referring to the leaky condensate line. “Most of the time, they’re handled in a very efficient manner.” Workers forming unions at Amazon and Starbucks, among other companies, want better wages and benefits. But they’re also fighting for the workplace protections union workers enjoy every day. Amazon’s production quotas resulted in a shocking injury rate of 6.8 per 100 warehouse workers in 2021. That was more than double the overall warehouse industry rate and 20 percent higher than Amazon’s 2020 record, according to an analysis of data the company provided to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Driving for Amazon is also perilous. About 20 percent of drivers suffered injuries last year, up 40 percent from 2020, with many of these workers reporting that they felt pressured to take unnecessary risks, like forgoing seat belts and skipping breaks, to meet the company’s relentless delivery schedules. Unions fight against all of this. They enable workers to hold employers accountable. That’s why Amazon and other companies pull every trick in the book to try to keep workers from organizing. “We talk. We come up with solutions,” Baker said of Local 1458 members. “It’s kind of hard for the company to disagree with us when we’re all saying the same thing. That commands respect. One of the biggest pluses we have is not being able to be run over.” Baker is one of seven USW members serving as full-time, company-paid safety representatives at the mill, positions that are shared by Local 1458, which represents maintenance workers, and by Locals 462 and 1978, which represent workers in other jobs. They make the rounds of the complex every day to look for hazards, communicate with members and address safety issues, noted Local 1458 President Chad Manning. “You can actually solve the problem when you have the right people involved, who are the people doing the work,” he explained. After workers expressed concern about shoulder injuries, for example, the union persuaded International Paper to replace the manually operated elevator doors with automatic doors. Some workers wear heavy insulated suits to protect them from fire, chemical exposure and other dangers. After union members cited mobility constraints in the bulky suits assigned to them, they worked with the manufacturer, who sent representatives to the mill, to design a better version that International Paper ultimately purchased. With the union’s help, workers also successfully fought for handrails, better lighting and other measures that contribute to a safer workplace and environment. When incidents occur, unions play a major role in investigations that uncover the root causes and work toward eliminating and controlling the hazards. Researchers at the University of Minnesota studied data on more than 70,000 workplaces and found that the unionized locations were 30 percent more likely to have experienced state or federal inspections for safety violations. That’s because unions help members understand their rights and protect them from retaliation. “At the end of the day, it’s the voice. You have one,” Manning observed. “In non-union shops, you don’t have that. You have a good opportunity of being fired if you voice your opinion.” Unions continually seek new approaches for enhancing health, safety and environment. Later this year, the USW will hold a series of trainings to bring additional protections to the growing number of members working in hospitals, nursing homes and other health care settings. These sessions will focus on developing solidarity around safety as well as on hazard identification, incident investigation and holding employers accountable. Then these workers will go back to their workplaces, advocate for their coworkers and encourage them to do the same. “Everybody has something to bring to the table,” explained Melissa Borgia, a member of USW Local 7600, which represents thousands of workers at Kaiser Permanente facilities in southern California. Borgia, who works in membership administration at Kaiser, volunteered to help implement the program because of the pandemic, assaults on health care workers and other dangers her coworkers face. “There is no better time than now,” she said. “This is where the spotlight is.” In Prattville, soaring summer temperatures in the last week of June exacerbated the threat of heat stress at the paper mill. Baker collaborated with the company to purchase tens of thousands of dollars in cooling fans, and now, union safety representatives will continue to monitor conditions and keep workers safe. “We try to work together,” Baker said of management. “Everyone wins when we’re safer.” AuthorTom Conway is the international president of the United Steelworkers Union (USW). This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute. Archives July 2022 Photo credit: Yinan Chen on WikiMedia Commons (CC0 Public Domain). Late 19th and early 20th century Hot Springs, Arkansas was a breeding ground for corruption. A police department controlled by the wealthy collected debts for the powerful families that ran the city, Al Capone visited the Arlington Hotel regularly, and firefights in the street were a common occurrence. Poverty was rampant and brutal. Amid this chaotic backdrop, the Socialist Party of Hot Springs began publishing a socialist newspaper called Clarion. What follows are excerpts and clippings from the only issue available – published May 17, 1913 – in the Arkansas state archives. Hot Springs ClarionPublished every Saturday by the Socialist Co-Operative Publishing Company. Editor… T.W. Bryan Secretary & Treasurer… D.G. Sleeper Local Hot SpringsMeets every Saturday night at 8:?? at Gower and Williams store [unintelligible] YOU MUST LEARN TO GOVERN YOURSELVESWhy has the laboring class always got the worst of it? Because they always thought they wanted leaders. Of course, the leader came first in control of things and presently had all the real estate and goods in sight. Let us build a democracy. Join the Socialist Party and attend every meeting, then you will have YOUR say about running first the party and then the whole country. Learn to govern yourselves collectively. Socialist Party Members in the ProfessionsAn effort is being made by the Information Department to collect the names of the members of the Socialist Party who belong to the professions. There is a two fold object in this effort – first, to show the proportion of educated and especially trained men in the Socialist Party, and, second, (and what is very much more important) to enlist the technically trained comrades in the constructive work which the party must do. More and more the comrades everywhere are realising their need of technical information that can be relied upon to help them in their tasks as members of city councils, school boards and state legislatures. Already a number of consulting engineers, scientists, special students and others are assisting the party thru this department. It is hoped that this list may be greatly lengthened and strengthened. Comrades who themselves have some technical training in any particular line, or who know of comrades who have such attainments, should send the information to this department and correspondence will be opened with them. Notes from our local papersUnder a co-operative government there would be nothing of value with which to bribe a public officer. As mining stock and railway stock would be like stock in a post office or public road. Everyone would have all they could use, but wouldn’t walk a city block for some other fellows share. Money can never be a true measure of value, for it is a product of labor and creature of law, and is no truer or nearer correct than watched or baled hay would be. There are those who are tired of measuring their own value of their happiness and the welfare of their posterity, by so changeable a standard as money. –McAlester Comrade May Walden was with us three days this week. She is woman’s correspondent for the state of Illinois, and is doing special work among the women. The cry now is “A 50 percent woman membership in the Socialist Party.” A very interesting meeting was held at the Unitarian church in which Comrade Walden impressed upon the ladies the importance of Socialism to the women. –Moline We notice that in the Sunday issue of the Arkansas Gazette, an entire page of the magazine section was devoted to the exposure of the Krupp Gun Works in Germany, by the socialist leader, Dr. Leibnecht. He charges that the Krupps were responsible for the semi-annual German-France war scare that consumes so large an amount of space in the Capitalist dailies has been fully substantiated, the Krupps admitting that they bought French newspapers for the purpose of fanning the hatred supposed to exist between the two nations for the purpose of selling armor/plate and guns to the government. Some day when the facts are brought to light we will find the Steel Trust is behind the anti-Japanese agitation in this country, and in the light of recent developments, that anti-Jap [sic] act of the California legislature is significant. This much is certain – even though murder machine manufacturers are able to buy newspapers to fan the flame of international hatred, if the workers of the world will refuse to furnish the corpses there will be no more wars. What We Stand For For a world without a master, a world without a slave. Where none shall kneel and ask permit to work, or favor crave. Where thrones and kings and priests and snobs, and creed and greed are past. For human brotherhood is law, And love’s enthroned at last. A world where right and reason rule, and law supreme of love, As Jesus said when here on earth, The Kingdom from above. Rev. Geo. D. Coleman Socialism the Way Out In the place of the present capitalist system Socialism proposes the new social order – the collective ownership and the democratic operation of the natural resources and social utilities upon which the coming of life and labor of the people depend for the common good of all. This, the Socialist movement declares to be the supreme issue – the only possible solution – the only [?] relief – the only program worth while. Compared to this, everything else is unimportant. Without this, everything else is useless. Henceforth Socialism is the supreme issue – the only way out. However while holding firmly and steadily to the final goal the Socialist party nevertheless offers a constructive program for immediate action, formulates measures that will aid in bringing about the new socialist order, and leads the way in the struggle for the higher civilization. –Socialist Campaign [unintelligible] AuthorArkansas Worker This article was produced by Arkansas Worker. Archives March 2022 3/3/2022 There’s No Sugarcoating Hershey’s Abuse of Workers and Union-Busting Tactics. By: Sonali KolhatkarRead NowHershey factory workers in Virginia are sick of company abuses and are voting to join a union. But their union-busting employer has other plans. There is a bittersweet battle taking place in Stuarts Draft, Virginia. Workers at the Hershey Company’s second-largest factory, located in the small town of about 12,000, are seeking to unionize. In response, the nation’s largest candy manufacturer is throwing the full force of the standard corporate union-busting playbook at them. The Virginia Hershey manufacturing plant employs about 1,300 people, none of whom are sharing in the bounty of the company’s record profits reaped during a pandemic where Americans ate their weight in candy through numerous lockdowns. Nearly two years ago, Virginia’s former governor, Ralph Northam, a Democrat, approved the granting of about $1.6 million in tax dollars to expand Hershey’s Stuarts Draft factory. Fawning over the project, Northam said, “As we work to accelerate Virginia’s economic recovery, existing corporate partners like The Hershey Company are leading the way with new hiring and investment.” He continued, “We thank Hershey for its continued confidence in Virginia and its people.” Brian Ball, Virginia’s secretary of commerce at the time, was even more ingratiating than Northam, saying, “we stand ready to do what we can to ensure the company’s Stuarts Draft operation continues to thrive.” As a result of its investment, the company became eligible for tax breaks and credits in the state. More than a year after Northam’s decision to invest public funds into the Virginia factory, the company posted significant profits, boasting in a press release about “stronger than anticipated consumer demand, an improved tax outlook and optimized brand investment, which, collectively, are expected to more than offset higher supply chain costs and inflation.” Months later, Hershey raised the prices of its products, in line with the increasingly common practice by corporations to squeeze greater profits from consumers and then blame “inflation” for the higher price tags. If taking advantage of public funding while hiking prices for consumers wasn’t enough, Hershey now stands accused of mistreating workers, some of whom are speaking out about grueling work hours, company surveillance, and harsh retaliation. They even refer to the factory as the “Hershey Prison.” One woman named Janice Taylor told the labor media outlet More Perfect Union that she was required to work for 72 days consecutively. She said, “I was exhausted both physically and mentally.” Taylor and others also detailed how Hershey has created a two-tier system at the factory where newer workers are paid less and have significantly fewer benefits. Employees of the Hershey factory in Stuarts Draft are also making themselves heard by leaving reviews on Indeed.com complaining that people have to work “so many hours [that] everybody walks around like zombies.” One worker writes that they had to miss their daughter’s graduation because the company would not give them two hours off to attend. Another explains, “Most weeks you work 7 days and it’s hard to get a day off. Really hard if you have a family.” And another says, “You don’t get to have a life… [it’s] work until you drop.” It’s no wonder the Hershey workers in Stuarts Draft voted on a plan in January to hold union elections to join the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union (BCTGM). Ballots were mailed out in late February, and results are expected to be announced in late March. According to the Guardian, Hershey is “publicly opposing the effort, encouraging workers to vote against it and hiring the union-busting Labor Relations Institute to hold captive audience meetings with workers.” The company is so proud of its Stuarts Draft factory being a non-union workplace that it touts this fact in its job listings, such as this one for an accountant position which starts off saying, “The Hershey Company Stuarts Draft plant is a Non-Union plant producing products… in a high-speed complex environment.” The company’s opposition to the union drive is puzzling considering that since 1938, workers at Hershey’s original Pennsylvania factory have been unionized under the same union, BCTGM Local 464. But Hershey opposes its Virginia workers from having similar labor rights. The company even created a website to fool workers into believing that their interests are the same as the company’s shareholders, board executives, and upper management. On WeAreHersheySD.com, Stuarts Draft-based employees can read about why the BCTGM—the same union that their colleagues in Pennsylvania are members of—is not good enough for them. “An old adage reminds us to ‘choose our friends wisely,’” says the company on its anti-union website, suggesting that a corporate employer whose goal is to suck as much labor from its workers in exchange for as little compensation as possible is a better friend to workers than a union could be. A more honest rejoinder would be, “Corporations are required to maximize shareholder profits—even at the expense of workers’ well-being.” Hershey’s effort to create a fake culture of corporate allegiance among workers using a slick website is an increasingly common tactic, reminiscent of Amazon’s Doitwithoutdues.com and Starbucks’ We Are One Starbucks. Absent from Hershey’s anti-union website is any mention of how Kellogg’s cereal workers, using their collective bargaining power through the BCTGM, recently ended a monthslong strike and won a new five-year contract. Hershey workers in Virginia are fighting to end the same two-tiered system of pay and benefits at their factory that Kellogg union workers successfully ended by going on strike. There are indicators that Hershey is nervous about the union activity. The recent timing of what the company called a “planned retirement” of a plant manager who had reportedly faced numerous complaints from workers led a BCTGM organizer named John Price to infer that “corporate management solicited grievances from workers and forced him to retire.” Price told The News Leader, “The company is in the midst of superficially fixing as many complaints as possible to avoid having to deal with their workers organized as a union.” He alleged that the company may even be “violating the National Labor Relations Act by bribing or buying the potential voter off.” The union efforts at Hershey’s Stuarts Draft, Virginia, factory are part of a growing, nationwide trend among workers that includes big-name companies like Starbucks and Amazon. A successful unionization vote at one Starbucks location in Buffalo, New York, has now sparked similar efforts among more than 70 Starbucks stores in 20 states. Workers in Bessemer, Alabama, are redoing a union vote that Amazon had illegally interfered in as per the National Labor Relations Board. Amazon, which may be the most ruthless anti-union employer in the nation, is continuing to interfere the second time around, indicating its desperation to prevent unions from taking hold. Even museums are seeing union activity around the country, with workers at major art institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Guggenheim, forming and joining unions. And, in early February, the Biden administration issued a set of recommendations “to promote worker organizing and collective bargaining for federal employees, and for workers employed by public and private-sector employers”—a far cry from the blatantly anti-union posture of Biden’s predecessor. Hershey enjoys a reputation for being a just company. It runs a private school for low-income children in Pennsylvania. Its CEO Michele Buck has boasted about its commitment to sustainability, social responsibility and human rights. In an online talk last year, Buck even said that during the pandemic her company was focused on “the well-being of our employees,” including “their emotional well-being and their economic well-being.” And yet, counter to this sugarcoated reputation, the company has drawn a sharp line when it comes to the collective power of some of its workers to demand dignity, safety, and fairness. AuthorSonali Kolhatkar is the founder, host and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute. This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute. Archives March 2022 In any capitalist society, a disconnect between an individual’s selfhood and her labor will arise. Ask any college student and you’ll hear about the never-ending questions that go something like… What career do you want with your degree? What field are you looking into? Where do you want to work once you graduate? Inevitably accompanying that question comes intense anxiety for the student themselves. Yet, this isn’t an issue only experienced by college students— questions concerning one’s career never cease to end. They usually present in different forms, most often as self-reflecting questions the working-class subconsciously ask themselves every day… Man, what am I doing with my life? I just have to get to the weekend! I hate my job but my kids need food on the table. According to Che Guevara, capitalism moves people away from expressing their interests without even knowing it.[1] And even beyond alienating people from their interests, the interrelation between a person’s ability to produce, save, and organize[2], which are vital elements of a revolution, are also damaged under capitalistic systems. People are disconnected from their labor because even if they are working in a field they are interested in, capitalism separates the individual from the products of their labor and likewise, disconnects them from their sense of self and purpose. Martizen-Sanez writes, “The distinction that people experience between communal interests and individual interests arose because in capitalist society, human beings lacked the control of the distribution of the products of their labor and were treated as a means to an end rather than an end; their relations were reduced to purely economic relations, and the difference between an animal and a human existence had become unintelligible” (Martinez-Saenz, 24). This alienation under a capitalist system is something Marx and Guevara shared in concern. If the individual is alienated because of oppressive external conditions under capitalism, then the individual will inevitably lose touch with self. So, not only are workers frustrated with the inability to reap the fruits of their labor but they are forcibly stripped of any identity of selfhood. Marx talks of this exact same issue in his manuscript Alienated Labor. Petrović writes of this when considering Marx, stating, “The alienation of the results of man's productive activity is rooted in the alienation of production itself. Man alienates the products of his labor because he alienates his labor activity, because his own activity becomes for him an alien activity, an activity in which he does not affirm but denies himself, an activity which does not free but subjugates him. He is home when he is outside this activity, and he is out when he is in it” (Petrović, 241). Labor becomes alien to the worker who is completely disconnected from their work. Yet perhaps even worse than Marx could have predicted, “home,” where “he is outside this activity” is arguably no longer even a space where his selfhood can be reconnected in the United States. Labor has not only alienated the worker from his work but has created such extreme conditions that almost all spaces are now alienating in this country. Marx and Guevara weren't the only ones to recognize the divide capitalism causes between labor and passion, capital and self. W.E.B. Du Bois, Huey Newton, and Paul Robeson all observed not only the social differences in the Soviet Union and Mao’s People’s Republic of China, particularly related to race, but also the differences in how the working people of these places viewed and digested their labor. While we can obviously recognize the differences in their ability to reap the fruits of their labor compared to US workers (or any workers under capitalism or neoliberalism), less often do we examine the psychological relationship a Marxist revolution enables. The psychological relationship being the connection one has between his labor and his selfhood. Du Bois immediately recognized the safety and welcome he felt when he visited the Soviet Union. Yet, even beyond those social changes, he was also able to observe a new dynamic among the working people. “Du Bois applauded the Soviet program, which had made of the working people of the world ‘a sort of religion,’ a form of scientific idealism he posited as being indispensable to progress” (Carew, 54). The Soviets were dedicatedly connected to their work— producing historically groundbreaking results (we mainly consider the scientific ones), but they also psychologically pushed an entire population onwards with the same unifying intensity exhibited in religion. Du Bois’ idea that work can create a motivating spirit in the people is something he also observed in China: “Du Bois saw ‘a fable of disciplined bees working in revolutionary unison. Cataloging the public places, restaurants, homes of officials, factories, and schools visited,’ he saw only ‘happy people with faith that needs no church or priest’” (Carew, 61). Once again we have this reference to a sense of drive, pride, and motivation so unifying that it is comparable to the togetherness brought on by religion. Workers had faith in their labor and therefore did not struggle with the questions that I examined earlier in this piece. Work in Marxist societies erases the disconnect that laborers otherwise have between their selfhood and work-life in capitalist systems. Huey Newton also observes the connection between selfhood and labor that America lacks when he visited The People’s Republic of China: “While there, I achieved a psychological liberation I had never experienced before. It was not simply that I felt at home in China; the reaction was deeper than that. What I experienced was the sensation of freedom as if a great weight had been lifted from my soul and I was able to be myself, without defense or pretense or the need for explanation. I felt absolutely free for the first time in my life-completely free among my fellow men. This experience of freedom had a profound effect on me, because it confirmed my belief that an oppressed people can be liberated if their leaders persevere in raising their consciousness and in struggling relentlessly against the oppressor… To see a classless society in operation is unforgettable. Here, Marx’s dictum— from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs— is in operation” (Newton, 348, 352). Again, Newton mentions this psychological liberation that is almost spiritual or religious in nature. The societies that America paints as those in which people are forced to work for “hours without reward,” in reality actually provide a sense of freedom and liberation for one's selfhood through Marxist labor structures, the antithesis to everything we’re told in school. Yet it cannot be a coincidence that all of these African-American revolutionaries observed such similar feelings of liberation. Undoubtedly, the widespread feeling of disconnect that I described earlier in America’s working culture, is the exact opposite in cultures that have experienced Marxist revolutions. In places where Marxist revolutions have occurred, a feeling of intense connection to one’s labor arises. Du Bois and Newton do not speak of the mysticality of an un-alienated society randomly. Petrović also accounts for the same role the rejection of alienated labor has in a spiritual setting: “In this sense, Marx… speaks about communism as a society which means ‘the positive supersession of all alienation and the return of man from religion, the family, the state, etc., to his human, i.e., social life (existence)’” (Petrović, 424-425). If alienation between a worker and his work is ended, he will be able to return to his truest human condition and existence. In the same sense that Du Bois and Newton observed, ending alienation in labor, returns the man to his truest self. Paul Robeson, a local hero for my fellow Princeton, New Jersey residents, found this connection so powerful (that along for obvious social reasons) he moved his family to the Soviet Union for a period of time.[3] This reinforces the notion that Marxist revolutions create spaces for marginalized people to not only experience less racial prejudice than in the States, but also a complete liberation of selfhood. A liberation that can remove the constraints of not only racial oppression, but of the realities that all working class people experience in the United States: the inevitable disconnect between selfhood and work, or labor-alienation, that is inevitable in capitalist-based systems. Che Guevara’s idea of the “new man,” is the alternative that American workers need. In America’s capitalist hellscape, not only are adult workers disconnected from the fruits of their labor and individual sense of belonging and purpose, but the youth population is as well. We tell our youth they have to work to survive, but when they produce the tools of their survival they are completely stripped of the fruits themselves. Instead, the products of their labor go to the bourgeoisie so that this system can continue. And not only are people physically disconnected from the products of their labor, but they are psychologically disconnected from their labor as well. This makes it nearly impossible to love or find meaning in one’s job, regardless of one’s theoretical interest. Instead, American workers work only to put food on their families’ “tables” (arguably the vicious cycle doesn’t even allow that). It's a twofold issue that creates a never-ending cycle that is intentionally impossible for the working-class American to escape. Make the working-class person work a job that only gives him enough to keep him in an endless cycle of crises until he no longer love his work and can no longer love himself. Yet if we have a revolution in this country, if our workers are able to embody Guevara’s vision of the “new man,” the connection between laborer and labor can be reformed. Martinez-Saenz quotes Guevara who said, “The relation of economic controls to moral incentives is more subtle than indicated. Moral incentives, if they are truly the individual’s incentives, cannot be directed from above. That is why the many Cubans ask, ‘How can you plan voluntary work? Is this not a contradiction in terms?’ What types of economic controls are compatible with a system of moral incentives? Recognition of this issue has emerged in two forms. First, an understanding that moral incentives are directly related to the level of education and the nature of one’s employment, and this is reflected in Cuba’s intensive educational effort, particularly in technical training. Second, experimentation with a new worker organization and system of emulation whose aim in part is to stimulate greater participation and eliminate bureaucratic controls” (Martinez-Saenz, 22). Guevara clearly lays out these two steps that are important to understand in order to truly alleviate the disease of worker alienation. America, however, is nowhere close to adopting the steps Guevara saw for the people of Cuba: a revolution must take place first. This issue, therefore, is actually deeper than just a singular failure of capitalism. We know that it will be the working-class that unites to create a revolution in this country. Here we see the perfect connection: it is a working-class issue that can only be alleviated by the working-class themselves. It will take a revolution led by the working class to instate a positive relationship between workers and work. The myth of the “American Labor Shortage” shows the dissatisfaction the working class has with the exploitation of their labor. Now, more than ever, the working class must band together to revolutionize a system that does not work for them. To not only create a place where they can reap the fruits of their labor, but where workers can love their work and reject alienation. [1] Martinez-Saenz, Miguel. “Che Guevara’s New Man: Embodying a Communitarian Attitude.” Latin American Perspectives 31, no. 6 (November 1, 2004): 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X04270639. (pg 21). [2] Martizen-Saenz, 21 [3] Carew, Joy Gleason. Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008. muse.jhu.edu/book/6044. Work Cited Carew, Joy Gleason. Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008. muse.jhu.edu/book/6044. Martinez-Saenz, Miguel. “Che Guevara’s New Man: Embodying a Communitarian Attitude.” Latin American Perspectives 31, no. 6 (November 1, 2004): 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X04270639. Newton, Huey P., and Fredrika Newton. Revolutionary Suicide: Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Classics, 2009. Petrović, Gajo. “Marx’s Theory of Alienation.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 23, no. 3 (1963): 419–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2105083. AuthorElla Kotsen is an undergraduate student at Bryn Mawr College. She is majoring in English and double minoring in History and Growth & Structure of Cities. She plays Division III women’s basketball and has received Centennial Conference Academic Honors. Her main subject of interest is in geopolitics and understanding the historical implications of colonization in Latin American countries. She is interested in Marxist literary theory and enjoys the work of Fanon, Eagleton, and Althusser. Ella also writes for her own independent blog where she produces opinion pieces, book reviews, and audio-based interviews. This article was republished from the Youth league. Archives January 2022 Sean O’Brien (right), leader of New England Joint Council 10, campaigned at plant gates. O'Brien and the Teamsters United slate have clinched a victory. It’s the first time in almost a quarter-century that a coalition backed by Teamsters for a Democratic Union has taken the driver’s seat in the international union. This article was updated November 19 to reflect the final election results. A new administration will soon take the helm of the 1.3 million-member Teamsters union. The Teamsters United slate swept to victory in this week's vote count, beating out their rivals 2 to 1. It’s the first time in almost a quarter-century that a coalition backed by Teamsters for a Democratic Union has taken the driver’s seat in the international union. The incoming president is Sean O’Brien, leader of New England Joint Council 10. He says his top priorities are to unite the rank and file to take on employers, organize Amazon and other competitors in the union’s core industries, and withdraw support from politicians who don’t deliver on union demands. Essential to organizing at Amazon or anyplace else, O’Brien argues, is winning enviable contracts for the existing Teamsters. “Our biggest selling point to potential members is showing in black and white what a union contract can do,” he said. “We’ve got to have a grassroots campaign to engage our members working in similar industries and showcase what Teamsters can do—and that means negotiating strong contracts that people want to be part of.” In UPS negotiations in 2023, he says, the union must abolish the second tier of drivers, raise the starting pay of part-timers from $14 an hour to $20, and crack down on subcontracting and Uber-like deliveries by “personal vehicle drivers.” He and his running mates have pledged to strike UPS if necessary. Five years ago, O’Brien won an Eastern region vice president spot on the incumbent slate of longtime President James P. Hoffa, who is retiring this year. But in 2017, Hoffa fired him as package division director after O’Brien insisted the UPS bargaining team should include opposition leader Fred Zuckerman, president of Local 89 in Louisville, who had led the 2016 Teamsters United ticket that nearly toppled Hoffa. Now Zuckerman will take the number two seat as secretary-treasurer. Teamsters United has won a controlling majority on the union’s 27-seat international executive board. WAVE OF FURY

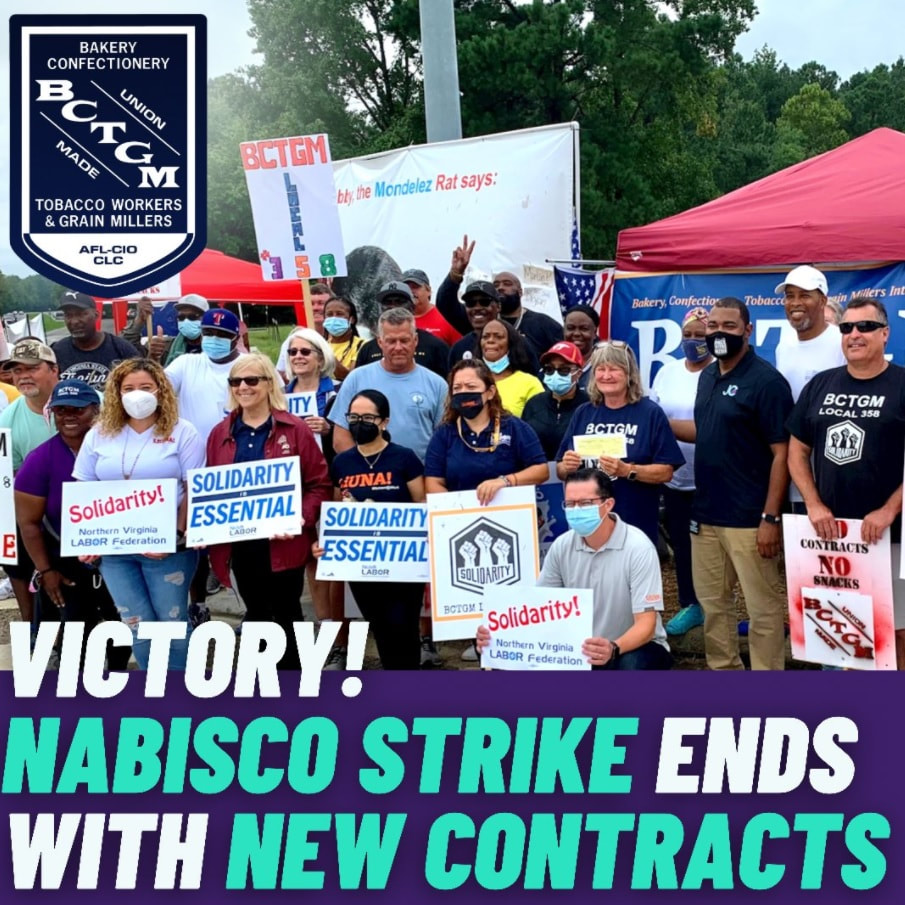

NOW THE HARD PARTIt took years of organizing to get here. But the bigger task is what comes next—not just pointing to the problems confronting the union, but tackling them. “We have to right the ship,” said John Palmer, a current Southern region vice president who will become an at-large vice president. (In 2016 Teamsters United won in two regions, giving the coalition six seats on the union’s executive board.) “It takes many, many miles to turn a battleship around in the middle of the ocean, and that’s what we have to do here.” “If you want change, you have to change,” said Local 572 steward Frank Halstead, a Los Angeles grocery warehouse worker and TDU steering committee member. “The structure determines effectiveness. They’re going to have to reallocate money.” For instance, rather than continue padding officers’ salaries with multiple titles, he wants the union to hire energetic full-time division representatives who can help locals in the same industry build a strategy to coordinate their bargaining, raise standards, and fight threats like automation. “Under the current administration there are no full-time warehouse division reps,” Halstead said. “You have officials from certain locals who hold that title, but they can’t do two jobs; you can’t be a business agent at a local and a division rep. That’s the kind of stuff that has to stop.” The organizing department needs restructuring too, said Palmer, who worked there for years. “We waste a tremendous amount of money flying organizers around the country,” he said. “That time and resources could allow us to train people out of locals to do this. We need to have that skill on the ground everywhere; we don’t need a lot of specialists airdropped from D.C. who disappear the minute a campaign is over.” UPS STRIKE IN 2023? August 2023, when the UPS contract expires, isn’t as far away as it might sound. “A contract campaign basically needs to start on day one,” said Chicago Campaign Coordinator Dave Bernt, another TDU steering committee member. “We need to have a national coordinated contract campaign to get members engaged, to use their engagement as leverage in negotiations.” Making the strike threat more than a bluff starts with “basic communication,” Bernt said. He means headquarters should use methods like texting and social media to inform the 320,000 UPS Teamsters of the timeline and what’s at stake. But he also means member-to-member: “Just as we campaigned for office, we need to have members go out to their gates and engage their membership, talk about the issues and talk about how to prepare for negotiations. Start socking away money; don’t make any major purchases.” Braswell agrees: It’s time to encourage members to put away $20 or $50 each pay period, and to make the word “strike” more familiar, less scary. (The union also has a strike fund of more than $300 million that hasn’t been used in decades, O’Brien says—and he plans to put it to use.) “UPS, they’ve had a free ride for the past 23 years,” Braswell said. “They didn’t have to take us seriously when we came to the negotiations table. That’s going to change.” NOT JUST AMAZONOrganizing Amazon will be a “massive long-term task,” Palmer said. “It’s going to require the help of religious groups, community groups, environmental groups, and other unions. We have to have a really deep, well-thought-out strategy.” But other targets are in closer reach: industries and companies where the Teamsters already represents part of the workforce, and could gain leverage by organizing more. “In the waste industry we have New York, Chicago, L.A. with relatively high density,” Bernt said, “but we have whole areas particularly in the South where we represent hardly any waste workers, [even though these are] companies we already have contracts with.” Grocery warehouses are another example. The Teamsters represent some Costcos and some Krogers. “Why not all?” Halstead said. “With those numbers comes increased strength, increased resources. Then you can start to think about going after the Amazons and these giants.” TDU: HERE TO STAYWhat happens to an opposition group like TDU when it’s in coalition with the leadership? “It’s a lot less complicated than people think,” Bernt said. “Our strategy, I think, will continue to be the same. Our goals are to build union power through engaging the rank and file in fights against the bosses. That’s been our goal when we were in the opposition, and that’ll continue to be our goal as we’re part of a coalition that’s running the union.” TDU leaders argue the union needs more leaders coming up from below. It’s TDU’s mission to encourage and train them. O’Brien said the campaign had proven the value of the coalition behind it. “I love the relationship, and I’ve committed we are going to work hand in hand moving forward,” he said. “TDU, Teamsters United, and all Teamsters are going to play a significant role in policy-making in the International. I always told people—I grew up Irish Catholic, and there were always disagreements around that dinner table. But reasonable people will find reasonable solutions for reasonable problems.” “I’m just excited,” Braswell said before the vote count began. “I’m at the end of my career here. When I first came in, they taught us, ‘When you leave here, you need to leave it in better shape than what you found it.’ It was always my fear because of Hoffa I was going to leave my union and it was going to be a total mess. But I see a light at the end of the tunnel. “In my small way I contributed to it. I did my part. I left my union in a better place.” Jonah Furman contributed reporting to this article. AuthorAlexandra Bradbury is the editor of Labor Notes. [email protected] This article was produced by Labor Notes. Archives November 2021 10/25/2021 'Let's Put a Wrench in Things Now': Deere Workers Strike as Company Rakes in Record Profits. By: Jonah FurmanRead NowMembers of UAW Local 74 at John Deere's Ottumwa Works are among 10,000 workers on strike at the farm equipment maker. Photo: Chris Laursen Ten thousand John Deere workers in Iowa, Illinois, and Kansas launched an open-ended strike October 14. The strike came after workers overwhelmingly voted down a first tentative agreement negotiated by the Auto Workers (UAW). Among the over 90 percent of members voting, 90 percent voted no. Members’ frustrations ranged from inadequate wage increases to an end to the pension for new hires, switching to a “Choice Plus” plan that many felt was scant on details. And they feel emboldened by a tight labor market and pandemic-related parts shortages that have made it hard for Deere to build up inventory. At Deere’s Tractor Cab & Assembly Operations in Waterloo, Iowa, the 8000 tractor line—which workers refer to as the “money-maker”—was already over 800 units behind schedule at the start of the strike, according to Dana Thibadeau, a third-shift steward. That line produces tractors that can cost up to $800,000. “When you factor in the pandemic, being deemed essential workers, and in our case, having a company turning a record profit, the CEO giving himself a 160 percent raise, and giving a 17 percent dividend raise, we kinda feel like we’re left to kick rocks,” said a UAW member at Iowa's Davenport Works who asked for anonymity for fear of retaliation. Deere is in the midst of its most profitable year ever. The farm and construction equipment manufacturer expects to rake in $5.7 to $5.9 billion in net income this year, far exceeding its previous high of $3.5 billion in 2013. This is the first strike for nearly all current Deere workers, though some recall walking the picket lines with their parents and grandparents during the last Deere strike, a five-month walkout that began in 1986. GOT TO SEE THE CONTRACTA tentative agreement was initially announced October 1, hours after the contract expiration was extended. Members had been expecting to strike that night, and many were frustrated with an agreement that they felt would just allow Deere to build up more inventory before a potential strike. Workers have long been dissatisfied with the union’s secretive bargaining process. The last contract, in 2015, passed by fewer than 200 votes. Many members were frustrated at the time that they only got to see the details—in a highlights document—during their two-hour ratification meetings. “Everything is always a damn secret with them,” said Trever Bergeron, an iron pourer with Local 838 at the Waterloo foundry. “We are the last thing they think about.” Since then, according to Chris Laursen, former president of Local 74 in Ottumwa, Iowa, some local presidents had pushed amendments at the UAW’s Deere Council (made up of all the Deere locals) to guarantee that members would get to see the full contract—not just highlights—well in advance of the vote. Laursen himself put forward a resolution in 2019 to release the contract at least a week before a ratification vote. It failed, but eventually, a motion was passed guaranteeing members would get to see the contract three days ahead. Members also got to hear the company’s initial offer, which contained a host of concessions, at strike authorization meetings in September. Deere proposed ending the plant closure moratorium, doing away with overtime pay after eight hours, eliminating seniority-based wage progressions, forcing workers to pay 20 percent of their health insurance premiums, and many other draconian concessions. “That was a slap in the face,” said the Davenport member. “Some company folks were trying to rationalize it: this is just the first offer, you never accept the first offer. If someone were selling a home for $160,000, and your first offer was $40,000, that would break down the good-faith negotiations.” Members voted 99 percent to authorize a strike. A THIRD TIERDeere backed down from most of these concessions at the bargaining table. The agreement members rejected on October 14 would have maintained the current premium-free health insurance plan. It also would have reinstated the cost-of-living adjustment, which was eliminated in the previous contract. But it introduced a new major concession: no pensions for new hires. Deere already has two tiers of workers: “pre-97” and “post-97.” In 1997, Deere lowered wages, health care benefits, and pensions for all new hires and eliminated their post-retirement health care. This division of the workforce has for many defined their work experience; the most active hub of rank-and-file communication is the “Post 97” Facebook group. Many of those hired after 1997 have long hoped to win back retiree health care. The tentative agreement would have created a third tier, a concession many workers are unwilling to accept. “We’ve been fighting against this pre-97, post-97 bullshit for years,” said Thibadeau. “And then we're going to do it again? To the new hires? What on earth?” NOT ENOUGHThe new tier wasn’t the only clause that got members fired up. The tentative agreement included an 11 percent raise over six years, including a 5 percent raise in year one. In 2022, 2024, and 2026, workers would have received 2 percent lump sums instead of wage increases. That wasn’t enough for most Deere workers, who are fed up with watching the company’s profits, dividends, and executive pay soar while their own wages stagnate. “Maybe it looks like, ‘Hey, five percent seems somewhat reasonable, but it’s just over a dollar an hour, and it’s comparable to what people in 1997 were making,” said Brad Lake, a 14-year Deere employee with Local 838. Under the 2012 contract, pre-1997 hires in the most common pay grade were making a base wage of $20.86. In the current offer, the company is offering post-1997 hires in the same pay grade a base wage of $20.80, nine years later. At the ratification meeting in Milan, Illinois, Local 79 education chair Dave Parkin emphasized the divergence between the company’s profits and workers’ incomes: “In 1997, Deere reported a net income of $817 million. In 2021, they are projected to make $5.7 billion.” Meanwhile, the starting wage at Deere has gone from just under $15 in 1997 to just over $20 in the current offer. “While Deere profit has grown almost 700 percent since 1997, our buying power has shrunk by 35 percent,” Parkin told members. In a flyer distributed at the plants just before the strike, headlined “Making the Best Wages BETTER,” Deere claimed that workers typically make $60,000 a year, and that the new contract would bring workers up to almost $72,000 per year. But that figure assumes year-round full-time work—ignoring Deere’s common seasonal layoffs, which can range from weeks to months. Workers’ compensation is also dependent on a complicated piece-rate system known as the “Continuous Improvement Pay Plan” (CIPP, pronounced “kip”). Deere’s figure assumes that workers are performing at a rate of 120 percent of the target set by management—but many departments are failing to reach their quotas, given parts shortages and the fact that management wants productivity to increase by 2 percent every six months, making targets harder to hit. One worker shared their annual pay with Labor Notes: they made less than $40,000 in 2020, and have worked at the company for over a decade. For some, CIPP provides big payouts that can take workers past the $60,000 figure. But many see little to no CIPP money at all. “What you can potentially make on paper versus what is guaranteed and what you come home with are three different numbers,” said the Davenport member. CALL AN AMBULANCEDeere is attempting to run the plants with salaried employees—some engineers but many white-collar office workers as well. According to one of these workers, some had to buy steel-toed boots in preparation for their strikebreaking deployment. Just hours into the strike, an ambulance had already been called at the Drivetrain Operations in Waterloo. At the Tractor Cab and Assembly Operations across town, a salaried worker crashed a tractor into a pole on the first day. In Coffeyville, Kansas, members on the picket line reported hearing alarms repeatedly going off in the plant, and it was rumored that a salaried employee attempting to operate the furnace had been calling members and retirees for advice. White-collar Deere workers, who are not union members, have their own gripes. Deere cut hundreds of salaried jobs in 2020 and forced some of the remaining employees into lower pay grades and contractor status, according to salaried workers. Now, hundreds of these workers find themselves working 12-hour days, six days a week, in jobs they are not trained for and did not sign up for. About 650 were reassigned to the Parts Distribution Center in Milan, Illinois. “If Deere wanted to piss off all of their employees simultaneously, they've done a very good job of doing so,” one white-collar worker wrote to Labor Notes. PICKET LINESSince they went on strike, members have been maintaining 24/7 picket lines. Locals have printed shirts that read “DEEMED ESSENTIAL IN 2020. PROVE IT IN 2021. CAN’T BUILD IT FROM HOME.” On October 18, the strike's fifth day, several locals made a push for large morning pickets. In Waterloo, members reported a three-hour backup of salaried workers and management employees attempting to cross the line; in Davenport, two and a half hours. A mass “show of force” last night by Local 865 at Deere’s Harvester Works in East Moline, Illinois, drew 1,000 picketers and stretched for 15 blocks, according to one striker’s estimate. Wall Street sounds worried. Bank of America’s analysis on day one of the strike was headlined, “Deere likely has limited appetite for extended strike.” Workers were conscious of the financial implications as well. “The fiscal year for Deere ends October 31, so this puts a real cramp on them at the end of the quarter and end of the year.” said Lake. “That was a huge issue of why we wanted to do it now. Because if we give them another extension they’re going to finish out their fiscal year, and this’ll be all on their 2022 books, so let’s put a wrench in things now.” “The quicker we can put a financial dent on them, the better off we are when it comes to showing them that we mean business,” said the Davenport worker. BIGGEST DEALThe company plans to cut off workers’ health insurance by the end of October. The UAW, which has a $790 million strike fund, is picking up COBRA payments and providing strike pay of $275 per week. The union and Deere resumed negotiations this week. The Deere contract is the biggest deal negotiated by the UAW since the resignation of President Gary Jones over corruption charges in November 2019. Former Vice President Norwood Jewell, who led bargaining on the last Deere contract, was sentenced to 15 months in prison for taking illegal payments from Fiat Chrysler. While there’s been no evidence connecting the Deere negotiations to the corruption scandal, many members mistrust the International. Yesterday, the UAW’s 400,000 active members and 600,000 retirees began voting in a mail-ballot referendum on whether to move to direct elections for the union’s top officers, rather than the delegate system that has maintained one-party control over leadership positions for the past seven decades. Anger over two-tier contracts and secretive bargaining will impact that vote. UAW members with the Unite All Workers for Democracy reform group, who are pushing for a “yes” vote in the referendum, organized a solidarity fund to bring supplies to the Deere picketers. In the first 24 hours, they raised $45,000 from supporters. For updates on the strike, follow @JonahFurman on Twitter. AuthorJonah Furman is a staff writer and organizer for Labor Notes.[email protected] This article was produced by Labor Notes. Archives October 2021 Image: Jared Cummings, Kellogg Union Members Appreciation Page (Facebook). The class struggle is sharpening. Workers all across the country are striking and engaging in other job actions, large and small. Fed up with company attempts to impose two-tier wages, long hours, and inadequate pay, despite rising productivity and skyrocketing corporate profits, unions in several industries have had it. Now they’re marching on the picket lines. As late as last weekend, over 100,000 workers had voted to authorize strikes, and over 169 have occurred so far this year, the largest uptick since the wave of job actions in 2018–19. The AFL-CIO has aptly labeled this month #striketober. There is deep anger, unrest, and growing militancy among the working class. Why? Companies want more while labor is repeatedly asked to do with less. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that “manufacturing sector labor productivity increased 8.0 percent in the second quarter of 2021, as output increased 5.5 percent and hours worked decreased 2.3 percent.” Overall, productivity “grew an average of 3 per cent in the first half of 2021. Unit labour costs fell 0.8 per cent during the same period.” But at what cost to the worker? Wages are too low to pay for the rising cost of housing, hours are too long to allow adequate time for caregiving, and lack of health care benefits force many to go to work sick. Workers are tired of supplying profits to billionaires like Jeff Bezos to fuel their rocket rides and egos. As the nation emerges from the pandemic, literally millions are so dissatisfied that they’re simply quitting in what some have described as a silent general strike. “The seriousness of the situation was confirmed by the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics report showing that a record 2.9 percent of the workforce quit their jobs in August, which is equivalent to 4.3 million resignations.” According to one poll, ”employees were so dissatisfied with their situation that more than one-quarter (28%) of all respondents left their jobs without another job lined up.” One of the main reasons workers are leaving is burnout, cited by 40% of the poll respondents. Big business is alarmed at the political significance of the resignations. The “Great Resignation,” Forbes writes, “is a sort of workers’ revolution and uprising against bad bosses and tone-deaf companies that refuse to pay well and take advantage of their staff.” Contributing to the spike in labor activism is growing confidence in collective action and knowledge that you can strike and win. A glut in job openings despite still significant unemployment has improved the unions’ bargaining position and power. Pro-union sentiment among the broad public is at its highest level in several decades. A Gallup poll released in the beginning of July showed that 68% of Americans approve of labor unions, up significantly from the 48% approval in 2009 during the throes of the Great Recession. In this regard, the Biden-Harris administration’s pro-union stance should not be underestimated, not the least of which is reflected by new appointments to the National Labor Relations Board. The new general counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, for example, has “signaled that she is willing to reconsider all kinds of twisted and outdated precedents that have vastly favored bosses during a nearly four-decades-long union-busting drive . . . she’s indicated a willingness to issue bargaining orders — not elections — for new unions when employers commit Unfair Labor Practices, to certify minority members-only bargaining units to help unions establish a foothold, and to be more creative about ‘make whole’ financial remedies for terminated union activists.” As Peoplesworld.org reports, 10,000 workers at John Deere are among the latest to go out: “The strike wave that has hit John Deere has been building nationwide for more than a month. Last week Kellogg workers went on strike and over the summer Mondelez, the maker of Nabisco Oreos walked out. Coal miners in Alabama have been on strike for months.” While uneven, the working class and people’s forces in local communities and workplaces are gathering in strength for the class and democratic battles that lie ahead. Today they’re focused on bread-and-butter issues of survival. But with the GOP blocking everything from strengthening voting rights to spending on climate change and human infrastructure, these economic struggles are becoming political. When that material force takes off and as the mid-terms loom — watch out. Big days are coming. But it’s a mistake for friends of labor to sit around awaiting their arrival. Visit the picket lines and be sure to bring your walking shoes. A box of donuts and coffee would be appreciated but more important are the smiles and solidarity of friends. Talk, learn, listen, and afterwards share the experience. In so doing you’ll add to the growing class-consciousness and militancy that’s sweeping the nation. It will do everyone concerned a whole lot of good. Building community support for striking workers is vital, calling on local politicians, clergy, and neighborhood leaders to lend solidarity. Letters to the editor along with social media campaigns can help build pro-strike sentiment. Community pickets at retail outlets and dealerships might also be helpful. Solidarity should also include boycotts and other forms of public pressure against companies that refuse to provide good wages, health care, working conditions and rights in the workplaces. Yes, there’s a rising tide of struggle occurring deep within our class. Let’s give it our every support. AuthorJoe Sims is co-chair of the Communist Party USA (2019-). He is also a senior editor of People's World and loves biking. This article was produced by CPUSA. Archives October 2021 Members of BCTGM Local 364 on the picket line earlier in September. They were joined by progressive Oregon Congressman Earl Blumenauer, standing third from left. | Donnajo Calhoun-Marks / via BCTGM PORTLAND, Ore. —You can buy and eat Oreo cookies again. Just make sure they’re made in the U.S.A., especially in Portland, Ore., not in Monterrey, Mexico. The reason we specify Portland is it’s where Mondelez workers, at that Nabisco cookie and snack plant, fed up with company refusal to bargain a new and better contract at a time of record earnings, started what became a national walkout by the firm’s workers, all Bakery, Confectionery and Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers (BCTGM) members. Key issues were not just raises, but working conditions. Those sometimes included back-to-back 12-to-16-hour shifts, BCTGM said. The workers at the firm’s five U.S. snack plants, including Portland and Chicago, didn’t get all they wanted, but they got a lot from the firm and overwhelmingly ratified the contract, said union President Anthony Shelton. “This has been a long and difficult fight for our striking members, their families, and our union. Throughout the strike, our members displayed tremendous courage, grit, and determination,” he said Sept. 18.