|

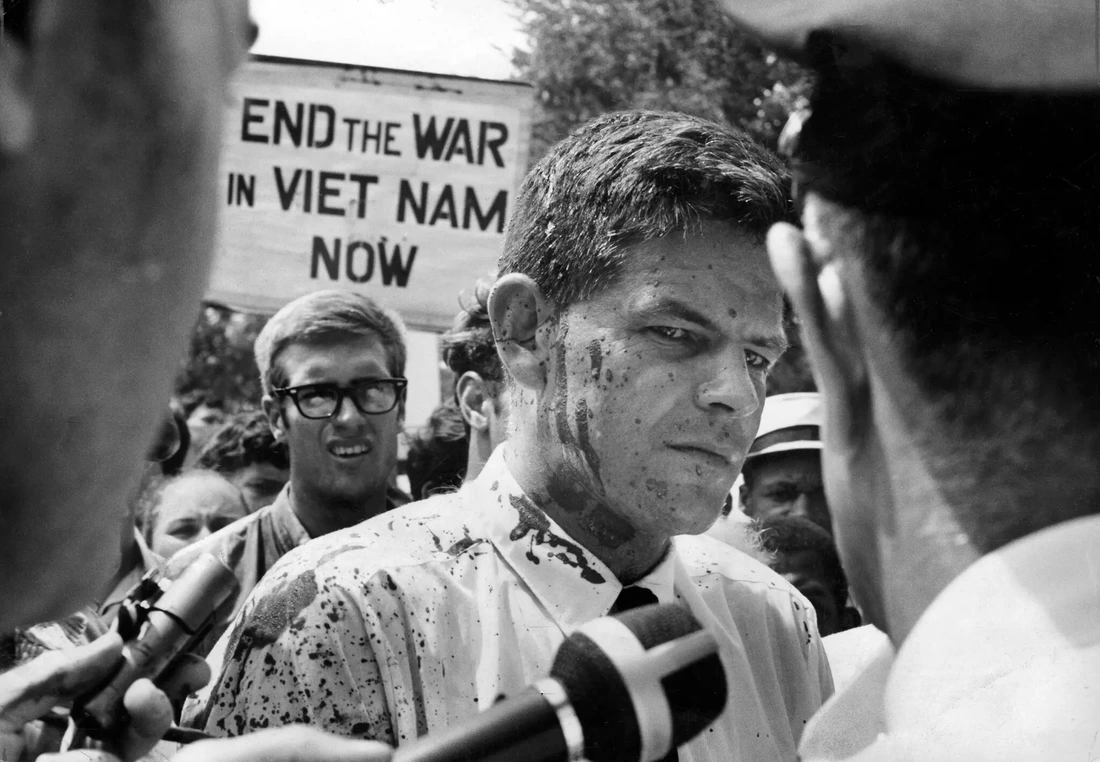

12/20/2022 Staughton Lynd: Thinking history, doing politics, from below By: Julius GavrocheRead NowWhat we are about is a new set of values, the practice of solidarity. Capitalism developed within feudalism as the practice of the idea of contract. What was imagined was a society in which free and equal members of civil society would enter into mutually binding agreements. Thus, the free city. Thus, the guild of artisans. Thus, the congregation of Protestant believers bound together by a “covenant” (a different kind of contract). And thus, the capitalist corporation, its investors, its shareholders. Of course, the reality was and is that the parties to capitalist labor contracts were and are not equal, and therefore the ideological hegemony of the bourgeois idea of contract has always been and still is based on a sham. Counter-hegemonically, we practice solidarity. Solidarity might be defined as drawing the boundary of our community of struggle as widely as possible. When LTV Steel first filed for bankruptcy in 1986, Youngstown retirees debated whether they should seek health insurance only for steel industry retirees or for everyone. They decided, for everyone. When LTV Steel recently filed for bankruptcy a second time, the United Steelworkers of America made the opposite choice: they asked Congress to subsidize the so-called “legacy costs” of the steel industry, not for universal health care. Staughton Lynd, ¡Presente! People’s historian Staughton Lynd died on Nov. 17 after an extraordinary life as a conscientious objector, peace and civil rights activist, tax resister, professor, author, and lawyer. Lynd inspired us with his role as a people’s historian, always working in solidarity with struggles for justice today. Lynd served as director of the Freedom Schools in the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project. He worked with prisoners and challenged the prison-industrial complex. While teaching at Spelman College, his family and Howard Zinn’s developed a lifelong friendship. Zinn said of Lynd, “He is an exemplar of strength and gentleness in the quest for a better world.” Among Lynd’s many books is Doing History from the Bottom Up, in which he described three key perspectives that are guides for any teacher or student of history. 1. History from below is not, or should not be, mere description of hitherto invisible poor and oppressed people: it should challenge mainstream versions of the past. 2. The United States was founded on crimes against humanity directed at Native Americans and enslaved African Americans. 3. Participants in making history should be regarded not only as sources of facts but as colleagues in interpreting what happened. After Freedom Summer, Lynd got involved in anti-Vietnam War organizing. Despite his talents as a scholar, academia closed their doors to him after he traveled on a fact-finding mission to Hanoi. In a 2013 essay about Lynd, Andy Piascik explains what happened next: Lynd never looked back. He became an accomplished scholar outside the academy and one of the most perceptive and prolific chroniclers of “history from below,” with a special interest in working class organizing. From a series of interviews, he and [his wife] Alice produced the award-winning book Rank and File, which begat the Academy Award-nominated documentary film Union Maids. In a memorial tribute to Howard Zinn at the Organization of American Historians, Lynd said, “When a comrade dies in the struggle for nonviolent revolution, we try to pick up his dreams.” May we all do that now: pick up Lynd’s dreams and his principled, grassroots approach to making those dreams a reality. Remarks on Solidarity UnionismSpeech at the 2005 IWW Centenary in Chicago, Illinois To Begin With The greatest honor I have ever received is to be asked to speak to you on the occasion of the IWW’s 100th birthday. But I am not standing here alone. Beside me are departed friends. John Sargent was the first president of Local 1010, United Steelworkers of America, the 18,000-member local union at Inland Steel just east of Chicago. John said that he and his fellow workers achieved far more through direct action before they had a collective bargaining agreement than they did after they had a contract. You can read his words in the book Rank and File. Ed Mann and John Barbero, after years as rank and filers, became president and vice president of Local 1462, United Steelworkers of America, at Youngstown Sheet & Tube in Youngstown, and toward the end of his life Ed joined the IWW. Ed and John were ex-Marines who opposed both the Korean and Vietnam wars; they fought racism both in the mill and in the city of Youngstown, where in the 1950s swimming pools were still segregated; they believed, as do I, that there will be no answer to the problem of plant shutdowns until working people take the means of production into their own hands; and in January 1980, in response to U.S. Steel’s decision to close all its Youngstown facilities, Ed led us down the hill from the local union hall to the U.S. Steel administration building, where the forces of good broke down the door and for one glorious afternoon occupied the company headquarters. Ed’s daughter changed her baby’s diapers on the pool table in the executive game room. Stan Weir and Marty Glaberman, very much alone, moved our thinking forward about informal work groups as the heart of working-class self-organization, about unions with leaders who stay on the shop floor, about alternatives to the hierarchical vanguard party, about overcoming racism and about international solidarity. These men were in their own generation successors to the Haymarket martyrs and Joe Hill. They represented the inheritance that you and I seek to carry on. How I First Learned About the IWW It all began for me when I was about fourteen years old. Some of you may know the name of Seymour Martin Lipset. He became a rather conservative political sociologist. In the early 1940s, however, he was a graduate student of my father’s and a socialist, who wrote his dissertation on the Canadian Commonwealth Federation. Marty Lipset decided that my political education would not be complete until I had visited the New York City headquarters of the Socialist Party. The office was on the East Side and so we caught the shuttle at Times Square. I have no memory of the Socialist Party headquarters but a story Marty told me on the shuttle changed my life. It seems that one day during the Spanish Civil War there was a long line of persons waiting for lunch. Far back in the line was a well known anarchist. A colleague importuned him: “Comrade, come to the front of the line and get your lunch. Your time is too valuable to be wasted this way. Your work is too important for you to stand at the back of the line. Think of the Revolution!” Moving not one inch, the anarchist leader replied: “This is the Revolution.” I think I asked myself, Is there any one in the United States who thinks that way? A few years later, in my parents’ living room, I picked up C. Wright Mills’ book about the leaders of the new Congress of Industrial Organizations, The New Men of Power. Mills argued that these men were bureaucrats at the head of hierarchical organizations. And at the very beginning of the book, in contrast to all that was to follow, Mills quoted a description of the Wobblies who went to Everett, Washington on a vessel named the Verona in November 1916 to take part in a free speech fight. As the boat approached the dock in Everett, “Sheriff McRae called out to them: Who is your leader? Immediate and unmistakable was the answer from every I.W.W.: ‘We are all leaders’.” So, I thought to myself, perhaps the Wobblies were the equivalent in the United States of the Spanish anarchists. But here a difficulty held me up for twenty years. If, as the Wobblies seemed to say, the answer to the problems of the old AF of L was industrial unionism, why was it that the new industrial unions of the CIO acted so much like the craft unions of the old AF of L? Industrial Unionism and the Right to Strike The Preamble to the IWW Constitution, as of course you know, stated and still states: The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry …. Clearly these words, when they were written, referred to a workplace at the turn of the last century where each group of craftspersons belonged to a different union. Each such union had its own collective bargaining agreement, complete with a termination date different from that of every other union at the work site. The Wobblies called this typical arrangement “the American Separation of Labor.” The Preamble suggested a solution: These conditions can be changed and the interest of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its workers in any one industry, or all industries if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one the injury of all. The answer, in short, appeared to be the reorganization of labor in industrial rather than craft unions. It seemed to Wobblies and like-minded rank-and-file workers that if only labor were to organize industrially, the “separation of labor” — as the IWW characterized the old AF of L — could be overcome. All kinds of workers in a given workplace would belong to the same union and could take direct action together, as they chose. Hence in the early 1930s Wobblies and former Wobblies threw themselves into the organization of local industrial unions. A cruel disappointment awaited them. When John L. Lewis, Philip Murray, and other men of power in the new CIO negotiated the first contracts for auto workers and steelworkers, these contracts, even if only a few pages long, typically contained a no-strike clause. All workers in a given workplace were now prohibited from striking as particular crafts had been before. This remains the situation today. Nothing in labor law required a no-strike clause. Indeed, the drafters of the original National Labor Relations Act (or Wagner Act) went out of their way to ensure that the law would not be used to curtail the right to strike. Not only does federal labor law affirm the right “to engage in … concerted activities for the purpose of … mutual aid or protection”; even as amended by the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, Section 502 of what is now called the Labor Management Relations Act declares: Nothing in this Act shall be construed to require an individual employee to render labor or service without his consent, nor shall anything in this Act be construed to make the quitting of his labor by an individual employee an illegal act; nor shall any court issue any process to compel the performance by an individual employee of such labor or service, without his consent; nor shall the quitting of work by an employee or employees in good faith because of abnormally dangerous conditions for work at the place of employment of such employee or employees be deemed a strike under this chapter[;] and for good measure, the drafters added in Section 13 of the NLRA, now section 163 of the LMRA: “Nothing in this Act, except as specifically provided for herein, shall be construed so as either to interfere with or impede or diminish in any way the right to strike ….” In the face of this obvious concern on the part of the legislative drafters to protect the right to strike, the leaders of the emergent CIO gave that right away. To be sure, the courts helped, holding before World War II that workers who strike over economic issues can be replaced, and holding after World War II that a contract which provides for arbitration of grievances implicitly forbids strikes. But the courts are not responsible for the no-strike clause in the typical CIO contract. Trade union leaders are responsible. Charles Morris’ new book, The Blue Eagle at Work, argues that the original intent of federal labor law was that employers should be legally required to bargain, not only with unions that win NLRB elections, but also with so-called “minority” or “members-only” unions: unions that do not yet have majority support in a particular bargaining unit. We can all agree with Professor Morris that the best way to build a union is not by circulating authorization cards, but by winning small victories on the shop floor and engaging the company “in interim negotiations regarding workplace problems as they arise.” But Morris’ ultimate objective, like that of most labor historians and almost all union organizers, is still a union that negotiates a legally-enforcible collective bargaining agreement, including a management prerogatives clause that lets the boss close the plant and a no-strike clause that prevents the workers from doing anything about it In my view, and I believe in yours, nothing essential will change — not if Sweeney is replaced by Stern or Wilhelm, not if the SEIU breaks away from the AFL-CIO, not if the percentage of dues money devoted to organizing is multiplied many times — so long as working people are contractually prohibited from taking direct action whenever and however they may choose. Glaberman, Sargent, Mann, Barbero and Weir All this began to become clear to me only in the late 1960s, when a friend put in my hands a little booklet by Marty Glaberman entitled “Punching Out.” Therein Marty argues that in a workplace where there is a union and a collective bargaining contract, and the contract (as it almost always does) contains a no-strike clause, the shop steward becomes a cop for the boss. The worker is forbidden to help his buddy in time of need. An injury to one is no longer an injury to all. As I say these words of Marty Glaberman’s, almost forty years later, in my imagination he and the other departed comrades form up around me. We cannot see them but we can hear their words. John Sargent: “Without a contract we secured for ourselves agreement on working conditions and wages that we do not have today…. [A]s a result of the enthusiasm of the people in the mill you had a series of strikes, wildcats, shut-downs, slow-downs, anything working people could think of to secure for themselves what they decided they had to have.” Ed Mann: “I think we’ve got too much contract. You hate to be the guy who talks about the good old days, but I think the IWW had a darn good idea when they said: ‘Well, we’ll settle these things as they arise’.” Stan Weir: “[T]he new CIO leaders fought all attempts to build new industrial unions on a horizontal rather than the old vertical model…. There can be unions run by regular working people on the job. There have to be.” Rumbles In Olympus Here we should pause to take note of recent rumbles — in both senses of the word — on Mount Olympus. What is about to happen in the mainstream organized labor movement, and what do we think about it? This is a challenging question. Our energies are consumed by very small, very local organizing projects. It is natural to look sidewise at the organized labor movement, with its membership in the hundreds of thousands, its impressive national headquarters buildings, its apparently endless income from the dues check-off, its perpetual projects for turning the corner in organizing this year or next year, and to wonder, Are we wasting our time? Moreover, there is not and should not be an impenetrable wall between what we try to do and traditional trade unionism at the local level. My rule of thumb is that national unions and national union reform movements almost always do more harm than good, but that local unions are a different story. Workers need local unions. They will go on creating them whatever you and I may think, and for good reason. The critical decision for workers elected to local union office is whether they will use that position merely as a stepping stone to regional and national election campaigns, striving to rise vertically within the hierarchy of a particular union, or whether they will reach out horizontally to other workers and local union officers in other workplaces and other unions, so as to form class wide entities — parallel central labor bodies, or sometimes, even official central labor bodies — within particular localities. Such bodies have special historical importance. The “soviets” in the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 were improvised central labor bodies. Both the Knights of Labor and the IWW created such entities, especially during the first period of organizing in a given community when no single union was yet self-sufficient. My wife and I encountered a body of exactly this kind in Hebron in the occupied West Bank, and the Workers’ Solidarity Club of Youngstown was an effort in the same direction. The “workers’ centers” that seem to spring up naturally in communities of immigrant workers are another variant. What all these efforts have in common is that workers from different places of work sit in the same circle, and in the most natural way imaginable tend to transcend the parochialism of any particular union and to form a class point of view. Because many Wobblies will in this way become “dual carders,” and often vigorously take part in the affairs of local unions, the line between our work and the activity of traditional, centralized, national trade unions needs to be drawn all the more clearly. From my point of view, it is a case of Robert Frost’s two roads diverging within a wood: on the one hand, to mix metaphors, toward endless rearranging of the deck chairs on a sinking Titanic; on the other hand, toward the beginnings of another world. As you know I am an historian. And what drives me almost to tears is the spectacle of generation after generation of radicals seeking to change the world by cozying up to popular union leaders. Communists did it in the 1930s, as Len DeCaux became the CIO’s public relations man and Lee Pressman its general counsel; and Earl Browder, in an incident related by historian Nelson Lichtenstein, ordered Party members helping to lead the occupation of a General Motors plant near Detroit to give up their agitation lest they offend the CIO leadership. Trotskyists and ex-Trotskyists in the second half of the last century repeated this mistaken strategy of the Communist Party in the 1930s with less excuse, providing intellectual services for the campaigns of Walter Reuther, Arnold Miller, Ed Sadlowski, and Ron Carey. And Left intellectuals almost without exception hailed the elevation of John Sweeney to the presidency of the AFL-CIO in 1995. Professors formed an organization of sycophantic academics, and encouraged their students to become organizers under the direction of national union staffers. In a parody of Mississippi “freedom summer,” “union summers” used the energy of young people but denied them any voice in decisions. In all these variations on a theme, students and intellectuals sought to make themselves useful to the labor movement by way of a relationship to national unions, rather than by seeking a helpful relationship with rank-and-file workers and members of local unions. In contrast, students at Harvard and elsewhere organized their own sit-ins to assist low-wage workers at the schools where they studied, and then it was John Sweeney who showed up to offer support to efforts that, to the best of my knowledge, young people themselves controlled. I want to say a few more words about two exemplars of the paradigm I criticize: almost a century ago, John L. Lewis; and today, the not so dynamic duo, John Sweeney and Andrew Stern. Lewis is an historical conundrum. In the 1920s and early 1930s, he established dictatorial control over the United Mine Workers union and smashed individuals who sought to challenge him from below, like John Brophy and Powers Hapgood, and dissenting organizations like the Progressive Miners here in Illinois. However, to read his biographers from Saul Alinsky to Melvyn Dubofsky, like Paul on the road to Damascus the miners’ leader experienced conversion in 1932–1933. He seized on section 7(a) of the National Industrial Recovery Act and sent his organizers throughout the coal fields with the message, “The President wants you to join the union.” Then, confronting the standpat leadership of the AF of L, Lewis and other visionary leaders like Sidney Hillman led their members out of the AF of L to form, first the Committee for Industrial Organization, and then, after definitively seceding, the Congress of Industrial Organizations. James Pope of Rutgers University Law School has been into the sources and tells a different story. It was not Lewis, but rank-and-file miners in western Pennsylvania, who before the passage of the NIRA in spring 1933 began to form new local unions of the UMW. Lewis and his staff opposed them. Moreover, when in the summer and fall of 1933 the miners went on strike for union recognition, Lewis and his colleague Philip Murray repeatedly sought to settle strikes over the head of the workers on the picket lines although the goal of these massive direct actions had not been achieved. Yes, Lewis wanted more members, just as the leaders of the five rebelling unions today wish to increase union “density.” But what characterizes the national union leaders of the past and of the present is an absolute unwillingness to let rank-and-file workers decide for themselves when to undertake the sacrifice that direct action requires. Consider John Sweeney. Close observers should have known in the fall of 1995 that Sweeney was hardly the democrat some supposed him to be. Andrea Carney, who is with us today, was at the time a hospital worker and member of Local 399, SEIU in Los Angeles. She tells in The New Rank and File how the Central American custodians whom the SEIU celebrated in its “Justice for Janitors” campaign, joined Local 399 and then decided that they would like to have a voice in running it. They connected with Anglo workers like Ms. Carney to form a Multiracial Alliance that contested all offices on the local union executive board. In June 1995 they voted the entire board out of office. In September 1995, as one of his last acts before moving on to the AFL-CIO, Brother Sweeney removed all the newly-elected officers and put the local in trusteeship. This action did not deter the draftsmen of the open letter to Sweeney I mentioned earlier. Appearing at the end of 1995 in publications like In These Times and the New York Review of Books, the letter stated that Sweeney’s elevation was “the most heartening development in our nation’s political life since the heyday of the civil rights movement.” The letter continued: [T]e wave of hope that and energy that has begun to surge through the AFL-CIO offers a way out of our stalemate and defeatism. The commitment demonstrated by newly elected president John J. Sweeney and his energetic associates promises to once again make the house of labor a social movement around which we can rally. The letter concluded: “We extend our support and cooperation to this new leadership and pledge our solidarity with those in the AFL-CIO dedicated to the cause of union democracy and the remobilization of a dynamic new labor movement.” Signers included Stanley Aronowitz, Derrick Bell, Barbara Ehrenreich, Eric Foner, Todd Gitlin, David Montgomery, and Cornel West. Closely following Sweeney’s accession to the AFL-CIO presidency were his betrayals of strikes by Staley workers in Decatur, Illinois, and newspaper workers in Detroit. In Decatur, workers organized a spectacular “in plant” campaign of working to rule, and after Staley locked them out, there were the makings of a parallel central labor body and a local general strike including automobile and rubber workers. Striker and hunger striker Dan Lane spoke to the convention that elected Sweeney, and Sweeney personally promised Lane support if he would give up his hunger strike. But Sweeney did nothing to further the campaign to cause major consumers of Staley product to boycott the company. Meantime the Staley local had been persuaded to affiliate with the national Paperworkers’ union, which proceeded to organize acceptance of a concessionary contract. In Detroit – as Larry who is here could describe in more detail — strikers begged the new AFL-CIO leadership to convene a national solidarity rally in their support. Sweeney said No. On the occasion of Clinton’s second inauguration in January 1997, leaders of the striking unions — including Ron Carey — decided to call off the strike without consulting the men and women who had been walking the picket lines for a year and a half. Only then did the Sweeney leadership call on workers from all over the country to join in a, now meaningless, gathering in Detroit. What should the several dozen signers of the open letter to Sweeney have learned from these events? SEIU president Andrew Stern apparently believes that the lesson is that the union movement should be more centralized. What kind of labor movement would there be if he had his way? Local 399 had a membership of 25,000 spread all over metropolitan Los Angeles. The SEIU local where I live includes the states of Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia. This is topdown unionism run amok. The lesson for us is that, however humbly, in first steps however small, we need to be building a movement that is qualitatively different. The Zapatistas and the Bolivians: To Lead by Obeying And so of course we come in the end to the question, Yes, but how do we do that? Another world may be possible, but how do we get there? The Preamble says: “By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.” But if capitalist factories and mainstream trade unions are not prototypes of the new society, where is it being built? What can we do so that others and we ourselves do not just think and say that “another world is possible,” but actually begin to experience it, to live it, to taste it, here and now, within the shell of the old? In recent years I have glimpsed for the first time a possible answer: what Quakers call “way opening.” It begins with the Zapatistas, and has been further developed by the folks in the streets of Bolivia. Suppose the creation of a new society by the bourgeoisie is expressed in the equation, Rising Class plus New Institutions Within The Shell Of The Old = State Power. All these years I have been struggling with how workers could create new institutions within the shell of capitalism. What the Zapatistas have suggested, echoing an old Wobbly theme, is that the equation does not need to include the term “State Power.” Perhaps we can change capitalism fundamentally without taking state power. Perhaps we can change capitalism from below. All of us sense that something qualitatively different happened in Chiapas on January 1, 1994, something organically connected to the anti-globalization protests that began five years later. What exactly was that something? My wife Alice and I were in San Cristóbal a few years ago and had the opportunity to talk to a woman named Teresa Ortiz. She had lived in the area a long time and since then has published a book of oral histories of Chiapan women. Ms. Ortiz told us that there were three sources of Zapatismo. The first was the craving for land, the heritage of Emiliano Zapata and the revolution that he led at the time of World War I. This longing for economic independence expressed itself in the formation of communal landholdings, or ejidos, and the massive migration of impoverished campesinos into the Lacandón jungle. A second source of Zapatismo, we were told, was liberation theology. Bishop Samuel Ruiz was the key figure. He sponsored what came to be called tomar conciencia. It means “taking conscience,” just as we speak of “taking thought.” The process of taking conscience involved the creation of complex combinations of Mayan and Christian religiosity, as in the church Alice and I visited where there was no altar, where a thick bed of pine needles was strewn on the floor and little family groups sat in little circles with lighted candles, and where there was a saint to whom one could turn if the other saints did not do what they were asked. Taking conscience also resulted in countless grassroots functionaries with titles like “predeacon,” “deacon,” “catechist,” or “delegate of the Word”: the shop stewards of the people’s Church who have been indispensable everywhere in Latin America. The final and most intriguing component of Zapatismo, according to Teresa Ortiz, was the Mayan tradition of mandar obediciendo: “to lead by obeying.” She explained what it meant at the village level. Imagine all of us here as a village. We feel the need for, to use her examples, a teacher and a storekeeper. But these two persons can be freed for those communal tasks only if we, as a community, undertake to cultivate their milpas, their corn fields. In the most literal sense their ability to take leadership roles depends on our willingness to provide their livelihoods. When representatives thus chosen are asked to take part in regional gatherings, they are likely to be instructed delegates. Thus, during the initial negotiations in 1994, the Zapatista delegates insisted that the process be suspended for several weeks while they took what had been tentatively agreed to back to the villages, who rejected it. The heart of the process remains the gathered villagers, the local asemblea. Only upon reading a good deal of the Zapatista literature did an additional level of meaning become clear to me. At the time of the initial uprising, the Zapatistas seem to have entertained a traditional Marxist strategy of seizing national power by military means. The “First Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle,” issued on January 2, 1994, gave the Zapatista military forces the order: “Advance to the capital of the country, overcoming the federal army ….”[1] But, in the words of Harvard historian John Womack: “In military terms the EZLN offensive was a wonderful success on the first day, a pitiful calamity on the second.”[2] Within a very short time, three things apparently happened: 1) the public opinion of Mexican civil society came down on the side of the Indians of Chiapas and demanded negotiation; 2) President Salinas declared a ceasefire, and sent an emissary to negotiate in the cathedral of San Cristóbal; 3) Subcomandante Marcos carried out a clandestine coup within the failed revolution, agreed to negotiations, and began to promulgate a dramatically new strategy.[3] Beginning early in 1994, Marcos says explicitly, over and over and over again: We don’t see ourselves as a vanguard and we don’t want to take state power. Thus, at the first massive encuentro, the National Democratic Convention in the Lacandón jungle in August 1994, Marcos said that the Zapatistas had made “a decision not to impose our point of view”; that they rejected “the doubtful honor of being the historical vanguard of the multiple vanguards that plague us”; and finally: Yes, the moment has come to say to everyone that we neither want, nor are we able, to occupy the place that some hope we will occupy, the place from which all opinions will come, all the answers, all the routes, all the truth. We are not going to do that.[4] Marcos then took the Mexican flag and gave it to the delegates, in effect telling them: “It’s your flag. Use it to make a democratic Mexico. We Zapatistas hope we have created some space within which you can act.” [5] What? A Left group that doesn’t want state power? There must be some mistake. But no, he means it. And because it is a perspective so different from that traditional in Marxism, because it represents a fresh synthesis of what is best in the Marxist and anarchist traditions, I want to quote several more examples.[6] In the “Fourth Declaration from the Lacandón Jungle,” on January 1, 1996, it is stated that the Zapatista Front of National Liberation will be a “political force that does not aspire to take power[,] … that can organize citizens’ demands and proposals so that he who commands, commands in obedience to the popular will[,] … that does not struggle to take political power but for the democracy where those who command, command by obeying.” In September 1996, in an address to Mexican civil society, Marcos says that in responding to the earthquake of 1985 Mexican civil society proved to itself that you can participate without aspiring to public office, that you can organize politically without being in a political party, that you can keep an eye on the government and pressure it to “lead by obeying,” that you can have an effect and remain yourself ….[7] Likewise in August 1997, in “Discussion Documents for the Founding Congress of the Zapatista Front of National Liberation,” the Zapatistas declare that they represent “a new form of doing politics, without aspiring to take power and without vanguardist positions.” We “will not struggle to take power,” they continue. The Zapatista Front of National Liberation “does not aspire to take power.” Rather, “we are a political force that does not seek to take power, that does not pretend to be the vanguard of a specific class, or of society as a whole.”[8] Especially memorable is a communication from the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) dated October 2, 1998 and addressed to “the Generation of Dignity of 1968,” that is, to former students who had survived the massacre in Mexico City prior to the 1968 Olympics. Here Marcos speaks of “the politics of below,” of the “Mexico of those who weren’t then, are not now, and will never be leaders.” This, he says, is the Mexico of those who don’t build ladders to climb above others, but who look beside them to find another and make him or her their compañero or compañera, brother, sister, mate, buddy, friend, colleague, or whatever word is used to describe that long, treacherous, collective path that is the struggle of: everything for everyone.[9] Finally, at the zocalo in March 2001, after this Coxey’s Army of the poor had marched from Chiapas to Mexico City, Marcos once more declared: “We are not those who aspire to take power and then impose the way and the word. We will not be.”[10] For the last four years the Zapatistas and Marcos have been quiet, presumably building the new society day by day in those villages of Chiapas where they have majority support. If one wishes further insight as to how the politics of below might unfold, the place to look may be Bolivia. It’s too soon to say a great deal. The most substantial analysis I have encountered describes the movement in the language of “leading by obeying”: without seizing power directly, popular movements … suddenly exercised substantial, ongoing control from below of state authorities …. and: the … insurrectionists did not attempt to seize the state administration, and instead set up alternative institutions of self-government in city streets and neighborhoods … and in the insurgent highlands …. Protesters, who took over the downtown center, intentionally refrained from marching on the national palace. This was to avoid bloodshed, but also a recognition that substantial power was already in their hands. International Solidarity.[11] There remains, finally, the most difficult problem of all. “An injury to one is an injury to all” means that we must act in solidarity with working people everywhere, so that, in the words of the Preamble, “the workers of the world organize as a class.” This means that we cannot join with steel industry executives in seeking to keep foreign steel out of the country: we need a solution to worldwide over-capacity that protects steelworkers everywhere. We cannot, like the so-called reform candidate for president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters a few years ago, advocate even more effort to keep Mexican truck drivers from crossing the Rio Grande. We should emulate the Teamsters local in Chicago where a resolution against the Iraq war passed overwhelmingly after Vietnam vets took the mike to share their experience, and the local went on to host the founding national meeting of Labor Against The War. I believe the IWW has a special contribution to make. Wobblies were alone or almost alone among labor organizations a hundred years ago to welcome as members African Americans, unskilled foreign-born workers, and women. Joe Hill not only was born in Sweden and apparently took part in the Mexican Revolution, but, according to Franklin Rosemont, may have had a special fondness for Chinese cooking. This culture of internationalism can sustain and inspire us as we seek concrete ways to express it in the 21st century. I have concluded that no imaginable labor movement or people’s movement in this country will ever be sufficiently strong that it, alone, can confront and transform United States capitalism and imperialism. I am not the only person who has reached this conclusion, but most who do so then say to themselves, I believe, “OK, then I need to cease pretending to be a revolutionary and support reform instead.” I suggest that what we need is an alternative revolutionary strategy. That strategy, it seems to me, can only be an alliance between whatever movement can be brought into being in the United States and the vast, tumultuous resistance of the developing world. Note that I say “alliance,” as between students and workers, or any other equal partners. I am not talking about kneejerk, uncritical support for the most recent Third World autocrat to capture our imaginations. We in Youngstown have taken some very small first steps in this direction that I would like to share. In the late 1980s skilled workers from Youngstown, Aliquippa, and Pittsburgh made a trip to Nicaragua. Ned Mann, Ed Mann’s son, is a sheet metal worker. He helped steelworkers at Nicaragua’s only steel mill, at Tipitapa north of Managua, to build a vent in the roof over a particularly smoky furnace. Meantime the late Bob Schindler, a lineman for Ohio Edison, worked with a crew of Nicaraguans doing similar work. He spoke no Spanish, they spoke no English. They got on fine. Bob was horrified at the tools available to his colleagues and, when he got back to the States, collected a good deal of Ohio Edison’s inventory and sent it South. The next year, he went back to Nicaragua, and travelled to the northern village where Benjamin Linder was killed while trying to develop a small hydro-electric project. Bob did what he could to complete Linder’s dream. About a dozen of us from Youngstown have also gone to a labor school south of Mexico City related to the Frente Autentico del Trabajo, the network of unions independent of the Mexican government. These are tiny first steps, I know. But they are in the right direction. Why not take learning Spanish more seriously and, whenever we can, encourage fellow workers to join us in spending time with our Latin American counterparts? And on down that same road, why not, some day, joint strike demands from workers for General Motors in Puebla, Mexico; in Detroit; and in St. Catherine’s, Ontario? Instead of the TDU candidate for president of the Teamsters criticizing Jimmy Hoffa for doing too little to keep Mexican truck drivers out of the United States, why not a conference of truck drivers north and south of the Rio Grande to draw up a single set of demands? Why not, instead of the United Steelworkers joining with US steel companies to lobby for increased quotas on steel imports, a task force of steelworkers from all countries to draw up a common program about how to deal with capitalist over-production, how to make sure that each major developing country controls its own steelmaking capacity, and how to protect the livelihoods of all steelworkers, wherever they may live? Perhaps I can end, as I began, with a story. About a dozen years ago my wife and I were in the Golan Heights, a part of Syria occupied by Israel in 1967. There are a few Arab villages left in the Golan Heights, and at one of them our group was invited to a barbecue in an apple orchard. There was a very formidable white lightning, called arak. It developed that each group was called on to sing for the other. I was nominated for our group. I decided to sing “Joe Hill” but I felt that, before doing so, I needed to make it clear that Joe Hill was not a typical parochial American. As I laboriously began to do so, our host, who had had more to drink than I, held up his hand. “You don’t have to explain. We understand. Joe Hill was a Spartacist. Joe Hill was in Chile and in Mexico. But today,” he finished, “Joe Hill is a Palestinian.” Joe Hill is a Palestinian. He is also an Israeli refusenik. He is imprisoned in Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo, where his Koran along with the rest of his belongings is subject to constant shakedowns and disrespect. He works for Walmart and also in South African diamond mines. He took part in the worldwide dock strike a few years ago and sees in that kind of international solidarity the hope of the future. Recently he has spent a lot of time in occupied factories in Argentina, where he shuttles back and forth between the workers in the plants and the neighborhoods that support them. In New York City, Joe Hill has taken note of the fact that a business like a grocery store (in working-class neighborhoods) or restaurants (in midtown Manhattan) are vulnerable to consumer boycotts, and if the pickets present themselves as a community group there is no violation of labor law. In Pennsylvania, he has the cell next to Mumia Abu Jamal at S.C.I. Greene in Waynesburg. In Ohio, he hangs out with the “Lucasville Five”: the five men framed and condemned to death because they were leaders in a 1993 prison uprising. He was in Seattle, Quebec City, Genoa, and Cancun, and will be at the next demonstration against globalization wherever it takes place. In Bolivia he wears a black hat and is in the streets, protesting the privatization of water and natural gas, calling for the nationalization of these resources, and for government from below by a people’s assembly. As the song says, “Where workingmen are out on strike, it’s there you’ll find Joe Hill.” Let’s do our best to be there beside him. [1] Our word is our weapon: selected writings [of] subcomandante Marcos , ed. Juane Ponce de León (Seven Stories Press: New York, 2001), p. 14. [2] John Womack, Jr., Rebellion in Chiapas: An Historical Reader (New York: The New Press, 1999), p. 43. [3] Id. , p. 44. [4] Shadows of Tender Fury: The Letters and Communiques of Subcomandante Marcos and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation , trans. by Frank Bardacke and others (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1995), p. 248. [5] Id. , pp. 249–51. [6] Rebellion in Chiapas , pp. 302–02. [7] “Civil Society That So Perturbs,” Sept. 19, 1996, Our word is our weapon, p. 121 (emphasis added). [8] Rebellion in Chiapas , pp. 333, 335–36. [9] Our word is our weapon , pp. 144–45. [10] Id. , p. 159. [11] Forrest Hylton and Sinclair Thomson, “Revolutionary Horizons: Indigenous and National-Popular Struggles in Bolivia,” New Left Review (forthcoming), pp. 7, 35. Workers’ Democracy (2002) Conventional definitions of union democracy are too limited to encompass the broad majority of people in and outside unions who are struggling for control over their workplaces. In particular, denotation of U.S. labor law and trade union perspectives of union democracy are far too narrow to give workers participatory power. Thus the concept of union democracy must be reinterpreted to include workers of all kinds (unionized workers, nonunion workers, and farmers); protection of the rights to strike, picket, and slow down; and the demand for worker-community ownership. This article examines two recent examples of workers’ democracy: the Serbian revolution of 2000 and the Zapatistas’ ongoing struggle in Chiapas, Mexico. What kind of democracy do workers need? Those who answer, “Union democracy,” generally mean by that term the free exercise of rights protected by Title I of the Landrum-Griffin Act, together with the right to elect union officers and ratify contracts by referendum vote of the rank and file. (A referendum vote is protected by Title I only if provided in the constitution and bylaws of the union to which the complaining worker belongs.) “Union democracy,” thus defined, is critically important for the one worker in eight who belongs to a union. The right to speak your piece at a meeting, to belong to a caucus without retaliation, to circulate leaflets and petitions, and to run for office represent labor law equivalents to many of the rights protected by the First Amendment. Even for the worker who belongs to a union, however, union democracy understood in First Amendment terms does not encompass all the democracy that a worker needs. Labor law in the United States as expressed in the National Labor Relations Act as amended (otherwise known as the Labor Management Relations Act) has a number of features that are found in few other countries and that are a threat to democratic values. In the United States, federal labor law as interpreted by the National Labor Relations Board and the courts provides that: