|

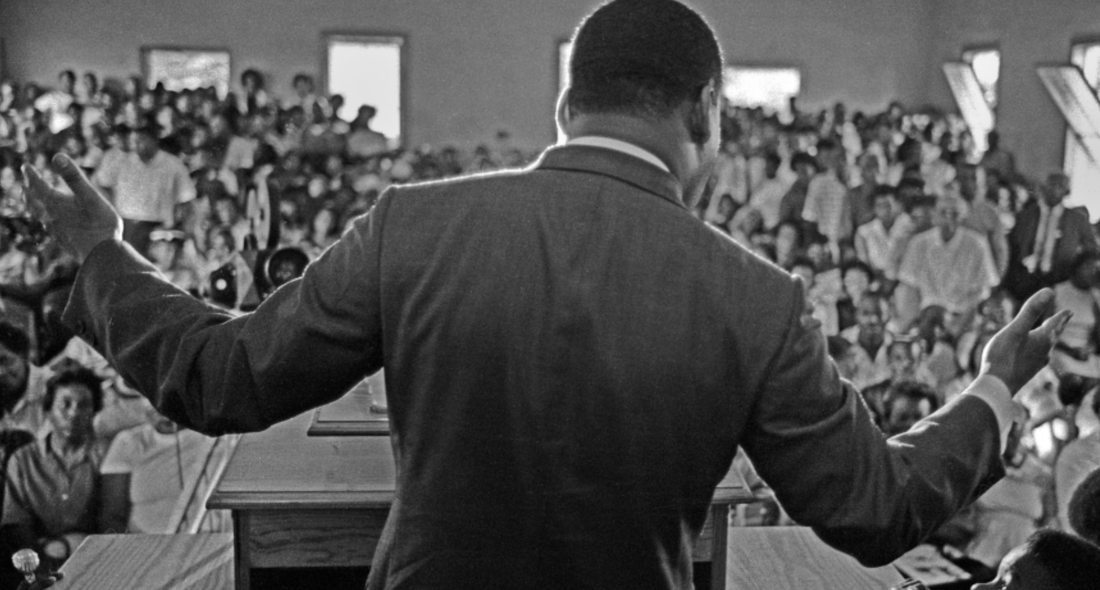

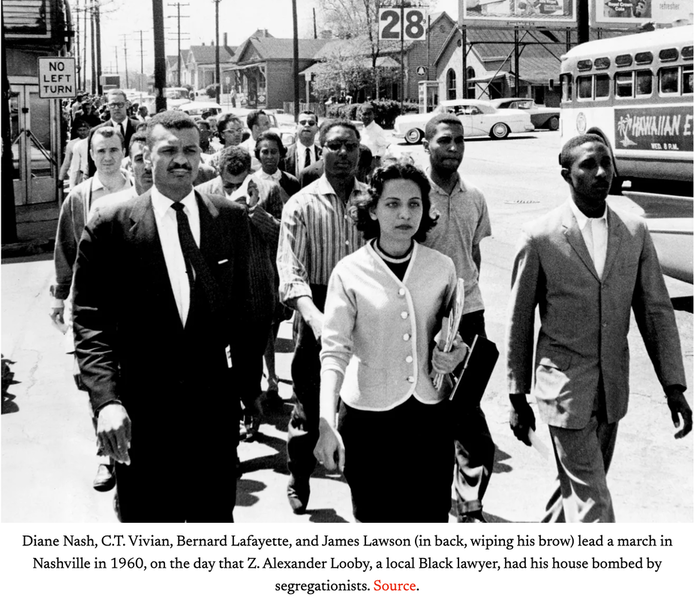

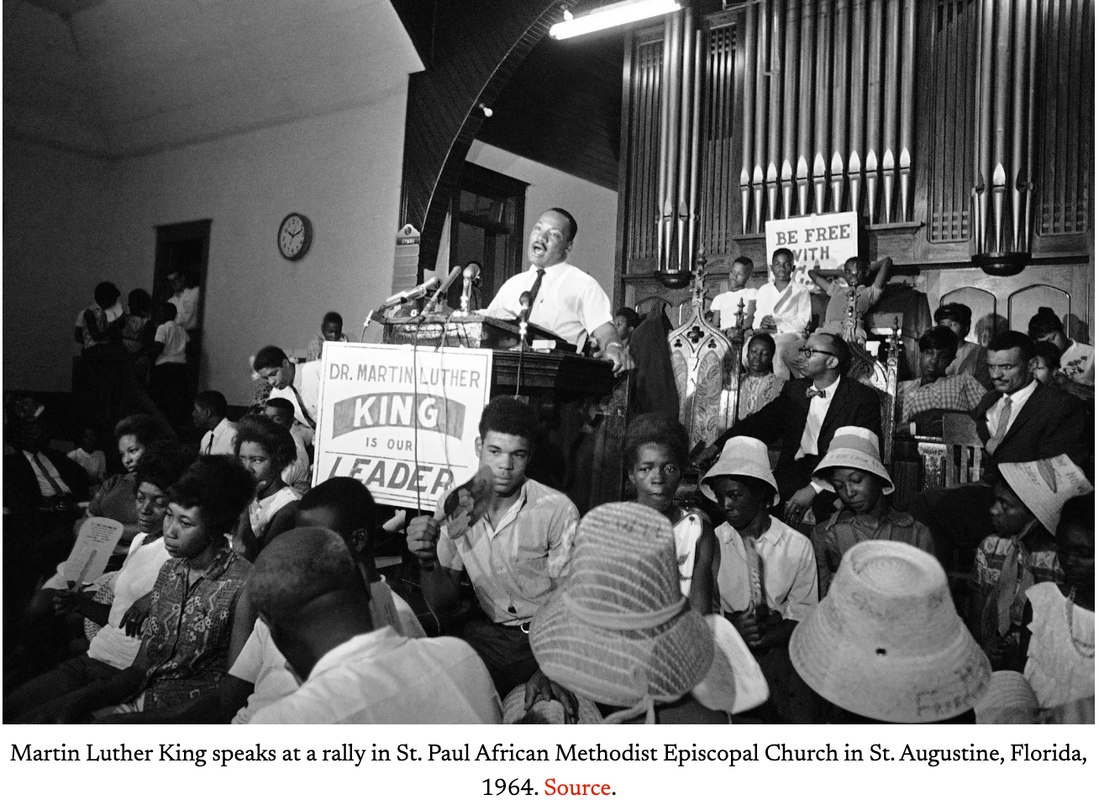

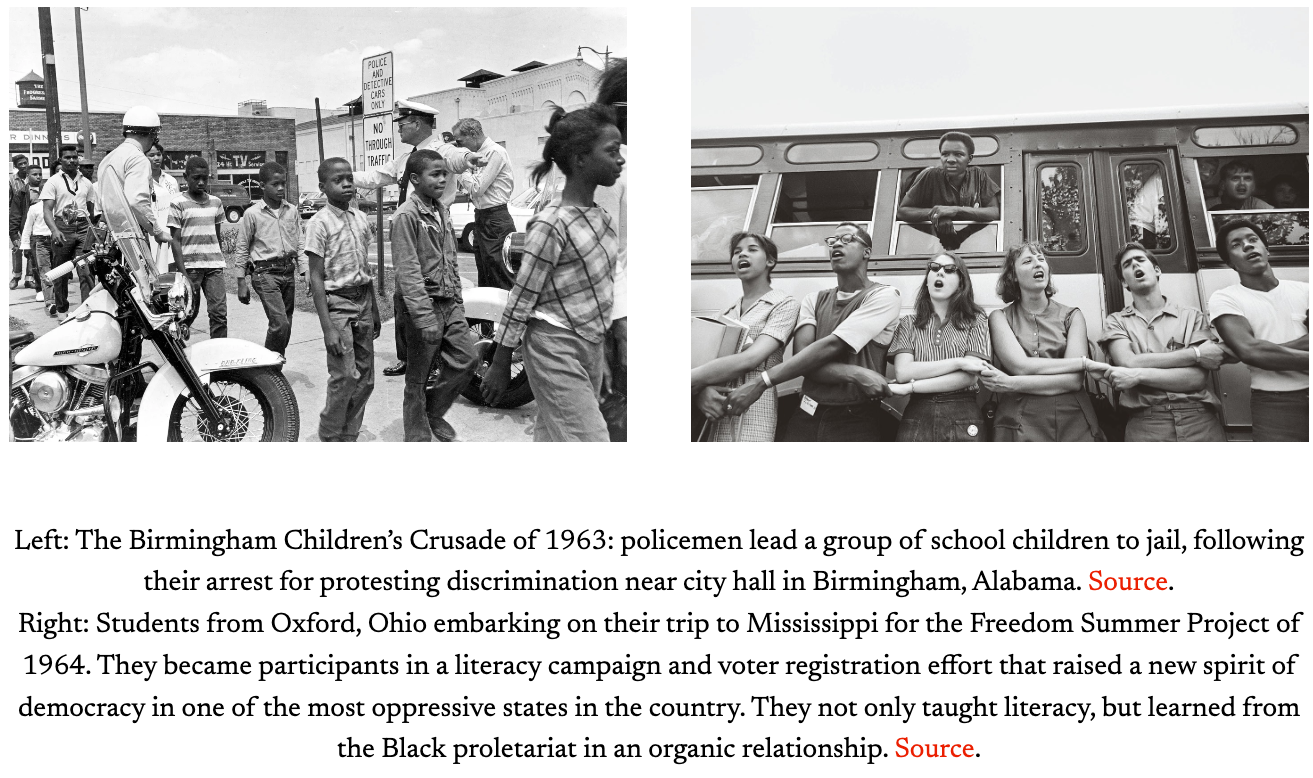

On what basis do we call the Civil Rights Movement a revolution? And will there be one to follow? The year is 2024. America is today engulfed in its greatest political crisis perhaps since the Civil War. The blatant hypocrisy and contempt shown by our elites, decades of deindustrialization, neglect, and downward economic mobility, cities and towns overrun by deaths of despair, and America’s most recent proxy wars in Gaza and Ukraine have, in unprecedented fashion, driven Americans away from the current political establishment and toward the memory of that last great movement led by Martin Luther King and a sea of people who called themselves freedom fighters. This was the Third American Revolution, and we are its children. It rests in our hands to determine whether there will be a Fourth. To speak, then, of this history is not to regress into some dead past—it is to enter into battle for our present and future. Now is the time to face our inheritance. Prologue: The Revolutionary Diane Nash was 21 years old when she, along with a small number of other students from various Black colleges in Nashville, began attending James Lawson’s workshops on nonviolence in 1959. Raised in Chicago, Nash had not encountered the full harshness and humiliating irrationality of segregation until she came to the South; Lawson’s workshops, inspired by his studies in India, were the “only game in town” where anyone talked about ending segregation. Over the course of many months, the group met, discussed, and debated—oftentimes for hours—over a series of formidable questions: was nonviolence a viable philosophy and method? Could nonviolent change ever take place in the hyper-violent American South? What would it take to desegregate Nashville? Who and what were the social forces, individuals, and institutions that mattered in the city, and how did they think and behave? Where should the effort to desegregate Nashville begin, and why? And finally: could each student accept the possibility of his or her death at the hands of an enraged white mob? Aimed at desegregating lunch counters and other public facilities, the Nashville Sit-Ins of 1960 were the product of these months of exhaustive investigation, deliberation, and planning. It was one of the nation’s earliest, most audacious nonviolent direct action campaigns, and a microcosm for how the Civil Rights Movement created new human beings and new human relations: a condition for the rebirth of America as a nation and as a civilization in potentiality. Initially shy and timid, Nash grew to become the unquestioned leader among this cadre of students and a respected, battle-tested revolutionary in the Civil Rights Movement. What produced a Diane Nash? To answer this question, we must rewrite our entire understanding of American history and of the very question of revolution. An American Canon For the current generation of activists, leftists, and young people, it does not normally occur to us to think of the Civil Rights Movement as a revolution, nor of America having a revolutionary tradition beyond perhaps 1776. Our chronology of modern revolutionary history usually begins in 1917; our ideological references are Marx and Lenin. There is a great irony in this: Martin Luther King and the Black Freedom Movement are more foreign to us than the Russian Revolution. We cannot comprehend a revolution that used Nonviolence and Love as its theoretical framework, just as seriously as the Bolsheviks used Marxism. So we dismiss the Civil Rights Movement as a bourgeois reform effort or quaint morality play; we cast figures like King as naive, or “problematic,” or insufficiently radical because they do not fit some imagined criteria of what it means to be a revolutionary. It is this assumption, this blind spot, which is our worst enemy; by it, we cripple our revolutionary potential, place ourselves in opposition to our own people, and give aid and comfort to the ruling class. We assemble fantasies of revolution and miss the glaring truth: revolutions are made by human beings. Any attempt at constructing a revolutionary vision in the United States must ultimately be anchored by the human qualities—and devoted to awakening the human capacity—of the people who make up this nation. Defining the Third American Revolution as such requires a rethinking of revolutionary chronology and science. This does not mean discarding the experience of the Russian Revolution. But recognizing a Third American Revolution means locating a different point of origin for ourselves within the revolutionary history of the United States. More concretely, it means starting with the Second American Revolution: the Civil War and Reconstruction, the epic battle to bring down the slave system. Given far less credence than the First, it addressed the central contradiction emanating from 1776—slavery—thereby bringing new life to the American democratic experiment and yielding far greater impact in the grand scheme of history. From the furnace of this Second American Revolution, three prophets were born whose words and deeds serve as the North Star of this nation’s revolutionary tradition: W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King Jr., and James Baldwin. Put together, their work forms an organic whole, a basic paradigm for American revolutionary thought. Du Bois, the greatest scholar of the 20th century, furnished the Black Freedom Movement with a method for understanding and intervening in the course of human action; King, the principal leader of the Third American Revolution, and Baldwin, who bore prophetic witness for this Revolution, both operated within the framework of Du Boisian science. It was no coincidence that King turned to Du Bois’s writing at the height of the Movement to make sense of the present revolution that was unfolding in America. Du Bois’s monumental Black Reconstruction in America identified the enslaved Africans in America as workers—a figure of modernity. He then argued that the central category of the American revolutionary process was the Black Worker. This was, first, a recognition of the central fact that the rise of capitalism in the U.S. and Western world depended on the Transatlantic Slave Trade and chattel slavery—an oppression of an ancient form that yet produced a new world system never before seen in human history. Thus the freeing of four million slaves, the toppling of the planter class, and the reconstruction of a new state in the American South all constituted a “revolution on a mighty scale and with world-wide reverberation”—one which helped make possible the October Revolution of 1917. Du Bois further saw that the condition of enslavement, disenfranchisement, and segregation produced, in the United States, a distinct social group with a highly unusual consciousness. Locked out of the pale of humanity by a white civilization, the enslaved were forced to grapple with and construct their own sense of humanity. Locked out of economic opportunities afforded to most immigrants, many slaves upon achieving freedom aspired to become not autonomous, self-made individuals but rather freedom fighters for their people still in bondage. They wanted freedom; they wanted education; they wanted an end to the plantation system; they wanted land to till; they wanted to work, but to be free workers; they wanted dignity. The proletariat, as formulated by Marx and Engels, refers not merely to an economic relation; the proletariat is a category of consciousness and social organization. Black folk were compelled, by necessity, to develop tightly knit social institutions to ensure group survival. Foremost among them was the Black church: a sanctuary for communion with the divine, a gathering place for social life, a vessel for historical memory, a training ground for organic leadership, a site of ideological struggle, and a vehicle for freedom and protest. It was here that a new kind of proletariat emerged through the dialectic of history. The Black proletariat defied the ideology of a white supremacist Christianity and inscribed their own struggle for freedom onto the Biblical narrative. Where the European working class saw itself in the propertyless proletariat of antiquity, Black folk saw themselves in the Exodus story of Moses and the Israelites fleeing Egypt, or in the early Christians, forced underground by the Roman Empire. It was the Black proletariat’s unique consciousness of social reality that decided the fate of the Civil War. The arrival of the Union army to the South meant, for the slaves, the fulfillment of divine prophecy. “To four million black folk emancipated by civil war,” Du Bois wrote, “God was real”—and His visage was Freedom. This sense of prophecy, this ability to see themselves as central actors in the dramatic unfolding of history, gave tens of thousands of slaves the courage to abandon the plantation, risking death, and join the Union forces. The withdrawal of their labor crippled the Confederacy and swung the war toward the Union, setting the stage for Reconstruction, the greatest experiment in a radical worker’s democracy the world had yet seen, as the masses of Black folk threw themselves into the difficult task of rebuilding a land ravaged by war. The subsequent counter-revolution against this experiment, enacted by a new alliance between rising industrial capital and white labor, decimated Black folk and set them to wander for a generation in the wilderness of America. For his study of this period, Du Bois used Marx but was not bound to classical Marxist standards. He did not ask the dogmatic question, Was Reconstruction a revolution or not? Instead he asked, What kind of revolution was this? What was the logic of its development? What does it reveal about America’s historical trajectory and revolutionary, democratic possibility? Above all, what did it mean to those four million Black slaves who, on a fateful night, made the leap toward freedom and thrust themselves onto the stage of world history? Here is where our understanding of the Third American Revolution must begin. It was part and parcel of world revolutionary processes in the 20th century; King, Lenin, Mao, and Gandhi alike ventured to resolve the same questions of democratic rule that had been raised by the modern epoch. And yet, the Black Freedom Movement of the 1950s-70s was a revolution of a different type—one whose full magnitude, quality, and depth have yet to be fully realized. It was distinct from other revolutions that were guided by Marx and Lenin; it laid a blueprint for future democratic revolutions seeking to address the contradictions of advanced capitalist societies. It is a vast goldmine beneath the feet of the American citizenry, waiting to be unearthed and used in the fire of a new struggle. The Black Freedom Movement: Making Time Real To the outside observer, it seems strange that a new revolutionary movement should have begun in the U.S. in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama. Conventional thought would tend to see greater revolutionary possibility in a period of intense economic crisis such as the 1930s, compared to a period of relative domestic economic prosperity like the 1950s. Flushed with victory and unscathed by the Second World War, America faced the latter half of the 20th century as an industrial superpower on the ascendancy. Internal dissent seemed to have been solved by McCarthyism. To the extent that America’s elites thought about the “Negro problem,” they assumed they could allow the worst excesses of segregation to gradually dissipate over time, without fundamentally changing the economic, political, or social structure of the country. The U.S. ruling class, seeing itself in nearly godlike terms as America subdued its mother Europe and much of the world to preserve the remnants of Western imperialism, believed it held the reins of history. It could not imagine a movement rising from the lowliest, most forsaken backwaters of the South to directly challenge its own authority. To the children and grandchildren of the former slaves, however, the outpouring of the nonviolent movement in Montgomery and soon a hundred other cities made all the sense in the world. What Black folk saw in the immediate postwar period was a world freedom movement flooding across humanity, as the system of colonial imperialism came under crisis. From Alabama to New York, from Tennessee to Florida, from Mississippi to Pennsylvania, over kitchen tables, among church pews, and in shaded street corners, news of the anti-colonial struggles of Africa and Asia spilled into the vision, hearing, speech, thoughts, and hearts of Black people. The remarkable victories of poorer, darker peoples over once-invincible Western empires forced Black folk in America to reflect on their own lack of freedom—in a nation that proclaimed its own “freedom” as a model for the world, no less. It was doubly fateful that the Black proletariat saw the 100th anniversary of Emancipation approaching; for it was the defeat of Reconstruction which had, as Du Bois explained, laid the foundation for the ascendance of U.S. and European imperialism at the sunset of the 19th century. From the nation’s halls of power, the Black proletariat heard the constant refrain: “Wait.” Yet from the turning of a world far vaster, the Black proletariat felt the thunderous cry: “Move.” So they moved. And through their movement, hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands of ordinary working people commandeered the pace and direction of social-historical time in the United States. Martin Luther King wrote of this phenomenon in Why We Can’t Wait: “Sarah Turner closed the kitchen cupboard and went into the streets; John Wilkins shut down the elevator and enlisted in the nonviolent army; Bill Griggs slammed the brakes of his truck and slid to the sidewalk; the Reverend Arthur Jones led his flock into the streets and held church in jail. The words and actions of parliaments and statesmen, of kings and prime ministers, movie stars and athletes, were shifted from the front pages to make room for the history-making deeds of the servants, the drivers, the elevator operators and the ministers.” For King, it was not only the bitter reality of oppression, but Black folk’s consciousness of their place in history that gave them the faith, urgency, and audacity to take time into their own hands. “The milestone of the centennial of emancipation,” he wrote, “gave the Negro a reason to act—a reason so simple and obvious that he almost had to step back to see it.” Nowhere was that consciousness reflected more clearly than in the Southern student movement helmed by a new generation of Black youth, for whom James Baldwin bore witness in 1960: “Americans keep wondering what has ‘got into’ the students. What has ‘got into’ them is their history in this country. They are not the first Negroes to face mobs: they are merely the first Negroes to frighten the mob more than the mob frightens them.… The question with which they present the nation is whether or not we really want to be free. It is because these students remain so closely related to their past that they are able to face with such authority a population ignorant of its history and enslaved by a myth.… These students prove unmistakably what most people in this country have yet to discover: that time is real.” Nonviolence and the Revolutionary Imperative The advent of nonviolence was the spark that made this breakthrough possible. Nonviolence has been so distorted in the pages of our history that it is necessary to completely abandon our prevailing notions of it and return to the source for a more useful interpretation of its meaning. First formulated by Mahatma Gandhi in the struggle against British imperialism and further developed by the Civil Rights Movement in America, nonviolence was not only a method of protest against injustice: nonviolence was a social process. We must remember that the Color Line constituted a basic condition of American social life. If capitalism socializes various functions and contradictions of human relations, then the Color Line embodied the most explicitly social problem for the American working class to face. In other words, racism presented a clear contradiction that the people themselves had to resolve. America’s white supremacist social system was designed to beat Black people down, to rob them of their dignity, to destroy their families and social ties, to keep them anxious in terror of the white mob, to undermine their consciousness of themselves, and to trap them perpetually within the lowest, most exploitative level of labor. For generations, the scourge of this system had worked day and night to break Black people’s will to struggle for a better future. On the other hand, it took thinkers like Du Bois and Baldwin to show just how much white supremacy also degraded and debased the ordinary white American. It rendered him utterly dependent upon a ruling class to give him his aspirations and sense of reality. It robbed him of his democratic instinct—of his ability to think for himself. It trapped him, helplessly, within a false identity: an identity held captive by a lie about the inferior humanity of another. The innovation of nonviolence for the American situation did two things from the start: it transformed the Black proletariat once more into a fighting people, and it shattered the false system of reality that imprisoned the white American. On this basis, the Third American Revolution set about forging a new social contract and democratic consciousness among the American people—in essence, began a process for the birth of a new American people. Nonviolence drew from the example set by the slaves during their exodus from the plantations in the heat of the Civil War—what Du Bois called the General Strike. Further synthesizing this Black tradition of mass noncooperation with Gandhi’s satyagraha, King and the Civil Rights Movement developed nonviolence into a powerful, highly disciplined method of political activity and social change. Seldom recognized for his philosophical and political genius, King became the leader of the Movement because he knew his people and he knew America. He sensed the precise moment when Black people were “ready for mass action, ready for its risks, and ready for its responsibilities.” He was an earthquake in the landscape of American religious and political orthodoxy, harnessing the Black church and prophetic tradition to their fullest power. He broke the McCarthyite consensus that had frozen the nation into ideological sterility. Through his words and by his willingness to suffer, he challenged Black and white people alike in a way that no figure ever had or has since. Like water in the desert, or light roaring down from heaven, nonviolence forged a path to democratizing America that has not yet been fully realized. This was the dialectic of the Movement: it forced American bourgeois democracy to fulfill its long-forsaken promise of legal equality and enfranchisement to Black folk, while at the same time conceiving a new type of democracy directly in the battles and campaigns waged across the South and North. The Civil Rights Movement comprised manifold phenomena at once. It was an odyssey of human discovery, sending waves of pioneers out among the most destitute, fearsome territories of the Jim Crow South to win over the people to a new vision of the future. It enlisted young and old, poor and professional, industrial and domestic worker, man and woman, southerner and northerner, believer and non-believer, Black and white into an army of equals—and instilled in them the confidence that they could decide the future of the country. It yielded a vast labor movement that in the end organized tens of thousands of unorganized Black workers in the South. It created a channel for Black and white people to relate to one another with unflinching openness and uncommon honesty—seeking to fulfill Du Bois’s vision of a “creative relationship” between white and Black workers. It produced a generation of leaders, artists, and intellectuals who were tested on the threshing floor of mass struggle. It compelled millions of white Americans to grapple, for the first time, with their own passivity and political immaturity, their own mediocre aspirations and moral standards. And drawing the beast of segregation out into the open for all humanity to see, it directly confronted the U.S. state at the local, state, federal, and international level, paralyzed the state’s normal functions, and bent it to the point of breaking. On the eve of the October Revolution, Lenin looked to the Soviet councils created by Russian workers and saw the seeds of a new democratic state that could supplant the crumbling Tsarist regime. In the whirlwind of the Third American Revolution, King saw the new human beings and social relations being created through nonviolent action and understood that therein lay the possibilities for a new people’s democracy in the United States. His name for it was the Beloved Community. Baldwin translated this vision into a task: “achieving our country.” The Human Heart: Where Civilization Begins Before embarking on their Sit-In campaign, the Nashville students trained relentlessly with each other to endure physical and verbal abuse—to kill the natural instinct within themselves to flee or fight back, and reach a new plane of human ability that stood unmoved by the gales of hatred, fear, indifference, intimidation, violence, and death. Their eventual collision with these forces took place, simultaneously, in dramatic confrontations in the public square and in the private reaches of the human soul. It was in this same vein that Baldwin wrote of King’s presence in Montgomery: “Martin Luther King, Jr., by the power of his personality and the force of his beliefs, has injected a new dimension into our ferocious struggle. He has succeeded, in a way no Negro before him has managed to do, to carry the battle into the individual heart and make its resolution the province of the individual will.” This battle of the human heart erupted in every single encounter between the apostles for freedom and their countrymen. Here, in so little as a brief moment of eye contact, the former could level a challenge to the latter: I am not who you think I am. Who, then, are you going to be? The Civil Rights Movement was the first true mass phenomenon to be experienced by the whole nation through the new technology of television. Raw footage of children being battered by fire hoses, mauled by police dogs, paraded to jail, and beaten by mobs filled the living rooms of tens of millions of American households. The country’s white majority was forced to recognize, first, that the Negro was not happy in his designated place as Southern authorities had proclaimed; and second, that all Americans were implicated in the moral storm that the Movement had brought to the surface of the nation’s conscience. The question of morality has long been distorted by liberals and dismissed by radicals. Yet in the eyes of King, Lawson, Nash, Baldwin, and many others in the Movement, morality was conceived as an essential task of democracy and civilization. The “moral choice,” as Baldwin framed it, meant that all Americans must confront themselves as products and agents of a complex, still-unfolding history; and, on those terms, face the question of whether they could take responsibility for their own lives and the life of their country—or, surrender their sovereignty to the hands of the butchers, liars, and fools who ruled the nation. When King called for a “revolution of values” at the height of the war in Vietnam, he was therefore calling upon the American people to assert that the basic tenets of civilization belonged to them, and not the ruling elite. Du Bois, King, and Baldwin all envisioned an America that could break free from the confines of a dying Western civilization—to become, simultaneously, truly American and a synthesis of the world’s civilizations, especially the rising Afro-Asiatic axis of world humanity. If civilization in America was to be reborn, then that future took root in the heart of one like Diane Nash, who was prepared to die for freedom. She and all the Movement’s young people, Black and white, who rushed toward the crucible of danger to wage the Sit-Ins, the Freedom Rides, the Children’s Crusade, and the Freedom Summer Project, forged a fierce bond among each other—and achieved a personal, moral authority through their sacrifice—that set a new standard for the rest of the nation to emulate. From Montgomery to Nashville to Birmingham, the soldiers of the nonviolent army unleashed a new human possibility in the estranged landscape of modern American society. They called it love—“the sword that heals.” The War That Came It is commonly said that King became “more radical” in his later years. This is a fundamental misreading: the Civil Rights Movement and its strongest adherents were revolutionary from the beginning. Revolutions do not happen overnight, but rather proceed in stages; even a sudden lightning strike of revolutionary action is the result of deeper processes of change, tension, and protracted struggle. With each victory and mark of progress, the Third American Revolution faced new questions, challenges, and contradictions. The success of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was marred by the escalation of the U.S. war in Vietnam. Even as the government tried desperately to offset the cost of the war, King saw the Vietnam War as a sign of a hardening contradiction between the U.S. state’s ability to fulfill its social contract to the American people, versus its need to sustain world imperialism through perpetual wars and military expansion abroad. The next stage of the Movement naturally reached for a broader, deeper coalition—a Poor People’s Campaign—to attack the “triple evils” of racism, poverty, and war. Where the Movement had earlier sought to negotiate with the state to gain equal rights, the question of war placed the Movement into more direct opposition to the state and monopoly power. America’s ignominious defeat in Vietnam spoke to the success of the Vietnamese liberation forces as much as it did to the demoralization and opposition of soldiers, young whites, and Black folk who listened to King and Muhammad Ali more than they did Lyndon B. Johnson or Richard Nixon. By 1967, when King named the U.S. government as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world,” he understood that he was marked for death. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. was the beginning of a concerted, merciless campaign to overturn the Third American Revolution as it was reaching a higher stage of development. This counter-revolution wrought more chaos and destruction than we know: it left in its wake not only the smoldering cities that erupted in anger and pain immediately after King’s death, but also the ruins of the deindustrialized, impoverished, war-like heartlands and urban metropolises that we live in today, as the nation continued to gorge itself on new wars that paved the way for the hollowing out of domestic industry as cheaper labor was secured abroad. With King’s death, the ruling class decapitated the Movement and sowed confusion in its ranks. The Black Power generation that followed, though not lacking in revolutionary zeal, largely accepted the false narrative that King had been a moderate and that nonviolence had failed. They tried to reinvent revolution by turning their backs on the revolutionary era that had produced them. Meanwhile, many of the Movement’s original freedom fighters who resumed their lives in “normal society” suffered from long standing psychological wounds akin to veterans returning home from war. Only a few—among them, Coretta Scott King, James Lawson, Diane Nash, and James Baldwin—carried the torch for peace and King’s unfinished legacy. And the nation’s white “silent majority,” having already grown cold to King at the exact moment he issued a call to break silence on America’s path of destruction, did not realize what they, too, had lost in losing King. The ruling elite again tried to reassert control over time by making King’s memory and martyrdom obsolete. In later decades, they found it safe enough to appropriate nonviolence itself: removing its revolutionary, democratic, emancipatory essence, and turning nonviolence into an empty form of protest that could be made to serve whatever agenda the state wanted. Drunk on its apparent victories, America at the close of the 20th century found itself secure as the so-called leader of the free world. Yet for the people, it was another long night of desolation and wandering. To Awaken the People We have been born into this period of counter-revolution. The political confusion and susceptibility of today’s younger and middle-aged generations are a reflection of that fact. We are scarcely aware of whence we came. It is not our fault that we have become so lost—but it is our responsibility to find our way forward. America is a contradiction: it is a globe-spanning empire that is dragging humankind to the brink of annihilation; yet it is this same nation that produced King, Baldwin, and Du Bois, and which still contains the seed of the Beloved Community. It is a society still blinded by delusions about its own freedom and apparent diversity, yet it is also an indescribably more vast, complex, and beautiful place because of the gains of the Civil Rights Movement. The Third American Revolution was forestalled and undermined—but it was not a failure. Americans are less racist than they were in 1955. They are more broadly suspicious of the ruling class than ever before. They have grown exhausted and disgusted with unending wars. These are the marks of the Third American Revolution upon the body politic of the country. Untold effort has been expended to reverse these advancements of the people’s consciousness. What is going to be our relationship to this history? What is going to be our role in this nation’s future? Such questions hang in the air all over America and are perceived, however dimly at first, by a generation that is just now having to grapple with real, inescapable political and moral questions as we face the horror of a genocide in Gaza being committed in our name, and the collapse of America’s paper-thin prestige on the world stage. The crisis of American society is a crisis of legitimacy: the people do not trust the nation’s governing institutions, making it impossible for the ruling elite to rule in their accustomed ways. A crisis is an opening. When everything is in flux, new coalitions and new ways of doing politics become possible, and the actions of ordinary people take on greater weight in deciding how the crisis will be resolved and in which direction history will move. Such a time calls for a re-examination of the Third American Revolution and a revival of nonviolence in its fullest, most creative sense. Such a time calls for a Fourth American Revolution. The broad mass of Americans are daily pushed toward anti-social impulses, toward isolation and distrust of one another. We are told that it is not our place to question the reality presented to us, but we question it anyway—making every person feel that he or she is slowly going insane as the world burns. The science of nonviolence can be developed in a multitude of new forms to help the American people find each other again; to openly confront the obscenities of our senile, inhuman elites; to create new spaces where the people can come together—unbothered by official institutions—to work out their common problems and grapple with their common future. Peace and war, poverty, violence, moral values, education: all these and more are questions that must be made democratic, that must be returned to the province of the people’s will. We are only at the tip of the iceberg of what can be conceived in this peculiar drama called the American experiment. Can it be done? Can our people find it within themselves to achieve King’s vision, or are we all doomed to go down with our war-crazed ruling elite? We do not know—the shape of the future is sharp and uncertain. But what will happen if we do nothing? What do we reveal about ourselves when we say that hundreds of millions of people in this country—and all the children to be born—are beyond saving? What does humanity demand of us, if not the complete transformation of America from an empire to a new nation that “studies war no more”? Our Common InheritanceThe Third American Revolution is the birthright of every single American, whether we came here 20 years ago or have lived here for 200 years. Diane Nash put it plainly: “My contemporaries had you in mind when we acted. We were in dangerous situations, and sometimes people would freak out. A number of times I saw the person standing next to them put their arm around that person’s shoulder and say, ‘Remember that what we’re doing is important. We’re doing this for generations yet unborn.’ So although we had not met you, you should know that we loved you.” It is worth repeating: the young formed the beating heart of the Third American Revolution. Martin Luther King was only 25 when he was called to serve as pastor of Dexter Avenue Church in Montgomery. And James Baldwin knew better than anyone that the young are uniquely capable of battling for a revolutionary vision and purpose because they feel, instinctively, that in doing so they are also fighting for their very lives. They were the children of sharecroppers, ministers, maids, doctors, and dock workers. They were prepared to pay their dues to the generations who came before them, who fought—in darkness, and against all odds—to bring them to where they stood: facing the future. We must prepare to do the same. AuthorJeremiah Kim This article was produced by Avant-Garde. Archives April 2024

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed