|

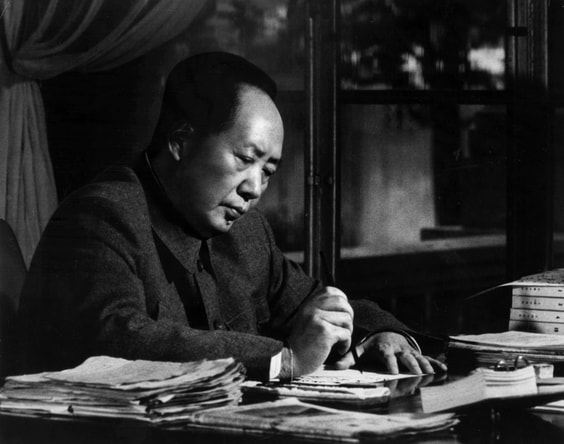

The average academic “Marxist” usually understands very well Marx’s ideas about specific topics: she can explain what is expanded reproduction, what is the difference between relative and absolute surplus, the question of the falling rate of profit, etc. And yet, despite their erudition, few of these “Marxist” academics have a proper understanding about Marxism, communism, and what they entail. By contrast, few people in history have had such a clear and distinct understanding about Marxism and its philosophy as Mao Zedong did. Before this assertion, the “Marxist” academic might giggle to herself, wondering what an “Asian despot” from a backward country of peasants, the author of simple writings addressed to the masses, could teach her about Marxism. Huey P. Newton, founder of the Black Panther Party, once said about their experience of struggle in the United States: Theory was not enough, we had said. We knew we had to act to bring about change. Without fully realizing it then, we were following Mao’s belief that if you want to know the theory and methods of revolution, you must take part in revolution. All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience.[1] Unlike the “Marxist” academic, who understands a lot about specific postulates of Marx’s work (and of some of his philosophical predecessors or successors, such as Hegel or Adorno and Horkheimer, or, perhaps, if we are dealing with a particularly daring individual, David Harvey), what Newton finds in Mao’s thought, already after initiating his revolutionary praxis with his Black Panther comrades, is a fundamental dialectical relationship between thought and action (between, say, the truth of theory and the efficacy of practice), which is precisely what the young Marx demands in his Thesis XI on Feuerbach when he claims that “[p]hilosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”[2] The “Marxist” academic, with all her erudition, forgets that the place where the truth of theory is put to test (when it claims to be revolutionary or transformative) is in the realm of concrete practice. That’s why Mao says in On Practice: The Marxist philosophy of dialectical materialism has two outstanding characteristics. One is its class nature: it openly avows that dialectical materialism is in service of the proletariat. The other is its practicality: it emphasizes the dependence of theory on practice, emphasizes that theory is based on practice and in turn serves practice. The truth of any knowledge or theory is determined not by subjective feelings, but by objective results in social practice. Only social practice can be the criterion of truth. The standpoint of practice is the primary and basic standpoint in the dialectical materialist theory of knowledge[3]. Mao’s first point here, the commitment of Marxism to the struggle of the proletariat and the oppressed classes, is not a political bias that is imposed on the theory from the outside: as anyone who has studied dialectics knows[4], the starting point from which one progresses towards every true [total] knowledge about reality is always that of the immediate experience that one has about said reality. In capitalism, that first immediate experience, necessarily partial or incomplete (and therefore in need of clarification) is always an experience of struggle, of the opposition between the individual and the whole of social reality; it is the contradiction between those who live from the system and those who are simply not allowed to live by the system. Hence, the first step towards clarifying one’s own experience (the first step towards real knowledge) is none other than the step towards praxis: the leap to rebellion, to open confrontation in the class struggle[5]. That’s why Mao says that “Marxism comprises many principles, but in the final analysis they can all be brought back to a single sentence: it is right to rebel”[6]; the event that inaugurates the transition of consciousness towards knowledge of reality as a whole (of capitalism and the immanent dynamics of its contradictions) is the class struggle that ultimately drives and mobilizes said reality. For this reason, it can be affirmed that Marxism as a materialist and dialectical theory of history is the self-awareness about the progressive clarification of one’s own consciousness in the process of class struggle, the dialectical systematization of the stages of that struggle, the rectification of errors and the progressive accumulation of political experience by which an oppressed class gradually becomes a revolutionary class (in which the proletariat acquires “class consciousness”). That is why Mao, denounced so many times by Western “Marxist” academics as an “ultra-orthodox Marxist” and “fanatic”, from his camp in Yan’an, allows himself to denounce “book worship”, and to conclude that: When we say Marxism is correct, it is certainly not because Marx was a “prophet” but because his theory has been proved correct in our practice and in our struggle. We need Marxism in our struggle. In our acceptance of his theory no such formalization of mystical notions such as that of “prophecy” ever enters our minds. Many who have read Marxist books have become renegades from the revolution, whereas illiterate workers often grasp Marxism very well. Of course we should study Marxist books, but this study must be integrated with our country’s actual conditions. We need books, but we must overcome book worship, which is divorced from the actual situation. [7] Almost as if he anticipated the criticisms of these left-wing university professors. Twenty-seven years later, in 1957, with the Chinese Communist Party already in power, Mao will assert in a speech: In order to have a real grasp of Marxism, one must learn it not only from books, but mainly through class struggle, through practical work and close contact with the masses of workers and peasants. When in addition to reading some Marxist books our intellectuals have gained some understanding through close contact with the masses of workers and peasants and through their own practical work, we will all be speaking the same language, not only the common language of patriotism and the common language of the socialist system, but probably the common language of the communist world outlook. If that happens, all of us will certainly work much better.[8] A strong contrast with the German theorist Max Horkheimer (historical leader of the first generation of the Frankfurt School, who in the 1930s one of the most lucid and fundamental texts of so-called Western Marxism, Traditional Theory and Critical Theory) and his colleague Theodor Adorno, who would not only eventually denounce the Soviet efforts to consolidate a state apparatus that would allow them to develop a modern industry capable of lifting millions out of poverty and defending themselves against the onslaught of the Nazi Wehrmacht as a “betrayal of socialism” and to the Marxian ideal of “the abolition of the State in communism”, but also, in the name of abstract universalism, would compare the struggle for independence of the Vietnamese and the colonized peoples of the world with the rise of “Hitlerian nationalism”, and likewise, they would brand as reactionary and even fascistic the student protests of the late 1960s that threatened to disrupt the normal delivery of their classes at the University of Frankfurt (and probably putting the CIA’s disapproving eye on the Institute for Social Research, with a probable cut of its government funding)[9]. Adorno would famously declare on one occasion: “When I made my theoretical model, I could not have guessed that people would try to realise it with Molotov cocktails.”[10] Against a revolutionary praxis that, in its attempt to conquer power and initiate the construction of socialism, would inevitably run into obstacles, make mistakes, and move away from pre-established abstract schemes, Horkheimer and Adorno would call for the defense of the rights of “thought” (of Pure Theory) to remain untainted, entrenching it in the faculties of philosophy and social sciences, thus preserving it from a reality and a social practice incapable of living up to “theoretical truth”. The gesture of the founding fathers of Critical Theory, by which they crowned their turn from materialism to idealism, is repeated today even by scholars of Marx’s work and researchers strongly committed to the collection, measurement and analysis of empirical data. And this is fundamentally because, as Mao understood so well, Marxism is dialectical thought, but true dialectical thought (true theoretical thought) is not (it cannot be) in opposition to social practice, to direct involvement in the history of class struggle: a perspective that claims to be dialectical and that does not merges into the real experience of class struggle, cannot aspire to a true knowledge of reality (that is: concrete, material, and multilateral, total), only to an abstract and partial view of the system, typical of a Cartesian academic subject who, consciously or unconsciously, understands herself as external to social antagonism, and therefore, as uprooted from historical reality. Certainly, Marxism is method (dialectical method), but as the Hungarian philosopher György Lukács stated: Materialist dialectic is a revolutionary dialectic. […] And this is not merely in the sense given it by Marx when he says in his first critique of Hegel that “theory becomes a material force when it grips the masses”. Even more to the point is the need to discover those features and definitions both of the theory and the ways of gripping the masses which convert the theory, the dialectical method, into a vehicle of revolution. We must extract the practical essence of theory from the method and its relation to its object [that is: to reality].[11] Hence “[i]t is not the primacy of economic motives in historical explanation that constitutes the decisive difference between Marxism and bourgeois thought, but the point of view of [social] totality.”[12] Marxism is not, then, a mere theory of social formations: it is the wisdom that is born from rebellion, from revolutions throughout history, the methodical learning of revolutionaries on how to transform reality. That is the main reason why, at the end of the day, the average “Marxist” academic and many great specialists on Marx’s work know little or nothing about Marxism, communism and what they entail. Citations [1] Newton, H.P., Revolutionary Suicide. Penguin Books: New York (2009), p. 353. [2] Marx, K., Thesis on Feuerbach. Progress Publishers: Moscow (1969). Available on marxists.org [3] Mao, Z., On Practice (2004). Available on marxists.org [4] Hegel, G.W.F, Phenomenology of Spirit. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge (2019). [5] Lukács, G., “What is Orthodox Marxism?” in History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (pp. 1-26). The MIT Press: Cambridge (1971), pp. 19-21. [6] Mao, Z., Speech marking the 60th birthday of Stalin (1939), later revised as “It is right to rebel against reactionaries.” [7] Mao, Z., Oppose Book Worship (2004). Available on marxists.org [8] Mao, Z., Speech at the Chinese Communist Party’s National Conference on Propaganda Work (2004). Available on marxists.org [9] As quoted in D. Losurdo, El Marxismo Occidental: Cómo nació, cómo murió y cómo puede resucitar. Editorial Trotta: Madrid (2018), pp. 11-12 and 78-84. [10] As quoted in M. Jay, The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute of Social Research. University of California Press: Berkeley (1973), p. 279. [11] Lukács, G., “What is Orthodox Marxism?” in History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (pp. 1-26). The MIT Press: Cambridge (1971), p. 2. [12] Lukács, G., “The Marxism of Rosa Luxemburg” in History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (pp. 27-45). The MIT Press: Cambridge (1971), p. 27. About the Author: Sebastián León is a philosophy teacher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, where he received his MA in philosophy (2018). His main subject of interest is the history of modernity, understood as a series of cultural, economic, institutional and subjective processes, in which the impetus for emancipation and rational social organization are imbricated with new and sophisticated forms of power and social control. He is a socialist militant, and has collaborated with lectures and workshops for different grassroots organizations. Originally published in Instituto Marx Engels (Dec 28, 2020)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed